The Three Most Common Types of Hypotheses

In this post, I discuss three of the most common hypotheses in psychology research, and what statistics are often used to test them.

- Post author By sean

- Post date September 28, 2013

- 37 Comments on The Three Most Common Types of Hypotheses

Simple main effects (i.e., X leads to Y) are usually not going to get you published. Main effects can be exciting in the early stages of research to show the existence of a new effect, but as a field matures the types of questions that scientists are trying to answer tend to become more nuanced and specific. In this post, I’ll briefly describe the three most common kinds of hypotheses that expand upon simple main effects – at least, the most common ones I’ve seen in my research career in psychology – as well as providing some resources to help you learn about how to test these hypotheses using statistics.

Incremental Validity

“Can X predict Y over and above other important predictors?”

This is probably the simplest of the three hypotheses I propose. Basically, you attempt to rule out potential confounding variables by controlling for them in your analysis. We do this because (in many cases) our predictor variables are correlated with each other. This is undesirable from a statistical perspective, but is common with real data. The idea is that we want to see if X can predict unique variance in Y over and above the other variables you include.

In terms of analysis, you are probably going to use some variation of multiple regression or partial correlations. For example, in my own work I’ve shown in the past that friendship intimacy as coded from autobiographical narratives can predict concern for the next generation over and above numerous other variables, such as optimism, depression, and relationship status ( Mackinnon et al., 2011 ).

“Under what conditions does X lead to Y?”

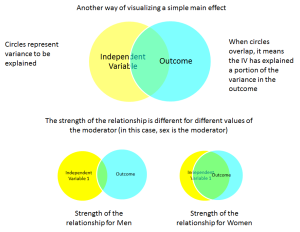

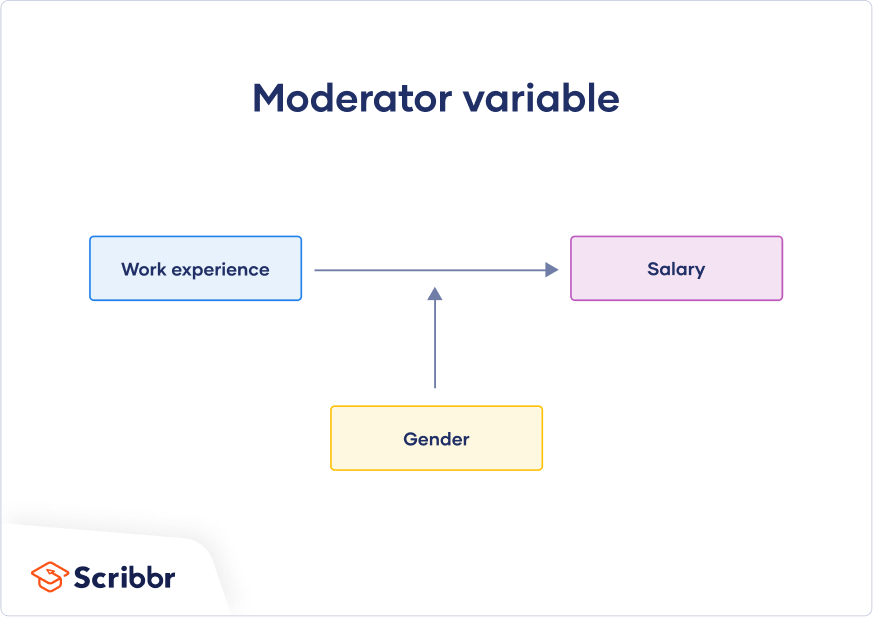

Of the three techniques I describe, moderation is probably the most tricky to understand. Essentially, it proposes that the size of a relationship between two variables changes depending upon the value of a third variable, known as a “moderator.” For example, in the diagram below you might find a simple main effect that is moderated by sex. That is, the relationship is stronger for women than for men:

With moderation, it is important to note that the moderating variable can be a category (e.g., sex) or it can be a continuous variable (e.g., scores on a personality questionnaire). When a moderator is continuous, usually you’re making statements like: “As the value of the moderator increases, the relationship between X and Y also increases.”

“Does X predict M, which in turn predicts Y?”

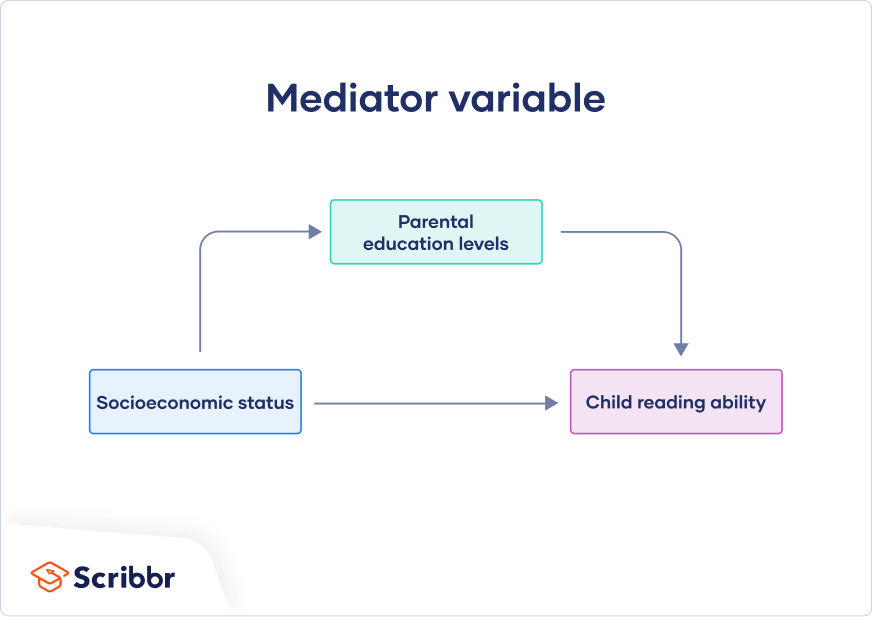

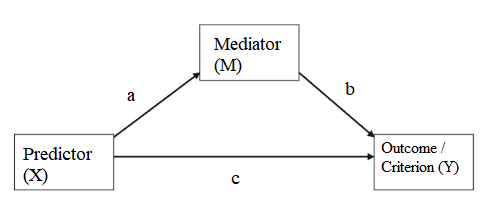

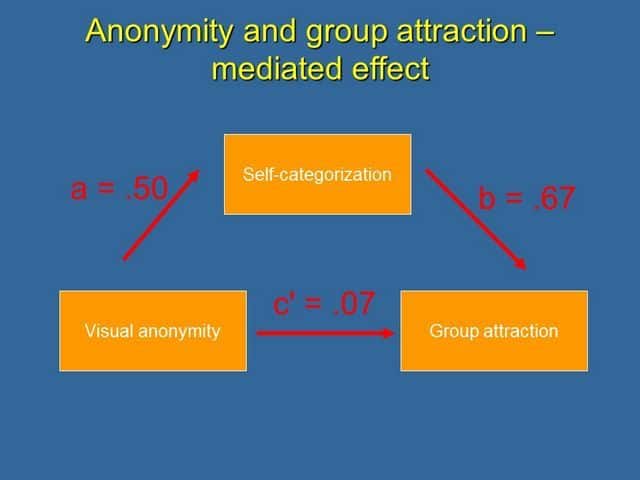

We might know that X leads to Y, but a mediation hypothesis proposes a mediating, or intervening variable. That is, X leads to M, which in turn leads to Y. In the diagram below I use a different way of visually representing things consistent with how people typically report things when using path analysis.

I use mediation a lot in my own research. For example, I’ve published data suggesting the relationship between perfectionism and depression is mediated by relationship conflict ( Mackinnon et al., 2012 ). That is, perfectionism leads to increased conflict, which in turn leads to heightened depression. Another way of saying this is that perfectionism has an indirect effect on depression through conflict.

Helpful links to get you started testing these hypotheses

Depending on the nature of your data, there are multiple ways to address each of these hypotheses using statistics. They can also be combined together (e.g., mediated moderation). Nonetheless, a core understanding of these three hypotheses and how to analyze them using statistics is essential for any researcher in the social or health sciences. Below are a few links that might help you get started:

Are you a little rusty with multiple regression? The basics of this technique are required for most common tests of these hypotheses. You might check out this guide as a helpful resource:

https://statistics.laerd.com/spss-tutorials/multiple-regression-using-spss-statistics.php

David Kenny’s Mediation Website provides an excellent overview of mediation and moderation for the beginner.

http://davidakenny.net/cm/mediate.htm

http://davidakenny.net/cm/moderation.htm

Preacher and Haye’s INDIRECT Macro is a great, easy way to implement mediation in SPSS software, and their MODPROBE macro is a useful tool for testing moderation.

http://afhayes.com/spss-sas-and-mplus-macros-and-code.html

If you want to graph the results of your moderation analyses, the excel calculators provided on Jeremy Dawson’s webpage are fantastic, easy-to-use tools:

http://www.jeremydawson.co.uk/slopes.htm

- Tags mediation , moderation , regression , tutorial

37 replies on “The Three Most Common Types of Hypotheses”

I want to see clearly the three types of hypothesis

Thanks for your information. I really like this

Thank you so much, writing up my masters project now and wasn’t sure whether one of my variables was mediating or moderating….Much clearer now.

Thank you for simplified presentation. It is clearer to me now than ever before.

Thank you. Concise and clear

hello there

I would like to ask about mediation relationship: If I have three variables( X-M-Y)how many hypotheses should I write down? Should I have 2 or 3? In other words, should I have hypotheses for the mediating relationship? What about questions and objectives? Should be 3? Thank you.

Hi Osama. It’s really a stylistic thing. You could write it out as 3 separate hypotheses (X -> Y; X -> M; M -> Y) or you could just write out one mediation hypotheses “X will have an indirect effect on Y through M.” Usually, I’d write just the 1 because it conserves space, but either would be appropriate.

Hi Sean, according to the three steps model (Dudley, Benuzillo and Carrico, 2004; Pardo and Román, 2013)., we can test hypothesis of mediator variable in three steps: (X -> Y; X -> M; X and M -> Y). Then, we must use the Sobel test to make sure that the effect is significant after using the mediator variable.

Yes, but this is older advice. Best practice now is to calculate an indirect effect and use bootstrapping, rather than the causal steps approach and the more out-dated Sobel test. I’d recommend reading Hayes (2018) book for more info:

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (2nd ed). Guilford Publications.

Hi! It’s been really helpful but I still don’t know how to formulate the hypothesis with my mediating variable.

I have one dependent variable DV which is formed by DV1 and DV2, then I have MV (mediating variable), and then 2 independent variables IV1, and IV2.

How many hypothesis should I write? I hope you can help me 🙂

Thank you so much!!

If I’m understanding you correctly, I guess 2 mediation hypotheses:

IV1 –> Med –> DV1&2 IV2 –> Med –> DV1&2

Thank you so much for your quick answer! ^^

Could you help me formulate my research question? English is not my mother language and I have trouble choosing the right words. My x = psychopathy y = aggression m = deficis in emotion recognition

thank you in advance

I have mediator and moderator how should I make my hypothesis

Can you have a negative partial effect? IV – M – DV. That is my M will have negative effect on the DV – e.g Social media usage (M) will partial negative mediate the relationship between father status (IV) and social connectedness (DV)?

Thanks in advance

Hi Ashley. Yes, this is possible, but often it means you have a condition known as “inconsistent mediation” which isn’t usually desirable. See this entry on David Kenny’s page:

Or look up “inconsistent mediation” in this reference:

MacKinnon, D. P., Fairchild, A. J., & Fritz, M. S. (2007). Mediation analysis. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 593-614.

This is very interesting presentation. i love it.

This is very interesting and educative. I love it.

Hello, you mentioned that for the moderator, it changes the relationship between iv and dv depending on its strength. How would one describe a situation where if the iv is high iv and dv relationship is opposite from when iv is low. And then a 3rd variable maybe the moderator increases dv when iv is low and decreases dv when iv is high.

This isn’t problematic for moderation. Moderation just proposes that the magnitude of the relationship changes as levels of the moderator changes. If the sign flips, probably the original relationship was small. Sometimes people call this a “cross-over” effect, but really, it’s nothing special and can happen in any moderation analysis.

i want to use an independent variable as moderator after this i will have 3 independent variable and 1 dependent variable…. my confusion is do i need to have some past evidence of the X variable moderate the relationship of Y independent variable and Z dependent variable.

Dear Sean It is really helpful as my research model will use mediation. Because I still face difficulty in developing hyphothesis, can you give examples ? Thank you

Hi! is it possible to have all three pathways negative? My regression analysis showed significant negative relationships between x to y, x to m and m to y.

Hi, I have 1 independent variable, 1 dependent variable and 4 mediating variable May I know how many hypothesis should I develop?

Hello I have 4 IV , 1 mediating Variable and 1 DV

My model says that 4 IVs when mediated by 1MV leads to 1 Dv

Pls tell me how to set the hypothesis for mediation

Hi I have 4 IVs ,2 Mediating Variables , 1DV and 3 Outcomes (criterion variables).

Pls can u tell me how many hypotheses to set.

Thankyou in advance

I am in fact happy to read this webpage posts which carries tons of useful information, thanks for providing such data.

I see you don’t monetize savvystatistics.com, don’t waste your traffic, you can earn additional bucks every month with new monetization method. This is the best adsense alternative for any type of website (they approve all websites), for more info simply search in gooogle: murgrabia’s tools

what if the hypothesis and moderator significant in regrestion and insgificant in moderation?

Thank you so much!! Your slide on the mediator variable let me understand!

Very informative material. The author has used very clear language and I would recommend this for any student of research/

Hi Sean, thanks for the nice material. I have a question: for the second type of hypothesis, you state “That is, the relationship is stronger for men than for women”. Based on the illustration, wouldn’t the opposite be true?

Yes, your right! I updated the post to fix the typo, thank you!

I have 3 independent variable one mediator and 2 dependant variable how many hypothesis I have 2 write?

Sounds like 6 mediation hypotheses total:

X1 -> M -> Y1 X2 -> M -> Y1 X3 -> M -> Y1 X1 -> M -> Y2 X2 -> M -> Y2 X3 -> M -> Y2

Clear explanation! Thanks!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- Mediator vs. Moderator Variables | Differences & Examples

Mediator vs. Moderator Variables | Differences & Examples

Published on March 1, 2021 by Pritha Bhandari . Revised on June 22, 2023.

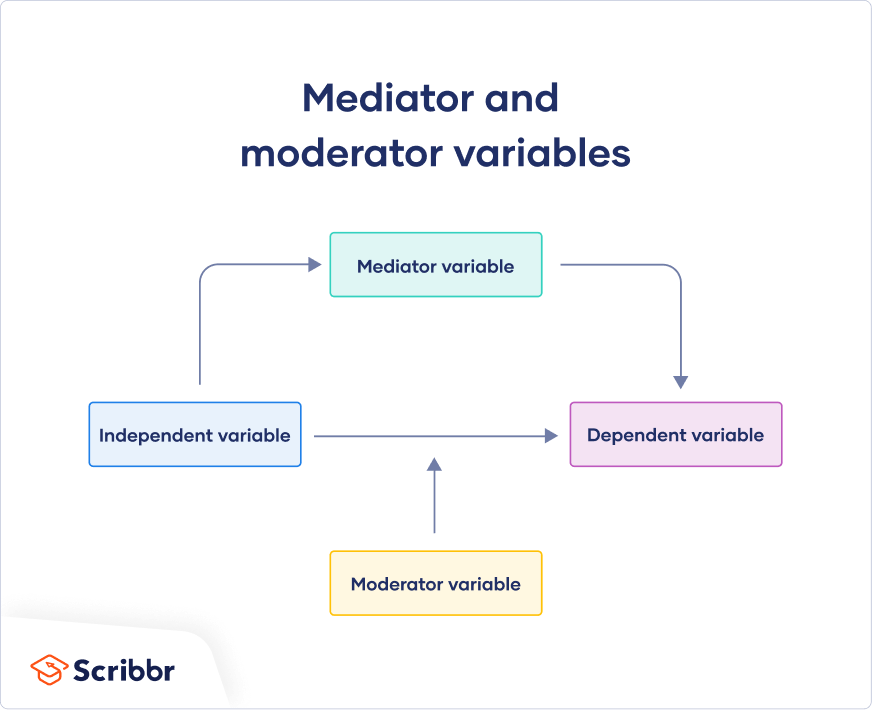

A mediating variable (or mediator ) explains the process through which two variables are related, while a moderating variable (or moderator ) affects the strength and direction of that relationship.

Including mediators and moderators in your research helps you go beyond studying a simple relationship between two variables for a fuller picture of the real world. These variables are important to consider when studying complex correlational or causal relationships between variables.

Including these variables can also help you avoid or mitigate several research biases , like observer bias , survivorship bias , undercoverage bias , or omitted variable bias

Table of contents

What’s the difference, mediating variables, moderating variables, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about mediators and moderators.

You can think of a mediator as a go-between for two variables. For example, sleep quality (an independent variable ) can affect academic achievement (a dependent variable) through the mediator of alertness. In a mediation relationship, you can draw an arrow from an independent variable to a mediator and then from the mediator to the dependent variable.

In contrast, a moderator is something that acts upon the relationship between two variables and changes its direction or strength. For example, mental health status may moderate the relationship between sleep quality and academic achievement: the relationship might be stronger for people without diagnosed mental health conditions than for people with them.

In a moderation relationship, you can draw an arrow from the moderator to the relationship between an independent and dependent variable.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

A mediator is a way in which an independent variable impacts a dependent variable. It’s part of the causal pathway of an effect, and it tells you how or why an effect takes place.

If something is a mediator:

- It’s caused by the independent variable.

- It influences the dependent variable

- When it’s taken into account, the statistical correlation between the independent and dependent variables is higher than when it isn’t considered.

Mediation analysis is a way of statistically testing whether a variable is a mediator using linear regression analyses or ANOVAs .

In full mediation , a mediator fully explains the relationship between the independent and dependent variable: without the mediator in the model, there is no relationship.

In partial mediation , there is still a statistical relationship between the independent and dependent variable even when the mediator is taken out of a model: the mediator only partially explains the relationship.

You use a descriptive research design for this study. After collecting data on each of these variables, you perform statistical analysis to check whether:

- Socioeconomic status predicts parental education levels,

- Parental education levels predicts child reading ability,

- The correlation between socioeconomic status and child reading ability is greater when parental education levels are taken into account in your model.

A moderator influences the level, direction, or presence of a relationship between variables. It shows you for whom, when, or under what circumstances a relationship will hold.

Moderators usually help you judge the external validity of your study by identifying the limitations of when the relationship between variables holds. For example, while social media use can predict levels of loneliness, this relationship may be stronger for adolescents than for older adults. Age is a moderator here.

Moderators can be:

- Categorical variables such as ethnicity, race, religion, favorite colors, health status, or stimulus type,

- Quantitative variables such as age, weight, height, income, or visual stimulus size.

- years of work experience predicts salary, when controlling for relevant variables,

- gender identity moderates the relationship between work experience and salary.

This means that the relationship between years of experience and salary would differ between men, women, and those who do not identify as men or women.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Ecological validity

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

A mediator variable explains the process through which two variables are related, while a moderator variable affects the strength and direction of that relationship.

A confounder is a third variable that affects variables of interest and makes them seem related when they are not. In contrast, a mediator is the mechanism of a relationship between two variables: it explains the process by which they are related.

Including mediators and moderators in your research helps you go beyond studying a simple relationship between two variables for a fuller picture of the real world. They are important to consider when studying complex correlational or causal relationships.

Mediators are part of the causal pathway of an effect, and they tell you how or why an effect takes place. Moderators usually help you judge the external validity of your study by identifying the limitations of when the relationship between variables holds.

If something is a mediating variable :

- It’s caused by the independent variable .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Bhandari, P. (2023, June 22). Mediator vs. Moderator Variables | Differences & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved August 2, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/mediator-vs-moderator/

Is this article helpful?

Pritha Bhandari

Other students also liked, independent vs. dependent variables | definition & examples, control variables | what are they & why do they matter, confounding variables | definition, examples & controls, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Mediator Variable / Mediating Variable: Simple Definition

Types of Variables >

A mediator variable explains the how or why of an (observed) relationship between an independent variable and its dependent variable .

In a mediation model, the independent variable cannot influence the dependent variable directly, and instead does so by means of a third variable, a ‘middle-man’.

In psychology, the mediator variable is sometimes called an intervening variable . In statistics, an intervening variable is usually considered to be a sub-type of mediating variable. However, the lines between the two terms are somewhat fuzzy, and they are often used interchangeably.

Mediator Variable Examples

A mediator variable may be something as simple as a psychological response to given events . For example, suppose buying pizza for a work party leads to positive morale and to the work being done in half the time.

- Pizza is the independent variable,

- Work speed is the dependent variable,

- The mediator, the middle man without which there would be no connection, is positive morale .

Although we may observe a definite effect on work speed when and if pizza is bought, the pizza itself does not have the power to affect work rates: only by affecting morale of the workers can it make an actual difference.

Full Mediation and Partial Mediation

Full mediation is when the entire relationship between the independent & dependent variables is through the mediator variable. If you take away the mediator, the relationship disappears. Since the real world is a complicated place with many interactions, this is less common than partial mediation.

Partial mediation happens when the mediating variable is only responsible for a part of the relationship between independent & dependent variables. If the mediating variable is eliminated, there will still be a relationship between the independent and dependent variables; it just won’t be as strong.

Mediational Hypotheses

Mediational hypotheses, by definition, include full (complete) mediation. In other words, the independent variable has zero effect on the dependent variable; the causal relationship depends entirely on the mediator.

Baron and Kenny’s Four Steps

Baron and Kenny (1986), Judd and Kenny (1981), and James and Brett (1984) outlined the following steps to identify the mediational hypothesis. If the steps are met, then variable M is said to completely mediate the X-Y relationship. The steps are

- Show that a the independent variable (X) is correlated with the mediator (M).

- Demonstrate that the dependent variable (Y) and M are correlated .

- Demonstrate full mediation on the process. The effect of X on Y, controlling for M (i.e. controlling for paths a and b in the image at the top of this page), should be zero. If the results for this step are anything but zero, then there is partial mediation.

The authors state that three regression analyses are needed:

- X as the predictor variable and M as the outcome variable .

- X as the predictor variable and Y as the outcome variable.

- X and M as the predictor variables and Y as the outcome variable.

The procedures come with some hefty explanations, which are beyond the scope of this article. I recommend reading Baron and Keny’s original text. Or, as an excellent (plain English) alternative, read Paul Jose’s Doing Statistical Mediation and Moderation: Methodology in the Social Sciences , which includes Baron and Kenny’s steps starting on page 20.

Mediator versus Moderator variables. Retrieved from http://psych.wisc.edu/henriques/mediator.html on June 26, 2018. Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173-1182. Retrieved June 26, 2018 from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.169.4836&rep=rep1&type=pdf on June 26, 2018 Butler, Adam. Mediation Defined. Retrieved from https://sites.uni.edu/butlera/courses/org/modmed/moderator_mediator.htm on June 26, 2018

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Chapter 2: Indexing

- Chapter 3: Loops & Logicals

- Chapter 4: Apply Family

- Chapter 5: Plyr Package

- Chapter 6: Vectorizing

- Chapter 7: Sample & Replicate

- Chapter 8: Melting & Casting

- Chapter 9: Tidyr Package

- Chapter 10: GGPlot1: Basics

- Chapter 11: GGPlot2: Bars & Boxes

- Chapter 12: Linear & Multiple

- Chapter 13: Ploting Interactions

- Chapter 14: Moderation/Mediation

- Chapter 15: Moderated-Mediation

- Chapter 16: MultiLevel Models

- Chapter 17: Mixed Models

- Chapter 18: Mixed Assumptions Testing

- Chapter 19: Logistic & Poisson

- Chapter 20: Between-Subjects

- Chapter 21: Within- & Mixed-Subjects

- Chapter 22: Correlations

- Chapter 23: ARIMA

- Chapter 24: Decision Trees

- Chapter 25: Signal Detection

- Chapter 26: Intro to Shiny

- Chapter 27: ANOVA Variance

- Download Rmd

Chapter 14: Mediation and Moderation

Alyssa blair, 1 what are mediation and moderation.

Mediation analysis tests a hypothetical causal chain where one variable X affects a second variable M and, in turn, that variable affects a third variable Y. Mediators describe the how or why of a (typically well-established) relationship between two other variables and are sometimes called intermediary variables since they often describe the process through which an effect occurs. This is also sometimes called an indirect effect. For instance, people with higher incomes tend to live longer but this effect is explained by the mediating influence of having access to better health care.

In R, this kind of analysis may be conducted in two ways: Baron & Kenny’s (1986) 4-step indirect effect method and the more recent mediation package (Tingley, Yamamoto, Hirose, Keele, & Imai, 2014). The Baron & Kelly method is among the original methods for testing for mediation but tends to have low statistical power. It is covered in this chapter because it provides a very clear approach to establishing relationships between variables and is still occassionally requested by reviewers. However, the mediation package method is highly recommended as a more flexible and statistically powerful approach.

Moderation analysis also allows you to test for the influence of a third variable, Z, on the relationship between variables X and Y. Rather than testing a causal link between these other variables, moderation tests for when or under what conditions an effect occurs. Moderators can stength, weaken, or reverse the nature of a relationship. For example, academic self-efficacy (confidence in own’s ability to do well in school) moderates the relationship between task importance and the amount of test anxiety a student feels (Nie, Lau, & Liau, 2011). Specifically, students with high self-efficacy experience less anxiety on important tests than students with low self-efficacy while all students feel relatively low anxiety for less important tests. Self-efficacy is considered a moderator in this case because it interacts with task importance, creating a different effect on test anxiety at different levels of task importance.

In general (and thus in R), moderation can be tested by interacting variables of interest (moderator with IV) and plotting the simple slopes of the interaction, if present. A variety of packages also include functions for testing moderation but as the underlying statistical approaches are the same, only the “by hand” approach is covered in detail in here.

Finally, this chapter will cover these basic mediation and moderation techniques only. For more complicated techniques, such as multiple mediation, moderated mediation, or mediated moderation please see the mediation package’s full documentation.

1.1 Getting Started

If necessary, review the Chapter on regression. Regression test assumptions may be tested with gvlma . You may load all the libraries below or load them as you go along. Review the help section of any packages you may be unfamiliar with ?(packagename).

2 Mediation Analyses

Mediation tests whether the effects of X (the independent variable) on Y (the dependent variable) operate through a third variable, M (the mediator). In this way, mediators explain the causal relationship between two variables or “how” the relationship works, making it a very popular method in psychological research.

Both mediation and moderation assume that there is little to no measurement error in the mediator/moderator variable and that the DV did not CAUSE the mediator/moderator. If mediator error is likely to be high, researchers should collect multiple indicators of the construct and use SEM to estimate latent variables. The safest ways to make sure your mediator is not caused by your DV are to experimentally manipulate the variable or collect the measurement of your mediator before you introduce your IV.

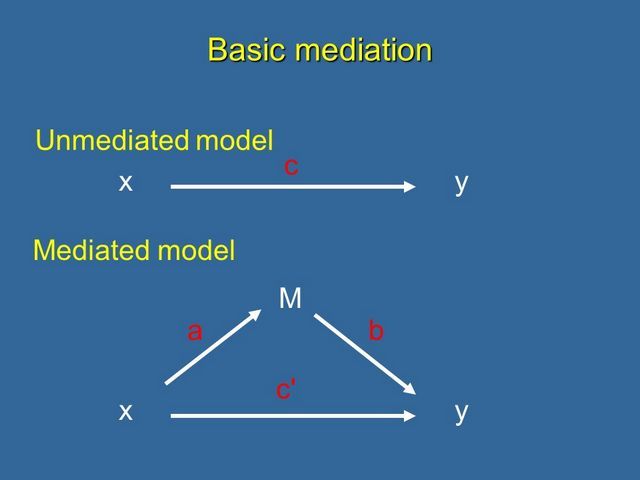

Total Effect Model.

Basic Mediation Model.

c = the total effect of X on Y c = c’ + ab c’= the direct effect of X on Y after controlling for M; c’=c-ab ab= indirect effect of X on Y

The above shows the standard mediation model. Perfect mediation occurs when the effect of X on Y decreases to 0 with M in the model. Partial mediation occurs when the effect of X on Y decreases by a nontrivial amount (the actual amount is up for debate) with M in the model.

2.1 Example Mediation Data

Set an appropriate working directory and generate the following data set.

In this example we’ll say we are interested in whether the number of hours since dawn (X) affect the subjective ratings of wakefulness (Y) 100 graduate students through the consumption of coffee (M).

Note that we are intentionally creating a mediation effect here (because statistics is always more fun if we have something to find) and we do so below by creating M so that it is related to X and Y so that it is related to M. This creates the causal chain for our analysis to parse.

2.2 Method 1: Baron & Kenny

This is the original 4-step method used to describe a mediation effect. Steps 1 and 2 use basic linear regression while steps 3 and 4 use multiple regression. For help with regression, see Chapter 10.

The Steps: 1. Estimate the relationship between X on Y (hours since dawn on degree of wakefulness) -Path “c” must be significantly different from 0; must have a total effect between the IV & DV

Estimate the relationship between X on M (hours since dawn on coffee consumption) -Path “a” must be significantly different from 0; IV and mediator must be related.

Estimate the relationship between M on Y controlling for X (coffee consumption on wakefulness, controlling for hours since dawn) -Path “b” must be significantly different from 0; mediator and DV must be related. -The effect of X on Y decreases with the inclusion of M in the model

Estimate the relationship between Y on X controlling for M (wakefulness on hours since dawn, controlling for coffee consumption) -Should be non-significant and nearly 0.

2.3 Interpreting Barron & Kenny Results

Here we find that our total effect model shows a significant positive relationship between hours since dawn (X) and wakefulness (Y). Our Path A model shows that hours since down (X) is also positively related to coffee consumption (M). Our Path B model then shows that coffee consumption (M) positively predicts wakefulness (Y) when controlling for hours since dawn (X). Finally, wakefulness (Y) does not predict hours since dawn (X) when controlling for coffee consumption (M).

Since the relationship between hours since dawn and wakefulness is no longer significant when controlling for coffee consumption, this suggests that coffee consumption does in fact mediate this relationship. However, this method alone does not allow for a formal test of the indirect effect so we don’t know if the change in this relationship is truly meaningful.

There are two primary methods for formally testing the significance of the indirect test: the Sobel test & bootstrapping (covered under the mediatation method).

The Sobel Test uses a specialized t-test to determine if there is a significant reduction in the effect of X on Y when M is present. Using the sobel function of the multilevel package will show provide you with three of the basic models we ran before (Mod1 = Total Effect; Mod2 = Path B; and Mod3 = Path A) as well as an estimate of the indirect effect, the standard error of that effect, and the z-value for that effect. You can either use this value to calculate your p-value or run the mediation.test function from the bda package to receive a p-value for this estimate.

In this case, we can now confirm that the relationship between hours since dawn and feelings of wakefulness are significantly mediated by the consumption of coffee (z’ = 3.84, p < .001).

However, the Sobel Test is largely considered an outdated method since it assumes that the indirect effect (ab) is normally distributed and tends to only have adequate power with large sample sizes. Thus, again, it is highly recommended to use the mediation bootstrapping method instead.

2.4 Method 2: The Mediation Pacakge Method

This package uses the more recent bootstrapping method of Preacher & Hayes (2004) to address the power limitations of the Sobel Test. This method computes the point estimate of the indirect effect (ab) over a large number of random sample (typically 1000) so it does not assume that the data are normally distributed and is especially more suitable for small sample sizes than the Barron & Kenny method.

To run the mediate function, we will again need a model of our IV (hours since dawn), predicting our mediator (coffee consumption) like our Path A model above. We will also need a model of the direct effect of our IV (hours since dawn) on our DV (wakefulness), when controlling for our mediator (coffee consumption). When can then use mediate to repeatedly simulate a comparsion between these models and to test the signifcance of the indirect effect of coffee consumption.

2.5 Interpreting Mediation Results

The mediate function gives us our Average Causal Mediation Effects (ACME), our Average Direct Effects (ADE), our combined indirect and direct effects (Total Effect), and the ratio of these estimates (Prop. Mediated). The ACME here is the indirect effect of M (total effect - direct effect) and thus this value tells us if our mediation effect is significant.

In this case, our fitMed model again shows a signifcant affect of coffee consumption on the relationship between hours since dawn and feelings of wakefulness, (ACME = .28, p < .001) with no direct effect of hours since dawn (ADE = -0.11, p = .27) and significant total effect ( p < .05).

We can then bootstrap this comparison to verify this result in fitMedBoot and again find a significant mediation effect (ACME = .28, p < .001) and no direct effect of hours since dawn (ADE = -0.11, p = .27). However, with increased power, this analysis no longer shows a significant total effect ( p = .08).

3 Moderation Analyses

Moderation tests whether a variable (Z) affects the direction and/or strength of the relation between an IV (X) and a DV (Y). In other words, moderation tests for interactions that affect WHEN relationships between variables occur. Moderators are conceptually different from mediators (when versus how/why) but some variables may be a moderator or a mediator depending on your question. See the mediation package documentation for ways of testing more complicated mediated moderation/moderated mediation relationships.

Like mediation, moderation assumes that there is little to no measurement error in the moderator variable and that the DV did not CAUSE the moderator. If moderator error is likely to be high, researchers should collect multiple indicators of the construct and use SEM to estimate latent variables. The safest ways to make sure your moderator is not caused by your DV are to experimentally manipulate the variable or collect the measurement of your moderator before you introduce your IV.

Basic Moderation Model.

3.1 Example Moderation Data

In this example we’ll say we are interested in whether the relationship between the number of hours of sleep (X) a graduate student receives and the attention that they pay to this tutorial (Y) is influenced by their consumption of coffee (Z). Here we create the moderation effect by making our DV (Y) the product of levels of the IV (X) and our moderator (Z).

3.2 Moderation Analysis

Moderation can be tested by looking for significant interactions between the moderating variable (Z) and the IV (X). Notably, it is important to mean center both your moderator and your IV to reduce multicolinearity and make interpretation easier. Centering can be done using the scale function, which subtracts the mean of a variable from each value in that variable. For more information on the use of centering, see ?scale and any number of statistical textbooks that cover regression (we recommend Cohen, 2008).

A number of packages in R can also be used to conduct and plot moderation analyses, including the moderate.lm function of the QuantPsyc package and the pequod package. However, it is simple to do this “by hand” using traditional multiple regression, as shown here, and the underlying analysis (interacting the moderator and the IV) in these packages is identical to this approach. The rockchalk package used here is one of many graphing and plotting packages available in R and was chosen because it was especially designed for use with regression analyses (unlike the more general graphing options described in Chapters 8 & 9).

3.3 Interpreting Moderation Results

Results are presented similar to regular multiple regression results (see Chapter 10). Since we have significant interactions in this model, there is no need to interpret the separate main effects of either our IV or our moderator.

Our by hand model shows a significant interaction between hours slept and coffee consumption on attention paid to this tutorial (b = .23, SE = .04, p < .001). However, we’ll need to unpack this interaction visually to get a better idea of what this means.

The rockchalk function will automatically plot the simple slopes (1 SD above and 1 SD below the mean) of the moderating effect. This figure shows that those who drank less coffee (the black line) paid more attention with the more sleep that they got last night but paid less attention overall that average (the red line). Those who drank more coffee (the green line) paid more when they slept more as well and paid more attention than average. The difference in the slopes for those who drank more or less coffee shows that coffee consumption moderates the relationship between hours of sleep and attention paid.

4 References and Further Reading

Baron, R., & Kenny, D. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173-1182.

Cohen, B. H. (2008). Explaining psychological statistics. John Wiley & Sons.

Imai, K., Keele, L., & Tingley, D. (2010). A general approach to causal mediation analysis. Psychological methods, 15(4), 309.

MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., Hoffman, J. M., West, S. G., & Sheets, V. (2002). A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological methods, 7(1), 83.

Nie, Y., Lau, S., & Liau, A. K. (2011). Role of academic self-efficacy in moderating the relation between task importance and test anxiety. Learning and Individual Differences, 21(6), 736-741.

Tingley, D., Yamamoto, T., Hirose, K., Keele, L., & Imai, K. (2014). Mediation: R package for causal mediation analysis.

15 Mediating Variable Examples

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

Learn about our Editorial Process

A mediating variable is a factor that explains the process through which an independent variable affects a dependent variable.

Here is a scholarly definition from Veronica Hefner (2017):

“A mediating variable is a variable that links the independent and the dependent variables , and whose existence explains the relationship between the other two variables. A mediating variable is also known as a mediator variable or an intervening variable.”

For example, in a study exploring the link between exercise and mental well-being, self-esteem might serve as a mediating variable, meaning that exercise boosts self-esteem, which then enhances mental well-being. It is that hidden ‘middle step’.

Mediating Variable Examples

1. the link between social media usage and loneliness.

Independent Variable: Social media usage Dependent Variable: Feelings of loneliness Mediating Variable: Quality and frequency of face-to-face interactions

If social media usage reduces the amount or quality of face-to-face time with others, it can lead to feelings of loneliness. Therefore, the relationship between extensive social media usage and feelings of loneliness might be mediated by the diminished quality and frequency of in-person interactions.

2. The Link Between Physical Activity and Mental Health

Independent Variable: Physical activity Dependent Variable: Improved mental health Mediating Variable: Endorphin release

When an individual engages in physical activity, the body releases endorphins, which are known as “feel-good” hormones. These endorphins play a significant role in enhancing mood and reducing feelings of anxiety and depression. Therefore, the positive relationship between physical activity and improved mental health might be mediated by the release of endorphins.

3. The Link Between Sleep Duration and Academic Performance

Independent Variable: Sleep duration Dependent Variable: Academic performance Mediating Variable: Cognitive function and attention span

Adequate sleep duration is crucial for optimal cognitive functioning and attention span. When students get adequate sleep, their cognitive abilities like memory, decision-making, and problem-solving are enhanced, leading to better academic performance. Thus, the relationship between sleep duration and academic performance might be mediated by improvements in cognitive function and sustained attention span.

4. The Link Between Job Satisfaction and Employee Turnover

Independent Variable: Job satisfaction Dependent Variable: Employee turnover Mediating Variable: Organizational commitment

Employees who are satisfied with their job are more likely to develop a stronger commitment to their organization. This commitment often results in greater loyalty and a decreased likelihood to leave the company. Therefore, the relationship between job satisfaction and reduced employee turnover might be mediated by the increased sense of organizational commitment.

5. The Link Between Dietary Habits and Physical Health

Independent Variable: Dietary habits Dependent Variable: Physical health Mediating Variable: Nutrient intake

If someone consistently consumes a balanced diet, they intake essential nutrients that promote good health. The relationship between dietary habits and physical health might be mediated by the level of essential nutrients consumed, ensuring proper body function and preventing deficiencies.

6. The Link Between Classroom Environment and Student Engagement

Independent Variable: Classroom environment Dependent Variable: Student engagement Mediating Variable: Student’s perception of safety and belonging

A positive and inclusive classroom environment can make students feel safe and like they belong. When students perceive that they are in a safe environment where they are valued, they are more likely to engage actively in learning. Thus, the relationship between the classroom environment and student engagement might be mediated by the student’s feelings of safety and belonging.

7. The Link Between Work-Life Balance and Employee Burnout

Independent Variable: Work-life balance Dependent Variable: Employee burnout Mediating Variable: Stress levels

Employees with a poor work-life balance often experience heightened stress levels due to the overlapping demands of their job and personal life. Elevated stress levels over extended periods can lead to feelings of burnout. Therefore, the relationship between work-life balance and employee burnout might be mediated by the levels of stress an employee experiences.

8. The Link Between Urban Green Spaces and Mental Well-being

Independent Variable: Presence of urban green spaces Dependent Variable: Mental well-being Mediating Variable: Frequency of nature interactions

When urban areas have more green spaces, residents tend to interact more frequently with nature, either by walking, exercising, or simply spending time in these areas. These interactions with nature have been shown to reduce stress and increase feelings of relaxation. Therefore, the relationship between the presence of urban green spaces and mental well-being might be mediated by the frequency of nature interactions.

9. The Link Between Employee Training and Job Performance

Independent Variable: Employee training Dependent Variable: Job performance Mediating Variable: Skill acquisition and competence

Regular and quality employee training sessions equip employees with new skills and enhance their competence in their roles. As they become more skilled and competent, their performance at their job tends to improve. Thus, the relationship between employee training and job performance might be mediated by the level of skill acquisition and competence achieved.

10. The Link Between Plant Ownership and Reduced Stress

Independent Variable: Plant ownership Dependent Variable: Reduced stress Mediating Variable: Increased interaction with nature and nurturing behavior

Caring for plants allows individuals to interact with nature even in indoor environments. Additionally, the act of nurturing plants and seeing them grow can be therapeutic and rewarding. These interactions and behaviors can lead to relaxation and a reduction in stress levels. Therefore, the relationship between plant ownership and reduced stress might be mediated by the increased interaction with nature and the nurturing behavior associated with plant care.

11. The Link Between Music Lessons and Cognitive Development

Independent Variable: Music lessons Dependent Variable: Cognitive development Mediating Variable: Development of discipline and concentration

Engaging in music lessons often requires students to practice regularly, fostering discipline. Additionally, mastering an instrument necessitates concentration and focus. These attributes can positively impact other areas of life, including academic pursuits. Thus, the relationship between music lessons and cognitive development might be mediated by the enhanced discipline and concentration developed through musical practice.

12. The Link Between Outdoor Play and Physical Health in Children

Independent Variable: Outdoor play Dependent Variable: Physical health in children Mediating Variable: Physical activity levels

Children who engage in outdoor play are often more physically active than those who spend more time indoors, as they run, jump, climb, and engage in other physical activities. This increased level of physical activity is essential for cardiovascular health, muscle development, and overall physical well-being. Therefore, the relationship between outdoor play and physical health in children might be mediated by the levels of physical activity they engage in.

13. The Link Between Personal Financial Management and Life Satisfaction

Independent Variable: Personal financial management Dependent Variable: Life satisfaction Mediating Variable: Financial security and reduced monetary stress

Individuals who effectively manage their finances tend to achieve a higher degree of financial security. This security can alleviate stress and anxiety related to monetary concerns, leading to a more content and satisfied life. Thus, the relationship between personal financial management and life satisfaction might be mediated by the sense of financial security and reduced monetary stress achieved through effective financial practices.

14. The Link Between Reading Habits and Vocabulary Size

Independent Variable: Reading habits Dependent Variable: Vocabulary size Mediating Variable: Exposure to diverse words and contexts

Individuals who read regularly encounter a wide variety of words in different contexts. This repeated exposure enhances their vocabulary as they come across and internalize new words. Therefore, the relationship between reading habits and vocabulary size might be mediated by the degree of exposure to diverse words and contexts through reading.

15. The Link Between Community Involvement and Personal Well-being

Independent Variable: Community involvement Dependent Variable: Personal well-being Mediating Variable: Sense of belonging and purpose

Engaging with and contributing to one’s community can foster a sense of belonging and purpose. Feeling connected and knowing that one’s actions positively impact others can lead to enhanced personal well-being. Thus, the relationship between community involvement and personal well-being might be mediated by the heightened sense of belonging and purpose derived from active community participation.

Mediating vs Moderating vs Confounding Variables

Mediating, moderating, and confounding variables are three of the most common types of ‘ third variable ‘. They are similar in that they need to be observed or controlled in order to better understand the relationship between the independent and dependent variables (Stapel & van Beek, 2015).

However, the three differ in important ways.

Let’s start with some definitions:

- Mediating Variables: These explain the process through which an independent variable influences a dependent variable.

- Moderating Variables : These influence the strength or direction of the relationship between an independent and a dependent variable (Nestor & Schutt, 2018).

- Confounding Variables : These are external factors that, if not controlled, can cause a false perception of a relationship between the independent and dependent variables (Boniface, 2019).

The table below shows how they differ:

| Aspect | Mediating Variables | Moderating Variables | Confounding Variables |

|---|---|---|---|

| Explains the process or mechanism through which the independent variable affects the dependent variable. | Affects the strength or direction of the relationship between the independent variable and dependent variable. | An external factor that is related to both the independent variable and dependent variable, potentially creating a false impression of a direct relationship between the two (Scharrer & Ramasubramanian, 2021). | |

| Helps clarify or one variable affects another. | Helps clarify or the independent variable affects the dependent variable differently. | Introduces bias or distortion in the observed relationship between independent variable and dependent variable if not controlled. | |

| Studying the effect of training on job performance, where self-confidence (mediator) increases with training and leads to better performance. | Studying the effect of training on job performance, where the relationship might be stronger for those with prior related experience (moderator). | When examining the relationship between exercise and health, diet (confounder) can influence both exercise habits and health, potentially distorting the observed relationship. |

Boniface, D. R. (2019). Experiment Design and Statistical Methods For Behavioural and Social Research . CRC Press. ISBN: 9781351449298.

Hefner, V. (2017). Variables, Moderating Types . In Allen, M. (Ed.) The SAGE Encyclopedia of Communication Research Methods . SAGE Publications.

Nestor, P. G., & Schutt, R. K. (2018). Research Methods in Psychology: Investigating Human Behavior . SAGE Publications.

Scharrer, E., & Ramasubramanian, S. (2021). Quantitative Research Methods in Communication: The Power of Numbers for Social Justice . Taylor & Francis.

Stapel, B. & van Beek, R.J. (2015). Confounders, moderators and mediators. In Mellenbergh, G. J., & Adèr, H. J. (Eds.). Advising on Research Methods: Selected Topics 2014 . Johannes van Kessel Advising.

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 25 Number Games for Kids (Free and Easy)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 25 Word Games for Kids (Free and Easy)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 25 Outdoor Games for Kids

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 50 Incentives to Give to Students

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Research Methods Course Pack

Chapter 10 moderating, mediating, and confounding variables, 10.1 more than the iv and the dv.

In this section, we’ll expand our understanding of variables in the study. So far, we have discussed three types of variables:

Independent variable (IV): The variable that is implied (quasi-experiment, non-experiment) or demonstrated to be (experiment) the cause of an effect. When there is a manipulation, the variable that is manipulated is the IV.

Dependent variable (DV): The variable that is implied or demonstrated to be the outcome.

Confounding variable: Also called a nuisance variable or third variable. This is a third variable that causes a change in both the IV and the DV at the same time. To borrow an example, we might observe a correlation between ice cream consumption and snake bites. We might wonder if eating ice cream causes snake bites on the basis of this result. Although this seems ridiculous, it’s easier for us to make these sorts of conclusions when the variables are psychological constructs (for example, personality and job outcomes). In this example, the weather is a confounding variable. When the weather is warmer, ice cream consumption (it’s warm) and snake bites (people go on hikes) increase.

From this example, you might wonder if other factors matter, such as the location (regions with lots of snakes versus regions with fewer). Some of these other variables may affect the DV in other ways, such as by weakening the relationship between the IV and the DV. Therefore, confounding variables are one type of extraneous variable. Extraneous variables include anything we have not included in our study.

Some extraneous variables are not likely to affect anything. In this example, the gender of people buying ice cream probably does not affect their likelihood of snake bites. Other extraneous variables can affect the relationship we are trying to observe in our study. Whenever you design a study, an important step is to stop and consider “what else could be affecting this relationship?” When you do this, you will brainstorm a list of possible confounding and extraneous variables. Then, you’ll decide if the variables are likely to affect the relationship of interest. If they are, then usually you can redesign your study to avoid them.

To summarize: A study is essentially a search to identify and explain relationships between IVs and DVs. When claims about the relationship between an IV and DV are true, the claim has internal validity.

Next, we will explore two more complex relationships between variables that develop when we add a second IV to our model.

10.2 Moderating Variables: Interaction Effects

Interactions are also called moderated relationships or moderation. An interaction occurs when the effect of one variable depends on the value of another variable. ** For example, how do you increase the sweetness of coffee? Imagine that sweetness is the DV, and the two variables are stirring (yes vs no) and adding a sugar cube (yes vs no).

We diagram a moderated relationship using this notation:

Diagram of a moderated relationship with IV 2 and IV 1 interacting to affect DV

And, when we have group means for every condition, we can see the impact of these two factors (factor is a fancy word for IV) in a table:

| . | Stirring: Yes | Stirring: No |

|---|---|---|

| Sugar: Yes | \(\bar{X}_{sweet}=100\) | \(\bar{X}_{sweet} = 0\) |

| Sugar: No | \(\bar{X}_{sweet}=0\) | \(\bar{X}_{sweet} = 0\) |

When is the coffee sweet? Stirring alone does not change the taste of the coffee. Adding a sugar cube alone also doesn’t change the taste of the coffee, since the sugar will just sink to the bottom. It’s only when sugar is added, and the coffee is stirred that it tastes sweet.

We can say there is an interaction between adding sugar and stirring coffee. The effect of the stirring depends on the value of another variable (whether or not sugar is added).

10.3 Some Terminology

When more than one IV is included in a model, we are using a factorial design. Factorial designs include 2 or more factors (or IVs) with 2 or more levels each. In the coffee example, our design has two factors (stirring and adding sugar), each with two levels.

In factorial designs (i.e., studies that manipulate two or more factors), participants are observed at each level of each factor. Because every possible combination of each IV is included, the effects of each factor alone can be observed. We also get to see how these factors impact each other. We say this design is fully crossed because every possible combination of levels is included.

10.4 Main Effects

A main effect is the effect of one factor. There is one potential main effect for each factor.

In this example, the potential main effects are stirring and adding sugar. To find the main effects, find the mean of each column (i.e., add the two numbers and divide by 2). If there are differences in these means, there is a significant main effect for one of the factors. Next, find the mean of each row (add going across and divide by 2). If there are differences in these row means, then there is a main effect for the other factor.

| . | Stirring: Yes | Stirring: No | Row mean |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sugar: Yes | \(\bar{X}_{sweet}=100\) | \(\bar{X}_{sweet} = 0\) | \(\bar{X}_{sugar}= 50\) |

| Sugar: No | \(\bar{X}_{sweet}=0\) | \(\bar{X}_{sweet} = 0\) | \(\bar{X}_{\text{no sugar}}=0\) |

| Column mean | \(\bar{X}_{stir}=50\) | \(\bar{X}_{nostir}=0\) . |

In our example, we see two main effects. Adding a sugar cube (mean of 50) differs from not adding sugar (mean of 0). That’s the first main effect. The second is stirring; stirring (mean of 50) differs from not stirring (mean of 0).

10.5 Simple Effects

When an interaction effect is present, each part of an interaction is called a simple effect. To examine the simple effects, compare each cell to every other cell in the same row. Next, compare each cell to ever other cell in the same column. Simple effects are never diagonal from each other.

In our example, we see a simple effect as we go from Stir+Sugar to NoStir+Sugar. There is no simple effect between Stir+NoSugar and NoStir+NoSugar (both are 0). What makes this an interaction effect is that these two simple effects are different from one another.

On the vertical, there is a simple effect from Stir+Sugar to Stir+NoSugar. There is no simple effect from NoStir+Sugar to NoStir+NoSugar (both are 0). Again, this is an interaction effect because these two simple effects are different.

10.6 Interaction Effect

When there is at least one (significant) simple effect that differs across levels of one of the IVs (as demonstrated above), then you can say there is an interaction between the two factors. In a two-way ANOVA, there is one possible interaction effect. We sometimes show this with a multiplication symbol: Sugar*Stir. In our example, there is an interaction between sugar and stirring.

In summary: An interaction effect is when the impact of one variable depends on the level of another variable.

Interaction effects are important in psychology because they let us explain the circumstances under which an effect occurs. Anytime we say that an effect depends on something else, we are describing an interaction effect.

10.7 Mediators and Mediated Relationships

A mediated relationship is a chain reaction; one variable causes another variable (the mediator), which then causes the DV. Please forgive another silly example; I am including it to keep the example as simple as possible. Here is how we diagram it:

This is a totally different situation that the previous one. The first variable is a preference for sweetness; do you like sweet foods and beverages? If participants prefer sweetness, then they will add more sugar. If they don’t prefer sugar in their coffee, then they will add less (or no) sugar. Thus, preference for sweetness is an IV that causes a change in the mediator, adding sugar. Finally, adding sugar is what causes the coffee to taste sweet. Any time we can string together three variables in a causal chain, we are describing a mediated relationship.

In summary: A mediated relationship occurs when one variable affects another (the mediator), and that variable (the mediator), affects something else.

Mediated relationships are important in psychology because they let us explain why or how an effect happens. The mediator is the how or the why. Why do participants who prefer sweetness end up with sweeter coffee? It is because they added sugar.

| |

| |

| you plan to discover it. If one variable truly causes a second, it . may be also called or . . Thus, a mediating or mediator variable is An hypothesis may describe a relationship exists, possible of the relationship ("null" hypotheses are directionless), (how) of the relationship; even of the relationship. (categories are different) (categories are ordered) (categories are numbers). Even a two category variable can be ordinal if we can rank the categories ("yes I smoked a cigarette" is more than "no I didn't"). |

| | |

| you plan to discover it. |

- cognitive sophistication

- tolerance of diversity

- exposure to higher levels of math or science

- age (which is currently related to educational level in many countries)

- social class and other variables.

- For example, suppose you designed a treatment to help people stop smoking. Because you are really dedicated, you assigned the same individuals simultaneously to (1) a "stop smoking" nicotine patch; (2) a "quit buddy"; and (3) a discussion support group. Compared with a group in which no intervention at all occurred, your experimental group now smokes 10 fewer cigarettes per day.

- There is no relationship among two or more variables (EXAMPLE: the correlation between educational level and income is zero)

- Or that two or more populations or subpopulations are essentially the same (EXAMPLE: women and men have the same average science knowledge scores.)

| |

| someone who favors raising teacher salaries obviously is more in favor than someone who opposes the raise. |

- the difference between two and three children = one child.

- the difference between eight and nine children also = one child.

- the difference between completing ninth grade and tenth grade is one year of school

- the difference between completing junior and senior year of college is one year of school

- In addition to all the properties of nominal, ordinal, and interval variables, ratio variables also have a fixed/non-arbitrary zero point. Non arbitrary means that it is impossible to go below a score of zero for that variable. For example, any bottom score on IQ or aptitude tests is created by human beings and not nature. On the other hand, scientists believe they have isolated an "absolute zero." You can't get colder than that.

In order to continue enjoying our site, we ask that you confirm your identity as a human. Thank you very much for your cooperation.

Baron & Kenny’s Procedures for Mediational Hypotheses

Mediational hypotheses are the kind of hypotheses in which it is assumed that the affect of an independent variable on a dependent variable is mediated by the process of a mediating variable and the independent variable may still affect the independent variable. In other words, in mediational hypothesis, the mediator variable is the intervening or the process variable. The mediational hypothesis assumes the complete mediation in the variables

The term complete mediation in mediational hypothesis means that the independent variable does not at all affect the dependent variable after the mediator variable has controlled it. The mediation model involved in mediational hypothesis is a causal model.

Baron & Kenny’s procedures describes the analyses which are required for testing various mediational hypothesis.

Discover How We Assist to Edit Your Dissertation Chapters

Aligning theoretical framework, gathering articles, synthesizing gaps, articulating a clear methodology and data plan, and writing about the theoretical and practical implications of your research are part of our comprehensive dissertation editing services.

- Bring dissertation editing expertise to chapters 1-5 in timely manner.

- Track all changes, then work with you to bring about scholarly writing.

- Ongoing support to address committee feedback, reducing revisions.

The first step involved in Baron & Kenny’s procedures is that the researcher must be shown that the initial variable is being correlated with the outcome variable. In other words, the first step in Baron & Kenny’s procedures involves the establishment of an effect which may be mediated.

The second step involved in Baron & Kenny’s procedures is that the researcher must be shown that the initial variable is being correlated with the mediator. In other words, the second step in Baron & Kenny’s procedures involves treating the mediator variable as an outcome variable.

The third step in Baron & Kenny’s procedures involves an establishment of the correlation between the mediator variable and the outcome variable. In this step of Baron & Kenny’s procedures, there exists correlation between the mediator and the outcome variable because they both are caused due to the initial variable. In other words, in Baron & Kenny’s procedures, the initial variable must be controlled while establishing the correlation between the two other variables.

The next step in Baron & Kenny’s procedures involves the establishment of the complete mediation across the variables. This establishment in the last step of Baron & Kenny’s procedures can only be achieved if the affect of the initial variable over the outcome variable while controlling for mediator variable is zero.

If all four steps of Baron & Kenny’s procedures are met, then the data is consistent with the mediational hypothesis. If, however, only the first three steps of Baron & Kenny’s procedures are satisfied, then partial mediation is observed in the data.

The researcher should keep in mind that if the steps involved in Baron & Kenny’s procedures are completely satisfied, it still does not imply that the mediation has occurred as there are other less plausible models that are consistent with the data.

The mediator variable in mediation hypothesis can be caused by the outcome variable. This happens when the initial variable is a manipulated variable—then it cannot be caused either by the mediator or the outcome in mediation hypothesis. However, since both the mediator and the outcome variables are not manipulated, they may cause each other in mediational hypothesis.

It is always sensible to swap the mediator variable and the outcome variable and have the outcome cause the mediator in mediational hypothesis.

Related Pages:

- Mediator Variable

Dr Martin Lea

- 5. Example of a Basic Test of Mediation

The simplest mediation analysis involves a single independent variable, a dependent variable, and a hypothesized mediator.

The unmediated model is represented by the direct effect of x on y, quantified as c.

However, the effect of X on Y may be mediated by a process, or mediating variable M.

Partial mediation is the case in which the path from X to Y is reduced in absolute size but is still different from zero when the mediator is controlled for.

In path analysis, an independent variable is called an exogenous variable. Any variable that is predicted by another variable acts as a dependent variable and is called an endogenous variable.

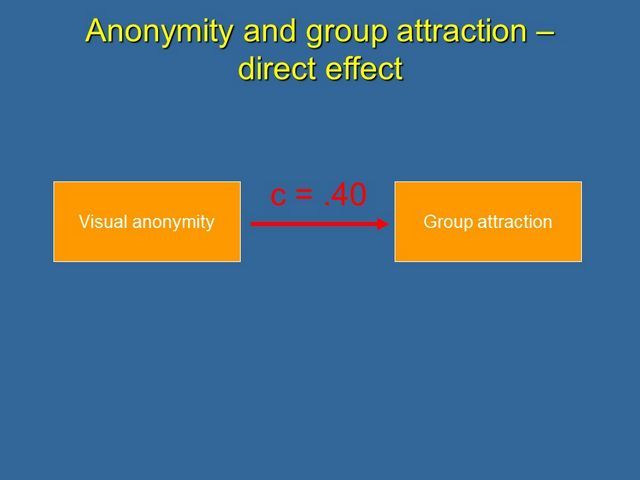

Example: Effects of visual anonymity on attraction to the group

Here's an example of a simple mediation analysis relating to my own research.

In this example I test some ideas about deindividuation theory that derive from a social identity approach to group behaviour.

My basic hypothesis was that visual anonymity among group members increases attraction to the group.

I test this by regressing group attraction onto a measure of visual anonymity, and found that visual anonymity significantly affected group attraction with a Beta of .40.

However, I also hypothesized that this effect was mediated by the extent to which group members perceived or categorized themselves as part of the group – a self-categorization variable. I next test this mediated effect and measure the change in the direct effect, with the following results….

As you can see from the path diagram, visual anonymity had an effect on self-categorization, which in turn had an effect on group attraction. At the same time, the direct effect of anonymity on group attraction (which was previously .50) is now reduced to just about zero, after the mediated effect is taken into account. In other words the hypothesized mediated effect accounted for just about all of the effect of anonymity on group attraction.

Note that self-categorization is considered here to be a mediator, not a moderator. That is, my model was not that visual anonymity increases group attraction when group members self-categorize as part of the group.

Instead, my model was that anonymity increases group attraction because it increased self-categorization.

In other words, my model addressed how and why anonymity achieves its effect, not when it achieves its effect.

NEXT: 6. Mediation Analysis: Procedures and Tests

Statistics Training: Introduction to Path Analysis

- 9. Causal Steps to Establish Mediation: Steps 3 & 4

- 8. Causal Steps to Establish Mediation: Step 2

- 7. Causal Steps to Establish Mediation: Step 1

- 6. Mediation Analysis: Procedures and Tests

- 4. Example of the Difference between Moderation and Mediation

- 3. Moderation and Mediation Explained

- 2. A Quick Review of Regression

- 13. Sobel's Test of Significant Mediation

- 12. Testing for Significant Mediation

- 11. An Example of a Mediator Acting as a Suppressor

- 10. Barron and Kenny (1986) Criteria for Mediation

- 1. What is Path Analysis?

If you found this article useful, please share so others can find it.

I was an academic researcher before starting my Academic Web Design business in 2013. I build WordPress websites exclusively for researchers, authors, educators, and therapists. View my Portolio or read my Guides to creating an academic website.

Download My Disaster Resources

Enter Your email to access and download

- Full-text articles and Full length reports (PDF)

- Reference lists and Endnote Bibliographies

- Survey items and Questionnaires

- Checklists and Recommendations

Get notified about new resources when I add them

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Advance articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About Biostatistics

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

- < Previous

DP2LM: leveraging deep learning approach for estimation and hypothesis testing on mediation effects with high-dimensional mediators and complex confounders

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Shuoyang Wang, Yuan Huang, DP2LM: leveraging deep learning approach for estimation and hypothesis testing on mediation effects with high-dimensional mediators and complex confounders, Biostatistics , Volume 25, Issue 3, July 2024, Pages 818–832, https://doi.org/10.1093/biostatistics/kxad037

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Traditional linear mediation analysis has inherent limitations when it comes to handling high-dimensional mediators. Particularly, accurately estimating and rigorously inferring mediation effects is challenging, primarily due to the intertwined nature of the mediator selection issue. Despite recent developments, the existing methods are inadequate for addressing the complex relationships introduced by confounders. To tackle these challenges, we propose a novel approach called DP2LM (Deep neural network-based Penalized Partially Linear Mediation). This approach incorporates deep neural network techniques to account for nonlinear effects in confounders and utilizes the penalized partially linear model to accommodate high dimensionality. Unlike most existing works that concentrate on mediator selection, our method prioritizes estimation and inference on mediation effects. Specifically, we develop test procedures for testing the direct and indirect mediation effects. Theoretical analysis shows that the tests maintain the Type-I error rate. In simulation studies, DP2LM demonstrates its superior performance as a modeling tool for complex data, outperforming existing approaches in a wide range of settings and providing reliable estimation and inference in scenarios involving a considerable number of mediators. Further, we apply DP2LM to investigate the mediation effect of DNA methylation on cortisol stress reactivity in individuals who experienced childhood trauma, uncovering new insights through a comprehensive analysis.

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Short-term Access

To purchase short-term access, please sign in to your personal account above.

Don't already have a personal account? Register

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| February 2024 | 82 |

| March 2024 | 37 |

| April 2024 | 47 |

| May 2024 | 44 |

| June 2024 | 28 |

| July 2024 | 34 |

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Biostatistics Blog

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1468-4357

- Print ISSN 1465-4644

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

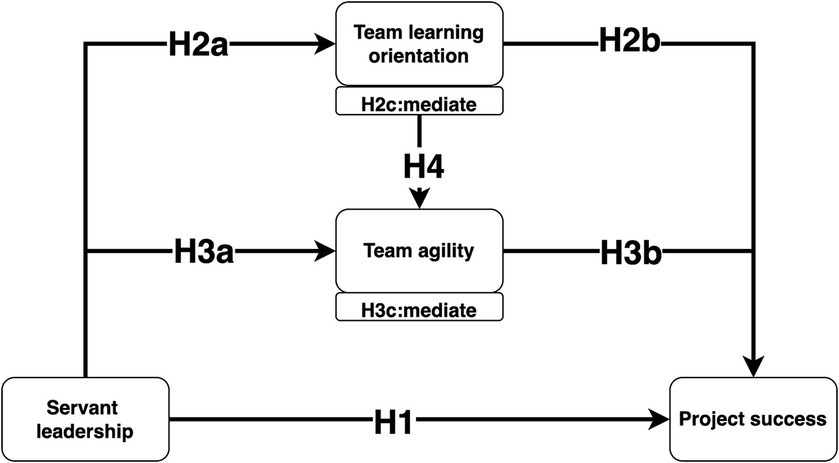

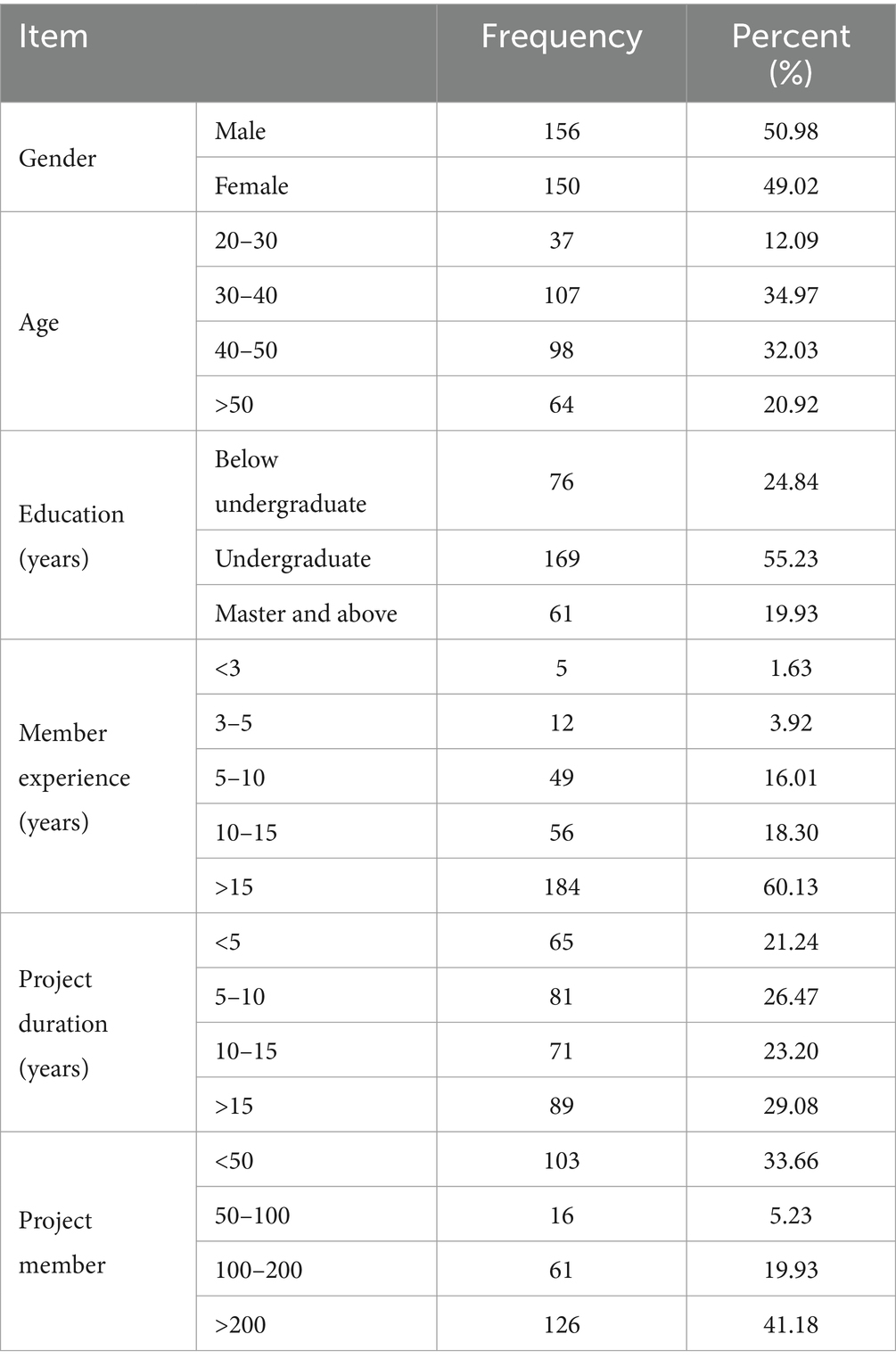

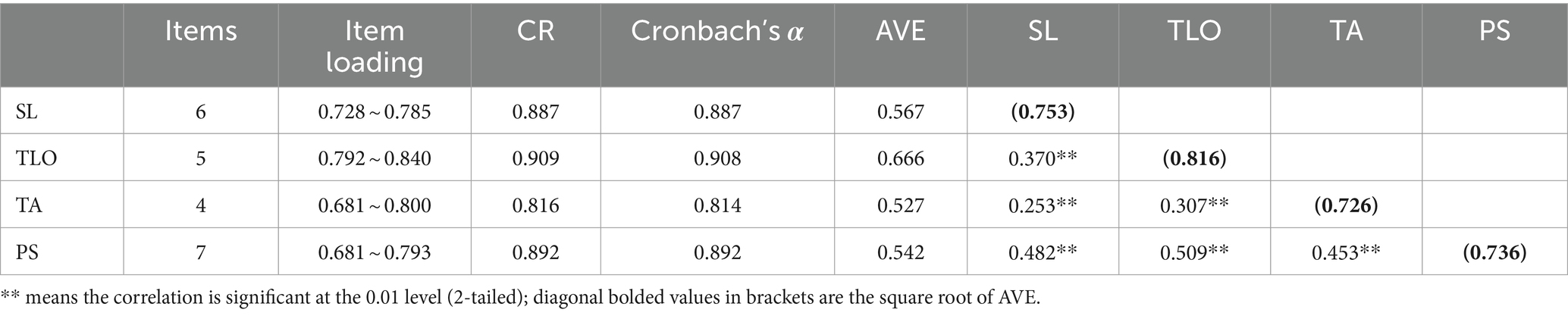

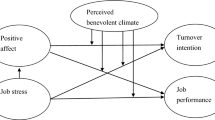

Servant leadership and project success: the mediating roles of team learning orientation and team agility.

- 1 School of Economics and Management, Liaoning University of Technology, Jinzhou, Liaoning, China

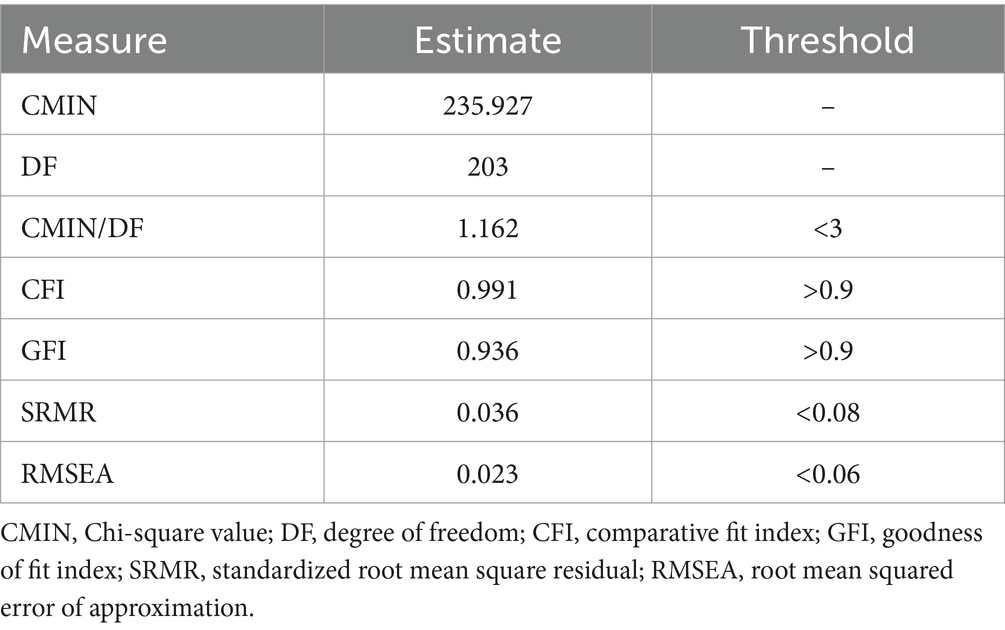

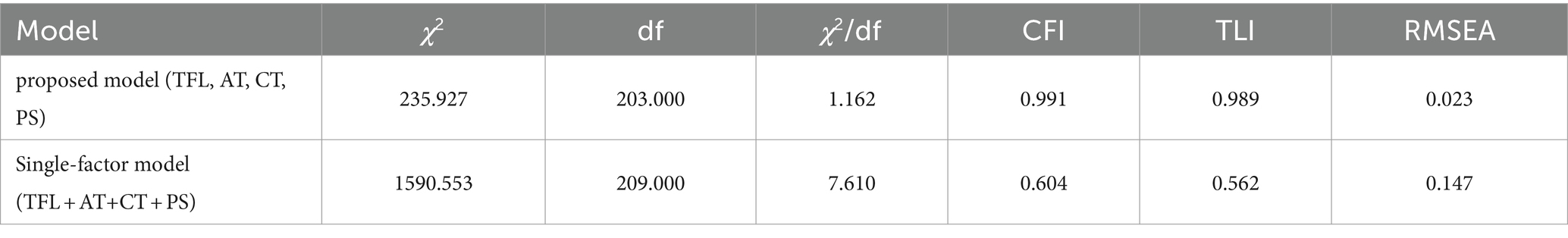

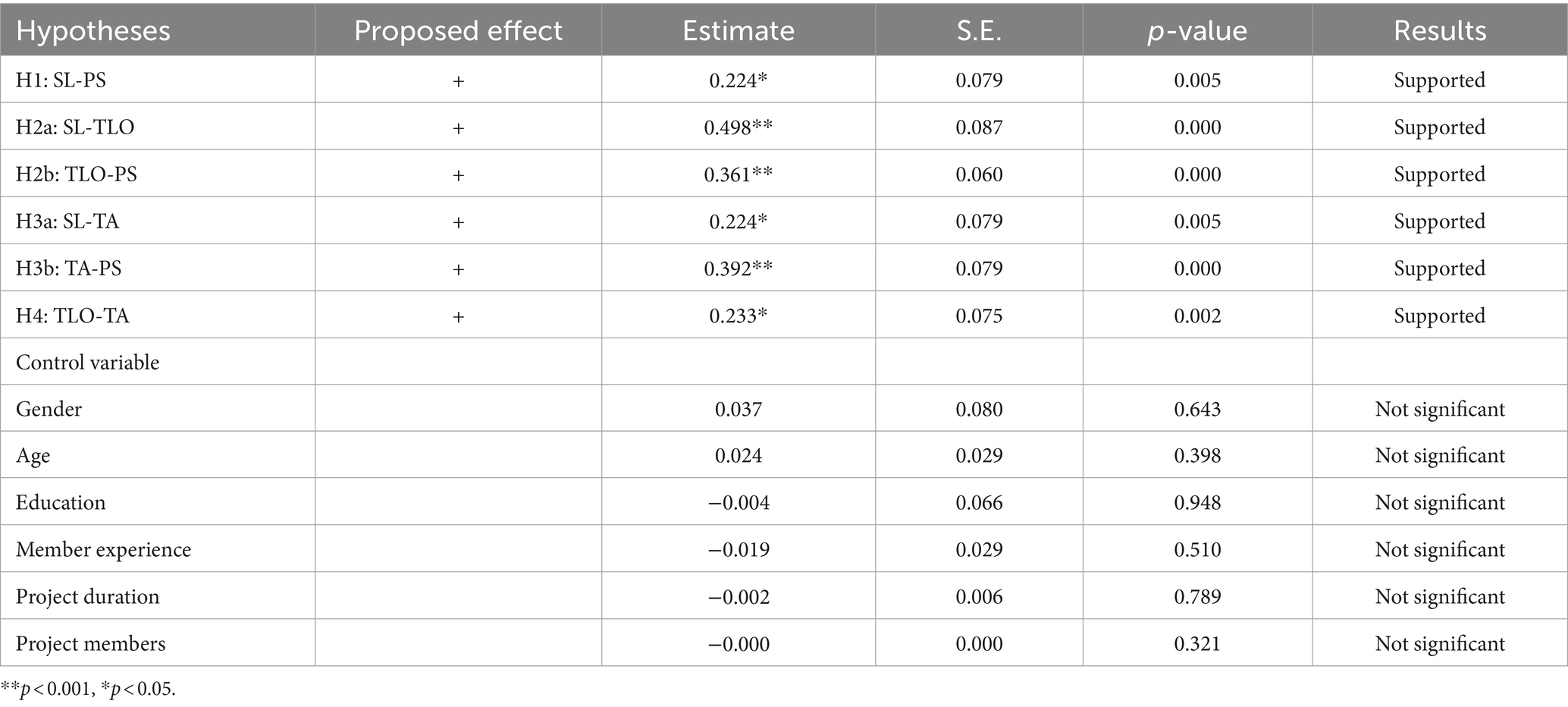

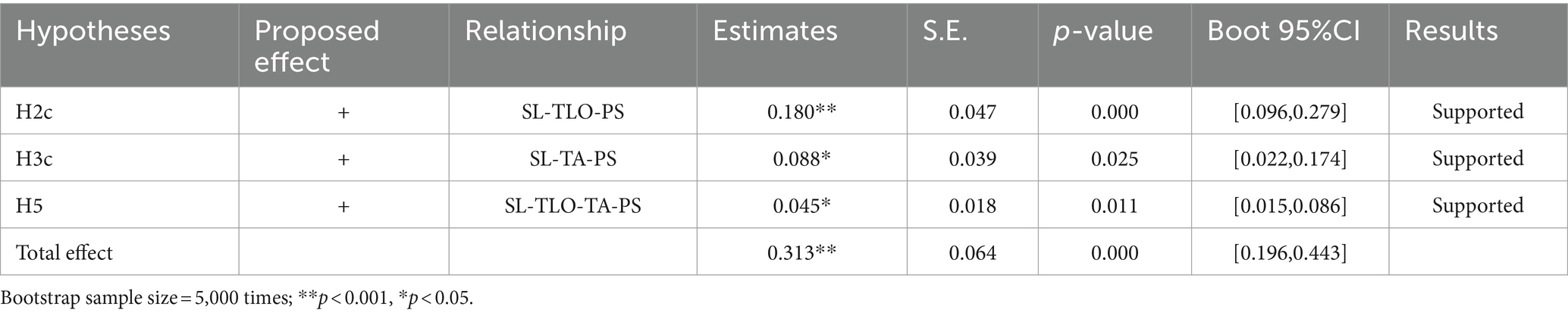

- 2 SolBridge International School of Business, Woosong University, Daejeon, Republic of Korea