15 Cultural Landscape Examples (Human Geography)

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

Learn about our Editorial Process

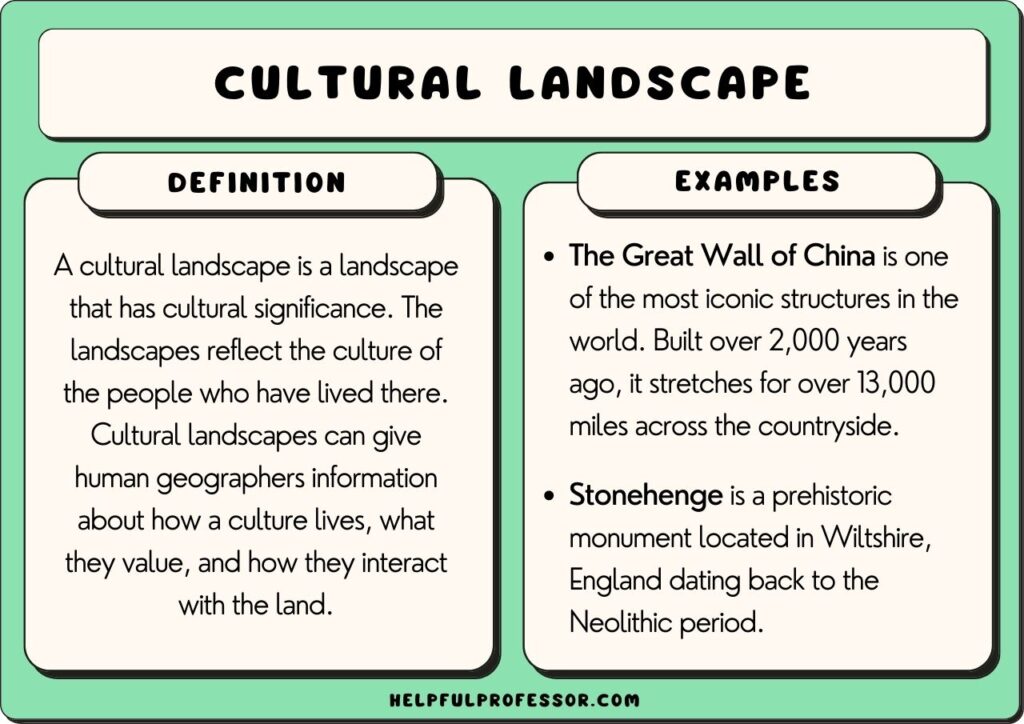

A cultural landscape is a landscape that has cultural significance. The landscapes reflect the culture of the people who have lived there.

Cultural landscapes can give human geographers information about how a culture lives, what they value, and how they interact with the land.

Examples of cultural landscapes include golf courses, urban neighborhoods, agricultural fields, relics, and heritage sites.

Types of Cultural Landscapes

In 1992, UNESCO created three categories of cultural landscapes. These were:

- Clearly defined landscape: These are landscapes conspicuously crafted by humans and that continue to be maintained as cultural sites. The Taj Mahal and urban gardens are examples of clearly defined landscapes.

- Organically evolved landscapes: Organically evolved landscapes have evidence of human interaction with the land, but it has changed and developed over time. Interaction between the elements and the land is evident. An example is a relic wall such as Hadrian’s Wall, or even ancient farmland that has been, and still is, in use for thousands of years.

- Associative cultural landscapes: These landscapes may not have clear evidence of human interaction, but nonetheless of cultural importance. For example, Uluru in Australia is a giant rock of importance to Aboriginal Australians because they practice ceremonies there. There isn’t evidence of interaction with the land, and yet it is highly significant to Aboriginal people.

Cultural Landscape Examples

1. uluru (australia).

Type: Associative cultural landscape

Situated in the heart of Australia’s Northern Territory, Uluru (formerly known as Ayers Rock) is one of the country’s most iconic landmarks. The massive sandstone monolith has long been revered by the Aboriginal people of the region, who hold it to be a sacred site.

Uluru is believed to be the home of the spirits of their ancestors, and it features prominently in many of their stories and ceremonies.

In recent years, Uluru has also become a popular tourist destination, with visitors coming from all over the world to admire its majestic beauty.

While it is undoubtedly an impressive natural wonder, Uluru also holds great cultural significance for the Aboriginal people of Australia.

Related Article: Cultural Pluralism Vs Multiculturalism

2. The Great Wall of China (China)

Type: Organically evolved landscape

The Great Wall of China is one of the most iconic structures in the world. Built over 2,000 years ago, it stretches for over 13,000 miles across the countryside.

For centuries, it served as a barrier to protect China from invaders. Today, it is a popular tourist destination and a symbol of China’s rich history and culture.

The Great Wall is also significant for its architectural ingenuity. Its unique design – featuring watchtowers, battlemented, walls and staircases – is a testament to the skill of ancient Chinese builders.

In 2007, the Great Wall was designated as a UNESCO World Heritage site. This recognition not only highlights its cultural importance but also underscores the need to protect this unique structure stretching across the Chinese landscape for future generations.

3. Machu Picchu (Peru)

Machu Picchu is one of the most famous archaeological sites in the world, and it has a long history of cultural significance. The site was built by the Inca civilization in the 15th century, and it served as a royal estate for the Inca emperor Pachacuti.

After the fall of the Inca Empire, Machu Picchu was abandoned and forgotten until it was rediscovered by Hiram Bingham in 1911.

Today, Machu Picchu is a major tourist destination, and it is also an important symbol of Inca culture. The site has been designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and it continues to be a place of pilgrimage for many Andean people.

4. The Grand Canyon (United States of America)

The Grand Canyon is one of the most iconic natural landmarks in the United States. Carved over millions of years by the Colorado River, the canyon is a stunning display of geologic history.

It is also an important cultural site for many Native American tribes.

The canyon is home to a number of sacred places, including burial grounds and sites of religious ceremonies. For centuries, the tribes that have lived in or near the canyon have held it in high esteem, regarding it as a place of great power and mystery.

In recent years, the Grand Canyon has also become a popular tourist destination. Tourists can hike, camp, raft and otherwise explore the canyon’s vast expanse.

5. Stonehenge (Wiltshire, England)

Stonehenge is a prehistoric monument located in Wiltshire, England. Dating back to the Neolithic period, it is composed of rings of standing stones, each weighing several tons.

The purpose of Stonehenge is unclear, but it is believed to have been used for ceremonial or religious purposes.

Today, Stonehenge is a popular tourist destination and a symbol of British heritage. It has been designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site and is considered one of the Wonders of the World.

Though its exact origins remain shrouded in mystery, Stonehenge continues to capture the imaginations of people all over the world.

6. The Taj Mahal (Agra, India)

Type: Clearly defined landscape

The Taj Mahal is more than just a tomb. It is an expression of love, artistry, and religious devotion.

Built by the Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan in memory of his late wife Mumtaz Mahal, the Taj Mahal is one of the most iconic buildings in the world. Its white marble exterior and intricate Islamic calligraphy make it a truly unique work of art.

But the Taj Mahal is also a powerful symbol of love and loss. For centuries, it has been seen as a monument to the ultimate sacrifice a man can make for his wife.

As such, it has become one of the most popular tourist destinations in India, drawing visitors from all over the world.

7. The Easter Island Statues (Chile)

The Easter Island statues, also known as Moai, have intrigued people for years. These monolithic sculptures are some of the most recognizable symbols of Easter Island. But what the cultural significance of these statues is not entirely cleary.

The first theory is that they were created to honor deceased ancestors of the Rapa Nui. These indigenous people believed that the dead had a powerful mana, or spiritual energy.

By erecting statues in their honor, they could harness this energy and use it to protect their crops and ensure a good harvest.

Another theory suggests that the statues were meant to symbolize power and prestige. The Easter Island inhabitants were fiercely competitive, and commissioning a statue was a way for ruling chiefs to show their wealth and status.

8. The Giza Pyramids (Egypt)

The Giza Pyramids are some of the most iconic structures in the world, and they have been the subject of numerous studies by archaeologists and historians.

These massive structures were built over 4,500 years ago, during the reign of the Pharaohs in ancient Egypt. It is generally believed that they were used as tombs for Pharaohs and their consorts. The Giza Pyramids are also considered to be one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, and they continue to be a popular tourist destination today.

In addition to their historical significance, the Giza Pyramids also hold a great deal of cultural significance for the people of Egypt. They are seen as a symbol of the power and greatness of the Pharaohs, and they are revered as a sacred site.

9. The Great Mosque of Djenne (Mali)

The Great Mosque of Djenne is the largest mud brick building in the world and a masterpiece of Sudanese architecture. Built in the 13th century, it is an important symbol of Islamic culture and a popular tourist destination.

The mosque’s towering minarets, graceful arches, and intricate details are evidence of the skill of its builders. It is also a testament to the strength of mud brick construction; despite being hundreds of years old, the mosque is still in use today.

For many visitors, the Great Mosque of Djenne is a reminder of the beauty and power of Islamic art and architecture. For Muslims, it is a place of worship and prayer, a sacred space where they can connect with God.

10. The Leaning Tower of Pisa (Italy)

The leaning tower of Pisa is one of the most iconic structures in the world. For centuries, it has been a symbol of Italian culture and a source of national pride.

Today, it is also one of the most popular tourist destinations in Italy.

Every year, millions of people from all over the world flock to see the tower, which leans at an angle of nearly four degrees due to its foundation being built on soft ground.

The tower has been carefully preserved and monitored over the years, and its lean has actually been slightly reduced in recent years. Despite this, it remains one of the most fascinating man-made towers that sits on a heritage landscape.

11. Angkor Wat (Cambodia)

Angkor Wat is a temple complex in Cambodia and one of the largest religious monuments in the world.

Built in the 12th century, it was originally constructed as a Hindu temple dedicated to the god Vishnu. However, it was later converted into a Buddhist temple, and it remains an important site of pilgrimage for Buddhists today.

Angkor Wat is also significant for its incredible size and scale. Spanning more than 162 acres, it is one of the largest religious complexes in the world.

Additionally, its intricate carvings and detailed stonework are without equal. As a result, Angkor Wat is considered to be one of the most impressive architectural achievements in human history.

12. Niagra Falls (United States and Canada)

For centuries, Niagra Falls has been a popular destination for both Native Americans and European settlers. The falls were originally known as “Thundering Waters” by the Iroquois tribe, and they held the falls in high regard as a sacred site.

In 1678, Father Louis Hennepin became the first European to see the falls, and his description of them as “the most wonderful thing in nature” helped to increase their popularity as a tourist destination.

Today, Niagra Falls is one of the most visited natural attractions in North America, and its beauty continues to inspire wonder and awe. The falls also play an important role in the regional economy, attracting millions of tourists each year and supporting countless businesses.

13. The Acropolis of Athens (Greece)

The Acropolis of Athens is an ancient citadel located on a hill in the city of Athens. The Acropolis includes the remains of several ancient buildings, most notably the Parthenon, the Temple of Athena Nike, and the Erechtheion.

The Acropolis was originally built as a fortress to protect the city of Athens from invaders. However, over time, it became a symbol of Greek culture and civilization. The Acropolis was home to some of the most important temples and monuments of Ancient Greece.

Today, the Acropolis is one of the most popular tourist destinations in Greece. It is also a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

14. The Lake District (England)

The Lake District is a National Park in North West England. Covering an area of 885 square miles, the park is the largest of the thirteen National Parks in England and Wales.

It is also the second-largest protected landscape in the United Kingdom after the Cairngorms National Park. The area was designated a National Park in 1951, and it is now also a World Heritage Site.

The park is home to 12 main lakes, as well as numerous tarns, rivers, and waterfalls. The total length of coastline within the park is approximately 71 miles. The highest mountain in England, Scafell Pike, is located within the park boundaries.

The Lake District has been a popular tourist destination for over 200 years, and it continues to be one of the most popular areas in the country for outdoor activities such as walking, climbing, and kayaking.

The area is also popular with photographers and painters due to its scenic beauty. The region was an important source of inspiration for the Romantic poets of the 18th and 19th centuries, including William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge.

15. The Lavaux Vineyards (Switzerland)

The Lavaux Vineyards are a treasured cultural heritage site in Switzerland that is known for its stunning views and unique terraced vineyards.

The vineyards are located on the slopes of Lake Geneva and date back to the 11th century. They were originally planted by monks as a way to produce wines for religious ceremonies.

Today, the Lavaux Vineyards are a popular tourist destination and produce some of Switzerland’s finest wines.

The terraced vineyards are a sight to behold, and the wines produced here are renowned for their quality. They offer a unique glimpse into Switzerland’s rich history and culture, making them an essential stop for any traveler to the country.

Cultural landscapes can be found all over the world, and they often reflect the local culture and values of the people who live there. In many cases, cultural landscapes are also important historical sites, providing insight into the way different cultures have lived and changed over time.

As a result, it’s important for societies worldwide to protect and preserve cultural landscapes that reveal important information about culture and tradition. For example, Aboriginal groups have banned hiking up Uluru in order to preserve the giant rock which has special relevance to Aboriginal culture.

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ Free Social Skills Worksheets

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 10 Reasons you’re Perpetually Single

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 20 Montessori Toddler Bedrooms (Design Inspiration)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 21 Montessori Homeschool Setups

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Cultural Landscape

Introduction.

- Short Works

- Reference Resources

- Methods for Reading and Interpreting the Landscape

- Symbolic Landscapes

- Landscape and Identity Politics

- Urban and Industrial Landscapes

- Cultural Landscapes and the Natural Environment

- Landscapes in Transition

- Classic Essays

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Cultural Geography

- Geographies of Music, Sound, and Auditory Culture

- Settlement Geography

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Indigeneity

- Geography Faculty Development

- Urban Greening

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Cultural Landscape by Sara Beth Keough LAST REVIEWED: 29 November 2022 LAST MODIFIED: 29 November 2022 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199874002-0011

The cultural landscape, the imprint of people and groups on the land, has long been of interest to geographers. The practice of “reading” and interpreting the landscape can prove difficult because most people are not used to taking a critical look at what they see. Geographers such as Carl Sauer and Peirce Lewis believe that most of our marks on the land could be considered unconscious or subliminal. More recently, however, landscape scholars such as Don Mitchell have proposed that human action on the land is quite purposeful and controlling in an effort to convey particular messages. The initial 20th-century Sauerian approach to landscape studies focused mostly on description of rural areas and was centered around cultural products (artifacts), rather than the processes that created those products. The social movements of 1960s and 1970s, however, brought about a change in the way geographers studied the landscape because of the highly urbanized nature of society. Scholars realized that urban areas now held as many or more clues to modernizing culture as did rural ones. It was also during this time that representational cultural geography emerged in an era where sign, symbol, and meaning in the landscape and the processes of cultural landscape creation became important considerations. Furthermore, the study of cultural landscapes was deemed an interdisciplinary pursuit. The post-1960s era was also the beginning of the cultural turn away from positivist empiricism. Beginning in the mid- to late 1990s, cultural geography experienced another shift, this time toward nonrepresentational approaches to studying people and place. This shift emphasized the importance of practices and experiences rather than things and called for a consideration of social reproduction and context in the process of landscape analysis. Scholars who criticized the nonrepresentational approach for assuming experiences could be isolated from images proposed the rerepresentational approach, where things, theories, and experiences are all considered equally. These shifts, however, were anything but seamless. Each shift came with arguments contesting new ideas and rethinking old ones. Today, scholars of the cultural landscape consider both the theories of landscape creation, the physical objects in the landscape, and how issues of power, inequality, and social justice play out in the landscape. Furthermore, it is assumed that one cannot study the cultural landscape without considering how humans have shaped the land and the neo-environmentalist approach that considers how the environment impacts people.

General Overviews

One of the advantages of engaging in a scholarly study of the cultural landscape is that literature is available for everyone from the beginner to the advanced academic. For students, Wallach 2005 is a good place to start for a better understanding of the history of landscape study as well as contemporary approaches, with clear examples throughout. For an advanced lesson in critical observation, use Stigloe 2018 . Jackson 1984 is a good collection of reflections by the author. For books that emphasize the late-20th- and early-21st-century of landscape research, Malpas 2011 and Howard 2011 are helpful. For both beginning and advanced scholars, Meinig 1979 is an accessible work that gives examples of often-overlooked common occurrences in the landscape and what those say about local culture. For the latest theoretical approach to landscape studies, start with Mitchell 2000 , which considers power and inequality in the landscape. Taylor and Lennon 2012 is good for its international content, as well as the authors’ emphasis on social justice and minority groups.

Howard, Peter. An Introduction to Landscape . Aldershot, UK: Ashgate, 2011.

Anthropological in its focus, this is one of the most important monographs since the “cultural turn” of the 1990s. Asks the reader to reflect on his or her own attitudes and actions in space. Examples are Eurocentric and are often taken from landscapes near the author’s home in southwest England. Written in an accessible style with many images.

Jackson, John Brinkerhoff. Discovering the Vernacular Landscape . New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1984.

Based on lectures Jackson gave between 1974 and 1984. Focuses on common elements in the landscape (and on rural areas more than urban ones) to help one better understand American history and culture. Considers how the mobility of people and goods shapes the landscape. Considered a foundational work in landscape studies.

Malpas, Jeff, ed. The Place of Landscape: Concepts, Contexts, Studies . Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press, 2011.

Considers landscape as it relates to place. Emphasizes the importance of both time and space, rather than just the visual elements of an area. Asks how landscapes become areas of inclusion or exclusion and how they have changed over time.

Meinig, Donald W., ed. The Interpretation of Ordinary Landscapes: Geographical Essays . New York: Oxford University Press, 1979.

A “must have” book for any landscape scholar, this contains works by key landscape theorists, including J. B. Jackson, Peirce F. Lewis, Yi-Fu Tuan, David Lowenthal, and the editor himself. Chapters focus on ways of analyzing the landscape by looking for clues about local culture.

Mitchell, Donald. Cultural Geography: A Critical Introduction . Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2000.

DOI: 10.1017/CBO9780511606786

The second section of this book focuses specifically on new trends in cultural landscape studies that consider themes of power, social control, gender, race, and inequality in the landscape. Written in an accessible style, author’s ideas are illustrated through clear examples. Promotes the idea that landscapes are purposefully created.

Stigloe, John R. What Is Landscape? Boston: Boston University Press, 2018.

An exploration of landscape as a noun. Leads the reader in the practice of critically looking at one’s surroundings and asking key questions. Examples help readers connect words to things.

Taylor, Ken, and Jane Lennon, eds. Managing Cultural Landscapes . New York: Routledge, 2012.

A new work that documents the changing approach to landscape studies, from a focus on monuments and historic places of the 1950s and 1960s to new critical considerations. Much emphasis is put on the Asia-Pacific region from this interdisciplinary group of contributors from universities around the world.

Wallach, Bret. Understanding the Cultural Landscape . New York: Guilford, 2005.

Good for undergraduate students, the book traces the human imprint on the land from early human civilization to the early twenty-first century. Includes a section on reading landscapes, and the emphasis is on what humans have done to landscapes and what that says about contemporary societies worldwide.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Geography »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Abortion, Geographies of

- Accessing and Visualizing Archived Weather and Climate Dat...

- Activity Space

- Actor Network Theory (ANT)

- Age, Geographies of

- Agent-based Modeling

- Agricultural Geography

- Agricultural Meteorology/Climatology

- Animal Geographies

- Anthropocene and Geography, The

- Anthropogenic Climate Change

- Applied Geography

- Arctic Climatology

- Arctic, The

- Art and Geography

- Assessment in Geography Education

- Atmospheric Composition and Structure

- Automobility

- Aviation Meteorology

- Beer, Geography of

- Behavioral and Cognitive Geography

- Belt and Road Initiative

- Biodiversity Conservation

- Biodiversity Gradients

- Biogeography

- Biogeomorphology and Zoogeomorphology

- Biometric Technologies

- Biopedoturbation

- Body, Geographies of the

- Borders and Boundaries

- Brownfields

- Carbon Cycle

- Carceral Geographies

- Cartography

- Cartography, History of

- Cartography, Mapping, and War

- Chicago School

- Children and Childhood, Geographies of

- Citizenship

- Climate Literacy and Education

- Climatology

- Community Mapping

- Comparative Urbanism

- Conservation Biogeography

- Consumption, Geographies of

- Crime Analysis, GIS and

- Crime, Geography of

- Critical GIS

- Critical Historical Geography

- Critical Military Geographies

- Cultural Ecology and Human Ecology

- Cultural Landscape

- Cyberspace, Geography of

- Desertification

- Developing World

- Development, Regional

- Development Theory

- Disability, Geography of

- Disease, Geography of

- Drones, Geography of

- Drugs, Geography of

- Economic Geography

- Economic Historical Geography

- Edge Cities and Urban Sprawl

- Education (K-12), Geography

- El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO)

- Elderly, Geography and the

- Electoral Geography

- Empire, Geography and

- Energy, Geographies of

- Energy, Renewable

- Energy Resources and Use

- Environment and Development

- Environmental Electronic Sensing Systems

- Environmental Justice

- Ethics, Geographers and

- Ethics, Geography and

- Ethnography

- Ethnonationalism

- Everyday Life, Geography and

- Extreme Heat

- Family, Geographies of the

- Feminist Geography

- Film, Geography and

- Finance, Geography of

- Financial Geographies of Debt and Crisis

- Fluvial Geomorphology

- Folk Culture and Geography

- Future, Geographies of the

- Gender and Geography

- Gentrification

- Geocomputation in Geography Education

- Geographic Information Science

- Geographic Methods: Archival Research

- Geographic Methods: Discourse Analysis

- Geographic Methods: Interviews

- Geographic Methods: Life Writing Analysis

- Geographic Methods: Visual Analysis

- Geographic Thought (US)

- Geographic Vulnerability to Climate Change

- Geographies of Affect

- Geographies of Diplomacy

- Geographies of Education

- Geographies of Resilience

- Geography and Class

- Geography Education, GeoCapabilities in

- Geography, Gramsci and

- Geography, Legal

- Geography of Biofuels

- Geography of Food

- Geography of Hunger and Famine

- Geography of Industrialization

- Geography of Public Policy

- Geography of Resources

- Geopolitics

- Geopolitics, Energy and

- Geospatial Artificial Intelligence (GeoAI)

- GIS and Computational Social Sciences

- GIS and Health

- GIS and Remote Sensing Applications in Geomorphology

- GIS and Virtual Reality

- GIS applications in Human Geography

- GIS, Ethics of

- GIS, Geospatial Technology, and Spatial Thinking in Geogra...

- GIS, Historical

- GIS, History of

- GIS, Space-Time

- Glacial and Periglacial Geomorphology

- Glaciers, Geography of

- Globalization

- Health Care, Geography of

- Hegemony and Geographic Knowledge

- Historical Geography

- Historical Mobilities

- Histories of Protest and Social Movements

- History, Environmental

- Homelessness

- Human Dynamics, GIScience of

- Human Geographies of Outer Space

- Human Trafficking

- Humanistic Geography

- Human-Landscape Interactions

- Humor, Geographies of

- Hydroclimatology and Climate Variability

- Identity and Place

- "Imagining a Better Future through Place": Geographies of ...

- Immigration and Immigrants

- Indigenous Peoples and the Global Indigenous Movement

- Informal Economy

- Innovation, Geography of

- Intelligence, Geographical

- Islands, Human Geography and

- Justice, Geography of

- Knowledge Economy: Spatial Approaches

- Knowledge, Geography of

- Labor, Geography of

- Land Use and Cover Change

- Land-Atmosphere Interactions

- Landscape Interpretation

- Literature, Geography and

- Location Theory

- Marine Biogeography

- Marine Conservation and Fisheries Management

- Media Geography

- Medical Geography

- Migration, International Student

- Military Geographies and the Environment

- Military Geographies of Popular Culture

- Military Geographies of Urban Space and War

- Military Geography

- Moonsoons, Geography of

- Mountain Geography

- Mountain Meteorology

- Music, Sound, and Auditory Culture, Geographies of

- National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) in Geog...

- Nations and Nationalism

- Natural Hazards and Risk

- Nature-Society Theory

- Neogeography

- New Urbanism

- Non-representational Theory

- Nuclear War, Geographies of

- Nutrition Transition, The

- Orientalism and Geography

- Participatory Action Research

- Peace, Geographies of

- Pedagogical Content Knowledge in Geography Education

- Perspectives in Geography Internships

- Phenology and Climate

- Photographic and Video Methods in Geography

- Physical Geography

- Polar Geography

- Policy Mobilities

- Political Ecology

- Political Geography

- Political Geology

- Popular Culture, Geography and

- Population Geography

- Ports and Maritime Trade

- Postcolonialism

- Postmodernism and Poststructuralism

- Pragmatism, Geographies of

- Producer Services

- Psychogeography

- Public Participation GIS, Participatory GIS, and Participa...

- Qualitative GIS

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods in Human Geography

- Questionnaires

- Race and Racism

- Refugees, Geography of

- Religion, Geographies of

- Retail Trade, Geography of

- Rural Geography

- Science and Technology Studies (STS) in Geography

- Sea-Level Research, Quaternary

- Security and Securitization, Geographies of

- Segregation, Ethnic and Racial

- Service Industries, Geography of

- Sexuality, Geography of

- Slope Processes

- Social Justice

- Social Media Analytics

- Soils, Diversity of

- Sonic Methods in Geography

- Spatial Analysis

- Spatial Autocorrelation

- Sports, Geography of

- Sustainability Education at the School Level, Geography an...

- Sustainability Science

- Sustainable Agriculture

- Synoptic Climatology

- Technological Change, Geography of

- Telecommunications

- Teleconnections, Atmospheric

- Terrestrial Snow, Measurement of

- Territory and Territoriality

- Terrorism, Geography of

- The Climate Security Nexus

- The Voluntary Sector and Geography

- Time, Geographies of

- Time Geography

- Time-Space Compression

- Tourism Geography

- Touristification

- Transnational Corporations

- Unoccupied Aircraft Systems

- Urban Geography

- Urban Heritage

- Urban Historical Geography

- Urban Meteorology and Climatology

- Urban Planning and Geography

- Urban Political Ecology

- Urban Sustainability

- Visualizations

- Vulnerability, Risk, and Hazards

- Vulnerability to Climate Change

- War on Terror, Geographies of the

- Weather and Climate Damage Studies

- Whiteness, Geographies of

- Wine, Geography of

- World Cities

- Young People's Geography

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|81.177.182.159]

- 81.177.182.159

Cultural Landscape Essay Example

- Pages: 6 (1464 words)

- Published: August 8, 2017

- Type: Essay

A cultural landscape is a piece of land that possesses natural and cultural resources related to an historic event. individual. or group of people. They are normally semisynthetic lexis of relationships with the nature and/or society or civilization. These can include expansive estates. public gardens and Parkss. educational establishments. graveyards. main roads. and industrial sites. Cultural landscapes are besides humanist plants of art. texts and narrations of civilizations that express regional and cultural individuality.

They besides present relationship to their ecological position. Human activities have turned out to be a major cause of determining most cultivated landscapes on the surface of Earth. Human. animate being and machine labour expended in utilizing the land can make outstanding cultural landscapes with high aesthetic. cultural and ecological value such as the paddy-field rice patios of south-east A

sia. but may every bit good consequence in land debasement as is the instance in some parts in the Mediterranean.

The distribution of landforms such as steep inclines. fertile fields. inundated vales in a landscape sets the frame for land usage by finding factors such as handiness. H2O and alimentary handiness. but may over long periods of clip besides be changed through land usage. On the other manus. land usage serves distinguishable socio-economic intents: land may provide stuffs and energy through runing. agribusiness or forestry. it may host substructure. or it may be needed to absorb waste and emanations ( Haberl et al.

. 2004 ) . Landscapes can be seen as the contingent and historically variable result of this interplay between socio-economic and biophysical forces. During the development of cultural landscapes throughout the universe. worlds have developed adaptative land-use techniques and created specific form

of Fieldss. farmsteads. remnant woodlots and the similar that depended on both natural and socio-economic conditions.

In European agricultural landscapes. the long history of land transmutation has led to regionally distinct regular forms of geometrically arranged landscape elements. reflecting the historical and cultural background of the predominating land-use system of a part ( Bell. 1999 ) . The spacial distribution of ecotopes. the alleged landscape construction. has hence frequently been regarded as a mosaic of ‘frozen processes’ ; i. e. landscape construction assumedly mirrors the procedures which had been traveling on in a landscape.

This perceptual experience has even become a cardinal paradigm in modern landscape ecology. While many ecosystem procedures are hard to detect straight. landscape construction can be derived from function every bit good as from remote-sensing informations ; hence. landscape construction was frequently non merely used to measure the ecological value of landscapes. but besides to judge ecological facets of the sustainability of land-use forms ( Wrbka et al. . 1999b ) . The Influence Of Land Form On The Intensity Of Land Use Cultural landscapes have. in contrast to natural and semi-natural landscapes. particular features.

The perturbation government every bit good as the major stuff and energy fluxes in these transformed landscapes is controlled to a big extent by worlds. This is done by the different land-use patterns applied for hayfields. cultivable land or woods. Decisions about land usage are made harmonizing to the local agro-ecological features which are nested in a hierarchy of societal. economical and proficient restraints. Cultural landscapes can therefore merely be understood by analysing the interplay between biophysical and socioeconomic forms and procedures. Landscape Structure And Intensity Of Land Use

and Turner ( 1989 ) found that the landscape elements of the Georgia landscape in the early 1930s had a higher fractal dimension than the elements of the same part in the 1980s. During the same period of clip the usage of fertilisers. pesticides and other agrochemicals increased dramatically. This illustrates that the turning human impact on the land may ensue in a landscape with diminishing geometrical complexness. Human activities introduce oblongness and rectilinearity into landscapes. bring forthing regular forms with consecutive boundary lines ( Forman. 1999 ; Forman and Moore. 1992 ) .

Assorted surveies suggest that the rate of landscape transmutation is a map of land-use strength ( Alard and Poudevigne. 1999 ; Hietala-Koivu. 1999 ; Mander et Al. . 1999 ; Odum and Turner. 1989 ) . and that the geometric complexness of a landscape in peculiar lessenings with increasing land-use strength accompanied by a lessening of habitat heterogeneousness and an addition of production units. Using the thermodynamic Torahs to landscape construction. Forman and Moore ( 1992 ) suggested that the concentrated input of energy ( e. g.

. by tractor plowing. works production. wildfire ) decreases the information of spots compared to adjacent countries and green goodss directly and disconnected boundaries. In other words. energy is required to change over natural curvilineal boundaries into consecutive lines and energy is required to keep them. The decrease of the energy input additions entropy and revegetation convolutes and softens landscape boundaries. This means that the ‘landscape structure’ . in the sense of Forman and Godron ( 1986 ) . can be regarded as ‘frozen processes’ . Landscape Structure And Biodiversity

Many studies show that species profusion of

vascular workss and nonvascular plants usually decreases with land-use strength ( Luoto. 2000 ; Mander et Al. . 1999 ; Zechmeister and Moser. 2001 ; Zechmeister et Al. . 2003 ) . As the nexus between landscape construction and land-use strength could be established. form complexness as a step of land-use strength seems to be besides a good forecaster of species profusion ( Moser et al. . 2002 ; Wrbka et Al. . 1999a ) . Consequently. higher species richness in countries with high LD and profusion values can be expected.

The usage of form complexness indices as indexs for works species profusion is based on an false correlativity between geometric landscape complexness and biodiversity ( Moser et al. . 2002 ) . Obviously. this correlativity is non mechanistic but it is supposed to be due to congruous effects of land-use strength on landscape form complexness and species profusion. Moser et Al. ( 2002 ) gives a good literature overview about the drive factors responsible for the lessening of landscape complexness with increasing land-use strength. which resulted in the undermentioned cardinal findings:

* The bulk of landscape elements in agricultural landscapes are designed by worlds as rectangles with consecutive and distinguishable boundaries ( Forman. 1999 ) . * Outside boundaries of semi-natural or natural spots are straightened by neighbouring cultivated countries ( ) . * Increasing land-use strength is accompanied by a lessening of semi-natural and natural countries ( Alard and Poudevigne. 1999 ; Mander et Al. . 1999 ) . ensuing in a lessening of natural curvilineal boundaries.

* Intensification in agribusiness tends to increase the size of production units ( Alard and Poudevigne. 1999 ; Hietala-Koivu.

1999 ) . In add-on to that intensification of land usage on the production unit. e. g. . by fertilising or increased mowing strength. besides leads to a dramatic lessening of the species profusion ( Zechmeister et al. . 2003 ) . The description of the debasement of semi-natural and agricultural landscapes shows clearly the mutuality of biodiversity and landscape heterogeneousness. induced by closely interlacing ecological. demographical. socio-economic and cultural factors.

For an effectual preservation direction of biodiversity and landscape eco-diversity. a clear apprehension of the ecological and cultural procedures and their disturbances is indispensable. Intermediate perturbation degrees lead to a extremely complex and diverse cultural landscape which can host many works and carnal species. Landscapes. with ‘eco-diversity hotspots’ . can be regarded as intimation for ‘biodiversity hotspots’ . Landscape pattern indexs hence play an of import function for landscape preservation planning. The apprehension of landscape procedures is important for the preservation of both. landscape eco-diversity and biodiversity.

Decisions From a preservation biological science point of position. the on-going procedure of familial eroding and biodiversity loss every bit good as the replacing of specific recognizable cultural landscapes by humdrum ubiquistic production sites will go on. The biophysical features and natural restraints of the investigated landscapes are interwoven with the regional historic and socio-economical development. This interplay is the background for the development of a assortment of cultural landscapes which have their ain specific features. Geo-ecological land-units provide one solution.

This is of particular importance when the relationship of landscape forms and implicit in procedures is under probe. Works Cited Alard. D. . Poudevigne. I. Factors commanding works diverseness in rural landscapes: a functional attack. Landscape and Urban Planning.

1999: 46. 29–39 Bell. S. . Landscape—Pattern. Perception and Process. E. & A ; F. N. Spon. London. 1999 Forman. R. T. T. . & A ; Godron. M. Landscape Ecology. Wiley. New York. 1986. Forman. R. T. T. . & A ; Moore. P. N. Theoretical foundations for understanding boundaries in landscape mosaics.

In: Hansen. F. J. . Castri. F. ( Eds. ) . Landscape Boundaries. Consequences for Biotic Diversity and Ecological Flows. Springer. New York. 1992. pp. 236–258. Forman. R. T. T. Horizontal processes. roads. suburbs. social aims in landscape ecology. In: Klopatek. M. . Gardner. R. H. ( Eds. ) . Landscape Ecological Analysis: Issues and Applications. Springer. New York. 1999. pp. 35–53. Haberl. H. . Wackernagel. M. . Krausmann. F. . Erb. K. -H. . Monfreda. C. Ecological footmarks and human appropriation of net primary production: A comparing.

Land Use Policy. doi:10. 1016/ j. landusepol. 2003. 10. 008. . 2004 Hietala-Koivu. R. Agricultural landscape alteration: a instance survey in Y lane. Southwest Finland. Landscape and Urban Planning. 1999: 46. 103–108. Luoto. M. . Modelling of rare works species richness by landscape variables in an agribusiness country in Finland. Plant Ecology. 2000: 149. 157–168. Mander. U. . Mikk. M. . Ku. lvik. M. . Ecological and low strength agribusiness as subscribers to landscape and biological diverseness. Landscape and Urban Planning. 1999: 46. 169–177.

- Purring monkey among hundreds of new animals found in Amazon rainforest news Essay Example

- Unocini, an Ecological Approach Essay Example

- Benefits of Ecotourism Essay Example

- SWOT Analysis of Protected Area Management Essay Example

- Sustainable Development Analysis Essay Example

- Unity In Diversity Analysis Narrative Essay Example

- Global Percepetive On Environmental Issues Essay Example

- How Is the Fool Presented in 'King Lear'? Essay Example

- Columbus and Indians Essay Example

- Jerry Mcguire Essay Example

- Theme Paragraph Example Essay Example

- Financial plans Essay Example

- Case Tools Essay Example

- Coun 510 Db Forum#2 Essay Example

- The Lamp at Noon Essay Example

- Environmental Disaster essays

- Sustainable Development essays

- Atmosphere essays

- Biodiversity essays

- Coral Reef essays

- Desert essays

- Earth essays

- Ecosystem essays

- Forest essays

- Lake essays

- Natural Environment essays

- Ocean essays

- Oxygen essays

- Rainbow essays

- Soil essays

- Volcano essays

- Water essays

- Wind essays

- John Locke essays

- 9/11 essays

- A Good Teacher essays

- A Healthy Diet essays

- A Modest Proposal essays

- A&P essays

- Academic Achievement essays

- Achievement essays

- Achieving goals essays

- Admission essays

- Advantages And Disadvantages Of Internet essays

- Alcoholic drinks essays

- Ammonia essays

- Analytical essays

- Ancient Olympic Games essays

- Arabian Peninsula essays

- Argument essays

- Argumentative essays

- Atlantic Ocean essays

- Auto-ethnography essays

- Autobiography essays

- Ballad essays

- Batman essays

- Binge Eating essays

- Black Power Movement essays

- Blogger essays

- Body Mass Index essays

- Book I Want a Wife essays

- Boycott essays

Haven't found what you were looking for?

Search for samples, answers to your questions and flashcards.

- Enter your topic/question

- Receive an explanation

- Ask one question at a time

- Enter a specific assignment topic

- Aim at least 500 characters

- a topic sentence that states the main or controlling idea

- supporting sentences to explain and develop the point you’re making

- evidence from your reading or an example from the subject area that supports your point

- analysis of the implication/significance/impact of the evidence finished off with a critical conclusion you have drawn from the evidence.

Unfortunately copying the content is not possible

Tell us your email address and we’ll send this sample there..

By continuing, you agree to our Terms and Conditions .

Robert Heslip Blog

Thoughts on landscape design

Exploring the Concept of Cultural Landscape and Sense of Place

Delving into the intricacies of human civilization, community, and emotional connection to surroundings , we uncover the profound impact of culture on the physical environment. Examining the intertwining of heritage, traditions, and personal experiences within a geographic space , we gain insight into the profound sense of belonging and identity that individuals develop towards their surroundings.

Through the lens of cultural landscapes and the profound sense of place they evoke , we can observe the intricate layers of history, values, and social dynamics that shape our understanding of the world. By exploring the emotional resonance and deep-rooted connections that individuals form with their environment , we begin to appreciate the significance of cultural identity in shaping our perceptions and experiences.

The Historical Evolution of Cultural Landscapes

Over time, the development and transformation of landscapes have been deeply intertwined with human activities and societal changes. The historical evolution of these landscapes reflects the intricate relationship between people and their environment, illustrating the way in which cultures have shaped and been shaped by the land they inhabit. Through a lens of time, we can observe the dynamic nature of cultural landscapes as they have evolved through generations, preserving the essence of past civilizations while adapting to the ever-changing demands of the present.

From ancient civilizations to modern societies, the notion of cultural landscapes has evolved alongside human civilization. The landscapes that once served as sacred grounds for rituals and ceremonies have transformed into urban metropolises bustling with activity. The agricultural practices of yesteryears have given way to industrial complexes and technological advancements, altering the very fabric of the land. Despite these changes, traces of history can still be found in the architecture, art, and customs that continue to define the cultural landscape of today.

Through the lens of history, we can gain a deeper understanding of the layers of meaning embedded within cultural landscapes. Each era leaves its mark on the land, turning it into a living tapestry of human experiences and memories. The historical evolution of cultural landscapes serves as a testament to the resilience and adaptability of societies, showcasing the ability of communities to thrive and innovate in the face of challenges and transformations.

Defining Sense of Place in Cultural Landscapes

In the realm of cultural environments and geographical settings shaped by human activities and interactions, there exists a profound connection between individuals and their surroundings. This bond is multifaceted, encompassing emotional, spiritual, and societal elements that contribute to a unique sense of identity and belonging. This intricate relationship between people and their environment is often referred to as a sense of place.

At its core, a sense of place is an individual’s perception and emotional attachment to a specific location or environment. It goes beyond physical characteristics and geographical features, delving into the intangible qualities that evoke memories, emotions, and a strong sense of belonging. It is a subjective experience that is deeply rooted in personal and collective histories, cultural traditions, and social interactions.

Understanding the concept of sense of place in cultural landscapes requires a nuanced exploration of the ways in which individuals engage with their surroundings, interpret their experiences, and form meaningful connections with the spaces they inhabit. It involves recognizing the significance of cultural heritage, traditions, rituals, and narratives in shaping our perceptions and interactions with the built and natural environment.

The Role of Memory and Identity

Our past experiences, personal stories, and cultural heritage play a crucial role in shaping our sense of self and belonging. Memory serves as a vessel through which we can access the essence of who we are, connecting us to our roots and allowing us to navigate the complexities of identity. By delving into the depths of our memories, we can uncover layers of meaning and significance that contribute to our understanding of ourselves and our place in the world.

The Power of Collective Memory

Collective memory, formed through shared experiences and historical narratives, binds communities together and anchors them in a common identity. The stories we pass down from generation to generation serve as a bridge between the past, present, and future, preserving our cultural heritage and instilling a sense of continuity and belonging. Through the collective memory, we can find strength, resilience, and a shared sense of purpose that unites us in times of adversity.

Exploring Cultural Landscapes Through Art and Literature

Delving into the diverse expressions of various societies and their environments through creative means offers a unique perspective on the interconnectedness of culture, art, and literature. Through the lens of artistic and literary works, we can uncover deep insights into the values, traditions, and identities that shape different cultural landscapes.

Art serves as a powerful medium for capturing the essence of cultural landscapes, as artists have the ability to visually interpret and represent the tangible and intangible aspects of a place. Paintings, sculptures, and installations can evoke a sense of belonging and nostalgia, reflecting the intricate details of a particular environment and the emotions associated with it.

Similarly, literature provides a narrative exploration of cultural landscapes, offering a textual representation of the human experience within a specific context. Through stories, poems, and essays, authors can weave intricate tapestries of imagery and language that illuminate the nuances of a place and its significance to those who inhabit it.

By analyzing and interpreting artistic and literary works that engage with cultural landscapes, we gain a deeper understanding of the ways in which societies interact with their surroundings and the meanings they attach to their environment. Through this exploration, we can appreciate the richness and complexity of cultural diversity and the profound impact of place on individual and collective identities.

The Influence of Nature and Environment

In the realm of the natural world and surroundings, the impact on cultural landscapes and people’s sense of belonging is profound. Nature and the environment play a crucial role in shaping the identity of a place, influencing the way people interact with their surroundings and develop a connection to the land.

Natural Elements and Cultural Identity

The natural elements present in a particular region, such as climate, flora, and fauna, are essential components of its cultural identity. The way in which people interact with and adapt to their environment shapes their traditions, beliefs, and values, creating a unique sense of place that is closely tied to nature.

Environmental Sustainability and Cultural Preservation

As societies become more aware of the importance of environmental sustainability, the preservation of cultural landscapes becomes increasingly significant. Balancing development with conservation efforts is crucial to maintaining the integrity of cultural heritage and ensuring that future generations can continue to connect with the land in meaningful ways.

Brown, Steve: Cultural Landscape as place, process and practice

Brown, Steve: Cultural Landscape as place, process and practice by ISCCL 96 views 2 years ago 8 minutes, 45 seconds

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Aug 15, 2023 · A cultural landscape is a landscape that has cultural significance. The landscapes reflect the culture of the people who have lived there. Cultural landscapes can give human geographers information about how a culture lives, what they value, and how they interact with the land. Examples of cultural landscapes include golf courses, urban ...

journal, the cross-cultural study of cultural landscapes. I therefore begin this largely conceptual and general paper by discussing the two components of the concept: "landscape" and "cultural." "LANDSCAPE" The term cultural "landscape" is unfortunate mainly because its general, everyday usage, stemming from its origins, is

Nov 1, 2011 · Cultural landscapes are intended to increase awareness that heritage places (sites) are not isolated islands and that there is an interdependence of people, social structures, and the landscape ...

Nov 29, 2022 · The Interpretation of Ordinary Landscapes: Geographical Essays. New York: Oxford University Press, 1979. New York: Oxford University Press, 1979. A “must have” book for any landscape scholar, this contains works by key landscape theorists, including J. B. Jackson, Peirce F. Lewis, Yi-Fu Tuan, David Lowenthal, and the editor himself.

INTRODUCTION AND JUSTIFICATION Cultural landscape is an instrument of force (Mitchell, 2008) and it is knowledge (Graham, 2001). As such it represents cultural capital (Bourdieu, 1977) of a society, state or nation, where through diverse social processes and practices directly or indirectly helps to form cultural identity.

Sep 2, 2016 · Human activities have turned out to be a major cause of shaping most cultivated landscapes on the surface of Earth. Human, animal and machine labor expended in using the land can create outstanding cultural landscapes with high aesthetic, cultural and ecological value such as the paddy-field rice terraces of south-east Asia, but may as well result in land degradation as is the case in some ...

Aug 8, 2017 · of Fieldss. farmsteads. remnant woodlots and the similar that depended on both natural and socio-economic conditions. In European agricultural landscapes. the long history of land transmutation has led to regionally distinct regular forms of geometrically arranged landscape elements. reflecting the historical and cultural background of the predominating land-use system of a part ( Bell. 1999 ) .

Cultural landscape is a term used in the fields of geography, ecology, and heritage studies, to describe a symbiosis of human activity and environment.

as problem, landscape as wealth, landscape as ideology, landscape as his-tory, landscape as place, and landscape as aesthetic.3 Outside the field of cultural geography, members from the design disciplines studying the changes taking place in the cultural landscape are often more com-pelled to offer their evaluative judgments.

Oct 23, 2024 · Despite these changes, traces of history can still be found in the architecture, art, and customs that continue to define the cultural landscape of today. Through the lens of history, we can gain a deeper understanding of the layers of meaning embedded within cultural landscapes. Each era leaves its mark on the land, turning it into a living ...