EDITORIAL article

Editorial: autism: innovations and future directions in psychological research.

- 1 Body, Eye and Movement Lab, Division of Neuroscience and Experimental Psychology, Faculty of Biology, Medicine and Health, Manchester Academic Health Science Centre, University of Manchester, Manchester, United Kingdom

- 2 Centre for Research in Autism and Education (CRAE), UCL Institute of Education, London, United Kingdom

- 3 Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Medical Faculty, LMU Munich, Munich, Germany

Editorial on the Research Topic Autism: Innovations and Future Directions in Psychological Research

Psychological research on autism has a long tradition, covering multiple fields including cognition, perception, clinical research, neuroscience, and social psychology. This Research Topic brings together the latest research in this area, mapping key developments, innovations, and future directions. In this editorial, we will discuss six themes that we have identified across the 22 contributions to this Research Topic: (1) Theories and mechanisms; (2) Characterization of autism; (3) Sensory experiences, perception and movement; (4) Language; (5) Support and interventions; and (6) Methods and technologies. We also provide thoughts on future directions in the field.

Theories and Mechanisms

Recent discussions have focused on the double-empathy theory (e.g., Milton, 2012 ; Bolis et al., 2017 ; but see Georgescu et al., 2020 ), which interprets communication “difficulties” associated with autism as a bidirectional breakdown between two interaction partners. Building on this theory, Crompton et al. conducted an innovative empirical study examining interpersonal rapport as a function of the neurology of interaction partners, and the person rating levels of rapport. When rating rapport after semi-structured conversations, homogeneous dyads of non-autistic people reported highest levels of rapport, followed by homogeneous dyads of autistic people and lastly mixed (autistic/non-autistic) dyads. Interestingly, taking an outside perspective, when rating observed rapport between interaction partners, homogeneous dyads of autistic individuals were rated highest concerning observed rapport, followed by homogeneous dyads of non-autistic individuals and lastly, again, mixed (autistic/non-autistic) dyads, supporting the double empathy theory.

Beyond specific aspects of functioning, Gernert et al. suggest that empirical and theoretical considerations should move toward a more comprehensive outlook on autism. The authors' Generalized Adaptation Account suggests potential connections between findings from genetics, neurobiology, endocrinology, cellular and neuronal connectivity levels. In this framework, aberrations of neurodevelopmental signaling pathways link up to alterations of neuronal connectivity with cascading effects on neuroendocrine dysregulations and impact on circadian functioning. Consequently, chronic distress and hyperactivation of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (HPA)-axis result in oxytocinergic downregulation linked to social functioning. This unifying account tries to capture both the complexity of presentation of autism and, in particular, its heterogeneity.

Characterization of Autism

Two articles in this Research Topic were concerned with better characterizing different aspects of autism. Li et al. used the Griffiths Mental Development Scales to characterize the cognitive, motor and social profiles of 398 autistic children (18–96 months old) in China. Findings suggested that many children showed an unbalanced profile (e.g., boys scored better than girls on eye-hand coordination, performance and practical reasoning; and differences in motor behavior became more pronounced with age). Significant aspects to take from this study were the characterization of autistic children in different regions of the world and the need to identify a child's strengths and challenges to develop personalized support.

Characterization can also be useful for predicting the future outcomes of autistic children. Forbes et al. predicted adult outcomes using an impressive dataset of participants who had been repeatedly assessed through childhood, adolescence and adulthood. Only verbal and non-verbal IQ, as well as daily living skills, could be confidently predicted from childhood data while prediction of other aspects (e.g., behavior, adult well-being, depression) was more difficult. Importantly, the authors discuss that views on what constitutes good adult outcomes for autistic children can vary. As acknowledged by the authors, this is clearly a challenging and evolving subject where stakeholder involvement is required.

Sensory Experiences, Perception and Movement

Awareness of the significance of sensory experiences and perceptual processing on the lives of autistic individuals has increased in recent years ( Torres and Donnellan, 2015 ; Autistica, 2016 ). In this Research Topic, we featured three perceptual studies that all employed rigorous, well-controlled methods to examine this topic. Mihaylova et al. used detailed psychophysical methods to progress understanding of mid-level visual processing in autistic children and adolescents. Results suggested that atypical global grouping (studied in a contour integration task), may be due to higher stimulus-dependent noise in the autistic group, leading to difficulties rejecting background noise and detecting the target.

The effect of low-mid level perceptual differences on higher level perceptual processes was elegantly shown across two studies by Lebreton et al. Here, the authors demonstrated how the commonly reported autistic preference for local compared to global detail impacted upon implicit (unconscious) and explicit (conscious) memory. This is a fascinating finding requiring replication, but has implications for understanding how perceptual style in both autistic and non-autistic individuals affects later memory recall.

Finally, Silver et al. examined whether the intense interests frequently observed in autistic individuals were related to visual processing changes for objects within that category. Contrary to expectations, there were no differences between autistic and non-autistic individuals in visual search abilities for images associated with intense interests. As such, despite enhanced time spent by autistic individuals gazing at images related to an interest, this did not seem to translate to a direct impact on visual processing ability. Linking back to Lebreton et al. , we wonder whether the degree of local-global bias in the participants may mediate any relationship between visual experience and visual search ability.

In another fascinating study featured in our Research Topic, Parmar et al. conducted qualitative work with a multidisciplinary team of Optometrists, autism researchers and autistic individuals, using focus groups to provide an in-depth understanding of visual sensory issues. As well as providing a rich description of sensory experiences, the researchers highlighted how visual issues had significant negative impacts on personal well-being and daily life, but also some positive aspects (e.g., detecting details that non-autistic individuals may overlook).

Another article in our Research Topic, by Buckle et al. , is the first to highlight Autistic Inertia—a debilitating difficulty of acting on intentions. The article was led by an autistic researcher (based on calls for research on this topic from autistic individuals) and the research highlighted how significant, and potentially common, Autistic Inertia is. Using qualitative methods, the study provided a detailed description of Inertia and the impact of it on autistic people's lives. Two particularly revealing findings were the benefit of other people in helping the individual to overcome being “stuck” and participants wanting to interact with others, but being unable to initiate interaction (which may be interpreted as a lack of social interest).

New approaches in the study of linguistic properties of autism were reported in this Research Topic. Marini et al. combined macrolinguistic (pragmatic, contextual processing) and microlinguistic (word and sentence processing) perspectives of language, which have traditionally been considered independently, showing that morphological and grammatical difficulties were related. Such findings suggest a relationship between difficulties in message planning and organization, which might impact children's grammatical production skills.

New avenues in language research were also highlighted by Sturrock et al. when considering potential gender differences in linguistic studies of autistic people. From a synthesis of previous literature, the authors concluded that there was a very specific profile of language and communication strengths and weaknesses for autistic females without intellectual disability, when compared to both autistic males and non-autistic females. The authors discuss how poorer recognition of autism in females might be influenced by female advantages in aspects of linguistic functioning (but see Lehnhardt et al., 2016 ).

In a further paper, Williams et al. demonstrated a new approach to studying communication differences between autistic and non-autistic people using relevance theory. This account posits that optimal communication is based on shared and mutually recognized relevance of utterances, which might be mismatched between autistic and non-autistic people when communicating due to differences in experiences of the world. This theoretical approach feeds into the discussions of double-empathy theory (see Theories and mechanisms).

Support and Interventions

Leadbitter et al. 's article proposes that early intervention research could and should be aligned with principles derived from autistic self-advocacy and the neurodiversity movement. Engagement with these principles would lead to, for example, intervention research focusing on changing environments (as opposed to changing autistic people), as well as intervention researchers respecting autistic developmental trajectories and priorities for intervention targets.

In line with this approach, Di Renzo et al. examined the interactions between autistic children and their parents during play, finding that parents who were more accepting of their children's autism diagnosis and who were better able to see things from their children's perspective, were more likely to be attuned with their children during play. Such work highlights the central role of parents as partners in supporting autistic children, and the importance of shared understanding between autistic people and their non-autistic communicative partners (see section Theories and Mechanisms).

Two further studies focused on the important role of parents. Papadopoulos et al. considered support and intervention for young disabled people, 41% of whom had a primary diagnosis of autism. The authors concluded that, to ensure that organized physical activities met the needs of young disabled people, there was a need for activities to be enjoyable, for the participation of siblings and parents to be promoted, and for low-income families to be supported to participate. This work again emphasizes that autism interventions can focus on changing the structures around young people, as opposed to changing the young people themselves.

Relatedly, Devenish et al. examined the effects of lower rates of community participation by autistic young people on their caregivers. Devenish et al. found that if caregivers perceived community supportiveness to be low, this predicted caregiver feelings of isolation. Findings were interpreted within a social model of disability, highlighting how autistic people are disabled by barriers in society.

Not all intervention studies featured in this Research Topic found positive effects of interventions (moving away from the publication bias that once dominated published intervention research). Brehm et al. conducted an initial evaluation of a training programme for parents of autistic children without intellectual/language impairments. The purpose of the evaluation was to evaluate how acceptable the training was for parents, and the results were positive with hardly any parents dropping out of the training programme. Yet a variety of primary outcome measures (e.g., quality of life, social communication) did not show significant improvement. Brehm et al. note that these findings can be useful for directing future work on such interventions.

Similarly, Saul and Norbury presented an alternative to Randomized Controlled Trials for research with rare/complex populations. Drawing on a research study with minimally verbal autistic children, the authors tested the efficacy of a parent-mediated app designed to support speech production, via Randomization Tests and Between Case Effect Sizes. As with Brehm et al.'s study, there was no significant effect of the intervention. Yet the research still made an important contribution to the literature; notably demonstrating the importance of robust experimental design and replicable approaches, as well as showing how it is possible to conduct rigorous intervention research with rare or complex samples.

It was also encouraging to see an example of a high-quality case study featured in the article by Courchesne et al. , which critically considered the role of interests and strengths in autism, particularly highlighting that these aspects do not necessarily link with academic potential. Courchesne et al. discussed an autistic teenager, C.A., who had above-average musical and calendar calculation abilities, along with pronounced difficulties in other areas (e.g., receptive and expressive language disorder). This discrepancy was found to lead to anxiety, frustration and some behavioral issues due to pressure to use his relative strengths to learn academic skills. Yet, an intervention package that focused on expectations, anxiety and emotional regulation through psychiatric intervention, parental coaching and psychotherapy, improved well-being and behavior. Courchesne et al. caution that while strengths and interests can lead to emotional well-being they should be seen as independent from adaptive outcomes such as academic achievement.

Methods and Technologies

A key message from studies in this theme is the need to develop and validate more ecologically valid assessments of autistic characteristics. For example, Morrison et al. administered standardized measures of social cognition, social skill, and social motivation to autistic and non-autistic adults, and assessed whether these predicted “real-world” social interaction outcomes (measured using unstructured conversations with unfamiliar social partners). While autistic adults scored lower than their non-autistic peers on the three standardized social tasks and were evaluated less favorably during the unstructured social interaction, the links between performance on the standardized measures and unstructured interaction were minimal. The authors therefore question the utility of traditional measures of social performance in autistic people, calling for more ecologically valid assessments.

In line with this approach, Schaller et al. used mobile eye-tracking glasses during autism diagnostic assessments to record gaze behavior of autistic and non-autistic children and adolescents. The authors focused on the percentage of time spent looking at different areas of interest of the face and body of the interviewer and the surrounding space. Significant group differences were found, with non-autistic participants appearing to process faces and facial expressions in a holistic way focusing on the central-face region, whereas autistic participants tended to avoid this face region. The authors stress that the results are preliminary and in need of replication, but this represents an exciting avenue for further work using an ecologically valid methodology.

Conclusions and Future Directions

Illuminating psychological science on autism from different thematic perspectives has shown several directions we can observe in the field of psychological research. For example: researchers taking a broader perspective, by incorporating previously distinct areas or methods into comprehensive studies; pairing quantitative analysis with qualitative appraisal of experience; putting forward unifying theories spanning different fields; examining an autistic person's strengths and challenges and tailoring more personalized support; developing alternative methods for evaluating interventions in more complex populations; and the implementation of a participatory approach to research. We would like to thank the contributors for their varied and stimulating contributions and hope that this Research Topic stimulates further cutting-edge psychological research that benefits the autistic community.

Author Contributions

EG drafted a first version of the Editorial. EG, LC, and CF-W wrote sections of the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We would particularly like to thank the authors and reviewers who contributed to this Research Topic for their valuable commitment to the field during such a trying time caused by the COVID pandemic.

Autistica (2016). Your Questions: Shaping Future Autism Research. Avalable online at: https://www.autistica.org.uk/downloads/files/Autism-Top-10-Your-Priorities-for-Autism-Research.pdf

Google Scholar

Bolis, D., Balsters, J., Wenderoth, N., Becchio, C., and Schilbach, L. (2017). Beyond Autism: introducing the dialectical misattunement hypothesis and a bayesian account of intersubjectivity. Psychopathology 50, 355–372. doi: 10.1159/000484353

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Georgescu, A. L., Koeroglu, S., Hamilton, A. F. C., Vogeley, K., Falter-Wagner, C. M., and Tschacher, W. (2020). Reduced nonverbal interpersonal synchrony in autism spectrum disorder independent of partner diagnosis: a motion energy study. Mol. Autism 11:11. doi: 10.1186/s13229-019-0305-1

Lehnhardt, F. G., Falter, C. M., Gawronski, A., Pfeiffer, K., Tepest, R., Franklin, J., et al. (2016). Sex-related cognitive profile in autism spectrum disorders diagnosed late in life: implications for the female autistic phenotype. J. Autism Dev. Disord . 46, 139-154. doi: 10.1007/s10803-015-2558-7

Milton, D (2012). On the ontological status of autism: the ‘double empathy problem'. Disabil. Soc. 27, 883–887. doi: 10.1080/09687599.2012.710008

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Torres, E. B., and Donnellan, A. M. (2015). Editorial for research topic “Autism: the movement perspective”. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 9, 1–5. doi: 10.3389/fnint.2015.00012

Keywords: autism, psychological research, cognition, perception, neuroscience, participatory research

Citation: Gowen E, Crane L and Falter-Wagner CM (2022) Editorial: Autism: Innovations and Future Directions in Psychological Research. Front. Psychol. 12:832008. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.832008

Received: 09 December 2021; Accepted: 22 December 2021; Published: 17 January 2022.

Edited and reviewed by: Irene Ceccato , University of Studies G. d'Annunzio Chieti and Pescara, Italy

Copyright © 2022 Gowen, Crane and Falter-Wagner. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Emma Gowen, emma.gowen@manchester.ac.uk

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

Autism spectrum disorders articles from across Nature Portfolio

Autism spectrum disorders are a group of neurodevelopmental disorders that are characterized by impaired social interaction and communication skills, and are often accompanied by other behavioural symptoms such as repetitive or stereotyped behaviour and abnormal sensory processing. Individual symptoms and cognitive functioning vary across the autism spectrum disorders.

Latest Research and Reviews

Behavioral mirroring in Wistar rats investigated through temporal pattern analysis

- Maurizio Casarrubea

- Jean-Baptiste Leca

- Giuseppe Crescimanno

Uncovering convergence and divergence between autism and schizophrenia using genomic tools and patients’ neurons

- Eva Romanovsky

- Ashwani Choudhary

- Shani Stern

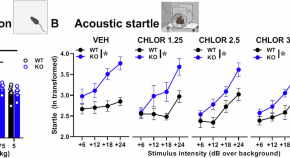

Therapeutic efficacy of the BKCa channel opener chlorzoxazone in a mouse model of Fragile X syndrome

- Celeste Ferraguto

- Marion Piquemal-Lagoueillat

- Susanna Pietropaolo

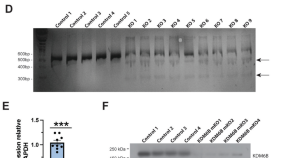

Impact of KDM6B mosaic brain knockout on synaptic function and behavior

- Bastian Brauer

- Carlos Ancatén-González

- Fernando J. Bustos

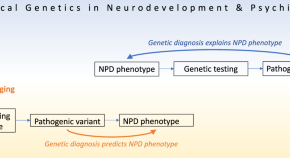

Integrative genetic analysis: cornerstone of precision psychiatry

- Jacob Vorstman

- Jonathan Sebat

- Sébastien Jacquemont

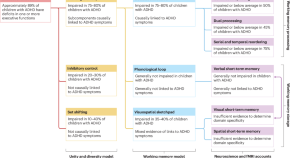

Executive function deficits in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and autism spectrum disorder

Children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and/or autism spectrum disorder show executive function deficits compared to neurotypical peers. In this Review, Kofler et al. question the evidence to examine whether these deficits are shared across both conditions and provide recommendations for future work.

- Michael J. Kofler

- Elia F. Soto

- Erica D. Musser

News and Comment

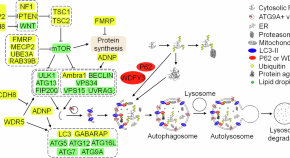

Impaired macroautophagy confers substantial risk for intellectual disability in children with autism spectrum disorders

- Audrey Yuen Chang

- Guomei Tang

Reorienting social communication research via double empathy

- Oluwatobi Abubakare

The exclusively inclusive landscape of autism research

People with intellectual disability are underrepresented and often actively excluded from autism research. A better understanding of autism requires inclusive research approaches that accurately represent the broad heterogeneity of the autistic population.

- Lauren Jenner

- Joanna Moss

Association of fluvoxamine with mortality and symptom resolution among inpatients with COVID-19

- Guangting Zeng

- Jianqiang Li

- Zanling Zhang

Autistic people three times more likely to develop Parkinson’s-like symptoms

Largest study of its kind also finds increased risk in older adults with a range of intellectual disabilities.

- Miryam Naddaf

Targeting RNA opens therapeutic avenues for Timothy syndrome

A therapeutic strategy that alters gene expression in a rare and severe neurodevelopmental condition has been tested in stem-cell-based models of the disease, and has been shown to correct genetic and cellular defects.

- Silvia Velasco

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Advances in autism research, 2021: continuing to decipher the secrets of autism

Affiliations.

- 1 State University of New York, Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, NY, USA. [email protected].

- 2 State University of New York, Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, NY, USA.

- PMID: 34045682

- DOI: 10.1038/s41380-021-01168-0

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- Genetic Studies in Autism. Sudarshan S, Gupta N, Kabra M. Sudarshan S, et al. Indian J Pediatr. 2016 Oct;83(10):1133-40. doi: 10.1007/s12098-015-1989-7. Epub 2016 Mar 3. Indian J Pediatr. 2016. PMID: 26935198

- Autism Spectrum Disorder is Mostly Due to Genetic Factors. Rosenberg K. Rosenberg K. Am J Nurs. 2019 Oct;119(10):56-57. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000586192.08336.1f. Am J Nurs. 2019. PMID: 31567257

- Advances in the identification and validation of autism biomarkers. Oakley BFM, Loth E, Jones EJH, Chatham CH, Murphy DG. Oakley BFM, et al. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2022 Oct;21(10):697-698. doi: 10.1038/d41573-022-00141-y. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2022. PMID: 36008547 No abstract available.

- Genetic Variation across Phenotypic Severity of Autism. Toma C. Toma C. Trends Genet. 2020 Apr;36(4):228-231. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2020.01.005. Epub 2020 Feb 6. Trends Genet. 2020. PMID: 32037010 Review.

- Autism in 2016: the need for answers. Posar A, Visconti P. Posar A, et al. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2017 Mar-Apr;93(2):111-119. doi: 10.1016/j.jped.2016.09.002. Epub 2016 Nov 9. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2017. PMID: 27837654 Review.

- Vincent JB, Konecki DS, Munstermann E, Bolton P, Poustka A, Poustka F, et al. Point mutation analysis of the FMR-1 gene in autism. Mol Psychiatry. 1996;1:227–31. - PubMed

- Licinio J, Alvarado II. Progress in the genetics of autism. Mol Psychiatry. 2002;7:229. - DOI

- Jamain S, Betancur C, Quach H, Philippe A, Fellous M, Giros B, et al. Linkage and association of the glutamate receptor 6 gene with autism. Mol Psychiatry. 2002;7:302–10. - DOI

- Kim SJ, Cox N, Courchesne R, Lord C, Corsello C, Akshoomoff N, et al. Transmission disequilibrium mapping at the serotonin transporter gene (SLC6A4) region in autistic disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2002;7:278–88. - DOI

- Bonora E, Bacchelli E, Levy ER, Blasi F, Marlow A, Monaco AP, et al. Mutation screening and imprinting analysis of four candidate genes for autism in the 7q32 region. Mol Psychiatry. 2002;7:289–301. - DOI

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

Grants and funding

- R21 MH126405/MH/NIMH NIH HHS/United States

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources.

- Nature Publishing Group

Other Literature Sources

- scite Smart Citations

- MedlinePlus Consumer Health Information

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

New Research May Change How We Think About the Autism Spectrum

Insar keynote suggests brain differences correlate with cognition—not diagnosis..

Posted May 16, 2022 | Reviewed by Davia Sills

- What Is Autism?

- Find a therapist to help with autism

- Dr. Evdokia Anagnostou presented the results of neuroimaging studies at the International Society for Autism Research 2022 annual meeting.

- Of note, brain differences clustered along dimensions of cognition and hyperactivity, not diagnosis.

- These findings suggest we need to reconsider how we classify neurodivergence.

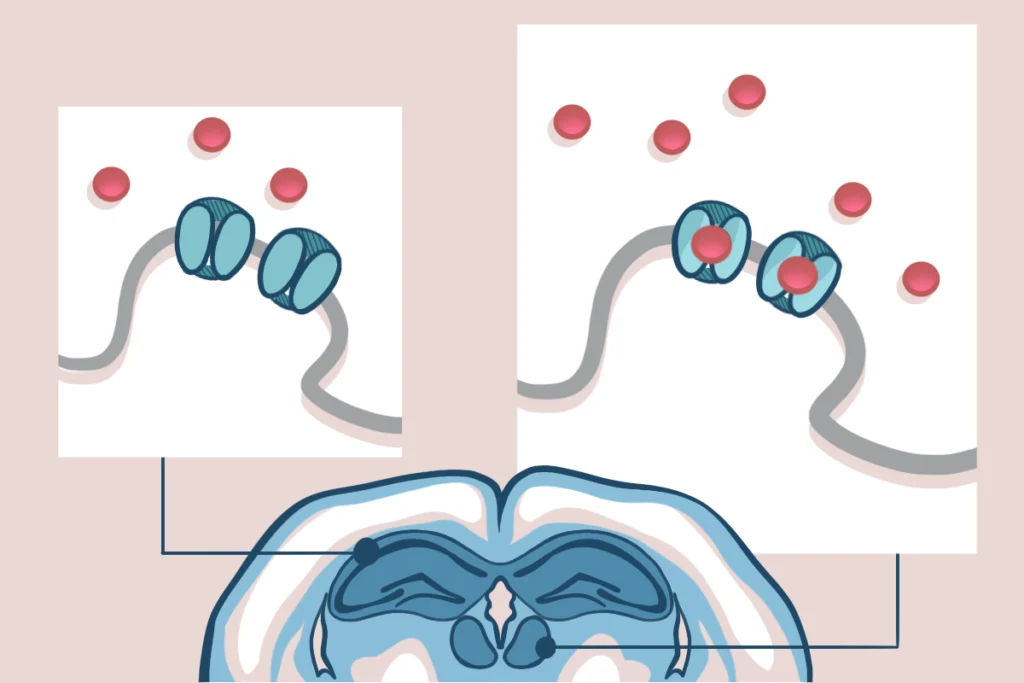

University of Toronto child neurologist Evdokia Anagnostou dropped a bombshell in her keynote Saturday at the annual meeting of the International Society of Autism Research (INSAR) in Austin, Texas, which may call into question the validity of the autism spectrum disorder (ASD) diagnosis.

What Brain Scans Tell Us About Autism Spectrum Disorder

Anagnostou and her colleagues had set out to use neuroimaging to identify brain differences unique to ASD, as compared to other neurodevelopmental differences like ADHD , OCD , and intellectual disability. And they did find that brain differences clustered into different groups—but not by diagnosis. In fact, brain scans could not distinguish children who had been diagnosed with ASD from those who had been diagnosed with ADHD or OCD.

“Dr. Anagnostou reported data from multiple papers that looked at over 3,500 children,” Dr. Alycia Halladay, Chief Science Officer at the Autism Science Foundation, explained to me. “These studies looked at multiple structural and functional features of the brain—including cortical gyrification (the way the brain folds in the cortex), connectivity of different brain regions, and the thickness of the cortical area—and found no differences based on diagnosis.”

Groupings did emerge, but they were along totally different axes. Added Halladay, “The brains themselves were more similar based on cognitive ability, hyperactivity, and adaptive behavior.” In other words, the brains of mildly affected autistic children looked much more like the brains of kids with ADHD than they did like those of severely autistic children.

Validity of the Autism Spectrum Diagnosis May Be at Stake

If replicated, these findings could have tremendous implications for our current diagnostic framework. During the question and answer period following her talk, Anagnostou described two children who both carried the diagnosis of autism; one was very mildly affected, while the other had such disordered behavior that “even their bus driver knows” he is autistic. “Should these kids have the same diagnosis?” she asked.

Right now, they do—but there has been a growing dissatisfaction among many stakeholders in the autism community with the American Psychiatric Association’s introduction of the all-encompassing ASD diagnosis in the 2013 revision of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-5) to replace more narrowly defined categories, including Asperger syndrome, pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS), and childhood disintegrative disorder.

In 2021, the Lancet Commission —a group of 32 researchers, clinicians, autistic individuals, and family members—called for the creation of a new label, “profound autism,” that would carve out those autistic individuals who also suffer from cognitive and language impairments and require round-the-clock supervision. “Anagnostou’s data converge nicely with the Lancet Commission’s proposal,” Halladay observed. “They provide biological evidence for a category that was originally defined solely by external criteria.”

At the very least. The real question is whether this work demands an even more radical re-imagining of our classification of neurodevelopmental differences. If, as Anagnostou’s data demonstrates, cognition and hyperactivity are much more correlated with brain difference than variables like social deficit that have been considered core symptoms of autism, then perhaps it’s time to scrap our current model and introduce new diagnoses based on these more salient dimensions. Aligning our diagnostic system with underlying biology is the first step in the development of targeted interventions for some of the most intractable and dangerous behaviors exhibited by the developmentally disabled, such as aggression , elopement, self-injury , and pica (the compulsion to eat inedible objects).

As Anagnostou opened her talk, “Nature doesn’t read the DSM.” But, as our understanding of the brain advances, shouldn’t the DSM reflect these divisions in nature?

Amy S.F. Lutz, Ph.D. , is a historian of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. She is the author of We Walk: Life with Severe Autism (2020) and Each Day I Like It Better: Autism, ECT, and the Treatment of Our Most Impaired Children (2014) . She is also the Vice-President of the National Council on Severe Autism (NCSA).

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

It’s increasingly common for someone to be diagnosed with a condition such as ADHD or autism as an adult. A diagnosis often brings relief, but it can also come with as many questions as answers.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

In updated U.S. autism bill, Congress calls for funding boost, expanded scope

The current Autism CARES Act sunsets in late September.

Listen to this story: Your browser doesn't support the audio element Back 15 seconds Play Pause Forward 15 seconds 0:00 / Spotify Apple Apple - opens a new tab Spotify Spotify Spotify - opens a new tab YouTube Youtube Youtube - opens a new tab Download Share on social media linkedin x twitter facebook Copy

Lawmakers are ironing out the next major tranche of federal funding for autism research in the United States, hoping to renew critical legislation before it expires on 30 September. The law—known as the Autism Collaboration, Accountability, Research, Education and Support (CARES) Act—has been in effect in some form since 2006 .

The latest slate of updates awaiting floor votes as soon as next week in the House and Senate includes renewing—and possibly expanding—the funding mandated for autism research, training and services. The House bill increases the current amount by $279 million, totaling a more than $2.1 billion investment over the next five years.

The latest Senate version proposes a slightly smaller jump, to $1.95 billion in spending over that same period. (Assuming both versions pass in their respective chambers, a conference committee will then finalize the act’s terms, subject to both House and Senate approval.) Both bills also contain a new provision requiring the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to develop an annual budget outlining how research dollars will be spent.

The funding upgrade proposed in each bill exceeds an inflation adjustment, says Thomas Frazier , professor of psychology at John Carroll University. It’s also notable in light of the sizable cuts facing other research programs , such as the BRAIN Initiative.

“In the context of a fixed or even diminishing federal budget, any increase is important,” says autism researcher M. Daniele Fallin , dean of public health at the Rollins School of Public Health at Emory University.

The revised act draws attention to several understudied areas, such as the dearth of effective communication tools for autistic people who are non- or minimally speaking. Both the House and Senate bills call for a new Autism Intervention Research Network focused on communication needs, a change that has sparked widespread support.

Even a small tweak in the law’s wording can affect research downstream, says Frazier, who also serves on the Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee (IACC), which the Autism CARES Act funds. “When we put language like this into the bill, we do see a shift in the funding agencies’ foci.”

Key among other proposed updates is language that paves the way for more inclusive autism research. The House bill, for example, directs federal agencies to support research that “reflects the entire population of individuals with autism spectrum disorder, including the full range of cognitive, communicative, behavioral, and adaptive functioning, as well as co-occurring conditions and needs for support and services.”

That wording addresses historical patterns of excluding from research autistic people who have intellectual disability or significant support needs. It also represents a “very careful compromise,” says Sam Crane , an independent disability advocacy consultant and a self-advocate member of IACC.

Some groups, including the Profound Autism Alliance and the Autism Science Foundation, had initially pushed for the law to specify “ profound autism ”—a label coined in 2021 to represent those who require round-the-clock care—among its priorities. But some people reject that term, citing, among other reasons, its inconsistent use. Following extended conversations with other organizations and members of Congress, supporters of the “profound autism” language changed course.

That phrasing, though, is not ideal, says Judith Ursitti , co-founder and president of the Profound Autism Alliance. “I’m not going to die on a hill about words,” she says, but the ambiguity could perpetuate the problem of omitting certain subgroups from research.

But incremental progress with this law is the norm, says Zoe Gross , director of advocacy at the Autistic Self Advocacy Network (ASAN). “We can’t call any CARES bill a complete victory,” she says. For example, although ASAN is glad to see the legislation include language surrounding communication needs, the organization did not achieve its ask for the bills to stipulate that half of IACC’s public members be autistic—a jump from the 2019 law’s requirement that at least three autistic people serve. ( One-third of the 21 current public members are autistic.)

Still, both bills manage to satisfy at least some of the requests of the major organizations in this space—many with disparate viewpoints, as Kim Musheno , executive vice president of public policy at the Autism Society of America, points out. “The hard sunset makes it serious that we really need to all be together on this,” she says.

Sign up for the weekly Spectrum newsletter to stay current with the latest advancements in autism research.

tags: Spectrum , Adults with autism , aging , Audio research news , Autism , Funding , Policy

Recommended reading

X-chromosome genes; neurobiology of infant crying; MCHAT in preemies

Task swap prompts data do-over for autism auditory perception study

Creating a more inclusive autism research community

Explore more from the transmitter.

Cell population in brainstem coordinates cough, new study shows

Ketamine targets lateral habenula, setting off cascade of antidepressant effects

From bench to bot: Does AI really make you a more efficient writer?

A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

A lock ( ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Signs and Symptoms

- Living with Autism Spectrum Disorder

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- Data and Statistics on Autism Spectrum Disorder

- Autism Materials and Resources

- Diagnosis ASD

- Information on ASD for Healthcare Providers

- Autism Acceptance Month Partner Toolkit

Related Topics:

- View All Home

- 2023 Community Report on Autism

- Autism Data Visualization Tool

Autism Spectrum Disorder Articles

At a glance.

Below is a list of recent scientific articles on autism spectrum disorder (ASD) generated from CDC programs and activities.

Key findings and scientific articles

Key findings.

These key findings provide brief summaries of some of CDC's latest ASD research.

Key Findings: ADDM Network Expands Surveillance to Identify Healthcare Needs and Transition Planning for Youth

Five of CDC's ADDM Network sites (Arkansas, Georgia, Maryland, Utah, and Wisconsin) began monitoring autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in 2018 among 16-year-old adolescents who were initially identified as having characteristics of ASD in 2010. (Published: February 25, 2023)

Key Findings: Study Shows Linking Statewide Data for ASD Prevalence is Effective

Linking statewide health and education data is an effective way for states to have actionable local ASD prevalence estimates when resources are limited. (Published: January 18, 2023)

Key Findings: CDC Releases First Estimates of the Number of Adults Living with Autism Spectrum Disorder in the United States

This study fills a gap in data on adults living with ASD in the United States because there is not an existing surveillance system to collect this information. (Published May 10, 2020)

CDC scientific articles

These articles are either from CDC-funded research or have at least one CDC author. These articles are listed by year of publication, with the most recent first.

- Adolescents With Autism Spectrum Disorder: Diagnostic Patterns, Co-occurring Conditions, and Transition Planning. Hughes MM, Shaw KA, Patrick ME, et al. J Adolesc Health. 2023;73(2):271-278.

- Statewide county-level autism spectrum disorder prevalence estimates—seven U.S. states, 2018. Shaw KA, Williams S, Hughes MM, et al. Ann Epidemiol. 2023;79:39-43.

- The Prevalence and Characteristics of Children With Profound Autism, 15 Sites, United States, 2000-2016. Hughes MM, Shaw KA, DiRienzo M, et al. Public Health Rep. 2023;138(6):971-980.

- Prevalence and Characteristics of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 8 Years—Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2020. Maenner MJ, Warren Z, Williams AR, et al. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2023;72(2):1-14. Published 2023 Mar 24. [ Easy-Read Summary ]

- Early Identification of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 4 Years—Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2020. Shaw KA, Bilder DA, McArthur D, et al. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2023;72(1):1-15. Published 2023 Mar 24. [ Easy-Read Summary ]

- Social vulnerability and prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder, Metropolitan Atlanta Developmental Disabilities Surveillance Program (MADDSP). Patrick ME, Hughes MM, Ali A, Shaw KA, Maenner MJ. Ann Epidemiol. 2023;83:47-53.e1.

- Individualized Education Programs and Transition Planning for Adolescents With Autism. Hughes MM, Kirby AV, Davis J, et al. Pediatrics. 2023;152(1):e2022060199. [ Watch Video Abstract ]

" There is no epidemic of autism. It's an epidemic of need."

Two authors provide their commentary on CDC's 2023 Community Report in an article published in ST A T News' First Opinion (March 2023).

Read the full article here.

- Toileting Resistance Among Preschool-Age Children With and Without Autism Spectrum Disorder. Wiggins LD, Nadler C, Hepburn S, Rosenberg S, Reynolds A, Zubler J. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2022;43(4):216-223.

- Defining in Detail and Evaluating Reliability of DSM-5 Criteria for Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) Among Children Rice CE, Carpenter LA, Morrier MJ, et al. J Autism Dev Disord. 2022;52(12):5308-5320. [published correction appears in J Autism Dev Disord. 2022 Jan 29;:].

- Reasons for participation in a child development study: Are cases with developmental diagnoses different from controls? Bradley CB, Tapia AL, DiGuiseppi CG, et al. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2022;36(3):435-445.

- Features that best define the heterogeneity and homogeneity of autism in preschool-age children: A multisite case–control analysis replicated across two independent samples. Wiggins LD, Tian LH, Rubenstein E, et al. Autism Res. 2022;15(3):539-550.

- Progress and Disparities in Early Identification of Autism Spectrum Disorder: Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 2002–2016. Shaw KA, McArthur D, Hughes MM, et al. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2022;61(7):905-914.

- Peri-Pregnancy Cannabis Use and Autism Spectrum Disorder in the Offspring: Findings from the Study to Explore Early Development. DiGuiseppi C, Crume T, Van Dyke J, et al. J Autism Dev Disord. 2022;52(11):5064-5071.

- Heterogeneity in Autism Spectrum Disorder Case-Finding Algorithms in United States Health Administrative Database Analyses. Grosse SD, Nichols P, Nyarko K, Maenner M, Danielson ML, Shea L. J Autism Dev Disord. 2022;52(9):4150-4163.

- Early identification of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 4 years—Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 sites, United States, 2018. Shaw KA, Maenner MJ, Bakian AV, et al. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2021;70(10):1-14. Published 2021 Dec 3.

- Prevalence and characteristics of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years—autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2018. Maenner MJ, Shaw KA, Bakian AV, et al. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2021;70(11):1-16. Published 2021 Dec 3.

- Comparison of 2 Case Definitions for Ascertaining the Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among 8-Year-Old Children. Maenner MJ, Graves SJ, Peacock G, Honein MA, Boyle CA, Dietz PM. Am J Epidemiol. 2021;190(10):2198-2207.

- Healthcare Costs of Pediatric Autism Spectrum Disorder in the United States, 2003–2015. Zuvekas SH, Grosse SD, Lavelle TA, Maenner MJ, Dietz P, Ji X. J Autism Dev Disord. 2021;51(8):2950-2958.

- Association between pica and gastrointestinal symptoms in preschoolers with and without autism spectrum disorder: Study to Explore Early Development. Fields VL, Soke GN, Reynolds A, et al. Disabil Health J. 2021;14(3):101052.

- Health Status and Health Care Use Among Adolescents Identified With and Without Autism in Early Childhood—Four US Sites, 2018–2020. Powell PS, Pazol K, Wiggins LD, et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(17):605-611. Published 2021 Apr 30.

- Evaluation of sex differences in preschool children with and without autism spectrum disorder enrolled in the study to explore early development. Wiggins LD, Rubenstein E, Windham G, et al. Res Dev Disabil. 2021;112:103897.

- A Distinct Three-Factor Structure of Restricted and Repetitive Behaviors in an Epidemiologically Sound Sample of Preschool-Age Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Hiruma L, Pretzel RE, Tapia AL, et al. J Autism Dev Disord. 2021;51(10):3456-3468.

- Spending on Young Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder in Employer-Sponsored Plans, 2011–2017 Grosse SD, Ji X, Nichols P, Zuvekas SH, Rice CE, Yeargin-Allsopp M. Psychiatr Serv. 2021;72(1):16-22. [published correction appears in Psychiatr Serv. 2021 Jan 1;72(1):97].

- A Preliminary Epidemiology Study of Social (Pragmatic) Communication Disorder Relative to Autism Spectrum Disorder and Developmental Disability Without Social Communication Deficits. Ellis Weismer S, Rubenstein E, Wiggins L, Durkin MS. J Autism Dev Disord. 2021;51(8):2686-2696.

- CE: From the CDC: Understanding Autism Spectrum Disorder. Christensen D, Zubler J. Am J Nurs. 2020;120(10):30-37.

- Early Identification of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aaged 4 Years—Early Autism and Developmental Disability Monitoring Network, Six Sites, United States, 2016. Shaw KA, Maenner MJ, Baio J, et al. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2020;69(3):1-11. Published 2020 Mar 27.

- Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 8 Years—Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2016. Maenner MJ, Shaw KA, Baio J, et al. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2020;69(4):1-12. Published 2020 Mar 27. [published correction appears in MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020 Apr 24;69(16):503].

- Disparities in Documented Diagnoses of Autism Spectrum Disorder Based on Demographic, Individual, and Service Factors. Wiggins LD, Durkin M, Esler A, et al. Autism Res. 2020;13(3):464-473.

SEED Research

Researchers working on CDC's Study to Explore Early Development (SEED) have published many studies reporting on important findings related to ASD.

For more information on the methods and descriptions of the SEED study sample, SEED publications, and the evaluation of clinical and laboratory methods using SEED data, click the link below.

Featured Article | Summer 2023

Cdc seed study explores prenatal ultrasound use and risk of autism spectrum disorder.

Prenatal ultrasound use and risk of autism spectrum disorder: Findings from the case-control Study to Explore Early Development (SEED). Christensen D, Pazol K, Overwyk KJ, et al. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2023;37(6):527-535.

Study findings

Many additional studies are underway. We will provide summaries of those studies in the future.

All articles

Search CDC Stacks for articles that have been published by CDC authors within the National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities from 1990 to present.

Feature articles and an Easy-Read Summary

Easy-Read Summary

Additional resources

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a developmental disability that can cause significant social, communication and behavioral challenges. CDC is committed to continuing to provide essential data on ASD and develop resources that help identify children with ASD as early as possible.

For Everyone

Health care providers, public health.

- Get Press Releases

- Media Contacts

- News Releases

- Photos & B-Roll Downloads

- VUMC Facts and Figures

- Credo Award

- DAISY Award

- Elevate Team Award

- Health, Yes

- Employee Spotlight

- Five Pillar Leader Award

- Patient Spotlight

- Pets of VUMC

- Tales of VUMC Past

- All Voice Stories

Explore by Highlight

- Community & Giving

- Education & Training

- Growth & Finance

- Leadership Perspectives

- VUMC People

Explore by Topic

- Emergency & Trauma

- Genetics & Genomics

- Health Equity

- Health Policy

- Tech & Health

- Women's Health

Explore by Location

- Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt

- Vanderbilt Bedford County Hospital

- Vanderbilt Health One Hundred Oaks

- Vanderbilt Health Affiliated Network

- Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center

- Vanderbilt Kennedy Center

- Vanderbilt Psychiatric Hospital

- Vanderbilt Wilson County Hospital

- Vanderbilt Stallworth Rehabilitation Hospital

- Vanderbilt Tullahoma-Harton Hospital

- Vanderbilt University Hospital

- Photos & B-Roll Downloads

Featured Story

Emergency & Trauma

The lifeflight legacy: 40 years in 40 photos, july 29, 2024, study sheds new light on autism, but there’s more work to be done.

A target of their investigations is serotonin, a signaling molecule that is well known for its critical roles in regulating mood and which also plays an important role in the development of the brain and nervous system.

Researchers from Columbia and Vanderbilt universities, the University of Illinois Chicago and colleagues across the country are making steady progress in their decades-long quest to understand autism spectrum disorder (ASD), a brain development condition that affects social interaction, communication and behavior.

In a recent study, the researchers measured blood levels of serotonin in women whose children were diagnosed with ASD. Some of the children carried rare genetic variations that strongly contribute to the risk of autism, while others did not.

In their paper, published July 4 in the Journal of Clinical Investigation , the researchers reported that higher serotonin levels were primarily found in women whose children who did not carry the rare variants.

This finding suggests that elevated maternal serotonin levels are associated with autism in a subset of children who have multiple common genetic or environmental factors which likely contribute to risk. Elevated levels are not found as frequently when a single, rare genetic variant explains most of the risk.

The link between autism-associated genetic variations and maternal serotonin levels was first described more than 60 years ago.

But it is a complicated picture that is not fully understood, noted James Sutcliffe , PhD, a pioneer in autism genetics at Vanderbilt University.

The study probed genetic samples from the University of Illinois Chicago (UIC) Autism Center of Excellence and from the UIC and Vanderbilt sites of the Simons Simplex Collection , a repository of samples from 2,600 families of children with ASD maintained by the Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative.

The study did not have a control group — it did not compare maternal serotonin levels to those from women whose children do not have autism. Another limitation was that serotonin blood levels in the women were measured after their children had been diagnosed with ASD.

Taking measurements throughout pregnancy would provide a more complete picture of how maternal serotonin levels may relate to autism risk, said Jeremy Veenstra-VanderWeele , MD, the Ruane Professor of Psychiatry and director of the Division of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry at Columbia University Irving Medical Center in New York City.

Veenstra-VanderWeele is corresponding author of the paper. Before coming to Columbia in 2014, he directed the Division of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at Vanderbilt University Medical Center and was medical director of the Treatment and Research Institute for Autism Spectrum Disorders ( TRIAD ) at the Vanderbilt Kennedy Center.

Sutcliffe, who co-authored the paper, is associate professor of Molecular Physiology & Biophysics and of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences at Vanderbilt.

Other co-authors are Edwin Cook , MD, also a pioneer in autism genetics who directs the Center for Neurodevelopmental Disorders and the Division of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at UI Health, and colleagues from New York University and Yale University School of Medicine.

While the true nature of the relationship between serotonin levels and ASD remains elusive, clinical trials are underway at Vanderbilt and elsewhere to evaluate drugs that, by impacting the serotonin system, may relieve irritability or improve social functioning in children with autism.

Genetic studies also have led to the identification of other, possibly related health conditions in children with ASD, including previously undiagnosed cardiac abnormalities and severe epilepsy that occurs during sleep, Sutcliffe said.

The investigators hope that further research may lead to targeted interventions based upon ASD-associated genetic variation or biomarkers. That, Veenstra-Vanderweele said, would be “transformative” for children who are severely affected by autism.

Related Articles

January 28, 2016

Autism study links sensory difficulties, serotonin system.

Vanderbilt researchers have established a link between the neurotransmitter serotonin and certain behaviors of some children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), a link that may lead to new treatments for ASD.

By VUMC News and Communications

January 9, 2014

Brain-gut connection in autism.

An association between rigid-compulsive behaviors and gastrointestinal symptoms in autism spectrum disorder may point to a common biological pathway that impacts both the brain and the gut.

By Leigh MacMillan

November 16, 2017

Study may point to new treatment approach for asd.

Using sophisticated genome mining and gene manipulation techniques, researchers at Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC) have solved a mystery that could lead to a new treatment approach for autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

By Bill Snyder

- Alzheimer's disease & dementia

- Arthritis & Rheumatism

- Attention deficit disorders

- Autism spectrum disorders

- Biomedical technology

- Diseases, Conditions, Syndromes

- Endocrinology & Metabolism

- Gastroenterology

- Gerontology & Geriatrics

- Health informatics

- Inflammatory disorders

- Medical economics

- Medical research

- Medications

- Neuroscience

- Obstetrics & gynaecology

- Oncology & Cancer

- Ophthalmology

- Overweight & Obesity

- Parkinson's & Movement disorders

- Psychology & Psychiatry

- Radiology & Imaging

- Sleep disorders

- Sports medicine & Kinesiology

- Vaccination

- Breast cancer

- Cardiovascular disease

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Colon cancer

- Coronary artery disease

- Heart attack

- Heart disease

- High blood pressure

- Kidney disease

- Lung cancer

- Multiple sclerosis

- Myocardial infarction

- Ovarian cancer

- Post traumatic stress disorder

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Schizophrenia

- Skin cancer

- Type 2 diabetes

- Full List »

share this!

April 16, 2021

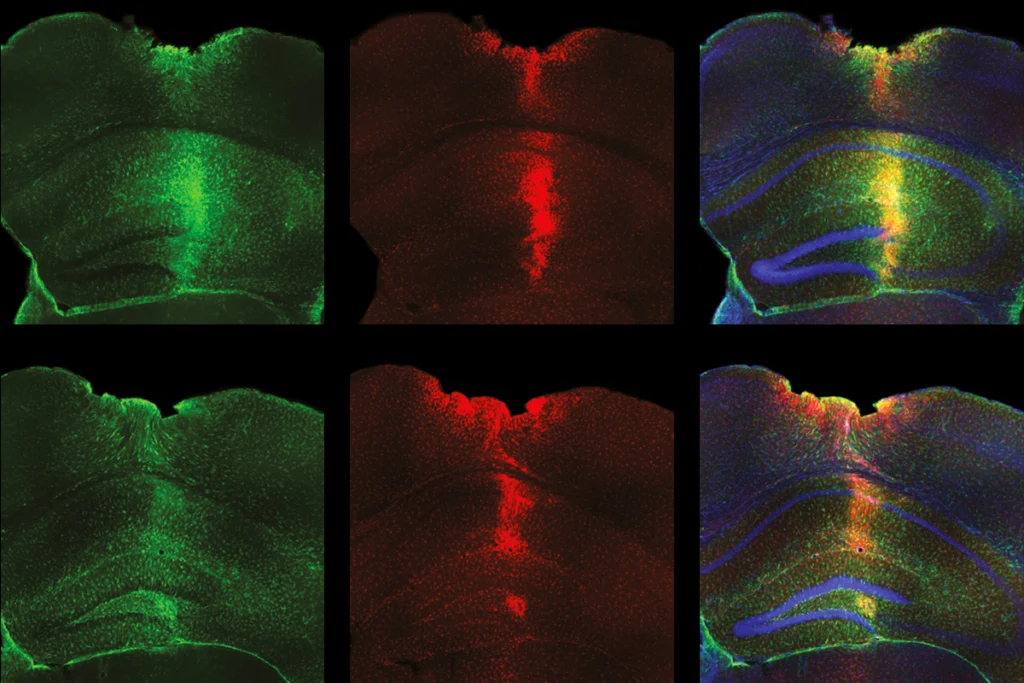

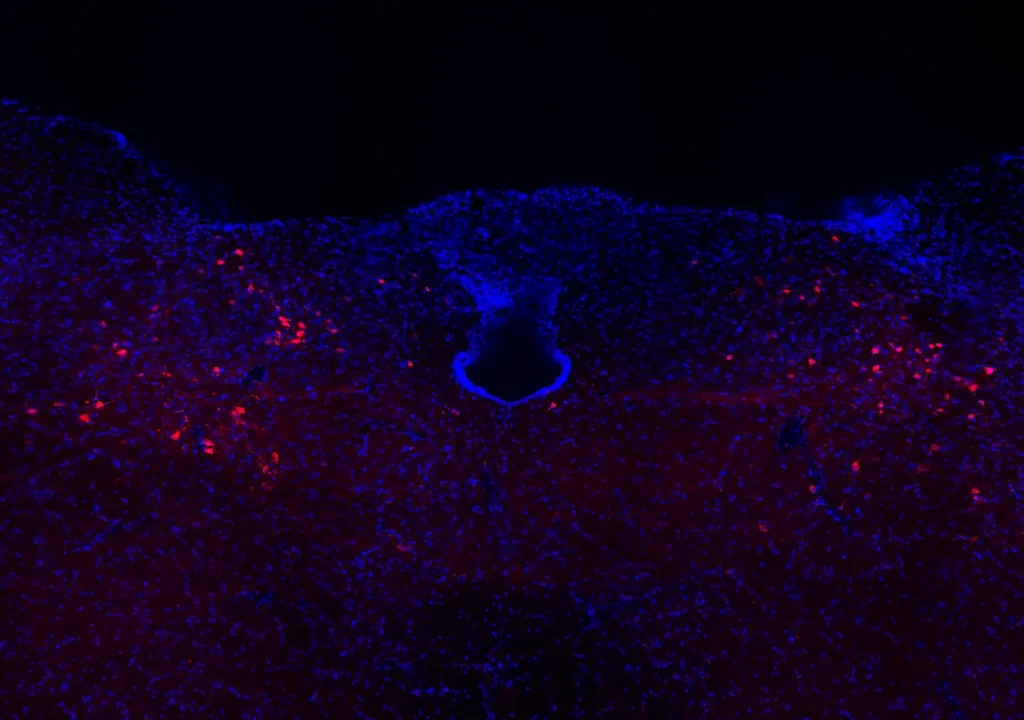

Autism develops differently in girls than boys, new research suggests

by University of Virginia

New research has shed light on how autism-spectrum disorder (ASD) manifests in the brains of girls, prompting the scientists to warn that conclusions drawn from studies conducted primarily in boys should not be assumed to hold true for girls.

The researchers discovered that there is a significant difference in the genes and 'genetic burden' that underpin the condition in girls and boys. They also identified specific ways the brains of girls with ASD respond differently to social cues such as facial expressions and gestures than do those of girls without ASD.

"This new study provides us with a roadmap for understanding how to better match current and future evidenced-based interventions to underlying brain and genetic profiles, so that we can get the right treatment to the right individual," said lead investigator Kevin Pelphrey, Ph.D., a top autism expert at the University of Virginia School of Medicine and UVA's Brain Institute. "This advances our understanding of autism broadly by revealing that there may well be different causes for boys vs. girls; this helps us understanding the heterogeneity within and across genders."

Understanding Autism-Spectrum Disorder

The new insights come from a sweeping research project, led by Pelphrey at UVA, that brings together expertise from Yale; Harvard; University of California, Los Angeles; Children's National; University of Colorado, Denver; and Seattle Children's. At UVA, key players included both Pelphrey, of the School of Medicine's Department of Neurology and the Curry School of Education and Human Development, and John D. Van Horn, Ph.D., of the School of Data Science and UVA's Department of Psychology.

The research combined cutting-edge brain imaging with genetic research to better understand ASD's effects in girls. Those effects have remained poorly explored because the condition is four times more common in boys.

Pelphrey and colleagues used functional magnetic-resonance imaging (fMRI) to examine brain activity during social interactions. They found that autistic girls used different sections of their brains than girls who did not have ASD. And, most surprisingly, the difference between girls with and without autism was not the same as the difference in the brain seen when comparing boys with and without autism, revealing different brain mechanisms at play in autism depending on a person's gender.

Likewise, the underlying genetic contributors were quite different, the researchers found. Girls had much larger numbers of rare variants of genes active during the early development of a brain region known as the striatum. This suggests that the effects on the striatum may contribute to ASD risk in girls. (Scientists believe a section of the striatum called the putamen is involved in interpreting both social interaction and language.)

"The convergence of the brain imaging and genetic data provides us with an important new insight into the causes of autism in girls," Pelphrey said. "We hope that by working with our colleagues in UVA's Supporting Transformative Autism Research (STAR), we will be able to leverage our findings to generate new treatment strategies tailored to autistic girls."

Explore further

Feedback to editors

Low-impact yoga and exercise found to help older women manage urinary incontinence

20 hours ago

Missouri patient tests positive for bird flu despite no known exposure to animals

Falling for financial scams? It may signal early Alzheimer's disease

Sep 6, 2024

Cognitive behavioral therapy enhances brain circuits to relieve depression

New molecular sensor enables fluorescence imaging for assessing sarcoma severity

Noninvasive focused ultrasound show potential for combating chronic pain

Study finds TGF-beta and RAS signaling are both required for lung cancer metastasis

Research team successfully maps the brain-spinal cord connection in humans

Alzheimer's study reveals critical differences in memory loss progression based on the presence of specific proteins

Chemical screen identifies PRMT5 as therapeutic target for paclitaxel-resistant triple-negative breast cancer

Related stories.

Girls are better at masking autism than boys

Apr 3, 2017

Research finds differences in the brains and behavior of girls and boys with autism

May 12, 2015

New study shows boys will be boys—sex differences aren't specific to autism

Jun 9, 2015

Girls and boys with autism differ in behavior, brain structure

Sep 3, 2015

Girls and boys on autism spectrum tell stories differently, could explain 'missed diagnosis' in girls

Apr 23, 2019

Girls' social camouflage skills may delay or prevent autism diagnosis

Jan 4, 2018

Recommended for you

Natural probiotic discovered in microbiomes of UK newborns

Nature vs. nurture: Depression amplified in difficult environments for youth with a larger left hippocampus, study finds

Sep 5, 2024

Neurological symptoms are common—and similar—in severely ill children with different conditions, finds study

Sep 4, 2024

Most states have increasing child, adolescent firearm mortality rates, study finds

Banning friendships can backfire: Moms who 'meddle' make bad behavior worse

Adolescent glioma subtype responds to CDK4/6 inhibitor

Let us know if there is a problem with our content.

Use this form if you have come across a typo, inaccuracy or would like to send an edit request for the content on this page. For general inquiries, please use our contact form . For general feedback, use the public comments section below (please adhere to guidelines ).

Please select the most appropriate category to facilitate processing of your request

Thank you for taking time to provide your feedback to the editors.

Your feedback is important to us. However, we do not guarantee individual replies due to the high volume of messages.

E-mail the story

Your email address is used only to let the recipient know who sent the email. Neither your address nor the recipient's address will be used for any other purpose. The information you enter will appear in your e-mail message and is not retained by Medical Xpress in any form.

Newsletter sign up

Get weekly and/or daily updates delivered to your inbox. You can unsubscribe at any time and we'll never share your details to third parties.

More information Privacy policy

Donate and enjoy an ad-free experience

We keep our content available to everyone. Consider supporting Science X's mission by getting a premium account.

E-mail newsletter

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Content Analysis of Abstracts Published in Autism Journals in 2021: The year in Review

Haris memisevic.

Faculty of Educational Sciences, University of Sarajevo, 71000, Sarajevo, Bosnia-Herzegovina

Amina Djipa

Ever since Leo Kanner first described autism in 1943, the research in this field has grown immensely. In 2021 alone, 5837 SCOPUS indexed documents were published with a title that contained the words: “autism”, “autistic”, or “ASD”. The purpose of this study was to examine the most common topics of autism research in 2021 and present a geographical contribution to this research.

We performed a content analysis of 1102 abstracts from the articles published in 11 Autism journals in 2021. The following journals, indexed by the SCOPUS database, were included: Autism, Autism Research, Molecular Autism, Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, Advances in Autism, Autism and Developmental Language Impairments , and Autism in Adulthood.

According to the analysis, the main research topics were: mental health, social communication, social skills, quality of life, parenting stress, ADHD, Covid-19, self-efficacy, special education, and theory of mind. In relation to geographic distribution, most studies came from the USA, followed by the UK, Australia, and Canada.

Research topics were aligned with the priorities set by stakeholders in autism, most notably persons with autism themselves and their family members. There is a big gap in research production between developed countries and developing countries.

Introduction

According to the 5th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders , Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by deficits in social communication and the pattern of stereotypical and repetitive behaviors (American Psychiatric Association, 2013 ). An Austrian-American psychiatrist Leo Kanner was the first scientist who described a condition that we now refer to as ASD in 1943 (Kanner, 1943 ). Ever since that seminal paper describing the case histories of 11 children was published, the interest in autism research has grown immensely. This is not surprising given the high prevalence of the condition. Current estimates show that ASD is a common disorder, with a median prevalence of around 1%, and a median male-to-female ratio of 4.2:1 (Zeidan et al., 2022 ). The rise in the prevalence of autism has been associated with new research and investments in autism research internationally (Pellicano et al., 2014 ). Given this rise in research funds dedicated to autism research, it is of critical importance to determine the research priorities in this field. In a study examining research priorities, stakeholders preferred applied to basic research topics and gave importance to topics such as co-occurring conditions, health and well-being, and lifespan issues (Frazier et al., 2018 ). From the parents’ perspective, the priorities are quite similar, and involve topics such as health and well-being, socialization and social support, community awareness, and understanding of Autism (Clark & Adams, 2020 ). Another topic of interest is the similarities and differences of the impact of autism in different world regions, as it is difficult to draw public attention to this condition in less developed countries (Hahler & Elsabbagh, 2015 ).

Thus, in this article, we examined the most frequent research topics in autism research in 2021 and reviewed from which countries these studies originate. The reference for this research is the SCOPUS database. The SCOPUS is an abstract and indexing database produced by Elsevier and covers abstracts and citations from 1966 to the present (Burnham, 2006 ). The SCOPUS database was selected for this analysis as it has broader coverage in the field of Social Sciences and Humanities than the Web of Science (Memisevic et al., 2019 ).

According to the SCOPUS database, in 2021, 5837 documents were published that in its title contained the words “autism”, autistic” or “ASD”. Most of these documents were scientific articles (5034), with the rest of the documents including books, chapters, and conference papers. As an illustration of this growth in autism research, let us point to the fact that in 2001 there were 558 such documents, and in 2011, there were 2120 documents. More than 100 scientific journals had at least five articles published in 2021 with the terms “autism”, “autistic”, or “ASD” in their titles. Most of the articles were from the fields of medicine, psychology, neuroscience, social sciences, biochemistry, and health professions, but also some less expected fields such as engineering, environmental science, physics, business, and agriculture.

This review aimed to analyze the most prevalent research topics in Autism journals indexed in SCOPUS in the year 2021. We also provided a brief overview of the ten most frequent research topics and additional information on articles dealing with these topics. Lastly, we wanted to examine the main contributing countries to autism research.

The SCOPUS scientific base was used to extract data for this study. We examined all journals indexed by SCOPUS whose titles had the word “autism”. There were 11 such journals: Autism, Autism Research, Molecular Autism, Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, Advances in Autism, Autism and Developmental Language Impairments, and Autism in Adulthood.

Procedure and Analysis

The inclusion criteria for this review were that the final version of the article was published in 2021, and that it was a research article including original scientific articles, brief reports, case studies, case reports, and review articles. We did not extract data from Editorials, Commentaries, Letters to Editor, Book Reviews, and Corrections. We extracted the following information for each article: (1) Journal’s name, (2) Title of the article, (3) Country of the corresponding author, and (4) Abstract. Total number of analyzed articles was 1102. From the analysis output, we created two categories. The first is related to research topic (theme). Phrases containing two or more words were extracted, and we manually selected meaningful research topics. The second category was related to the subjects (participants) of the studies. The data were analyzed with R computer program (R Core Team, 2021 ). In addition, we extracted information regarding the country of origin of the corresponding author as a proxy for geographical contribution to autism research.

We first present the number of abstracts retrieved from each of the journals.

As can be seen from Table 1 ., almost 1/3 (68.3%) of all articles were retrieved from the top three journals: Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, Autism Research, and Autism .

The number of abstracts of articles retrieved from Autism Journals

| Journal’ name | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| 364 | 33.0 | |

| 201 | 18.2 | |

| 188 | 17.1 | |

| 117 | 10.6 | |

| 64 | 6.0 | |

| 36 | 3.2 | |

| 32 | 2.9 | |

| 32 | 2.9 | |

| 26 | 2.3 | |

| 21 | 1.9 | |

| 21 | 1.9 |

The most common research topics in Autism Journals are presented in Table 2 .

The 15 most common research topics in Autism Journals

| Research topic | Count |

|---|---|

| 221 | |

| 92 | |

| 90 | |

| 67 | |

| 59 | |

| 56 | |

| 52 | |

| 51 | |

| 47 | |

| 46 | |

| 46 | |

| 46 | |

| 42 | |

| 41 | |

| 39 |

As can be seen from Table 2 . Mental health was the topic most frequently explored in these articles. Another category that we explored in relation to these abstracts was “participants”.

These data are shown in Table 3 .

Frequency of terms related to the category “participants”

| Subjects in the study | Count |

|---|---|

| 1908 | |

| 995 | |

| 717 | |

| 707 | |

| 673 | |

| 390 | |

| 294 | |

| 274 | |

| 243 | |

| 236 |

Finally, we examined the corresponding author’s countries to see the geographical contribution to autism research. We only presented data for countries that had 10 or more articles published out of 1102 reviewed articles (Table 4 ).

Corresponding author’s country

| Country | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| USA | 490 | 0.445 |

| UK | 144 | 0.131 |

| Australia | 88 | 0.080 |

| Canada | 61 | 0.055 |

| China | 39 | 0.035 |

| Israel | 23 | 0.021 |

| France | 19 | 0.017 |

| Italy | 18 | 0.016 |

| Spain | 18 | 0.016 |

| The Netherlands | 18 | 0.016 |

| Belgium | 16 | 0.015 |

| Japan | 16 | 0.015 |

| Turkey | 16 | 0.015 |

| Taiwan | 15 | 0.014 |

| Sweden | 12 | 0.011 |

| Germany | 10 | 0.009 |

By large margin, the USA had the largest share in autism research, followed by the UK, Australia, Canada, and China. There were total of 47 countries that contributed to the entire pool of studies, but the contribution of most of them was rather small. Actually, 32 countries had a contribution of less than 1%. Developing countries were largely underrepresented in the list of contributing countries.

The goal of the present study was to review the most common research topics that were published in Autism journals in 2021. The most frequent topic was mental health . This is not surprising given the challenges that people with ASD are facing with, as well as their families in their everyday lives. The Covid-19 pandemic probably caused an additional incentive for researching this topic. Several factors during the pandemic, such as lockdowns, physical distancing, economic breakdowns, all increase the risk of mental health problems and can even deepen health inequalities (Moreno et al., 2020 ). Given that people with ASD have much higher risk of co-occurring mental health conditions than those without ASD (Rydzewska et al., 2018 ), research interest in mental health deserves to be on the top of priorities in autism research. In line with this, there is a need to create and validate assessment instruments designed specifically for autistic individuals. One such promising instrument is the Assessment of Concerning Behavior which has very good psychometric properties and can be used in future studies (Tarver et al., 2021 ). Mental health was also explored in relation to job prospects of autistic individuals. Thus, mental health issues need to be addressed as they appear to negatively impact job search and maintenance (Martin & Lanovaz, 2021 ). Besides targeting people with autism, research in mental health also dealt with parents of autistic individuals. The research showed that parental mental health could be significantly improved through support services and by strengthening personal relationships (Schiller et al., 2021 ).

A topic that attracted much scientific attention was social communication, which is one of the core features of ASD. When exploring the abstracts containing the phrase “social communication” we discovered that in many abstracts this was not the main topic of the study but just part in which the authors defined and described autism. However, some of the studies dealt with social communication per se. For example, one study explored how social communication is related to early spoken language and how it predicts later language skills (Blume et al., 2021 ). Also, social communication was the subject of neuroanatomical studies. In one such study, authors examined neural synchronization of tempoparietal junction and found that participants with autism showed decreased neural synchrony of that brain region (Quiñones-Camacho et al., 2021 ). Lastly, let us mention an interesting study of yoga, in which authors indicated that creative yoga intervention might be a promising tool for improving social communication in children with ASD (Kaur et al., 2021 ).