- Entertainment

- General Knowledge

10 Movie Adaptions That Brought Popular Songs to Life

10 Miraculous Advances Toward Curing Incurable Diseases

10 Undeniable Signs That People’s Views of Mushrooms Are Changing

10 Strange Attempts to Smuggle Animals

10 Natural Rock Formations That Will Make You Do a Double Take

10 Actors Hidden in Your Favorite Movies

10 Science Facts That Will Change How You Look at the World

10 Incredible Female Comic Book Artists

10 Terrifying Serial Killers from Centuries Ago

10 Hilariously Over-Engineered Solutions to Simple Problems

Who's behind listverse.

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

Top 10 Unethical Psychological Experiments

Psychology is a relatively new science which gained popularity in the early 20th century with Wilhelm Wundt. In the zeal to learn about the human thought process and behavior, many early psychiatrists went too far with their experimentations, leading to stringent ethics codes and standards. Though these are highly unethical experiments, it should be mentioned that they did pave the way to induct our current ethical standards of experiments, and that should be seen as a positive. There is some crossover on this list with the Top 10 Evil Human Experiments . Three items from that list are reproduced here (items 8, 9, and 10) for the sake of completeness.

The Monster Study was a stuttering experiment on 22 orphan children in Davenport, Iowa, in 1939 conducted by Wendell Johnson at the University of Iowa. Johnson chose one of his graduate students, Mary Tudor, to conduct the experiment and he supervised her research. After placing the children in control and experimental groups, Tudor gave positive speech therapy to half of the children, praising the fluency of their speech, and negative speech therapy to the other half, belittling the children for every speech imperfection and telling them they were stutterers. Many of the normal speaking orphan children who received negative therapy in the experiment suffered negative psychological effects and some retained speech problems during the course of their life. Dubbed “The Monster Study” by some of Johnson’s peers who were horrified that he would experiment on orphan children to prove a theory, the experiment was kept hidden for fear Johnson’s reputation would be tarnished in the wake of human experiments conducted by the Nazis during World War II. The University of Iowa publicly apologized for the Monster Study in 2001.

South Africa’s apartheid army forced white lesbian and gay soldiers to undergo ‘sex-change’ operations in the 1970’s and the 1980’s, and submitted many to chemical castration, electric shock, and other unethical medical experiments. Although the exact number is not known, former apartheid army surgeons estimate that as many as 900 forced ‘sexual reassignment’ operations may have been performed between 1971 and 1989 at military hospitals, as part of a top-secret program to root out homosexuality from the service.

Army psychiatrists aided by chaplains aggressively ferreted out suspected homosexuals from the armed forces, sending them discretely to military psychiatric units, chiefly ward 22 of 1 Military Hospital at Voortrekkerhoogte, near Pretoria. Those who could not be ‘cured’ with drugs, aversion shock therapy, hormone treatment, and other radical ‘psychiatric’ means were chemically castrated or given sex-change operations.

Although several cases of lesbian soldiers abused have been documented so far—including one botched sex-change operation—most of the victims appear to have been young, 16 to 24-year-old white males drafted into the apartheid army.

Dr. Aubrey Levin (the head of the study) is now Clinical Professor in the Department of Psychiatry (Forensic Division) at the University of Calgary’s Medical School. He is also in private practice, as a member in good standing of the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Alberta.

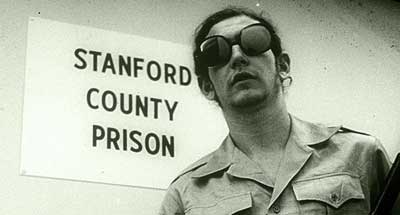

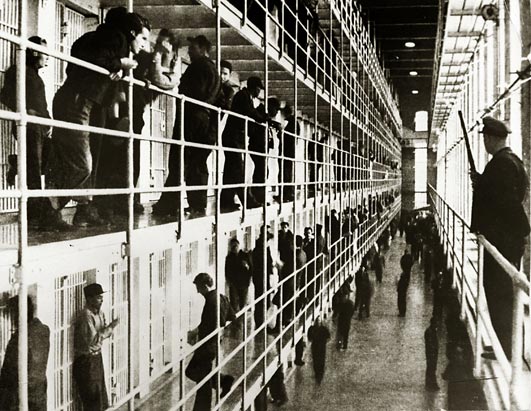

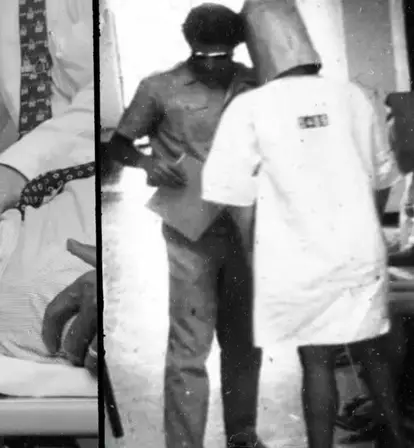

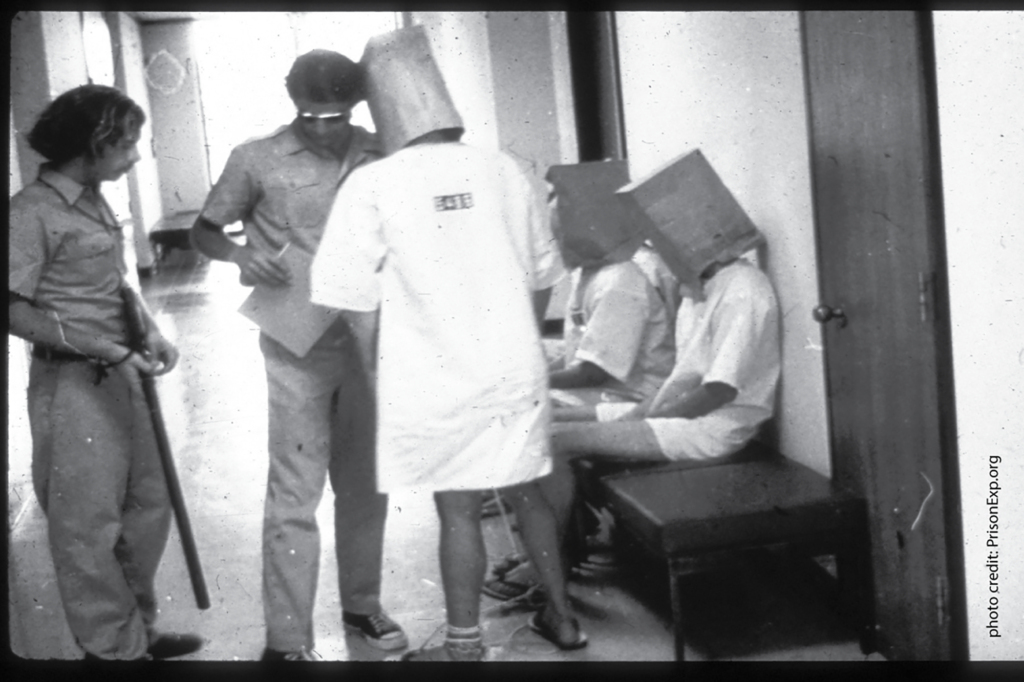

This study was not necessarily unethical, but the results were disastrous, and its sheer infamy puts it on this list. Famed psychologist Philip Zimbardo led this experiment to examine that behavior of individuals when placed into roles of either prisoner or guard and the norms these individuals were expected to display.

Prisoners were put into a situation purposely meant to cause disorientation, degradation, and depersonalization. Guards were not given any specific directions or training on how to carry out their roles. Though at first, the students were unsure of how to carry out their roles, eventually they had no problem. The second day of the experiment invited a rebellion by the prisoners, which brought a severe response from the guards. Things only went downhill from there.

Guards implemented a privilege system meant to break solidarity between prisoners and create distrust between them. The guards became paranoid about the prisoners, believing they were out to get them. This caused the privilege system to be controlled in every aspect, even in the prisoners’ bodily functions. Prisoners began to experience emotional disturbances, depression, and learned helplessness. During this time, prisoners were visited by a prison chaplain. They identified themselves as numbers rather than their names, and when asked how they planned to leave the prison, prisoners were confused. They had completely assimilated into their roles.

Dr. Zimbardo ended the experiment after five days, when he realized just how real the prison had become to the subjects. Though the experiment lasted only a short time, the results are very telling. How quickly someone can abuse their control when put into the right circumstances. The scandal at Abu Ghraib that shocked the U.S. in 2004 is prime example of Zimbardo’s experiment findings.

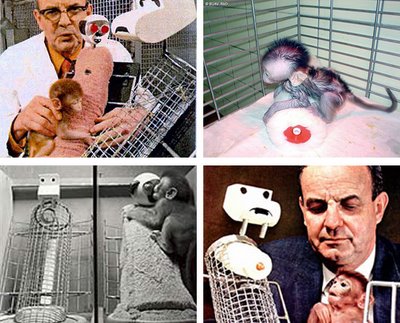

While animal experimentation can be incredibly helpful in understanding man, and developing life saving drugs, there have been experiments which go well beyond the realms of ethics. The monkey drug trials of 1969 were one such case. In this experiment, a large group of monkeys and rats were trained to inject themselves with an assortment of drugs, including morphine, alcohol, codeine, cocaine, and amphetamines. Once the animals were capable of self-injecting, they were left to their own devices with a large supply of each drug.

The animals were so disturbed (as one would expect) that some tried so hard to escape that they broke their arms in the process. The monkeys taking cocaine suffered convulsions and in some cases tore off their own fingers (possible as a consequence of hallucinations), one monkey taking amphetamines tore all of the fur from his arm and abdomen, and in the case of cocaine and morphine combined, death would occur within 2 weeks.

The point of the experiment was simply to understand the effects of addiction and drug use; a point which, I think, most rational and ethical people would know did not require such horrendous treatment of animals.

In 1924, Carney Landis, a psychology graduate at the University of Minnesota developed an experiment to determine whether different emotions create facial expressions specific to that emotion. The aim of this experiment was to see if all people have a common expression when feeling disgust, shock, joy, and so on.

Most of the participants in the experiment were students. They were taken to a lab and their faces were painted with black lines, in order to study the movements of their facial muscles. They were then exposed to a variety of stimuli designed to create a strong reaction. As each person reacted, they were photographed by Landis. The subjects were made to smell ammonia, to look at pornography, and to put their hands into a bucket of frogs. But the controversy around this study was the final part of the test.

Participants were shown a live rat and given instructions to behead it. While all the participants were repelled by the idea, fully one third did it. The situation was made worse by the fact that most of the students had no idea how to perform this operation in a humane manner and the animals were forced to experience great suffering. For the one third who refused to perform the decapitation, Landis would pick up the knife and cut the animals head off for them.

The consequences of the study were actually more important for their evidence that people are willing to do almost anything when asked in a situation like this. The study did not prove that humans have a common set of unique facial expressions.

John Watson, father of behaviorism, was a psychologist who was apt to using orphans in his experiments. Watson wanted to test the idea of whether fear was innate or a conditioned response. Little Albert, the nickname given to the nine month old infant that Watson chose from a hospital, was exposed to a white rabbit, a white rat, a monkey, masks with and without hair, cotton wool, burning newspaper, and a miscellanea of other things for two months without any sort of conditioning. Then experiment began by placing Albert on a mattress in the middle of a room. A white laboratory rat was placed near Albert and he was allowed to play with it. At this point, the child showed no fear of the rat.

Then Watson would make a loud sound behind Albert’s back by striking a suspended steel bar with a hammer when the baby touched the rat. In these occasions, Little Albert cried and showed fear as he heard the noise. After this was done several times, Albert became very distressed when the rat was displayed. Albert had associated the white rat with the loud noise and was producing the fearful or emotional response of crying.

Little Albert started to generalize his fear response to anything fluffy or white (or both). The most unfortunate part of this experiment is that Little Albert was not desensitized to his fear. He left the hospital before Watson could do so.

In 1965, psychologists Mark Seligman and Steve Maier conducted an experiment in which three groups of dogs were placed in harnesses. Dogs from group one were released after a certain amount of time, with no harm done. Dogs from group two were paired up and leashed together, and one from each pair was given electrical shocks that could be ended by pressing a lever. Dogs from group three were also paired up and leashed together, one receiving shocks, but the shocks didn’t end when the lever was pressed. Shocks came randomly and seemed inevitable, which caused “learned helplessness,” the dogs assuming that nothing could be done about the shocks. The dogs in group three ended up displaying symptoms of clinical depression.

Later, group three dogs were placed in a box with by themselves. They were again shocked, but they could easily end the shocks by jumping out of the box. These dogs simply “gave up,” again displaying learned helplessness. The image above is a healthy pet dog in a science lab, not an animal used in experimentation.

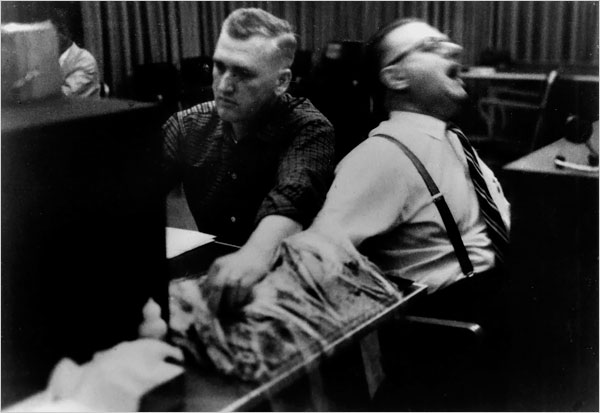

The notorious Milgrim Study is one of the most well known of psychology experiments. Stanley Milgram, a social psychologist at Yale University, wanted to test obedience to authority. He set up an experiment with “teachers” who were the actual participants, and a “learner,” who was an actor. Both the teacher and the learner were told that the study was about memory and learning.

Both the learner and the teacher received slips that they were told were given to them randomly, when in fact, both had been given slips that read “teacher.” The actor claimed to receive a “learner” slip, so the teacher was deceived. Both were separated into separate rooms and could only hear each other. The teacher read a pair of words, following by four possible answers to the question. If the learner was incorrect with his answer, the teacher was to administer a shock with voltage that increased with every wrong answer. If correct, there would be no shock, and the teacher would advance to the next question.

In reality, no one was being shocked. A tape recorder with pre-recorded screams was hooked up to play each time the teacher administered a shock. When the shocks got to a higher voltage, the actor/learner would bang on the wall and ask the teacher to stop. Eventually all screams and banging would stop and silence would ensue. This was the point when many of the teachers exhibited extreme distress and would ask to stop the experiment. Some questioned the experiment, but many were encouraged to go on and told they would not be responsible for any results.

If at any time the subject indicated his desire to halt the experiment, he was told by the experimenter, Please continue. The experiment requires that you continue. It is absolutely essential that you continue. You have no other choice, you must go on. If after all four orders the teacher still wished to stop the experiment, it was ended. Only 14 out of 40 teachers halted the experiment before administering a 450 volt shock, though every participant questioned the experiment, and no teacher firmly refused to stop the shocks before 300 volts.

In 1981, Tom Peters and Robert H. Waterman Jr. wrote that the Milgram Experiment and the later Stanford prison experiment were frightening in their implications about the danger lurking in human nature’s dark side.

Dr. Harry Harlow was an unsympathetic person, using terms like the “rape rack” and “iron maiden” in his experiments. He is most well-known for the experiments he conducted on rhesus monkeys concerning social isolation. Dr. Harlow took infant rhesus monkeys who had already bonded with their mothers and placed them in a stainless steel vertical chamber device alone with no contact in order to sever those bonds. They were kept in the chambers for up to one year. Many of these monkeys came out of the chamber psychotic, and many did not recover. Dr. Harlow concluded that even a happy, normal childhood was no defense against depression, while science writer Deborah Blum called these, “common sense results.”

Gene Sackett of the University of Washington in Seattle, one of Harlow’s doctoral students, stated he believes the animal liberation movement in the U.S. was born as a result of Harlow’s experiments. William Mason, one of Harlow’s students, said that Harlow “kept this going to the point where it was clear to many people that the work was really violating ordinary sensibilities, that anybody with respect for life or people would find this offensive. It’s as if he sat down and said, ‘I’m only going to be around another ten years. What I’d like to do, then, is leave a great big mess behind.’ If that was his aim, he did a perfect job.”

In 1965, a baby boy was born in Canada named David Reimer. At eight months old, he was brought in for a standard procedure: circumcision. Unfortunately, during the process his penis was burned off. This was due to the physicians using an electrocautery needle instead of a standard scalpel. When the parents visited psychologist John Money, he suggested a simple solution to a very complicated problem: a sex change. His parents were distraught about the situation, but they eventually agreed to the procedure. They didn’t know that the doctor’s true intentions were to prove that nurture, not nature, determined gender identity. For his own selfish gain, he decided to use David as his own private case study.

David, now Brenda, had a constructed vagina and was given hormonal supplements. Dr. Money called the experiment a success, neglecting to report the negative effects of Brenda’s surgery. She acted very much like a stereotypical boy and had conflicting and confusing feelings about an array of topics. Worst of all, her parents did not inform her of the horrific accident as an infant. This caused a devastating tremor through the family. Brenda’s mother was suicidal, her father was alcoholic, and her brother was severely depressed.

Finally, Brenda’s parents gave her the news of her true gender when she was fourteen years old. Brenda decided to become David again, stopped taking estrogen, and had a penis reconstructed. Dr. Money reported no further results beyond insisting that the experiment had been a success, leaving out many details of David’s obvious struggle with gender identity. At the age of 38, David committed suicide.

This article is licensed under the GFDL because it contains quotations from Wikipedia.

More Great Lists

- 30 Most Unethical Psychology Human Experiments

Disturbing human experiments aren’t something the average person thinks too much about. Rather, the progress achieved in the last 150 years of human history is an accomplishment we’re reminded of almost daily. Achievements made in biomedicine and the f ield of psychology mean that we no longer need to worry about things like deadly diseases or masturbation as a form of insanity. For better or worse, we have developed more effective ways to gather information, treat skin abnormalities, and even kill each other. But what we are not constantly reminded of are the human lives that have been damaged or lost in the name of this progress. The following is a list of the 30 most disturbing human experiments in history.

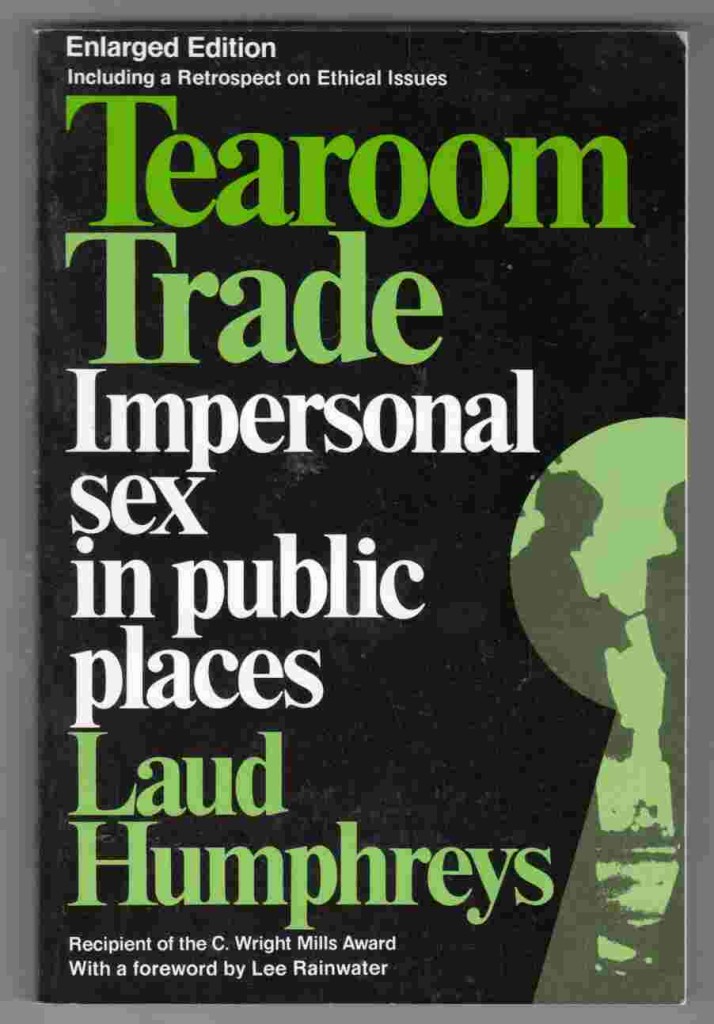

30. The Tearoom Sex Study

Image Source Sociologist Laud Humphreys often wondered about the men who commit impersonal sexual acts with one another in public restrooms. He wondered why “tearoom sex” — fellatio in public restrooms — led to the majority of homosexual arrests in the United States. Humphreys decided to become a “watchqueen” (the person who keeps watch and coughs when a cop or stranger get near) for his Ph.D. dissertation at Washington University. Throughout his research, Humphreys observed hundreds of acts of fellatio and interviewed many of the participants. He found that 54% of his subjects were married, and 38% were very clearly neither bisexual or homosexual. Humphreys’ research shattered a number of stereotypes held by both the public and law enforcement.

29. Prison Inmates as Test Subjects

Image Source In 1951, Dr. Albert M. Kligman, a dermatologist at the University of Pennsylvania and future inventor of Retin-A, began experimenting on inmates at Philadelphia’s Holmesburg Prison. As Kligman later told a newspaper reporter, “All I saw before me were acres of skin. It was like a farmer seeing a field for the first time.” Over the next 20 years, inmates willingly allowed Kligman to use their bodies in experiments involving toothpaste, deodorant, shampoo, skin creams, detergents, liquid diets, eye drops, foot powders, and hair dyes. Though the tests required constant biopsies and painful procedures, none of the inmates experienced long-term harm.

28. Henrietta Lacks

Image Source In 1955, Henrietta Lacks, a poor, uneducated African-American woman from Baltimore, was the unwitting source of cells which where then cultured for the purpose of medical research. Though researchers had tried to grow cells before, Henrietta’s were the first successfully kept alive and cloned. Henrietta’s cells, known as HeLa cells, have been instrumental in the development of the polio vaccine, cancer research, AIDS research, gene mapping, and countless other scientific endeavors. Henrietta died penniless and was buried without a tombstone in a family cemetery. For decades, her husband and five children were left in the dark about their wife and mother’s amazing contribution to modern medicine.

27. Project QKHILLTOP

Image Source In 1954, the CIA developed an experiment called Project QKHILLTOP to study Chinese brainwashing techniques, which they then used to develop new methods of interrogation. Leading the research was Dr. Harold Wolff of Cornell University Medical School. After requesting that the CIA provide him with information on imprisonment, deprivation, humiliation, torture, brainwashing, hypnoses, and more, Wolff’s research team began to formulate a plan through which they would develop secret drugs and various brain damaging procedures. According to a letter he wrote, in order to fully test the effects of the harmful research, Wolff expected the CIA to “make available suitable subjects.”

26. Stateville Penitentiary Malaria Study

Image Source During World War II, malaria and other tropical diseases were impeding the efforts of American military in the Pacific. In order to get a grip, the Malaria Research Project was established at Stateville Penitentiary in Joliet, Illinois. Doctors from the University of Chicago exposed 441 volunteer inmates to bites from malaria-infected mosquitos. Though one inmate died of a heart attack, researchers insisted his death was unrelated to the study. The widely-praised experiment continued at Stateville for 29 years, and included the first human test of Primaquine, a medication still used in the treatment of malaria and Pneumocystis pneumonia.

25. Emma Eckstein and Sigmund Freud

Image Source Despite seeking the help of Sigmund Freud for vague symptoms like stomach ailments and slight depression, 27-year old Emma Eckstein was “treated” by the German doctor for hysteria and excessive masturbation, a habit then considered dangerous to mental health. Emma’s treatment included a disturbing experimental surgery in which she was anesthetized with only a local anesthetic and cocaine before the inside of her nose was cauterized. Not surprisingly, Emma’s surgery was a disaster. Whether Emma was a legitimate medical patient or a source of more amorous interest for Freud, as a recent movie suggests, Freud continued to treat Emma for three years.

24. Dr. William Beaumont and the Stomach

Image Source In 1822, a fur trader on Mackinac Island in Michigan was accidentally shot in the stomach and treated by Dr. William Beaumont. Despite dire predictions, the fur trader survived — but with a hole (fistula) in his stomach that never healed. Recognizing the unique opportunity to observe the digestive process, Beaumont began conducting experiments. Beaumont would tie food to a string, then insert it through the hole in the trader’s stomach. Every few hours, Beaumont would remove the food to observe how it had been digested. Though gruesome, Beaumont’s experiments led to the worldwide acceptance that digestion was a chemical, not a mechanical, process.

23. Electroshock Therapy on Children

Image Source In the 1960s, Dr. Lauretta Bender of New York’s Creedmoor Hospital began what she believed to be a revolutionary treatment for children with social issues — electroshock therapy. Bender’s methods included interviewing and analyzing a sensitive child in front of a large group, then applying a gentle amount of pressure to the child’s head. Supposedly, any child who moved with the pressure was showing early signs of schizophrenia. Herself the victim of a misunderstood childhood, Bender was said to be unsympathetic to the children in her care. By the time her treatments were shut down, Bender had used electroshock therapy on over 100 children, the youngest of whom was age three.

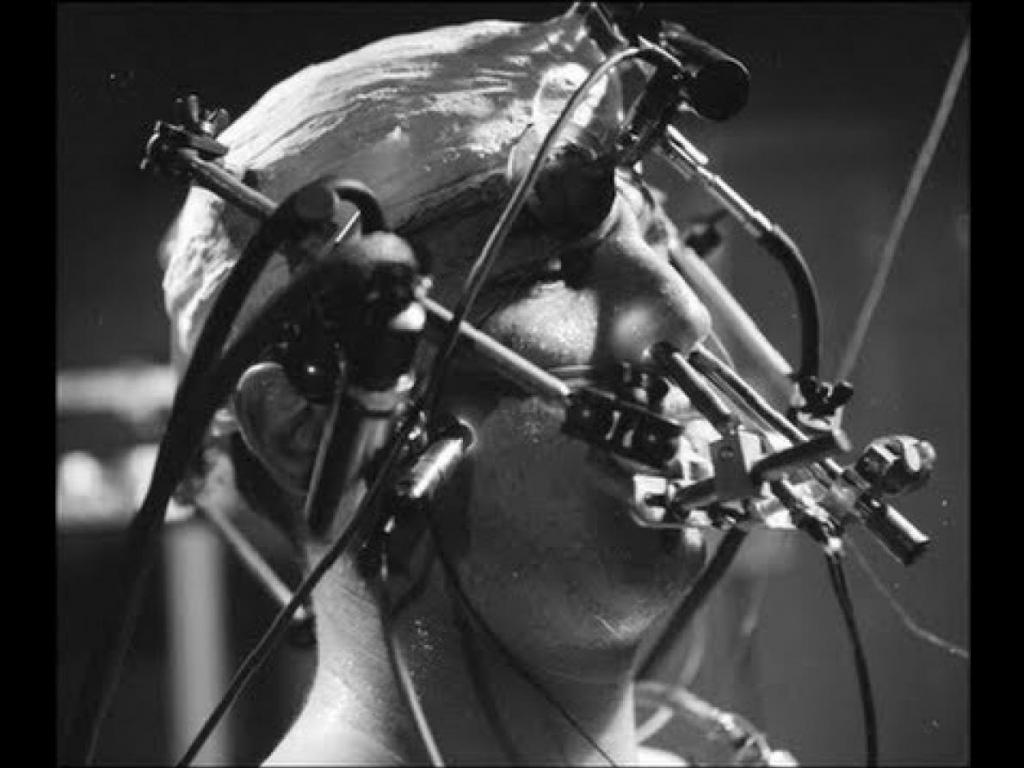

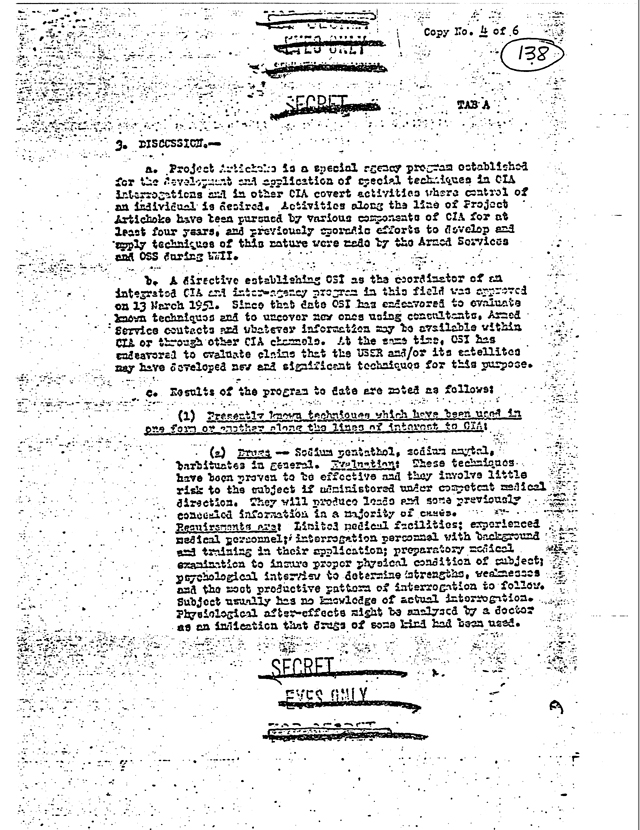

22. Project Artichoke

Image Source In the 1950s, the CIA’s Office of Scientific Intelligence ran a series of mind control projects in an attempt to answer the question “Can we get control of an individual to the point where he will do our bidding against his will and even against fundamental laws of nature?” One of these programs, Project Artichoke, studied hypnosis, forced morphine addiction, drug withdrawal, and the use of chemicals to incite amnesia in unwitting human subjects. Though the project was eventually shut down in the mid-1960s, the project opened the door to extensive research on the use of mind-control in field operations.

21. Hepatitis in Mentally Disabled Children

Image Source In the 1950s, Willowbrook State School, a New York state-run institution for mentally handicapped children, began experiencing outbreaks of hepatitis. Due to unsanitary conditions, it was virtually inevitable that these children would contract hepatitis. Dr. Saul Krugman, sent to investigate the outbreak, proposed an experiment that would assist in developing a vaccine. However, the experiment required deliberately infecting children with the disease. Though Krugman’s study was controversial from the start, critics were eventually silenced by the permission letters obtained from each child’s parents. In reality, offering one’s child to the experiment was oftentimes the only way to guarantee admittance into the overcrowded institution.

20. Operation Midnight Climax

Image Source Initially established in the 1950s as a sub-project of a CIA-sponsored, mind-control research program, Operation Midnight Climax sought to study the effects of LSD on individuals. In San Francisco and New York, unconsenting subjects were lured to safehouses by prostitutes on the CIA payroll, unknowingly given LSD and other mind-altering substances, and monitored from behind one-way glass. Though the safehouses were shut down in 1965, when it was discovered that the CIA was administering LSD to human subjects, Operation Midnight Climax was a theater for extensive research on sexual blackmail, surveillance technology, and the use of mind-altering drugs on field operations.

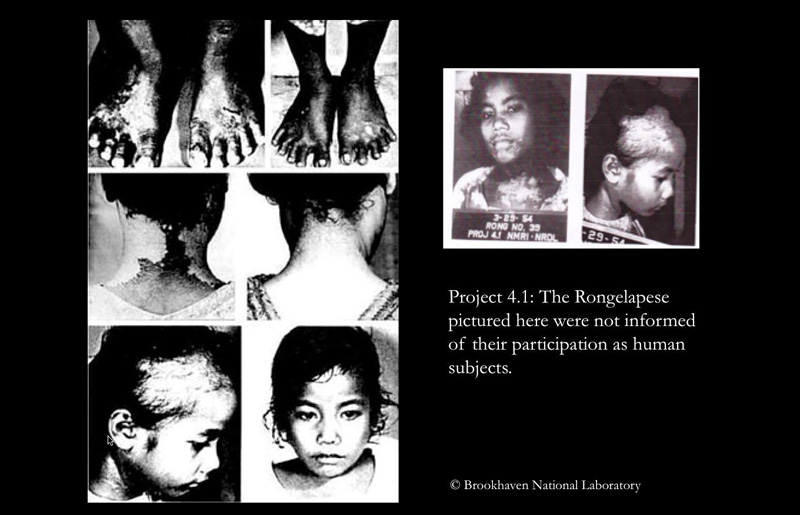

19. Study of Humans Accidentally Exposed to Fallout Radiation

Image Source The 1954 “Study of Response of Human Beings exposed to Significant Beta and Gamma Radiation due to Fall-out from High-Yield Weapons,” known better as Project 4.1, was a medical study conducted by the U.S. of residents of the Marshall Islands. When the Castle Bravo nuclear test resulted in a yield larger than originally expected, the government instituted a top secret study to “evaluate the severity of radiation injury” to those accidentally exposed. Though most sources agree the exposure was unintentional, many Marshallese believed Project 4.1 was planned before the Castle Bravo test. In all, 239 Marshallese were exposed to significant levels of radiation.

18. The Monster Study

Image Source In 1939, University of Iowa researchers Wendell Johnson and Mary Tudor conducted a stuttering experiment on 22 orphan children in Davenport, Iowa. The children were separated into two groups, the first of which received positive speech therapy where children were praised for speech fluency. In the second group, children received negative speech therapy and were belittled for every speech imperfection. Normal-speaking children in the second group developed speech problems which they then retained for the rest of their lives. Terrified by the news of human experiments conducted by the Nazis, Johnson and Tudor never published the results of their “Monster Study.”

17. Project MKUltra

Image Source Project MKUltra is the code name of a CIA-sponsored research operation that experimented in human behavioral engineering. From 1953 to 1973, the program employed various methodologies to manipulate the mental states of American and Canadian citizens. These unwitting human test subjects were plied with LSD and other mind-altering drugs, hypnosis, sensory deprivation, isolation, verbal and sexual abuse, and various forms of torture. Research occurred at universities, hospitals, prisons, and pharmaceutical companies. Though the project sought to develop “chemical […] materials capable of employment in clandestine operations,” Project MKUltra was ended by a Congress-commissioned investigation into CIA activities within the U.S.

16. Experiments on Newborns

Image Source In the 1960s, researchers at the University of California began an experiment to study changes in blood pressure and blood flow. The researchers used 113 newborns ranging in age from one hour to three days old as test subjects. In one experiment, a catheter was inserted through the umbilical arteries and into the aorta. The newborn’s feet were then immersed in ice water for the purpose of testing aortic pressure. In another experiment, up to 50 newborns were individually strapped onto a circumcision board, then tilted so that their blood rushed to their head and their blood pressure could be monitored.

15. The Aversion Project

Image Source In 1969, during South Africa’s detestable Apartheid era, thousands of homosexuals were handed over to the care of Dr. Aubrey Levin, an army colonel and psychologist convinced he could “cure” homosexuals. At the Voortrekkerhoogte military hospital near Pretoria, Levin used electroconvulsive aversion therapy to “reorientate” his patients. Electrodes were strapped to a patient’s upper arm with wires running to a dial calibrated from 1 to 10. Homosexual men were shown pictures of a naked man and encouraged to fantasize, at which point the patient was subjected to severe shocks. When Levin was warned that he would be named an abuser of human rights, he emigrated to Canada where he currently works at a teaching hospital.

14. Medical Experiments on Prison Inmates

Image Source Perhaps one benefit of being an inmate at California’s San Quentin prison is the easy access to acclaimed Bay Area doctors. But if that’s the case, then a downside is that these doctors also have easy access to inmates. From 1913 to 1951, Dr. Leo Stanley, chief surgeon at San Quentin, used prisoners as test subjects in a variety of bizarre medical experiments. Stanley’s experiments included sterilization and potential treatments for the Spanish Flu. In one particularly disturbing experiment, Stanley performed testicle transplants on living prisoners using testicles from executed prisoners and, in some cases, from goats and boars.

13. Sexual Reassignment

Image Source In 1965, Canadian David Peter Reimer was born biologically male. But at seven months old, his penis was accidentally destroyed during an unconventional circumcision by cauterization. John Money, a psychologist and proponent of the idea that gender is learned, convinced the Reimers that their son would be more likely to achieve a successful, functional sexual maturation as a girl. Though Money continued to report only success over the years, David’s own account insisted that he had never identified as female. He spent his childhood teased, ostracized, and seriously depressed. At age 38, David committed suicide by shooting himself in the head.

12. Effect of Radiation on Testicles

Image Source Between 1963 and 1973, dozens of Washington and Oregon prison inmates were used as test subjects in an experiment designed to test the effects of radiation on testicles. Bribed with cash and the suggestion of parole, 130 inmates willingly agreed to participate in the experiments conducted by the University of Washington on behalf of the U.S. government. In most cases, subjects were zapped with over 400 rads of radiation (the equivalent of 2,400 chest x-rays) in 10 minute intervals. However, it was much later that the inmates learned the experiments were far more dangerous than they had been told. In 2000, the former participants settled a $2.4 million class-action settlement from the University.

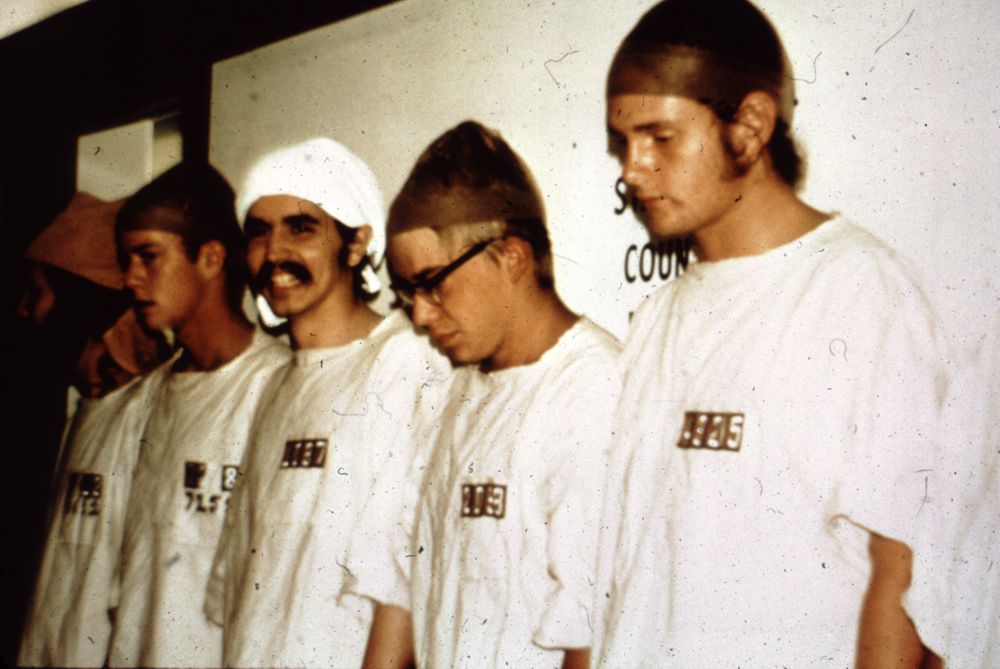

11. Stanford Prison Experiment

Image Source Conducted at Stanford University from August 14-20, 1971, the Stanford Prison Experiment was an investigation into the causes of conflict between military guards and prisoners. Twenty-four male students were chosen and randomly assigned roles of prisoners and guards. They were then situated in a specially-designed mock prison in the basement of the Stanford psychology building. Those subjects assigned to be guards enforced authoritarian measures and subjected the prisoners to psychological torture. Surprisingly, many of the prisoners accepted the abuses. Though the experiment exceeded the expectations of all of the researchers, it was abruptly ended after only six days.

10. Syphilis Experiments in Guatemala

Image Source From 1946 to 1948, the United States government, Guatemalan president Juan José Arévalo, and some Guatemalan health ministries, cooperated in a disturbing human experiment on unwitting Guatemalan citizens. Doctors deliberately infected soldiers, prostitutes, prisoners, and mental patients with syphilis and other sexually transmitted diseases in an attempt to track their untreated natural progression. Treated only with antibiotics, the experiment resulted in at least 30 documented deaths. In 2010, the United States made a formal apology to Guatemala for their involvement in these experiments.

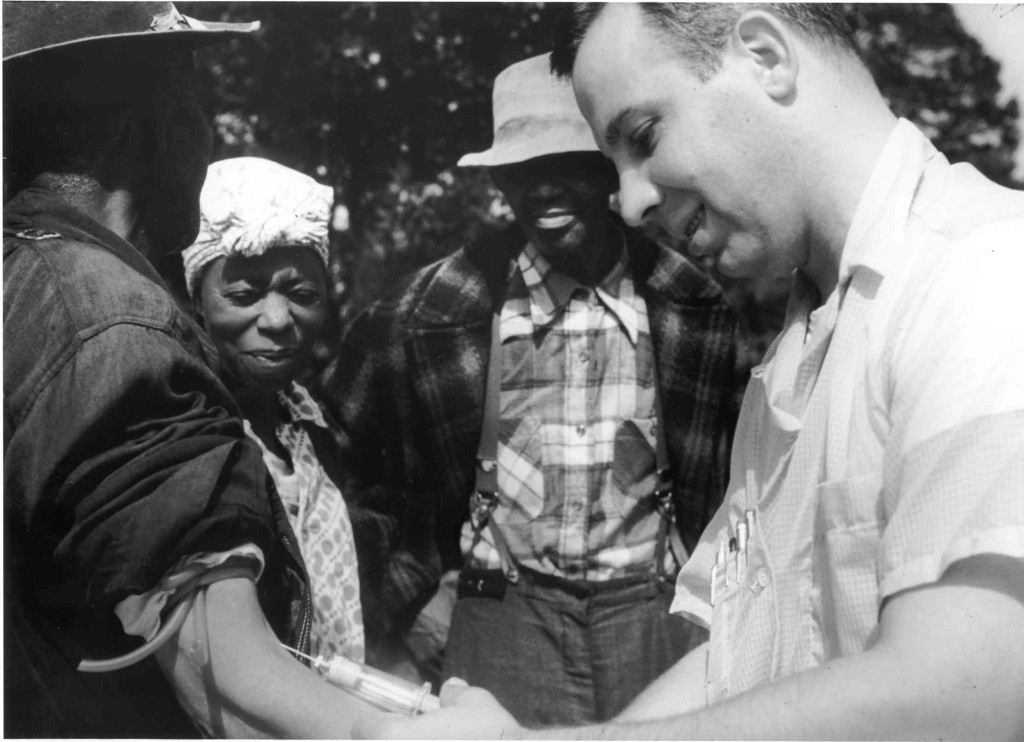

9. Tuskegee Syphilis Study

Image Source In 1932, the U.S. Public Health Service began working with the Tuskegee Institute to track the natural progression of untreated syphilis. Six hundred poor, illiterate, male sharecroppers were found and hired in Macon County, Alabama. Of the 600 men, only 399 had previously contracted syphilis, and none were told they had a life threatening disease. Instead, they were told they were receiving free healthcare, meals, and burial insurance in exchange for participating. Even after Penicillin was proven an effective cure for syphilis in 1947, the study continued until 1972. In addition to the original subjects, victims of the study included wives who contracted the disease, and children born with congenital syphilis. In 1997, President Bill Clinton formally apologized to those affected by what is often called the “most infamous biomedical experiment in U.S. history.”

8. Milgram Experiment

In 1961, Stanley Milgram, a psychologist at Yale University, began a series of social psychology experiments that measured the willingness of test subjects to obey an authority figure. Conducted only three months after the start of the trial of German Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann, Milgram’s experiment sought to answer the question, “Could it be that Eichmann and his million accomplices in the Holocaust were just following orders?” In the experiment, two participants (one secretly an actor and one an unwitting test subject) were separated into two rooms where they could hear, but not see, each other. The test subject would then read a series of questions to the actor, punishing each wrong answer with an electric shock. Though many people would indicate their desire to stop the experiment, almost all subjects continued when they were told they would not be held responsible, or that there would not be any permanent damage.

7. Infected Mosquitos in Towns

In 1956 and 1957, the United States Army conducted a number of biological warfare experiments on the cities of Savannah, Georgia and Avon Park, Florida. In one such experiment, millions of infected mosquitos were released into the two cities, in order to see if the insects could spread yellow fever and dengue fever. Not surprisingly, hundreds of researchers contracted illnesses that included fevers, respiratory problems, stillbirths, encephalitis, and typhoid. In order to photograph the results of their experiments, Army researchers pretended to be public health workers. Several people died as a result of the research.

6. Human Experimentation in the Soviet Union

Beginning in 1921 and continuing for most of the 21st century, the Soviet Union employed poison laboratories known as Laboratory 1, Laboratory 12, and Kamera as covert research facilities of the secret police agencies. Prisoners from the Gulags were exposed to a number of deadly poisons, the purpose of which was to find a tasteless, odorless chemical that could not be detected post mortem. Tested poisons included mustard gas, ricin, digitoxin, and curare, among others. Men and women of varying ages and physical conditions were brought to the laboratories and given the poisons as “medication,” or part of a meal or drink.

5. Human Experimentation in North Korea

Image Source Several North Korean defectors have described witnessing disturbing cases of human experimentation. In one alleged experiment, 50 healthy women prisoners were given poisoned cabbage leaves — all 50 women were dead within 20 minutes. Other described experiments include the practice of surgery on prisoners without anesthesia, purposeful starvation, beating prisoners over the head before using the zombie-like victims for target practice, and chambers in which whole families are murdered with suffocation gas. It is said that each month, a black van known as “the crow” collects 40-50 people from a camp and takes them to an known location for experiments.

4. Nazi Human Experimentation

Image Source Over the course of the Third Reich and the Holocaust, Nazi Germany conducted a series of medical experiments on Jews, POWs, Romani, and other persecuted groups. The experiments were conducted in concentration camps, and in most cases resulted in death, disfigurement, or permanent disability. Especially disturbing experiments included attempts to genetically manipulate twins; bone, muscle, and nerve transplantation; exposure to diseases and chemical gasses; sterilization, and anything else the infamous Nazi doctors could think up. After the war, these crimes were tried as part of the Nuremberg Trial and ultimately led to the development of the Nuremberg Code of medical ethics.

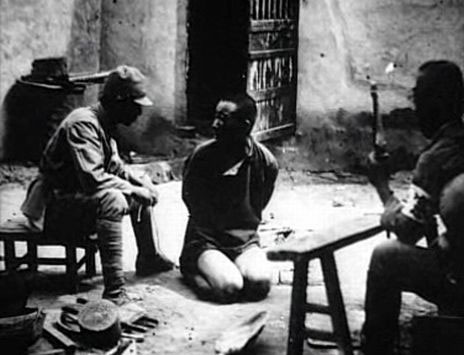

3. Unit 731

Image Source From 1937 to 1945, the imperial Japanese Army developed a covert biological and chemical warfare research experiment called Unit 731. Based in the large city of Harbin, Unit 731 was responsible for some of the most atrocious war crimes in history. Chinese and Russian subjects — men, women, children, infants, the elderly, and pregnant women — were subjected to experiments which included the removal of organs from a live body, amputation for the study of blood loss, germ warfare attacks, and weapons testing. Some prisoners even had their stomachs surgically removed and their esophagus reattached to the intestines. Many of the scientists involved in Unit 731 rose to prominent careers in politics, academia, business, and medicine.

2. Radioactive Materials in Pregnant Women

Image Source Shortly after World War II, with the impending Cold War forefront on the minds of Americans, many medical researchers were preoccupied with the idea of radioactivity and chemical warfare. In an experiment at Vanderbilt University, 829 pregnant women were given “vitamin drinks” they were told would improve the health of their unborn babies. Instead, the drinks contained radioactive iron and the researchers were studying how quickly the radioisotope crossed into the placenta. At least seven of the babies later died from cancers and leukemia, and the women themselves experienced rashes, bruises, anemia, loss of hair and tooth, and cancer.

1. Mustard Gas Tested on American Military

Image Source In 1943, the U.S. Navy exposed its own sailors to mustard gas. Officially, the Navy was testing the effectiveness of new clothing and gas masks against the deadly gas that had proven so terrifying in the first World War. The worst of the experiments occurred at the Naval Research Laboratory in Washington. Seventeen and 18-year old boys were approached after eight weeks of boot camp and asked if they wanted to participate in an experiment that would help shorten the war. Only when the boys reached the Research Laboratory were they told the experiment involved mustard gas. The participants, almost all of whom suffered severe external and internal burns, were ignored by the Navy and, in some cases, threatened with the Espionage Act. In 1991, the reports were finally declassified and taken before Congress.

28. Prison Inmates as Test Subjects Henrietta Lacks 26. Project QKHILLTOP 25. Stateville Penitentiary Malaria Study Stateville Penitentiary Malaria Study: Primaquine 24. Emma Eckstein 23. Dr. William Beaumont Dr. William Beaumont 21. Electroshock Therapy on Children 21. Project Artichoke 20. Operation Midnight Climax 19. Study of Humans Accidentally Exposed to Fallout Radiation 18. The Monster Experiment 17. Project MKUltra 16. Experiments on Newborns 15. The Aversion Project 14. Medical Experiments on Prison Inmates 13. Sexual Reassignment 12. Effect of Radiation on Testicles 11. Stanford Prison Experiment 10. Syphilis Experiment in Guatemala 9. Tuskegee Syphilis Study 8. Milgram Experiment 7. Infected Mosquitos in Towns 6. Human Experimentation in the Soviet Union 5. Human Experimentation in North Korea 4. Nazi Human Experimentation 3. Unit 731 2. Radioactive Materials in Pregnant Women 1. Mustard Gas Tested on American Military

- Psychology Education

- Bachelors in Psychology

- Masters in Psychology

- Doctorate in Psychology

- Psychology Resources

- Psychology License

- Psychology Salary

- Psychology Career

- Psychology Major

- What is Psychology

- Up & Coming Programs

- Top 10 Up and Coming Undergraduate Psychology Programs in the South

- Top 10 Up and Coming Undergraduate Psychology Programs in the Midwest

- Top 10 Up and Coming Undergraduate Psychology Programs in the West

- Top 10 Up and Coming Undergraduate Psychology Programs in the East

- Best Psychology Degrees Scholarship Opportunity

- The Pursuit of Excellence in Psychology Scholarship is Now Closed

- Meet Gemma: Our First Psychology Scholarship Winner

- 50 Most Affordable Clinical Psychology Graduate Programs

- 50 Most Affordable Selective Small Colleges for a Psychology Degree

- The 50 Best Schools for Psychology: Undergraduate Edition

- 30 Great Small Colleges for a Counseling Degree (Bachelor’s)

- Top 10 Best Online Bachelors in Psychology Degree Programs

- Top 10 Online Child Psychology Degree Programs

- 10 Best Online Forensic Psychology Degree Programs

- Top 10 Online Master’s in Psychology Degree Programs

- Top 15 Most Affordable School Psychology Programs

- Top 20 Most Innovative Graduate Psychology Degree Programs

- Top 8 Online Sports Psychology Degree Programs

- Recent Posts

- Does Psychology Require Math? – Requirements for Psychology Majors

- 10 Classes You Will Take as a Psychology Major

- Top 15 Highest-Paying Jobs with a Master’s Degree in Psychology

- The Highest Paying Jobs with an Associate’s Degree in Psychology

- The Highest-Paying Jobs with a Bachelor’s in Psychology

- Should I Major in Psychology?

- How to Become a CBT Therapist

- What is a Social Psychologist?

- How to Become a Clinical Neuropsychologist

- MA vs. MS in Psychology: What’s the Difference?

- PsyD vs. PhD in Psychology: What’s the Difference?

- What Can You Do with a Master’s in Psychology?

- What Can You Do With A PhD in Psychology?

- Master’s in Child Psychology Guide

- Master’s in Counseling Psychology – A Beginner’s Guide

- Master’s in Forensic Psychology – A Beginner’s Guide

- 8 Reasons to Become a Marriage and Family Therapist

- What Do Domestic Violence & Abuse Counselors Do?

- What Training is Needed to Be a Psychologist for People of the LGBTQ Community?

- 15 Inspiring TED Talks on Intelligence and Critical Thinking

- The 30 Most Inspiring Personal Growth and Development Blogs

- 30 Most Prominent Psychologists on Twitter

- New Theory Discredits the Myth that Individuals with Asperger’s Syndrome Lack Empathy

- 10 Crazy Things Famous People Have Believed

- Psychology Infographics

- Top Infographics About Psychology

- The Birth Order Effect [Infographic]

- The Psychology of Dogs [Infographic]

- Can Going Green Improve Your Mental Health? [Infographic]

- Surprising Alternative Treatments for Mental Disorders [Infographic]

- What Can Humans Learn From Animals? [Infographic]

10 Psychological Experiments That Could Never Happen Today

Nowadays, the American Psychological Association has a Code of Conduct in place when it comes to ethics in psychological experiments. Experimenters must adhere to various rules pertaining to everything from confidentiality to consent to overall beneficence. Review boards are in place to enforce these ethics. But the standards were not always so strict, which is how some of the most famous studies in psychology came about.

1. The Little Albert Experiment

At Johns Hopkins University in 1920, John B. Watson conducted a study of classical conditioning, a phenomenon that pairs a conditioned stimulus with an unconditioned stimulus until they produce the same result. This type of conditioning can create a response in a person or animal towards an object or sound that was previously neutral. Classical conditioning is commonly associated with Ivan Pavlov, who rang a bell every time he fed his dog until the mere sound of the bell caused his dog to salivate.

Watson tested classical conditioning on a 9-month-old baby he called Albert B. The young boy started the experiment loving animals, particularly a white rat. Watson started pairing the presence of the rat with the loud sound of a hammer hitting metal. Albert began to develop a fear of the white rat as well as most animals and furry objects. The experiment is considered particularly unethical today because Albert was never desensitized to the phobias that Watson produced in him. (The child died of an unrelated illness at age 6, so doctors were unable to determine if his phobias would have lasted into adulthood.)

2. Asch Conformity Experiments

Solomon Asch tested conformity at Swarthmore College in 1951 by putting a participant in a group of people whose task was to match line lengths. Each individual was expected to announce which of three lines was the closest in length to a reference line. But the participant was placed in a group of actors, who were all told to give the correct answer twice then switch to each saying the same incorrect answer. Asch wanted to see whether the participant would conform and start to give the wrong answer as well, knowing that he would otherwise be a single outlier.

Thirty-seven of the 50 participants agreed with the incorrect group despite physical evidence to the contrary. Asch used deception in his experiment without getting informed consent from his participants, so his study could not be replicated today.

3. The Bystander Effect

Some psychological experiments that were designed to test the bystander effect are considered unethical by today’s standards. In 1968, John Darley and Bibb Latané developed an interest in crime witnesses who did not take action. They were particularly intrigued by the murder of Kitty Genovese , a young woman whose murder was witnessed by many, but still not prevented.

The pair conducted a study at Columbia University in which they would give a participant a survey and leave him alone in a room to fill out the paper. Harmless smoke would start to seep into the room after a short amount of time. The study showed that the solo participant was much faster to report the smoke than participants who had the exact same experience, but were in a group.

The studies became progressively unethical by putting participants at risk of psychological harm. Darley and Latané played a recording of an actor pretending to have a seizure in the headphones of a person, who believed he or she was listening to an actual medical emergency that was taking place down the hall. Again, participants were much quicker to react when they thought they were the sole person who could hear the seizure.

4. The Milgram Experiment

Yale psychologist Stanley Milgram hoped to further understand how so many people came to participate in the cruel acts of the Holocaust. He theorized that people are generally inclined to obey authority figures, posing the question , “Could it be that Eichmann and his million accomplices in the Holocaust were just following orders? Could we call them all accomplices?” In 1961, he began to conduct experiments of obedience.

Participants were under the impression that they were part of a study of memory . Each trial had a pair divided into “teacher” and “learner,” but one person was an actor, so only one was a true participant. The drawing was rigged so that the participant always took the role of “teacher.” The two were moved into separate rooms and the “teacher” was given instructions. He or she pressed a button to shock the “learner” each time an incorrect answer was provided. These shocks would increase in voltage each time. Eventually, the actor would start to complain followed by more and more desperate screaming. Milgram learned that the majority of participants followed orders to continue delivering shocks despite the clear discomfort of the “learner.”

Had the shocks existed and been at the voltage they were labeled, the majority would have actually killed the “learner” in the next room. Having this fact revealed to the participant after the study concluded would be a clear example of psychological harm.

5. Harlow’s Monkey Experiments

In the 1950s, Harry Harlow of the University of Wisconsin tested infant dependency using rhesus monkeys in his experiments rather than human babies. The monkey was removed from its actual mother which was replaced with two “mothers,” one made of cloth and one made of wire. The cloth “mother” served no purpose other than its comforting feel whereas the wire “mother” fed the monkey through a bottle. The monkey spent the majority of his day next to the cloth “mother” and only around one hour a day next to the wire “mother,” despite the association between the wire model and food.

Harlow also used intimidation to prove that the monkey found the cloth “mother” to be superior. He would scare the infants and watch as the monkey ran towards the cloth model. Harlow also conducted experiments which isolated monkeys from other monkeys in order to show that those who did not learn to be part of the group at a young age were unable to assimilate and mate when they got older. Harlow’s experiments ceased in 1985 due to APA rules against the mistreatment of animals as well as humans . However, Department of Psychiatry Chair Ned H. Kalin, M.D. of the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health has recently begun similar experiments that involve isolating infant monkeys and exposing them to frightening stimuli. He hopes to discover data on human anxiety, but is meeting with resistance from animal welfare organizations and the general public.

6. Learned Helplessness

The ethics of Martin Seligman’s experiments on learned helplessness would also be called into question today due to his mistreatment of animals. In 1965, Seligman and his team used dogs as subjects to test how one might perceive control. The group would place a dog on one side of a box that was divided in half by a low barrier. Then they would administer a shock, which was avoidable if the dog jumped over the barrier to the other half. Dogs quickly learned how to prevent themselves from being shocked.

Seligman’s group then harnessed a group of dogs and randomly administered shocks, which were completely unavoidable. The next day, these dogs were placed in the box with the barrier. Despite new circumstances that would have allowed them to escape the painful shocks, these dogs did not even try to jump over the barrier; they only cried and did not jump at all, demonstrating learned helplessness.

7. Robbers Cave Experiment

Muzafer Sherif conducted the Robbers Cave Experiment in the summer of 1954, testing group dynamics in the face of conflict. A group of preteen boys were brought to a summer camp, but they did not know that the counselors were actually psychological researchers. The boys were split into two groups, which were kept very separate. The groups only came into contact with each other when they were competing in sporting events or other activities.

The experimenters orchestrated increased tension between the two groups, particularly by keeping competitions close in points. Then, Sherif created problems, such as a water shortage, that would require both teams to unite and work together in order to achieve a goal. After a few of these, the groups became completely undivided and amicable.

Though the experiment seems simple and perhaps harmless, it would still be considered unethical today because Sherif used deception as the boys did not know they were participating in a psychological experiment. Sherif also did not have informed consent from participants.

8. The Monster Study

At the University of Iowa in 1939, Wendell Johnson and his team hoped to discover the cause of stuttering by attempting to turn orphans into stutterers. There were 22 young subjects, 12 of whom were non-stutterers. Half of the group experienced positive teaching whereas the other group dealt with negative reinforcement. The teachers continually told the latter group that they had stutters. No one in either group became stutterers at the end of the experiment, but those who received negative treatment did develop many of the self-esteem problems that stutterers often show. Perhaps Johnson’s interest in this phenomenon had to do with his own stutter as a child , but this study would never pass with a contemporary review board.

Johnson’s reputation as an unethical psychologist has not caused the University of Iowa to remove his name from its Speech and Hearing Clinic .

9. Blue Eyed versus Brown Eyed Students

Jane Elliott was not a psychologist, but she developed one of the most famously controversial exercises in 1968 by dividing students into a blue-eyed group and a brown-eyed group. Elliott was an elementary school teacher in Iowa, who was trying to give her students hands-on experience with discrimination the day after Martin Luther King Jr. was shot, but this exercise still has significance to psychology today. The famous exercise even transformed Elliott’s career into one centered around diversity training.

After dividing the class into groups, Elliott would cite phony scientific research claiming that one group was superior to the other. Throughout the day, the group would be treated as such. Elliott learned that it only took a day for the “superior” group to turn crueler and the “inferior” group to become more insecure. The blue eyed and brown eyed groups then switched so that all students endured the same prejudices.

Elliott’s exercise (which she repeated in 1969 and 1970) received plenty of public backlash, which is probably why it would not be replicated in a psychological experiment or classroom today. The main ethical concerns would be with deception and consent, though some of the original participants still regard the experiment as life-changing .

10. The Stanford Prison Experiment

In 1971, Philip Zimbardo of Stanford University conducted his famous prison experiment, which aimed to examine group behavior and the importance of roles. Zimbardo and his team picked a group of 24 male college students who were considered “healthy,” both physically and psychologically. The men had signed up to participate in a “ psychological study of prison life ,” which would pay them $15 per day. Half were randomly assigned to be prisoners and the other half were assigned to be prison guards. The experiment played out in the basement of the Stanford psychology department where Zimbardo’s team had created a makeshift prison. The experimenters went to great lengths to create a realistic experience for the prisoners, including fake arrests at the participants’ homes.

The prisoners were given a fairly standard introduction to prison life, which included being deloused and assigned an embarrassing uniform. The guards were given vague instructions that they should never be violent with the prisoners, but needed to stay in control. The first day passed without incident, but the prisoners rebelled on the second day by barricading themselves in their cells and ignoring the guards. This behavior shocked the guards and presumably led to the psychological abuse that followed. The guards started separating “good” and “bad” prisoners, and doled out punishments including push ups, solitary confinement, and public humiliation to rebellious prisoners.

Zimbardo explained , “In only a few days, our guards became sadistic and our prisoners became depressed and showed signs of extreme stress.” Two prisoners dropped out of the experiment; one eventually became a psychologist and a consultant for prisons . The experiment was originally supposed to last for two weeks, but it ended early when Zimbardo’s future wife, psychologist Christina Maslach, visited the experiment on the fifth day and told him , “I think it’s terrible what you’re doing to those boys.”

Despite the unethical experiment, Zimbardo is still a working psychologist today. He was even honored by the American Psychological Association with a Gold Medal Award for Life Achievement in the Science of Psychology in 2012 .

Shopping Cart

Articles & Insights

Expand your mind and be inspired with Achology's paradigm-shifting articles. All inspired by the world's greatest minds!

The Dark Side of Psychology: 10 Ethically Dubious Psychology Experiments

By charlotte avery, this article is divided into the following sections:, introduction.

The realm of psychology, with its deep delve into the enigma of the human mind, has been a constant source of intrigue and discovery. Yet, in its quest to unravel the intricacies of human behavior, it has sometimes crossed the lines of ethical conduct. Some experiments, now etched in the annals of psychology, have triggered widespread controversy due to their dubious ethical standards. This article embarks on a journey through ten such psychological experiments that have blurred the lines between scientific pursuit and ethical integrity.

These studies, though significantly contributing to our understanding of human nature, have also sparked intense debates about the moral boundaries within which psychological research should operate. They serve as potent reminders of the delicate balance between the thirst for knowledge and the imperative respect for human rights.

10 Ethically Dubious Psychology Experiments

1. the stanford prison experiment (1971).

One of the most infamous experiments in psychology, the Stanford Prison Experiment was led by psychologist Philip Zimbardo . He recruited college students to play the roles of prisoners and guards in a mock prison. However, the experiment quickly spiraled out of control as the “guards” began to psychologically torment the “prisoners,” leading to severe emotional distress. The study was halted after just six days due to the extreme psychological effects on the participants.

2. The Milgram Experiment (1961)

After the horrors of the Second World War, psychological researchers like Stanley Milgram wondered what made average citizens act like those in Germany who had committed atrocities. Milgram wanted to determine how far people would go carrying out actions that might be detrimental to others if they were ordered or encouraged to do so by an authority figure. The Milgram experiment showed the tension between that obedience to the orders of the authority figure and personal conscience.

In each experiment, Milgram designated three people as either a teacher, learner or experimenter. The “learner” was an actor planted by Milgram and stayed in a room separate from the experimenter and teacher. The teacher attempted to teach the learner how to perform small sets of word associations. When the learner got a pair wrong, the teacher delivered an electric shock to the learner. In reality, there was no shock given. The learner pretended to be in increasingly greater amounts of distress. When some teachers expressed hesitation about increasing the level of shocks, the experimenter encouraged them to do so. Many of the subjects experienced severe psychological distress. The Milgram Conformity Experiment has become the byword for well-intentioned psychological experiments gone wrong.

3. The Little Albert Experiment (1920)

John Watson , the founder of the psychological school of behaviorism, believed that all human behavior was primarily learned. Eager to test his hypothesis, he used an orphan called “Little Albert” as a test subject. He exposed the child to a laboratory rat for several months, which caused no fear response from the boy what-so-ever. Next, at the same time, the child was exposed to the rat, he struck a steel bar with a hammer, scaring the little boy and causing a fear response. By associating the appearance of the rat with the loud noise, Little Albert became afraid of the rat. Naturally, the fear was a condition that needed to be fixed, but the boy left the facility before Watson could remedy things.

4. The Monster Study (1939)

Conducted by Wendell Johnson at the University of Iowa, this study aimed to investigate whether stuttering could be learned. Johnson and his team divided 22 orphan children into two groups – one group received positive speech therapy, praising the fluency of their speech, while the other group received negative speech therapy, criticising every speech imperfection. The latter group developed speech problems, leading to lifelong psychological effects. The experiment earned its nickname “The Monster Study” due to its cruel and unethical methods.

5. Project MK-Ultra (1953-1973)

Project MK-Ultra, also called the CIA mind control program, was a covert operation run by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency from 1953 to 1973. The project aimed to develop mind control techniques that could be used against enemies during the Cold War. It involved several unethical and non-consensual experiments on human subjects, often involving substances like LSD and other chemicals, hypnosis, sensory deprivation, isolation, verbal and sexual abuse.

The objective was to explore various ways to manipulate people’s mental states and alter brain functions, including the potential to extract information from resistant subjects during interrogation or even create programmed assassins. The project was officially sanctioned in 1953, reduced in scope in 1964, further curtailed in 1967, and officially halted in 1973. The information about MK-Ultra came to public light in 1975 through investigations by the Church Committee and the Rockefeller Commission, and the project became a symbol for illegal and unethical government experiments.

6. The Robbers Cave Experiment (1954)

In this study conducted by Muzafer Sherif, 22 twelve-year-old boys were unknowingly pitted against each other in a summer camp setting. The boys were divided into two separate groups, the Rattlers and the Eagles, and encouraged to compete. The competition escalated into serious conflict, demonstrating how easily ordinary individuals can become adversaries due to group conflict. The experiment raised ethical concerns as the participants were intentionally subjected to psychological stress without their knowledge or consent.

7. The Asch Conformity Experiments (1951)

Solomon Asch conducted a series of studies to investigate the degree to which individuals would conform to a group. Participants were asked to match the length of lines. They were seated with actors who intentionally gave incorrect answers. Surprisingly, a significant number of participants also gave incorrect answers in order to conform to the group. While not as harmful as some others on this list, the experiment was ethically dubious as it involved deception.

8. David Reimer Case (1965-2004)

After a botched circumcision, psychologist John Money suggested that David Reimer be raised as a girl, arguing that gender identity was primarily learned. However, despite being raised as a girl, Reimer struggled with his identity and eventually transitioned back to living as a male in his teens. The case is considered one of psychology’s most compassionless ethically dubious experiments due to the lifelong psychological suffering caused to Reimer, who tragically took his own life in 2004.

9. The Aversion Project (1970s-1980s)

During apartheid in South Africa, the military conducted what came to be known as The Aversion Project. Gay soldiers were forced to undergo “aversion therapy” to “cure” them of their homosexuality. This included administering electric shocks while showing the soldiers homosexual pornography. The project is widely criticized for its gross violation of human rights and unethical treatment of individuals based on their sexual orientation.

10. The Third Wave Experiment (1967)

High school teacher Ron Jones conducted this experiment to demonstrate how the German populace could accept the actions of the Nazi regime during the Second World War. He created a movement called “The Third Wave” and implemented strict rules and salutes in his classroom. Within days, the movement spread throughout the school, with students policing each other. The experiment ended after five days when students began to take the movement too seriously. The lack of informed consent and the potential psychological effects on the students raised serious ethical questions.

These experiments, while providing valuable insights into human behavior, underscore the necessity of ethical guidelines in psychological research. They serve as reminders of the potential harm that can occur when the pursuit of knowledge outweighs the respect for human dignity and rights.

The Ethical Paradoxes in Psychology’s Past

Reflecting on these 10 ethically dubious psychological experiments, we are confronted with a paradox. Each study, despite its ethical shortcomings, has contributed significantly to our understanding of human behavior and thought. They have provided valuable insights into conformity, obedience, group dynamics, and even the nature of evil. Yet, the cost at which these insights were obtained is profoundly unsettling.

These experiments serve as stark reminders of the potential for harm when the pursuit of knowledge supersedes the respect for human dignity and rights. They underscore the vital importance of ethical oversight in research, ensuring that the quest for understanding never compromises the wellbeing of individuals involved.

In scrutinising these studies, we do not merely expose psychology’s darker past but also illuminate the path forward. They act as cautionary tales, guiding current and future researchers to conduct their work with the utmost regard for ethics. As we continue to delve into the mysteries of the human mind , let these experiments serve as our moral compass, reminding us that the ends do not always justify the means, especially when it comes to the sanctity of human life.

Browse Achology Quotes:

► Book Recommendation of the Month

The ultimate life coaching handbook by kain ramsay.

A Comprehensive Guide to the Methodology, Principles and practice of Life Coaching

Misconceptions and industry shortcomings make life coaching frequently misunderstood, as many so-called coaches fail to achieve real results. The lack of wise guidance further fuels this widespread skepticism and distrust.

Get updates from the Academy of Modern Applied Psychology

About Achology

Useful links, our policies, our 7 schools, connect with us, © 2024 achology.

There was a problem reporting this post.

Block Member?

Please confirm you want to block this member.

You will no longer be able to:

- Mention this member in posts

Please allow a few minutes for this process to complete.

We've updated our Privacy Policy to make it clearer how we use your personal data. We use cookies to provide you with a better experience. You can read our Cookie Policy here.

Neuroscience News & Research

Stay up to date on the topics that matter to you

Three Psychology Experiments That Pushed the Limit of Ethics

Complete the form below to unlock access to ALL audio articles.

Last month, a team of volunteers emerged from 40 days of isolation in the Lombrives cave in south-west France. This ordeal was part of a scientific study called the Deep Time experiment. The volunteers were tasked with going without sunlight, phones or clocks for the duration of the experiment. The study aimed to understand how the human brain would be affected as it lost its grasp on time and space. Putting human subjects, even volunteers, through this might seem ethically dubious, but pales in comparison to the questions raised by these three studies.

The ultimate isolation: Hebb’s “pathological boredom”

In 2008, the BBC attempted to re-enact Hebb's experiments. Credit: BBC Horizon

Hebb and his team wanted to see how this environment, one that wasn’t entirely devoid of sensory information, but that was incredibly monotonous and boring, would affect the volunteers. Initially, the participants, who were all university students, thought about their results, or the papers they had due. But after a while, their minds instead drifted onto memories from their childhood. Eventually, most of the participants reported that they became unable to think about anything for any length of time. These details were reported by Hebb’s collaborator Woodburn Heron in an article published in Scientific American . The subjects also showed impaired mental performance, registering lower results on tests of mental arithmetic and word association. Most strikingly of all, the subjects reported that, despite their complete absence of sensory stimulation, they experienced an array of hallucinations, including one participant who saw endless images of babies. These hallucinations, which Heron compared to the effects of the hallucinogenic drug mescaline, grew in complexity over time – one participant eventually reported “a procession of squirrels with sacks over their shoulders marching ‘purposefully’across the visual field.” The hallucinations were accompanied by sounds and even sensations across the volunteers’ bodies. Summing up these weird and distressing effects, Heron concluded that “a changing sensory environment seems essential for human beings.”

How malleable is our willpower?

The facebook study: how contagious are emotions.

Credit: Pixabay

This study started huge controversy when it was ascertained that the only consent Facebook sought was signing up for the platform. Facebook's Data Use Policy, the company said, gave them all the permission they needed to play around with users’ feeds. Whilst these findings were interesting, the ethically dubious way in which the study was conducted makes for uncomfortable reading. The ethical quandaries involved, and the reasons why the study was able to bypass certain regulations, were summed up by bioethicist Michelle N. Meyer in an article for WIRED .

The 10 Most Controversial Psychology Studies Ever Published

Controversy is essential to scientific progress - here we digest ten of the most controversial studies in psychology’s history.

19 September 2014

By Christian Jarrett

Controversy is essential to scientific progress. As Richard Feynman said, "science is the belief in the ignorance of experts." Nothing is taken on faith, all assumptions are open to further scrutiny. It's a healthy sign therefore that psychology studies continue to generate great controversy. Often the heat is created by arguments about the logic or ethics of the methods, other times it's because of disagreements about the implications of the findings to our understanding of human nature. Here we digest ten of the most controversial studies in psychology's history. Please use the comments to have your say on these controversies, or to highlight provocative studies that you think should have made it onto our list.

The Stanford Prison Experiment

Conducted in 1971, Philip Zimbardo's experiment had to be aborted when students allocated to the role of prison guards began abusing students who were acting as prisoners. Zimbardo interpreted the events as showing that certain situations inevitably turn good people bad, a theoretical stance he later applied to the acts of abuse that occurred at the Abu Ghraib prison camp in Iraq from 2003 to 2004. This situationist interpretation has been challenged , most forcibly by the British psychologists Steve Reicher and Alex Haslam. The pair argue, on the basis of their own BBC Prison study and real-life instances of prisoner resistance, that people do not yield mindlessly to toxic environments. Rather, in any situation, power resides in the group that manages to establish a sense of shared identity. Critics also point out that Zimbardo led and inspired his abusive prison guards; that the Stanford Prison Experiment (SPE) may have attracted particular personality types; and that many guards did behave appropriately. The debate continues, as does the influence of the SPE on popular culture, so far inspiring at least two feature length movies .

Further reading

Zimbardo, P. G. (1972). Comment: Pathology of imprisonment . Society, 9(6), 4-8.

Haney, C., Banks, W. C., & Zimbardo, P. G. (1973). Study of prisoners and guards in a simulated prison . Naval Research Reviews, 9(1-17).

The Milgram "Shock Experiments"

Stanley Milgram's studies conducted in the 1960s appeared to show that many people are incredibly obedient to authority. Given the instruction from a scientist, many participants applied what they thought were deadly levels of electricity to an innocent person. Not one study, but several, Milgram's research has inspired many imitations, including in virtual reality and in the form of a French TV show . The original studies have attracted huge controversy , not only because of their ethically dubious nature, but also because of the way they have been interpreted and used to explain historical events such as the supposedly blind obedience to authority in the Nazi era. Haslam and Reicher have again been at the forefront of counter-arguments. Most recently, based on archived feedback from Milgram's participants, the pair argue that the observed obedience was far from blind – in fact many participants were pleased to have taken part, so convinced were they that their efforts were making an important contribution to science. It's also notable that many participants in fact disobeyed instructions, and in such cases, verbal prompts from the scientist were largely ineffective .

Milgram, S. (1963). Behavioral study of obedience . The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 67(4), 371.

The "Elderly-related Words Provoke Slow Walking" Experiment (and other social priming research)

One of the experiments in a 1996 paper published by John Bargh and colleagues showed that when people were exposed to words that pertained to being old, they subsequently walked away from the lab more slowly. This finding is just one of many in the field of "social priming" research, all of which suggest our minds are far more open to influence than we realise. In 2012, a different lab tried to replicate the elderly words study and failed. Professor Bargh reacted angrily . Ever since, the controversy over his study and other related findings has only intensified. Highlights of the furore include an open letter from Nobel Laureate Daniel Kahneman to researchers working in the area, and a mass replication attempt of several studies in social psychology, including social priming effects. Much of the disagreement centres around whether replication attempts in this area fail because the original effects don't exist, or because those attempting a replication lack the necessary research skills, make statistical errors, or fail to perfectly match the original research design.

Bargh, J. A., Chen, M., & Burrows, L. (1996). Automaticity of social behavior: Direct effects of trait construct and stereotype activation on action . Journal of personality and social psychology, 71(2), 230.

The Conditioning of Little Albert

Back in 1920 John Watson and his future wife Rosalie Rayner deliberately induced fears in an 11-month-old baby. They did this by exposing him to a particular animal, such as a white rat, at the same time as banging a steel bar behind his head. The research is controversial not just because it seems so unethical, but also because the results have tended to be reported in an inaccurate and overly simplified way . Many textbooks claim the study shows how fears are easily conditioned and generalised to similar stimuli; they say that after being conditioned to fear a white rat, Little Albert subsequently feared all things that were white and fluffy. In fact, the results were far messier and more inconsistent than that, and the methodology was poorly controlled. Over the last few years, controversy has also developed around the identity of poor Little Albert. In 2009, a team led by Hall Beck claimed that the baby was in fact Douglas Merritte. They later claimed that Merritte was neurologically impaired, which if true would only add to the unethical nature of the original research. However, a new paper published this year by Ben Harris and colleagues argues that Little Albert was actually a child known as Albert Barger.

Watson, J. B., & Rayner, R. (1920). Conditioned emotional reactions . Journal of Experimental Psychology, 3(1), 1.

Loftus' "Lost in The Mall" Study

In 1995 and ' 96 , Elizabeth Loftus , James Coan and Jacqueline Pickrell documented how easy it was to implant in people a fictitious memory of having been lost in a shopping mall as a child. The false childhood event is simply described to a participant alongside true events, and over a few interviews it soon becomes absorbed into the person's true memories, so that they think the experience really happened. The research and other related findings became hugely controversial because they showed how unreliable and suggestible memory can be. In particular, this cast doubt on so-called "recovered memories" of abuse that originated during sessions of psychotherapy. This is a highly sensitive area and experts continue to debate the nature of false memories, repression and recovered memories . One challenge to the "lost in the mall" study was that participants may really have had the childhood experience of having been lost, in which case Loftus' methodology was recovering lost memories of the incident rather than implanting false memories. This criticism was refuted in a later study ( pdf ) in which Loftus and her colleagues implanted in people the memory of having met Bugs Bunny at Disneyland. Cartoon aficionados will understand why this memory was definitely false.

Loftus, E. F., & Pickrell, J. E. (1995). The formation of false memories . Psychiatric annals, 25(12), 720-725.

Loftus, E. F., Coan, J. A., & Pickrell, J. E. (1996). Manufacturing false memories using bits of reality. Implicit memory and metacognition, 195-220.

Loftus, E. F. (1993). The reality of repressed memories . American psychologist, 48(5), 518.

The Daryl Bem Pre-cognition Study