Theresa Smith Writes

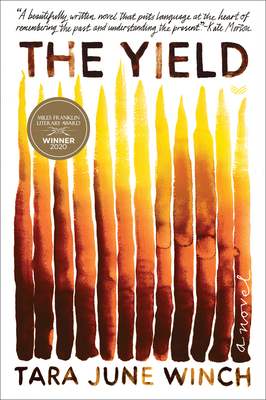

Delighting in all things bookish, book review: the yield by tara june winch, the yield…, about the book:.

Winner of the 2020 Miles Franklin Literary Award. Shortlisted for the VPLA. Winner, Book of the Year, People’s Choice, Christina Stead Prize for Fiction at NSW Premier’s Literary Award. Shortlisted for the Stella Prize.

The yield in English is the reaping, the things that man can take from the land. In the language of the Wiradjuri yield is the things you give to, the movement, the space between things: baayanha .

Knowing that he will soon die, Albert ‘Poppy’ Gondiwindi takes pen to paper. His life has been spent on the banks of the Murrumby River at Prosperous House, on Massacre Plains. Albert is determined to pass on the language of his people and everything that was ever remembered. He finds the words on the wind.

August Gondiwindi has been living on the other side of the world for ten years when she learns of her grandfather’s death. She returns home for his burial, wracked with grief and burdened with all she tried to leave behind. Her homecoming is bittersweet as she confronts the love of her kin and news that Prosperous is to be repossessed by a mining company. Determined to make amends she endeavours to save their land – a quest that leads her to the voice of her grandfather and into the past, the stories of her people, the secrets of the river.

Profoundly moving and exquisitely written, Tara June Winch’s The Yield is the story of a people and a culture dispossessed. But it is as much a celebration of what was and what endures, and a powerful reclaiming of Indigenous language, storytelling and identity.

My Thoughts:

This is a novel that I feel is best deeply contemplated rather than extensively commented on. It’s no surprise to me, now that I’ve read it, that it has been the recipient of such critical acclaim and the winner of more than one prestigious award. It is a brilliant novel: deeply thought provoking, challenging, intelligent, sophisticated in style, and beautifully written, despite the brutality and sorrow that the history, and narrative, is awash with.

There are three stories unfolding within this novel, the links between all three becoming firmer as the novel progresses. I enjoyed each section equally, to me, they each offered a lens of insight that taught me something. This may be a work of fiction, but it is insightful and informed by reality. August’s sections were drenched with sorrow, loss and grief, and yet, there was a hopeful glimmer, growing brighter as the novel approached its conclusion. What I really took away from August’s story though is the weight of intergenerational pain, and I feel I’ve gained a greater understanding about the importance of language and place within the context of cultural identity.

Reverend Greenleaf’s sections were fascinating to me on account of their historical significance, and I’ve long been interested in the history of missions and missionaries. We see here, that fine line between helping and inciting suffering. There is a lot of horrific history woven into these sections and Australia does not come off favourably. I do believe that Greenleaf’s intentions were good, but that didn’t mean that he did good through his actions. He suffered a lot himself for all that he did, and was also on the receiving end of prejudice on account of his German heritage. Anyone who doubts that slavery existed within Australia’s history would do well to read this novel.

And then we have Poppy’s dictionary, the jewel of this novel. I loved this dictionary so much. A mix of dreamtime stories with Poppy’s own history, this was just brilliantly done. I learnt so much from these sections and I really think this novel should be compulsory reading for all Australians – if such a thing existed. I’ll leave you with a few of Poppy’s dictionary entries. There were so many I loved, but this will give you a solid feel for the novel.

yield, bend the feet, tread, as in walking, also long, tall – baayanha Yield itself is a funny word – yield in English is the reaping, the things that man can take from the land, the thing he’s waited for and gets to claim. A wheat yield. In my language it’s the things you give to, the movement, the space between things. It’s also the action made by Baiame because sorrow, old age and pain bend and yield. The bodies of the ones that had passed were buried with every joint bent, even if the bones had to be broken. I think it was a bend in humiliation just like we bend at our knees and bow our heads. Bend, yield – baayanha . gaol, shut place – ngunba-ngidyala When your own daughter and then your grandson get put in gaol it must make the family look like trouble, I’m sure. But it isn’t so simple. Both Jolene and Joey made mistakes but the punishments outweighed the crimes. As much as the government wants to convince the population otherwise, it is an old thinking – locking us up as a solution. I think in this country there are divisions that run further than the songlines. The closed place, the shut place – the ngunba-ngidyala – is first built in the mind, and then it spreads. ashamed, have shame – giyal-dhuray I’m done with this word. I’d leave it out completely but I can’t. It’s become part of the dictionary we think we should carry. We mustn’t anymore. See, pain travels through our family tree like a songline. We’ve been singing our pain into a solid thing. The old ones, the young ones too, are ready to heal. We don’t have to be giyal-dhuray anymore, we don’t have to pass that down anymore.

About the Author:

Tara June Winch is a Wiradjuri author, born in Australia in 1983 and based in France. Her first novel, Swallow the Air was critically acclaimed. She was named a Sydney Morning Herald Best Young Australian Novelist, and has won numerous literary awards for Swallow the Air. A 10th Anniversary edition was published in 2016. In 2008, Tara was mentored by Nobel Prize winner Wole Soyinka as part of the prestigious Rolex Mentor and Protégé Arts Initiative. Her second book, the story collection After the Carnage was published in 2016. After the Carnage was longlisted for the Victorian Premier’s Literary Award for fiction, shortlisted for the 2017 NSW Premier’s Christina Stead prize for Fiction and the Queensland Literary Award for a collection. She wrote the Indigenous dance documentary, Carriberrie, which screened at the 71st Cannes Film Festival and toured internationally.

The Yield Published by Penguin Random House Australia Released 2nd July 2019

Share this:

6 thoughts on “ book review: the yield by tara june winch ”.

This is destined to be a classic of Australian literature IMO. I bet it’s making its way onto school reading lists…

Like Liked by 1 person

I really hope so. It has so much to offer.

I’m glad you got so much out of this too Theresa. As you say, the dictionary is the stand out feature of this story &, I’m sure, a big part of why it’s winning awards. I’m astounded that we are still not learning any Indigenous languages at school, or like Wales, use bilingual signs in local communities.

At the start of this year, the school where I work has an opening assembly where the senior students are all ‘invested’ as Year 12. Our Indigenous School Captain (that’s her actual title, we have three school captains and one is titled as Indigenous and has additional ‘Indigenous’ duties attached) gave the Welcome to Country in her Indigenous language. It was terrific, but this is the first time I’ve ever heard it spoken in real life and it was certainly the first time this has happened within that context. When you read a book like this that draws such a clear line from language to cultural identity, it is awful, so detrimental, that it’s not a part of every day life, like you indicate.

It’s a deceptively complex book, isn’t it? So many layers. When I reviewed it, I didn’t even touch on the Rev Greenleaf parts! (obviously important, but so many layers to the story, I couldn’t cover them all). The dictionary is the standout – each entry a story within a story. As Lisa said, I’m sure it will be a fixture on reading lists over the coming years.

The Rev Greenleaf parts were of particular interest to me, given my leanings towards history, so they stuck in my mind. I agree with you, deceptively complex! But also, which surprised me, easy to read. In the way that prize winners sometimes aren’t.

Leave a comment Cancel reply

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

Tara June Winch

352 pages, Hardcover

First published July 2, 2019

About the author

Ratings & Reviews

What do you think? Rate this book Write a Review

Friends & Following

Community reviews.

queen bee, bee—darribun, ngaraang The ngaraang is in danger now, whole colonies are dying and the queen bee darribun is left, like on a chessboard, without any pawns, with all the worker ngaraang dying off. The bee puts off leaving the hive until later in their lives, when they are adults, because with less flowers it means collecting pollen is hard work for the bee, and many die of exhaustion before they make honey—warrul—and never return to the home. If the pesticides from the farms stress the hive or the bees while they are out foraging in a big sweep, they can die. This triggers a very fast, too-early maturation of the next generation of bees, and they leave the hive too early, before they’re ready, and a whole colony collapses. The Gondiwindi have been like that, scattered children without the thing that nourishes them, without a compass to get back home.

yield, bend the feet, tread, as in walking, also long, tall—baayanha Yield itself is a funny word—yield in English is the reaping, the things that man can take from the land, the thing he’s waited for and gets to claim. A wheat yield. In my language it’s the things you give to, the movement, the space between things. It’s also the action made by Baiame, because sorrow, old age, and pain bend and yield. The bodies of the ones that had passed were buried with every joint bent, even if the bones had to be broken. I think it was a bend in humiliation, just like we bend at our knees and bow our heads. Bend, yield—baayanha.

The smells, tastes, and burdens left August. She ate again too; she wasn’t ngarran anymore. English changed their tongues, the formation of their minds, August thought—she’d drifted in and out of herself all that time. The language was the poem she had looked for, communicating what English failed to say. She’d come across the Pink Map and arrived. Her poppy used to say the words were paramount. That they were like icebergs floating, melting, that there were ocean depths to them that they couldn’t have talked about.

Join the discussion

Can't find what you're looking for.

- ADMIN AREA MY BOOKSHELF MY DASHBOARD MY PROFILE SIGN OUT SIGN IN

by Tara June Winch ‧ RELEASE DATE: June 2, 2020

A story woven from profound, overlooked historical material that’s sadly marred by sloppy execution.

An Aboriginal woman uncovers her heritage, and her painful past, to save her family’s home.

August Gondiwindi, a dishwasher in London, receives word that her grandfather Poppy Albert has died and knows she must return to Massacre Plains, the small Australian town her family has lived in for generations—a place she hasn’t visited in years: “Go back full with shame for having left, catch the disappointment in their turned mouths, go back and try to find all the things that she couldn’t find so many thousands of kilometres away.” She arrives at the family farm, Prosperous House, and as she helps her grandmother Elsie prepare food and clean for the large collection of aunts and uncles gathering for the funeral, she runs into former classmates and old flames and wrestles with her long-dormant grief at the disappearance of her sister, Jedda, who vanished when August was 9 and Jedda, 10. She also discovers that this may be the last time she sees her childhood home—her grandmother will soon be forced out of Prosperous House because a company plans to open a large tin mine on the land. Interwoven with August’s story are two other narrative strands: a lengthy letter from the Rev. Ferdinand Greenleaf, who founded the mission that eventually became Prosperous House to “build a home of safety for the poor waifs and strays,” and sections from a dictionary Poppy Albert was compiling of their family’s native language before his death, which includes words from the author’s ancestral Wiradjuri language. Albert’s entries are easily the most charming parts of the book. “The dictionary is not just words—there are little stories in those pages too,” he writes, and the same is true for his own effort, which weaves in reminiscences of meeting Elsie, fond memories of raising Jedda and August, and stories from his ancestors. But August’s chapters suffer from a lack of clarity; it’s often difficult to understand why events are significant, especially in the novel’s more dramatic latter half. Too often, it’s simply that the sentences are bewildering: “When the previous evening, like a virus, the true rumour that Rinepalm Mining had set an open day at the town hall filtered into the Valley, and back streets, the men and women, though on the edge of heatstroke, leapt from their houses and headed into town.”

Pub Date: June 2, 2020

ISBN: 978-0-06-300346-0

Page Count: 352

Publisher: HarperVia

Review Posted Online: March 28, 2020

Kirkus Reviews Issue: April 15, 2020

LITERARY FICTION | GENERAL FICTION

Share your opinion of this book

Awards & Accolades

Our Verdict

New York Times Bestseller

by Kristin Hannah ‧ RELEASE DATE: Feb. 6, 2024

A dramatic, vividly detailed reconstruction of a little-known aspect of the Vietnam War.

A young woman’s experience as a nurse in Vietnam casts a deep shadow over her life.

When we learn that the farewell party in the opening scene is for Frances “Frankie” McGrath’s older brother—“a golden boy, a wild child who could make the hardest heart soften”—who is leaving to serve in Vietnam in 1966, we feel pretty certain that poor Finley McGrath is marked for death. Still, it’s a surprise when the fateful doorbell rings less than 20 pages later. His death inspires his sister to enlist as an Army nurse, and this turn of events is just the beginning of a roller coaster of a plot that’s impressive and engrossing if at times a bit formulaic. Hannah renders the experiences of the young women who served in Vietnam in all-encompassing detail. The first half of the book, set in gore-drenched hospital wards, mildewed dorm rooms, and boozy officers’ clubs, is an exciting read, tracking the transformation of virginal, uptight Frankie into a crack surgical nurse and woman of the world. Her tensely platonic romance with a married surgeon ends when his broken, unbreathing body is airlifted out by helicopter; she throws her pent-up passion into a wild affair with a soldier who happens to be her dead brother’s best friend. In the second part of the book, after the war, Frankie seems to experience every possible bad break. A drawback of the story is that none of the secondary characters in her life are fully three-dimensional: Her dismissive, chauvinistic father and tight-lipped, pill-popping mother, her fellow nurses, and her various love interests are more plot devices than people. You’ll wish you could have gone to Vegas and placed a bet on the ending—while it’s against all the odds, you’ll see it coming from a mile away.

Pub Date: Feb. 6, 2024

ISBN: 9781250178633

Page Count: 480

Publisher: St. Martin's

Review Posted Online: Nov. 4, 2023

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Dec. 1, 2023

FAMILY LIFE & FRIENDSHIP | GENERAL FICTION | HISTORICAL FICTION

More by Kristin Hannah

BOOK REVIEW

by Kristin Hannah

More About This Book

PERSPECTIVES

BOOK TO SCREEN

SEEN & HEARD

IT STARTS WITH US

by Colleen Hoover ‧ RELEASE DATE: Oct. 18, 2022

Through palpable tension balanced with glimmers of hope, Hoover beautifully captures the heartbreak and joy of starting over.

The sequel to It Ends With Us (2016) shows the aftermath of domestic violence through the eyes of a single mother.

Lily Bloom is still running a flower shop; her abusive ex-husband, Ryle Kincaid, is still a surgeon. But now they’re co-parenting a daughter, Emerson, who's almost a year old. Lily won’t send Emerson to her father’s house overnight until she’s old enough to talk—“So she can tell me if something happens”—but she doesn’t want to fight for full custody lest it become an expensive legal drama or, worse, a physical fight. When Lily runs into Atlas Corrigan, a childhood friend who also came from an abusive family, she hopes their friendship can blossom into love. (For new readers, their history unfolds in heartfelt diary entries that Lily addresses to Finding Nemo star Ellen DeGeneres as she considers how Atlas was a calming presence during her turbulent childhood.) Atlas, who is single and running a restaurant, feels the same way. But even though she’s divorced, Lily isn’t exactly free. Behind Ryle’s veneer of civility are his jealousy and resentment. Lily has to plan her dates carefully to avoid a confrontation. Meanwhile, Atlas’ mother returns with shocking news. In between, Lily and Atlas steal away for romantic moments that are even sweeter for their authenticity as Lily struggles with child care, breastfeeding, and running a business while trying to find time for herself.

Pub Date: Oct. 18, 2022

ISBN: 978-1-668-00122-6

Publisher: Atria

Review Posted Online: July 26, 2022

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Aug. 15, 2022

ROMANCE | CONTEMPORARY ROMANCE | GENERAL ROMANCE | GENERAL FICTION

More by Colleen Hoover

by Colleen Hoover

- Discover Books Fiction Thriller & Suspense Mystery & Detective Romance Science Fiction & Fantasy Nonfiction Biography & Memoir Teens & Young Adult Children's

- News & Features Bestsellers Book Lists Profiles Perspectives Awards Seen & Heard Book to Screen Kirkus TV videos In the News

- Kirkus Prize Winners & Finalists About the Kirkus Prize Kirkus Prize Judges

- Magazine Current Issue All Issues Manage My Subscription Subscribe

- Writers’ Center Hire a Professional Book Editor Get Your Book Reviewed Advertise Your Book Launch a Pro Connect Author Page Learn About The Book Industry

- More Kirkus Diversity Collections Kirkus Pro Connect My Account/Login

- About Kirkus History Our Team Contest FAQ Press Center Info For Publishers

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Reprints, Permission & Excerpting Policy

© Copyright 2024 Kirkus Media LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Popular in this Genre

Hey there, book lover.

We’re glad you found a book that interests you!

Please select an existing bookshelf

Create a new bookshelf.

We can’t wait for you to join Kirkus!

Please sign up to continue.

It’s free and takes less than 10 seconds!

Already have an account? Log in.

Trouble signing in? Retrieve credentials.

Almost there!

- Industry Professional

Welcome Back!

Sign in using your Kirkus account

Contact us: 1-800-316-9361 or email [email protected].

Don’t fret. We’ll find you.

Magazine Subscribers ( How to Find Your Reader Number )

If You’ve Purchased Author Services

Don’t have an account yet? Sign Up.

Accessibility Tools

- Invert colors

- Dark contrast

- Light contrast

- Low saturation

- High saturation

- Highlight links

- Highlight headings

- Screen reader

- Keyword -->

The Yield by Tara June Winch

- decrease font size Text increase font size

The Yield by Tara June Winch

Hamish Hamilton, $32.99 pb, 352 pp, 9780143785750

W iradjuri writer Tara June Winch is not afraid to play with the form and shape of fiction. Her dazzling début, Swallow the Air (2006), is a short novel in vignettes that moves quickly through striking images and poetic prose. Her second book, After the Carnage (2017), a wide-ranging short story collection, is set in multiple countries. Winch’s new novel, The Yield , is partly written in reclaimed Wiradjuri dictionary entries.

Three different voices narrate The Yield in bite-sized chapters: dictionary maker and elder Albert Gondiwindi, his granddaughter August, and nineteenth-century missionary Reverend Greenleaf. It takes some time to get used to this structure, but ultimately it is rewarding. The different perspectives introduce us to life in the place where the Gondiwindi family live: Prosperous House, in the fictional town of Massacre Plains. Abbreviating, the Aboriginal characters call it ‘Massacre’. This contraction is pointed: Winch reminds us we are in a site of settler–invader violence, one without a treaty. Admirers of Kim Scott’s Taboo and Melissa Lucashenko’s Too Much Lip will enjoy Winch’s Aboriginal realism.

August, the main character in the present-day narrative, is in her early twenties but world-weary. She comes back to Country for Pop Albert’s funeral after spending a decade abroad, running away from a past. August never had a childhood, never had a break. Often said to be depressed, she sees her country in less than flattering terms: a ‘sparse, foreboding landscape’, dripping with ‘visual heat’, where everything is ‘browner, bone-drier’.

In contemporary Aboriginal fiction, a common theme is ‘returning’ – returning to Country, family, language, and culture, all of them intertwined. August’s family, on her return, is riven by an upcoming mining decision. There is a hole left by a sister’s disappearance: a mystery decades-old. August also comes back to an old love interest, Eddie; this ‘returning novel’ offers something new in its Wiradjuri framing, a language in a state of resurgence, with a growing number of speakers. The New Wiradjuri Dictionary by Dr Uncle Stan Grant Sr and Dr John Rudder informs the language in The Yield.

It was an effective move on Winch’s part to resist writing August in the first person. Through the third-person narration we are also able to get inside the heads of other characters, to see the place from multiple angles. It is a novel that rewards readerly patience; it takes a while to realise what’s at stake. Slowly, we become entangled in the characters’ lives. With August’s parents out of action – incarcerated on drug charges (‘never mean and bad parents, just distracted, too young and too silly’) – Winch deftly unpacks relationships between grandparents and grandchildren, aunties and nieces, and cousins.

As the tin-mining company claims a stake in Massacre Plains, as pipes and fences are secured, white environmental activists descend, calling into question black and green relations, the future of the environment and native title. August imagines herself free-falling to the bottom of a tin pit. The Yield is an anti-mining novel for the present day in the wake of the approval of the Adani coal mine in central Queensland.

Rich with cultural knowledge, Albert’s story-in-dictionary form shows us not only how to read Wiradjuri but also how to feel and speak and taste it; it decolonises the throat and tongue. Winch asks timely questions: What does contemporary use of language look like? What can it offer us in our lives? What can it do for the overall health of our country?

The Yield is about regaining more than language. There are odes to Bruce Pascoe’s Dark Emu , with the pointed inclusions of bush food, bread, and fishing technology. There are only a few places where Winch’s delivery is too didactic, as when Nana tells August, the author speaking directly down the barrel to the reader, ‘we aren’t victims in this story anymore – don’t you see that?’

The Yield will appeal to many because of the way it unpacks complex themes in an accessible way. Australian rural novels are often humourless sketches with characters more like caricatures, grimly serious or full of despair. Refreshingly, the characters in The Yield are capable of communion, humour, and dignity despite tragedy, sexual violence, and substance abuse. In this deft novel of slow-moving water, they are borne by love, not pity.

Ellen van Neerven

- Tara June Winch

- Hamish Hamilton

- Indigenous Writing

- Australian Fiction

- Miles Franklin Literary Award Winner

- PM's Literary Award Winner

Ellen van Neerven (born in Meanjin (Brisbane) in 1990) is an award-winning writer and editor of Mununjali Yugambeh (South East Queensland) and Dutch heritage. Ellen’s first book, Heat and Light , was the recipient of the David Unaipon Award, the Dobbie Literary Award and the NSW Premier’s Literary Awards Indigenous Writers Prize. Ellen’s second book, a collection of poetry, Comfort Food , was shortlisted for the NSW Premier’s Literary Awards Kenneth Slessor Prize and highly commended for the 2016 Wesley Michel Wright Prize. Throat is Ellen’s second poetry collection, a May 2020 release.

(Photograph by Anna Jacobson)

From the New Issue

The future of ABR Arts

Mural by Stephen Downes

Noble Fragments: The maverick who broke up the world’s greatest book by Michael Visontay

Why Surrealism Matters by Mark Polizzotti

You may also like.

The Black Russian by Lenny Bartulin

Going Down Swinging, No. 28 by Lisa Greenaway and Klare Lanson

The Fifth Season by Philip Salom

Smokehouse by Melissa Manning

Comments (4).

- A brilliantly written novel. So many issues cleverly intertwined. A good acknowledgment of our First Nations People. Posted by June Worthington 05 May 2021

- Truth telling in real time! Posted by Pauline Callan 15 March 2021

- An extraordinary, valuable book, so readable. Our Wiradjuri nation, language, culture are a rich, priceless gift for the region where I live. Tara June Winch and her characters articulate for the reader so poignantly complexities of not only my local history in the Riverina but Australia. I am drawn into deeper reflection and appreciation of all that needs to be recognised and done for true justice. Posted by Joan Saboisky 18 January 2021

- I feel ‘privileged and humbled’ to read this book. Strange words perhaps, but I appreciate so much the intimacy and truths behind the three narratives. The power of the pen and word. May it lead to justice, equality and healing for the First Nations People. Posted by Patricia Jessen 10 September 2020

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments . We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions .

- Forgot username?

- Forgot password?

WRITER AND RESEARCHER

Review of 'The Yield' by Tara June Winch

In her Barry Andrews address at the recent Association for the Study of Australian Literature conference, Wiradjuri writer and scholar Professor Anita Heiss exhorted academics who teach and write about Aboriginal literature to commit to raising awareness about Aboriginal literacy and languages in their work. She also suggested donating to or fundraising for the Indigenous Literacy Foundation which, among other things, produces and publishes books by Indigenous people for Indigenous people.

Professor Anita Heiss’s call to action.

I started reading Aboriginal literature at university. My education expanded exponentially when I started reading and reviewing for the Australian Women Writers Challenge (proving that you don’t have to go to uni to read Aboriginal peoples’ writing!). So although of late I have wondered whether it is apposite to apply the tools of literary criticism, which have a European lineage, to Aboriginal texts (particularly given the colonial baggage of those tools), I still think it’s really important for non-Aboriginal readers to engage with Aboriginal literature to educate ourselves about Australian history, Aboriginal culture and Aboriginal languages.

Although it has been postponed this year due to Covid, this past week was due to be NAIDOC week. During this week, Lisa of ANZLitLovers encourages litbloggers to read and engage with Indigenous literature across the world . As this is an online initiative, it didn’t have to be cancelled! Over the past few years I have been too overworked and exhausted to do any reviews, but due to my Covid-19 reboot I’ve read and thought about Tara June Winch’s The Yield (which we also did in bookclub at Avid Reader ).

The Yield , Winch’s third work and first novel, is a book about words, particularly Ngurambang , ‘the word for country in the old language, the first language’ (1). The book begins and ends with this word, signalling the continuation of country because, as Albert Gondiwindi, a collector of Wiradjuri words, signals, he’s writing about ‘deep time. This is a big, big story. The big stuff goes forever, time ropes and loops and is never straight, that the real story of time’ (2).

The story is made up of three narratives: Albert Gondiwindi’s first person narrative and dictionary entries in Wiradjuri and English; the third-person story of August Gondiwindi, Albert’s granddaughter, who returns to Australia from England following Albert’s death and who is haunted by the loss of her sister; and a long letter written by Reverend Ferndinand Greenleaf in 1915, describing his attempts at creating a missionary for the Gondiwindi people. These three stories knit together at the book’s close, in which the action speeds up dramatically in a protest against a tin mine to be opened on Ngurambang .

A major theme in the book is the body, with which Ngurambang is bound. As Albert writes, ‘If you say [ Ngurambang ] right it hits the back of your mouth and you should taste blood in your words’ (1). He also observes that his country ‘had a plan for me, already mapped in my veins since before I was born’ (1). The blood is in the word, which is in the veins, in the body, in the land.

Thus I read August’s under-nourishment as synchronous with, and linked to, the gradual drying of the Murrumby River since colonisation. As Augustine writes in his entry for ‘river – bila ’:

Now you know where the word billabong comes from. From us. Everything comes back to the bila – all life, and with it all time. Our songlines originate there, our lives fed from there and it’s where our spirits dwell in the end. Even the Reverend was drawn to the river, there he recited Isiah 44:3, For I will pour water on the thirsty land, and streams on the dry ground; I will pour my Spirit upon your offspring, an my blessing on your descendants. Can’t imagine how it hurts not to see that water come anymore. (106)

Language is bound up with bodies, because language comes from country, and country nourishes the body. When the novel’s sequence of events are resolved, August is returned to her body. She listens to a tape made by Albert of the old language. It is ‘his recital, his private sermon, going through a list of words, trying as he did to work out or remember how they were pronounced’ (306). Hearing this language, ‘the smells, tastes and burdens left August. She ate again, too, she wasn’t ngarran anymore. English changed their tongues, the formation of their minds, August thought – she’d drifted in and out of herself all that time. The language was the poem she had looked for, communicating what English failed to say’ (306). This sustenance also comes from the sound of the words, as Aboriginal culture is an oral culture, although as Penny van Toorn has illustrated, Aboriginal people were very quick to pick up writing once that technology was available to them.

August and her cousin Joey print out the pages of the book for the local kids, and write in the Foreword: Maybe you are looking for a statue, or a bench by the banks of the Murrumby to honour the people who have lived by the river. Better, there is water returning, nudging what was dead. Better the burral-gang congregate here often. Better these words and better we are still here and that we speak them . (310)

I thought this was interesting in the context of the recent debates about statues. There are different ways to commemorate history, not just through cast iron figures. Cultures with oral histories, where memory is passed down by story, have different ways of remembering & commemorating to Westerners, who seem to like monuments (as for me, I am indifferent: the span of history is so long that humans are but a speck, and a statue memorialising a speck doesn’t mean much to me). This passage shows that Wiradjuri people have resisted colonisation and that they are still sustained by their country, by memory, and by language.

As was pointed out in our bookclub meeting, The Yield is a generous book. Many of the missionaries in Australia sure didn’t abide by their Christian principles, as Claire G. Coleman details in Terra Nullius , and many of the girls’ and boys’ homes in which Aboriginal children were institutionalised during the Stolen Generations (and, arguably, still are), ‘were much harsher in comparison to those depicted’ in the novel (Winch, 340). Winch shows a missionary who was influenced by the Gondiwindi people and wrote down their language. This doesn’t mean he was an entirely good person, as an exchange between August and her aunt Missy reveals:

‘He was kind, you think?’ [August asks]. ‘No. He was bad in a long pattern of bad. I reckon he just thought he was doing right.’ ‘He regretted it.’ ‘Yeah, but only when it happened to him, aye.’ (250).

So I think it’s interesting that Winch includes the lines from Isiah in the definition of billabong . Perhaps she’s trying to use Christianity, which with white Australians might be familiar, to explain a concept from Aboriginal culture. It’s generous, because Aboriginal people shouldn’t have to do this work – there’s hundreds of books out there that folk can pick up and read to learn about Aboriginal culture.

At the same time, even if Winch doesn’t go into great details about massacres and rapes (although these are present in the book), she does canvas the casual racism that Aboriginal people experience. While standing in the fish n’ chips shop, August looks at a man’s tattoo of the Southern Cross, inked onto his shoulder.

‘You like that?’ he asked her, pointing to it, without waiting for an answer. ‘That’s the Southern Cross, lady. That means you don’t belong here.’ She stood there dumbfounded, blank-faced. After a moment she wondered who he thought she was, or who exactly he thought he was. (237).

A subtle way of revealing ignorance.

My favourite part of this book is the dictionary: I loved the Wiradjuri words and the stories used to explain them, such as ‘ flower, a kind of flower – babin, narranarrandyiran The banksia flower is my favourite, not just because it’s large and proud looking like the hibiscus, but because it reminds me of something bigger. See, the banksia is a tough-looking flower but it still protects itself with sharp, jagged leaves, study wood and roots. Its nectar feeds the bees, the birds and us people’ (206). A plant is always bigger than a human, because without sugar and oxygen from plants, humans can’t survive, so I liked this interpretation.

The writing in the dictionary section is much more alive and vibrant than that of the Reverend’s letters, which came across as flat and two-dimensional. Perhaps that was the point, but I skimmed a lot of those letters – he didn’t seem real to me.

A few other thoughts: there were bits that made me laugh. When August asks her Aunt Missy, ‘You think you’ll go to heaven, Aunty?’, Missy replies, ‘Nah! I’ll be back as a tree or something that doesn’t move. I just want to chill out and not have to go hunting for food, you know?’ (249). I agree: trees are something to aspire to. I also wondered if this book was a shout out to Alexis Wright’s Carpentaria , with the name of the towns Prosperous and Massacre Plains echoing Wright’s Desperance, and the gathering of activists at the end of The Yield also mirroring the blowing up of the mine in Carpentaria . I dunno, but I liked the use of allegory.

When Black Lives Matter exploded in America, and people marched against inaction over Deaths in Custody in Australia (437 deaths since 1991 and not a single conviction! It’s staggering), readers rushed to bookshops to buy books by Aboriginal writers. I find that really heartening, but there also needs to be concrete action - for example we should, as Anita Heiss stresses, we should amplify Aboriginal peoples’ voices . So don’t just read this (rather hamfisted) review - go out and buy the book.

Review: The Yield by Tara June Winch

I didn’t plan to read the nonfiction book Dark Emu shortly before reading the novel The Yield by Tara June Winch.

But I couldn’t think of a better pairing. While Dark Emu deconstructs colonial myths about Australian Aboriginal civilizations, The Yield illustrates how these myths were used to justify tearing apart families and cultures.

In the novel, August Gondiwindi reluctantly returns home for the funeral of her grandfather Albert “Poppy” Gondiwindi, who had been creating a dictionary of his people’s language, a dictionary suddenly gone missing. As August revisits her past relationships and painful memories she also begins searching for this manuscript.

Meanwhile, a mining company is days away from forcing her family from their ancestral home in western New South Wales. Environmentalists are not about to go down without a fight, a fight that August initially believes is not her fight.

August had always thought important events happened in every other country expect for Australia. That the tremors of their small lives meant nothing. But at that moment … she felt as if she’d awoken from a stony sleep to find herself standing on the edge of something larger than she’d ever been able to see before.

What I loved about this novel is the central role language plays within it. In alternating chapters, the reader gets a firsthand look at a dictionary in the making, one word at a time, narrated by Poppy. This device could have pulled the reader out of the story; instead, the words and their descriptions send the reader on a hundred different brief journeys, while propelling the narrative forward. For example, the phrase giya-rra-ya-rra (afraid to speak) leads to a painful story about August’s grandfather and his wife when they tried to take a class of college students to the local swimming pool and the racism they met along the way. And garrandarang (book) sheds light on where the elusive manuscript had been taken.

The Yield tells the story of a people and a culture torn from the land and one another. But it’s also a story about remembering and resistance. Ultimately, August must look backwards before she can move forwards and, in doing so, realize her passion and purpose in life.

Along the way, you might pick up a few words from the Wiradjuri language. Winch notes that before Europeans arrived there were 250 distinct Australian languages, subdivided into 600 dialects.

Wiradjuri is one of these reclaimed and preserved languages, a language that is with us today (even if we don’t fully realize it). As Poppy writes about the word bila (river): Now you know where the word billabong comes from.

The Yield Tara June Winch HarperVIA

John is co-author, with Midge Raymond, of the Tasmanian mystery Devils Island . He is also author of the novels The Tourist Trail and Where Oceans Hide Their Dead . Co-founder of Ashland Creek Press and editor of Writing for Animals (also now a writing program ).

Username or Email Address

Remember Me

Book Reviews by Dr.Mani

Best Book Reviews You've Ever Read!

Book Review : THE YIELD by Tara June Winch

“Ngu-ram-bang. If you say it right it hits the back of your mouth and you should taste blood in your words. “

This isn’t an easy or light-hearted novel to read. The writing is brilliant, but the subject matter weighty.

After reading an interview with Tara June Winch in ‘ The Guardian ‘, I picked up her latest book – The Yield .

Right from the first sentence, it grips and doesn’t let go.

‘The Yield’ is a story about the collective identity of an aboriginal Native Australian tribe with a rich, long heritage. A tale narrated through the medium of a dictionary which lists the words of a forgotten tongue – and that’s woven into the storytelling in a memorable, admirable way.

August Gondiwindi returns to bury her grandpa. And through her account we learn about customs and language of an ancient tribe. What ancestors went through while establishing their tribe. How elements and entrenched power centers interfered with the process.

Parable and fantasy mix into the telling of how early settlers to Prosperous built a community along the fictional Murrumby River .

A settlement that was later on usurped by immigrants, leaving the original landowners bereft. In flashback we learn about the mysterious disappearance of her sister Jedda and other disturbing or memorable incidents from a faraway childhood that, in a roundabout way, have a bearing on what she will do today.

After almost a decade in England, she is informed about her grandfather’s demise – and decides to come and say goodbye.

For August, it’s a bittersweet homecoming.

“August wandered the property, pausing only to listen more closely to the familiar soundtrack playing, encasing the world, in cicada friction and bird whip… Here, she remembered, summer wasn’t a season, it was an Eternity.”

She integrates back into a community she’d abandoned long ago.

Reconnects with her Nana. Meets aunts and cousins. Runs into her childhood romantic flame.

And all the while, she watches the threatened disaster of a mining project loom larger as a deadline approaches. Joins a futile protest to hold back the relentless march of ‘progress’, ‘prosperity’ and ‘jobs’.

The key to salvaging the ancestral Wiradjuri land lies in a rumored book her grandpa Poppy had been writing – but which she cannot find.

A book which is actually a dictionary of the ancient language, the words of which are the pillars holding up this tale.

For a book about language, Tara June Winch’s ‘ The Yield ‘ is written oh-so-beautifully.

Dotted throughout the book are gems like this:

“…the sliver of silver moon bent through the empty glass.”

Words are chosen, and sentences crafted, with such care and attention that even the most mundane scenes take on a sense of the sublime.

But though it’s also about words, language and culture, this is essentially a book about identity – and how it’s linked to your land and your people.

And we watch as August Gondiwindi reclaims her place, rediscovers herself, redeems her heritage.

‘ The Yield ‘ in English is the reaping, what man takes from the land. In the Wiradjuri language, ‘ The Yield ‘ is what you give to, the space between things.

‘ The Yield ‘ is a fantastic read. It is a great way to appreciate and understand the impact our pasts have on the present – and our collective futures.

‘ The Yield ‘ will leave you feeling stirred and shaken – in a good way.

EXCLUSIVE OFFER!

- Bookings & Fees

- Endorsements

- The 50 Authors Who Shaped Me

- The 50-50 Project

- Historical Fiction

- Fiction for Adults

- Creative Non-Fiction

- Fiction for Children

- Picture Books

- Online Workshops

- From Ancient Myths to Modern Storytellers Retreat

- Creative Writing in the Cotswolds

- Writing Journal

- What Katie Read

- Author Interviews

BOOK REVIEW: The Yield by Tara June Winch

The Blurb (from Goodreads):

Knowing that he will soon die, Albert ‘Poppy’ Gondiwindi takes pen to paper. His life has been spent on the banks of the Murrumby River at Prosperous House, on Massacre Plains. Albert is determined to pass on the language of his people and everything that was ever remembered. He finds the words on the wind.

August Gondiwindi has been living on the other side of the world for ten years when she learns of her grandfather’s death. She returns home for his burial, wracked with grief and burdened with all she tried to leave behind. Her homecoming is bittersweet as she confronts the love of her kin and news that Prosperous is to be repossessed by a mining company. Determined to make amends she endeavours to save their land – a quest that leads her to the voice of her grandfather and into the past, the stories of her people, the secrets of the river.

Profoundly moving and exquisitely written, Tara June Winch’s The Yield is the story of a people and a culture dispossessed. But it is as much a celebration of what was and what endures, and a powerful reclaiming of Indigenous language, storytelling and identity.

My Thoughts:

Tara June Winch is a Wiradjuri author whose first novel, Swallow the Air, was published in 2006, when she was only 23. I met her at a literary festival that year, and remember being captivated by her intensity and passion, as well as the beauty of her words. Two years later, she won a mentorship with Nobel Prize winner Wole Soyinka as part of the prestigious Rolex Mentor and Protégé Arts Initiative. The Yield is her third novel, and entwines three very different voices.

The first is that of an old man, Albert ‘Poppy’ Gondiwindi, who knows he is soon to die. He decides to record a dictionary of Wiradjuri words to save them from extinction: ‘The yield in English is the reaping, the things that man can take from the land. In the language of the Wiradjuri yield is the things you give to, the movement, the space between things: baayanha .’

Poppy Gondiwindi’s life has been spent on his traditional lands, in what was an old Lutheran mission on the banks of the Murrumby River, on Massacre Plains. The second voice is that of the pastor, Reverend Ferdinand Greenleaf, who founded the mission at the turn of the 19 th century.

These two accounts are very different, and show that Tara June Winch is a skilled ventriloquist.

The third voice is that of a young woman, August Gondiwindi, who has been living overses for many years. Coming home for her grandfather’s funeral, she has to face the ghosts of her past. Discovering that her family’s home is to be repossessed by a mining company, she searches for her grandfather’s dictionary of Wiradjuri language in the hope she can prove a land title claim and so save her country. Along the way, August discovers some truths about herself and her past that help her to travel towards healing and forgiveness.

‘I was born on Ngurambang – can you hear it? – Ngu–ram–bang . If you say it right it hits the back of your mouth and you should taste blood in your words. Every person around should learn the word for country in the old language, the first language – because that is the way to all time, to time travel! You can go all the way back.’

Beautiful and powerful!

You might also like to read my review of Melmoth by Sarah Perry:

https://kateforsyth.com.au/what-katie-read/book-review-melmoth-by-sarah-perry

You May Also Like

LIZZIE SIDDAL: Her Life & legacy

BEAUTY IN THORNS

SPOTLIGHT: The PreRaphaelite Sisterhood

Join my vip club.

By subscribing you agree to receive my VIP offers and Newsletters. You may unsubscribe at any time

The Yield by Tara June Winch

“I was born on Ngurambang — can you hear it? — Ngu-ram-bang. If you say it right it hits the back of your mouth and you should taste blood in your words. Every person around should learn the word for country in the old language, the first language — because that is the way to all time, to time travel! You can go all the way back.”

Winner of the Miles Franklin Literary Award 2020, Book of the Year, People's Choice, Christina Stead Prize for Fiction at NSW Premier's Literary Award, and shortlisted for the VPLA and the Stella Prize, The Yield (2019) is the third book from Wiradjuri author, Tara June Winch, and one well worth spending some time with.

I’ve previously found myself with unmet expectations when picking books similarly heaped with praise and awards, but that was not the case with The Yield . Told through three different narrators, written in three different styles, Winch wields together a story that spreads its wings across decades and cultures.

Albert ‘Poppy’ Gondiwindi is dying. Knowing this, he begins to write a dictionary of sorts, the words of his people and ancestors, and in doing so, he tells us his own story.

August Gondiwini, Abert’s granddaughter, has been living in London for a decade. Running from her past and ancestors, she is called back to her home in Massacre Plains when she learns of her grandfather’s death.

The third narrator in the book is Reverand Ferdinand Greenleaf, whose experiences we learn about through a series of letters back to England. He details his early settlement in Australia and the challenges of setting up a Mission in 1880. Winch introduces us to the past, present and future of Massacre Plains and the Gondiwindi mob with each narrator.

On returning home, August is confronted by the past she has desperately been trying to escape: her lost sister, her ruptured family, and her fractured identity.

“Since she was a girl, the ache had scratched further inside her, for something complete to rest at her tongue, her throat. The feeling that nothing was ever properly said, that she'd existed in a foreign land of herself.”

Most of the novel centres around August and the impact of intergenerational trauma. Repeatedly we are made aware of how thin August is, her lack of appetite and her reluctance to acknowledge what she is doing to herself. On first returning home, August’s sense of displacement is keenly felt, but as the novel progresses, she begins to find her feet as she is taken under the wings of her aunties and relatives. Her belonging, though, is woven with pain:

“She closed her eyes, a dam had broken, broken their little hearts, hearts born as fragile as clay. With her hands flat on the dry dirt and her eyes blinded by tears, she felt as if she were back home, back on the land she belonged to. At the same time, she thought that this was the saddest place on earth.”

August learns that the land her grandparent’s home resides on has been claimed under a 99-year land lease (something Winch doesn’t explain but is worth researching) and is to be demolished for a tin mine to be developed. As her grandmother prepares to pack and leave, August also learns Albert was writing a book, a dictionary of their language, and she sets out to find out what has happened to it. In the process, she begins to uncover more about the land, the past and her mob, feeling the threads of connection joining her back to her homeland.

As the mining contractors move closer, August is in a race against time to find Albert’s words and prove the Gondiwindi’s claim to the land as a place of cultural significance and Native Title rights.

Albert’s part of the story is told through his dictionary, sharing the language of the Wiradjuri people, their meanings both in terms of translation, cultural and personal. Using language in this way is a unique lens: it shows the power of words and how a shared dialect unites communities (something Winch also touches on in her 2006 debut novel Swallow the Air ). In her author’s note, Winch draws our attention to the poignancy of using language in her novel in this way:

“Cultural knowledge, community history, customs, modes of thinking and belonging to the land are carried through languages. In the last two hundred years, Australia has suffered the largest and most rapid loss of languages known to history. Today, despite efforts of revitalisation, Australia’s languages are some of the most endangered in the world.”

Albert’s voice is strong, and reading through his dictionary in this manner felt symbolic to me, an elder sharing lessons and the value of staying connected to the things that draw you back to family and place. It is also a reminder of how much has already been lost in Australia and the importance of seeking out an education for the lands we call home beyond media highlights.

Reverend Greenleaf’s letters, for those unfamiliar with Australia’s colonial history, provide a raw insight, but Winch also keeps this accessible. The use of a white man to tell this part of the story perhaps creates a layer of removal for the author while continuing to invite the newer reader into Australia’s terrible past. While it would be easy to adopt Greenleaf as a standout, that all white men were ‘not bad’, Winch also nods to the problems of white saviours. On finding his letters, August and her Aunt Missy discuss the early settlement of the mission with Reverand Greenleaf at its helm:

“‘He was kind, you think?’ ‘No. He was bad in a long pattern of bad. I reckon he just thought he was doing right.’ ‘He regretted it.’ ‘Yeah, but only when it happened to him too, aye.’”

Winch attempts to achieve a lot with this book. It gears up rapidly in the final quarter, with many threads of the story tied up quickly and neatly, despite how much energy is given to them in the early part of the book. Albert’s voice is the strongest throughout, and perhaps that is how the story is supposed to be read; a voice of an elder, long denied his place and language, striking through the most.

The Yield powerfully shows us the effects of intergenerational trauma, dispossession, and abuse. It shows us the empowerment of language and leaves us with a strong idea of a future Australia, one imbued with hope and healing.

Elaine Mead is a freelance writer and book reviewer, currently residing in Hobart, Tasmania. She is passionate about the ways we can use literature to learn from our experiences to become more authentic versions of ourselves and obsessed with showing you photos of her Dachshund puppy. You can find her online under @wordswithelaine .

Elaine is a freelance writer and book reviewer, currently residing in nipaluna (Hobart), Tasmania. She is passionate about the ways we can use literature to learn from our experiences to become more authentic versions of ourselves and obsessed with showing you photos of her Dachshund puppy. You can find her online under www.wordswithelaine.com.

Poetry Collections We Can’t Wait to Read in 2021

Queer classics for every bookshelf (and a few modern ones too).

Winch, an award-winning Aboriginal Australian writer who is now based in France, uses this dictionary of recovered indigenous words to transmit the deeper story of Gondiwindi family history. We read it—and the novel as a whole—with both sorrow and hope.

In Tara June Winch’s engaging third book, The Yield , a young woman named August Gondiwindi flies back to Australia, rents a car and drives seven hours inland to the aptly named town of Massacre Plains. This is the small town where August grew up in the care of her grandparents. It’s a place “where the sun slap[s] the earth with an open palm.” It’s the place she fled as a teenager after the traumatic disappearance of her older sister and protector. She is returning after many years for the funeral of her grandfather, Albert “Poppy” Gondiwindi, a revered Wiradjuri (indigenous Australian) elder. She soon discovers that her grandmother and family members are being evicted from their lands because an extraction company has acquired the mineral rights and plans to excavate a vast open-pit tin mine.

Even with a slightly pat ending, this thread of Winch’s narrative is irresistible, as she offers the reader both a tactile and spiritual feel for the forbidding landscape. Her portrayal of August’s rediscovery of herself and her ties to her home is moving. She presents the legacy of oppression and strife among local indigenous people and European settlers with great nuance.

But it’s when this initial thread intertwines with two other storylines that the novel fully realizes itself. One of these narratives is a long letter, a testimony of sorts, from an early 19th-century missionary who finds his calling among the oppressed Wiradjuri. In contrast to church and government powers, he comes to oppose the policy of tearing children from their families in order to “civilize” them. He realizes that the supposed “stupidity” of the indigenous people is actually a profound understanding of their environment. He worries constantly that his ministrations are not helpful, and he discovers that his advocacy makes him a hated outsider.

The other and most innovative thread involves excerpts from the dictionary of Wiradjuri words that Poppy begins compiling near the end of his life. Stripping a people of their language is a standard method for snuffing out indigenous cultures. Poppy’s effort is an act of resistance and affirmation. But the dictionary appears to be lost, and one of August’s quests is to find it.

Trending Reviews

Valiant Women

Lena s. andrews.

- By Deborah Hopkinson

Notes from an Island

Orlagh cassidy, tove jansson.

- By Tami Orendain

Pavlo Gets the Grumps

Natalia shaloshvili.

- By Linda M. Castellitto

Get the Book

Stay on top of new releases: Sign up for our newsletter to receive reading recommendations in your favorite genres.

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Aug 30, 2020 · yield, bend the feet, tread, as in walking, also long, tall – baayanha Yield itself is a funny word – yield in English is the reaping, the things that man can take from the land, the thing he’s waited for and gets to claim. A wheat yield. In my language it’s the things you give to, the movement, the space between things.

Jul 2, 2019 · Some are more spiritual in nature – exploring the different world views and approaches of captured in the Wiradjuri on contrast to the same words in English – and how these difference concepts capture how relationships developed, for example the title of the book. yield, bend the feet, tread, as in walking, also long, tall—baayanha Yield ...

Jun 2, 2020 · A young woman’s experience as a nurse in Vietnam casts a deep shadow over her life. When we learn that the farewell party in the opening scene is for Frances “Frankie” McGrath’s older brother—“a golden boy, a wild child who could make the hardest heart soften”—who is leaving to serve in Vietnam in 1966, we feel pretty certain that poor Finley McGrath is marked for death.

The Yield is an anti-mining novel for the present day in the wake of the approval of the Adani coal mine in central Queensland. Tara June Winch (photograph via Wikimedia Commons) W inch is highly skilled at creating portraits and at moving us forward into space.

Jul 12, 2020 · The Yield, Winch’s third work and first novel, is a book about words, particularly Ngurambang, ‘the word for country in the old language, the first language’ (1). The book begins and ends with this word, signalling the continuation of country because, as Albert Gondiwindi, a collector of Wiradjuri words, signals, he’s writing about ...

Feb 2, 2021 · I didn’t plan to read the nonfiction book Dark Emu shortly before reading the novel The Yield by Tara June Winch.. But I couldn’t think of a better pairing. While Dark Emu deconstructs colonial myths about Australian Aboriginal civilizations, The Yield illustrates how these myths were used to justify tearing apart families and cultures.

Nov 12, 2021 · A book which is actually a dictionary of the ancient language, the words of which are the pillars holding up this tale. For a book about language, Tara June Winch’s ‘The Yield‘ is written oh-so-beautifully. Dotted throughout the book are gems like this: “…the sliver of silver moon bent through the empty glass.”

The Yield is her third novel, and entwines three very different voices. The first is that of an old man, Albert ‘Poppy’ Gondiwindi, who knows he is soon to die. He decides to record a dictionary of Wiradjuri words to save them from extinction: ‘The yield in English is the reaping, the things that man can take from the land.

Mar 16, 2021 · Winner of the Miles Franklin Literary Award 2020, Book of the Year, People's Choice, Christina Stead Prize for Fiction at NSW Premier's Literary Award, and shortlisted for the VPLA and the Stella Prize, The Yield (2019) is the third book from Wiradjuri author, Tara June Winch, and one well worth spending some time with.

In Tara June Winch’s engaging third book, The Yield, a young woman named August Gondiwindi flies back to Australia, rents a car and drives seven hours inland to the aptly named town of Massacre Plains. This is the small town where August grew up in the care of her grandparents.