The Will to Teach

Critical Thinking in the Classroom: A Guide for Teachers

In the ever-evolving landscape of education, teaching students the skill of critical thinking has become a priority. This powerful tool empowers students to evaluate information, make reasoned judgments, and approach problems from a fresh perspective. In this article, we’ll explore the significance of critical thinking and provide effective strategies to nurture this skill in your students.

Why is Fostering Critical Thinking Important?

Strategies to cultivate critical thinking, real-world example, concluding thoughts.

Critical thinking is a key skill that goes far beyond the four walls of a classroom. It equips students to better understand and interact with the world around them. Here are some reasons why fostering critical thinking is important:

- Making Informed Decisions: Critical thinking enables students to evaluate the pros and cons of a situation, helping them make informed and rational decisions.

- Developing Analytical Skills: Critical thinking involves analyzing information from different angles, which enhances analytical skills.

- Promoting Independence: Critical thinking fosters independence by encouraging students to form their own opinions based on their analysis, rather than relying on others.

Creating an environment that encourages critical thinking can be accomplished in various ways. Here are some effective strategies:

- Socratic Questioning: This method involves asking thought-provoking questions that encourage students to think deeply about a topic. For example, instead of asking, “What is the capital of France?” you might ask, “Why do you think Paris became the capital of France?”

- Debates and Discussions: Debates and open-ended discussions allow students to explore different viewpoints and challenge their own beliefs. For example, a debate on a current event can engage students in critical analysis of the situation.

- Teaching Metacognition: Teaching students to think about their own thinking can enhance their critical thinking skills. This can be achieved through activities such as reflective writing or journaling.

- Problem-Solving Activities: As with developing problem-solving skills , activities that require students to find solutions to complex problems can also foster critical thinking.

As a school leader, I’ve seen the transformative power of critical thinking. During a school competition, I observed a team of students tasked with proposing a solution to reduce our school’s environmental impact. Instead of jumping to obvious solutions, they critically evaluated multiple options, considering the feasibility, cost, and potential impact of each. They ultimately proposed a comprehensive plan that involved water conservation, waste reduction, and energy efficiency measures. This demonstrated their ability to critically analyze a problem and develop an effective solution.

Critical thinking is an essential skill for students in the 21st century. It equips them to understand and navigate the world in a thoughtful and informed manner. As a teacher, incorporating strategies to foster critical thinking in your classroom can make a lasting impact on your students’ educational journey and life beyond school.

1. What is critical thinking? Critical thinking is the ability to analyze information objectively and make a reasoned judgment.

2. Why is critical thinking important for students? Critical thinking helps students make informed decisions, develop analytical skills, and promotes independence.

3. What are some strategies to cultivate critical thinking in students? Strategies can include Socratic questioning, debates and discussions, teaching metacognition, and problem-solving activities.

4. How can I assess my students’ critical thinking skills? You can assess critical thinking skills through essays, presentations, discussions, and problem-solving tasks that require thoughtful analysis.

5. Can critical thinking be taught? Yes, critical thinking can be taught and nurtured through specific teaching strategies and a supportive learning environment.

Related Posts

7 simple strategies for strong student-teacher relationships.

Getting to know your students on a personal level is the first step towards building strong relationships. Show genuine interest in their lives outside the classroom.

Connecting Learning to Real-World Contexts: Strategies for Teachers

When students see the relevance of their classroom lessons to their everyday lives, they are more likely to be motivated, engaged, and retain information.

Encouraging Active Involvement in Learning: Strategies for Teachers

Active learning benefits students by improving retention of information, enhancing critical thinking skills, and encouraging a deeper understanding of the subject matter.

Collaborative and Cooperative Learning: A Guide for Teachers

These methods encourage students to work together, share ideas, and actively participate in their education.

Experiential Teaching: Role-Play and Simulations in Teaching

These interactive techniques allow students to immerse themselves in practical, real-world scenarios, thereby deepening their understanding and retention of key concepts.

Project-Based Learning Activities: A Guide for Teachers

Project-Based Learning is a student-centered pedagogy that involves a dynamic approach to teaching, where students explore real-world problems or challenges.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Classroom Q&A

With larry ferlazzo.

In this EdWeek blog, an experiment in knowledge-gathering, Ferlazzo will address readers’ questions on classroom management, ELL instruction, lesson planning, and other issues facing teachers. Send your questions to [email protected]. Read more from this blog.

Eight Instructional Strategies for Promoting Critical Thinking

- Share article

(This is the first post in a three-part series.)

The new question-of-the-week is:

What is critical thinking and how can we integrate it into the classroom?

This three-part series will explore what critical thinking is, if it can be specifically taught and, if so, how can teachers do so in their classrooms.

Today’s guests are Dara Laws Savage, Patrick Brown, Meg Riordan, Ph.D., and Dr. PJ Caposey. Dara, Patrick, and Meg were also guests on my 10-minute BAM! Radio Show . You can also find a list of, and links to, previous shows here.

You might also be interested in The Best Resources On Teaching & Learning Critical Thinking In The Classroom .

Current Events

Dara Laws Savage is an English teacher at the Early College High School at Delaware State University, where she serves as a teacher and instructional coach and lead mentor. Dara has been teaching for 25 years (career preparation, English, photography, yearbook, newspaper, and graphic design) and has presented nationally on project-based learning and technology integration:

There is so much going on right now and there is an overload of information for us to process. Did you ever stop to think how our students are processing current events? They see news feeds, hear news reports, and scan photos and posts, but are they truly thinking about what they are hearing and seeing?

I tell my students that my job is not to give them answers but to teach them how to think about what they read and hear. So what is critical thinking and how can we integrate it into the classroom? There are just as many definitions of critical thinking as there are people trying to define it. However, the Critical Think Consortium focuses on the tools to create a thinking-based classroom rather than a definition: “Shape the climate to support thinking, create opportunities for thinking, build capacity to think, provide guidance to inform thinking.” Using these four criteria and pairing them with current events, teachers easily create learning spaces that thrive on thinking and keep students engaged.

One successful technique I use is the FIRE Write. Students are given a quote, a paragraph, an excerpt, or a photo from the headlines. Students are asked to F ocus and respond to the selection for three minutes. Next, students are asked to I dentify a phrase or section of the photo and write for two minutes. Third, students are asked to R eframe their response around a specific word, phrase, or section within their previous selection. Finally, students E xchange their thoughts with a classmate. Within the exchange, students also talk about how the selection connects to what we are covering in class.

There was a controversial Pepsi ad in 2017 involving Kylie Jenner and a protest with a police presence. The imagery in the photo was strikingly similar to a photo that went viral with a young lady standing opposite a police line. Using that image from a current event engaged my students and gave them the opportunity to critically think about events of the time.

Here are the two photos and a student response:

F - Focus on both photos and respond for three minutes

In the first picture, you see a strong and courageous black female, bravely standing in front of two officers in protest. She is risking her life to do so. Iesha Evans is simply proving to the world she does NOT mean less because she is black … and yet officers are there to stop her. She did not step down. In the picture below, you see Kendall Jenner handing a police officer a Pepsi. Maybe this wouldn’t be a big deal, except this was Pepsi’s weak, pathetic, and outrageous excuse of a commercial that belittles the whole movement of people fighting for their lives.

I - Identify a word or phrase, underline it, then write about it for two minutes

A white, privileged female in place of a fighting black woman was asking for trouble. A struggle we are continuously fighting every day, and they make a mockery of it. “I know what will work! Here Mr. Police Officer! Drink some Pepsi!” As if. Pepsi made a fool of themselves, and now their already dwindling fan base continues to ever shrink smaller.

R - Reframe your thoughts by choosing a different word, then write about that for one minute

You don’t know privilege until it’s gone. You don’t know privilege while it’s there—but you can and will be made accountable and aware. Don’t use it for evil. You are not stupid. Use it to do something. Kendall could’ve NOT done the commercial. Kendall could’ve released another commercial standing behind a black woman. Anything!

Exchange - Remember to discuss how this connects to our school song project and our previous discussions?

This connects two ways - 1) We want to convey a strong message. Be powerful. Show who we are. And Pepsi definitely tried. … Which leads to the second connection. 2) Not mess up and offend anyone, as had the one alma mater had been linked to black minstrels. We want to be amazing, but we have to be smart and careful and make sure we include everyone who goes to our school and everyone who may go to our school.

As a final step, students read and annotate the full article and compare it to their initial response.

Using current events and critical-thinking strategies like FIRE writing helps create a learning space where thinking is the goal rather than a score on a multiple-choice assessment. Critical-thinking skills can cross over to any of students’ other courses and into life outside the classroom. After all, we as teachers want to help the whole student be successful, and critical thinking is an important part of navigating life after they leave our classrooms.

‘Before-Explore-Explain’

Patrick Brown is the executive director of STEM and CTE for the Fort Zumwalt school district in Missouri and an experienced educator and author :

Planning for critical thinking focuses on teaching the most crucial science concepts, practices, and logical-thinking skills as well as the best use of instructional time. One way to ensure that lessons maintain a focus on critical thinking is to focus on the instructional sequence used to teach.

Explore-before-explain teaching is all about promoting critical thinking for learners to better prepare students for the reality of their world. What having an explore-before-explain mindset means is that in our planning, we prioritize giving students firsthand experiences with data, allow students to construct evidence-based claims that focus on conceptual understanding, and challenge students to discuss and think about the why behind phenomena.

Just think of the critical thinking that has to occur for students to construct a scientific claim. 1) They need the opportunity to collect data, analyze it, and determine how to make sense of what the data may mean. 2) With data in hand, students can begin thinking about the validity and reliability of their experience and information collected. 3) They can consider what differences, if any, they might have if they completed the investigation again. 4) They can scrutinize outlying data points for they may be an artifact of a true difference that merits further exploration of a misstep in the procedure, measuring device, or measurement. All of these intellectual activities help them form more robust understanding and are evidence of their critical thinking.

In explore-before-explain teaching, all of these hard critical-thinking tasks come before teacher explanations of content. Whether we use discovery experiences, problem-based learning, and or inquiry-based activities, strategies that are geared toward helping students construct understanding promote critical thinking because students learn content by doing the practices valued in the field to generate knowledge.

An Issue of Equity

Meg Riordan, Ph.D., is the chief learning officer at The Possible Project, an out-of-school program that collaborates with youth to build entrepreneurial skills and mindsets and provides pathways to careers and long-term economic prosperity. She has been in the field of education for over 25 years as a middle and high school teacher, school coach, college professor, regional director of N.Y.C. Outward Bound Schools, and director of external research with EL Education:

Although critical thinking often defies straightforward definition, most in the education field agree it consists of several components: reasoning, problem-solving, and decisionmaking, plus analysis and evaluation of information, such that multiple sides of an issue can be explored. It also includes dispositions and “the willingness to apply critical-thinking principles, rather than fall back on existing unexamined beliefs, or simply believe what you’re told by authority figures.”

Despite variation in definitions, critical thinking is nonetheless promoted as an essential outcome of students’ learning—we want to see students and adults demonstrate it across all fields, professions, and in their personal lives. Yet there is simultaneously a rationing of opportunities in schools for students of color, students from under-resourced communities, and other historically marginalized groups to deeply learn and practice critical thinking.

For example, many of our most underserved students often spend class time filling out worksheets, promoting high compliance but low engagement, inquiry, critical thinking, or creation of new ideas. At a time in our world when college and careers are critical for participation in society and the global, knowledge-based economy, far too many students struggle within classrooms and schools that reinforce low-expectations and inequity.

If educators aim to prepare all students for an ever-evolving marketplace and develop skills that will be valued no matter what tomorrow’s jobs are, then we must move critical thinking to the forefront of classroom experiences. And educators must design learning to cultivate it.

So, what does that really look like?

Unpack and define critical thinking

To understand critical thinking, educators need to first unpack and define its components. What exactly are we looking for when we speak about reasoning or exploring multiple perspectives on an issue? How does problem-solving show up in English, math, science, art, or other disciplines—and how is it assessed? At Two Rivers, an EL Education school, the faculty identified five constructs of critical thinking, defined each, and created rubrics to generate a shared picture of quality for teachers and students. The rubrics were then adapted across grade levels to indicate students’ learning progressions.

At Avenues World School, critical thinking is one of the Avenues World Elements and is an enduring outcome embedded in students’ early experiences through 12th grade. For instance, a kindergarten student may be expected to “identify cause and effect in familiar contexts,” while an 8th grader should demonstrate the ability to “seek out sufficient evidence before accepting a claim as true,” “identify bias in claims and evidence,” and “reconsider strongly held points of view in light of new evidence.”

When faculty and students embrace a common vision of what critical thinking looks and sounds like and how it is assessed, educators can then explicitly design learning experiences that call for students to employ critical-thinking skills. This kind of work must occur across all schools and programs, especially those serving large numbers of students of color. As Linda Darling-Hammond asserts , “Schools that serve large numbers of students of color are least likely to offer the kind of curriculum needed to ... help students attain the [critical-thinking] skills needed in a knowledge work economy. ”

So, what can it look like to create those kinds of learning experiences?

Designing experiences for critical thinking

After defining a shared understanding of “what” critical thinking is and “how” it shows up across multiple disciplines and grade levels, it is essential to create learning experiences that impel students to cultivate, practice, and apply these skills. There are several levers that offer pathways for teachers to promote critical thinking in lessons:

1.Choose Compelling Topics: Keep it relevant

A key Common Core State Standard asks for students to “write arguments to support claims in an analysis of substantive topics or texts using valid reasoning and relevant and sufficient evidence.” That might not sound exciting or culturally relevant. But a learning experience designed for a 12th grade humanities class engaged learners in a compelling topic— policing in America —to analyze and evaluate multiple texts (including primary sources) and share the reasoning for their perspectives through discussion and writing. Students grappled with ideas and their beliefs and employed deep critical-thinking skills to develop arguments for their claims. Embedding critical-thinking skills in curriculum that students care about and connect with can ignite powerful learning experiences.

2. Make Local Connections: Keep it real

At The Possible Project , an out-of-school-time program designed to promote entrepreneurial skills and mindsets, students in a recent summer online program (modified from in-person due to COVID-19) explored the impact of COVID-19 on their communities and local BIPOC-owned businesses. They learned interviewing skills through a partnership with Everyday Boston , conducted virtual interviews with entrepreneurs, evaluated information from their interviews and local data, and examined their previously held beliefs. They created blog posts and videos to reflect on their learning and consider how their mindsets had changed as a result of the experience. In this way, we can design powerful community-based learning and invite students into productive struggle with multiple perspectives.

3. Create Authentic Projects: Keep it rigorous

At Big Picture Learning schools, students engage in internship-based learning experiences as a central part of their schooling. Their school-based adviser and internship-based mentor support them in developing real-world projects that promote deeper learning and critical-thinking skills. Such authentic experiences teach “young people to be thinkers, to be curious, to get from curiosity to creation … and it helps students design a learning experience that answers their questions, [providing an] opportunity to communicate it to a larger audience—a major indicator of postsecondary success.” Even in a remote environment, we can design projects that ask more of students than rote memorization and that spark critical thinking.

Our call to action is this: As educators, we need to make opportunities for critical thinking available not only to the affluent or those fortunate enough to be placed in advanced courses. The tools are available, let’s use them. Let’s interrogate our current curriculum and design learning experiences that engage all students in real, relevant, and rigorous experiences that require critical thinking and prepare them for promising postsecondary pathways.

Critical Thinking & Student Engagement

Dr. PJ Caposey is an award-winning educator, keynote speaker, consultant, and author of seven books who currently serves as the superintendent of schools for the award-winning Meridian CUSD 223 in northwest Illinois. You can find PJ on most social-media platforms as MCUSDSupe:

When I start my keynote on student engagement, I invite two people up on stage and give them each five paper balls to shoot at a garbage can also conveniently placed on stage. Contestant One shoots their shot, and the audience gives approval. Four out of 5 is a heckuva score. Then just before Contestant Two shoots, I blindfold them and start moving the garbage can back and forth. I usually try to ensure that they can at least make one of their shots. Nobody is successful in this unfair environment.

I thank them and send them back to their seats and then explain that this little activity was akin to student engagement. While we all know we want student engagement, we are shooting at different targets. More importantly, for teachers, it is near impossible for them to hit a target that is moving and that they cannot see.

Within the world of education and particularly as educational leaders, we have failed to simplify what student engagement looks like, and it is impossible to define or articulate what student engagement looks like if we cannot clearly articulate what critical thinking is and looks like in a classroom. Because, simply, without critical thought, there is no engagement.

The good news here is that critical thought has been defined and placed into taxonomies for decades already. This is not something new and not something that needs to be redefined. I am a Bloom’s person, but there is nothing wrong with DOK or some of the other taxonomies, either. To be precise, I am a huge fan of Daggett’s Rigor and Relevance Framework. I have used that as a core element of my practice for years, and it has shaped who I am as an instructional leader.

So, in order to explain critical thought, a teacher or a leader must familiarize themselves with these tried and true taxonomies. Easy, right? Yes, sort of. The issue is not understanding what critical thought is; it is the ability to integrate it into the classrooms. In order to do so, there are a four key steps every educator must take.

- Integrating critical thought/rigor into a lesson does not happen by chance, it happens by design. Planning for critical thought and engagement is much different from planning for a traditional lesson. In order to plan for kids to think critically, you have to provide a base of knowledge and excellent prompts to allow them to explore their own thinking in order to analyze, evaluate, or synthesize information.

- SIDE NOTE – Bloom’s verbs are a great way to start when writing objectives, but true planning will take you deeper than this.

QUESTIONING

- If the questions and prompts given in a classroom have correct answers or if the teacher ends up answering their own questions, the lesson will lack critical thought and rigor.

- Script five questions forcing higher-order thought prior to every lesson. Experienced teachers may not feel they need this, but it helps to create an effective habit.

- If lessons are rigorous and assessments are not, students will do well on their assessments, and that may not be an accurate representation of the knowledge and skills they have mastered. If lessons are easy and assessments are rigorous, the exact opposite will happen. When deciding to increase critical thought, it must happen in all three phases of the game: planning, instruction, and assessment.

TALK TIME / CONTROL

- To increase rigor, the teacher must DO LESS. This feels counterintuitive but is accurate. Rigorous lessons involving tons of critical thought must allow for students to work on their own, collaborate with peers, and connect their ideas. This cannot happen in a silent room except for the teacher talking. In order to increase rigor, decrease talk time and become comfortable with less control. Asking questions and giving prompts that lead to no true correct answer also means less control. This is a tough ask for some teachers. Explained differently, if you assign one assignment and get 30 very similar products, you have most likely assigned a low-rigor recipe. If you assign one assignment and get multiple varied products, then the students have had a chance to think deeply, and you have successfully integrated critical thought into your classroom.

Thanks to Dara, Patrick, Meg, and PJ for their contributions!

Please feel free to leave a comment with your reactions to the topic or directly to anything that has been said in this post.

Consider contributing a question to be answered in a future post. You can send one to me at [email protected] . When you send it in, let me know if I can use your real name if it’s selected or if you’d prefer remaining anonymous and have a pseudonym in mind.

You can also contact me on Twitter at @Larryferlazzo .

Education Week has published a collection of posts from this blog, along with new material, in an e-book form. It’s titled Classroom Management Q&As: Expert Strategies for Teaching .

Just a reminder; you can subscribe and receive updates from this blog via email (The RSS feed for this blog, and for all Ed Week articles, has been changed by the new redesign—new ones won’t be available until February). And if you missed any of the highlights from the first nine years of this blog, you can see a categorized list below.

- This Year’s Most Popular Q&A Posts

- Race & Racism in Schools

- School Closures & the Coronavirus Crisis

- Classroom-Management Advice

- Best Ways to Begin the School Year

- Best Ways to End the School Year

- Student Motivation & Social-Emotional Learning

- Implementing the Common Core

- Facing Gender Challenges in Education

- Teaching Social Studies

- Cooperative & Collaborative Learning

- Using Tech in the Classroom

- Student Voices

- Parent Engagement in Schools

- Teaching English-Language Learners

- Reading Instruction

- Writing Instruction

- Education Policy Issues

- Differentiating Instruction

- Math Instruction

- Science Instruction

- Advice for New Teachers

- Author Interviews

- Entering the Teaching Profession

- The Inclusive Classroom

- Learning & the Brain

- Administrator Leadership

- Teacher Leadership

- Relationships in Schools

- Professional Development

- Instructional Strategies

- Best of Classroom Q&A

- Professional Collaboration

- Classroom Organization

- Mistakes in Education

- Project-Based Learning

I am also creating a Twitter list including all contributors to this column .

The opinions expressed in Classroom Q&A With Larry Ferlazzo are strictly those of the author(s) and do not reflect the opinions or endorsement of Editorial Projects in Education, or any of its publications.

Sign Up for EdWeek Update

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

- Our Mission

Helping Students Hone Their Critical Thinking Skills

Used consistently, these strategies can help middle and high school teachers guide students to improve much-needed skills.

Critical thinking skills are important in every discipline, at and beyond school. From managing money to choosing which candidates to vote for in elections to making difficult career choices, students need to be prepared to take in, synthesize, and act on new information in a world that is constantly changing.

While critical thinking might seem like an abstract idea that is tough to directly instruct, there are many engaging ways to help students strengthen these skills through active learning.

Make Time for Metacognitive Reflection

Create space for students to both reflect on their ideas and discuss the power of doing so. Show students how they can push back on their own thinking to analyze and question their assumptions. Students might ask themselves, “Why is this the best answer? What information supports my answer? What might someone with a counterargument say?”

Through this reflection, students and teachers (who can model reflecting on their own thinking) gain deeper understandings of their ideas and do a better job articulating their beliefs. In a world that is go-go-go, it is important to help students understand that it is OK to take a breath and think about their ideas before putting them out into the world. And taking time for reflection helps us more thoughtfully consider others’ ideas, too.

Teach Reasoning Skills

Reasoning skills are another key component of critical thinking, involving the abilities to think logically, evaluate evidence, identify assumptions, and analyze arguments. Students who learn how to use reasoning skills will be better equipped to make informed decisions, form and defend opinions, and solve problems.

One way to teach reasoning is to use problem-solving activities that require students to apply their skills to practical contexts. For example, give students a real problem to solve, and ask them to use reasoning skills to develop a solution. They can then present their solution and defend their reasoning to the class and engage in discussion about whether and how their thinking changed when listening to peers’ perspectives.

A great example I have seen involved students identifying an underutilized part of their school and creating a presentation about one way to redesign it. This project allowed students to feel a sense of connection to the problem and come up with creative solutions that could help others at school. For more examples, you might visit PBS’s Design Squad , a resource that brings to life real-world problem-solving.

Ask Open-Ended Questions

Moving beyond the repetition of facts, critical thinking requires students to take positions and explain their beliefs through research, evidence, and explanations of credibility.

When we pose open-ended questions, we create space for classroom discourse inclusive of diverse, perhaps opposing, ideas—grounds for rich exchanges that support deep thinking and analysis.

For example, “How would you approach the problem?” and “Where might you look to find resources to address this issue?” are two open-ended questions that position students to think less about the “right” answer and more about the variety of solutions that might already exist.

Journaling, whether digitally or physically in a notebook, is another great way to have students answer these open-ended prompts—giving them time to think and organize their thoughts before contributing to a conversation, which can ensure that more voices are heard.

Once students process in their journal, small group or whole class conversations help bring their ideas to life. Discovering similarities between answers helps reveal to students that they are not alone, which can encourage future participation in constructive civil discourse.

Teach Information Literacy

Education has moved far past the idea of “Be careful of what is on Wikipedia, because it might not be true.” With AI innovations making their way into classrooms, teachers know that informed readers must question everything.

Understanding what is and is not a reliable source and knowing how to vet information are important skills for students to build and utilize when making informed decisions. You might start by introducing the idea of bias: Articles, ads, memes, videos, and every other form of media can push an agenda that students may not see on the surface. Discuss credibility, subjectivity, and objectivity, and look at examples and nonexamples of trusted information to prepare students to be well-informed members of a democracy.

One of my favorite lessons is about the Pacific Northwest tree octopus . This project asks students to explore what appears to be a very real website that provides information on this supposedly endangered animal. It is a wonderful, albeit over-the-top, example of how something might look official even when untrue, revealing that we need critical thinking to break down “facts” and determine the validity of the information we consume.

A fun extension is to have students come up with their own website or newsletter about something going on in school that is untrue. Perhaps a change in dress code that requires everyone to wear their clothes inside out or a change to the lunch menu that will require students to eat brussels sprouts every day.

Giving students the ability to create their own falsified information can help them better identify it in other contexts. Understanding that information can be “too good to be true” can help them identify future falsehoods.

Provide Diverse Perspectives

Consider how to keep the classroom from becoming an echo chamber. If students come from the same community, they may have similar perspectives. And those who have differing perspectives may not feel comfortable sharing them in the face of an opposing majority.

To support varying viewpoints, bring diverse voices into the classroom as much as possible, especially when discussing current events. Use primary sources: videos from YouTube, essays and articles written by people who experienced current events firsthand, documentaries that dive deeply into topics that require some nuance, and any other resources that provide a varied look at topics.

I like to use the Smithsonian “OurStory” page , which shares a wide variety of stories from people in the United States. The page on Japanese American internment camps is very powerful because of its first-person perspectives.

Practice Makes Perfect

To make the above strategies and thinking routines a consistent part of your classroom, spread them out—and build upon them—over the course of the school year. You might challenge students with information and/or examples that require them to use their critical thinking skills; work these skills explicitly into lessons, projects, rubrics, and self-assessments; or have students practice identifying misinformation or unsupported arguments.

Critical thinking is not learned in isolation. It needs to be explored in English language arts, social studies, science, physical education, math. Every discipline requires students to take a careful look at something and find the best solution. Often, these skills are taken for granted, viewed as a by-product of a good education, but true critical thinking doesn’t just happen. It requires consistency and commitment.

In a moment when information and misinformation abound, and students must parse reams of information, it is imperative that we support and model critical thinking in the classroom to support the development of well-informed citizens.

All of our Thinker's Guides are now published by Rowman and Littlefield Publishers. In this section, you find samples sections from each guide. For the full guides, visit Rowman and Littlefield, (rowman.com)

- The Miniature Guide to Critical Thinking Concepts & Tools

- The Thinker's Guide to Analytic Thinking

- The Thinker's Guide to the Human Mind

- The Thinker's Guide for Students on How to Study & Learn a Discipline

- The Thinker's Guide to Ethical Reasoning

- Student Guide to Historical Thinking

- The Aspiring Thinker's Guide to Critical Thinking

- How to Read a Paragraph: The Art of Close Reading

- How to Write a Paragraph: The Art of Substantive Writing

- A Glossary of Critical Thinking Terms and Concepts

- The Art of Asking Essential Questions

- The Nature and Functions of Critical & Creative Thinking

- The Thinker's Guide to Scientific Thinking

- Fact over Fake: A Critical Thinker's Guide to Media Bias and Political Propaganda

- The Thinker's Guide to Fallacies: The Art of Mental Trickery

- The Thinker's Guide to Clinical Reasoning

- The Thinker's Guide to Engineering Reasoning

- The Thinker's Guide to Intellectual Standards

- How to Improve Student Learning

- A Guide for Educators to Critical Thinking Competency Standards

- The Thinker's Guide to Socratic Questioning

- The International Critical Thinking Reading and Writing Test

- The Miniature Guide for Those Who Teach on Practical Ways to Promote Active & Cooperative Learning

- A Critical Thinker's Guide to Educational Fads

- Instructor's Guide to Historical Thinking

- From Argument and Philosophy to Critical Thinking Across the Curriculum

- Reflections on the Nature of Critical Thinking, Its History, Politics, and Barriers, and on Its Status across the College & University Curriculum Part I

- Reflections on the Nature of Critical Thinking, Its History, Politics, and Barriers, and on Its Status across the College & University Curriculum Part II

- Reflections on the Nature of Critical Thinking, Its History, Politics, and Barriers, and on Its Status across the College/University Curriculum Part I

- Reflections on the Nature of Critical Thinking, Its History, Politics, and Barriers, and on Its Status across the College/University Curriculum Part II

- Inquiry: Critical Thinking Across the Disciplines

- Mass Media and Critical Thinking: Reasoning for a Second-Hand World

- Critical Thinking and Emotional Intelligence

- Critical Thinking and Command of Language

- The Need For Comprehensiveness In Critical Thinking Instruction

- A "Third Wave" Manifesto: Keynotes of the Sonoma Conference

- Critical Thinking and the State of Education Today

- Thinking Critically About Identities

- Introductions to the Memorial Issue by Guest Editors Linda Elder and Gerald Nosich

- Richard Paul's Contributions to the Field of Critical Thinking Studies and to the Establishment of First Principles in Critical Thinking

- Richard Paul and the Philosophical Foundations of Critical Thinking

- Truth-seeking Versus Confirmation Bias: How Richard Paul's Conception of Critical Thinking Cultivates Authentic Research and Fairminded Thinking

- Portaging Richard Paul's Model to Professional Practice: Ideas that Integrate

- Richard Paul's Approach to Critical Thinking: Comprehensiveness, Systematicity, and Practicality

- Making a Campus-Wide Commitment to Critical Thinking: Insights and Promising Practices Utilizing the Paul-Elder Approach at the University of Louisville

- Defining Critical Thinking

- Critical Societies: Thoughts from the Past

- Sumner's Definition of Critical Thinking

- Our Concept and Definition of Critical Thinking

- Critical Thinking: Basic Questions & Answers

- A Brief History of the Idea of Critical Thinking

- Distinguishing Between Inert Information, Activated Ignorance, Activated Knowledge

- Critical Thinking: Identifying the Targets

- Distinguishing Between Inferences and Assumptions

- Critical Thinking Development: A Stage Theory

- Becoming a Critic of Your Thinking

- Bertrand Russell on Critical Thinking

- Content Is Thinking, Thinking is Content

- Critical Thinking in Every Domain of Knowledge and Belief

- Using Intellectual Standards to Assess Student Reasoning

- Open-Minded Inquiry

- Valuable Intellectual Traits

- Universal Intellectual Standards

- Thinking With Concepts

- The Role of Socratic Questioning in Thinking, Teaching, and Learning

- The Analysis & Assessment of Thinking

- Intellectual Foundations: The Key Missing Piece in School Restructuring

- Pseudo Critical Thinking in the Educational Establishment

- Research Findings and Policy Recommendations

- Why Students and Teachers Don't Reason Well

- Critical Thinking in the Engineering Enterprise: Novices Typically Don't Even Know What Questions to Ask

- Critical Thinking Movement: 3 Waves

- University of Louisville Faculty Speak About Critical Thinking QEP (Video)

- An Overview of How to Design Instruction Using Critical Thinking Concepts

- Recommendations for Departmental Self-Evaluation

- College-Wide Grading Standards

- Sample Course: American History: 1600 to 1800

- CT Class Syllabus

- Syllabus - Psychology I

- A Sample Assignment Format

- Grade Profiles

- Critical Thinking Class: Student Understandings

- Structures for Student Self-Assessment

- Critical Thinking Class: Grading Policies

- Socratic Teaching

- Critical Thinking and Nursing

- A Logic of an Introductory Business Ethics Course

- Radio Show and Podcast: Critical Thinking for Everyone!

- Teaching Tactics that Encourage Active Learning

- The Art of Redesigning Instruction

- Making Critical Thinking Intuitive

- Remodeled Lessons: K-3

- Remodeled Lessons: 4-6

- Remodeled Lessons: 6-9

- Remodeled Lessons: High School

- Strategy List: 35 Dimensions of Critical Thought

- Introduction to Remodeling: Components of Remodels and Their Functions

- John Stuart Mill: On Instruction, Intellectual Development, and Disciplined Learning

- Complex Interdisciplinary Questions Exemplified: Ecological Sustainability

- Newton, Darwin, & Einstein

- The Critical Mind is A Questioning Mind: Learning How to Ask Powerful, Probing Questions

- Three Categories of Questions: Crucial Distinctions

- Ethical Reasoning Essential to Education

- Ethics Without Indoctrination

- Engineering Reasoning

- Accelerating Change

- Critical Thinking, Moral Integrity and Citizenship

- Natural Egocentric Dispositions

- Diversity: Making Sense of It Through Critical Thinking

- Global Change: Why C.T. is Essential To the Community College Mission

- Applied Disciplines: A Critical Thinking Model for Engineering

- Critical Thinking in Everyday Life: 9 Strategies

- Developing as Rational Persons: Viewing Our Development in Stages

- How to Study and Learn (Part One)

- How to Study and Learn (Part Two)

- How to Study and Learn (Part Three)

- How to Study and Learn (Part Four)

- The Art of Close Reading (Part One)

- The Art of Close Reading (Part Two)

- The Art of Close Reading (Part Three)

- Looking To The Future With a Critical Eye: A Message for High School Graduates

- Becoming a Critic Of Your Thinking

- Reading Backwards: Classic Books Online

- Liberating the Mind: Overcoming Sociocentric Thought and Egocentric Tendencies

- The Miniature Guide to Critical Thinking for Children

- Fairminded Fran and the Three Small Black Community Cats

- Teacher's Manual Part 1 for the Miniature Guide to Critical Thinking for Children

- Teacher's Manual Part 2 for the Miniature Guide to Critical Thinking for Children

- Critical Thinking Handbook K-3rd Grades

- Teacher's Handbook for 'Critical Thinking for Children'

- Think About Fran & Sam

- Critical Thinking Handbook 4th-6th Grades

- Critical Thinking Handbook 6th-9th Grades

- Critical Thinking Handbook High School

- Critical Thinking - Basic Theory & Instructional Structures Handbook

- 1 Table of Contents

- 2 Garbage and Powerful Ideas

- 3 Elements and Standards

- 4 Questions

- 5 Socratic Questioning

- 6 Designing Structures

- 7 Content as Thinking

- 8 Affective Dimension of Thinking....Ego and Non

- 9 Where Do We Stand

- Card 1 - Teach for Depth of Understanding

- Card 2 - The Elements of Thought

- Card 3 - Questions for Socratic Dialogue

- Card 4 - Intellectual Standards

- Card 5 - Dimensions of Critical Thought

- Card 6 - Intellectual Virtues

- Poster 1 - Analysis of Thought

- Poster 2 - Intellectual Standards

- Poster 3 - Elements of Thought

- Poster 4 - Elements, Standards, and Traits

- Poster 5 - Parts of Thinking

- Chapter 1 - The Critical Thinking Movement in Historical Perspective

- Chapter 2 - Critical thinking Basic Questions and Answers

- Chapter 3 - The Logic of Creative and Critical Thinking

- Chapter 4 - Critical Thinking in North America

- Chapter 5 - Background Logic, Critical Thinking, and Irrational Language Games

- Chapter 6 - A Model for the National Assessment of Higher Order Thinking

- Chapter 7 - Using Intellectual Standards to Assess Student Reasoning

- Chapter 8 - Why Students - and Teachers - Don't Reason Well

- Chapter 9 - Critical Thinking Fundamentals to Education for a Free Society

- Chapter 10 - Critical Thinking and the Critical Person

- Chapter 11 - Critical Thinking and the Nature of Prejudice

- Chapter 12 - Ethics Without Indoctrination

- Chapter 13 - Critical Thinking, Moral Integrity, and Citizenship Teaching for the Intellectual Virtues

- Chapter 14 - Dialogical Thinking Critical Thinking Thought Essential to the Acquisition of Rational Knowledge and Passions

- Chapter 15 - Power, Vested Interest, and Prejudice On the Need for Critical Thinking in the Ethics of Social and Economic Development

- Chapter 16 - The Critical Connection Higher Order Thinking that Unifies Curriculum, Instruction, and Learning

- Chapter 17 - Dialogical and Dialectical Thinking

- Chapter 18 - The Art of Redesigning Instruction

- Chapter 19 - Using Critical Thinking to Identify National Bias in the News

- Chapter 20 - Socratic Questioning

- Chapter 21 - Strategies Thirty-Five Dimensions of Critical Thinking

- Chapter 22 - Critical Thinking in the Elementary Classroom

- Chapter 23 - Critical Thinking in Elementary Social Studies

- Chapter 24 - Critical Thinking in Elementary Language Arts

- Chapter 25 - Critical Thinking in Elementary Science

- Chapter 26 - Teaching Critical Thinking in the Strong Sense A Focus on Self-Deception, World Views, and a Dialectical Mode of Analysis

- Chapter 27 - Critical Thinking Staff Development The Lesson Plan Remodeling Approach

- Chapter 28 - The Greensboro Plan A Sample Staff Development Plan

- Chapter 29 - Critical Thinking and Learning Centers

- Chapter 30 - McPeck's Mistakes Why Critical Thinking Applies Across Disciplines and Domains

- Chapter 31 - Bloom's Taxonomy and Critical Thinking Instruction Recall is Not Knowledge

- Chapter 32 - Critical and Cultural Literacy Where E.D. Hirsch Goes Wrong

- Chapter 33 - Critical Thinking and General Semantics On the Primacy of Natural Languages

- Chapter 34 - Philosophy and Cognitive Psychology Contrasting Assumptions

- Chapter 35 - The Contribution of Philosophy to Thinking

- Chapter 36 - Critical Thinking and Social Studies

- Chapter 37 - Critical Thinking and Language Arts

- Chapter 38 - Critical Thinking and Science

- Chapter 39 - Critical Thinking, Human Development, and Rational Productivity

- Chapter 40 - What Critical Thinking Means to Me The Views of Teachers

- Chapter 41 - Glossary An Educators Guide to Critical Thinking Terms and Concepts

- Arabic - The Miniature Guide to Critical Thinking Concepts & Tools

- Bulgarian - The Miniature Guide to Critical Thinking Concepts & Tools

- French - Asking Questions

- French - Elements of Thought

- French - How Skilled Is Your Thinking

- French - Miniature Guide to Critical Thinking Concepts & Tools

- French - Miniature Guide to Critical Thinking for Children

- French - Scientific Thinking

- French - Stages of Development

- French - Strategic Thinking

- French - Thinker's Guide to Engineering Reasoning

- French - Tools for Taking Charge

- French - Universal Intellectual Standards

- German - Miniature Guide to Critical Thinking Concepts & Tools

- Persian - Miniature Guide to Critical Thinking Concepts & Tools

- Spanish - Miniature Guide to Critical Thinking Concepts & Tools

- Spanish - Active and Cooperative Learning

- Spanish - Critical Thinking Competency Standards

- Spanish - Miniature Guide to Critical Thinking for Children

- Spanish - Teacher's Manual to the Miniature Guide to Critical Thinking for Children

- Spanish - Thinker's Guide to Analytic Thinking

- Spanish - Thinker's Guide to Asking Essential Questions

- Spanish - Thinker's Guide to How to Improve Student Learning

- Spanish - Thinker's Guide to How to Read a Paragraph

- Spanish - Thinker's Guide to How to Study and Learn a Discipline

- Spanish - Thinker's Guide to How to Write a Paragraph

- Thai - Miniature Guide to Critical Thinking Concepts & Tools

- Thai - The Aspiring Thinker's Guide to Critical Thinking

- Turkish - Miniature Guide to Critical Thinking Concepts & Tools

- Turkish - Miniature Guide to Critical Thinking for Children

- Turkish - Thinker's Guide on How to Detect Media Bias and Propaganda

- Korean - Thinker's Guide to Analytic Thinking

- Korean - How to Read a Paragraph

- Korean - How to Write a Paragraph

- Persian - The Thinker's Guide to Clinical Reasoning

CTL Guide to the Critical Thinking Hub Area

Guidance for designing or teaching a Critical Thinking (CRT) course, including assignment resources and examples.

From the BU Hub Curriculum Guide

“The ability to think critically is the fundamental characteristic of an educated person. It is required for just, civil society and governance, prized by employers, and essential for the growth of wisdom. Critical thinking is what most people name first when asked about the essential components of a college education. From identifying and questioning assumptions, to weighing evidence before accepting an opinion or drawing a conclusion—all BU students will actively learn the habits of mind that characterize critical thinking, develop the self-discipline it requires, and practice it often, in varied contexts, across their education.” For more context around this Hub area, see this Hub page .

Learning Outcomes

Courses and cocurricular activities in this area must have all outcomes.

- Students will both gain critical thinking skills and be able to specify the components of critical thinking appropriate to a discipline or family of disciplines. These may include habits of distinguishing deductive from inductive modes of inference, methods of adjudicating disputes, recognizing common logical fallacies and cognitive biases, translating ordinary language into formal argument, distinguishing empirical claims about matters of fact from normative or evaluative judgments, and/or recognizing the ways in which emotional responses or cultural assumptions can affect reasoning processes.

- Drawing on skills developed in class, students will be able to critically evaluate, analyze, and generate arguments, bodies of evidence, and/or claims, including their own.

If you are proposing a CRT course or if you want to learn more about these outcomes, please see this Interpretive Document . Interpretive Documents, written by the General Education Committee , are designed to answer questions faculty have raised about Hub policies, practices, and learning outcomes as a part of the course approval process. To learn more about the proposal process, start here .

Area Specific Resources

- Richard Paul , Center for Critical Thinking ( criticalthinking.org ). Includes sample lessons, syllabi, teaching suggestions, and interdisciplinary resources and examples.

- John Bean ’s Engaging Ideas – The Professor’s Guide to integrating Writing, Critical Thinking, and Active learning in the Classroom is an invaluable resource for developing classroom activities and assignments that promote critical thinking and the scaffolding of writing.

Assignment Ideas

Weekly writing assignments.

These assignments are question-driven, thematic, and require students to integrate disciplinary and critical thinking literature to evaluate the validity of arguments in case studies, as well as the connections among method, theory, and practice in the case studies. Here, students are asked to utilize a chosen critical thinking framework throughout their written responses. These assignments can evolve during the semester by prompting students to address increasing complex case studies and arguments while also evaluating their own opinions using evidence from the readings. Along the way, students have ample opportunities for self-reflection, peer feedback, and coaching by the instructor.

Argument Mapping

A visual technique that allows students to analyze persuasive prose. This technique allows students to evaluate arguments–that is, distinguish valid from invalid arguments, and evaluate the soundness of different arguments. Advanced usage can help students organize and navigate complex information, encourage clearly articulated reasoning, and promote quick and effective communication. To learn more, please explore the following resources:

- Carnegie Mellon University’s Open Learning Initiative course on this topic provides an excellent i ntroduction to exploring and understanding arguments. The course explains what the parts of an argument are, how to break arguments into their component parts, and how to create diagrams to show how those parts relate to each other.

- Philmaps.com provides a handout that introduces the concept of argument mapping to students, and also includes a number of sample activities that faculty can use to introduce students to argument mapping.

- Mindmup’s Argument Visualization platform is an online mind map tool easily leveraged for creating argument maps.

Research Proposal and Final Research Paper

Demonstrates students’ ability to identify, distinguish, and assess ideological and evaluative claims and judgments about the selected research topic. Throughout the semester, students have the opportunity to practice their ability to evaluate the validity of arguments, including their own beliefs about the topic. Formative and summative assessments are provided to students at regular intervals and during each stage of the project.

Facilitating discussion that Presses Students for Accuracy and Expanded Reasoning . This resource is part of Harvard University’s Graduate School of Education “Instructional Moves” video series.

Additional sample assignments and assessments can be found throughout the selected Resources section located above.

Course Design Questions

As you are integrating critical thinking into your course, here are a few questions that you might consider:

- What framework/vocabulary/process do you use to teach the key elements of critical thinking in your course?

- What assigned readings or other materials do you use to teach critical thinking specifically?

- Do students have opportunities throughout the semester to apply and practice these skills and receive feedback?

- What graded assignments evaluate how well students can both identify the key elements of critical thinking and demonstrate their ability to evaluate the validity of arguments (including their own)?

You may also be interested in:

Thinking critically in college workshop, ctl guide to the teamwork/collaboration hub area, ctl guide to writing-intensive hub courses, ctl guide to the individual in community hub area, ctl guide to digital/multimedia expression, oral & signed communication hub guide, creativity/innovation hub guide, research and information literacy hub guide.

- Campus Life

- ...a student.

- ...a veteran.

- ...an alum.

- ...a parent.

- ...faculty or staff.

- Class Schedule

- Crisis Resources

- People Finder

- Change Password

UTC RAVE Alert

Critical thinking and problem-solving, jump to: , what is critical thinking, characteristics of critical thinking, why teach critical thinking.

- Teaching Strategies to Help Promote Critical Thinking Skills

References and Resources

When examining the vast literature on critical thinking, various definitions of critical thinking emerge. Here are some samples:

- "Critical thinking is the intellectually disciplined process of actively and skillfully conceptualizing, applying, analyzing, synthesizing, and/or evaluating information gathered from, or generated by, observation, experience, reflection, reasoning, or communication, as a guide to belief and action" (Scriven, 1996).

- "Most formal definitions characterize critical thinking as the intentional application of rational, higher order thinking skills, such as analysis, synthesis, problem recognition and problem solving, inference, and evaluation" (Angelo, 1995, p. 6).

- "Critical thinking is thinking that assesses itself" (Center for Critical Thinking, 1996b).

- "Critical thinking is the ability to think about one's thinking in such a way as 1. To recognize its strengths and weaknesses and, as a result, 2. To recast the thinking in improved form" (Center for Critical Thinking, 1996c).

Perhaps the simplest definition is offered by Beyer (1995) : "Critical thinking... means making reasoned judgments" (p. 8). Basically, Beyer sees critical thinking as using criteria to judge the quality of something, from cooking to a conclusion of a research paper. In essence, critical thinking is a disciplined manner of thought that a person uses to assess the validity of something (statements, news stories, arguments, research, etc.).

Back

Wade (1995) identifies eight characteristics of critical thinking. Critical thinking involves asking questions, defining a problem, examining evidence, analyzing assumptions and biases, avoiding emotional reasoning, avoiding oversimplification, considering other interpretations, and tolerating ambiguity. Dealing with ambiguity is also seen by Strohm & Baukus (1995) as an essential part of critical thinking, "Ambiguity and doubt serve a critical-thinking function and are a necessary and even a productive part of the process" (p. 56).

Another characteristic of critical thinking identified by many sources is metacognition. Metacognition is thinking about one's own thinking. More specifically, "metacognition is being aware of one's thinking as one performs specific tasks and then using this awareness to control what one is doing" (Jones & Ratcliff, 1993, p. 10 ).

In the book, Critical Thinking, Beyer elaborately explains what he sees as essential aspects of critical thinking. These are:

- Dispositions: Critical thinkers are skeptical, open-minded, value fair-mindedness, respect evidence and reasoning, respect clarity and precision, look at different points of view, and will change positions when reason leads them to do so.

- Criteria: To think critically, must apply criteria. Need to have conditions that must be met for something to be judged as believable. Although the argument can be made that each subject area has different criteria, some standards apply to all subjects. "... an assertion must... be based on relevant, accurate facts; based on credible sources; precise; unbiased; free from logical fallacies; logically consistent; and strongly reasoned" (p. 12).

- Argument: Is a statement or proposition with supporting evidence. Critical thinking involves identifying, evaluating, and constructing arguments.

- Reasoning: The ability to infer a conclusion from one or multiple premises. To do so requires examining logical relationships among statements or data.

- Point of View: The way one views the world, which shapes one's construction of meaning. In a search for understanding, critical thinkers view phenomena from many different points of view.

- Procedures for Applying Criteria: Other types of thinking use a general procedure. Critical thinking makes use of many procedures. These procedures include asking questions, making judgments, and identifying assumptions.

Oliver & Utermohlen (1995) see students as too often being passive receptors of information. Through technology, the amount of information available today is massive. This information explosion is likely to continue in the future. Students need a guide to weed through the information and not just passively accept it. Students need to "develop and effectively apply critical thinking skills to their academic studies, to the complex problems that they will face, and to the critical choices they will be forced to make as a result of the information explosion and other rapid technological changes" (Oliver & Utermohlen, p. 1 ).

As mentioned in the section, Characteristics of Critical Thinking , critical thinking involves questioning. It is important to teach students how to ask good questions, to think critically, in order to continue the advancement of the very fields we are teaching. "Every field stays alive only to the extent that fresh questions are generated and taken seriously" (Center for Critical Thinking, 1996a ).

Beyer sees the teaching of critical thinking as important to the very state of our nation. He argues that to live successfully in a democracy, people must be able to think critically in order to make sound decisions about personal and civic affairs. If students learn to think critically, then they can use good thinking as the guide by which they live their lives.

Teaching Strategies to Help Promote Critical Thinking

The 1995, Volume 22, issue 1, of the journal, Teaching of Psychology , is devoted to the teaching critical thinking. Most of the strategies included in this section come from the various articles that compose this issue.

- CATS (Classroom Assessment Techniques): Angelo stresses the use of ongoing classroom assessment as a way to monitor and facilitate students' critical thinking. An example of a CAT is to ask students to write a "Minute Paper" responding to questions such as "What was the most important thing you learned in today's class? What question related to this session remains uppermost in your mind?" The teacher selects some of the papers and prepares responses for the next class meeting.

- Cooperative Learning Strategies: Cooper (1995) argues that putting students in group learning situations is the best way to foster critical thinking. "In properly structured cooperative learning environments, students perform more of the active, critical thinking with continuous support and feedback from other students and the teacher" (p. 8).

- Case Study /Discussion Method: McDade (1995) describes this method as the teacher presenting a case (or story) to the class without a conclusion. Using prepared questions, the teacher then leads students through a discussion, allowing students to construct a conclusion for the case.

- Using Questions: King (1995) identifies ways of using questions in the classroom:

- Reciprocal Peer Questioning: Following lecture, the teacher displays a list of question stems (such as, "What are the strengths and weaknesses of...). Students must write questions about the lecture material. In small groups, the students ask each other the questions. Then, the whole class discusses some of the questions from each small group.

- Reader's Questions: Require students to write questions on assigned reading and turn them in at the beginning of class. Select a few of the questions as the impetus for class discussion.

- Conference Style Learning: The teacher does not "teach" the class in the sense of lecturing. The teacher is a facilitator of a conference. Students must thoroughly read all required material before class. Assigned readings should be in the zone of proximal development. That is, readings should be able to be understood by students, but also challenging. The class consists of the students asking questions of each other and discussing these questions. The teacher does not remain passive, but rather, helps "direct and mold discussions by posing strategic questions and helping students build on each others' ideas" (Underwood & Wald, 1995, p. 18 ).

- Use Writing Assignments: Wade sees the use of writing as fundamental to developing critical thinking skills. "With written assignments, an instructor can encourage the development of dialectic reasoning by requiring students to argue both [or more] sides of an issue" (p. 24).

- Written dialogues: Give students written dialogues to analyze. In small groups, students must identify the different viewpoints of each participant in the dialogue. Must look for biases, presence or exclusion of important evidence, alternative interpretations, misstatement of facts, and errors in reasoning. Each group must decide which view is the most reasonable. After coming to a conclusion, each group acts out their dialogue and explains their analysis of it.

- Spontaneous Group Dialogue: One group of students are assigned roles to play in a discussion (such as leader, information giver, opinion seeker, and disagreer). Four observer groups are formed with the functions of determining what roles are being played by whom, identifying biases and errors in thinking, evaluating reasoning skills, and examining ethical implications of the content.

- Ambiguity: Strohm & Baukus advocate producing much ambiguity in the classroom. Don't give students clear cut material. Give them conflicting information that they must think their way through.

- Angelo, T. A. (1995). Beginning the dialogue: Thoughts on promoting critical thinking: Classroom assessment for critical thinking. Teaching of Psychology, 22(1), 6-7.

- Beyer, B. K. (1995). Critical thinking. Bloomington, IN: Phi Delta Kappa Educational Foundation.

- Center for Critical Thinking (1996a). The role of questions in thinking, teaching, and learning. [On-line]. Available HTTP: http://www.criticalthinking.org/University/univlibrary/library.nclk

- Center for Critical Thinking (1996b). Structures for student self-assessment. [On-line]. Available HTTP: http://www.criticalthinking.org/University/univclass/trc.nclk

- Center for Critical Thinking (1996c). Three definitions of critical thinking [On-line]. Available HTTP: http://www.criticalthinking.org/University/univlibrary/library.nclk

- Cooper, J. L. (1995). Cooperative learning and critical thinking. Teaching of Psychology, 22(1), 7-8.

- Jones, E. A. & Ratcliff, G. (1993). Critical thinking skills for college students. National Center on Postsecondary Teaching, Learning, and Assessment, University Park, PA. (Eric Document Reproduction Services No. ED 358 772)

- King, A. (1995). Designing the instructional process to enhance critical thinking across the curriculum: Inquiring minds really do want to know: Using questioning to teach critical thinking. Teaching of Psychology, 22 (1) , 13-17.

- McDade, S. A. (1995). Case study pedagogy to advance critical thinking. Teaching Psychology, 22(1), 9-10.

- Oliver, H. & Utermohlen, R. (1995). An innovative teaching strategy: Using critical thinking to give students a guide to the future.(Eric Document Reproduction Services No. 389 702)

- Robertson, J. F. & Rane-Szostak, D. (1996). Using dialogues to develop critical thinking skills: A practical approach. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 39(7), 552-556.

- Scriven, M. & Paul, R. (1996). Defining critical thinking: A draft statement for the National Council for Excellence in Critical Thinking. [On-line]. Available HTTP: http://www.criticalthinking.org/University/univlibrary/library.nclk

- Strohm, S. M., & Baukus, R. A. (1995). Strategies for fostering critical thinking skills. Journalism and Mass Communication Educator, 50 (1), 55-62.

- Underwood, M. K., & Wald, R. L. (1995). Conference-style learning: A method for fostering critical thinking with heart. Teaching Psychology, 22(1), 17-21.

- Wade, C. (1995). Using writing to develop and assess critical thinking. Teaching of Psychology, 22(1), 24-28.

Other Reading

- Bean, J. C. (1996). Engaging ideas: The professor's guide to integrating writing, critical thinking, & active learning in the classroom. Jossey-Bass.

- Bernstein, D. A. (1995). A negotiation model for teaching critical thinking. Teaching of Psychology, 22(1), 22-24.

- Carlson, E. R. (1995). Evaluating the credibility of sources. A missing link in the teaching of critical thinking. Teaching of Psychology, 22(1), 39-41.

- Facione, P. A., Sanchez, C. A., Facione, N. C., & Gainen, J. (1995). The disposition toward critical thinking. The Journal of General Education, 44(1), 1-25.

- Halpern, D. F., & Nummedal, S. G. (1995). Closing thoughts about helping students improve how they think. Teaching of Psychology, 22(1), 82-83.

- Isbell, D. (1995). Teaching writing and research as inseparable: A faculty-librarian teaching team. Reference Services Review, 23(4), 51-62.

- Jones, J. M. & Safrit, R. D. (1994). Developing critical thinking skills in adult learners through innovative distance learning. Paper presented at the International Conference on the practice of adult education and social development. Jinan, China. (Eric Document Reproduction Services No. ED 373 159)

- Sanchez, M. A. (1995). Using critical-thinking principles as a guide to college-level instruction. Teaching of Psychology, 22(1), 72-74.

- Spicer, K. L. & Hanks, W. E. (1995). Multiple measures of critical thinking skills and predisposition in assessment of critical thinking. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Speech Communication Association, San Antonio, TX. (Eric Document Reproduction Services No. ED 391 185)

- Terenzini, P. T., Springer, L., Pascarella, E. T., & Nora, A. (1995). Influences affecting the development of students' critical thinking skills. Research in Higher Education, 36(1), 23-39.

On the Internet

- Carr, K. S. (1990). How can we teach critical thinking. Eric Digest. [On-line]. Available HTTP: http://ericps.ed.uiuc.edu/eece/pubs/digests/1990/carr90.html

- The Center for Critical Thinking (1996). Home Page. Available HTTP: http://www.criticalthinking.org/University/

- Ennis, Bob (No date). Critical thinking. [On-line], April 4, 1997. Available HTTP: http://www.cof.orst.edu/cof/teach/for442/ct.htm

- Montclair State University (1995). Curriculum resource center. Critical thinking resources: An annotated bibliography. [On-line]. Available HTTP: http://www.montclair.edu/Pages/CRC/Bibliographies/CriticalThinking.html

- No author, No date. Critical Thinking is ... [On-line], April 4, 1997. Available HTTP: http://library.usask.ca/ustudy/critical/

- Sheridan, Marcia (No date). Internet education topics hotlink page. [On-line], April 4, 1997. Available HTTP: http://sun1.iusb.edu/~msherida/topics/critical.html

Walker Center for Teaching and Learning

- 433 Library

- Dept 4354

- 615 McCallie Ave

- 423-425-4188

8 Of The Most Important Critical Thinking Skills

The most important critical thinking skills include analysis, synthesis, interpretation, inferencing, and judgement.

Bertrand Russell’s 10 Essential Rules Of Critical Thinking

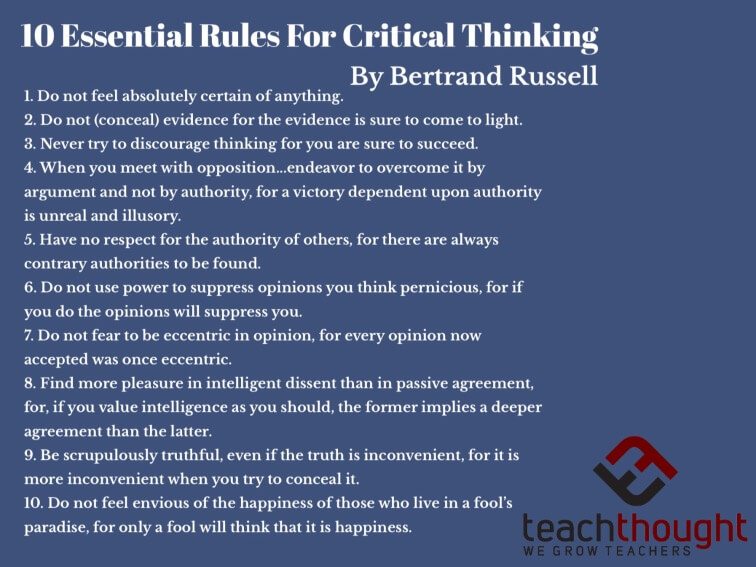

Bertrand Russell’s essential rules of critical thinking: #1. Do not feel absolutely certain of anything.

An Updated Guide To Questioning In The Classroom

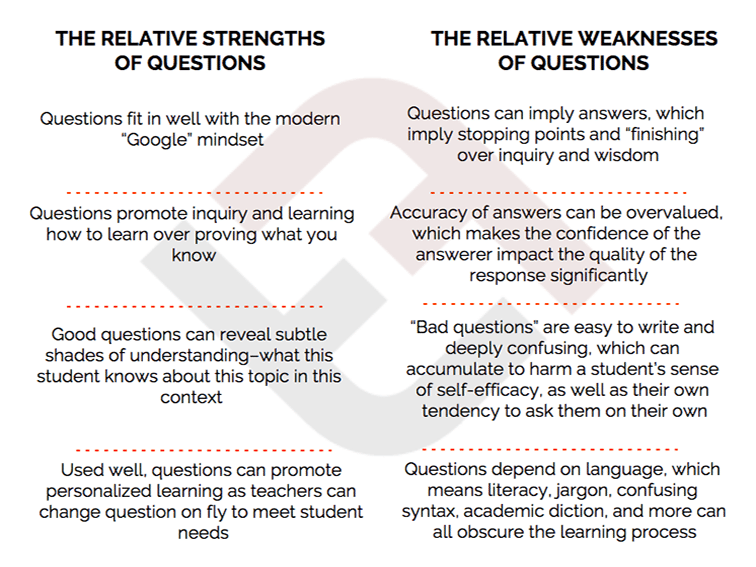

This guide to questioning in the classroom views questions as signs of understanding, not ignorance–the ability to see what you’re missing.

Richard Feynman On Knowing Versus Understanding

“A philosophy…sometimes called an understanding of the law…is a way that a person holds the laws…to guess quickly at consequences.”

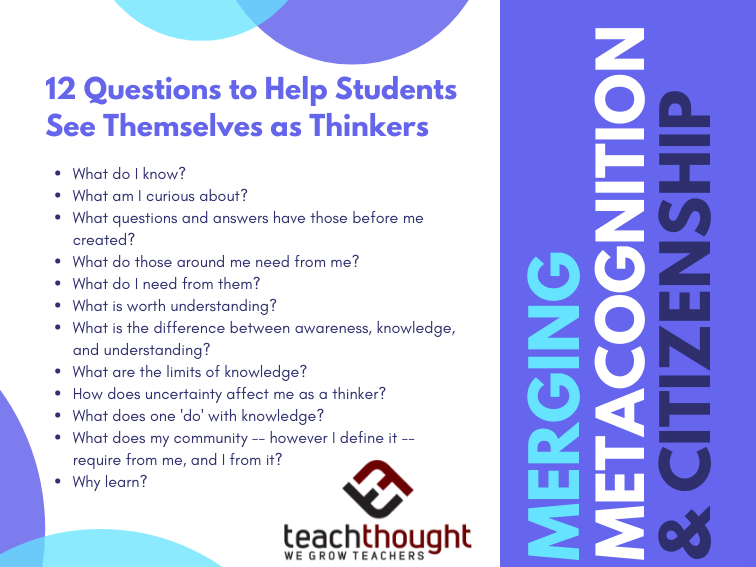

12 Questions To Help Students See Themselves As Thinkers

Self-knowledge is formed through metacognition and basic epistemology. Here are 12 questions to help students see themselves as thinkers.v

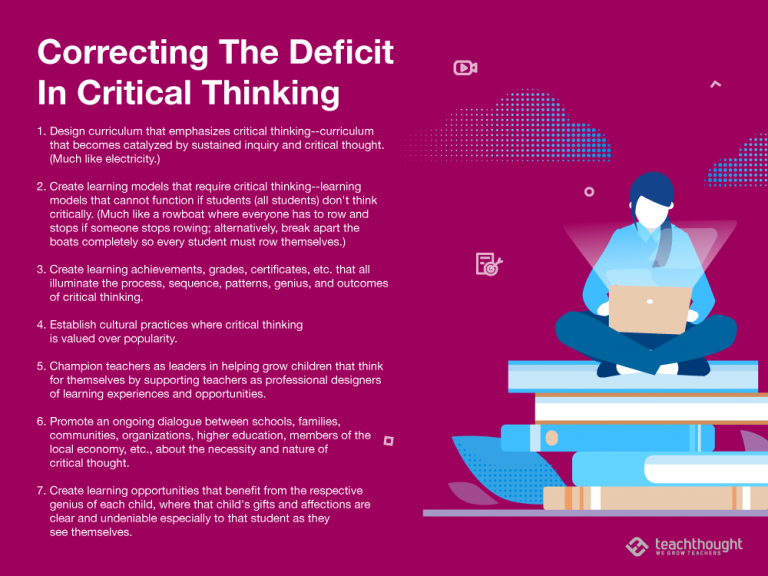

Correcting The Deficit In Critical Thinking

We can address a deficit of critical thinking by embedding into the architecture of education. This can be accomplished in any number of ways.

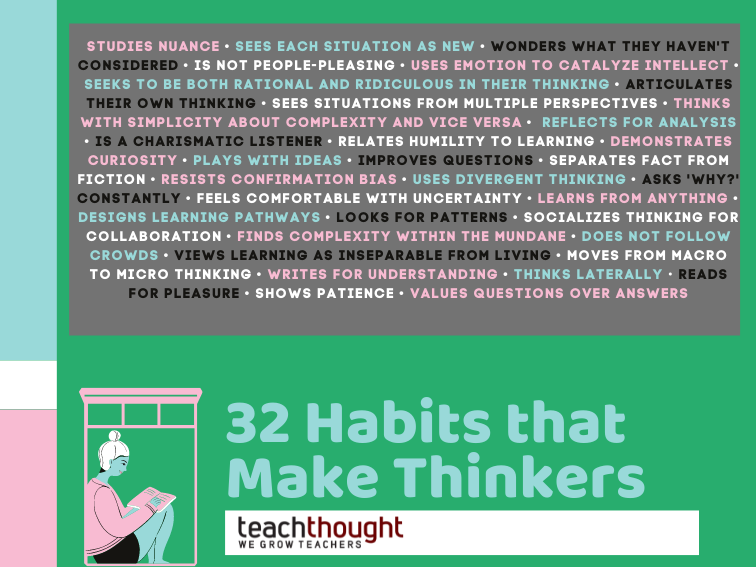

32 Habits That Make Thinkers

These 32 habits that make thinkers can lead to that critical shift that moves students from mere students to learners who think critically.

20 Of The Best Quotes About Knowledge

“Our knowledge of the world instructs us first of all that the world is greater than our knowledge of it.” –Wendell Berry

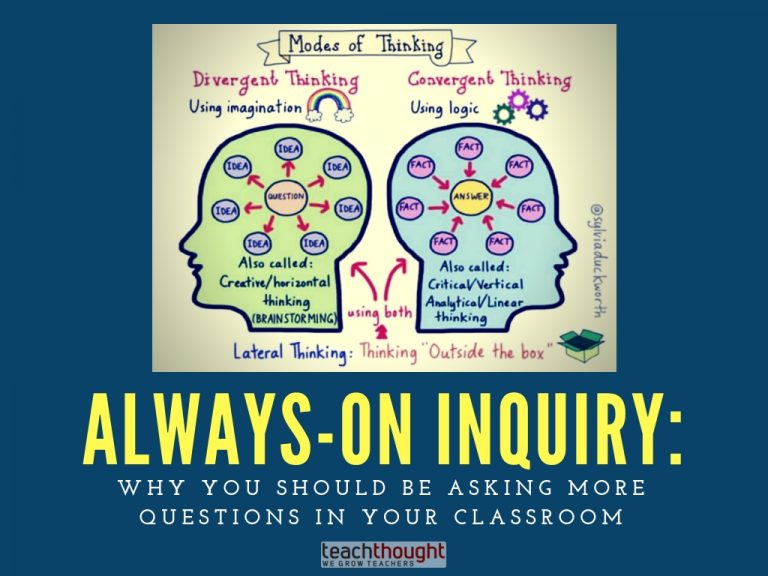

Why You Should Be Asking More Questions In Your Classroom

Teaching students to ask good questions engages them & acts as ongoing assessment. Here are some of the benefits of inquiry-based learning.

What Does ‘Critical Thinking’ Mean?

Critical thinking is the suspension of judgment while identifying biases and underlying assumptions in order to draw accurate conclusions.

50 Of The Most Inspirational Quotes About Life

“Every act of perception is to some degree an act of creation, and every act of memory is to some degree an act of imagination.”

25 Critical Thinking Apps For Extended Student Learning

Critical thinking is widely misunderstood. Apps that promote it can be hard to find. Here are 25 critical thinking apps to get you started.

End of content

- What's New?

- Interactive Sampler

- Scope and Sequence

- About the Authors

- Foundations

- Vocabulary Index

- Speaking Rubrics

- Independent Student Handbook

- Index of Exam Skills and Tasks

- Writing Rubrics

- Index of Skills and Exams

- Coming Soon

- Placement Test Audio

- Placement Test Documents

- Teacher's Book

- Video Scripts

- Teacher's Guide

- Audio Scripts

- ExamView Test Center

- Pacing Guide

- Teacher's Guide and Answer Key

- Vocabulary Extension Answer Key

Pathways: Listening, Speaking, and Critical Thinking

Pathways Listening, Speaking, and Critical Thinking, Second Edition uses compelling National Geographic stories, photos, video, and infographics to bring the world to the classroom. Authentic, relevant content and carefully sequenced lessons engage learners while equipping them with the skills needed for academic success.

NEW in Pathways Listening, Speaking, and Critical Thinking :

- Explicit instruction and practice of note-taking, listening, speaking, grammar, vocabulary, and pronunciation develop language proficiency and build academic skills.

- Slide shows of lectures and presentations enhance listening activities and develop presentation skills.

- Exam-style tasks prepare students for a range of international exams, including TOEFL and IELTS.

Ask the publishers to restore access to 500,000+ books.

Can You Chip In? (USD)

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

Pathways 3 : listening, speaking, and critical thinking ; teacher's guide

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

![[WorldCat (this item)] [WorldCat (this item)]](https://archive.org/images/worldcat-small.png)

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

2,076 Previews

5 Favorites

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

No suitable files to display here.

PDF access not available for this item.

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by station65.cebu on January 27, 2022