Essay on Buddhism

Students are often asked to write an essay on Buddhism in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Buddhism

Introduction to buddhism.

Buddhism is a religion and philosophy that emerged from the teachings of the Buddha (Siddhartha Gautama) around 2,500 years ago in India. It emphasizes personal spiritual development and the attainment of a deep insight into the true nature of life.

Key Beliefs of Buddhism

Buddhism’s main beliefs include the Four Noble Truths, which explain suffering and how to overcome it, and the Noble Eightfold Path, a guide to moral and mindful living.

Buddhist Practices

Buddhist practices like meditation and mindfulness help followers to understand themselves and the world. It encourages love, kindness, and compassion towards all beings.

Impact of Buddhism

Buddhism has greatly influenced cultures worldwide, promoting peace, non-violence, and harmony. It’s a path of practice and spiritual development leading to insight into the true nature of reality.

250 Words Essay on Buddhism

The four noble truths.

At the heart of Buddhism lie the Four Noble Truths. The first truth recognizes the existence of suffering (Dukkha). The second identifies the cause of suffering, primarily desire or attachment (Samudaya). The third truth, cessation (Nirodha), asserts that ending this desire eliminates suffering. The fourth, the path (Magga), outlines the Eightfold Path as a guide to achieve this cessation.

The Eightfold Path

The Eightfold Path, as prescribed by Buddha, is a practical guideline to ethical and mental development with the goal of freeing individuals from attachments and delusions; ultimately leading to understanding, compassion, and enlightenment (Nirvana). The path includes Right Understanding, Right Intent, Right Speech, Right Action, Right Livelihood, Right Effort, Right Mindfulness, and Right Concentration.

Buddhists practice meditation and mindfulness to achieve clarity and tranquility of mind. They follow the Five Precepts, basic ethical guidelines to refrain from harming living beings, stealing, sexual misconduct, lying, and intoxication.

Buddhism is a path of practice and spiritual development leading to insight into the true nature of reality. It encourages individuals to lead a moral life, be mindful and aware of thoughts and actions, and to develop wisdom and understanding. The ultimate goal is the attainment of enlightenment and liberation from the cycle of rebirth and death.

500 Words Essay on Buddhism

Introduction.

Buddhism, a religion and philosophy that emerged from the teachings of the Buddha (Siddhartha Gautama), has become a spiritual path followed by millions worldwide. It is a system of thought that offers practical methodologies and profound insights into the nature of existence.

The Life of Buddha

The Four Noble Truths are the cornerstone of Buddhism. They outline the nature of suffering (Dukkha), its origin (Samudaya), its cessation (Nirodha), and the path leading to its cessation (Magga). These truths present a pragmatic approach, asserting that suffering is an inherent part of existence, but it can be overcome by following the Eightfold Path.

The Eightfold Path, as taught by Buddha, is a practical guideline to ethical and mental development with the goal of freeing individuals from attachments and delusions, ultimately leading to understanding, compassion, and enlightenment. It includes Right Understanding, Right Thought, Right Speech, Right Action, Right Livelihood, Right Effort, Right Mindfulness, and Right Concentration.

Buddhist Schools of Thought

Buddhism and modern science.

The compatibility of Buddhism with modern science has been a topic of interest in recent years. Concepts like impermanence, interconnectedness, and the nature of consciousness in Buddhism resonate with findings in quantum physics, neuroscience, and psychology. This convergence has led to the development of fields like neurodharma and contemplative science, exploring the impact of meditation and mindfulness on the human brain.

Buddhism, with its profound philosophical insights and practical methodologies, continues to influence millions of people worldwide. Its teachings provide a framework for understanding the nature of existence, leading to compassion, wisdom, and ultimately, liberation. As we delve deeper into the realms of modern science, the Buddhist worldview continues to offer valuable perspectives, underscoring its enduring relevance in our contemporary world.

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

One Comment

Leave a reply cancel reply.

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction

The cultural context

- The life of the Buddha

- Suffering, impermanence, and no-self

- The Four Noble Truths

- The law of dependent origination

- The Eightfold Path

- Expansion of Buddhism

- Buddhism under the Guptas and Palas

- The demise of Buddhism in India

- Contemporary revival

- Malaysia and Indonesia

- From Myanmar to the Mekong delta

- Central Asia

- The early centuries

- Developments during the Tang dynasty (618–907)

- Buddhism after the Tang

- Origins and introduction

- Nara and Heian periods

- New schools of the Kamakura period

- The premodern period to the present

- The Himalayan kingdoms

- Buddhism in the West

- Monastic institutions

- Internal organization of the sangha

- Society and state

- Classification of dhammas

- The stages leading to arhatship

- The Pali canon ( Tipitaka )

- Early noncanonical texts in Pali

- Later Theravada literature

- The Buddha: divinization and multiplicity

- The bodhisattva ideal

- The three Buddha bodies

- New revelations

- Madhyamika (Sanlun/Sanron)

- Yogachara/Vijnanavada (Faxiang/Hossō)

- Avatamsaka (Huayan/Kegon)

- Tiantai/Tendai

- Dhyana (Chan/Zen)

- Vajrayana literature

- Rnying-ma-pa

- Sa-skya-pa, Bka’-brgyud-pa, and related schools

- The Bka’-gdams-pa and Dge-lugs-pa

- Traditional literary accounts

- Shakyamuni in art and archaeology

- Literary references

- Art and archaeology

- Mythic figures in the Three Worlds cosmology

- Local gods and demons

- Female deities

- Kings and yogis

- Anniversaries

- Ullambana festival

- New Year and harvest festivals

- Buddhist pilgrimage

- Bodhisattva vows

- Funeral rites

- Protective rites

- Trends since the 19th century

- Challenges and opportunities

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- CORE - Early Buddhism and Gandhara

- Age of the Sage - Transmitting the Wisdoms of the Ages - Buddhism

- World History Encyclopedia - Buddhism

- IndiaNetzone - Buddhism

- Stanford University - Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies - Introduction to Buddhism

- Asia Society - The Origins of Buddhism

- Brown University Library - Basic Concepts of Tibetan Buddhism

- Cultural India - Indian Religions - Buddhism

- Buddhism - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- Buddhism - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

- Who was the founder of Buddhism and what inspired him to create this religion?

- What are the Four Noble Truths and how do they form the foundation of Buddhist philosophy?

- How does the concept of karma work in Buddhism and how does it influence a person's life?

- What is the Eightfold Path and how does it guide Buddhists in their daily lives?

- What are the main branches of Buddhism and how do they differ from each other?

- How has Buddhism spread from its origins in India to become a global religion?

- What role do meditation and mindfulness play in Buddhist practice?

- How does Buddhism view the concept of reincarnation or rebirth?

- What are some of the most important Buddhist texts or scriptures?

- How does Buddhism compare to other major world religions?

- What are some common Buddhist symbols and their meanings?

- How has Buddhism influenced art, literature, and culture in various parts of the world?

Recent News

Buddhism , religion and philosophy that developed from the teachings of the Buddha (Sanskrit: “Awakened One”), a teacher who lived in northern India between the mid-6th and mid-4th centuries bce (before the Common Era). Spreading from India to Central and Southeast Asia , China , Korea , and Japan , Buddhism has played a central role in the spiritual, cultural, and social life of Asia , and, beginning in the 20th century, it spread to the West.

Ancient Buddhist scripture and doctrine developed in several closely related literary languages of ancient India, especially in Pali and Sanskrit . In this article Pali and Sanskrit words that have gained currency in English are treated as English words and are rendered in the form in which they appear in English-language dictionaries. Exceptions occur in special circumstances—as, for example, in the case of the Sanskrit term dharma (Pali: dhamma ), which has meanings that are not usually associated with the term dharma as it is often used in English. Pali forms are given in the sections on the core teachings of early Buddhism that are reconstructed primarily from Pali texts and in sections that deal with Buddhist traditions in which the primary sacred language is Pali. Sanskrit forms are given in the sections that deal with Buddhist traditions whose primary sacred language is Sanskrit and in other sections that deal with traditions whose primary sacred texts were translated from Sanskrit into a Central or East Asian language such as Tibetan or Chinese .

The foundations of Buddhism

Buddhism arose in northeastern India sometime between the late 6th century and the early 4th century bce , a period of great social change and intense religious activity. There is disagreement among scholars about the dates of the Buddha’s birth and death. Many modern scholars believe that the historical Buddha lived from about 563 to about 483 bce . Many others believe that he lived about 100 years later (from about 448 to 368 bce ). At this time in India, there was much discontent with Brahmanic ( Hindu high-caste) sacrifice and ritual . In northwestern India there were ascetics who tried to create a more personal and spiritual religious experience than that found in the Vedas (Hindu sacred scriptures). In the literature that grew out of this movement, the Upanishads , a new emphasis on renunciation and transcendental knowledge can be found. Northeastern India, which was less influenced by Vedic tradition, became the breeding ground of many new sects. Society in this area was troubled by the breakdown of tribal unity and the expansion of several petty kingdoms. Religiously, this was a time of doubt, turmoil, and experimentation.

A proto-Samkhya group (i.e., one based on the Samkhya school of Hinduism founded by Kapila ) was already well established in the area. New sects abounded, including various skeptics (e.g., Sanjaya Belatthiputta), atomists (e.g., Pakudha Kaccayana), materialists (e.g., Ajita Kesakambali), and antinomians (i.e., those against rules or laws—e.g., Purana Kassapa). The most important sects to arise at the time of the Buddha, however, were the Ajivikas (Ajivakas), who emphasized the rule of fate ( niyati ), and the Jains , who stressed the need to free the soul from matter. Although the Jains, like the Buddhists, have often been regarded as atheists, their beliefs are actually more complicated. Unlike early Buddhists, both the Ajivikas and the Jains believed in the permanence of the elements that constitute the universe, as well as in the existence of the soul.

Despite the bewildering variety of religious communities , many shared the same vocabulary— nirvana (transcendent freedom), atman (“self” or “soul”), yoga (“union”), karma (“causality”), Tathagata (“one who has come” or “one who has thus gone”), buddha (“enlightened one”), samsara (“eternal recurrence” or “becoming”), and dhamma (“rule” or “law”)—and most involved the practice of yoga. According to tradition, the Buddha himself was a yogi—that is, a miracle-working ascetic .

Buddhism, like many of the sects that developed in northeastern India at the time, was constituted by the presence of a charismatic teacher, by the teachings this leader promulgated , and by a community of adherents that was often made up of renunciant members and lay supporters. In the case of Buddhism, this pattern is reflected in the Triratna —i.e., the “Three Jewels” of Buddha (the teacher), dharma (the teaching), and sangha (the community).

In the centuries following the founder’s death, Buddhism developed in two directions represented by two different groups. One was called the Hinayana (Sanskrit: “Lesser Vehicle”), a term given to it by its Buddhist opponents. This more conservative group, which included what is now called the Theravada (Pali: “Way of the Elders”) community, compiled versions of the Buddha’s teachings that had been preserved in collections called the Sutta Pitaka and the Vinaya Pitaka and retained them as normative. The other major group, which calls itself the Mahayana (Sanskrit: “Greater Vehicle”), recognized the authority of other teachings that, from the group’s point of view, made salvation available to a greater number of people. These supposedly more advanced teachings were expressed in sutras that the Buddha purportedly made available only to his more advanced disciples .

As Buddhism spread, it encountered new currents of thought and religion. In some Mahayana communities, for example, the strict law of karma (the belief that virtuous actions create pleasure in the future and nonvirtuous actions create pain) was modified to accommodate new emphases on the efficacy of ritual actions and devotional practices. During the second half of the 1st millennium ce , a third major Buddhist movement, Vajrayana (Sanskrit: “Diamond Vehicle”; also called Tantric, or Esoteric , Buddhism), developed in India. This movement was influenced by gnostic and magical currents pervasive at that time, and its aim was to obtain spiritual liberation and purity more speedily.

Despite these vicissitudes , Buddhism did not abandon its basic principles. Instead, they were reinterpreted, rethought, and reformulated in a process that led to the creation of a great body of literature. This literature includes the Pali Tipitaka (“Three Baskets”)—the Sutta Pitaka (“Basket of Discourse”), which contains the Buddha’s sermons; the Vinaya Pitaka (“Basket of Discipline”), which contains the rule governing the monastic order; and the Abhidhamma Pitaka (“Basket of Special [Further] Doctrine”), which contains doctrinal systematizations and summaries. These Pali texts have served as the basis for a long and very rich tradition of commentaries that were written and preserved by adherents of the Theravada community. The Mahayana and Vajrayana traditions have accepted as Buddhavachana (“the word of the Buddha”) many other sutras and tantras , along with extensive treatises and commentaries based on these texts. Consequently, from the first sermon of the Buddha at Sarnath to the most recent derivations, there is an indisputable continuity—a development or metamorphosis around a central nucleus—by virtue of which Buddhism is differentiated from other religions.

Home — Essay Samples — Religion — Buddhism

Essays on Buddhism

The pros and cons of buddhism, mandala: a journey into self-understanding, made-to-order essay as fast as you need it.

Each essay is customized to cater to your unique preferences

+ experts online

The Belief in Karma: How Our Deeds Shape Destiny

Buddhism and christianity: compare and contrast paper, the importance of karma, exploring the transformative power of mandalas, let us write you an essay from scratch.

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Ninian Smart’s Seven Dimensions in Buddhism

Taoism vs. buddhism, why i believe in the concept of karma, do you believe in karma: philosophical and cultural perspectives, get a personalized essay in under 3 hours.

Expert-written essays crafted with your exact needs in mind

Philosophy of The Self: Western Science and Eastern Karma

The teaching of buddha: sayings and thoughts, the story of siddhartha gautama - the buddha, the great of buddha: the history of building, siddhartha gautama: the path of becoming buddha, history and early development of buddhism, buddhism - role of the gods, buddha's life as an example to become a better person, buddha: the story of creating 5 main morals, topics in this category.

- Zen Buddhism

Popular Categories

- World Religions

- Religious Concepts

- Christianity

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- Utility Menu

GA4 Tracking Code

- Introduction

- Buddhism in America

- The Buddhist Experience

- Issues for Buddhists in America

The Path of Awakening

Prince Siddhartha: Renouncing the World

Becoming the “Buddha”: The Way of Meditation

The Dharma: The Teachings of the Buddha

The Sangha: The Buddhist Community

The Three Treasures

The Expansion of Buddhism

As Buddhism spread through Asia, it formed distinct streams of thought and practice: the Theravada ("The Way of the Elders" in South and Southeast Asia), the Mahayana (the “Great Vehicle” in East Asia), and the Vajrayana (the “Diamond Vehicle” in Tibet), a distinctive and vibrant form of Mahayana Buddhism that now has a substantial following. ... Read more about The Expansion of Buddhism

Theravada: The Way of the Elders

Mahayana: The Great Vehicle

Vajrayana: The Diamond Vehicle

Buddhists in the American West

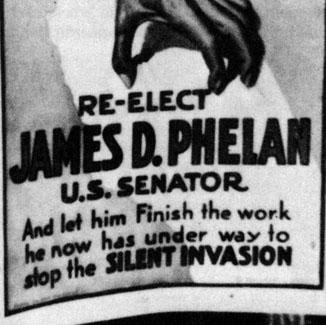

Discrimination and Exclusion

East Coast Buddhists

At the 1893 World’s Parliament of Religions

The 1893 World’s Parliament of Religions, held at that year's Chicago World’s Fair, gave Buddhists from Sri Lanka and Japan the chance to describe their own traditions to an audience of curious Americans. Some stressed the universal characteristics of Buddhism, and others criticized anti-Japanese sentiment in America. ... Read more about At the 1893 World’s Parliament of Religions

Internment Crisis

Building “American Buddhism”

New Asian Immigration and the Temple Boom

Popularizing Buddhism

The Image of the Buddha

Ever since the first century, Buddhists have created images and other depictions of the Buddha in metal, wood, and stone with stylized hand-positions called mudras . Images of the Buddha are often the focus of reverence and devotion. ... Read more about The Image of the Buddha

The Practice of Mindfulness

People commonly equate Buddhism with meditation, but historically very few Buddhists meditated. Those who did, however, drew from a long and rich tradition of Buddhist philosophical and contemplative practice. ... Read more about The Practice of Mindfulness

One Hand Clapping?

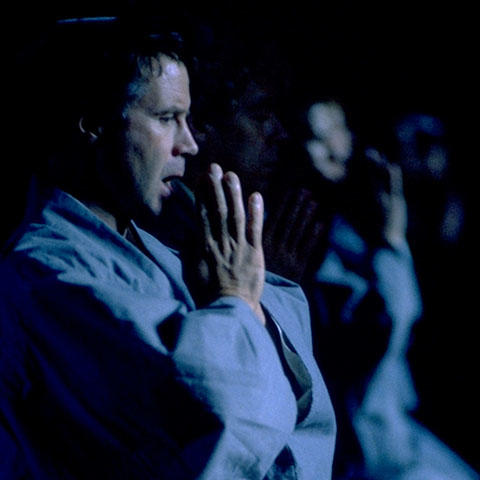

Sesshin: A Meditation Retreat

Intensive Zen meditation retreats, or sesshins , such as one in Mt. Temper, New York, are designed for participants to focus intensively on monastic Buddhist practice and meditation. Retreats include many rituals to allow students to fully immerse themselves in their practice—even during mealtime. ... Read more about Sesshin: A Meditation Retreat

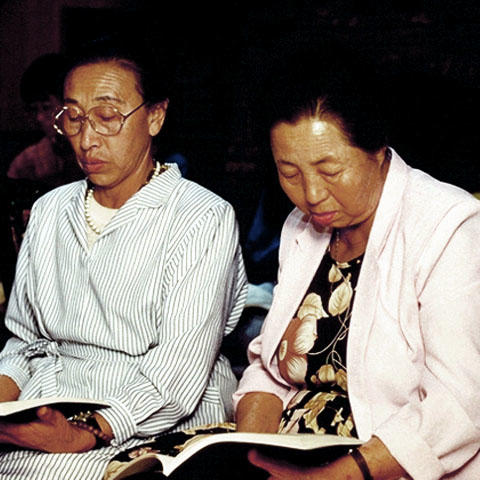

Chanting the Sutras

Chanting scriptures and prayers to buddhas and bodhisattvas is a central practice in all streams of Buddhism, intended both to reflect upon content and to focus the mind. ... Read more about Chanting the Sutras

Creating a Mandala

Becoming a Monk

The many streams of Buddhism differ in their approaches to monasticism and initiation rituals. For example, is it common in the Theravada tradition for young men to become novice monks as a rite of passage into adulthood. In some Mahayana traditions, women can take the Triple Platform Ordination and become nuns. Meanwhile, in some Japanese traditions, priests and masters can marry and have children. ... Read more about Becoming a Monk

From Street Gangs to Temple

In Southern California, some Theravada temples have taken up the practice of granting temporary novice ordinations to Cambodian American gang members, with the hope of reorienting the youth toward their families’ religion and culture. ... Read more about From Street Gangs to Temple

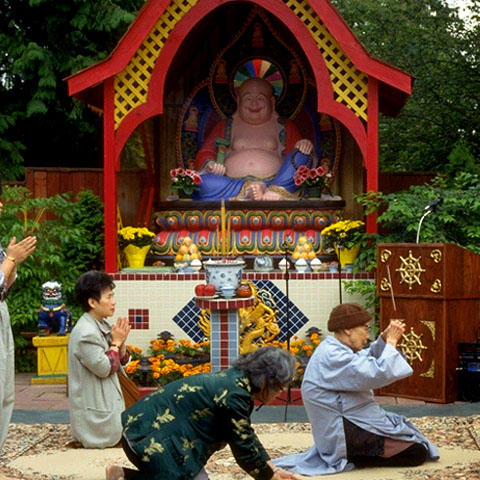

Devotion to Guanyin

The compassionate bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara, also known as Guanyin, is central to the practice of Chinese and Vietnamese Buddhists in America. A bodhisattva is an enlightened one who remains engaged in the world in order to enlighten all beings, and Buddhists channel the bodhisattva Guanyin by cultivating compassion for all beings in the world. ... Read more about Devotion to Guanyin

Buddha’s Birthday

Buddhists often consider the Buddha’s birthday an occasion for celebration, and Chinese, Thai, and Japanese temples in America all celebrate differently. ... Read more about Buddha’s Birthday

Remembering the Ancestors

Celebrating the New Year

Although the Lunar New Year is not a particularly “Buddhist” holiday, many Thai and Chinese Buddhists observe the occasion with celebration and visits to family and activities at Buddhist temples. ... Read more about Celebrating the New Year

Building a Pure Land on Earth

Pure Land Buddhists pay respect to Amitabha, the Buddha of Infinite Light, who created a paradise for Buddhist devotees called the “Land of Bliss.” Pure Land Buddhists in America seek to create a Pure Land here on Earth through ritual acts of devotion, care for animals and human beings, study, meditation, and acting compassionately in the public sphere. ... Read more about Building a Pure Land on Earth

Monastery in the Hudson Valley

The Chuang Yen Monastery in Kent, New York, is a prime example of how Chinese Buddhism has flourished in America, in all its richness and complexity. ... Read more about Monastery in the Hudson Valley

One Buddhism? Or Multiple Buddhisms?

There are two distinct but related histories of American Buddhism: that of Asian immigrants and that of American converts. The presence of the two communities raises such questions as: What is the difference between the Buddhism of American converts and Buddhism of Asian immigrant communities? How do we characterize the Buddhism of a new generation Asian-American youth—as a movement of preservation or transformation? ... Read more about One Buddhism? Or Multiple Buddhisms?

The Difficulties of a Monk

A reflection on American Buddhist monasticism from the Venerable Walpola Piyananda highlights the tensions that arise when immigrant Buddhism encounters American social customs that differ from those in Asia. ... Read more about The Difficulties of a Monk

Changing Patterns of Authority

American convert Buddhism and immigrant Asian Buddhism have dramatically different models of authority and institutional hierarchy. Buddhist organizations and communities in America are forced to attend to the question of how spiritual, social, financial, and organizational authorities will be dispersed among its leaders and members. ... Read more about Changing Patterns of Authority

Women in American Buddhism

American Buddhism has created new roles for women in the Buddhist tradition. American Buddhist women have been active in movements to revive the ordination lineages of Buddhist nuns in the Theravada and Vajrayana traditions. ... Read more about Women in American Buddhism

Buddhism and Social Action: Engaged Buddhism

Pioneered by the Vietnamese monk Thich Nhat Hanh in the 1970s, “Engaged Buddhism” brings a Buddhist perspective to the ongoing struggle for social and environmental justice in America. ... Read more about Buddhism and Social Action: Engaged Buddhism

Ecumenical and Interfaith Buddhism: Coming Together in America

Since the 1970s, Buddhist leaders from various traditions have engaged together in ecumenical councils and organizations to address prevalent challenges for Buddhism in North America. These events have brought together Buddhist traditions that, in the past, have had limited contact with one another. In addition, these groups have become involved in interfaith partnerships, particularly with Christian and Jewish organizations. ... Read more about Ecumenical and Interfaith Buddhism: Coming Together in America

Teaching the Love of Buddha: The Next Generation

How do Buddhists in America transmit their culture and tradition to new generations? In the Jodo Shinshu school of Japanese Buddhism, Sunday School classes have become an important religious educational tool to address this question, and its curriculum offers a particularly American approach to educating children about their tradition. ... Read more about Teaching the Love of Buddha: The Next Generation

Image Gallery

Awe and dread: How religions have responded to total solar eclipses over the centuries

Silicon valley start-up aims to unlock buddhist jhana states with tech, how lakshmi, the goddess of wealth and fortune, is depicted in jainism and buddhism.

- Avalokiteshvara

- Bhaishajya-guru

- Shinran Shonin

- Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche

Buddhism Timeline

7627213d930e1981366069359e5a876e, buddhism in the world (text), ca. 6th-5th c. bce life of siddhartha gautama, the buddha.

The dates of the Buddha remain a point of controversy within both the Buddhist and scholarly communities. Though many scholars today place the Buddha’s life between 460-380 BCE, according to one widely accepted traditional account, Siddhartha was born as a prince in the Shakya clan in 563 BCE. After achieving enlightenment at the age of 36, the Buddha spent the remainder of his life giving spiritual guidance to an ever-growing body of disciples. He is said to have entered into parinirvana (nirvana after death) in 483 BCE at the age of 81.

c. 480-380 BCE The First Council

Though specific dates are uncertain, a group of the Buddha’s disciples is said to have come together shortly after the Buddha’s parinirvana in hopes of establishing guidelines to ensure the continuity of the Sangha. According to tradition, as many as 500 prominent arhats gathered in Rajagriha to recite together and standardize the Buddha’s sutras (discourses on Dharma) and vinaya (rules of conduct).

c. 350 BCE The Second Council

It remains unclear if what is known as the Second Council refers to one particular assemblage of monks or if there were several meetings convened during the 4th century BCE to clarify points of controversy. It also remains unclear precisely what matters of doctrine or conduct were in dispute. What is clear is that this council resulted in the first schism in the Sangha, between the Sthaviravada and the Mahasanghika.

269-232 BCE The Spread of Buddhism Through South Asia

After witnessing the great bloodshed and suffering caused by his military campaigns, Indian Emperor Ashoka Maurya converted to Buddhism, sending missionaries throughout India and into present day Sri Lanka.

200 BCE-200 CE Emergence of Two Schools of Buddhism

Differing interpretations of the Buddha’s teachings resulted in the development of two main schools of Buddhism. The first branch, Mahayana, referred to itself as the “Great Vehicle,” and is today principally found in China, Korea, and Japan. The second branch comprised 18 schools, of which only one exists today — Theravada, or the “Way of the Elders.” Theravada Buddhism is presently followed in Sri Lanka, Burma, Thailand, Cambodia, and Laos.

65 CE First Mention of Buddhism in China

Han dynasty records note that Prince Ying of Ch’u, a half-brother of the Han emperor, provided a vegetarian feast for the Buddhist laity and monks living in his kingdom around 65 CE. This indicates that a Buddhist community had already formed there.

c. 100 CE Ashvaghosha Writes Buddhacarita

Among the early biographies of the Buddha was the Buddhacarita, written in Sanskrit by the Indian poet Ashvaghosha. Buddhacarita, literally “Life of the Buddha,” is regarded as one of the greatest epic poems of all history.

200s CE Nagarjuna Founds the Madhyamaka School

Nagarjuna is one of the most important philosophers of the Buddhist tradition. Based on his reading of the Perfection of Wisdom sutras, Nagarjuna argued that everything in the world is fundamentally sunya, or “empty” — that is, without inherent existence. This idea that the world is real yet radically impermanent and interdependent has played a central role in Buddhist philosophy.

372 CE Buddhism Introduced to Korea from China

In 372 CE the Chinese king Fu Chien sent a monk-envoy, Shun-tao, to the Koguryo court with Buddhist scriptures and images. Although all three of the kingdoms on the Korean peninsula soon embraced Buddhism, it was not until the unification of the peninsula under the Silla in 668 CE that the tradition truly flourished.

400s CE Buddhaghosa Systematizes Theravada Teachings

Buddhaghosa was a South Indian monk who played a formative role in the systematization of Theravada doctrine. After arriving in Sri Lanka in the early part of the fifth century CE, he devoted himself to editing and translating into Pali the scriptural commentaries that had accumulated in the native Sinhalese language. He also composed the Visuddhimagga, “Path of Purity,” an influential treatise on Theravada practice. From this point on, Theravada became the dominant form of Buddhism in Sri Lanka and eventually spread to Southeast Asia.

402 CE Pure Land Buddhism Established in China

In 402 CE, Hui-yuan became the first Chinese monk to form a group specifically devoted to reciting the vow to be reborn in the Western Paradise, and founded the Donglin Temple at Mount Lu for this purpose. Subsequent practitioners of Pure Land Buddhism regard Hui-yuan as the school’s founder.

520 CE Bodhidharma and Ch’an (Zen) in China

The Ch’an (Zen) school attributes its establishment to the arrival of the monk Bodhidharma in Northern China in 520 CE. There, he is said to have spent nine years meditating in front of a wall before silently transmitting the Buddha’s Dharma to Shen-Kuang, the second patriarch. All Zen masters trace their authority to this line.

552 CE Buddhism Enters Japan from Korea

In 552 CE the king of Paekche sent an envoy to Japan in hopes of gaining military support. As gifts, he sent an image of Buddha, several Buddhist scriptures, and a memorial praising Buddhism. Within three centuries of this introduction, Buddhism would become the major spiritual and intellectual force in Japan.

700s CE Vajrayana Buddhism Emerges in Tibet

Buddhist teachings and practices appear to have first made their way into Tibet in the mid-7th century CE. During the reign of King Khri-srong (c. 740-798 CE), the first Tibetan monastery was founded and the first monk ordained. For the next four hundred years, a constant flow of Tibetan monks made their way to Northern India to study at the great Buddhist universities. It was from the university of Vikramasila around the year 767 that the yogin-magician Padmasambhava is said to have carried the Vajrayana teachings to Tibet, where they soon became the dominant form of Buddhism.

1044-1077 CE Theravada Buddhism Established in Burma

Theravada Buddhism was practiced in pockets of southern Burma since about the 6th century CE. However, when King Anawrahta ascended the throne in 1044, Shin Arahan, a charismatic Mon monk from Southern Burma, convinced the new monarch to establish a more strictly Theravadin expression of Buddhism for the entire kingdom. From that time on, Theravada would remain the tradition of the majority of the Burmese people.

c. 1050 CE Development of Jogye Buddhism in Korea

The Ch’an school, which first arrived in Korea from China in the 8th century CE, eventually established nine branches, known as the Nine Mountains. In the 11th century, these branches were organized into one system under the name of Jogye. Although all Buddhist teachings were retained, the kong-an (koan) practice of Lin-chi Yixuan gained highest stature as the most direct path to enlightenment.

1100s CE Pure Land Buddhism Established in Japan

Following a reading of a Chinese Pure Land text, the Japanese monk Honen Shonin (1133-1212 CE) became convinced that the only effective mode of practice was nembutsu: chanting the name of Amitabha Buddha. This soon became a dominant form of Buddhist practice in Japan.

1100s CE Rinzai School of Zen Buddhism Established in Japan

In the 12th century CE, a Japanese monk named Eisai returned from China, bringing with him both green tea and the Rinzai school of Zen Buddhism. In the form of meditation practiced by this school, the student’s only guidance is to come from the subtle hint of a raised eyebrow, the sudden jolt of an unexpected slap, or the teacher’s direct questioning on the meaning of a koan.

1203 CE Destruction of Buddhist Centers in India

By the close of the first millennium CE, Buddhism had passed its zenith in India. Traditionally, the end of Indian Buddhism is identified with the advent of Muslim Rule in Northern India. The Turk Muhammad Ghuri razed the last two great Buddhist universities, Nalanda and Vikramasila, in 1197 and 1203 respectively. However, recent histories have suggested that the destruction of these monasteries was militarily, rather than religiously, motivated.

1200s CE True Pure Land Buddhism Established

Honen’s disciple Shinran Shonin (1173-1262 CE) began the devotional “True Pure Land” movement in the 13th century CE. Considering the lay/monk distinction invalid, Shinran married and had several children, thereby initiating the practice of married Jodo Shinshu clergy and establishing a familial lineage of leadership — traits which continue to distinguish the school to this day.

1200s CE Dōgen Founds Soto Zen in Japan

Dōgen (1200-1253 CE), an influential Japanese priest and philosopher, spent most of his two years in China studying T’ien-t’ai Buddhism. Disappointed by the intellectualism of the school, he was about to return to Japan when the Ts’ao-tung monk Ju-ching (Rujing) explained that the practice of Zen simply meant “dropping off both body and mind.” Dōgen, immediately enlightened, returned to Japan, establishing Soto (the Japanese pronunciation of the Chinese graphs for Ts’ao-tung) as one of the pre-eminent schools.

1253 CE Nichiren Buddhism Established in Japan

As the sun began to rise on May 17, 1253 CE, Nichiren Daishonin climbed to the crest of a hill, where he cried out “Namu Myoho Renge Kyo,” “Adoration to the Sutra of the Lotus of the Perfect Truth.” Nichiren considered the recitation of this mantra to be the core of the true teachings of the Buddha. He believed that it would eventually spread throughout the world, a conviction sustained by contemporary sects of the Nichiren school, especially the Soka Gakkai.

1279-1360 CE Theravada Buddhism Established in Southeast Asia

With Kublai Khan’s conquest of China in the thirteenth century CE, ever greater numbers of Tai migrated from southwestern China into present day Thailand and Burma. There, they established political domination over the indigenous Mon and Khmer peoples, while appropriating elements of these cultures, including their Buddhist faith. By the time that King Rama Khamhaeng had ascended the throne in Sukhothai (central Thailand) in 1279, a monk had been sent to Sri Lanka to receive Theravadin texts. During the reigns of Rama Khamhaeng’s son and grandson, Sinhala Buddhism spread northward to the Tai Kingdom of Chiangmai. Within a century, the royal houses of Cambodia and Laos also became Theravadin.

1391-1474 CE The First Dalai Lama

Gedun Drupa (1391-1474 CE), a Tibetan monk of great esteem during his lifetime, was considered after his death to have been the first Dalai Lama. He founded the major monastery of Tashi Lhunpo at Shigatse, which would become the traditional seat of Panchen Lamas (second only to the Dalai Lama).

1881 CE Founding of Pali Text Society

Ever since its founding by the British scholar T.W. Rhys Davids in 1881 CE, the Pali Text Society has been the primary publisher of Theravada texts and translations into Western languages.

1891 CE Anagarika Dharmapala Founds Mahabodhi Society

Sri Lankan writer Anagarika Dharmapala played an important role in restoring Bodh-Gaya, the site of the Buddha’s enlightenment, which had badly deteriorated after centuries of neglect. In order to raise funds for this project, Dharmapala founded the Mahabodhi Society, first in Ceylon and later in India, the United States, and Britain. He also edited the society’s periodical, The Mahabodhi Journal.

1930 CE Soka Gakkai Established in Japan

Soka Gakkai is a Japanese Buddhist movement that was begun in 1930 CE by an educator named Tsunesaburo Makiguchi. Soon after its founding, it became associated with Nichiren Shoshu, a sect of Nichiren Buddhism. Today the organization has over twelve million members around the world.

1938 CE Rissho Kosei-Kai Established in Japan

The Rissho Kosei-Kai movement was founded by the Rev. Nikkyo Niwano in 1938 CE, and is based on the teachings set forth in the Lotus Sutra and works for individual and world peace. Rev. Niwano was awarded the Templeton Prize for Progress in Religion in 1979 and honored by the Vatican in 1992. The Rissho Kosei-Kai has since been active in interfaith activities throughout the world.

1949 CE Buddhist Sangha Flees Mainland China

With the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, Buddhist monks and nuns fled to Hong Kong, Taiwan, Malaysia, and Singapore. Many of these monks and nuns subsequently immigrated to Australia, Europe and the United States.

1950 CE World Fellowship of Buddhists Inaugurated in Sri Lanka

The World Fellowship of Buddhists was established in 1950 CE in Sri Lanka to bring Buddhists together in promoting common goals. Since 1969, its permanent headquarters have been in Thailand, with regional offices in 34 different countries.

1956 CE Buddhist Conversions in India

On October 14, 1956 CE, Bhim Rao Ambedkar (1891-1956), India’s leader of Hindu untouchables, publicly converted to Buddhism as part of a political protest. As many as half a million of his followers also took the three refuges and five precepts on that day. In the following years, over four million Indians, chiefly from the castes of untouchables, declared themselves Buddhists.

1959 CE Dalai Lama Flees to India

With the Chinese occupation of Tibet, the Dalai Lama, the Karmapa, and other Vajrayana Buddhist leaders fled to India. A Tibetan government in exile was established in Dharamsala, India.

1966 CE Thich Nhat Hanh Visits the U.S. and Western Europe

Thich Nhat Hanh is a Vietnamese monk, teacher, and peace activist. While touring the U.S. in 1966, Nhat Hanh was outspoken against the American-supported Saigon government. As a result of his criticism, Nhat Hanh faced certain imprisonment upon his return to Vietnam. He therefore decided to take asylum in France, where he founded Plum Village, today an important center for meditation and action.

1975 CE Devastation of Buddhism in Cambodia

Pol Pot’s Marxist regime came to power in Cambodia in 1975 CE. Over the four years of his governance, most of Cambodia’s 3,600 Buddhist temples were destroyed. The Sangha was left with an estimated 3,000 of its 50,000 monks. The rest did not survive the persecution.

1989 CE Founding of the International Network of Engaged Buddhists (INEB)

The International Network of Engaged Buddhists (INEB) began in Thailand in 1989 as a conference of 36 monks and lay persons from 11 countries. Today, it has expanded to 160 members and affiliates from 26 countries. As its name suggests, INEB endeavors to facilitate Buddhist participation in social action in order to create a just and peaceful world.

1989 CE Dalai Lama Receives Nobel Peace Prize

Tenzin Gyatso, the Fourteenth Dalai Lama, was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1989 for his tireless work spreading a message of non-violence. He has said on many occasions about Buddhism, “My religion is very simple – my religion is kindness.”

2010 CE Western Buddhist Teachers call for U.S. Commission of Inquiry to Burma

In 2010, prominent Buddhist teachers in the U.S. signed a letter to President Barack Obama urging him to repudiate the results of the upcoming Burmese election, in light of crimes against ethnic groups committed by the Burmese military regime.

With over 520 million followers, Buddhism is currently the world’s fourth-largest religious tradition. Though Theravada and Mahayana are its two major branches, contemporary Buddhism comprises a wide diversity of practices, beliefs, and traditions — both throughout East and Southeast Asia and worldwide.

Buddhism in America (text)

1853 ce the first chinese temple in “gold mountain”.

Attracted by the 1850s Gold Rush, many Chinese workers and miners came to California, which they called “Gold Mountain” — and brought their Buddhist and Taoist traditions with them. In 1853, they built the first Buddhist temple in San Francisco’s Chinatown. By 1875, Chinatown was home to eight temples, and by the end of the century, there were hundreds of Chinese temples and shrines along the West Coast.

1878 CE Kuan-yin in Hawaii

In 1878, the monk Leong Dick Ying brought to Honolulu gold-leaf images of the Taoist sage Kuan Kung and the bodhisattva of compassion Kuan-yin. He thus established the Kuan-yin Temple, which is the oldest Chinese organization in Hawaii. The Temple has been located on Vineland Avenue in Honolulu since 1921.

1879 CE The Light of Asia Comes West

Sir Edwin Arnold’s The Light of Asia, a biography of the Buddha in verse, was published in 1879. This immensely popular book, which went through eighty editions and sold over half a million copies, gave many Americans their first introduction to the Buddha.

1882 CE The Chinese Exclusion Act

Two decades of growing anti-Chinese sentiment in the U.S. led to the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882. The act barred new Chinese immigration for ten years, including that by women trying to join their husbands who were already in the U.S., and prohibited the naturalization of Chinese people.

1893 CE Buddhists at the Parliament of the World’s Religions

The 1893 Parliament of the World’s Religions, held in Chicago in conjunction with the World Columbian Exposition, included representatives of many strands of the Buddhist tradition: Anagarika Dharmapala (Sri Lankan Maha Bodhi Society), Shaku Soyen (Japanese Rinzai Zen), Toki Horyu (Shingon), Ashitsu Jitsunen (Tendai), Yatsubuchi Banryu (Jodo Shin), and Hirai Kinzo (a Japanese lay Buddhist). Days after the Parliament, in a ceremony conducted by Anagarika Dharmapala, Charles T. Strauss of New York City became the first person to be ordained into the Buddhist Sangha on American soil.

1894 CE The Gospel of Buddha

The Gospel of Buddha was an influential book published by Paul Carus in 1894. The book brought a selection of Buddhist texts together in readable fashion for a popular audience. By 1910, The Gospel of Buddha had been through 13 editions.

1899 CE Jodo Shinshu Buddhism and the Buddhist Churches of America

The Young Men’s Buddhist Association (Bukkyo Seinenkai), the first Japanese Buddhist organization on the U.S. mainland, was founded in 1899 under the guidance of Jodo Shinshu missionaries Rev. Dr. Shuya Sonoda and Rev. Kakuryo Nishijima. The following years saw temples established in Sacramento (1899), Fresno (1900), Seattle (1901), Oakland (1901), San Jose (1902), Portland (1903), and Stockton (1906). This organization, initially called the Jodo Shinshu Buddhist Mission of North America, went on to become the Buddhist Churches of America (incorporated in 1944). Today, it is the largest Buddhist organization serving Japanese-Americans, entailing some 60 temples and a membership of about 19,000.

1900 CE First Non-Asian Buddhist Association

In 1900, a group of Euro-Americans attracted to the Buddhist teachings of the Jodo Shinshu organized the Dharma Sangha of the Buddha in San Francisco.

1915 CE World Buddhist Conference

Buddhists from throughout the world gathered in San Francisco in August 1915 at a meeting convened by the Jodo Shinshu Buddhist Mission of North America. Resolutions from the conference were taken to President Woodrow Wilson.

1931 CE Sokei-an and Zen in New York

The Buddhist Society of America was incorporated in New York in 1931 under the guidance of Rinzai Zen teacher Sokei-an. Sokei-an first came to the U.S. in 1906 to study with Shokatsu Shaku in California, though he completed his training in Japan where he was ordained in 1931. Sokei-an died of poor health in 1945, after having spent two years in a Japanese internment camp. The center he established in New York City would evolve into the First Zen Institute of America.

1935 CE Relics of the Buddha to San Francisco

In 1935, a portion of the Buddha’s relics was presented to Bishop Masuyama of the Jodo Shinshu Buddhist Mission of North America, based in San Francisco. This led to the construction of a new Buddhist Church of San Francisco, with a stupa on its roof for the holy relics, located on Pine Street and completed in 1938.

1942 CE Internment of Japanese Americans

Two months after Pearl Harbor, President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 which eventually removed 120,000 Japanese Americans, both citizens and noncitizens, to internment camps where they remained until the end of World War II. Buddhist priests and other community leaders were among the first to be targeted and evacuated. Zen teachers Sokei-an and Nyogen Senzaki were both interned. Buddhist organizations continued to serve the internees in the camps.

1949 CE Buddhist Studies Center in Berkeley

The Buddhist Studies Center was first established in 1949 in Berkeley, California, under the auspices of the Buddhist Churches of America. In 1966, the center changed its name to the Institute of Buddhist Studies and became the first seminary for Buddhist ministry and research. The Institute affiliated with the Graduate Theological Union in 1985, and today is active in training clergy for the Buddhist Churches of America.

1955 CE Beat Zen and Zen Literature

The Beat Movement was started by American authors who explored American pop culture and politics in the post-war era, with strong themes from Eastern spirituality. The first public reading of the poem “Howl” by Allen Ginsberg in 1955 at the Six Gallery in San Francisco is said to have signalled the beginning of the Beat Zen movement. The late 1950s also saw a Zen literary boom in the U.S. Several popular books on Buddhism were published, including Alan Watt’s bestseller The Way of Zen and Jack Kerouac’s The Dharma Bums.

1960 CE Soka Gakkai in the U.S.

Daisaku Ikeda, President of Soka Gakkai, visited the United States in 1960, largely introducing Soka Gakkai to Americans. By 1992, Soka Gakkai International–USA estimated that it had 150,000 American members.

1965 CE Immigration and Nationality Act

The 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act ended the quota system which had virtually halted immigration from Asia to the United States for over forty years. Following 1965, growing numbers of Asian immigrants from South, Southeast, and East Asia settled in America; many brought Buddhist traditions with them.

1966 CE The Vietnam Conflict and Thich Nhat Hanh in America

The Vietnam conflict incited a surge of Buddhist activism in Saigon, which included some monks immolating themselves as an act of protest. In response, U.S. Secretary of State Henry Cabot Lodge met with Vietnamese and Japanese Buddhist leaders, and the State Department established an Office of Buddhist Affairs headed by Claremont College Professor Richard Gard. In 1966, Vietnamese monk and peace activist Thich Nhat Hanh came to the United States to speak about the conflict. His visit, coupled with the English publication of his book, Lotus in a Sea of Fire, so impressed Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. that King nominated Nhat Hanh for the Nobel Peace Prize.

1966 CE First Buddhist Monastery in Washington D.C.

The Washington Buddhist Vihara was the first Sri Lankan Buddhist temple in America. It was established in Washington, D.C. in 1966 as a missionary center with the support of the Sri Lankan government. The Ven. Bope Vinita Thera brought an image and a relic of the Buddha to the nation’s capital in 1965. The following year, the Vihara was incorporated, and in 1968, it moved to its present location on 16th Street, NW.

1969 CE Tibetan Center in Berkeley

Tarthang Tulku, a Tibetan monk educated at Banaras Hindu University in India, came to Berkeley and in 1969 established the Nyingma Meditation Center, the first Tibetan Buddhist center in the U.S.

1970 CE Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche to America

Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche was an Oxford-educated Tibetan teacher who brought the Karma Kagyu Tibetan Buddhist lineage to the U.S. in 1970. In 1971, he established Karma Dzong in Boulder, Colorado, and in 1973, he founded Vajradhatu, an organization consolidating many Dharmadhatu centers. Cutting through Spiritual Materialism, his classic introduction to Trungpa’s form of Tibetan Buddhism, was published in 1973.

1970 CE International Buddhist Meditation Center

The International Buddhist Meditation Center was established by Ven. Dr. Thich Thien-An, a Vietnamese Zen Master, in Los Angeles in 1970. The College of Buddhist Studies is also located on the grounds of the Center, which is currently under the direction of Thien-An’s student, Ven. Karuna Dharma.

1972 CE Korean Zen Master comes to Rhode Island

Korean Zen Master Seung Sahn came to the United States in 1972 with little money and little knowledge of English. He rented an apartment in Providence and worked as a washing machine repairman. A note on his door said simply, “What am I?” and announced meditation classes. Thus began the Providence Zen Center, followed soon by Korean Zen Centers in Cambridge, New Haven, New York, and Berkeley, all part of the Kwan Um School of Zen.

1974 CE Buddhist Chaplain in California

In 1974, the California State Senate appointed Rev. Shoko Masunaga as its first Buddhist and first Asian-American chaplain.

1974 CE First Buddhist Liberal Arts College

Naropa Institute was founded in Boulder, Colorado in 1974 as a Buddhist-inspired but non-sectarian liberal arts college. It aimed to combine contemplative studies with traditional Western scholastic and artistic disciplines. The accredited college now offers courses at the undergraduate and graduate levels in Buddhist studies, contemplative psychotherapy, environmental studies, poetics, and dance.

1974 CE Redress for Internment of Japanese Americans

In 1974, Rep. Phillip Burton of California addressed the U.S. House of Representatives on the topic “Seventy-five Years of American Buddhism” as part of an ongoing debate surrounding redress for Japanese Americans interned during World War II.

1975 CE The Fall of Saigon and the Arrival of Refugees

About 130,000 Vietnamese refugees, many of them Buddhists, came to the U.S. in 1975 after the fall of Saigon. By 1985 there were 643,200 Vietnamese in the U.S. Dr. Thich Thien-an, a Vietnamese monk and scholar already in Los Angeles, began the first Vietnamese Buddhist temple in America – the Chua Vietnam – in 1976. The temple is still thriving on Berendo Street, not far from central Los Angeles. With the end of the war, some 70,000 Laotian, 60,000 Hmong, and 10,000 Mien people also arrived in the U.S. as refugees bringing their religious traditions, including Buddhism, with them.

1976 CE Council of Thai Bhikkhus

The Council of Thai Bhikkhus, a nonprofit corporation founded in 1976 and based in Denver, Colorado, became the leading nationwide network for Thai Buddhism.

1976 CE City of 10,000 Buddhas

The City of 10,000 Buddhas was established in 1976 in Talmage, California by the Dharma Realm Buddhist Association as the first Chinese Buddhist monastery for both monks and nuns. The City of 10,000 Buddhas consists of sixty buildings, including elementary and secondary schools and a university, on a 237-acre site.

1976 CE First Rinzai Zen Monastery

On July 4 1976, Dai Bosatsu Zendo Kongo-ji, America’s first Rinzai Zen monastery, was established in Lew Beach, New York, under the direction of Eido Tai Shimano-roshi.

1979-1989 CE Cambodian Refugees Come to the U.S.

The regime of Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge ended in 1979 with the Vietnamese invasion of Cambodia. Over the following ten years, 180,000 Cambodian refugees were relocated from Thailand to the United States. In 1979, the Cambodian Buddhist Society was established in Silver Spring, Maryland, as the first Cambodian Buddhist temple in America. Later in 1987, the nearly 40,000 Cambodian residents of Long Beach, California, purchased the former headquarters of the Oil, Chemical and Atomic Workers Union and converted the huge building into a temple complex.

1980 CE First Burmese Temple

Dhammodaya Monastery, the first Burmese Buddhist temple in America, was established in Los Angeles in 1980.

1980 CE Buddhist Sangha Council

The Buddhist Sangha Council of Los Angeles (later of Southern California) was established under the leadership of the Ven. Havanpola Ratanasara in 1980. It was one of the first cross-cultural, inter-Buddhist organizations, bringing together monks and other leaders from a wide range of Buddhist traditions.

1986 CE Buddhist Astronaut on Challenger

Lt. Col. Ellison Onizuka, a Hawaiian-born Jodo Shinshu Buddhist, was killed 73 seconds after takeoff in the space shuttle Challenger in 1986. He was the first Asian-American to reach space.

1987 CE American Buddhists Get Organized

For ten days in July of 1987, Buddhists from all the Buddhist lineages in North America came together in Ann Arbor, Michigan, for a Conference on World Buddhism in North America — intended to promote dialogue, mutual understanding, and cooperation. In the same year, the Buddhist Council of the Midwest gathered twelve Chicago-area lineages of Buddhism; in Los Angeles, the American Buddhist Congress was created, with 47 Buddhist organizations attending its inaugural convention. Also in 1987, the Sri Lanka Sangha Council of North America was established in Los Angeles to serve as the national network for Sri Lankan Buddhism.

1987 CE Buddhist Books Gain Wider Audience

In 1987, Joseph Goldstein and Jack Kornfield published what became a classic book on vipassana meditation – Seeking the Heart of Wisdom: The Path of Insight Meditation. Thich Nhat Hanh, who was residing at Plum Village in France and visiting the United States annually, also published Being Peace, a classic treatment of “engaged Buddhism” – Buddhism that is concerned with social and ecological issues.

1990s CE Popular Buddhism

Throughout the 1990s, immigrant and American-born Buddhist communities were growing and building across the United States. In the midst of this flourishing, there emerged a popular “Hollywood Buddhism” or a Buddhism of celebrities which persists today. Espoused by figures from Tina Turner to the Beastie Boys to bell hooks, Buddhism became a larger part of mass culture during the 90s.

1991 CE Tricycle: the Buddhist Review

The first issue of Tricycle: the Buddhist Review, a non-sectarian national Buddhist magazine, was published in 1991. The journal features articles by prominent Buddhist teachers and writers as well as pieces on Buddhism and American culture at large.

1991 CE Tibetan Resettlement in the United States

The National Office of the Tibetan Resettlement Project was established in New York in 1991 after the U.S. Congress granted 1,000 special visas for Tibetans, all of them Buddhists. Two years later, the Tibetan Community Assistance Program opened to assist Tibetans resettling in New York. Cluster groups of Tibetan refugees have since established their own small temples and have begun to encounter Euro-American practitioners of Tibetan Buddhism.

1991 CE Dalai Lama in Madison Square Garden

For more than a week in October in 1991, the Dalai Lama gave the “Path of Compassion” teachings and conferred the Kalachakra Initiation in Madison Square Garden in New York City.

1993 CE Centennial of the World’s Parliament of Religions

There were many prominent Buddhist speakers at the 1993 Centennial of the World’s Parliament of Religions in Chicago, among them Thich Nhat Hanh, Master Seung Sahn, the Ven. Mahaghosananda, and the Ven. Dr. Havanpola Ratanasara. The Dalai Lama gave the closing address. There were myriad Buddhist co-sponsors of the event, including the American Buddhist Congress, Buddhist Churches of America, Buddhist Council of the Midwest, World Fellowship of Buddhists, and Wat Thai of Washington, D.C.

2006 CE American Monk Named First U.S. Representative to World Buddhist Supreme Conference

In 2006, Venerable Bhante Vimalaramsi (Sayadaw Gyi U Vimalaramsi Maha Thera) was nominated and confirmed as the first representative from the United States for the World Buddhist Supreme Conference, which is held every two years and includes representatives from fifty countries.

2007 CE First Buddhist Congresswoman Sworn In

Rep. Mazie Hirono, a Democrat from Hawaii, in 2007 became the first Buddhist to be sworn into the United States Congress.

Today, Buddhism thrives in America, with American Buddhists comprising myriad backgrounds, identities, and religious traditions and often integrating Buddhism with other forms of spiritual practice. It is estimated that there are roughly 3.5 million Buddhist practitioners in the United States at present. Many live in Hawaii or Southern California, but there are surely followers of Buddhism around the nation.

Selected Publications & Links

Takaki, Ronald . A Different Mirror . Boston: Little, Brown & Co. 1993.

Sidor, Ellen S . A Gathering of Spirit: Women Teaching in American Buddhism . Cumberland: Primary Point Press, 1987.

Tweed, Thomas A., and Stephen Prothero (eds.) . Asian Religions in America: A Documentary History . New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Access to Insight

America burma buddhist association, american buddhist congress, buddha’s light international association, buddhist churches of america, explore buddhism in greater boston.

Buddhism arrived in Boston in the 19th century with the first Chinese immigrants to the city and a growing intellectual interest in Buddhist arts and practice. Boston’s first Buddhist center was the Cambridge Buddhist Association (1957). The post-1965 immigration brought new immigrants into the city—from Cambodia and Vietnam, as well as Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Korea. These groups brought with them a variety of Buddhist traditions, now practiced at over 90 area Buddhist centers and temples. Representing nearly every ethnicity, age, and social strata, the Buddhist community of Greater Boston is a vibrant presence in the city.

- University Libraries

- Research Guides

- Themes & Issues

Buddhism: Themes & Issues

- General & Introductory

- Online Resources

- Theravada: Main

- Theravada: Primary Texts

- Theravada: Early & Indian Buddhism

- Theravada: Southeast Asia & Sri Lanka

- Theravada: Teachers & Teachings

- Mahayana: Main

- Mahayana: Primary Texts

- Mahayana: China, Mongolia, Taiwan

- Mahayana: Japan, Korea, Vietnam

- Mahayana: Major Thinkers

- Tibet: Main

- Tibet: Topics

- Tibet: Practices

- Tibet: Early Masters & Teachings

- Tibet: Contemporary Masters & Teachings

- Zen: Regions

- Zen: Early Masters & Teachings

- Zen: Contemporary Masters & Teachings

- Zen: The Kyoto School

- Western: Main

- Western: Thinkers & Topics

- Visual & Material Culture: Main

- Visual & Material Culture: Central Asia

- Visual & Material Culture: East Asia

- Visual & Material Culture: South Asia

- Visual & Material Culture: Southeast Asia & Sri Lanka

Buddhism as Philosophy: Fundamental Themes

Jeffery D. Long, Discovering Indian Philosophy: An Introduction to Hindu, Jain, and Buddhist Thought (2024)

Andy Karr, Into the Mirror: A Buddhist Journey through Mind, Matter, and the Nature of Reality (2023)

Tyler Dalton McNabb & Erik Daniel Baldwin, Classical Theism and Buddhism: Connecting Metaphysical and Ethical Systems (2023)

Zhihua Yao, Nonexistent Objects in Buddhist Philosophy: On Knowing What There Is Not (2023)

Haidy Geismar et al (eds.), Impermanence: Exploring Continuous Change Across Cultures (2022)

Roger R. Jackson, Rebirth: A Guide to Mind, Karma, and Cosmos in the Buddhist World (2022)

Harrison J. Pemberton, The Buddha Meets Socrates: A Philosopher's Journal (2022)

Rick Repetti (ed.), Routledge Handbook on the Philosophy of Meditation (2022)

Avram Alpert, A Partial Enlightenment: What Modern Literature and Buddhism Can Teach Us about Living Well without Perfection (2021)

Bhikkhu Analayo, Superiority Conceit in Buddhist Traditions: A Historical Perspective (2021)

Zane M. Diamond, Gautama Buddha: Education for Wisdom (2021)

C.W. Huntington, What I Don't Know about Death: Reflections on Buddhism and Mortality (2021)

Jianxun Shi, Mapping the Buddhist Path to Liberation: Diversity and Consistency Based on the Pali Nikayas and the Chinese Agamas (2021)

Mark Siderits, How Things Are: An Introduction to Buddhist Metaphysics (2021)

Peter D. Hershock & Roger T. Ames (eds.), Human Beings or Human Becomings? A Conversation with Confucianism on the Concept of Person (2021)

Y. Karunadasa, The Buddhist Analysis of Matter (2020)

Mark Siderits et al (ed.), Buddhist Philosophy of Consciousness: Tradition and Dialogue (2020)

Jan Westerhoff, The Non-Existence of the Real World (2020)

Graham Priest, The Fifth Corner of Four: An Essay on Buddhist Metaphysics and the Catuskoti (2019)

Vajragupta Staunton, Free Time! From Clock-Watching to Free-Flowing: A Buddhist Guide (2019)

David Burton, Buddhism: A Contemporary Philosophical Investigation (2017)

Steven M. Emmanuel (ed.), Buddhist Philosophy: A Comparative Approach (2017)

Bryan W. Van Norden, Taking Back Philosophy: A Multicultural Manifesto (2017)

Mark Siderits, Studies in Buddhist Philosophy, ed. Jan Westerhoff (2016)

Marcus Boon, Eric M. Cazdyn, & Timothy Morton, Nothing: Three Inquiries in Buddhism (2015)

Jay L. Garfield, Engaging Buddhism: Why It Matters to Philosophy (2015)

JeeLoo Liu & Douglas Berger (eds.), Nothingness in Asian Philosophy (2014)

Steven M. Emmanuel (ed.), A Companion to Buddhist Philosophy (2013)

Cyrus Panjvani, Buddhism: A Philosophical Approach (2013)

Mark Siderits, Evan Thompson, & Dan Zahavi (eds.), Self, No Self? Perspectives from Analytical, Phenomenological, and Indian Traditions (2013)

Robin Cooper (Ratnaprabha), Finding the Mind: A Buddhist View (2012)

John Danvers, Agents of Uncertainty: Mysticism, Scepticism, Buddhism, Art and Poetry (2012)

Louis de La Vallée Poussin, The Way to Nirvana: Six Lectures on Ancient Buddhism as a Discipline of Salvation (2012)

Musashi Tachikawa, Essays in Buddhist Theology (2012)

Johannes Bronkhorst, Karma (2011)

Alf Hiltebeitel, Dharma: Its Early History in Law, Religion, and Narrative (2011)

Dhivan Thomas Jones, This Being, That Becomes: The Buddha's Teaching on Conditionality (2011)

Erich Frauwallner, The Philosophy of Buddhism [Die Philosophie des Buddhismus], trans. Gelong Lodro Sangpo & Jigme Sheldron (2010)

Rodney Smith, Stepping Out of Self-Deception: The Buddha's Liberating Teaching of No-Self (2010)

William Edelglass & Jay Garfield (eds.), Buddhist Philosophy: Essential Readings (2009)

Dan Arnold, Buddhists, Brahmins, and Belief: Epistemology in South Asian Philosophy of Religion (2008)

George Grimm, Buddhist Wisdom: The Mystery of the Self (2008)

Stephen J. Laumakis, An Introduction to Buddhist Philosophy (2008)

Sangharakshita, The Meaning of Conversion in Buddhism (2008)

Dharmachari Subhuti, Buddhism and Friendship (2008)

Sangharakshita, The Buddha's Noble Eightfold Path (2007)

Mark Siderits, Buddhism as Philosophy: An Introduction (2007)

Lama Shenpen Hookham, There's More to Dying Than Death: A Buddhist Perspective (2006)

Bruce Matthews, Craving and Salvation: A Study in Buddhist Soteriology (2006)

Sangharakshita, The Three Jewels: The Central Ideals of Buddhism (2006)

Jennifer Crawford, Spiritually-Engaged Knowledge: The Attentive Heart (2005)

John Taber (ed. & trans.), A Hindu Critique of Buddhist Epistemology: Kumarila on Perception (2005)

Fernando Tola & Carmen Dragonetti, On Voidness: A Study of Buddhist Nihilism (2005)

David Burton, Buddhism, Knowledge and Liberation: A Philosophical Study (2004)

Richard H. Jones, Mysticism and Morality: A New Look at Old Questions (2004)

Maitreyabandhu, Thicker Than Blood: Friendship on the Buddhist Path (2004)

Nagapriya, Exploring Karma and Rebirth (2004)

Sangharakshita, Buddha Mind (2004)

Sangharakshita, Living with Kindness: The Buddha's Teaching on Metta (2004)

John W. Schroeder, Skillful Means: The Heart of Buddhist Compassion (2004)

Brook Ziporyn, Being and Ambiguity: Philosophical Experiments with Tiantai Buddhism (2004)

Christina Feldman, Compassion: Listening to the Cries of the World (2003)

Vincent L. Wimbush & Richard Valantasis (eds.), Asceticism (2002)

Rupert Gethin, The Buddhist Path to Awakening: A Study of the Bodhi-Pakkhiya Dhamma (2001)

David J. Kalupahana, Buddhist Thought and Ritual (2001)

Michael C. Brannigan, The Pulse of Wisdom: The Philosophies of India, China, and Japan (1999)

Duncan Forbes, The Buddhist Pilgrimage, ed. Alex Wayman (1999)

Roger R. Jackson & John J. Makransky (eds.), Buddhist Theology: Critical Reflections by Contemporary Buddhist Scholars (1999)

Jamie Hubbard & Paul L. Swanson (eds.), Pruning the Bodhi Tree: The Storm over Critical Buddhism (1997)

Alex Wayman, Untying the Knots in Buddhism: Selected Essays (1997)

Newman Robert Glass, Working Emptiness: Toward a Third Reading of Emptiness in Buddhism and Postmodern Thought (1995)

Kaisa Puhakka, Knowledge and Reality: A Comparative Study of Divine and Some Buddhist Logicians (1994)

Robert E. Buswell & Robert M. Gimello (eds.), Paths to Liberation: The Marga and Its Transformations in Buddhist Thought (1992)

Jan Nattier, Once upon a Future Time: Studies in a Buddhist Prophecy of Decline (1992)

John M. Koller & Patricia Koller (eds.), Sourcebook in Asian Philosophy (1991)

Gail Hinich Sutherland, The Disguises of the Demon: The Development of the Yaksa in Hinduism and Buddhism (1991)

Gregory Darling, An Evaluation of the Vedantic Critique of Buddhism (1987)

Martin Willson, Rebirth and the Western Buddhist (1987)

Alphonse Verdu, The Philosophy of Buddhism: A "Totalistic" Synthesis (1981)

John r. carter, dhamma: western academic and sinhalese buddhist interpretations: a study of a religious concept (1978).

W.H. Weeraratne, Individual and Society in Buddhism (1977)

David J. Kalupahana, Buddhist Philosophy: A Historical Analysis (1976)

William M. McGovern, A Manual of Buddhist Philosophy (1976)

David J. Kalupahana, Causality: The Central Philosophy of Buddhism (1975)

Francis Story, Rebirth as Doctrine and Experience: Essays and Case Studies (1975)

Junjiro Takakusu, Wing-Tsit Chan & Charles A. Moore (eds.), The Essentials of Buddhist Philosophy (1975)

John E. Blofeld, Beyond the Gods: Taoist and Buddhist Mysticism (1974)

Herbert V. Guenther, Buddhist Philosophy in Theory and Practice (1972)

Daigan L. Matsunaga & Alicia Matsunaga, The Buddhist Concept of Hell (1971)

Ven. nyanaponika & maurice walshe (eds.), pathways of buddhist thought: essays from the wheel (1971).

T. Stcherbatsky, The Central Conception of Buddhism and the Meaning of the Word "Dharma" (1961)

This book is a collection of essays by Mark Siderits on topics in Indian Buddhist philosophy. The essays are divided into six main systematic sections, dealing with realism and anti-realism, further problems in metaphysics and logic, philosophy of language, epistemology, ethics, and specific discussions of the interaction between Buddhist and classical Indian philosophy. Each of the essays is followed by a postscript Siderits has written specifically for this volume, which make it possible to connect essays of the volume with each other, showing thematic interrelations, or locating them relative to the development of Siderits’s thought. New works have been published, new translations have come out, and additional connections have been discovered. The postscripts make it possible to acquaint the reader with the most important of these developments.

This book is the most comprehensive single volume on the subject available. It offers the very latest scholarship to create a wide-ranging survey of the most important ideas, problems, and debates in the history of Buddhist philosophy. Encompasses the broadest treatment of Buddhist philosophy available, covering social and political thought, meditation, ecology and contemporary issues and applications Each section contains overviews and cutting-edge scholarship that expands readers understanding of the breadth and diversity of Buddhist thought. Broad coverage of topics allows flexibility to instructors in creating a syllabus. Essays provide valuable alternative philosophical perspectives on topics to those available in Western traditions.

This book examines how the Brahmanical tradition of Purva Mimamsa and the writings of the seventh-century Buddhist Madhyamika philosopher Candrakirti challenged dominant Indian Buddhist views of epistemology. Arnold retrieves these two very different but equally important voices of philosophical dissent, showing them to have developed highly sophisticated and cogent critiques of influential Buddhist epistemologists such as Dignaga and Dharmakirti. His analysis—developed in conversation with modern Western philosophers like William Alston and J.L. Austin—offers an innovative reinterpretation of the Indian philosophical tradition, while suggesting that pre-modern Indian thinkers have much to contribute to contemporary philosophical debates.

Buddhism is essentially a teaching about liberation - from suffering, ignorance, selfishness and continued rebirth. Knowledge of 'the way things really are' is thought by many Buddhists to be vital in bringing about this emancipation. This book is a philosophical study of the notion of liberating knowledge as it occurs in a range of Buddhist sources. Burton assesses the common Buddhist idea that knowledge of the three characteristics of existence (impermanence, not-self and suffering) is the key to liberation. It argues that this claim must be seen in the context of the Buddhist path and training as a whole. Detailed attention is also given to anti-realist, sceptical and mystical strands within the Buddhist tradition, all of which make distinctive claims about liberating knowledge.

Ecology, Economics, Globalization, and the Environment

Susan Bauer-Wu, A Future We Can Love: How We Can Reverse the Climate Crisis with the Power of Our Hearts & Minds (2023)

Susan Murphy, A Fire Runs Through All Things: Zen Koans for Facing the Climate Crisis (2023)

Trine Brox & Elizabeth Williams-Oerberg (eds.), Buddhism and Waste: The Excess, Discard and Afterlife of Buddhist Consumption (2022)

Daniel Capper, Buddhist Ecological Protection of Space: A Guide for Sustainable Off-Earth Travel (2022)

Jeanine M. Canty, Returning the Self to Nature: Undoing Our Collective Narcissism and Healing Our Planet (2022)

Daniel Capper, Roaming Free Like a Deer: Buddhism and the Natural World (2022)

David Hinton, Wild Mind, Wild Earth: Our Place in the Sixth Extinction (2022)

Joel Magnuson, The Dharma and Socially Engaged Buddhist Economics (2022)

Christoph Brumann et al (eds.), Monks, Money, and Morality: The Balancing Act of Contemporary Buddhism (2021)

Josep M. Coll, Buddhist and Taoist Systems Thinking: The Natural Path to Sustainable Transformation (2021)

Sallie B. King, Buddhist Visions of the Good Life for All (2021)

Gábor Kovács, The Value Orientations of Buddhist and Christian Entrepreneurs: A Comparative Perspective on Spirituality and Business Ethics (2021)

Shantigarbha, The Burning House: A Buddhist Response to the Climate and Ecological Emergency (2021)

Trine Brox & Elizabeth Williams-Oerberg, Buddhism and Business: Merit, Material Wealth, and Morality in the Global Market Economy (2020)

Alex John Catanese, Buddha in the Marketplace: The Commodification of Buddhist Objects in Tibet (2020)

Ernest C.H. Ng, Introduction to Buddhist Economics: The Relevance of Buddhist Values in Contemporary Economy and Society (2020)

Geoffrey Barstow (ed.), The Faults of Meat: Tibetan Buddhist Writings on Vegetarianism (2019)

Geoffrey Barstow, Food of Sinful Demons: Meat, Vegetarianism, and the Limits of Buddhism in Tibet (2019)

Candi K. Cann (ed.), Dying to Eat: Cross-Cultural Perspectives on Food, Death, and the Afterlife (2019)

Gergely Hidas, A Buddhist Ritual Manual on Agriculture: A Critical Edition (2019)

Stephanie Kaza, Green Buddhism: Practice and Compassionate Action in Uncertain Times (2019)

Belden C. Lane, The Great Conversation: Nature and the Care of the Soul (2019)

Clair Brown, Buddhist Economics: An Enlightened Approach to the Dismal Science (2018)

Shravasti Dhammika, Nature and the Environment in Early Buddhism (2018)

Karine Gagné, Caring for Glaciers: Land, Animals, and Humanity in the Himalayas (2018)

Willis J. Jenkins, Mary Evelyn Tucker, and John Grim (eds.), Routledge Handbook of Religion and Ecology (2018)

Vajragupta, Wild Awake: Alone, Offline and Aware in Nature (2018)

Whitney Bauman, Richard Bohannon, and Kevin O'Brien (eds.), Grounding Religion: A Field Guide to the Study of Religion and Ecology, 2nd ed. (2017)

Caroline Brazier, Ecotherapy in Practice: A Buddhist Model (2017)

J. Baird Callicott & James McRae (eds.), Japanese Environmental Philosophy (2017)

David E. Cooper & Simon P. James, Buddhism, Virtue and Environment (2017)

Simon P. James, Zen Buddhism and Environmental Ethics (2017)

Bodhipaksa, Vegetarianism: A Buddhist View (2016)

Padmasiri De Silva, Environmental Philosophy and Ethics in Buddhism (2016)

Todd LeVasseur et al (eds.), Religion and Sustainable Agriculture: World Spiritual Traditions and Food Ethics (2016)

Daniel P. Scheid, The Cosmic Common Good: Religious Grounds for Ecological Ethics (2016)

J. Baird Callicott & James McRae (eds.), Environmental Philosophy in Asian Traditions of Thought (2015)

Ugo Dessì, Japanese Religions and Globalization (2015)

Vaddhaka Linn, The Buddha on Wall Street: What's Wrong with Capitalism and What We Can Do About It (2015)

Joan Marques, Business and Buddhism (2015)

James Stewart, Vegetarianism and Animal Ethics in Contemporary Buddhism (2015)

Whitney A. Bauman, Religion and Ecology: Developing a Planetary Ethic (2014)

James Mark Shields (ed.), Buddhist Responses to Globalization (2014)

Susan M. Darlington, The Ordination of a Tree: The Thai Buddhist Environmental Movement (2013)

Tariq Jazeel, Sacred Modernity: Nature, Environment and the Postcolonial Geographies of Sri Lankan Nationhood (2013)

Bhikkhu Nyanasobhano, Landscapes of Wonder: Discovering Buddhist Dhamma in the World Around Us (2013)

Leslie E. Sponsel, Spiritual Ecology: A Quiet Revolution (2012)

Pragati Sahni, Environmental Ethics in Buddhism: A Virtues Approach (2011)

David M. Engel & Jaruwan S. Engel, Tort, Custom, and Karma: Globalization and Legal Consciousness in Thailand (2010)

Roger S. Gottlieb (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Religion and Ecology (2010)

Lin Jensen, Deep Down Things: The Earth in Celebration and Dismay (2010)

Richard Payne, How Much is Enough? Buddhism, Consumerism, and the Human Environment (2010)

Thomas Berry, The Sacred Universe: Earth, Spirituality, and Religion, ed. Mary Evelyn Tucker (2009)

Peter D. Hershock, Buddhism in the Public Sphere: Reorienting Global Interdependence (2009)

John Stanley et al (eds.), A Buddhist Response to the Climate Emergency (2009)

Ananda W. P. Guruge, Buddhism, Economics and Science: Further Studies in Socially Engaged Humanistic Buddhism (2008)