- Open access

- Published: 02 March 2023

Reflection on the teaching of student-centred formative assessment in medical curricula: an investigation from the perspective of medical students

- Tianjiao Ma 1 , 4 ,

- Hua Yuan 1 ,

- Feng Li 1 ,

- Shujuan Yang 2 ,

- Yongzhi Zhan 2 ,

- Jiannan Yao 1 &

- Dongmei Mu 3

BMC Medical Education volume 23 , Article number: 141 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

3028 Accesses

3 Citations

7 Altmetric

Metrics details

Formative assessment (FA) is becoming increasingly common in higher education, although the teaching practice of student-centred FA in medical curricula is still very limited. In addition, there is a lack of theoretical and pedagogical practice studies observing FA from medical students’ perspectives. The aim of this study is to explore and understand ways to improve student-centred FA, and to provide a practical framework for the future construction of an FA index system in medical curricula.

This study used questionnaire data from undergraduate students in clinical medicine, preventive medicine, radiology, and nursing at a comprehensive university in China. The feelings of medical students upon receiving student-centred FA, assessment of faculty feedback, and satisfaction were analysed descriptively.

Of the 924 medical students surveyed, 37.1% had a general understanding of FA, 94.2% believed that the subject of teaching assessment was the teacher, 59% believed that teacher feedback on learning tasks was effective, and 36.3% received teacher feedback on learning tasks within one week. In addition, student satisfaction results show that students’ satisfaction with teacher feedback was 1.71 ± 0.747 points, and their satisfaction with learning tasks was 1.83 ± 0.826 points.

Students as participants and collaborators in FA provide valid feedback for improving student-centred FA in terms of student cognition, empowered participation, and humanism. In addition, we suggest that medical educators avoid taking student satisfaction as a single indicator for measuring student-centred FA and to try to build an assessment index system of FA, to highlight the advantages of FA in medical curricula.

Peer Review reports

During the COVID-19 pandemic, teaching models, assessments and feedback mechanisms in medical curricula were forced to adapt and make changes to minimize the negative impact of the epidemic on medical education [ 1 , 2 ]. Although online curricula during the epidemic led to a greater diversity of content [ 3 , 4 , 5 ], medical curricula have strong professional characteristics. They not only spread medical knowledge, but also cultivate the logical thinking ability of medical students to find, analyse and solve problems. This makes the teaching assessment face many challenges [ 6 , 7 ], a reduction in effective communication between students and faculty [ 8 ], a lack of depth and breadth in teaching models [ 9 , 10 ], and a repetition of assessment components such as attendance, group reporting, and answering questions during face-to-face instruction [ 11 ]. Therefore, a new issue in the development of modern medical education is that medical educators focus on students, pay attention to their real feelings and feedback, encourage their participation in teaching assessment, and continuously improve teaching models and assessment methods [ 12 , 13 ].

Student-centred includes a conceptual framework of three dimensions, namely cognitive (focus on student learning progress), agency (focus on student empowerment), and humanist (knowing students as individuals) [ 14 , 15 ], which guided the design of this study. In student-centred teaching assessment design, cognition was reflected in the educator’s focus on student learning performance [ 16 ]; agency required the educator to consider how to enhance student engagement through power sharing [ 17 ]; and humanism is integrated throughout the teaching and learning process [ 17 , 18 ], with the educator taking the initiative to understand students’ interests, desires, and needs. In other words, student-centred “power sharing” and “responsiveness to needs” are not separate, and teachers do not change their dominant position, but rather emphasize student agency, focusing on students’ learning experiences and meeting needs [ 14 ]. A recent student-centred study shows less attention to power sharing in East Asia than in other parts of the world [ 19 ], reminding us that student-centred teaching assessment needs to be validated in practice in a broader cultural educational context.

Formative assessment (FA) refers to the assessment in teachers and students systematically obtain evidence of students’ learning in the teaching process, promote students’ understanding of learning objectives, and support students to become learners and achieve learning objectives [ 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 ]. Teachers help students to establish a sense of ownership, continuously improve their own learning through teaching assessment, realize the value [ 24 ], and achieve assessment for learning. Modern medical education reform advocates for educators and researchers to support the realization of medical education goals, understanding and improving teaching assessment design [ 25 , 26 ]. Although the assessment of medical curricula is mainly summative [ 27 ], focusing on students’ memory of knowledge, the purpose of FA is to focus on students, not only focusing on students’ scores, but also personal feedback and skills [ 28 ], especially the mastery of knowledge and skills. The assessment itself is used for learning and application to learning. FA is widely used in medical teaching practice and research, but not all assessments are effective. Effective FA feedback needs to consider how students participate and how teachers help students make effective feedback [ 29 , 30 ].

Student satisfaction refers to the “subjective experience” of students in education and the perceived value of the learning experience [ 31 , 32 ]. Guided by the concept of student-centred humanism, educators are particularly concerned about student satisfaction, and student satisfaction has been recognized as a valid indicator of instructional assessment in both theoretical and practical studies of teaching and learning [ 32 ]. Some studies have shown that improvement of teaching activities by teachers directly affects on student satisfaction [ 33 ]. However, well-designed teaching assessments may not obtain higher student satisfaction [ 34 , 35 ]. This suggests a need for student-centred formative assessment and a deeper understanding of the value and role of student satisfaction, which has become a concern in medical education reform. We expect to understand medical students’ satisfaction after receiving student-centred FA and target the areas where FA needs to be changed. The quality of FA can be improved through scientific, appropriate, valid, and reliable methods [ 35 ]. At the same time, medical educators can benefit from feedback on students’ satisfaction and provide more appropriate teaching programs for independent learning [ 36 ].

Hence, this study selects medical students from a comprehensive university in China that has carried out medical curricula reform to observe and reflect on the content, methods, and feedback of teaching and learning assessments in medical curriculum through student-centred FA teaching practices. Based on the feedback regarding student satisfaction, we will also explore the shortcomings of FA as an indicator of student satisfaction and provide the best theoretical and practical framework for the design and implementation of FA in medicine or other disciplines.

Formative assessment design of medical curricula

The FA of medical curricula in a comprehensive university in China follows the principle of “teaching-assessment-feedback”. Starting from the feedback on teaching objectives, it investigates students’ views on the implementation of FA, matches with knowledge objectives, ability objectives and emotional value objectives, analyses whether the teaching objectives have been achieved, and teachers immediately give feedback their opinions to students. FA methods include topic discussion, classroom questions, and answers, classroom tests, reflection logs, mind maps, etc., focusing on quantification. Each assessment module has a different emphasis on the training of medical students’ knowledge and ability. Evaluators’ assessment methods include: mutual assessment between teachers and students, mutual assessment between students and students, and self-assessment by students and teacher assessment. The total score of each medical course is generally composed of the weighted and cumulative scores of each module of formative assessment, plus the final exam scores. Based on clinical medicine, FA has been extended horizontally to nursing, public health and preventive medicine and other specialties. It extends vertically from undergraduate education to postgraduate education.

In addition, the medical curriculum reform of this comprehensive university is student-centered, exploring the construction of a scientific and feasible FA index system, effectively evaluating teaching evaluation practices, and guiding teachers to cultivate students’ ability to reflect and learn independently. Therefore, from the perspective of students’ understanding, attitude and satisfaction to FA, enriching FA index system is worth discussing extensively.

Participants

The study was designed as an investigative study. This comprehensive university in China have School of Clinical Medicine, School of Public Health, and School of Nursing. The undergraduate majors include clinical medicine, preventive medicine, radiology, and nursing. According to the research purpose, the research team has set the inclusion criteria for research objects, as follows: (1) undergraduate students receiving medical education, (2) undergraduate students who understand the research purpose; (3) undergraduate students who were voluntary to participate. Undergraduate students who did not receive medical course education, as well as undergraduate students who are conducting clinical practice, are excluded. The research team learned about the curriculum plan for the autumn semester of the academic year 2021–2022 in advance, and selected undergraduates majoring in clinical medicine, preventive medicine, radiology, and nursing from October 2021 to December 2021 in a comprehensive university in China for investigation.

The research team contacted instructors of medical curricula who distributed questionnaires in class through an online questionnaire platform (Questionnaire Star), and members of the research team answered the questions raised by the students when filling in the questionnaire. The completion of the questionnaire was voluntary for the students and informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the college where the research team leading member was based (Ethics Committee Approval Number: 2020092104).

Questionnaire

The compilation of the questionnaire takes the student-centred conceptual framework of three dimensions as the theoretical basis of the research. In combination with the implementation background of FA in China’s medical education [ 15 , 37 ], the questions designed are mainly divided into four parts: the basic demographic information of the respondents (gender, grade and major), medical students’ cognition of FA (degree of understanding, assessment scoring rules, main persons who completed the assessment, etc.), feedback (the effectiveness and timeliness of teachers’ feedback), satisfaction (FA method, content, tools informationization, scoring criteria, teacher feedback, and learning tasks). Among them, the satisfaction survey was scored with Likert’s five point scale, 1 to 5 was: very satisfied, satisfied, fair, dissatisfied or very dissatisfied. For the questionnaire in this study, Cronbach’s α = 0.976, KMO = 0.982, significance level P < 0.001, indicating the reliability and validity of the questionnaire are good. The questionnaire is listed in the Supporting materials 1.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 26.0, and all statistical tests were two-sided, with P < 0.05 considered statistically significant. Data descriptions of medical students’ demographic information, medical students’ cognition of FA, feedback were expressed as frequencies and percentages. The results of student satisfaction were analysed and expressed as Mean ± Standard Deviation. For the word frequency in the answer text of the open question, Excel was used to make a word cloud to analysis.

Participant characteristics

In our study, there were 984 questionnaires distributed, 924 valid questionnaires were collected, and the efficiency was 93.9%. Of the 924 participants, 290 were male (31.4%), 634 were female (68.6%), fresh man was 302 (32.7%), sophomore was 295 (31.9%), junior was 210 (22.7%) and senior was 117 (12.7%). Clinical medicine 238 (25.8%), preventive medicine 240 (26.0%), radiation medicine 200 (21.6%) and nursing 246 (26.6%).

Medical students’ cognition of formative assessment

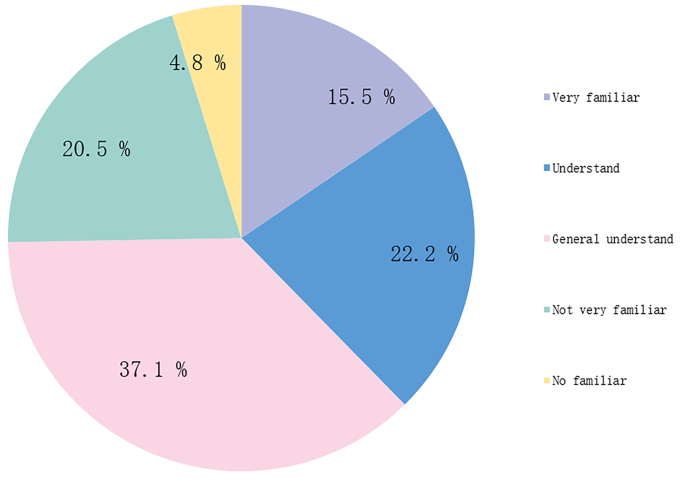

Students’ understanding of FA may help them participate in FA design, implementation and feedback. Before in-depth investigation, it is necessary to know the medical students’ understanding of FA. We through the question “How much do you know about formative assessment?”, preliminary understanding of medical students’ understanding of FA. Among the surveyed students, there were 143 (15.5%) very familiar, 205 (22.2%) understood, 343 (37.1%) general understood, 189 (20.5%) not very familiar, and 44 (4.8%) no familiar. (Fig. 1 and Supplemental Table 1 ).

The degree of understanding of formative assessment by students

Students’ understanding of the scoring method of formative assessment

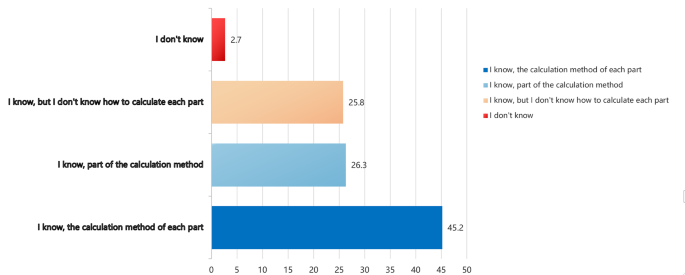

The content of FA is diverse, and the scoring method and weight of each method are different. In the survey of students, the question was “Do you know how to calculate the scores of each module of formative assessment?” They said they knew the calculation method of scores and the scores of each part, accounting for only 45.2% (Fig. 2 and Supplemental Table 2 ).

Medical students’ assessment of formative assessment teachers’ feedback

The effective feedback of FA considers the participation of students and how teachers can help students provide effective feedback. When students receive teacher assessment tasks, they undertake these tasks to achieve learning. The timing of teacher feedback is essential for students to acquire knowledge, which is helpful in improving the efficiency of FA. In our research, the feedback survey of medical students on FA of teachers shows that 59.0% think “I get effective feedback”. From the timeliness of feedback, the number of medical students who received feedback from teachers was 335 (36.3%) within one week, 275 (29.8%) immediately, 112 (12.1%) at the end of the course, 98 (10.6%) the second day, 52 (5.6%) within one month and 52 (5.6%) no feedback (Table 1 ).

The subjects of FA are usually teachers and students, the objects of assessment may be teachers, students’ learning process, teachers’ teaching quality and students’ learning quality. In the multiple choice question “Who do you think is the subject of FA?“, the options we set include teacher, student, peer and group. According to the survey results, 94.2% (870/924) thought it was the teacher, 45.1% (417/924) thought it was the student, 34.4% (318/924) thought it was peer, and 30.0% (277/924) thought it was a group (Fig. 3 and Supplemental Table 3 ).

Students’ views on the main implementers of formative assessment

Modules that medical students hope to add to the formative assessment of medical curricula

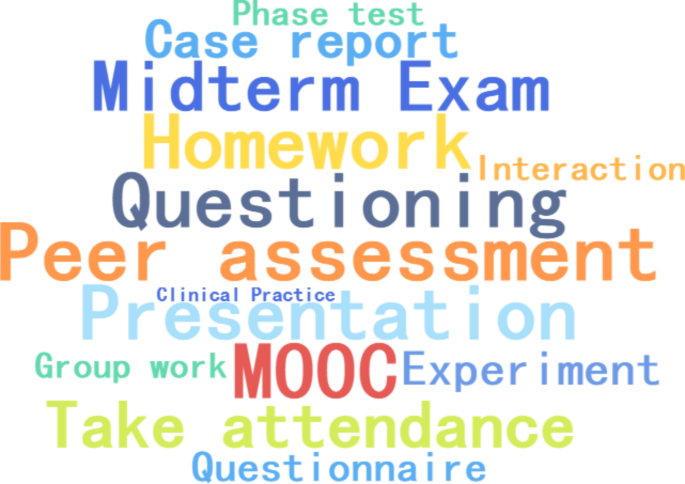

Open question “What formative assessment modules do you want to add in the future courses?“, The answer text is made into a word cloud, showing that the FA modules added by medical students in the future mainly include: peer assessment, presentation, questioning, take attendance, MOOC, etc. (Fig. 4 and Supplemental Table 4 ).

Formative assessment method preferred by medical students

Note: The font size indicates the module frequency that medical students want to increase in formative assessment, the higher the frequency, the larger the font.

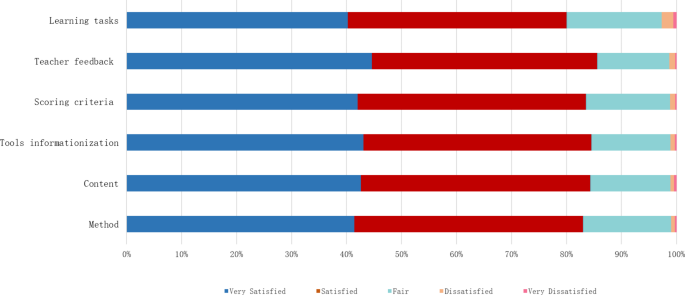

Satisfaction of medical students with the formative assessment of medical curricula

The results of medical students’ satisfaction with various items of FA can reflect students’ acceptance of FA. The higher the satisfaction of medical students, they may have better learning effect. When they have better learning effect, they will also have higher degree of satisfaction, so as to achieve the purpose of FA implementation. The satisfaction of medical students reflects the implementation effect of FA in terms of FA method, content, tools informationization, scoring criteria, teacher feedback, and learning tasks. In the investigation, we found that more than 40% of the students think they are very satisfied with the method, content, tools informationization, scoring criteria, teacher feedback, and learning tasks in medical curricula FA, the results of student satisfaction show that students’ satisfaction with teacher feedback was 1.71 ± 0.747 points. Their satisfaction with learning tasks was 1.83 ± 0.826 points (Table 2 ; Fig. 5 ).

Satisfaction of medical students with formative assessment of medical courses

To the best of our knowledge, this study was the first to survey undergraduate students covering clinical medicine, preventive medicine, public health, and nursing at a comprehensive Chinese university to analyse their perceptions, feedback, and satisfaction with implementation of student-centred FA in the medical curriculum. The results of this study indicate the necessity of medical students as subjects of FA, highlighting the concept of student-centred in three aspects: student cognition, empowered participation, and humanism. Of note is the value of student satisfaction as a measure of FA indicators.

Medical students have lower degree of understanding of FA, which hinders the efficiency and effectiveness of FA feedback. The survey results showed that 37.1% had a general understanding of FA, even though the instructor introduced students to the scoring of each task in the FA design during the first session of each course. In addition, only 45.2% of medical students clearly understood how each section of the FA was scored. This differs from the results of the FA methodology survey conducted with teachers, who were very clear about the methodology and purpose of FA [ 21 , 23 ], while students were not. Possible reasons for this are that medical students are vague about the pedagogical goals of each FA task, are not yet clear about the attitudes, emotions, and values of FA, and are only passively working with teachers and completing assigned tasks. Future medical educators can pay attention to medical students’ cognitive development of teaching assessment and guide them to self-reflect and adjust their learning activities independently [ 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 ]. Suppose students lack the motivation to learn independently. In that case, the advantages of student-centred FA may be reduced, and teachers ask students ground to complete large, simple, and more repetitive tasks without thinking about what they are doing or learning, and without enjoying the authentic sense of accomplishment and satisfaction that comes from learning or completing tasks.

The power-sharing of student-centred FA, with teachers playing the roles of organizers, managers, and collaborators, attempts to encourage students to shift from passive acceptance of assessment to active participation in assessment and to guide students to become the subjects of FA [ 38 , 42 ]. In our study, the scoring of FA, consisting of three components: student self-assessment, student mutual assessment, and teacher-student mutual assessment, consciously fostered the role of medical students as subjects in FA [ 43 ]. However, 94.2% of the medical students who participated in the survey perceived teaching and learning assessment as teacher-led, while 30% chose student-led. In contrast to the results of previous studies, traditional instructional assessment in medical curricula, which is dominated by instructor-led summative assessment, means that there is relatively little flexibility or opportunity to allow students to make decisions about their learning, thereby affecting their opportunities and motivation to participate in the assessment [ 24 , 44 ]. Although medical student-centred FA received high levels of student satisfaction, medical students have a more ambiguous sense of themselves as assessment subjects. They remain stuck in an outdated notion that the teacher is the assessment in traditional teaching assessments [ 27 , 41 ]. In addition, medical students reported in the open topic, their preference for using FA methods in the medical curriculum, and their preference for FA methods with an element of teacher-student interaction, reflecting their preference for classroom activities with immediate feedback. This differs from previous research findings in that traditional educational practices focus on teacher-led strategy implementation. In contrast, student-centred FA leaves decision-making about course activities to students, who are actively engaged by having a good experience in the interaction. Perhaps instructional assessment power-sharing with students is not the right way to assess student-centred instruction, but it represents a potentially effective way to do so.

Within the framework of student-centred theory, humanism focuses on understanding students’ aspirations, interests, and personalities and responding to them. The results of medical students’ satisfaction with each entry of FA in the survey showed that the mean score of the number of learning tasks reflected a low level of satisfaction, which is consistent with the results of previous FA satisfaction surveys [ 40 , 45 ]. It is possible that students perceive that participating and completing the learning tasks of FA, with more time and effort, is still in a sense the same as traditional teaching assessment, passively completing the learning tasks assigned by teachers. Although student satisfaction is regarded as an important indicator to test teaching assessment, it does not mean that educators should cater to student satisfaction and reduce the amount and number of learning tasks [ 46 ]. At the same time, humanism advocates that the advantage of student satisfaction is to improve formative assessment by including students’ learning efficiency or teaching behavior, to promote students’ in-depth learning in FA. It is worth noting that some teachers may damage or reduce the FA standard to meet the students’ satisfaction, which affects the effectiveness of teaching evaluation. Avoid biased teaching evaluation results due to the limitations of student satisfaction [ 47 ], which may require the FA evaluation index system indicators to be diversified and complete, consider the dimensions of educators’ teaching behavior [ 48 ], students’ feedback and satisfaction with teaching evaluation [ 49 ], improve the single and one-sided defect of FA evaluation index system, and expand the positive impact of student satisfaction on student centered FA, promote teachers’ teaching and students’ learning.

Our study has several limitations that we recommend that future studies consider and address. First, we analyse medical students’ perspectives on the implementing of FA in the medical course, but this does not represent the perspectives of students in other disciplines. The medical course has the educational goal of developing medical personnel with professional, clinical competence and a strong sense of empathy, which is somewhat different from the educational goals of other disciplines, and future replication in other fields is needed to be able to generalize these findings. Second, the survey was completed voluntarily by students. Although the 93.9% response rate was reasonable, the lack of effective participation by some medical students did introduce a selection bias that should be considered a potential limitation. Finally, this study was cross-sectional, conducted during an epidemic, lacking in-depth follow-up, and lacking consideration of whether students’ perspectives have changed as the FA progressed, focusing on medical students’ overall competency over a more extended time and their updated recommendations for the FA.

With the wide application of FA, students’ views and attitudes towards this kind of teaching assessment are becoming increasingly important. We identified the important value of students as participants and collaborators in FA. In addition, combined with student satisfaction, we suggest that medical educators avoid using student satisfaction as a single indicator to measure the teaching effectiveness of student-centred FA. In the future, they might also incorporate diverse assessment indicators to construct an assessment index system for FA to highlight the advantages of FA in medical curricula.

Data Availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Jiang XY, Ning QL. The impact and evaluation of COVID-19 pandemic on the teaching model of medical molecular biology course for undergraduates major in pharmacy. Biochem Mol Biol Educ. 2021;49(3):346–52.

Article Google Scholar

Chang WJ, Jiang YD, Xu JM. Experience of teaching and training for medical students at gastrointestinal surgery department under COVID-19 epidemic situation. Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2020;23(6):616–8. [In Chinese]

Google Scholar

Derar S. Transitioning from Face-to-Face to Remote Learning: Students’ Attitudes and Perceptions of using Zoom during COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Technology in Education and Science. 2020;4(4):335–342.

Lavercombe M. Changes to clinical education during the COVID-19 pandemic: Challenges and opportunities. Respirology. 2022;27(2):112–113.

Brady AK, Pradhan D. Learning without Borders: Asynchronous and Distance Learning in the age of COVID-19 and Beyond. Ats Scholar. 2020;1(3):233–242.

El-Maaddawy T. Enhancing Learning of Engineering Students Through Self-Assessment. Global Engineering Education Conference IEEE. 2017:86–91.

Gomez-Dantes H. Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Salud Publica Mex. 2011;53(2):199–200.

Kinio AE, Dufresne L, Brandys T, Jetty P. Break out of the Classroom: the use of escape rooms as an alternative teaching strategy in Surgical Education. J Surg Educ. 2019;76(1):134–139.

Wei B. COVID-19 and online teaching in higher education: A case study of Peking University. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies. 2020; 2:113–115.

He M, Tang XQ, Zhang HN, Luo YY, Tang ZC, Gao SG. Remote clinical training practice in the neurology internship during the COVID-19 pandemic. Med Educ Online. 2021;26(1):1899642.

Lepe JJ, Alexeeva A, Breuer JA, Greenberg ML. Transforming University of California, Irvine Medical Physiology Instruction into the Pandemic Era. FASEB BioAdvances, 2021;3:136–142.

Bond M, Buntins K, Bedenlier S, Zawacki-Richter O, Kerres M. Mapping research in student engagement and educational technology in higher education: a systematic evidence map. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education. 2020;17(2):1–30.

Ju Jiyu, Liu Linlin, Du Hongbin, Sun Mengying, Gao Zhiqin, Yu Wenjing, Zhao Chunling. The application of rain classroom mixed teaching mode in formative evaluation. China Higher Medical Education, 2022; 305(05):45–46. [In Chinese]

Neumann JW. Developing a New Framework for Conceptualizing “Student-Centered Learning”. The Educational Forum. 2013;77(2):161–175.

Starkey L. Three dimensions of student-centred education: a framework for policy and practice. Crit Stud Educ. 2019;60(3):375–90.

Schuh KL. Knowledge construction in the learner-centered classroom. J Educ Psychol. 2003;95(2):426–442.

Tangney S. Student-centred learning: a humanist perspective. Teach High Educ. 2014;19(3):266–275.

Wang XC. Experiences, challenges, and prospects of National Medical Licensing examination in China. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22(1):349.

Bremner N. The multiple meanings of ‘student-centred’ or ‘learner-centred’ education, and the case for a more flexible approach to defining it. Comp Educ. 2021;57(2):159–186.

Lim YS. Students’ Perception of Formative Assessment as an Instructional Tool in Medical Education. Medical Science Educator. 2019;29(1):255–263.

Yan Z, Pastore S. Assessing teachers’ strategies in Formative Assessment: the teacher formative Assessment Practice Scale. J Psychoeducational Assess. 2022;40(5):592–604.

Weurlander M, Soderberg M, Scheja M, Hult H, Wernerson A. Exploring formative assessment as a tool for learning: students’ experiences of different methods of formative assessment. Assess Evaluation High Educ. 2012;37(6):747–60.

Yan Z, Chiu MM, Cheng ECK. Predicting teachers’ formative assessment practices: Teacher personal and contextual factors. Teaching and Teacher Education. 2022;114:103718.

Fu XM, Wu XY, Liu DH, Zhang CY, Xie HL, Wang Y, Xiao LJ. Practice and exploration of the “student-centered” multielement fusion teaching mode in human anatomy. Surg Radiol Anat. 2022;44(1):15–23.

Silva J, Brown A, Atley J. Patient-centered medical education: medical students’ perspective. Med Teach. 2020;42(8):953.

Alsoufi A, Alsuyihili A, Msherghi A, Elhadi A, Atiyah H, Ashini A, Ashwieb A, Ghula M, Ben Hasan H, Abudabuos S, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on medical education: medical students’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding electronic learning. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(11):e0242905.

Harrison CJ, Konings KD, Schuwirth LWT, Wass V, van der Vleuten CPM. Changing the culture of assessment: the dominance of the summative assessment paradigm. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17:73.

Tam ACF. Undergraduate students’ perceptions of and responses to exemplar-based dialogic feedback. Assess Evaluation High Educ. 2021;46(2):269–85.

Noble C, Billett S, Armit L, Collier L, Molloy EJAiHSE. “It’s yours to take”: generating learner feedback literacy in the workplace. 2020, 25(1):55–74.

McGinness HT, Caldwell PHY, Gunasekera H, Scott KM. ‘Every Human Interaction Requires a Bit of Give and Take’: Medical Students’ Approaches to Pursuing Feedback in the Clinical Setting. Teaching and Learning in Medicine. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1080/10401334.2022.2084401

Ke FF, Kwak D. Constructs of Student-Centered Online Learning on Learning Satisfaction of a Diverse Online Student Body: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach. Journal of Educational Computing Research. 2013;48(1):97–122.

Tian M, Lu GS. Online learning satisfaction and its associated factors among international students in China. Front Psychol. 2022;13:916449.

George RJ, Kunjavara J, Kumar LM, Sam ST. Nursing students and online learning during COVID-19 pandemic: a scoping review. J Pharm Res Int. 2021;33(53B):268–273.

Deng RQ, Benckendorff P, Gannaway D. Progress and new directions for teaching and learning in MOOCs. Comput Educ. 2019;129:48–60.

Barclay C, Donalds C, Osei-Bryson KM. Investigating critical success factors in online learning environments in higher education systems in the Caribbean. Inform Technol Dev. 2018;24(3):582–611.

Firat M, Kilinc H, Yuzer TV. Level of intrinsic motivation of distance education students in e-learning environments. J Comput Assist Learn. 2018;34(1):63–70.

Wang WM. Medical education in china: progress in the past 70 years and a vision for the future. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(1):453.

Leenknecht M, Wijnia L, Kohlen M, Fryer L, Rikers R, Loyens S. Formative assessment as practice: the role of students’ motivation. Assess Evaluation High Educ. 2021;46(2):236–255.

Andrade HL, Brookhart SM. Classroom assessment as the co-regulation of learning. Assess Education-Principles Policy Pract. 2020;27(4):350–372.

Latjatih FD, Roslan NS, Kassim P, Adam SK. Medical students’ perception and satisfaction on peer-assisted learning in formative OSCE and its effectiveness in improving clinical competencies. J Appl Res High Educ. 2021;14(1):171–179.

Granberg C, Palm T, Palmberg B. A case study of a formative assessment practice and the effects on students’ self-regulated learning. Studies in Educational Evaluation. 2021;68:100955.

Hsih KW, Iscoe MS, Lupton JR, Mains TE, Nayar SK, Orlando MS, Parzuchowski AS, Sabbagh MF, Schulz JC, Shenderov K, et al. The Student Curriculum Review Team: how we catalyze curricular changes through a student-centered approach. Med Teach. 2015;37(11):1008–12.

Bozkurt F. Teacher Candidates’ Views On Self And Peer Assessment As A Tool For Student Development. Australian Journal of Teacher Education. 2020;45(1):47–60.

Geraghty JR, Young AN, Berkel TDM, Wallbruch E, Mann J, Park YS, Hirshfield LE, Hyderi A. Empowering medical students as agents of curricular change: a value-added approach to student engagement in medical education. Perspect Med Educ. 2020;9(1):60–5.

Cong X, Zhang Y, Xu H, Liu LM, Zheng M, Xiang RL, Wang JY, Jia S, Cai JY, Liu C, et al. The effectiveness of formative assessment in pathophysiology education from students’ perspective: a questionnaire study. Adv Physiol Educ. 2020;44(4):726–733.

Student-centred education. : a philosophy most unkind. Available from: https://www.timeshighereducation.com/depth/student-centred-education-philosophy-most-unkind

Yingjian G. Student-centred, Higher education institutions should have foresight and judgment. China Science Daily , Available from: https://news.sciencenet.cn/htmlnews/2022/7/482123.shtm

Martin F, Wang C, Sadaf A. Student perception of helpfulness of facilitation strategies that enhance instructor presence, connectedness, engagement and learning in online courses. Internet and Higher Education. 2018;37:52–65.

Wang R, Han JY, Liu CY, Wang LX. Relationship between medical students’ perceived instructor role and their approaches to using online learning technologies in a cloud-based virtual classroom. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22:560.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The author thanks the participating students for their help and kindness in sharing their experiences and opinions. Special thanks to Professor Yang Ning for her suggestions and support for the research.

This work was supported by the funds of Teacher teaching development research project of Jilin University[The construction of formative evaluation system based on the whole process of medical curriculum]; Higher Education Scientific Research Project of Jilin Association for Higher Education [JGJX2021C3, JGJX2022B7]; Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities[415010300093]; Jilin Province Health Science and Technology Capacity Improvement Project[2021GL005]; Jilin Provincial Science and Technology Development Plan Project[20220508065RC];Jilin University Education Reform and Research Support Project[2022JGY027]; Jilin University Graduate Ideological and Political Education Research Project[ysz202230]; Jilin Province Higher Education Teaching Reform Research Project[2021XZD054].

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Nursing, Jilin University, Changchun, Jilin Province, China

Tianjiao Ma, Hua Yuan, Feng Li & Jiannan Yao

School of Public Health, Jilin University, Changchun, Jilin Province, China

Yin Li, Shujuan Yang & Yongzhi Zhan

Division of Clinical Research, The First Hospital of Jilin University, Changchun, Jilin Province, China

Institute of Communication and Social Governance, Jilin University, China, Changchun, Jilin Province

Tianjiao Ma

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Tianjiao Ma and Yin Li made contributions to the study conception and design. Hua Yuan, Feng Li, Shujuan Yang, Jiannan Yao and Yongzhi Zhan made contributions to data collection. Tianjiao Ma and Yin Li contributed to data analysis and interpretation. Dongmei Mu contributed to the draft and critical revision of the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript for publication.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Dongmei Mu .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

The study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The ethical approval of this study was approved by the human research and ethics committee of the School of Nursing, Jilin University (2020092104) before starting this study. The study strictly followed the procedures of informed consent, non-harm, and confidentiality of participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Tianjiao Ma and Yin Li are co-senior authors.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1

Supplementary material 2, supplementary material 3, supplementary material 4, supplementary material 5, rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Ma, T., Li, Y., Yuan, H. et al. Reflection on the teaching of student-centred formative assessment in medical curricula: an investigation from the perspective of medical students. BMC Med Educ 23 , 141 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-023-04110-w

Download citation

Received : 10 October 2022

Accepted : 15 February 2023

Published : 02 March 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-023-04110-w

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Formative assessment

- Medical students

- Student-centred

- Student satisfaction

- Medical education

BMC Medical Education

ISSN: 1472-6920

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Numismatics

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Social History

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Meta-Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Legal System - Costs and Funding

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Restitution

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Social Issues in Business and Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Research Methodology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Social Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Sustainability

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- Ethnic Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Politics of Development

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Qualitative Political Methodology

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Disability Studies

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

41 Formative assessment

- Published: October 2013

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Assessment is a complex process, serving a wide range of differing functions. Formative assessment is a powerful driver for learning, involving a dynamic interaction between students and their teachers to drive up the quality of the educational process. Grounded in social constructivist theories of education, effective formative assessment, or assessment for learning, utilizes constructive feedback as the tool by which students gain confidence and skills in self-regulation and reflection as well as the autonomy required for lifelong learning. In a programme of formative assessment, students are aware of the learning outcomes of the curriculum and the requirements for success. They are encouraged to examine their learning needs in order achieve their goals and also to engage in assessment of their own work and that of their peers, thereby developing a deeper understanding of their subject. Within an educational institution, assessment procedures should be explicitly aligned with the intended learning outcomes so that both formative and summative assessments directly facilitate learning and are embedded in curriculum design and review. By placing assessment at the heart of learning, a well developed programme of formative assessment can be an effective way of influencing institutional culture, ensuring that data gathered from all forms of assessment are analysed and used in a programme of continuous educational improvement. Formative assessment is employed in all educational sectors and has particular relevance to medical education in which observed practice and experiential learning are central to the educational process. The valuable skills for lifelong learning which are fostered by effective formative assessment are a feature of medical education and a key requirement for good medical practice.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

- Google Scholar Indexing

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Assessment Methods in Undergraduate Medical Education

Nadia m al-wardy.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Received 2010 Jan 19; Revision requested 2010 Mar 30; Revised 2010 Apr 18; Accepted 2010 Apr 21; Issue date 2010 Aug; Collection date 2010.

Various assessment methods are available to assess clinical competence according to the model proposed by Miller. The choice of assessment method will depend on the purpose of its use: whether it is for summative purposes (promotion and certification), formative purposes (diagnosis, feedback and improvement) or both. Different characteristics of assessment tools are identified: validity, reliability, educational impact, feasibility and cost. Whatever the purpose, one assessment method will not assess all domains of competency, as each has its advantages and disadvantages; therefore a variety of assessment methods is required so that the shortcomings of one can be overcome by the advantages of another.

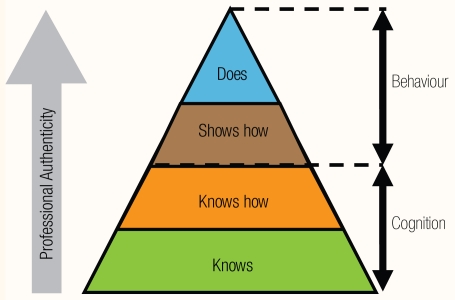

Keywords: Medical Education, Undergraduate, Assessment, Educational

In 1990, Miller proposed a hierarchical model for the assessment of clinical competence. 1 This model starts with the assessment of cognition and ends with the assessment of behaviour in practice [ Figure 1 ]. Professional authenticity increases as we move up the hierarchy and as assessment tasks resemble real practice. The assessment of cognition deals with knowledge and its application (knows, knows how) and this could span the levels of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives from the level of comprehension to the level of evaluation. 2 The assessment of behaviour deals with assessment of competence under controlled conditions (shows how) and the assessment of competence in practice or the assessment of performance (does). Different assessment tools are available which are appropriate for the different levels of the hierarchy. Van der Vleuten proposed a conceptual model for defining the utility of an assessment tool. 3 This is derived by conceptually multiplying several weighted criteria on which assessment tools can be judged. These criteria were validity (does it measure what it is supposed to be measuring?); reliability (does it consistently measure what it is supposed to be measuring?); educational impact (what are the effects on teaching and learning?); acceptability (is it acceptable to staff, students and other stakeholders?), and cost. The weighting of the criteria depended on the purpose for which the tool was used. For summative purposes, such as selection, promotion or certification, more weight was given to reliability while for formative purposes, such as diagnosis, feedback and improvement, more weight was given to educational impact. 4 Whatever the purpose of the assessment it is unlikely that one method will assess all domains of competency. A variety of assessment methods are, therefore, required. Since each assessment method has its own advantages and disadvantages, by employing a variety of assessment methods the shortcomings of one can be overcome by the advantages of another.

Miller’s hierarchical model for the assessment of clinical competence 1

This paper will not be an exhaustive review of all assessment methods reported in the literature, but only those with clear conclusions about their validity and reliability in the context of undergraduate medical education although many of them are also used in postgraduate medical education also. Some new trends, although still requiring further validation, will also be considered.

Assessment of Knowledge and its Application

The most common method for the assessment of knowledge is the written method (which can also be delivered online). Several written assessment formats are available to choose from. It should be noted, however, that in choosing any format, the question that is asked is more important than the format in which it is to be answered. In other words, it is the content of the question that determines what the question tests. 5 For example, sometimes, it is incorrectly assumed that multiple choice questions (MCQ) are unsuitable for testing problem solving ability because they require students to merely recognise the correct answer, while in open ended questions they have to generate the answer spontaneously. Multiple choice questions can test problem solving ability if constructed properly. 5 , 6 , 7 This does not exclude the fact that certain question formats are more suitable than others for asking certain types questions. For example, when an explanation is required, an essay question will, obviously, be more suitable than an MCQ.

Every question format has its own advantages and disadvantages which must be carefully weighed when a particular question type is chosen. It is not possible that one type of question will serve the purpose of testing all the aspects of a topic. Therefore, a variety of formats are needed to counter the possible bias associated with individual formats and they should be consistent with the stated objectives of the course or programme.

MULTIPLE CHOICE QUESTIONS (A-TYPE: ONE BEST ANSWER)

These are the most commonly used question type. They require examinees to select the single best response from 3 or more options. They are relatively easy to construct and enjoy high reliability per hour of testing since they can be used to sample a broad content domain. MCQs are often misconstrued as tests of simple facts, but, if constructed well, they can test the application of knowledge and problem solving skills. If questions are context-free, they almost exclusively test factual knowledge and the thought process involved is simple. 6 Contextualising the questions by including clinical or laboratory scenarios not only conveys authenticity and validity, but, also, is more likely to focus on important information rather than trivia. The thought process involved is also more complex with candidates weighing different units of information against each other when making a decision. 6 Examples of well constructed one best answer questions and guidelines about writing such questions can be found in Case and Swanson. 7

MULTIPLE CHOICE QUESTIONS (R-TYPE: EXTENDED MATCHING ITEMS)

One approach to context-rich questions is extended matching questions or extended matching items (EMQs or EMIs). 8 EMIs are organised into sets of short clinical vignettes or scenarios that use one list of options that are aimed at one aspect (e.g. all diagnoses, all laboratory investigations, etc). These options can range from 5 to 26 (although 8 options have been advocated to make more efficient use of testing time). 9 Some options may apply to more than one vignette while others may not apply at all. A well-constructed extended matching set includes four components: theme, options list, lead-in statement, and at least two item stems. An example and guidelines for writing such questions are shown in Case and Swanson. 7

KEY FEATURES QUESTIONS

Key features questions are short clinical cases or scenarios which are followed by questions aimed at key features or essential decisions of the case. 10 These questions can either be multiple choice or open ended questions. More than one correct answer can be provided. Key feature questions have been advocated to test clinical decision-making skills with demonstrated validity and reliability when constructed according to certain guidelines. 11 Although these questions are used in some “high-stakes” examinations in places such as Canada and Australia, 11 they are less well known than the other types and their construction is time consuming, especially if teachers are inexperienced question writers. 12

SHORT ANSWER QUESTIONS (SAQS)