An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Am J Pharm Educ

- v.74(8); 2010 Oct 11

Presenting and Evaluating Qualitative Research

The purpose of this paper is to help authors to think about ways to present qualitative research papers in the American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education . It also discusses methods for reviewers to assess the rigour, quality, and usefulness of qualitative research. Examples of different ways to present data from interviews, observations, and focus groups are included. The paper concludes with guidance for publishing qualitative research and a checklist for authors and reviewers.

INTRODUCTION

Policy and practice decisions, including those in education, increasingly are informed by findings from qualitative as well as quantitative research. Qualitative research is useful to policymakers because it often describes the settings in which policies will be implemented. Qualitative research is also useful to both pharmacy practitioners and pharmacy academics who are involved in researching educational issues in both universities and practice and in developing teaching and learning.

Qualitative research involves the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data that are not easily reduced to numbers. These data relate to the social world and the concepts and behaviors of people within it. Qualitative research can be found in all social sciences and in the applied fields that derive from them, for example, research in health services, nursing, and pharmacy. 1 It looks at X in terms of how X varies in different circumstances rather than how big is X or how many Xs are there? 2 Textbooks often subdivide research into qualitative and quantitative approaches, furthering the common assumption that there are fundamental differences between the 2 approaches. With pharmacy educators who have been trained in the natural and clinical sciences, there is often a tendency to embrace quantitative research, perhaps due to familiarity. A growing consensus is emerging that sees both qualitative and quantitative approaches as useful to answering research questions and understanding the world. Increasingly mixed methods research is being carried out where the researcher explicitly combines the quantitative and qualitative aspects of the study. 3 , 4

Like healthcare, education involves complex human interactions that can rarely be studied or explained in simple terms. Complex educational situations demand complex understanding; thus, the scope of educational research can be extended by the use of qualitative methods. Qualitative research can sometimes provide a better understanding of the nature of educational problems and thus add to insights into teaching and learning in a number of contexts. For example, at the University of Nottingham, we conducted in-depth interviews with pharmacists to determine their perceptions of continuing professional development and who had influenced their learning. We also have used a case study approach using observation of practice and in-depth interviews to explore physiotherapists' views of influences on their leaning in practice. We have conducted in-depth interviews with a variety of stakeholders in Malawi, Africa, to explore the issues surrounding pharmacy academic capacity building. A colleague has interviewed and conducted focus groups with students to explore cultural issues as part of a joint Nottingham-Malaysia pharmacy degree program. Another colleague has interviewed pharmacists and patients regarding their expectations before and after clinic appointments and then observed pharmacist-patient communication in clinics and assessed it using the Calgary Cambridge model in order to develop recommendations for communication skills training. 5 We have also performed documentary analysis on curriculum data to compare pharmacist and nurse supplementary prescribing courses in the United Kingdom.

It is important to choose the most appropriate methods for what is being investigated. Qualitative research is not appropriate to answer every research question and researchers need to think carefully about their objectives. Do they wish to study a particular phenomenon in depth (eg, students' perceptions of studying in a different culture)? Or are they more interested in making standardized comparisons and accounting for variance (eg, examining differences in examination grades after changing the way the content of a module is taught). Clearly a quantitative approach would be more appropriate in the last example. As with any research project, a clear research objective has to be identified to know which methods should be applied.

Types of qualitative data include:

- Audio recordings and transcripts from in-depth or semi-structured interviews

- Structured interview questionnaires containing substantial open comments including a substantial number of responses to open comment items.

- Audio recordings and transcripts from focus group sessions.

- Field notes (notes taken by the researcher while in the field [setting] being studied)

- Video recordings (eg, lecture delivery, class assignments, laboratory performance)

- Case study notes

- Documents (reports, meeting minutes, e-mails)

- Diaries, video diaries

- Observation notes

- Press clippings

- Photographs

RIGOUR IN QUALITATIVE RESEARCH

Qualitative research is often criticized as biased, small scale, anecdotal, and/or lacking rigor; however, when it is carried out properly it is unbiased, in depth, valid, reliable, credible and rigorous. In qualitative research, there needs to be a way of assessing the “extent to which claims are supported by convincing evidence.” 1 Although the terms reliability and validity traditionally have been associated with quantitative research, increasingly they are being seen as important concepts in qualitative research as well. Examining the data for reliability and validity assesses both the objectivity and credibility of the research. Validity relates to the honesty and genuineness of the research data, while reliability relates to the reproducibility and stability of the data.

The validity of research findings refers to the extent to which the findings are an accurate representation of the phenomena they are intended to represent. The reliability of a study refers to the reproducibility of the findings. Validity can be substantiated by a number of techniques including triangulation use of contradictory evidence, respondent validation, and constant comparison. Triangulation is using 2 or more methods to study the same phenomenon. Contradictory evidence, often known as deviant cases, must be sought out, examined, and accounted for in the analysis to ensure that researcher bias does not interfere with or alter their perception of the data and any insights offered. Respondent validation, which is allowing participants to read through the data and analyses and provide feedback on the researchers' interpretations of their responses, provides researchers with a method of checking for inconsistencies, challenges the researchers' assumptions, and provides them with an opportunity to re-analyze their data. The use of constant comparison means that one piece of data (for example, an interview) is compared with previous data and not considered on its own, enabling researchers to treat the data as a whole rather than fragmenting it. Constant comparison also enables the researcher to identify emerging/unanticipated themes within the research project.

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF QUALITATIVE RESEARCH

Qualitative researchers have been criticized for overusing interviews and focus groups at the expense of other methods such as ethnography, observation, documentary analysis, case studies, and conversational analysis. Qualitative research has numerous strengths when properly conducted.

Strengths of Qualitative Research

- Issues can be examined in detail and in depth.

- Interviews are not restricted to specific questions and can be guided/redirected by the researcher in real time.

- The research framework and direction can be quickly revised as new information emerges.

- The data based on human experience that is obtained is powerful and sometimes more compelling than quantitative data.

- Subtleties and complexities about the research subjects and/or topic are discovered that are often missed by more positivistic enquiries.

- Data usually are collected from a few cases or individuals so findings cannot be generalized to a larger population. Findings can however be transferable to another setting.

Limitations of Qualitative Research

- Research quality is heavily dependent on the individual skills of the researcher and more easily influenced by the researcher's personal biases and idiosyncrasies.

- Rigor is more difficult to maintain, assess, and demonstrate.

- The volume of data makes analysis and interpretation time consuming.

- It is sometimes not as well understood and accepted as quantitative research within the scientific community

- The researcher's presence during data gathering, which is often unavoidable in qualitative research, can affect the subjects' responses.

- Issues of anonymity and confidentiality can present problems when presenting findings

- Findings can be more difficult and time consuming to characterize in a visual way.

PRESENTATION OF QUALITATIVE RESEARCH FINDINGS

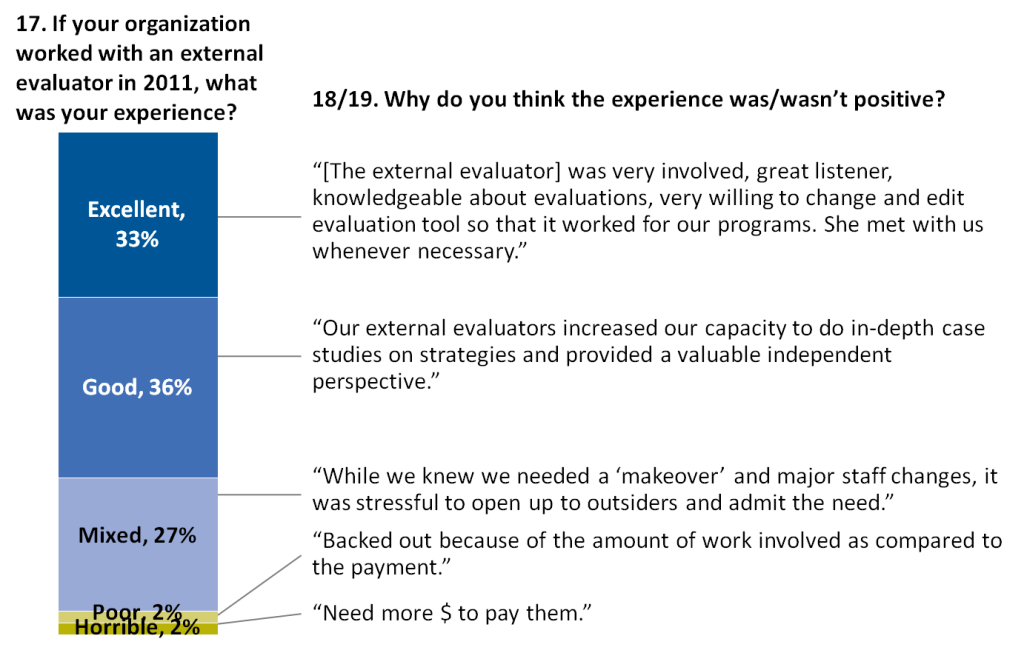

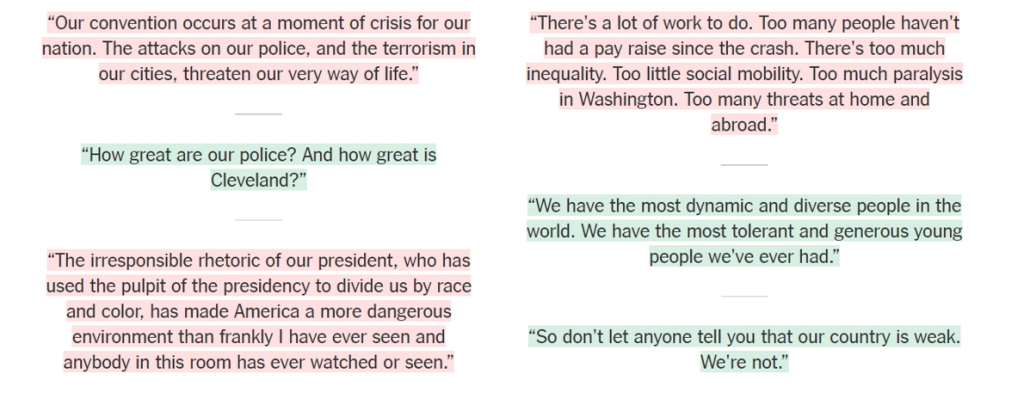

The following extracts are examples of how qualitative data might be presented:

Data From an Interview.

The following is an example of how to present and discuss a quote from an interview.

The researcher should select quotes that are poignant and/or most representative of the research findings. Including large portions of an interview in a research paper is not necessary and often tedious for the reader. The setting and speakers should be established in the text at the end of the quote.

The student describes how he had used deep learning in a dispensing module. He was able to draw on learning from a previous module, “I found that while using the e learning programme I was able to apply the knowledge and skills that I had gained in last year's diseases and goals of treatment module.” (interviewee 22, male)

This is an excerpt from an article on curriculum reform that used interviews 5 :

The first question was, “Without the accreditation mandate, how much of this curriculum reform would have been attempted?” According to respondents, accreditation played a significant role in prompting the broad-based curricular change, and their comments revealed a nuanced view. Most indicated that the change would likely have occurred even without the mandate from the accreditation process: “It reflects where the profession wants to be … training a professional who wants to take on more responsibility.” However, they also commented that “if it were not mandated, it could have been a very difficult road.” Or it “would have happened, but much later.” The change would more likely have been incremental, “evolutionary,” or far more limited in its scope. “Accreditation tipped the balance” was the way one person phrased it. “Nobody got serious until the accrediting body said it would no longer accredit programs that did not change.”

Data From Observations

The following example is some data taken from observation of pharmacist patient consultations using the Calgary Cambridge guide. 6 , 7 The data are first presented and a discussion follows:

Pharmacist: We will soon be starting a stop smoking clinic. Patient: Is the interview over now? Pharmacist: No this is part of it. (Laughs) You can't tell me to bog off (sic) yet. (pause) We will be starting a stop smoking service here, Patient: Yes. Pharmacist: with one-to-one and we will be able to help you or try to help you. If you want it. In this example, the pharmacist has picked up from the patient's reaction to the stop smoking clinic that she is not receptive to advice about giving up smoking at this time; in fact she would rather end the consultation. The pharmacist draws on his prior relationship with the patient and makes use of a joke to lighten the tone. He feels his message is important enough to persevere but he presents the information in a succinct and non-pressurised way. His final comment of “If you want it” is important as this makes it clear that he is not putting any pressure on the patient to take up this offer. This extract shows that some patient cues were picked up, and appropriately dealt with, but this was not the case in all examples.

Data From Focus Groups

This excerpt from a study involving 11 focus groups illustrates how findings are presented using representative quotes from focus group participants. 8

Those pharmacists who were initially familiar with CPD endorsed the model for their peers, and suggested it had made a meaningful difference in the way they viewed their own practice. In virtually all focus groups sessions, pharmacists familiar with and supportive of the CPD paradigm had worked in collaborative practice environments such as hospital pharmacy practice. For these pharmacists, the major advantage of CPD was the linking of workplace learning with continuous education. One pharmacist stated, “It's amazing how much I have to learn every day, when I work as a pharmacist. With [the learning portfolio] it helps to show how much learning we all do, every day. It's kind of satisfying to look it over and see how much you accomplish.” Within many of the learning portfolio-sharing sessions, debates emerged regarding the true value of traditional continuing education and its outcome in changing an individual's practice. While participants appreciated the opportunity for social and professional networking inherent in some forms of traditional CE, most eventually conceded that the academic value of most CE programming was limited by the lack of a systematic process for following-up and implementing new learning in the workplace. “Well it's nice to go to these [continuing education] events, but really, I don't know how useful they are. You go, you sit, you listen, but then, well I at least forget.”

The following is an extract from a focus group (conducted by the author) with first-year pharmacy students about community placements. It illustrates how focus groups provide a chance for participants to discuss issues on which they might disagree.

Interviewer: So you are saying that you would prefer health related placements? Student 1: Not exactly so long as I could be developing my communication skill. Student 2: Yes but I still think the more health related the placement is the more I'll gain from it. Student 3: I disagree because other people related skills are useful and you may learn those from taking part in a community project like building a garden. Interviewer: So would you prefer a mixture of health and non health related community placements?

GUIDANCE FOR PUBLISHING QUALITATIVE RESEARCH

Qualitative research is becoming increasingly accepted and published in pharmacy and medical journals. Some journals and publishers have guidelines for presenting qualitative research, for example, the British Medical Journal 9 and Biomedcentral . 10 Medical Education published a useful series of articles on qualitative research. 11 Some of the important issues that should be considered by authors, reviewers and editors when publishing qualitative research are discussed below.

Introduction.

A good introduction provides a brief overview of the manuscript, including the research question and a statement justifying the research question and the reasons for using qualitative research methods. This section also should provide background information, including relevant literature from pharmacy, medicine, and other health professions, as well as literature from the field of education that addresses similar issues. Any specific educational or research terminology used in the manuscript should be defined in the introduction.

The methods section should clearly state and justify why the particular method, for example, face to face semistructured interviews, was chosen. The method should be outlined and illustrated with examples such as the interview questions, focusing exercises, observation criteria, etc. The criteria for selecting the study participants should then be explained and justified. The way in which the participants were recruited and by whom also must be stated. A brief explanation/description should be included of those who were invited to participate but chose not to. It is important to consider “fair dealing,” ie, whether the research design explicitly incorporates a wide range of different perspectives so that the viewpoint of 1 group is never presented as if it represents the sole truth about any situation. The process by which ethical and or research/institutional governance approval was obtained should be described and cited.

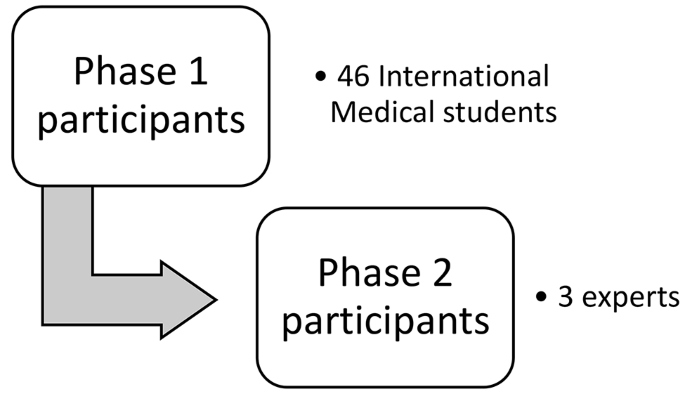

The study sample and the research setting should be described. Sampling differs between qualitative and quantitative studies. In quantitative survey studies, it is important to select probability samples so that statistics can be used to provide generalizations to the population from which the sample was drawn. Qualitative research necessitates having a small sample because of the detailed and intensive work required for the study. So sample sizes are not calculated using mathematical rules and probability statistics are not applied. Instead qualitative researchers should describe their sample in terms of characteristics and relevance to the wider population. Purposive sampling is common in qualitative research. Particular individuals are chosen with characteristics relevant to the study who are thought will be most informative. Purposive sampling also may be used to produce maximum variation within a sample. Participants being chosen based for example, on year of study, gender, place of work, etc. Representative samples also may be used, for example, 20 students from each of 6 schools of pharmacy. Convenience samples involve the researcher choosing those who are either most accessible or most willing to take part. This may be fine for exploratory studies; however, this form of sampling may be biased and unrepresentative of the population in question. Theoretical sampling uses insights gained from previous research to inform sample selection for a new study. The method for gaining informed consent from the participants should be described, as well as how anonymity and confidentiality of subjects were guaranteed. The method of recording, eg, audio or video recording, should be noted, along with procedures used for transcribing the data.

Data Analysis.

A description of how the data were analyzed also should be included. Was computer-aided qualitative data analysis software such as NVivo (QSR International, Cambridge, MA) used? Arrival at “data saturation” or the end of data collection should then be described and justified. A good rule when considering how much information to include is that readers should have been given enough information to be able to carry out similar research themselves.

One of the strengths of qualitative research is the recognition that data must always be understood in relation to the context of their production. 1 The analytical approach taken should be described in detail and theoretically justified in light of the research question. If the analysis was repeated by more than 1 researcher to ensure reliability or trustworthiness, this should be stated and methods of resolving any disagreements clearly described. Some researchers ask participants to check the data. If this was done, it should be fully discussed in the paper.

An adequate account of how the findings were produced should be included A description of how the themes and concepts were derived from the data also should be included. Was an inductive or deductive process used? The analysis should not be limited to just those issues that the researcher thinks are important, anticipated themes, but also consider issues that participants raised, ie, emergent themes. Qualitative researchers must be open regarding the data analysis and provide evidence of their thinking, for example, were alternative explanations for the data considered and dismissed, and if so, why were they dismissed? It also is important to present outlying or negative/deviant cases that did not fit with the central interpretation.

The interpretation should usually be grounded in interviewees or respondents' contributions and may be semi-quantified, if this is possible or appropriate, for example, “Half of the respondents said …” “The majority said …” “Three said…” Readers should be presented with data that enable them to “see what the researcher is talking about.” 1 Sufficient data should be presented to allow the reader to clearly see the relationship between the data and the interpretation of the data. Qualitative data conventionally are presented by using illustrative quotes. Quotes are “raw data” and should be compiled and analyzed, not just listed. There should be an explanation of how the quotes were chosen and how they are labeled. For example, have pseudonyms been given to each respondent or are the respondents identified using codes, and if so, how? It is important for the reader to be able to see that a range of participants have contributed to the data and that not all the quotes are drawn from 1 or 2 individuals. There is a tendency for authors to overuse quotes and for papers to be dominated by a series of long quotes with little analysis or discussion. This should be avoided.

Participants do not always state the truth and may say what they think the interviewer wishes to hear. A good qualitative researcher should not only examine what people say but also consider how they structured their responses and how they talked about the subject being discussed, for example, the person's emotions, tone, nonverbal communication, etc. If the research was triangulated with other qualitative or quantitative data, this should be discussed.

Discussion.

The findings should be presented in the context of any similar previous research and or theories. A discussion of the existing literature and how this present research contributes to the area should be included. A consideration must also be made about how transferrable the research would be to other settings. Any particular strengths and limitations of the research also should be discussed. It is common practice to include some discussion within the results section of qualitative research and follow with a concluding discussion.

The author also should reflect on their own influence on the data, including a consideration of how the researcher(s) may have introduced bias to the results. The researcher should critically examine their own influence on the design and development of the research, as well as on data collection and interpretation of the data, eg, were they an experienced teacher who researched teaching methods? If so, they should discuss how this might have influenced their interpretation of the results.

Conclusion.

The conclusion should summarize the main findings from the study and emphasize what the study adds to knowledge in the area being studied. Mays and Pope suggest the researcher ask the following 3 questions to determine whether the conclusions of a qualitative study are valid 12 : How well does this analysis explain why people behave in the way they do? How comprehensible would this explanation be to a thoughtful participant in the setting? How well does the explanation cohere with what we already know?

CHECKLIST FOR QUALITATIVE PAPERS

This paper establishes criteria for judging the quality of qualitative research. It provides guidance for authors and reviewers to prepare and review qualitative research papers for the American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education . A checklist is provided in Appendix 1 to assist both authors and reviewers of qualitative data.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thank you to the 3 reviewers whose ideas helped me to shape this paper.

Appendix 1. Checklist for authors and reviewers of qualitative research.

Introduction

- □ Research question is clearly stated.

- □ Research question is justified and related to the existing knowledge base (empirical research, theory, policy).

- □ Any specific research or educational terminology used later in manuscript is defined.

- □ The process by which ethical and or research/institutional governance approval was obtained is described and cited.

- □ Reason for choosing particular research method is stated.

- □ Criteria for selecting study participants are explained and justified.

- □ Recruitment methods are explicitly stated.

- □ Details of who chose not to participate and why are given.

- □ Study sample and research setting used are described.

- □ Method for gaining informed consent from the participants is described.

- □ Maintenance/Preservation of subject anonymity and confidentiality is described.

- □ Method of recording data (eg, audio or video recording) and procedures for transcribing data are described.

- □ Methods are outlined and examples given (eg, interview guide).

- □ Decision to stop data collection is described and justified.

- □ Data analysis and verification are described, including by whom they were performed.

- □ Methods for identifying/extrapolating themes and concepts from the data are discussed.

- □ Sufficient data are presented to allow a reader to assess whether or not the interpretation is supported by the data.

- □ Outlying or negative/deviant cases that do not fit with the central interpretation are presented.

- □ Transferability of research findings to other settings is discussed.

- □ Findings are presented in the context of any similar previous research and social theories.

- □ Discussion often is incorporated into the results in qualitative papers.

- □ A discussion of the existing literature and how this present research contributes to the area is included.

- □ Any particular strengths and limitations of the research are discussed.

- □ Reflection of the influence of the researcher(s) on the data, including a consideration of how the researcher(s) may have introduced bias to the results is included.

Conclusions

- □ The conclusion states the main finings of the study and emphasizes what the study adds to knowledge in the subject area.

- AI Templates

- Get a demo Sign up for free Log in Log in

Buttoning up research: How to present and visualize qualitative data

15 Minute Read

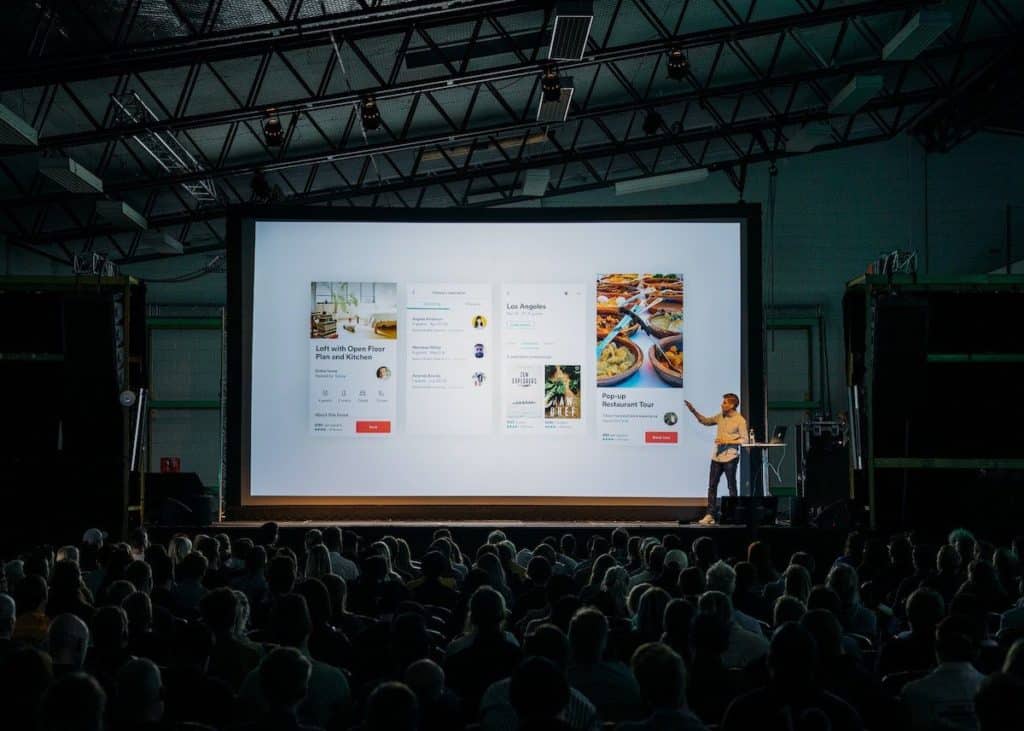

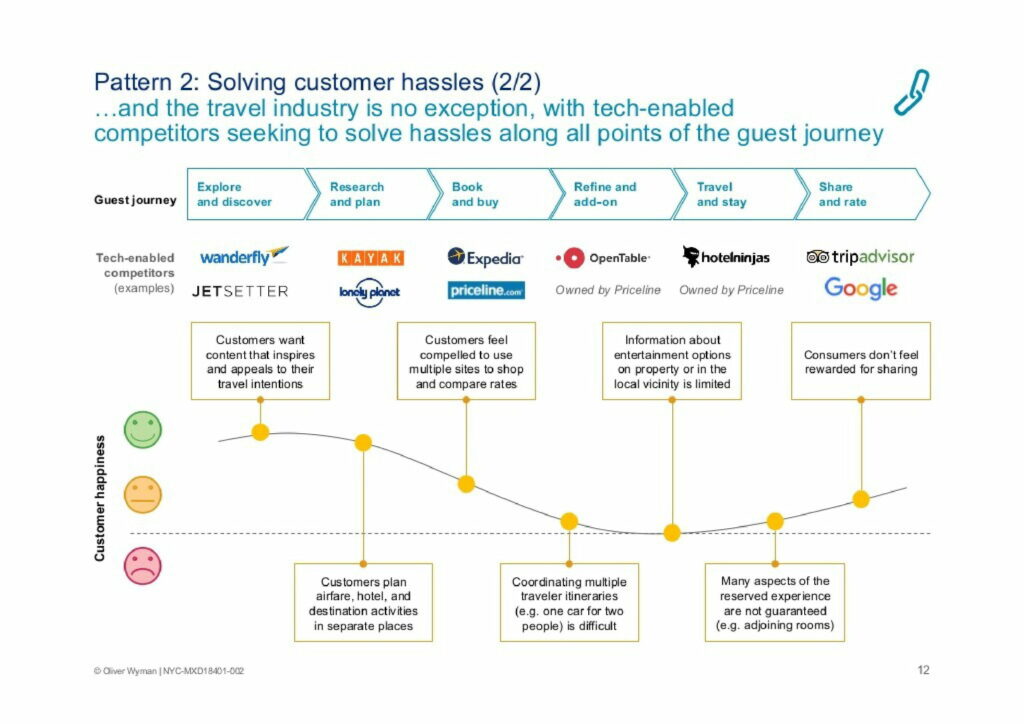

There is no doubt that data visualization is an important part of the qualitative research process. Whether you're preparing a presentation or writing up a report, effective visualizations can help make your findings clear and understandable for your audience.

In this blog post, we'll discuss some tips for creating effective visualizations of qualitative data.

First, let's take a closer look at what exactly qualitative data is.

What is qualitative data?

Qualitative data is information gathered through observation, questionnaires, and interviews. It's often subjective, meaning that the researcher has to interpret it to draw meaningful conclusions from it.

The difference between qualitative data and quantitative data

When researchers use the terms qualitative and quantitative, they're referring to two different types of data. Qualitative data is subjective and descriptive, while quantitative data is objective and numerical.

Qualitative data is often used in research involving psychology or sociology. This is usually where a researcher may be trying to identify patterns or concepts related to people's behavior or attitudes. It may also be used in research involving economics or finance, where the focus is on numerical values such as price points or profit margins.

Before we delve into how best to present and visualize qualitative data, it's important that we highlight how to be gathering this data in the first place.

How best to gather qualitative data

In order to create an effective visualization of qualitative data, ensure that the right kind of information has been gathered.

Here are six ways to gather the most accurate qualitative data:

- Define your research question: What data is being set out to collect? A qualitative research question is a definite or clear statement about a condition to be improved, a project’s area of concern, a troubling question that exists, or a difficulty to be eliminated. It not only defines who the participants will be but guides the data collection methods needed to achieve the most detailed responses.

- Determine the best data collection method(s): The data collected should be appropriate to answer the research question. Some common qualitative data collection methods include interviews, focus groups, observations, or document analysis. Consider the strengths and weaknesses of each option before deciding which one is best suited to answer the research question.

- Develop a cohesive interview guide: Creating an interview guide allows researchers to ask more specific questions and encourages thoughtful responses from participants. It’s important to design questions in such a way that they are centered around the topic of discussion and elicit meaningful insight into the issue at hand. Avoid leading or biased questions that could influence participants’ answers, and be aware of cultural nuances that may affect their answers.

- Stay neutral – let participants share their stories: The goal is to obtain useful information, not to influence the participant’s answer. Allowing participants to express themselves freely will help to gather more honest and detailed responses. It’s important to maintain a neutral tone throughout interviews and avoid judgment or opinions while they are sharing their story.

- Work with at least one additional team member when conducting qualitative research: Participants should always feel comfortable while providing feedback on a topic, so it can be helpful to have an extra team member present during the interview process – particularly if this person is familiar with the topic being discussed. This will ensure that the atmosphere of the interview remains respectful and encourages participants to speak openly and honestly.

- Analyze your findings: Once all of the data has been collected, it’s important to analyze it in order to draw meaningful conclusions. Use tools such as qualitative coding or content analysis to identify patterns or themes in the data, then compare them with prior research or other data sources. This will help to draw more accurate and useful insights from the results.

By following these steps, you will be well-prepared to collect and analyze qualitative data for your research project. Next, let's focus on how best to present the qualitative data that you have gathered and analyzed.

Create your own AI-powered templates for better, faster research synthesis. Discover new customer insights from data instantly.

The top 10 things Notably shipped in 2023 and themes for 2024.

How to visually present qualitative data.

When it comes to how to present qualitative data visually, the goal is to make research findings clear and easy to understand. To do this, use visuals that are both attractive and informative.

Presenting qualitative data visually helps to bring the user’s attention to specific items and draw them into a more in-depth analysis. Visuals provide an efficient way to communicate complex information, making it easier for the audience to comprehend.

Additionally, visuals can help engage an audience by making a presentation more interesting and interactive.

Here are some tips for creating effective visuals from qualitative data:

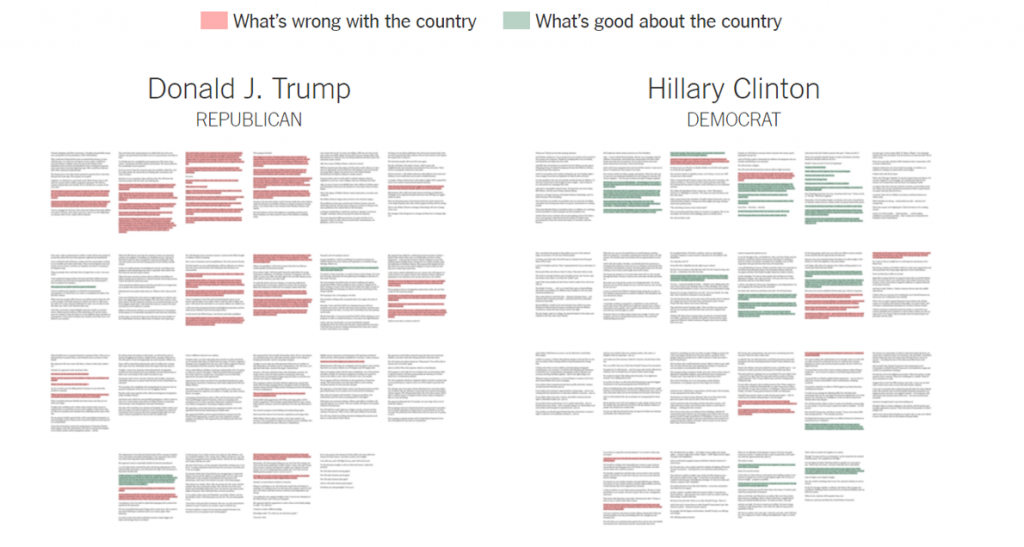

- Choose the right type of visualization: Consider which type of visual would best convey the story that is being told through the research. For example, bar charts or line graphs might be appropriate for tracking changes over time, while pie charts or word clouds could help show patterns in categorical data.

- Include contextual information: In addition to showing the actual numbers, it's helpful to include any relevant contextual information in order to provide context for the audience. This can include details such as the sample size, any anomalies that occurred during data collection, or other environmental factors.

- Make it easy to understand: Always keep visuals simple and avoid adding too much detail or complexity. This will help ensure that viewers can quickly grasp the main points without getting overwhelmed by all of the information.

- Use color strategically: Color can be used to draw attention to certain elements in your visual and make it easier for viewers to find the most important parts of it. Just be sure not to use too many different colors, as this could create confusion instead of clarity.

- Use charts or whiteboards: Using charts or whiteboards can help to explain the data in more detail and get viewers engaged in a discussion. This type of visual tool can also be used to create storyboards that illustrate the data over time, helping to bring your research to life.

Visualizing qualitative data in Notably

Notably helps researchers visualize their data on a flexible canvas, charts, and evidence based insights. As an all-in-one research platform, Notably enables researchers to collect, analyze and present qualitative data effectively.

Notably provides an intuitive interface for analyzing data from a variety of sources, including interviews, surveys, desk research, and more. Its powerful analytics engine then helps you to quickly identify insights and trends in your data . Finally, the platform makes it easy to create beautiful visuals that will help to communicate research findings with confidence.

Research Frameworks in Analysis

The canvas in Analysis is a multi-dimensional workspace to play with your data spatially to find likeness and tension. Here, you may use a grounded theory approach to drag and drop notes into themes or patterns that emerge in your research. Utilizing the canvas tools such as shapes, lines, and images, allows researchers to build out frameworks such as journey maps, empathy maps, 2x2's, etc. to help synthesize their data.

Going one step further, you may begin to apply various lenses to this data driven canvas. For example, recoloring by sentiment shows where pain points may distributed across your customer journey. Or, recoloring by participant may reveal if one of your participants may be creating a bias towards a particular theme.

Exploring Qualitative Data through a Quantitative Lens

Once you have begun your analysis, you may visualize your qualitative data in a quantitative way through charts. You may choose between a pie chart and or a stacked bar chart to visualize your data. From here, you can segment your data to break down the ‘bar’ in your bar chart and slices in your pie chart one step further.

To segment your data, you can choose between ‘Tag group’, ‘Tag’, ‘Theme’, and ‘Participant'. Each group shows up as its own bar in the bar chart or slice in the pie chart. For example, try grouping data as ‘Participant’ to see the volume of notes assigned to each person. Or, group by ‘Tag group’ to see which of your tag groups have the most notes.

Depending on how you’ve grouped or segmented your charts will affect the options available to color your chart. Charts use colors that are a mix of sentiment, tag, theme, and default colors. Consider color as a way of assigning another layer of meaning to your data. For example, choose a red color for tags or themes that are areas of friction or pain points. Use blue for tags that represent opportunities.

AI Powered Insights and Cover Images

One of the most powerful features in Analysis is the ability to generate insights with AI. Insights combine information, inspiration, and intuition to help bridge the gap between knowledge and wisdom. Even before you have any tags or themes, you may generate an AI Insight from your entire data set. You'll be able to choose one of our AI Insight templates that are inspired by trusted design thinking frameworks to stimulate generative, and divergent thinking. With just the click of a button, you'll get an insight that captures the essence and story of your research. You may experiment with a combination of tags, themes, and different templates or, create your own custom AI template. These insights are all evidence-based, and are centered on the needs of real people. You may package these insights up to present your research by embedding videos, quotes and using AI to generate unique cover image.

You can sign up to run an end to end research project for free and receive tips on how to make the most out of your data. Want to chat about how Notably can help your team do better, faster research? Book some time here for a 1:1 demo with your whole team.

Meet Posty: Your AI Research Assistant for Automatic Analysis

Introducing Notably + Miro Integration: 3 Tips to Analyze Miro Boards with AI in Notably

Give your research synthesis superpowers..

Try Teams for 7 days

Free for 1 project

- UNC Libraries

- HSL Subject Research

- Qualitative Research Resources

- Presenting Qualitative Research

Qualitative Research Resources: Presenting Qualitative Research

Created by health science librarians.

- What is Qualitative Research?

- Qualitative Research Basics

- Special Topics

- Training Opportunities: UNC & Beyond

- Help at UNC

- Qualitative Software for Coding/Analysis

- Software for Audio, Video, Online Surveys

- Finding Qualitative Studies

- Assessing Qualitative Research

- Writing Up Your Research

- Integrating Qualitative Research into Systematic Reviews

- Publishing Qualitative Research

Presenting Qualitative Research, with a focus on posters

- Qualitative & Libraries: a few gems

- Data Repositories

Example posters

- The Meaning of Work for People with MS: a Qualitative Study A good example with quotes

- Fostering Empathy through Design Thinking Among Fourth Graders in Trinidad and Tobago Includes quotes, photos, diagrams, and other artifacts from qualitative study

- Examining the Use and Perception of Harm of JUULs by College Students: A Qualitative Study Another interesting example to consider

- NLM Informationist Supplement Grant: Daring to Dive into Documentation to Determine Impact An example from the Carolina Digital Repository discussed in a class more... less... Allegri, F., Hayes, B., & Renner, B. (2017). NLM Informationist Supplement Grant: Daring to Dive into Documentation to Determine Impact. https://doi.org/10.17615/bk34-p037

- Qualitative Posters in F1000 Research Archive (filtered on "qualitative" in title) Sample qualitative posters

- Qualitative Posters in F1000 Research Archive (filtered on "qualitative" in keywords) Sample qualitative posters

Michelle A. Krieger Blog (example, posts follow an APA convention poster experience with qualitative posters):

- Qualitative Data and Research Posters I

- Qualitative Data and Research Posters II

"Oldies but goodies":

- How to Visualize Qualitative Data: Ann K. Emery, September 25, 2014 Data Visualization / Chart Choosing, Color-Coding by Category, Diagrams, Icons, Photographs, Qualitative, Text, Timelines, Word Clouds more... less... Getting a little older, and a commercial site, but with some good ideas to get you think.

- Russell, C. K., Gregory, D. M., & Gates, M. F. (1996). Aesthetics and Substance in Qualitative Research Posters. Qualitative Health Research, 6(4), 542–552. Older article with much good information. Poster materials section less applicable.Link is for UNC-Chapel Hill affiliated users.

Additional resources

- CDC Coffee Break: Considerations for Presenting Qualitative Data (Mark D. Rivera, March 13, 2018) PDF download of slide presentation. Display formats section begins on slide 10.

- Print Book (Davis Library): Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldaña, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook, 3rd edition From Paul Mihas, Assistant Director of Education and Qualitative Research at the Odum Institute for Research in Social Science at UNC: Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook (4th ed.) by Miles, Huberman, and Saldana has a section on Displaying the Data (and a chapter on Designing Matrix, Network, and Graphic Displays) that can help students consider numerous options for visually synthesizing data and findings. Many of the suggestions can be applied to designing posters (April 15, 2021).

- << Previous: Publishing Qualitative Research

- Next: Qualitative & Libraries: a few gems >>

- Last Updated: Jul 28, 2024 4:11 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.unc.edu/qual

blog @ precision

Presenting your qualitative analysis findings: tables to include in chapter 4.

The earliest stages of developing a doctoral dissertation—most specifically the topic development and literature review stages—require that you immerse yourself in a ton of existing research related to your potential topic. If you have begun writing your dissertation proposal, you have undoubtedly reviewed countless results and findings sections of studies in order to help gain an understanding of what is currently known about your topic.

In this process, we’re guessing that you observed a distinct pattern: Results sections are full of tables. Indeed, the results chapter for your own dissertation will need to be similarly packed with tables. So, if you’re preparing to write up the results of your statistical analysis or qualitative analysis, it will probably help to review your APA editing manual to brush up on your table formatting skills. But, aside from formatting, how should you develop the tables in your results chapter?

In quantitative studies, tables are a handy way of presenting the variety of statistical analysis results in a form that readers can easily process. You’ve probably noticed that quantitative studies present descriptive results like mean, mode, range, standard deviation, etc., as well the inferential results that indicate whether significant relationships or differences were found through the statistical analysis . These are pretty standard tables that you probably learned about in your pre-dissertation statistics courses.

But, what if you are conducting qualitative analysis? What tables are appropriate for this type of study? This is a question we hear often from our dissertation assistance clients, and with good reason. University guidelines for results chapters often contain vague instructions that guide you to include “appropriate tables” without specifying what exactly those are. To help clarify on this point, we asked our qualitative analysis experts to share their recommendations for tables to include in your Chapter 4.

Demographics Tables

As with studies using quantitative methods , presenting an overview of your sample demographics is useful in studies that use qualitative research methods. The standard demographics table in a quantitative study provides aggregate information for what are often large samples. In other words, such tables present totals and percentages for demographic categories within the sample that are relevant to the study (e.g., age, gender, job title).

If conducting qualitative research for your dissertation, however, you will use a smaller sample and obtain richer data from each participant than in quantitative studies. To enhance thick description—a dimension of trustworthiness—it will help to present sample demographics in a table that includes information on each participant. Remember that ethical standards of research require that all participant information be deidentified, so use participant identification numbers or pseudonyms for each participant, and do not present any personal information that would allow others to identify the participant (Blignault & Ritchie, 2009). Table 1 provides participant demographics for a hypothetical qualitative research study exploring the perspectives of persons who were formerly homeless regarding their experiences of transitioning into stable housing and obtaining employment.

Participant Demographics

| Participant ID | Gender | Age | Current Living Situation |

| P1 | Female | 34 | Alone |

| P2 | Male | 27 | With Family |

| P3 | Male | 44 | Alone |

| P4 | Female | 46 | With Roommates |

| P5 | Female | 25 | With Family |

| P6 | Male | 30 | With Roommates |

| P7 | Male | 38 | With Roommates |

| P8 | Male | 51 | Alone |

Tables to Illustrate Initial Codes

Most of our dissertation consulting clients who are conducting qualitative research choose a form of thematic analysis . Qualitative analysis to identify themes in the data typically involves a progression from (a) identifying surface-level codes to (b) developing themes by combining codes based on shared similarities. As this process is inherently subjective, it is important that readers be able to evaluate the correspondence between the data and your findings (Anfara et al., 2002). This supports confirmability, another dimension of trustworthiness .

A great way to illustrate the trustworthiness of your qualitative analysis is to create a table that displays quotes from the data that exemplify each of your initial codes. Providing a sample quote for each of your codes can help the reader to assess whether your coding was faithful to the meanings in the data, and it can also help to create clarity about each code’s meaning and bring the voices of your participants into your work (Blignault & Ritchie, 2009).

Table 2 is an example of how you might present information regarding initial codes. Depending on your preference or your dissertation committee’s preference, you might also present percentages of the sample that expressed each code. Another common piece of information to include is which actual participants expressed each code. Note that if your qualitative analysis yields a high volume of codes, it may be appropriate to present the table as an appendix.

Initial Codes

| Initial code | of participants contributing ( =8) | of transcript excerpts assigned | Sample quote |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daily routine of going to work enhanced sense of identity | 7 | 12 | “It’s just that good feeling of getting up every day like everyone else and going to work, of having that pattern that’s responsible. It makes you feel good about yourself again.” (P3) |

| Experienced discrimination due to previous homelessness | 2 | 3 | “At my last job, I told a couple other people on my shift I used to be homeless, and then, just like that, I get put into a worse job with less pay. The boss made some excuse why they did that, but they didn’t want me handling the money is why. They put me in a lower level job two days after I talk to people about being homeless in my past. That’s no coincidence if you ask me.” (P6) |

| Friends offered shared housing | 3 | 3 | “My friend from way back had a spare room after her kid moved out. She let me stay there until I got back on my feet.” (P4) |

| Mental health services essential in getting into housing | 5 | 7 | “Getting my addiction treated was key. That was a must. My family wasn’t gonna let me stay around their place without it. So that was a big help for getting back into a place.” (P2) |

Tables to Present the Groups of Codes That Form Each Theme

As noted previously, most of our dissertation assistance clients use a thematic analysis approach, which involves multiple phases of qualitative analysis that eventually result in themes that answer the dissertation’s research questions. After initial coding is completed, the analysis process involves (a) examining what different codes have in common and then (b) grouping similar codes together in ways that are meaningful given your research questions. In other words, the common threads that you identify across multiple codes become the theme that holds them all together—and that theme answers one of your research questions.

As with initial coding, grouping codes together into themes involves your own subjective interpretations, even when aided by qualitative analysis software such as NVivo or MAXQDA. In fact, our dissertation assistance clients are often surprised to learn that qualitative analysis software does not complete the analysis in the same ways that statistical analysis software such as SPSS does. While statistical analysis software completes the computations for you, qualitative analysis software does not have such analysis capabilities. Software such as NVivo provides a set of organizational tools that make the qualitative analysis far more convenient, but the analysis itself is still a very human process (Burnard et al., 2008).

Because of the subjective nature of qualitative analysis, it is important to show the underlying logic behind your thematic analysis in tables—such tables help readers to assess the trustworthiness of your analysis. Table 3 provides an example of how to present the codes that were grouped together to create themes, and you can modify the specifics of the table based on your preferences or your dissertation committee’s requirements. For example, this type of table might be presented to illustrate the codes associated with themes that answer each research question.

Grouping of Initial Codes to Form Themes

| Theme Initial codes grouped to form theme | of participants contributing ( =8) | of transcript excerpts assigned |

| Assistance from friends, family, or strangers was instrumental in getting back into stable housing | 6 | 10 |

| Family member assisted them to get into housing | ||

| Friends offered shared housing | ||

| Stranger offered shared housing | ||

| Obtaining professional support was essential for overcoming the cascading effects of poverty and homelessness | 7 | 19 |

| Financial benefits made obtaining housing possible | ||

| Mental health services essential in getting into housing | ||

| Social services helped navigate housing process | ||

| Stigma and concerns about discrimination caused them to feel uncomfortable socializing with coworkers | 6 | 9 |

| Experienced discrimination due to previous homelessness | ||

| Feared negative judgment if others learned of their pasts | ||

| Routine productivity and sense of making a contribution helped to restore self-concept and positive social identity | 8 | 21 |

| Daily routine of going to work enhanced sense of identity | ||

| Feels good to contribute to society/organization | ||

| Seeing products of their efforts was rewarding |

Tables to Illustrate the Themes That Answer Each Research Question

Creating alignment throughout your dissertation is an important objective, and to maintain alignment in your results chapter, the themes you present must clearly answer your research questions. Conducting qualitative analysis is an in-depth process of immersion in the data, and many of our dissertation consulting clients have shared that it’s easy to lose your direction during the process. So, it is important to stay focused on your research questions during the qualitative analysis and also to show the reader exactly which themes—and subthemes, as applicable—answered each of the research questions.

Below, Table 4 provides an example of how to display the thematic findings of your study in table form. Depending on your dissertation committee’s preference or your own, you might present all research questions and all themes and subthemes in a single table. Or, you might provide separate tables to introduce the themes for each research question as you progress through your presentation of the findings in the chapter.

Emergent Themes and Research Questions

| Research question

| Themes that address question

|

| RQ1. How do adults who have previously experienced homelessness describe their transitions to stable housing?

| Theme 1: Assistance from friends, family, or strangers was instrumental in getting back into stable housing Theme 2: Obtaining professional support was essential for overcoming the cascading effects of poverty and homelessness

|

| RQ2. How do adults who have previously experienced homelessness describe returning to paid employment?

| Theme 3: Self-perceived stigma caused them to feel uncomfortable socializing with coworkers Theme 4: Routine productivity and sense of making a contribution helped to restore self-concept and positive social identity |

Bonus Tip! Figures to Spice Up Your Results

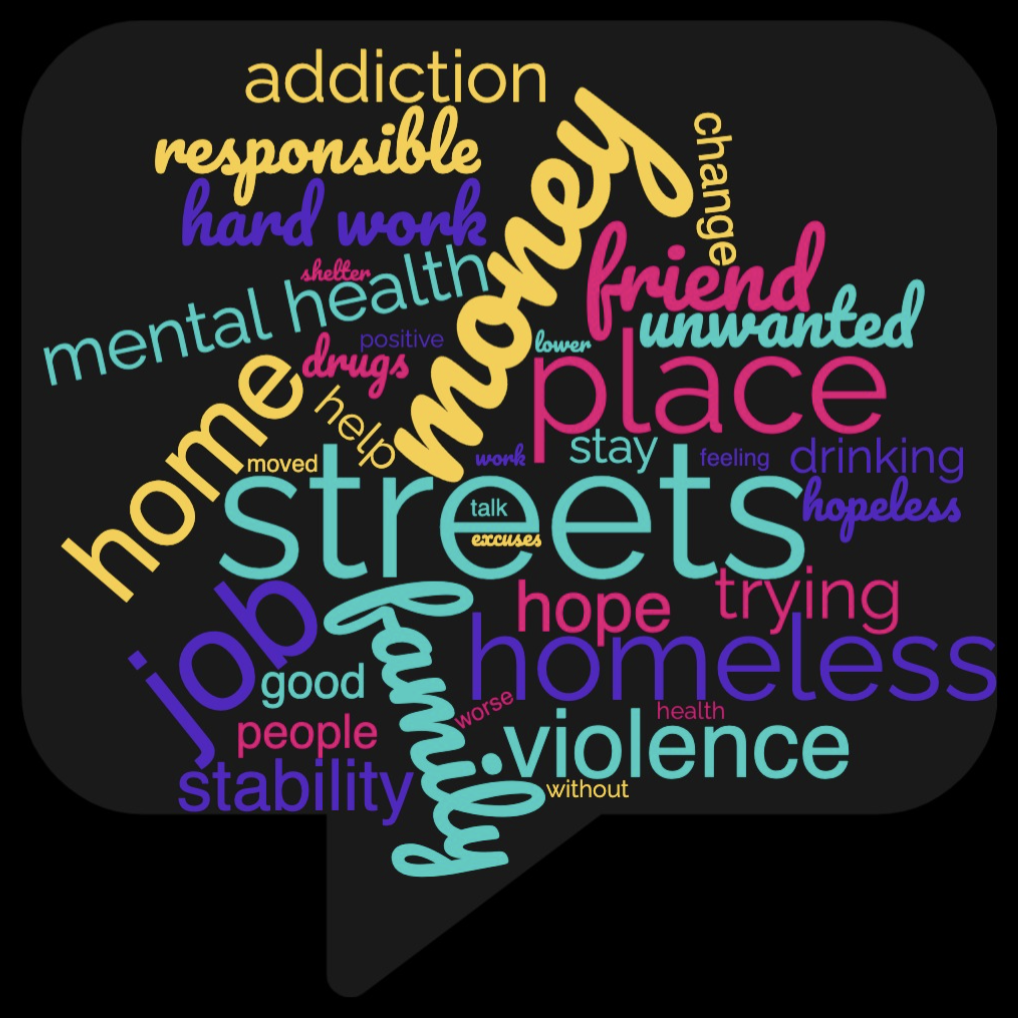

Although dissertation committees most often wish to see tables such as the above in qualitative results chapters, some also like to see figures that illustrate the data. Qualitative software packages such as NVivo offer many options for visualizing your data, such as mind maps, concept maps, charts, and cluster diagrams. A common choice for this type of figure among our dissertation assistance clients is a tree diagram, which shows the connections between specified words and the words or phrases that participants shared most often in the same context. Another common choice of figure is the word cloud, as depicted in Figure 1. The word cloud simply reflects frequencies of words in the data, which may provide an indication of the importance of related concepts for the participants.

As you move forward with your qualitative analysis and development of your results chapter, we hope that this brief overview of useful tables and figures helps you to decide on an ideal presentation to showcase the trustworthiness your findings. Completing a rigorous qualitative analysis for your dissertation requires many hours of careful interpretation of your data, and your end product should be a rich and detailed results presentation that you can be proud of. Reach out if we can help in any way, as our dissertation coaches would be thrilled to assist as you move through this exciting stage of your dissertation journey!

Anfara Jr., V. A., Brown, K. M., & Mangione, T. L. (2002). Qualitative analysis on stage: Making the research process more public. Educational Researcher , 31 (7), 28-38. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X031007028

Blignault, I., & Ritchie, J. (2009). Revealing the wood and the trees: Reporting qualitative research. Health Promotion Journal of Australia , 20 (2), 140-145. https://doi.org/10.1071/HE09140

Burnard, P., Gill, P., Stewart, K., Treasure, E., & Chadwick, B. (2008). Analysing and presenting qualitative data. British Dental Journal , 204 (8), 429-432. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2008.292

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Qualitative Data Analysis

23 Presenting the Results of Qualitative Analysis

Mikaila Mariel Lemonik Arthur

Qualitative research is not finished just because you have determined the main findings or conclusions of your study. Indeed, disseminating the results is an essential part of the research process. By sharing your results with others, whether in written form as scholarly paper or an applied report or in some alternative format like an oral presentation, an infographic, or a video, you ensure that your findings become part of the ongoing conversation of scholarship in your field, forming part of the foundation for future researchers. This chapter provides an introduction to writing about qualitative research findings. It will outline how writing continues to contribute to the analysis process, what concerns researchers should keep in mind as they draft their presentations of findings, and how best to organize qualitative research writing

As you move through the research process, it is essential to keep yourself organized. Organizing your data, memos, and notes aids both the analytical and the writing processes. Whether you use electronic or physical, real-world filing and organizational systems, these systems help make sense of the mountains of data you have and assure you focus your attention on the themes and ideas you have determined are important (Warren and Karner 2015). Be sure that you have kept detailed notes on all of the decisions you have made and procedures you have followed in carrying out research design, data collection, and analysis, as these will guide your ultimate write-up.

First and foremost, researchers should keep in mind that writing is in fact a form of thinking. Writing is an excellent way to discover ideas and arguments and to further develop an analysis. As you write, more ideas will occur to you, things that were previously confusing will start to make sense, and arguments will take a clear shape rather than being amorphous and poorly-organized. However, writing-as-thinking cannot be the final version that you share with others. Good-quality writing does not display the workings of your thought process. It is reorganized and revised (more on that later) to present the data and arguments important in a particular piece. And revision is totally normal! No one expects the first draft of a piece of writing to be ready for prime time. So write rough drafts and memos and notes to yourself and use them to think, and then revise them until the piece is the way you want it to be for sharing.

Bergin (2018) lays out a set of key concerns for appropriate writing about research. First, present your results accurately, without exaggerating or misrepresenting. It is very easy to overstate your findings by accident if you are enthusiastic about what you have found, so it is important to take care and use appropriate cautions about the limitations of the research. You also need to work to ensure that you communicate your findings in a way people can understand, using clear and appropriate language that is adjusted to the level of those you are communicating with. And you must be clear and transparent about the methodological strategies employed in the research. Remember, the goal is, as much as possible, to describe your research in a way that would permit others to replicate the study. There are a variety of other concerns and decision points that qualitative researchers must keep in mind, including the extent to which to include quantification in their presentation of results, ethics, considerations of audience and voice, and how to bring the richness of qualitative data to life.

Quantification, as you have learned, refers to the process of turning data into numbers. It can indeed be very useful to count and tabulate quantitative data drawn from qualitative research. For instance, if you were doing a study of dual-earner households and wanted to know how many had an equal division of household labor and how many did not, you might want to count those numbers up and include them as part of the final write-up. However, researchers need to take care when they are writing about quantified qualitative data. Qualitative data is not as generalizable as quantitative data, so quantification can be very misleading. Thus, qualitative researchers should strive to use raw numbers instead of the percentages that are more appropriate for quantitative research. Writing, for instance, “15 of the 20 people I interviewed prefer pancakes to waffles” is a simple description of the data; writing “75% of people prefer pancakes” suggests a generalizable claim that is not likely supported by the data. Note that mixing numbers with qualitative data is really a type of mixed-methods approach. Mixed-methods approaches are good, but sometimes they seduce researchers into focusing on the persuasive power of numbers and tables rather than capitalizing on the inherent richness of their qualitative data.

A variety of issues of scholarly ethics and research integrity are raised by the writing process. Some of these are unique to qualitative research, while others are more universal concerns for all academic and professional writing. For example, it is essential to avoid plagiarism and misuse of sources. All quotations that appear in a text must be properly cited, whether with in-text and bibliographic citations to the source or with an attribution to the research participant (or the participant’s pseudonym or description in order to protect confidentiality) who said those words. Where writers will paraphrase a text or a participant’s words, they need to make sure that the paraphrase they develop accurately reflects the meaning of the original words. Thus, some scholars suggest that participants should have the opportunity to read (or to have read to them, if they cannot read the text themselves) all sections of the text in which they, their words, or their ideas are presented to ensure accuracy and enable participants to maintain control over their lives.

Audience and Voice

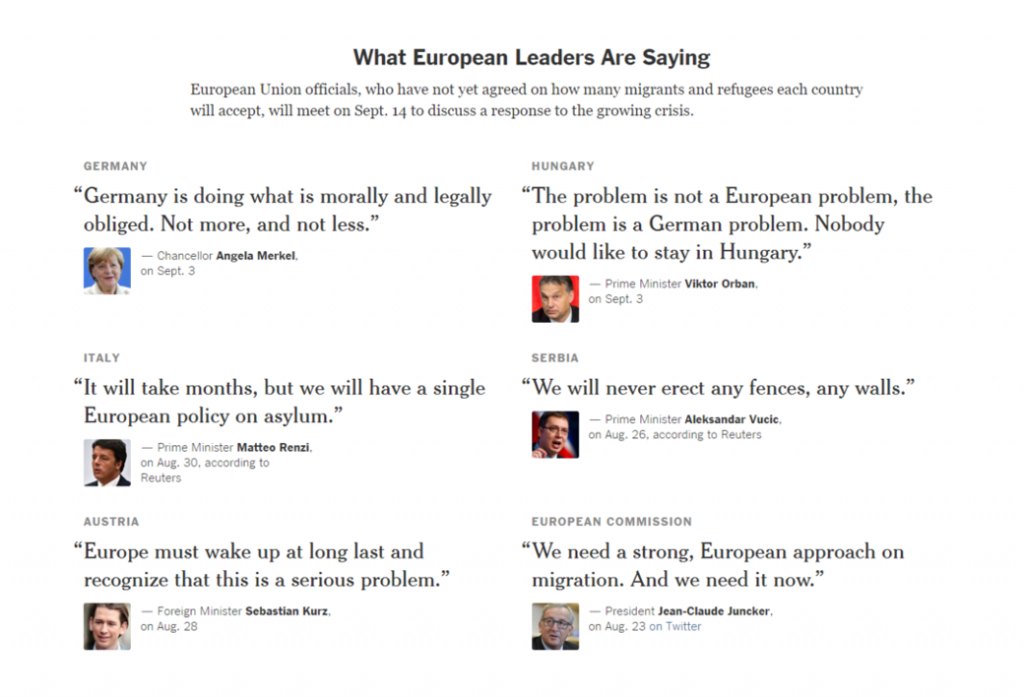

When writing, researchers must consider their audience(s) and the effects they want their writing to have on these audiences. The designated audience will dictate the voice used in the writing, or the individual style and personality of a piece of text. Keep in mind that the potential audience for qualitative research is often much more diverse than that for quantitative research because of the accessibility of the data and the extent to which the writing can be accessible and interesting. Yet individual pieces of writing are typically pitched to a more specific subset of the audience.

Let us consider one potential research study, an ethnography involving participant-observation of the same children both when they are at daycare facility and when they are at home with their families to try to understand how daycare might impact behavior and social development. The findings of this study might be of interest to a wide variety of potential audiences: academic peers, whether at your own academic institution, in your broader discipline, or multidisciplinary; people responsible for creating laws and policies; practitioners who run or teach at day care centers; and the general public, including both people who are interested in child development more generally and those who are themselves parents making decisions about child care for their own children. And the way you write for each of these audiences will be somewhat different. Take a moment and think through what some of these differences might look like.

If you are writing to academic audiences, using specialized academic language and working within the typical constraints of scholarly genres, as will be discussed below, can be an important part of convincing others that your work is legitimate and should be taken seriously. Your writing will be formal. Even if you are writing for students and faculty you already know—your classmates, for instance—you are often asked to imitate the style of academic writing that is used in publications, as this is part of learning to become part of the scholarly conversation. When speaking to academic audiences outside your discipline, you may need to be more careful about jargon and specialized language, as disciplines do not always share the same key terms. For instance, in sociology, scholars use the term diffusion to refer to the way new ideas or practices spread from organization to organization. In the field of international relations, scholars often used the term cascade to refer to the way ideas or practices spread from nation to nation. These terms are describing what is fundamentally the same concept, but they are different terms—and a scholar from one field might have no idea what a scholar from a different field is talking about! Therefore, while the formality and academic structure of the text would stay the same, a writer with a multidisciplinary audience might need to pay more attention to defining their terms in the body of the text.

It is not only other academic scholars who expect to see formal writing. Policymakers tend to expect formality when ideas are presented to them, as well. However, the content and style of the writing will be different. Much less academic jargon should be used, and the most important findings and policy implications should be emphasized right from the start rather than initially focusing on prior literature and theoretical models as you might for an academic audience. Long discussions of research methods should also be minimized. Similarly, when you write for practitioners, the findings and implications for practice should be highlighted. The reading level of the text will vary depending on the typical background of the practitioners to whom you are writing—you can make very different assumptions about the general knowledge and reading abilities of a group of hospital medical directors with MDs than you can about a group of case workers who have a post-high-school certificate. Consider the primary language of your audience as well. The fact that someone can get by in spoken English does not mean they have the vocabulary or English reading skills to digest a complex report. But the fact that someone’s vocabulary is limited says little about their intellectual abilities, so try your best to convey the important complexity of the ideas and findings from your research without dumbing them down—even if you must limit your vocabulary usage.

When writing for the general public, you will want to move even further towards emphasizing key findings and policy implications, but you also want to draw on the most interesting aspects of your data. General readers will read sociological texts that are rich with ethnographic or other kinds of detail—it is almost like reality television on a page! And this is a contrast to busy policymakers and practitioners, who probably want to learn the main findings as quickly as possible so they can go about their busy lives. But also keep in mind that there is a wide variation in reading levels. Journalists at publications pegged to the general public are often advised to write at about a tenth-grade reading level, which would leave most of the specialized terminology we develop in our research fields out of reach. If you want to be accessible to even more people, your vocabulary must be even more limited. The excellent exercise of trying to write using the 1,000 most common English words, available at the Up-Goer Five website ( https://www.splasho.com/upgoer5/ ) does a good job of illustrating this challenge (Sanderson n.d.).

Another element of voice is whether to write in the first person. While many students are instructed to avoid the use of the first person in academic writing, this advice needs to be taken with a grain of salt. There are indeed many contexts in which the first person is best avoided, at least as long as writers can find ways to build strong, comprehensible sentences without its use, including most quantitative research writing. However, if the alternative to using the first person is crafting a sentence like “it is proposed that the researcher will conduct interviews,” it is preferable to write “I propose to conduct interviews.” In qualitative research, in fact, the use of the first person is far more common. This is because the researcher is central to the research project. Qualitative researchers can themselves be understood as research instruments, and thus eliminating the use of the first person in writing is in a sense eliminating information about the conduct of the researchers themselves.

But the question really extends beyond the issue of first-person or third-person. Qualitative researchers have choices about how and whether to foreground themselves in their writing, not just in terms of using the first person, but also in terms of whether to emphasize their own subjectivity and reflexivity, their impressions and ideas, and their role in the setting. In contrast, conventional quantitative research in the positivist tradition really tries to eliminate the author from the study—which indeed is exactly why typical quantitative research avoids the use of the first person. Keep in mind that emphasizing researchers’ roles and reflexivity and using the first person does not mean crafting articles that provide overwhelming detail about the author’s thoughts and practices. Readers do not need to hear, and should not be told, which database you used to search for journal articles, how many hours you spent transcribing, or whether the research process was stressful—save these things for the memos you write to yourself. Rather, readers need to hear how you interacted with research participants, how your standpoint may have shaped the findings, and what analytical procedures you carried out.

Making Data Come Alive

One of the most important parts of writing about qualitative research is presenting the data in a way that makes its richness and value accessible to readers. As the discussion of analysis in the prior chapter suggests, there are a variety of ways to do this. Researchers may select key quotes or images to illustrate points, write up specific case studies that exemplify their argument, or develop vignettes (little stories) that illustrate ideas and themes, all drawing directly on the research data. Researchers can also write more lengthy summaries, narratives, and thick descriptions.

Nearly all qualitative work includes quotes from research participants or documents to some extent, though ethnographic work may focus more on thick description than on relaying participants’ own words. When quotes are presented, they must be explained and interpreted—they cannot stand on their own. This is one of the ways in which qualitative research can be distinguished from journalism. Journalism presents what happened, but social science needs to present the “why,” and the why is best explained by the researcher.

So how do authors go about integrating quotes into their written work? Julie Posselt (2017), a sociologist who studies graduate education, provides a set of instructions. First of all, authors need to remain focused on the core questions of their research, and avoid getting distracted by quotes that are interesting or attention-grabbing but not so relevant to the research question. Selecting the right quotes, those that illustrate the ideas and arguments of the paper, is an important part of the writing process. Second, not all quotes should be the same length (just like not all sentences or paragraphs in a paper should be the same length). Include some quotes that are just phrases, others that are a sentence or so, and others that are longer. We call longer quotes, generally those more than about three lines long, block quotes , and they are typically indented on both sides to set them off from the surrounding text. For all quotes, be sure to summarize what the quote should be telling or showing the reader, connect this quote to other quotes that are similar or different, and provide transitions in the discussion to move from quote to quote and from topic to topic. Especially for longer quotes, it is helpful to do some of this writing before the quote to preview what is coming and other writing after the quote to make clear what readers should have come to understand. Remember, it is always the author’s job to interpret the data. Presenting excerpts of the data, like quotes, in a form the reader can access does not minimize the importance of this job. Be sure that you are explaining the meaning of the data you present.

A few more notes about writing with quotes: avoid patchwriting, whether in your literature review or the section of your paper in which quotes from respondents are presented. Patchwriting is a writing practice wherein the author lightly paraphrases original texts but stays so close to those texts that there is little the author has added. Sometimes, this even takes the form of presenting a series of quotes, properly documented, with nothing much in the way of text generated by the author. A patchwriting approach does not build the scholarly conversation forward, as it does not represent any kind of new contribution on the part of the author. It is of course fine to paraphrase quotes, as long as the meaning is not changed. But if you use direct quotes, do not edit the text of the quotes unless how you edit them does not change the meaning and you have made clear through the use of ellipses (…) and brackets ([])what kinds of edits have been made. For example, consider this exchange from Matthew Desmond’s (2012:1317) research on evictions:

The thing was, I wasn’t never gonna let Crystal come and stay with me from the get go. I just told her that to throw her off. And she wasn’t fittin’ to come stay with me with no money…No. Nope. You might as well stay in that shelter.

A paraphrase of this exchange might read “She said that she was going to let Crystal stay with her if Crystal did not have any money.” Paraphrases like that are fine. What is not fine is rewording the statement but treating it like a quote, for instance writing:

The thing was, I was not going to let Crystal come and stay with me from beginning. I just told her that to throw her off. And it was not proper for her to come stay with me without any money…No. Nope. You might as well stay in that shelter.

But as you can see, the change in language and style removes some of the distinct meaning of the original quote. Instead, writers should leave as much of the original language as possible. If some text in the middle of the quote needs to be removed, as in this example, ellipses are used to show that this has occurred. And if a word needs to be added to clarify, it is placed in square brackets to show that it was not part of the original quote.

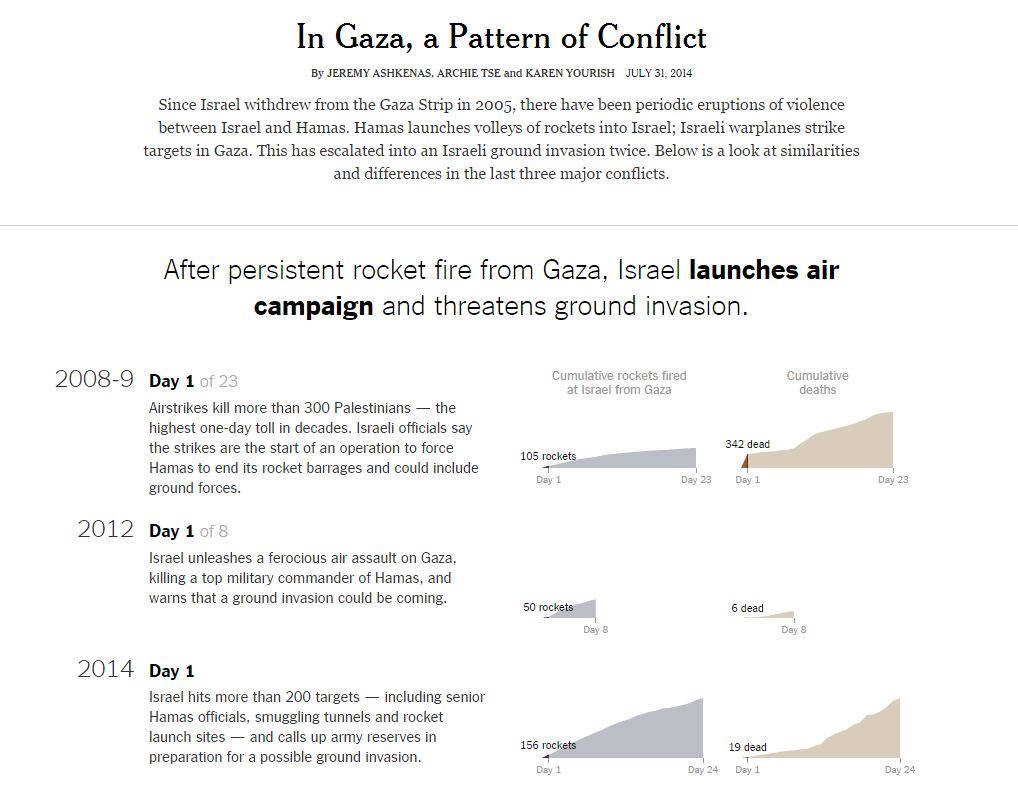

Data can also be presented through the use of data displays like tables, charts, graphs, diagrams, and infographics created for publication or presentation, as well as through the use of visual material collected during the research process. Note that if visuals are used, the author must have the legal right to use them. Photographs or diagrams created by the author themselves—or by research participants who have signed consent forms for their work to be used, are fine. But photographs, and sometimes even excerpts from archival documents, may be owned by others from whom researchers must get permission in order to use them.

A large percentage of qualitative research does not include any data displays or visualizations. Therefore, researchers should carefully consider whether the use of data displays will help the reader understand the data. One of the most common types of data displays used by qualitative researchers are simple tables. These might include tables summarizing key data about cases included in the study; tables laying out the characteristics of different taxonomic elements or types developed as part of the analysis; tables counting the incidence of various elements; and 2×2 tables (two columns and two rows) illuminating a theory. Basic network or process diagrams are also commonly included. If data displays are used, it is essential that researchers include context and analysis alongside data displays rather than letting them stand by themselves, and it is preferable to continue to present excerpts and examples from the data rather than just relying on summaries in the tables.

If you will be using graphs, infographics, or other data visualizations, it is important that you attend to making them useful and accurate (Bergin 2018). Think about the viewer or user as your audience and ensure the data visualizations will be comprehensible. You may need to include more detail or labels than you might think. Ensure that data visualizations are laid out and labeled clearly and that you make visual choices that enhance viewers’ ability to understand the points you intend to communicate using the visual in question. Finally, given the ease with which it is possible to design visuals that are deceptive or misleading, it is essential to make ethical and responsible choices in the construction of visualization so that viewers will interpret them in accurate ways.

The Genre of Research Writing

As discussed above, the style and format in which results are presented depends on the audience they are intended for. These differences in styles and format are part of the genre of writing. Genre is a term referring to the rules of a specific form of creative or productive work. Thus, the academic journal article—and student papers based on this form—is one genre. A report or policy paper is another. The discussion below will focus on the academic journal article, but note that reports and policy papers follow somewhat different formats. They might begin with an executive summary of one or a few pages, include minimal background, focus on key findings, and conclude with policy implications, shifting methods and details about the data to an appendix. But both academic journal articles and policy papers share some things in common, for instance the necessity for clear writing, a well-organized structure, and the use of headings.