- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction & Top Questions

Early life and training

- Screen memories

- The interpretation of dreams

- Further theoretical development

- Sexuality and development

- Toward a general theory

- Religion, civilization, and discontents

Where was Sigmund Freud educated?

What did sigmund freud die of, why is sigmund freud famous.

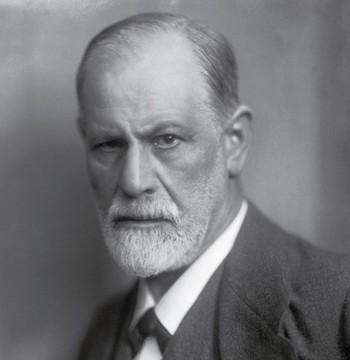

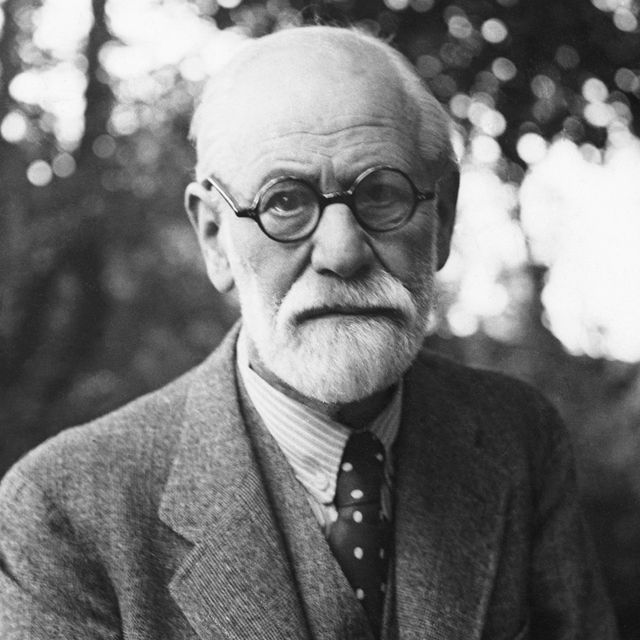

Sigmund Freud

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Simply Psychology - Sigmund Freud's Theories

- British Psychological Society - Sigmund Freud and penis envy – a failure of courage?

- Good Therapy - Sigmund Freud

- Famous Scientists - Sigmund Freud

- Institute of Psychoanalysis - Sigmund Freud

- Public Broadcasting Service - People and Discoveries - Biography of Sigmund Freud

- Social Science LibreTexts - A Brief Biography of Sigmund Freud, M.D.

- Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy - Biography of Sigmund Freud

- Sigmund Freud - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- Sigmund Freud - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

After graduating (1873) from secondary school in Vienna, Sigmund Freud entered the medical school of the University of Vienna , concentrating on physiology and neurology ; he obtained a medical degree in 1881. He trained (1882–85) as a clinical assistant at the General Hospital in Vienna and studied (1885–86) in Paris under neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot .

Sigmund Freud died of a lethal dose of morphine administered at his request by his friend and physician Max Schur. Freud had been suffering agonizing pain caused by an inoperable cancerous tumour in his eye socket and cheek. The cancer had begun as a lesion in his mouth that he discovered in 1923.

What did Sigmund Freud write?

Sigmund Freud’s voluminous writings included The Interpretation of Dreams (1899/1900), The Psychopathology of Everyday Life (1904), Totem and Taboo (1913), and Civilization and Its Discontents (1930).

Freud is famous for inventing and developing the technique of psychoanalysis ; for articulating the psychoanalytic theory of motivation, mental illness , and the structure of the subconscious ; and for influencing scientific and popular conceptions of human nature by positing that both normal and abnormal thought and behaviour are guided by irrational and largely hidden forces.

Sigmund Freud (born May 6, 1856, Freiberg, Moravia , Austrian Empire [now Příbor, Czech Republic]—died September 23, 1939, London , England) was an Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis .

(Read Sigmund Freud’s 1926 Britannica essay on psychoanalysis.)

Freud may justly be called the most influential intellectual legislator of his age. His creation of psychoanalysis was at once a theory of the human psyche, a therapy for the relief of its ills, and an optic for the interpretation of culture and society. Despite repeated criticisms , attempted refutations, and qualifications of Freud’s work, its spell remained powerful well after his death and in fields far removed from psychology as it is narrowly defined. If, as American sociologist Philip Rieff once contended, “psychological man” replaced such earlier notions as political, religious, or economic man as the 20th century’s dominant self-image, it is in no small measure due to the power of Freud’s vision and the seeming inexhaustibility of the intellectual legacy he left behind.

Freud’s father, Jakob, was a Jewish wool merchant who had been married once before he wed the boy’s mother, Amalie Nathansohn. The father, 40 years old at Freud’s birth , seems to have been a relatively remote and authoritarian figure, while his mother appears to have been more nurturant and emotionally available. Although Freud had two older half-brothers, his strongest if also most ambivalent attachment seems to have been to a nephew, John, one year his senior, who provided the model of intimate friend and hated rival that Freud reproduced often at later stages of his life.

In 1859 the Freud family was compelled for economic reasons to move to Leipzig and then a year after to Vienna , where Freud remained until the Nazi annexation of Austria 78 years later. Despite Freud’s dislike of the imperial city , in part because of its citizens’ frequent anti-Semitism , psychoanalysis reflected in significant ways the cultural and political context out of which it emerged. For example, Freud’s sensitivity to the vulnerability of paternal authority within the psyche may well have been stimulated by the decline in power suffered by his father’s generation, often liberal rationalists, in the Habsburg empire. So too his interest in the theme of the seduction of daughters was rooted in complicated ways in the context of Viennese attitudes toward female sexuality .

In 1873 Freud was graduated from the Sperl Gymnasium and, apparently inspired by a public reading of an essay by Goethe on nature, turned to medicine as a career. At the University of Vienna he worked with one of the leading physiologists of his day, Ernst von Brücke , an exponent of the materialist, antivitalist science of Hermann von Helmholtz . In 1882 he entered the General Hospital in Vienna as a clinical assistant to train with the psychiatrist Theodor Meynert and the professor of internal medicine Hermann Nothnagel. In 1885 Freud was appointed lecturer in neuropathology, having concluded important research on the brain ’s medulla . At this time he also developed an interest in the pharmaceutical benefits of cocaine , which he pursued for several years. Although some beneficial results were found in eye surgery, which have been credited to Freud’s friend Carl Koller , the general outcome was disastrous. Not only did Freud’s advocacy lead to a mortal addiction in another close friend, Ernst Fleischl von Marxow, but it also tarnished his medical reputation for a time. Whether or not one interprets this episode in terms that call into question Freud’s prudence as a scientist, it was of a piece with his lifelong willingness to attempt bold solutions to relieve human suffering.

Freud’s scientific training remained of cardinal importance in his work, or at least in his own conception of it. In such writings as his “Entwurf einer Psychologie” (written 1895, published 1950; “Project for a Scientific Psychology”) he affirmed his intention to find a physiological and materialist basis for his theories of the psyche. Here a mechanistic neurophysiological model vied with a more organismic, phylogenetic one in ways that demonstrate Freud’s complicated debt to the science of his day.

In late 1885 Freud left Vienna to continue his studies of neuropathology at the Salpêtrière clinic in Paris, where he worked under the guidance of Jean-Martin Charcot . His 19 weeks in the French capital proved a turning point in his career, for Charcot’s work with patients classified as “ hysterics ” introduced Freud to the possibility that psychological disorders might have their source in the mind rather than the brain. Charcot’s demonstration of a link between hysterical symptoms, such as paralysis of a limb, and hypnotic suggestion implied the power of mental states rather than nerves in the etiology of disease . Although Freud was soon to abandon his faith in hypnosis , he returned to Vienna in February 1886 with the seed of his revolutionary psychological method implanted.

Several months after his return Freud married Martha Bernays, the daughter of a prominent Jewish family whose ancestors included a chief rabbi of Hamburg and Heinrich Heine . She was to bear six children, one of whom, Anna Freud , was to become a distinguished psychoanalyst in her own right. Although the glowing picture of their marriage painted by Ernest Jones in his study The Life and Works of Sigmund Freud (1953–57) has been nuanced by later scholars, it is clear that Martha Bernays Freud was a deeply sustaining presence during her husband’s tumultuous career.

Shortly after getting married Freud began his closest friendship, with the Berlin physician Wilhelm Fliess, whose role in the development of psychoanalysis has occasioned widespread debate. Throughout the 15 years of their intimacy Fliess provided Freud an invaluable interlocutor for his most daring ideas. Freud’s belief in human bisexuality , his idea of erotogenic zones on the body, and perhaps even his imputation of sexuality to infants may well have been stimulated by their friendship.

A somewhat less controversial influence arose from the partnership Freud began with the physician Josef Breuer after his return from Paris. Freud turned to a clinical practice in neuropsychology , and the office he established at Berggasse 19 was to remain his consulting room for almost half a century. Before their collaboration began, during the early 1880s, Breuer had treated a patient named Bertha Pappenheim —or “Anna O.,” as she became known in the literature—who was suffering from a variety of hysterical symptoms. Rather than using hypnotic suggestion, as had Charcot, Breuer allowed her to lapse into a state resembling autohypnosis, in which she would talk about the initial manifestations of her symptoms. To Breuer’s surprise, the very act of verbalization seemed to provide some relief from their hold over her (although later scholarship has cast doubt on its permanence). “The talking cure” or “chimney sweeping,” as Breuer and Anna O., respectively, called it, seemed to act cathartically to produce an abreaction, or discharge, of the pent-up emotional blockage at the root of the pathological behaviour.

The mind is like an iceberg, it floats with one-seventh of its bulk above water.

- By Sigmund Freud

Sigmund Freud - The Father of Psychoanalysis

A renowned psychologist, physiologist and great thinker during the early 20th century, Sigmund Freud is referred to as the father of psychoanalysis. He formulated several theories throughout his lifetime including the concepts of infantile sexuality, repression and the unconscious mind. Freud also explored on the structure of the mind, and developed a therapeutic framework that intends to understand and treat disturbing mental issues. Freud's aim was to establish a 'scientific psychology' and his wish was to achieve this by applying to psychology the same principles of causality as were at that that time considered valid in physics and chemistry. With the scope of his studies and impact of his theories on the modern world's concept of psychoanalysis, it is evident that much of these principles are rooted from the original works of Freud, although his theories have often become the subject of controversy among scholars.

Sigmund Freud was born in Moravia, but he was raised in Vienna and lived there until his death. As a student, he was deeply interested in psychoanalysis, although he also considered himself a scientist. In 1873, he took up biology at the University of Vienna while undertaking research work in physiology. His mentor was Ernst Brcke, a German scientist who was also the director of the university's physiology laboratory.

In 1881, Freud obtained a degree in medicine, which equipped him with credentials that enabled him to find employment as a doctor at the Vienna General Hospital. However, he became more interested in treating psychological disorders, so he decided to pursue a private practice that focused on this field.

The voice of the intellect is a soft one, but it does not rest until it has gained a hearing." - Quote by Sigmund Freud

During his travel to Paris, he gained much knowledge on the work and theories of Jean Charcot, who was a French neurologist. Charcot performed hypnotism in treating abnormal mental problems including hysteria. This inspired Freud to use the same technique, although he eventually discovered the fleeting effects of hypnosis on the treatment of mental conditions. Thus, he experimented on other techniques such as the one proposed by Josef Breuer, one of Freud's collegaues.

The method involved encouraging patients to talk about any symptoms they experience since Breuer believed that trauma is usually rooted from past instances stuck in a person's unconscious mind. By allowing patients to discuss their symptoms uninhibitedly, they are able to confont these issues in an emotional and intellectual manner. The theory behind this technique was published in 1895, and it was entitled Studies in Hysteria .

Freud's psychoanalytic theory was rather controversial, and several scholars did not agree with his preoccupation on the topic of sexuality. It was only in 1908 when this theory by Freud was recognized by critics, specifically during the first International Psychoanalytic Congress in Salzburg. He also received an invitation to the United States, so he could conduct lectures on his psychoanalytic theory. This inspired him to go deeper into is studies, and he was able to produce over 20 volumes of his clinical studies and theoretical works. Fredu also developed the model of the mind as presented in The Ego and the Id , which was his scholarly work in 1923. Several scientists were inspired by Freud's theories including Jung and Adler, to name a few.

What progress we are making. In the Middle Ages they would have burned me. Now they are content with burning my books." - Quote by Sigmund Freud

A Look on Sigmund Freud's Theories

While Sigmund Freud was an original thinker, his theories and studies were influenced by the works of other scholars including Breuer and Charcot. However, Freud developed his own scientific studies that were different from the theories of his colleagues. In fact, much of his concepts were rooted from his past such as in his work entitled The Interpretation of Dreams . Here, he delved into the emotional crisis he went through during his father's death, as well as his battles with dreams that occurred to him in his earlier years. He underwent a contrasting feelings of hate/shame and love/admiration towards his father. Freud also admitted that deep down, he had fantasies in which he secretly wished for his father to die as he viewed him as his rival for the affection of his mother, and it was one of his bases for the Oedipus Complex theory.

Sigmund Freud's Theory of Unconscious

Sigmund Freud believed that neuroses and other abnormal mental conditions are rooted from one's unconscious mind. However, these issues are slowly revealed through various means such as obsessive behavior, slips of the tongue and dreams. His theory was to go deeper into the underlying cause that produce these problems, wich can be accomplished by inspecting the conscious mind that is impacted by one's unconscious.

Freud also worked on the analysis of drives or instincts and how these arise in each person. According to him, there are two main categories of insticts such as Eros or life instict and Thanatos or death instinct. The former included instincts that are erotic and self-preserving while the latter was involved in drives that lead to cruelty and self-destruction. Thus, human actions are not purely rooted from motivations that are sexual in nature since death instincts barely involve sexuality as the motivating factor.

Infantile Sexuality

The theory of infantile sexuality by Sigmund Freud was influenced by Breuer's concept that traumatic events during one's childhood years can greatly impact adulthood. In addition, Freud claimed that the desire for sexual pleasure had its early beginnings during infancy as babies gain pleasure from sucking. He referred to this as the oral stage of development, which is followed by the anal stage, where the latter is involved in the energy release through the anus. Afterwards, a young child begins to experience an interest in the genitals during the phallic stage, as well as a sexual attraction for parent of the opposite sex. Lastly, the latency period is the stage of life when sexual desires are less pronounced, and it may end during the puberty period.

Freud believed that unresolved conflicts during childhood can negatively impact mental health once a person reaches adulthood. For instance, homosexuality was viewed as the result of issues linked with the Oedipus Complex, which remained unaddressed. It was also the product of a child's inability to identify with his or her parent of the same sex.

Structure of the Mind

Sigmund Freud claimed that the mind had three structural elements that included the id, ego and the super-ego. It was the id that involved instinctual sexual instincts, which must be satisfied. The ego is one's conscious self while the super-ego involved the conscience. Considering these structural components of the mind, it is important to understand it as a dynamic energy system. To achieve mental well-being, it is important that all of these elements are in harmony with each other. Otherwise, psychological problems may occur including neurosis due to repression, regression, sublimation and fixation.

Psychoanalysis as Clinical Treatment of Neuroses

The main concept behind psychoanalysis is to address and resolve any issues that arise due to lack of harmony with the three structural elements of the mind. The primary technique mainly involved a psychoanalyst who encourages the person to talk freely about his or her symptoms, fantasies and tendencies. Hence, psychoanalytic therapy is geared towards attaining self-understanding as the patient becomes more capable of determining and handling unconscious forces that may either motivate or fear him or her. Any pent-up or restricted psychic energy is released, which also helped resolve mental illnesses. However, there are some questions in terms of the effectiveness of this technique, as it remains open to debate and controversies among scholars.

Evaluation of Sigmund Freud and His Theories

Sigmund Freud viewed psychoanalysis as a new science that must be explored to address issues affecting the mind and psychological problems. However, several scholars argue that for a scientific theory to be considered as valid, it must be testable and incompatible with any possible observations. There is also the questionable aspect of Freud's theories and their coherence (or lack of it). While his theory provides entities, there is an absence of correspondence rules, which means they are impossible to be identified unless referenced to the behavior that is believed to be the cause of the problem.

Dreams are often most profound when they seem the most crazy." - Quote by Sigmund Freud

Since Freud's theory is likely to be unscientific, it is impossible to provide a solid basis for the treatment of mental illness when implementing psychoanalysis as therapy. On the other hand, there are some true and genuine theories that can result to negative results when applied inappropriately. The main issue here is the fact that it may be difficult to determine a specific treatment for neurotic illnesses by merely alleviating symptoms. However, the effectiveness of a particular treatment method can be determined by grouping patients and analyzing which ones are cured using a specific technique or those who did not obtain any treatment at all. Unfortunately, with the case of psychoanalysis as a treatment methodology, the number of patients who benefited from it was not significantly high, as compared to the percentage of individuals who were cured using other means of intervention. Therefore the effectiveness of Freud's psychoanalysis as treatment remains as a controversial and debatable topic.

More than a century has passed since Freud began to use his personal term "psychoanalysis", to describe what was at once his mode of therapy and his developing theory of the mind. We live more than ever in the Age of Freud, despite the relative decline that psychoanalysis has begun to suffer as a public institution and as a medical specialty. Freud's universal and comprehensive theory of the mind probably will outlive the psychoanalytical therapy, and seems already to have placed him with greatest thinkers Charles Darwin and William Shakespeare rather with the scientists he overtly aspired to emulate.

Sigmund Freud’s Theories & Contribution to Psychology

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Sigmund Freud (1856 to 1939) was the founding father of psychoanalysis , a method for treating mental illness and a theory explaining human behavior.

Freud believed that events in our childhood have a great influence on our adult lives, shaping our personality. For example, anxiety originating from traumatic experiences in a person’s past is hidden from consciousness and may cause problems during adulthood (neuroses).

Thus, when we explain our behavior to ourselves or others (conscious mental activity), we rarely give a true account of our motivation. This is not because we are deliberately lying. While human beings are great deceivers of others; they are even more adept at self-deception.

Freud’s life work was dominated by his attempts to penetrate this often subtle and elaborate camouflage that obscures the hidden structure and processes of personality.

His lexicon has become embedded within the vocabulary of Western society. Words he introduced through his theories are now used by everyday people, such as anal (personality), libido, denial, repression, cathartic, Freudian slip , and neurotic.

Who is Sigmund Freud

Sigmund Freud, born on May 6, 1856, in what is now Příbor, Czech Republic (then part of the Austrian Empire), is hailed as the father of psychoanalysis. He was the eldest of eight children in a Jewish family.

Freud initially wanted to become a law professional but later developed an interest in medicine. He entered the University of Vienna in 1873, graduating with an MD in 1881. His primary interests included neurology and neuropathology. He was particularly interested in the condition of hysteria and its psychological causes.

In 1885, Freud received a grant to study with Jean-Martin Charcot, a renowned neurologist who used hypnosis to treat women suffering from what was then called “hysteria.” This experience sparked Freud’s interest in the unconscious mind, a theme that would recur throughout his career.

In 1886, Freud returned to Vienna, married Martha Bernays, and set up a private practice to treat nervous disorders. His work during this time led to his revolutionary concepts of the human mind and the development of the psychoanalytic method.

Freud introduced several influential concepts, including the Oedipus complex, dream analysis, and the structural model of the psyche divided into the id, ego, and superego. He published numerous works throughout his career, the most notable being “ The Interpretation of Dreams ” (1900), “ The Psychopathology of Everyday Life ” (1901), and “ Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality ” (1905).

Despite controversy and opposition, Freud continued to develop his theories and expand the field of psychoanalysis. He was deeply affected by the outbreak of World War I and later by the rise of the Nazis in Germany. In 1938, due to the Nazi threat, he emigrated to London with his wife and youngest daughter.

Freud died in London on September 23, 1939, but his influence on psychology, literature, and culture remains profound and pervasive.

He radically changed our understanding of the human mind, emphasizing the power of unconscious processes and pioneering therapeutic techniques that continue to be used today.

Sigmund Freud’s Theories & Contributions

Psychoanalytic Theory : Freud is best known for developing psychoanalysis , a therapeutic technique for treating mental health disorders by exploring unconscious thoughts and feelings.

Unconscious Mind : Freud (1900, 1905) developed a topographical model of the mind, describing the features of the mind’s structure and function. Freud used the analogy of an iceberg to describe the three levels of the mind.

The id, ego, and superego have most commonly been conceptualized as three essential parts of the human personality.

Psychosexual Development : Freud’s controversial theory of psychosexual development suggests that early childhood experiences and stages (oral, anal, phallic, latency, and genital) shape our adult personality and behavior.

His theory of psychosexual stages of development is predicated by the concept that childhood experiences create the adult personality and that problems in early life would come back to haunt the individual as a mental illness.

Dream Analysis : Freud believed dreams were a window into the unconscious mind and developed methods for analyzing dream content for repressed thoughts and desires.

Dreams represent unfulfilled wishes from the id, trying to break through to the conscious. But because these desires are often unacceptable, they are disguised or censored using such defenses as symbolism.

Freud believed that by undoing the dreamwork , the analyst could study the manifest content (what they dreamt) and interpret the latent content ( what it meant) by understanding the symbols.

Defense Mechanisms : Freud proposed several defense mechanisms , like repression and projection, which the ego employs to handle the tension and conflicts among the id, superego, and the demands of reality.

Sigmund Freud’s Patients

Sigmund Freud’s clinical work with several patients led to major breakthroughs in psychoanalysis and a deeper understanding of the human mind. Here are summaries of some of his most notable cases:

Anna O. (Bertha Pappenheim) : Known as the ‘birth of psychoanalysis,’ Anna O . was a patient of Freud’s colleague Josef Breuer. However, her case heavily influenced Freud’s thinking.

She suffered from various symptoms, including hallucinations and paralysis, which Freud interpreted as signs of hysteria caused by repressed traumatic memories. The “talking cure” method with Anna O. would later evolve into Freudian psychoanalysis.

Dora (Ida Bauer) : Dora, a pseudonym Freud used, was a teenager suffering from what he diagnosed as hysteria. Her symptoms included aphonia (loss of voice) and a cough.

Freud suggested her issues were due to suppressed sexual desires, particularly those resulting from a complex series of relationships in her family. The Dora case is famous for the subject’s abrupt termination of therapy, and for the criticisms Freud received regarding his handling of the case.

Little Hans (Herbert Graf) : Little Hans , a five-year-old boy, feared horses. Freud never met Hans but used information from the boy’s father to diagnose him.

He proposed that Little Hans’ horse phobia was symbolic of a deeper fear related to the Oedipus Complex – unconscious feelings of affection for his mother and rivalry with his father. The case of Little Hans is often used as an example of Freud’s theory of the Oedipal Complex in children.

Rat Man (Ernst Lanzer) : Rat Man came to Freud suffering from obsessive thoughts and fears related to rats, a condition known as obsessional neurosis.

Freud connected his symptoms to suppressed guilt and repressed sexual desires. The treatment of Rat Man further expanded Freud’s work on understanding the role of internal conflicts and unconscious processes in mental health disorders.

Wolf Man (Sergei Pankejeff) : Wolf Man was a wealthy Russian aristocrat who came to Freud with various symptoms, including a recurring dream about wolves.

Freud’s analysis, focusing on childhood memories and dreams, led him to identify the presence of repressed memories and the influence of the Oedipus Complex . Wolf Man’s treatment is often considered one of Freud’s most significant and controversial cases.

In the highly repressive “Victorian” society in which Freud lived and worked, women, in particular, were forced to repress their sexual needs. In many cases, the result was some form of neurotic illness.

Freud sought to understand the nature and variety of these illnesses by retracing the sexual history of his patients. This was not primarily an investigation of sexual experiences as such. Far more important were the patient’s wishes and desires, their experience of love, hate, shame, guilt, and fear – and how they handled these powerful emotions.

Freud’s Followers

Freud attracted many followers, who formed a famous group in 1902 called the “Psychological Wednesday Society.” The group met every Wednesday in Freud’s waiting room.

As the organization grew, Freud established an inner circle of devoted followers, the so-called “Committee” (including Sàndor Ferenczi, and Hanns Sachs (standing) Otto Rank, Karl Abraham, Max Eitingon, and Ernest Jones).

At the beginning of 1908, the committee had 22 members and was renamed the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society.

Neo-Freudians

The term “neo-Freudians” refers to psychologists who were initially followers of Sigmund Freud (1856 to 1939) but later developed their own theories, often modifying or challenging Freud’s ideas.

Here are summaries of some of the most notable neo-Freudians:

Carl Jung : Jung (1875 – 1961) was a close associate of Freud but split due to theoretical disagreements. He developed the concept of analytical psychology, emphasizing the collective unconscious, which houses universal symbols or archetypes shared by all human beings. He also introduced the idea of introversion and extraversion.

Alfred Adler : Adler (1870 – 1937) was another early follower of Freud who broke away due to differing views. He developed the school of individual psychology, highlighting the role of feelings of inferiority and the striving for superiority or success in shaping human behavior. He also emphasized the importance of social context and community.

- Otto Rank : Rank (1884 – 1939) was an early collaborator with Freud and played a significant role in the development of psychoanalysis. He proposed the “trauma of birth” as a critical event influencing the psyche. Later, he shifted focus to the relationship between therapist and client, influencing the development of humanistic therapies.

Karen Horney : Horney (1885 – 1952) challenged Freud’s views on women, arguing against the concept of “penis envy.” She suggested that social and cultural factors significantly influence personality development and mental health. Her concept of ‘basic anxiety’ centered on feelings of helplessness and insecurity in childhood, shaping adult behavior.

- Harry Stack Sullivan : Sullivan (1892 – 1949) developed interpersonal psychoanalysis, emphasizing the role of interpersonal relationships and social experiences in personality development and mental disorders. He proposed the concept of the “self-system” formed through experiences of approval and disapproval during childhood.

Melanie Klein : Klein (1882 – 1960), a prominent psychoanalyst, is considered a neo-Freudian due to her development of object relations theory, which expanded on Freud’s ideas. She emphasized the significance of early childhood experiences and the role of the mother-child relationship in psychological development.

- Anna Freud : Freud’s youngest daughter significantly contributed to psychoanalysis, particularly in child psychology. Anna Freud (1895 – 1982) expanded on her father’s work, emphasizing the importance of ego defenses in managing conflict and preserving mental health.

Wilhelm Reich : Reich (1897 – 1957), once a student of Freud, diverged by focusing on bodily experiences and sexual repression, developing the theory of orgone energy. His emphasis on societal influence and body-oriented therapy made him a significant neo-Freudian figure.

- Erich Fromm : Fromm (1900-1980) was a German-American psychoanalyst associated with the Frankfurt School, who emphasized culture’s role in developing personality. He advocated psychoanalysis as a tool for curing cultural problems and thus reducing mental illness.

Erik Erikson : Erikson (1902 – 1994) extended Freud’s theory of psychosexual development by adding social and cultural aspects and proposing a lifespan development model. His theory of psychosocial development outlined eight stages, each marked by a specific crisis to resolve, that shape an individual’s identity and relationships.

Critical Evaluation

Does evidence support Freudian psychology? Freud’s theory is good at explaining but not predicting behavior (which is one of the goals of science ).

For this reason, Freud’s theory is unfalsifiable – it can neither be proved true or refuted. For example, the unconscious mind is difficult to test and measure objectively. Overall, Freud’s theory is highly unscientific.

Despite the skepticism of the unconscious mind, cognitive psychology has identified unconscious processes, such as procedural memory (Tulving, 1972), automatic processing (Bargh & Chartrand, 1999; Stroop, 1935), and social psychology has shown the importance of implicit processing (Greenwald & Banaji, 1995). Such empirical findings have demonstrated the role of unconscious processes in human behavior.

However, most evidence for Freud’s theories is from an unrepresentative sample. He mostly studied himself, his patients, and only one child (e.g., Little Hans ).

The main problem here is that the case studies are based on studying one person in detail, and regarding Freud, the individuals in question are most often middle-aged women from Vienna (i.e., his patients).

This makes generalizations to the wider population (e.g., the whole world) difficult. However, Freud thought this unimportant, believing in only a qualitative difference between people.

Freud may also have shown research bias in his interpretations – he may have only paid attention to information that supported his theories, and ignored information and other explanations that did not fit them.

However, Fisher & Greenberg (1996) argue that Freud’s theory should be evaluated in terms of specific hypotheses rather than a whole. They concluded that there is evidence to support Freud’s concepts of oral and anal personalities and some aspects of his ideas on depression and paranoia.

They found little evidence of the Oedipal conflict and no support for Freud’s views on women’s sexuality and how their development differs from men’.

Bargh, J. A., & Chartrand, T. L. (1999). The unbearable automaticity of being. American psychologist, 54 (7), 462.

Breuer, J., & Freud, S. (1895). Studies on hysteria . Standard Edition 2: London.

Fisher, S., & Greenberg, R. P. (1996). Freud scientifically reappraised: Testing the theories and therapy . John Wiley & Sons.

Freud, S. (1894). The neuro-psychoses of defence . SE, 3: 41-61.

Freud, S. (1896). Further remarks on the neuro-psychoses of defence . SE, 3: 157-185.

Freud, S. (1900). The interpretation of dreams . S.E., 4-5.

Freud, S. (1901). The psychopathology of everyday life. SE, 6. London: Hogarth .

Freud, S. (1905). Three essays on the theory of sexuality. Se , 7 , 125-243.

Freud, S. (1915). The unconscious . SE, 14: 159-204.

Freud, S. (1920) . Beyond the pleasure principle . SE, 18: 1-64.

Freud, S. (1923). The ego and the id . SE, 19: 1-66.

Freud, S. (1925). Negation. Standard edition , 19, 235-239.

Freud, S. (1961). The resistances to psycho-analysis. In T he Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume XIX (1923-1925): The Ego and the Id and other works (pp. 211-224).

Greenwald, A. G., & Banaji, M. R. (1995). Implicit social cognition: attitudes, self-esteem, and stereotypes. Psychological review, 102 (1), 4.

Stroop, J. R. (1935). Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. Journal of experimental psychology, 18 (6), 643.

Tulving, E. (1972). Episodic and semantic memory. In E. Tulving & W. Donaldson (Eds.), Organization of Memory , (pp. 381–403). New York: Academic Press.

What is Freud most famous for?

Why is freud so criticized, what did sigmund freud do.

His conceptualization of the mind’s structure (id, ego, superego), his theories of psychosexual development, and his exploration of defense mechanisms revolutionized our understanding of human psychology.

Despite controversies and criticisms, Freud’s theories have fundamentally shaped the field of psychology and the way we perceive the human mind.

What is the Freudian revolution’s impact on society?

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Agriculture

- Armed forces and intelligence services

- Art and architecture

- Business and finance

- Education and scholarship

- Individuals

- Law and crime

- Manufacture and trade

- Media and performing arts

- Medicine and health

- Religion and belief

- Royalty, rulers, and aristocracy

- Science and technology

- Social welfare and reform

- Sports, games, and pastimes

- Travel and exploration

- Writing and publishing

- Christianity

- Download chapter (pdf)

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Freud, sigmund.

- Susan Austin

- https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/55514

- Published in print: 23 September 2004

- Published online: 23 September 2004

- This version: 06 January 2011

- Previous version

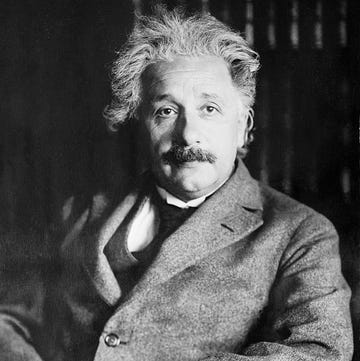

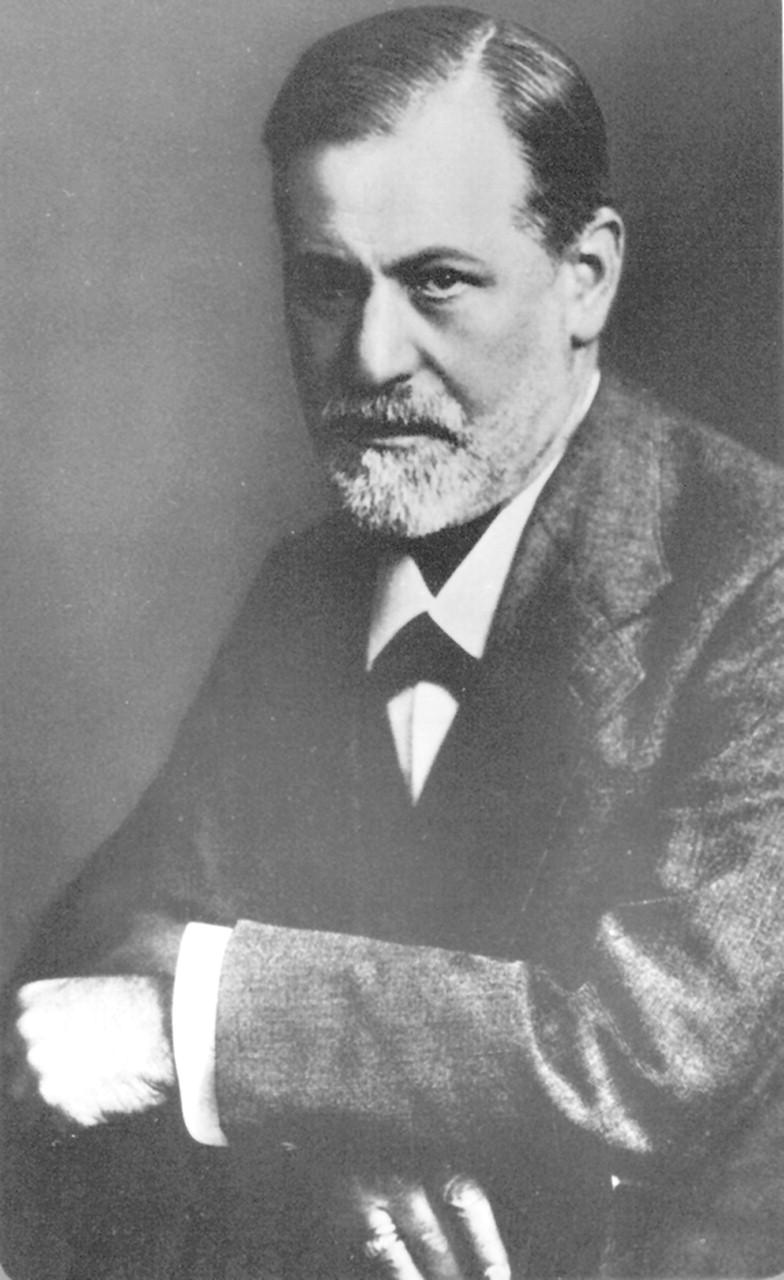

Sigmund Freud ( 1856–1939 )

by Max Halberstadt , 1921

Freud, Sigmund ( 1856–1939 ), founder of psychoanalysis , was born on 6 May 1856 at Freiberg, Moravia, in the Austro-Hungarian empire (later Príbor, Czech republic), the first of the seven surviving children of Jacob Freud (1815–1896) , wool trader, and his second wife, Amalie (1835–1931) , daughter of Jacob Nathansohn and his wife, Sara . His parents were both Jewish and Freud himself went to London as a refugee in 1938.

Childhood and adolescence

The Freud family occupied one large room on the first floor of a house owned by a blacksmith. His father, at one point registered as a wool merchant, made what must have been a somewhat precarious living through trade of various kinds. His mother was an attractive and strong-minded woman and by all accounts her love for Sigmund , the first-born of her eight children, was boundless. There followed two more boys, one of whom died at six months, and five girls, whose arrival stirred up intense jealousy in Freud . Freud's position in the family was unusual in that he also had two grown-up half-brothers from his father's first marriage, one of whom had a young son, so that Freud was born an uncle. This nephew, John , was Freud's closest child companion and rival. Freud remarked, in The Interpretation of Dreams , that his characteristic warm friendships as well as his enmities with contemporaries went back to this early relationship ( Freud , Interpretation , 483 ). The two half-brothers and the young boy emigrated to Manchester at the end of Freud's third year, stimulating in him early thoughts of moving to England himself, which he was eventually to do some eighty years later.

Meanwhile, in 1860, when Freud was four, in common with many other Jews of the Austro-Hungarian empire at that time the family moved to Vienna in the wake of a recent liberalization of policy which gave Jews equal political rights and abolished ghettos. Although the family were largely non-observing Jews, ready to assimilate into Viennese society, and all his life Freud was himself an atheist, Jewishness in its religious, cultural, and political aspects was a lifelong preoccupation of his and very much a part of his identity.

The family settled in Leopoldstadt, a mainly Jewish part of the city, where they lived in straitened conditions. Little is known of these first years in Vienna and Freud's early schooling. Although it is unclear quite how Jacob Freud earned a living once there, the family seems to have been able to make ends meet. Freud's education at the excellent local Gymnasium , which he entered in 1865, proceeded without interruption and he received a classical education. He was consistently head of the class. He and his schoolfriend Eduard Silberstein , who remained a lifelong friend, formed their own ‘Spanish Academy’ with an exclusive membership of two, which involved corresponding in self-taught Spanish through which they divulged to each other their thoughts, fantasies, and preoccupations and developed a sort of private mythology. Their correspondence continued from Freud's mid-teens to his mid-twenties, stopping about the time that he met his future wife.

Freud's early biography is of fundamental significance to the history of psychoanalysis, as, through his own rigorous self-analysis—which he was to conduct from the mid-1890s—he effectively made himself the subject of the first psychoanalytic case-history. Freud makes thinly disguised references to his personal experience throughout his psychoanalytical writings, most notably in Die Traumdeutung (1900), published in English as The Interpretation of Dreams . A less intimately personal account is his Selbstdarstellung ( 'Autobiographical study' , 1925), which was commissioned as part of a series of self-portraits by men of science, and focuses on his professional development. In a postscript of 1935 he writes: ' The story of my life and the history of psychoanalysis … are intimately interwoven … no personal experiences of mine are of any interest in comparison to my relations with that science ' ( p. 71 ). In fact Freud's most personal experience was inevitably bound up with psychoanalysis, while it is true that outwardly his private life, typical of a bourgeois doctor, appears unremarkable.

Studies in medicine, neurology, and psychiatry

In spite of the family's financial situation Freud was left by his father to make his own choice of career. He began his medical studies at Vienna University in 1873, availing himself of the considerable degree of academic freedom afforded by the curriculum to explore a variety of areas. His interest gravitated towards scientific research at the outset. He chose to supplement his studies with research in the laboratories of faculty members, undertaking such research for Ernst Brücke , a congenial teacher of physiology and histology, and he remained at Brücke's laboratory for six years. Beginning with studies of nerve cell structure in the Petromyzon , a primitive species of fish, and progressing to human anatomy and a minute study of the medulla oblongata, he established a solid reputation as a specialist in brain anatomy and pathology. In addition to Brücke himself, who was for Freud something of a father figure, Brücke's laboratory brought the young Freud into contact with distinguished colleagues. It was at Brücke's that Freud made the acquaintance of Dr Josef Breuer , another father figure whose personal support and professional collaboration he later acknowledged as crucial to the foundation of psychoanalysis.

It was during this period that Freud made his first long-awaited journey to England in 1875 to visit his half-brothers in Manchester, and which he acknowledged, seven years later, in a letter to his fiancée, as a decisive influence. He had dreamed of England since boyhood and had acquired an insatiable appetite for English literature, especially Shakespeare and Dickens . The trip stimulated renewed yearnings to settle there himself. Jacob Freud had hoped this stay with cousins more successful in business than himself would stimulate in Freud some enthusiasm in that line, but Freud was nurturing fantasies of pursuing a scientific career in England, for all its ' fog and rain, drunkenness and conservatism ' ( Letters to … Silberstein , 127 ). As a result of the excursion and his encounter with the consistent empiricism in the English scientific writings of the likes of John Tyndall , Thomas Huxley , Charles Lyell , and Charles Darwin , his own interests became more sharply focused. Correspondingly he declared himself increasingly wary of metaphysics and philosophy ( ibid., 128 ).

Freud's studies were interrupted by military service in 1879–80, during which he translated four essays by John Stuart Mill for the German edition of the collected works. After receiving his medical qualification in 1881 he pursued his research at Brücke's laboratory, having been given a temporary post. In 1882 Freud suddenly left Brücke's laboratory and began to set himself up to pursue a clinical career, which afforded the eventual prospect of financial security by going into private practice. Significantly, the change of direction coincided with Freud's falling in love with Martha Bernays ( b . 1861) , his future wife, the daughter of an observing Jewish family well known in Hamburg. There followed a four-year engagement, during which he wrote his fiancée 900 letters while struggling to establish himself financially in keeping with conventional expectation.

In the meantime Freud somewhat belatedly began a three-year residency at the Viennese General Hospital, an internationally renowned teaching centre where the heads of department were almost invariably pre-eminent in their fields. Although Freud's career was full of promise during this period, the prospect of becoming materially secure remained remote and he was searching for new discoveries so as to make his name. One such project was concerned with the applications of cocaine, then new and relatively unknown. In 1884 Freud published an enthusiastic paper based on his experiments on himself and others. Unfortunately it was left to a contemporary, Koller , whose attention Freud had drawn to cocaine's anaesthetic qualities, to complete an investigation into such use in eye surgery and so to claim the considerable credit for the discovery.

In July 1885, a month after being appointed to the academic post of privat-docent , Freud left for Paris on a travelling scholarship to study at the Salpêtrière Hospital under the celebrated neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot . In contrast to the Viennese psychiatric approach Freud had so far encountered, which was concerned with physical symptoms and family pathology with little attempt to identify causes, Charcot was developing bold concepts for understanding neurosis through observing patients, in particular hysterics, with a view to characterizing disorders and establishing their aetiology. The trip to Paris was of fundamental significance to Freud's intellectual and professional development. Having arrived there primarily preoccupied with his anatomical researches, by the time of his return to Vienna his interest had turned, through Charcot's influence, to psychopathology and the applications of hypnosis.

In the wake of his formative experience in Paris, Freud gave addresses to the Vienna Medical Society championing Charcot's views on hysteria and hypnosis. These presentations met with cool receptions, to Freud's great disappointment. There was widespread scepticism concerning hypnosis and it is quite possible that Freud's youthful idealization of his French master may have rankled with his senior colleagues, reinforcing Freud's consistently held view of himself as an outsider embattled with the medical establishment.

Marriage and early career

Soon after his return from Paris, Freud set himself up in private practice as a consultant in nervous diseases, of which hysteria was one of the most important. Referrals came in particular from his older friend and benefactor Breuer , with whom he was later to collaborate. After years of relative poverty, Freud had generated enough income to marry Martha Bernays on 13 September 1886 at Wandsbeck, just outside Hamburg. The couple settled down to a domestic regime typical of a Viennese doctor's family and Martha had six children, three boys and three girls, within eight years. The household also included Martha's unmarried sister, Minna , who was able to provide Freud with intellectual companionship through the initial years of relative isolation.

During the first years of married life in addition to his private practice Freud was director of neurology at the Institute for Children's Diseases, where he continued his work on brain neurology in addition to clinical duties with neurological patients, enabling him to support his young family while he pursued his greater interest in clinical psychopathology through his private practice of neurotic patients. Of the neurological papers he published as a result of the neurological post one in particular foreshadows his later work. 'Zur Auffassung der Aphasien: eine kritische Studie' ( 'On aphasia' , 1891) reviewed the existing literature, criticizing its mechanical approach and reliance on brain mythology, which attributed mental functioning to particular parts of the brain, proposing instead a subtle relationship between anatomy and psychology.

The ' talking cure '

Freud's treatment of patients by hypnosis continued for a decade after his visit to Paris, although he became increasingly aware of its limitations. A fundamental shift in his thinking evolved following his re-encounter with a case history which his older friend Breuer had related to him as early as 1882. Breuer had been treating an intelligent and lively minded young woman, known as Anna O. , whose severely debilitating symptoms included paralysis, loss of speech, and a nervous cough. Taking his lead from the patient Breuer developed a cathartic method, which the patient herself called a ' talking cure '. Freud managed to persuade Breuer to revive the method, by which the doctor–patient relationship had effectively been transformed from one of passivity on the part of the hypnotized patient receiving suggestions from the doctor aimed at ridding the patient of the symptom, to that of a patient actively talking in a self-induced trance to a doctor who received information while the patient simultaneously relieved herself of the symptom, which emerged as the product of some early trauma which had not been resolved.

Implicit in the cathartic method which Freud adopted to treat his own patients were several concepts which were to be at the heart of psychoanalytic thinking: namely, that patients were suffering from ' reminiscences '—there was a causal link between hysterical symptoms and psychological trauma; that the traumatic experience had been rendered unconscious through repression, yet continued to make its presence felt; and that the unconscious experience could be made conscious, bringing relief to the patient.

An account of the case of Anna O. was eventually published by Freud and Breuer in Studien über Hysterie ( 'Studies on hysteria' , 1895). Breuer had been consistently reticent about the Anna O. case, which contained elements which he found personally embarrassing, and it was left to the intrepid younger man to explore the implications of the new method which had presented itself as a viable alternative to hypnosis. It was not until 1896 that Freud used the term ‘psychoanalysis’.

Freud widened the scope of the treatment by taking an interest in anything a patient might have to say, rather than inviting an account of the symptoms. Freud named this process free association and its encouragement was the object of the enduring fundamental rule of psychoanalysis, whereby a patient is asked to say whatever comes to mind. With the advent of free association came the demise of the last vestige of the hypnotic method, as Freud now refrained from applying gentle pressure to the patient's head during treatment. The setting for psychoanalysis later recommended by Freud , where the patient reclines comfortably while the analyst sits out of sight, was designed to facilitate free association. The request to patients to associate freely threw into relief resistance, a term which Freud used interchangeably with defence at that time. Listening to patients' accounts Freud became convinced that the traumas which lay behind hysterical symptoms had their origins in infancy and he was struck by their sexual content.

Family, friends, and colleagues

Freud's last daughter, Anna Freud , was born in 1895, the year of the publication with Breuer of Studien über Hysterie . His father died in the following year. Although he found pleasure in fatherhood and in the family home created by Martha Freud , there was no real intellectual outlet for Freud as he struggled to develop a theoretical framework for psychoanalysis and subjected himself to the emotional strain of a lengthy self-analysis. Freud's friendship with Breuer had been faltering since the late 1880s and eventually broke down, largely because Breuer was unwilling to concur with Freud's firm conviction about the sexual aetiology of hysteria. It was Wilhelm Fliess , a talented but ultimately discredited Berlin general practitioner, who fulfilled Freud's need for a friend, confidant, and critic. Fliess was closer in age to Freud and unlike Breuer could not be shocked by Freud's more audacious speculations. The relationship quickly developed a great intensity and the two kept up an intimate correspondence for fifteen years from 1887 to 1902 which sheds light on the otherwise obscure evolution of Freud's thinking at that time and on his concurrent self-analysis. It was in a long letter to Fliess written in 1895 that Freud set out his portentous 'Project for a scientific psychology' with a view to integrating mental and physical phenomena within a single theoretical schema. Freud began work on the 'Project' in the late summer of 1895 in a rush of creativity following one of his ' congresses ' with Fliess . His ambition was to set out a psychology firmly grounded in neurology and biology, which he referred to as his 'Psychology for neurologists' . Freud likened the task to an exhausting but exhilarating mountain climb, during which more peaks to be conquered kept appearing. Exhilaration soon gave way to frustration and dejection however, and by November he wrote to Fliess that he could ' no longer understand the mental state in which I hatched the Psychology ' ( Freud , Project for a scientific psychology, 1895, 152 ). The undeniably abstruse draft survives only among Fliess's papers, and Freud makes no mention of this momentous effort in his autobiographical accounts. It was published posthumously in English in 1954, four years after publication in German, having been rescued from Fliess's papers by Marie Bonaparte following his death in 1931, and edited by James Strachey ( Standard Edition , vol. 1 ). As Strachey points out in his editor's introduction Freud clearly regarded this ostensibly neurological work as a failure. Although it cannot be said to constitute the foundation of psychoanalytic theory as such, it contained the seeds of many ideas elaborated in his later psychological writings, for example drive theory, repression, and an economy of mind based on mental conflict.

Freud's friendship with Fliess was destined to collapse amid recriminations, with Fliess alleging that Freud had appropriated his ideas on inherent bisexuality without acknowledgement. Ten years later Freud's friendship with Jung was also to end acrimoniously, with Jung's questioning of the sexual origins of neurosis at the centre of the dispute. Long before the split with Jung , and in the period preceding his violent quarrel with Fliess in 1900, Freud reflected on the nature of his relationships to contemporaries, which he linked to his intensely ambivalent attachment to his nephew John , who had moved to England when Freud was three.

My emotional life has always insisted that I should have an intimate friend and a hated enemy. I have always been able to provide myself afresh with both, and it has not infrequently happened that the ideal situation of childhood has been so completely reproduced that friend and enemy have come together in a single individual—though not, of course, both at once or with constant oscillations, as may have been the case in my early childhood. Freud, Interpretation , 483

Fortunately for Freud this easily discernible pattern of turbulent relationships prone to eventual breakdown was restricted to close male colleagues. His family relationships and other friendships were contrastingly consistent and loyal. It was no coincidence that the professional disagreements which caused these intimate friendships to break down were concerned with Freud's insistence on the centrality of sexuality. Sexuality represented to Freud the direct and essential instinctual link between psychology and biology, without which he would find himself caught up in the dichotomy of mind and body which he was desperate to avoid.

Establishment of psychoanalysis

Later in his career Freud recalled the 1890s as years in an intellectual wilderness. His papers on hysteria had not won the respect of the medical establishment and he was aware of his Jewishness in that largely Catholic milieu. In addition Freud had confessed his own surprise that ' the case histories I write should read like short stories and that, as one might say, they lack the serious stamp of science ' ( Standard Edition , 2.160 ).

Until the late 1890s Freud's observations of the infantile and sexual origins of hysteria had led him to believe, through listening to his patients' accounts, that his patients had fallen ill as a result of childhood sexual abuse by adults. In 1897 he modified this theory of actual childhood seduction and proposed instead that these accounts were often derived from infantile sexual fantasies and therefore belonged in the realm of the patient's own psychic reality and were not, as he had previously thought, necessarily objective facts. To Freud children were no longer assumed to be innocents in a world of adult sexuality: they possessed sexual feelings and wishes of their own which were liable to repression, elaboration, and distortion during development. This shift in Freud's thinking has proved enduringly controversial. Critics have argued that patients' experiences have been denied through their reassignment by Freud to subjective reality and that he changed tack in this way only because he shied away from alienating bourgeois Vienna by reporting widespread sexual abuse in its families. In fact, Freud never denied the reality of child sexual abuse, and it was his attribution of sexual feelings to children which most shocked his contemporaries. Freud was not to be deterred from his line of enquiry. Indeed the cynicism of his medical contemporaries and outrage from members of the wider public seem to have acted as a spur to new vistas opening up. In addition to setting the scene for the detailed exposition of human development, for example in the later Drei Abhandlungen zur Sexualtheorie ( 'Three essays on the theory of sexuality' , 1905), the recasting of the aetiology of hysteria in the light of childhood sexuality paved the way to a more general understanding of the role of impulse and desire in the human mind, rendered unconscious through repression.

With the publication of Die Traumdeutung in 1900 Freud decisively challenged the accepted limits of scientific psychology, by bringing mental phenomena generally considered beyond the pale, such as dreams, imagination, and fantasy, into the fold. The leitmotif which runs throughout the book is that dreams represent the disguised fulfilment of repressed infantile wishes and that as such ' the interpretation of dreams is the royal road to a knowledge of the unconscious activities of the mind ' ( Freud , Interpretation , 608 ).

Freud stated at the outset that his theory of dreams was generally applicable and not restricted to neurotic patients. Indeed, his curiosity about the nature of dreams had been aroused during his self-analysis and the bulk of the illustrative material was trawled from his own dreams and autobiographical material, along with dreams of friends and children. It was in The Interpretation of Dreams that Freud , drawing characteristically on his classical schooling, introduced the Oedipus complex, which asserts the universal desire of a child for the parent of the opposite sex and consequent hatred of the parent of the same sex, which must be resolved through repression in order for normal development to proceed. Although sales were slow and a second edition was not needed until 1909, Freud's explorations of normal psychological functioning did stimulate interest in a wider public.

At the time of writing his dream book Freud was planning other studies of normal psychological processes which would none the less plumb the depths of the psyche, namely Zur Psychopathologie des Alltagslebens ( 'The psychopathology of everyday life' , 1901), which explored the unconscious meaning of everyday slips of the tongue and bungled actions, and Der Witz und seine Beziehung zum Unbewussten ( 'Jokes and their relation to the unconscious' , 1905) for which he drew on his repertoire of ' profound Jewish stories '.

The early years of the century also saw the publication of the first of five substantial case histories which read rather like novellas, the case of Dora , under the title Fragment of an Analysis of a Case of Hysteria (1905 [1901]). The most important insight from the analysis of Dora , which broke down when the young woman left, came to Freud with hindsight. In a postscript, Freud reviews the analysis in the light of transference. The phenomenon of transference, whereby any individual's experience of early relationships is the blueprint for later relationships, had already been discussed in the Studies on Hysteria (1895) in terms of an unconscious false connection on the part of the patient between the physician and some earlier figure. Now, reflecting on Dora's inability to continue with her analysis, Freud became aware of the implications of the understanding of transference as a key factor in the therapeutic process of psychoanalysis: ' Transference, which seems ordained to be the greatest obstacle to psychoanalysis, becomes its most powerful ally, if its presence can be detected each time and explained to the patient ' ( Standard Edition , 7.117 ).

During this period Freud's home life remained settled. As his financial situation improved he was able to indulge his two great interests: Mediterranean travel and collecting antiquities, another natural consequence of a youth steeped in the classics. He also found time to follow the exciting archaeological discoveries being made at the time, and often cited archaeological excavation as a metaphor for psychoanalytic work, with its interest in painstakingly uncovering hidden layers and origins. In 1907 Freud made the first trip to England since his inspirational visit aged nineteen. He spent a fortnight visiting Manchester relatives who showed him Blackpool and Southport before he departed for London. He returned full of praise for the architecture and people, having seen the Egyptian antiquities at the British Museum. It was not until the hasty move to London in 1938 that Freud once again found himself in his childhood dreamland.

Freud's interests beyond the consulting room and the application of psychoanalytic theory to new areas became increasingly apparent in his writings in the years preceding the First World War. Greek literature had already yielded the Oedipus story and there followed other forays into literature and art history, with Der Wahn und die Träume in W. Jensen's ‘Gradiva’ ( 'Delusions and dreams in Jensen's “Gradiva”' , 1907) and Eine Kindheitserinnerung des Leonardo da Vinci ( 'Leonardo da Vinci and a memory of his childhood' , 1910). In Totem und Tabu ( 'Totem and taboo' , 1913), Freud applied psychoanalysis to anthropological material for the first time.

The psychoanalytic movement

As a privat-docent and from 1902 a professor extraordinarius Freud was entitled to lecture at Vienna University. These lectures attracted a small group of followers composed of both laymen and doctors. From 1902 onwards they met as the Wednesday Psychological Society , which evolved into the Vienna Psychoanalytical Society in 1908. In the meantime, to his great satisfaction, Freud's reputation began to spread beyond Vienna and he began to attract interest from foreigners, among them the well-known psychiatrist Eugen Bleuler and his young assistant Carl Jung . Others included Karl Abraham and Max Eitington , also from the Burghölzli Clinic in Switzerland, who unlike Jung were to remain loyal disciples, the Hungarian Sándor Ferenczi , and the Welshman (Alfred) Ernest Jones , Freud's future biographer and the founder of the British Psycho-Analytical Society .

The year after the Vienna Psychoanalytical Society was founded Freud made his only trip to the United States to give a series of well-received lectures ( Five Lectures on Psycho-Analysis , in Standard Edition , vol. 11 ) at the invitation of Clark University, Massachusetts, accompanied by Jung , Ferenczi , and Jones . The spread of psychoanalysis gained momentum and new societies were formed on the model of the Viennese. An international association was established in 1908, uniting the various groups and promising a structure which Freud hoped would facilitate the perpetuation of psychoanalysis through training. Inevitably psychoanalytic politics were in the air and Freud found himself at the centre of rivalries, jealousies, and dissenting views between individuals and groupings, notably his original Viennese colleagues and the Zürich analysts, whom he was felt to favour. Disagreements led to defection by some members, most significantly by Alfred Adler and Jung , whom Freud had thought of as his successor. In an attempt to protect the essence of psychoanalysis from distortion a ‘secret committee’ was formed, at the suggestion of Ernest Jones , which was intended to provide a secure setting within which theory and technique could be discussed among an inner circle of loyal colleagues which consisted of Ernest Jones , Sándor Ferenczi , Karl Abraham , Hanns Sachs , Otto Rank , and, later, Max Eitington . Although the committee met into the 1920s, its conspiratorial air set an unfortunate tone for the future functioning and reputation of the profession.

Further developments

Inevitably the First World War interrupted Freud's well-established working routine. His three sons, Martin , Ernst (father of the writer and broadcaster Clement Freud and the painter Lucian Freud ), and Oliver were all in active service and the real possibility of losses within the family had to be faced. Patients stopped coming, and the international psychoanalytical movement's activities came to a halt. Freud was left more time for private study, which proved very productive. There were papers which resulted from reflections on the war itself, for example 'Zeitgemässes über Krieg und Tod' ( 'Thought for the times on war and death' ). The Vienna University lectures delivered during the war were published as the Vorlesungen zur Einführung in die Psychoanalyse ( 'Introductory lectures on psychoanalysis' , 1916–17); of particular significance were his Papers on Metapsychology ( Standard Edition , vol. 14), of which only five of an original twelve have survived. Dealing with five fundamental themes of psychoanalysis they are 'On narcissism' , 'Instincts and their vicissitudes' , 'Repression' (all 1915), 'The unconscious' , and 'Mourning and melancholia' (both 1917). Freud went far beyond summing up his theories as they stood in these highly technical papers. In addition to containing new ideas they also hint at numerous revisions which would preoccupy him during the last phase of his career.

By the end of the First World War, Vienna—no longer at the centre of an empire—had become merely the capital of a small, impoverished country. After resuming his private practice Freud took on several British and American patients who proved a useful source of hard currency as a safeguard against soaring inflation. The most serious British interest in Freud came from the members of the Bloomsbury group , in keeping with their characteristic receptiveness to progressive European ideas. Frances Partridge , who lodged with the Stracheys in Gordon Square during their early years as practising analysts, recalled how psychoanalysis was very much part of the Bloomsbury scene, and that she would often recognize patients as they arrived at the house for their sessions. Among the British were the Bloomsbury couple, James Strachey and Alix Strachey [ see under Strachey, James ]. Introductions, through Ernest Jones , were eased by the fact that Freud admired the work of James's older brother, Lytton Strachey . Freud took James Strachey into analysis on condition that he begin translating his writings into English. Translating Freud , culminating with the publication of the complete works in twenty-four volumes by Virginia and Leonard Woolf's Hogarth Press , was to occupy Strachey for the rest of his life, and remains the standard text for the extensive scholarship on Freud in English, and for psychoanalysts without German. The Strachey translation has been criticized for its recourse to dry scientific neologisms where Freud made use of plain German. For example, Strachey's term ' cathexis ', now well established as a psychoanalytic term, takes the place of Freud's ' Besetzung ', a common German word with rich nuances of meaning.

The first international congress following the war was held at The Hague in 1920, which Freud attended in the company of his youngest daughter, Anna , the only one of his children to take an active interest in psychoanalysis, who was now training as an analyst herself and in analysis with her own father. Freud's three sons had survived the war, and the two elder girls, Mathilde and Sophie , were by now married. Disaster struck, though, in 1920, when Sophie , Freud's ' Sunday Child ', died suddenly leaving a husband and two small boys. Three years later one of Sophie's children died of tuberculosis in the family's care in Vienna, aged four. Freud took the loss very hard—perhaps, as he reflected in a letter to his writer friend Romain Rolland , because it came soon after the shock of discovering that he was suffering from cancer of the jaw, from which he died some sixteen years later. The cancer, brought about by years of heavy cigar smoking, necessitated thirty-three operations and constant nursing attention from his daughter Anna in an attempt to contain it, and the fitting of an awkward oral prosthesis. Freud was not deterred from smoking cigars, however, and indeed remained convinced of their therapeutic qualities: ' I believe I owe to the cigar a great intensification of my capacity to work and a facilitation of my self control ' ( Ward , 14 ). The great majority of photographs of Freud show him holding a cigar. Always the perfect bourgeois, impeccably groomed throughout his life, his once well-filled features lost their softness in later years, probably as much from the illness as ageing. This has no doubt contributed to the popular image of Freud as a stern and distant figure. Less formal photographs and home movies taken on family occasions and holidays, however, convey a more relaxed and accessible family man, although his smile was rarely captured on camera.

During the 1920s Freud expanded his metapsychological theories. Two key strands can be identified in his thinking from this period onwards: a systematic study of the ego and a preoccupation with cultural and social issues in response to the crisis of humanity during the recent war. At its more speculative, psychoanalytic theory now resembled the philosophical enquiry Freud had eschewed early in his career in favour of scientific methods.

In Jenseits des Lustprinzips ( 'Beyond the pleasure principle' , 1920), Freud revised his theory of the instincts by positing a death instinct. Psychic conflict could now be construed in terms of the opposing forces of love and death, as could human behaviour and interaction at large. Broadly speaking the emphasis in his thinking had shifted from the unconscious itself to the phenomenon of resistance, which he understood to exert constant pressure to keep unacceptable desires from surfacing. Freud's interest turned to the ego, the agent of this defensive activity, and to the classification of the defences at the ego's disposal. It no longer made sense to think purely in terms of conscious and unconscious, because in any case the mechanisms of defence employed by the ego were themselves unconscious. This new phase of work on the ego was initiated in Massenpsychologie und Ich-analyse ( 'Group psychology and the analysis of the ego' , 1921). Freud then set out an extensively revised tripartite model of the structure and functions of the mind, in Das Ich und das Es ( 'The ego and the id' , 1923). The third agency, which he termed the super-ego, was conceived to take into account the crucial internalization of parental authority and prohibition which came about with the dissolution of the Oedipus complex.

Once again new avenues had opened up to Freud as the result of an innovation, for example the possibility of classifying mental illness in terms of its origins in a conflict between parts of the personality. In a brief paper entitled 'Neurosis and psychosis' (1923), Freud offered new clarity with the following formulation: ' Transference neuroses correspond to a conflict between the ego and the id; narcissistic neuroses, to a conflict between the ego and the superego; and psychoses, to a conflict between the ego and the external world ' ( Standard Edition , 19.152 ). Other rewards reaped by Freud from the new structural theory were the linking of particular defences to specific mental illnesses and new insights into the nature of anxiety ( Hemmung, Symptom und Angst ( 'Inhibitions, symptoms and anxiety' ), 1926).

Freud continued working in great pain after an initial operation for the cancer in 1923. The international psychoanalytic movement had re-established itself, with important centres elsewhere, for example in Berlin, which was presided over by Freud's disciple, Abraham . Ernest Jones had founded the London Psycho-Analytical Society in 1913, which became the British Psycho-Analytical Society in 1919. The London Institute of Psycho-Analysis was formally founded by Jones in late 1924. An international structure for training was now in place, with a training analysis as its cornerstone, conducted by Freud and a growing number of senior analysts. Among the patients to consult Freud in the mid-1920s was Princess Marie Bonaparte , wife of Prince George of Greece , a woman endowed with a lively intelligence, tremendous energy, and great material wealth. She soon began training as an analyst and went on to become a leading figure in the international movement, a patron of psychoanalysis, and a close friend of the Freud family, who secured their safe passage from Vienna in 1938.

Another woman important to Freud was his youngest child, Anna , who was by now making her name as an analyst and who increasingly acted internationally as her father's ambassador as his illness rendered him more immobile. She represented her father at the 1929 International Congress in Oxford, in difficult circumstances following a dispute with the New York analysts about whether non-medical individuals should be allowed to become analysts. Freud was exasperated, and his deep-seated antagonism to all things American was fuelled. Freud stood firm: he had already tackled this problem in 1926 in response to allegations of quackery made to a lay colleague, arguing that psychoanalysis was more than a mere offshoot of medicine and that its practice should therefore not be restricted in this way ( Die Frage der Laienanalyse ; 'The question of lay analysis' , 1926; in Freud , Standard Edition , vol. 20).

From the publication of Die Zukunft einer Illusion ( 'The future of an illusion' , 1927), which dissected religious belief, Freud's other great bête noire , the majority of Freud's writing dealt with cultural and wider social issues. In 1930 came Das Unbehagen in der Kultur ( 'Civilisation and its discontents' ), in which he subjected civilization itself to scrutiny, asking, in the light of his experience with neurotics in clinical practice, whether instincts were unduly repressed by society. For Freud these works represented a return to his intellectual beginnings: ' My interest, after making a lifelong détour through the natural sciences, medicine and psychotherapy, returned to cultural problems which had fascinated me long before when I was a youth scarcely old enough for thinking ' ( Standard Edition , 20.72 ).