- MJC Library & Learning Center

- Research Guides

Drug Abuse, Addiction, Substance Use Disorder

- Research Drug Abuse

Start Learning About Your Topic

Create research questions to focus your topic, find books in the library catalog, find articles in library databases, find web resources, cite your sources, key search words.

Use the words below to search for useful information in books and articles .

- substance use disorder

- substance abuse

- drug addiction

- substance addiction

- chemical dependency

- war on drugs

- names of specific drugs such as methamphetamine, cocaine, heroin

- opioid crisis

Background Reading:

It's important to begin your research learning something about your subject; in fact, you won't be able to create a focused, manageable thesis unless you already know something about your topic.

This step is important so that you will:

- Begin building your core knowledge about your topic

- Be able to put your topic in context

- Create research questions that drive your search for information

- Create a list of search terms that will help you find relevant information

- Know if the information you’re finding is relevant and useful

If you're working from off campus , you'll be prompted to log in just like you do for your MJC email or Canvas courses.

All of these resources are free for MJC students, faculty, & staff.

- Gale eBooks This link opens in a new window Use this database for preliminary reading as you start your research. Try searching these terms: addiction, substance abuse

Other eBooks from the MJC Library collection:

Use some of the questions below to help you narrow this broad topic. See "substance abuse" in our Developing Research Questions guide for an example of research questions on a focused study of drug abuse.

- In what ways is drug abuse a serious problem?

- What drugs are abused?

- Who abuses drugs?

- What causes people to abuse drugs?

- How do drug abusers' actions affect themselves, their families, and their communities?

- What resources and treatment are available to drug abusers?

- What are the laws pertaining to drug use?

- What are the arguments for legalizing drugs?

- What are the arguments against legalizing drugs?

- Is drug abuse best handled on a personal, local, state or federal level?

- Based on what I have learned from my research what do I think about the issue of drug abuse?

Why Use Books:

Use books to read broad overviews and detailed discussions of your topic. You can also use books to find primary sources , which are often published together in collections.

Where Do I Find Books?

You'll use the library catalog to search for books, ebooks, articles, and more.

What if MJC Doesn't Have What I Need?

If you need materials (books, articles, recordings, videos, etc.) that you cannot find in the library catalog , use our interlibrary loan service .

All of these resources are free for MJC students, faculty, & staff.

- EBSCOhost Databases This link opens in a new window Search 22 databases simultaneously that cover almost any topic you need to research at MJC. EBSCO databases include articles previously published in journals, magazines, newspapers, books, and other media outlets.

- Gale Databases This link opens in a new window Search over 35 databases simultaneously that cover almost any topic you need to research at MJC. Gale databases include articles previously published in journals, magazines, newspapers, books, and other media outlets.

- Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection This link opens in a new window Contains articles from nearly 560 scholarly journals, some dating as far back as 1965

- Access World News This link opens in a new window Search the full-text of editions of record for local, regional, and national U.S. newspapers as well as full-text content of key international sources. This is your source for The Modesto Bee from January 1989 to the present. Also includes in-depth special reports and hot topics from around the country. To access The Modesto Bee , limit your search to that publication. more... less... Watch this short video to learn how to find The Modesto Bee .

Use Google Scholar to find scholarly literature on the Web:

Browse Featured Web Sites:

- National Institute on Drug Abuse NIDA's mission is to lead the nation in bringing the power of science to bear on drug abuse and addiction. This charge has two critical components. The first is the strategic support and conduct of research across a broad range of disciplines. The second is ensuring the rapid and effective dissemination and use of the results of that research to significantly improve prevention and treatment and to inform policy as it relates to drug abuse and addiction.

- Drug Free America Foundation Drug Free America Foundation, Inc. is a drug prevention and policy organization committed to developing, promoting and sustaining national and international policies and laws that will reduce illegal drug use and drug addiction.

- Office of National Drug Control Policy A component of the Executive Office of the President, ONDCP was created by the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1988. ONDCP advises the President on drug-control issues, coordinates drug-control activities and related funding across the Federal government, and produces the annual National Drug Control Strategy, which outlines Administration efforts to reduce illicit drug use, manufacturing and trafficking, drug-related crime and violence, and drug-related health consequences.

- Drug Policy Alliance The Drug Policy Alliance (DPA) is the nation's leading organization promoting alternatives to current drug policy that are grounded in science, compassion, health and human rights.

Your instructor should tell you which citation style they want you to use. Click on the appropriate link below to learn how to format your paper and cite your sources according to a particular style.

- Chicago Style

- ASA & Other Citation Styles

- Last Updated: Apr 25, 2024 1:28 PM

- URL: https://libguides.mjc.edu/drugabuse

Except where otherwise noted, this work is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 and CC BY-NC 4.0 Licenses .

- Open access

- Published: 12 December 2022

School-based harm reduction with adolescents: a pilot study

- Nina Rose Fischer 1

Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy volume 17 , Article number: 79 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

14k Accesses

6 Citations

379 Altmetric

Metrics details

A pilot study of Safety First: Real Drug Education for Teens showed significant results pre to post curriculum with high school freshmen. Negative outcomes of drug education are linked to a failure to engage students because of developmentally inappropriate materials that include activities that have no relevance to real experiences of young people. The few harm reduction studies showed increased student drug related knowledge. Students were less likely to consume substances, and less likely to consume to harmful levels. More studies are necessary to evidence harm reduction efficacy in the classroom. The goal of this study was to measure harm reduction knowledge and behaviors, including drug policy advocacy, before and after Safety First. Data were analyzed using McNemar’s test, ANOVA, linear regression, t -tests and thematic coding. Survey results, corroborated by the qualitative findings, showed a significant increase ( p < .05) in high school freshmen harm reduction knowledge and behaviors in relationship to substance use pre to post Safety First. This increase related to a decrease in overall substance use. Harm reduction is often perceived as a controversial approach to substance use. These findings have implications for further study of what could be a promising harm reduction-based substance use intervention with teens.

Research has shown that common reasons drug education programs for youth have failed were lack of student interest because they were not developmentally appropriate, or because activities did not relate to their actual lives [ 1 , 2 ]. A review of school-based drug education studies [ 1 ] showed that for substance use education programs to be effective they should be based on the real experiences of young people, a harm reduction principle [ 1 , 2 , 3 ]. The study of Drug Policy Alliance’s (DPA) Safety First: Real Drug Education for Teens (hyperlinked) drug education curriculum for health education classes is grounded in harm reduction theory. The objective of the curriculum is to teach substance use harm reduction to support positive outcomes for young people.

Harm reduction theory

Harm reduction theory includes pragmatic strategies aimed at reducing dangers related to substance use. The theory emerged with the discovery of AIDS in 1981. Harm reduction was important for reducing transmission of blood-borne infections and for addressing drug use. Evidence has shown that harm reduction approaches greatly reduce morbidity and mortality associated with risky substance use behaviors [ 4 , 5 , 6 ] but has rarely been used to inform drug education curriculum for teenagers.

Harm reduction is an ecological systems approach, addressing drug use from the micro level, individuals, families and communities to the macro level, local, state, and federal policies and norms [ 3 , 7 , 8 , 9 ]. The theory promotes social justice with an emphasis on users’ rights, health, social and economic development, as opposed to the demonization of drug consumption [ 10 ]. Critical to the practice of harm reduction is recognizing that realities of poverty, class, racism, social isolation, past trauma, sex and gender-based discrimination and other social inequalities affect people’s capacity to address drug-related harm. Aims of this study were to measure student ability to understand and advocate for socially just harm reduction policy pre and post Safety First.

Harm reduction interventions vary according to dynamic needs of individuals and communities. The goals are to meet substance users “where they’re at,” incorporating a spectrum of strategies from abstinence, to managing use, to addressing conditions of use along with use itself. The theory adopts tenets of the trans theoretical stages of change model [ 11 , 12 ] and motivational counseling [ 13 ]. This non-judgmental, amoral approach encourages people to embark on incremental, harm-reducing goals. A harm reduction approach is congruent with what is known about adolescent development and decision-making. However, the most prevalent drug education for teens has been abstinence based, attaching stigma and moral judgment to substance use and users, instead of learning the effects and how to make informed, healthy decisions about use [ 14 , 15 ].

School based harm reduction programs have rarely received the attention of researchers. Limited studies exist about harm reduction drug education with adolescents in the US [ 1 ]. Only a few studies, from Canada, Australia and the UK showed positive results [ 1 , 2 , 16 , 17 ]. Classroom based harm reduction approaches are limited but are gaining traction in school settings because of the mixed or ineffective results from prevention and abstinence-based programs that failed to meet the real needs of youth [ 2 , 18 ]. The small pool of studies showed increase in drug related knowledge. Students were less likely to consume substances and were less likely to consume to harmful levels with themselves and peers [ 1 , 2 , 16 , 17 ]. Harm reduction can potentially address the shortfalls of prevention programs but remains contentious in the context of youth substance use, thus has not been widely studied within this population [ 2 ].

Dr. Marsha Rosenbaum, the founder of Drug Policy Alliance (DPA) developed a pamphlet for parents about harm reduction and teens in 1999 where she defined principles for school drug education and ultimately for the Safety First curriculum, “Parents and teachers are responsible for engaging students, providing them with credible information [to] make responsible decisions, avoid drug abuse, and stay safe. Curricula should be age-specific, emphasize student participation, and provide science-based educational materials.” Harm reduction principles require a non-judgmental, motivational, culturally relevant, actively engaging environment that puts student experience at the center of the curriculum [ 2 ]. Safety first includes these elements.

Safety First teaches students about different types of drugs including the short and long-term effects. Students learn how to identify viable research about drugs and discuss and present their findings in the classroom. Drug beliefs are discussed, myths are dispelled, and facts are validated. Behaviors associated with substance use are studied and discussed to inform student’s future decision making. These key principles make up the operational definition of harm reduction reflected in the Safety First curriculum and measured in the study.

The Safety First curriculum developers trained teachers that participated in the pilot studies for three, 8 hours sessions and coached them weekly for at least an hour in the content and modalities of the curriculum. The developers provided technical assistance for curriculum implementation. All teachers delivered the curriculum one to two times per week, depending on the schedule of their health classes, in each of the schools. The class lasted one semester, up to 14 sessions, at 55 minutes per class. The materials necessary for each class were all easily accessible through free downloads online and physically from the DPA curriculum developer/trainers. “How the curriculum was taught” was the variable that had the most effect on the efficacy of the curriculum and is analyzed below.

The overall goal of the study was to measure harm reduction knowledge and behaviors before and after Safety First. Diverse urban public schools were the foci for the pilots in New York City and San Francisco. Outcomes showed change from pre to post Safety First ( p < .05) in knowledge and behaviors related to substance use. The results corroborated the findings from the few other similar studies [ 1 , 2 , 16 , 17 , 19 ]. This study evidenced need for further implementation of harm reduction based substance use curriculum as part of health education in high schools and for more research to measure the effects of the curriculum with various populations and locales.

The hypotheses of this study were related to the aims of the Safety First: Real Drug Education for Teens curriculum. The curriculum developers hoped to educate freshmen high school students about harm reduction knowledge and behavior. Students will 1) Acquire critical thinking skills to access and evaluate information about alcohol and other drugs [knowledge and behavior]; 2) Understand decision-making and goal setting skills that help students make healthy choices related to substance use [knowledge and behavior]; 3) Develop personal and social strategies to manage the risks, benefits and harms of alcohol and other drug use [behavior]; 4) Know the impact of drug policies on personal and community health [knowledge]; and 5) Learn to advocate for health-oriented drug policies [behaviors]. Thus student knowledge and behavior related to substance use and harm reduction were measured before and after Safety First as part of required health education classes to determine the efficacy of the curriculum.

Data collection

Hypotheses were tested through the collection of data from validated pre/post quantitative surveys (Additional file 1 : Appendix A in the data portal: Appendices A-D can be found in the Data Portal linked here) with items that measured substance use and harm reduction knowledge and behaviors [ 20 , 21 , 22 ] pre/post qualitative focus groups and one on one interviews with semi-structured field-tested guides; and field observation, on a weekly basis in each class with a field tested template. The 14-session (55 minutes/class) curriculum was implemented and studied in four freshmen health education classes at a public school in New York City and five public schools, four classes each, in San Francisco, CA. Researchers committed to different class periods and conducted field observation on different class days weekly to ensure inter-rater reliability [ 23 ].

Demographics (Table 1 )

Participants.

Students were recruited through both purposive and random sampling methods. Drug Police Alliance (DPA) built purposeful relationships with health teachers that wanted to implement Safety First as part of their required substance use unit in New York City. Relationships were built between DPA and San Francisco health teachers through the Adolescent Health Group- a Department of Education arm that oversaw health education curriculum. Students that participated in the pre/post focus groups and interviews were chosen randomly by alternating names on the class rosters.

The total number of freshmen surveyed in the overall pool was 701. Some students did not answer demographic questions which accounted for reduced “ n ” (Table 1 ). The items “What is the definition of abstinence” and “What is the definition of harm reduction” write in examples, were added to the San Francisco survey based on the findings from the initial New York City study. Thus the “ n ” for those items is less. Prior to Safety First most students had not received any drug education (96%). Students were 14 (62%) and 15 years old (31%). Outliers included 13, 16, 17, 18 & 19 years old (7%). Students were males (54%), and female (45.6%). In New York City two identified as “Other” and one as gender non-conforming (0.4%). The largest total ethnic/racial group was Asian (43%), then Latinx (22%), mixed race (12%), white (12%), Black (9%), Middle Eastern (1.8%) and Native American (.02%). In New York City white students were the largest ethnic/racial group, however youth of color made up the majority of the student population. In San Francisco Asian students were the majority student population, then Latinx. Black and white students were next with the same representation. Most New York City students resided in Brooklyn and Manhattan while other students were closely split between Queens and the Bronx. Most San Francisco students lived in Visitacion Valley and Excelsior district. Central Richmond, Outer Sunset and the Mission district vied for second. A small number of students in both cities reported police contact, arrest and/or suspension (Table 1 ). Youth reported substance use as a reason for police involvement.

Sample comparability

The total sample included three higher and three lower achieving schools, all public. The New York City school was unique because students applied and interviewed to be accepted. Pupils were high achieving coming in, average grades were “A’s” and “B’s.” All students planned to attend college and graduate school. Two out of the five San Francisco public schools were like the New York City site in grades and graduation rates but were not admissions based. The remaining three schools had students with lower grade point averages, with more of a range when asked about future plans. All were in politically progressive US coastal cities. All were ethnically diverse, and to an extent reflective of their city’s populations. All schools consisted of students from diverse economic backgrounds. Thus, this body of research from a sample of 701 students in New York City and San Francisco could possibly be extrapolated to students in similar locales with diverse achievement levels, racial and class demographics (Table 1 ).

Data analysis

McNemar’s test was applied to analyze if the harm reduction knowledge and behavior change from before to after Safety First was significant on four critical items (Table 2 ). One-way ANOVA tests were conducted to determine if there was an effect by demographics on substance use knowledge and behavior survey responses (Additional file 1 : Appendix B-D). Linear regression was employed to determine if race or gender were predictive of responses. Qualitative responses were aggregated using thematic codes based on the emergent themes from the “write in” responses on the pre/post surveys, and the interview and focus group transcription and were transformed into quantitative codes to count and compare student responses (Table 2 below, and items 40–44 in Additional file 1 : Appendix A and Appendix B in data portal). Outcomes showed that students learned critical thinking, decision-making and harm reduction strategies. Items that did not show remarkable results, or were null, also informed future implications for Safety First.

The purpose of this pilot study was to determine if DPA’s newly rolled out Safety First: Real Drug education for Teens potentially increased harm reduction knowledge and behaviors for high school freshmen. The findings from the pre and post survey, fortified by the qualitative data, showed a likely increase in student harm reduction knowledge about drug contents and effects, drug research, positive behaviors related to substance use, and drug policies. The results demonstrated that the curriculum most likely influenced overall student substance use knowledge and behavior.

Students showed change in knowledge about, and behaviors related to harm reduction, abstinence, how to detect an opioid overdose, school specific drug policies, and how to advocate for harm reduction based drug policy after Safety First ( p < .001) (Table 2 ). Students were more involved with advocacy activities after Safety First than before ( p < .001). It is likely that learning about activism and advocacy as part of the curriculum contributed to this increase in advocacy activities ( p < .001). More youth advocated for less punitive drug policies after Safety First ( p < .001).

Themes about drug policy advocacy that emerged from the qualitative data collected from the students after the class pointed to “creating systems of support,” “reducing stigma,” and “lessening punishments.” When before Safety First the themes were advocacy for suspension and jail time. Students mentioned passing along what they learned to fellow classmates, family members, and school administrators after the class to help them improve decision-making about drugs and create fairer drug policies.

ANOVA tests revealed that the most influential effect on student response was from the school they attended, indicating that how a specific teacher taught the curriculum most likely mattered (see below and Appendices B-D). Students from specific schools post Safety First showed more understanding of drug policies, how to advocate for harm reduction based initiatives, and how to respond to an opioid overdose (Table 2 ). However, there was remarkable change across all student comprehension despite differences in how the curriculum was taught.

Likert scale pre to post

Paired t- tests were conducted to determine if there was a significant difference between students’ scores on 20 Likert Scale items after the drug education course. The scale was one strongly agree and five strongly disagree. Seventeen were significant from pre to post Safety First ( p < .001) (Additional file 1 : Appendix C). Two of the three items that had no statistical significance, “People do not become dependent upon marijuana,” and “If you overdose on a drug you will die,” still showed a shift towards disagree, the harm reduction response, through means comparison. The item “It is better not to drink water while using MDMA (“molly”)” did not show a significant change. The students agreed more with this statement after Safety First. The harm reduction answer was strongly disagree. More students also agreed that “Alcohol helps you deal with uncomfortable feelings” which showed a significant change from pre to post ( p < .037), producing a null hypothesis. This outcome provides valuable feedback to the Safety First developers. They need to review how Safety First addresses harm reduction related to MDMA and alcohol.

Gender and race

For San Francisco, an Independent Sample t -test showed “Gender” mattered on two items. More males strongly disagreed that “Marijuana is safe because it is all natural,” than females ( p < .001). More females moved to strongly agreeing that “You can die from drinking too much alcohol at one time” after Safety First than males ( p < .001). An independent t -test was administered to measure if gender had an impact on students’ scores on the Likert Scale items. There was a significant difference between males and females on two items in New York City (Additional file 1 : Appendix C). Females were less likely to agree than males that, “People do not become dependent on marijuana,” ( p < .05). Females were also less likely than males to agree that zero tolerance drug policies make schools safer ( p < .05). A linear regression demonstrated that race and gender ( p > .05) were not predictive of significantly different test scores in either city. In San Francisco more males strongly disagreed than females about the item “Marijuana is safe because it is all natural” ( p < .001). On the item “You can die from drinking too much alcohol at one time” females more strongly agreed than males ( p < .001).

An ANOVA test showed that race and religion had an effect on student responses. Asian students were more likely to move towards disagreeing with the statement “Marijuana is safe because it is all natural” which was the harm reduction response, in comparison to Latinx and Black students ( p < .001). Muslim students were more likely to move towards disagreeing with the statement “People do not become dependent upon marijuana,” in comparison to Jewish students ( p = .020). ANOVA tests showed school site had the most influence on student responses to the Likert Scale items from pre to post (Additional file 1 : Appendix C).

Pre to post: substance use behaviors

On the pre/post survey there were questions about amount and likelihood of specific substance use: 1) to understand prevalence of substance use amongst the population; and 2) to see if learning about harm reduction influenced students’ behaviors/decision making. The majority of students did not report smoking or vaping tobacco but the few students that did, smoked a significant amount, this did not change from pre to post. For marijuana, students reported decreased use from pre to post ( p < .001) (see below and Additional file 1 : Appendix D). Marijuana use with a date showed remarkable change from “I would probably not use” to almost completely “I would definitely not use marijuana” ( p < .001). There was a decrease in alcohol use from pre to post ( p < .001). There was also an overall decrease in students reporting prescription drug use ( p < .001) (Additional file 1 : Appendix D).

ANOVA tests were administered to see if the demographic factors had an effect on the substance use behavior outcomes from pre to post Safety First (Additional file 1 : Appendix D). A one-way AVOVA yielded that Asian students were more likely to move towards “I would definitely not take/smoke weed with family” than Black students ( p = .002). An independent sample t -test evidenced that young men were more likely than young women to use prescription drugs with friends ( p = .020). Results evidenced that students learned about harm reduction strategies. Prevalence of substance use amongst the population became clearer; harm reduction influenced students’ substance use behaviors/decision making from pre to post especially in relationship to marijuana and prescription drugs (Additional file 1 : Appendix D).

More students believed that their classmates were using substances after Safety First than before. This change indicated that the class could have made the students more aware of substance use prevalence. This reported prevalence reflected national numbers for this age group [ 24 ]. In 2016 SAMSHA’s comprehensive report on drug abuse and health showed that 7.3 million youth between 12 and 20 reported alcohol use. About 1 in 5 drank alcohol in the past month. An estimated 855,000 adolescents aged 12 to 17 smoked cigarettes in the past month [ 24 ]. An approximated 24.0 million 12 or older in 2016 were current users of marijuana and approximately 1.6 million adolescents used marijuana in the past month. The national study spoke to the prevalence of drug use by 14- and 15-year-old young people shown in the study [ 24 ]. Student receptivity to harm reduction strategies, substantiated collaterally through the overall reduction in student use, validated the potential relevance of this approach with high school students, starting with freshmen.

Overall harm reduction knowledge and behavior change

Thematic qualitative coding was used to identify the most emergent themes in this data. A code was assigned to prevalent themes and counted and compared to determine outcomes (Additional file 1 : Appendix B). Young people demonstrated an understanding of key harm reduction thought processes and strategies solidifying successful aspects of the Safety First curriculum [ 3 ]. Students made change in their ability to describe specific harm reduction strategies possibly due to Safety First ( p < .001). In response to “What would you do to make substance use safer?” More youth responded “1” “Realize and plan for set/setting and limits around goal setting related to substance use,” or understand the “Contents, dose, and dosage” than narrowly, “reduce harm” [ 3 ] after the class (Additional file 1 : Appendix B).

Neighborhood, class and race

Interviews unearthed themes related to a difference in student perceptions about substances based on neighborhood, class and race. Students that lived in lower income neighborhoods that were predominantly black and brown consistently believed that one should not do drugs because of the consequences observed in the community. For example, when asked, “What happens in your community when someone is under the influence of drugs or is found with drugs on them?” A 14-year-old African American young woman from Brownsville Brooklyn responded in the pre and post interview, “Arrest. People get shot. People go to the hospital. People go to jail.”

When asked the same question before the class, a white female student that lived in the Upper Westside of Manhattan stated,

I have to admit that I live in a privileged neighborhood. So the use of drugs actually wouldn’t be that bad. Because it’s not like there’s the strongest police force patrolling my neighborhood, which is a huge part of it, like a part that I have to admit.

When asked the same question after Safety First she answered, “… there’s such a low risk for me to be put in a position where I’m...criminalized. So I don’t have to worry walking down the street if I have weed with me or something.”

When asked, “Are different groups of people treated differently if they have or are using drugs? If so, how?” the same African American young woman above explained the neighborhood, class and race differences:

If you seem like a person from a rich up town neighborhood or family using them [drugs], you would immediately think that they got them from somebody else. And then you will look to someone from a poor community who has them [drugs] and blame them, which is a stereotype that I really hate. I think that most of the times if someone from a rich family gets caught with drugs, they’re not gonna get nothing more than a warning. If someone from a poor community or an African or the Hispanic race gets caught, they are going to jail.

A young white woman from an affluent neighborhood’s pre response corroborated her response through her answer to the same question,

At my middle school there was a situation where a guy, mixed race black and white, bought weed for his friend, a white girl. Then she was high in school with that weed. She didn’t even get into as much trouble as the kid who bought it. Everyone in the school was pointing out, he’s biracial, so he’s black. He had a two-week out of school suspension for buying her the weed off campus and she had nothing.

Her post response to the question, “Are different groups of people treated differently if they have or are using drugs? If so, how?” was informed by the drug policy race and class session,

For sure. Low-income groups, African American communities, people of color in general, are so much quicker to be criminalized and prosecuted for having drugs, especially marijuana. I know now that there’s a disproportionate incarceration rate for men of color caught with marijuana.

Themes from student interviews, focus groups, and “write in” answers about the unequal treatment of people using or selling substances because of race, class and neighborhood reflected class lessons from Safety First about inequality in drug policy implementation. The findings indicated that the class increased student knowledge about critical social justice topics. Social justice is key to the harm reduction approach [ 25 ].

Student evaluation of safety first

The majority of students had a positive evaluation of Safety First. Fifty-five percent ( n = 389) of students reported that they would recommend Safety First. Thirty-nine percent ( n = 274) stated they would recommend Safety First with some changes. Six percent ( n = 45) relayed they would not recommend Safety First. Thus 94% of the students believed Safety First was a worthwhile experience. Quantitative coding of the most prevalent themes from the qualitative data sources informed what the students liked best about Safety First.

Direct quotes exemplified the coded themes: Code “1” learning about harm reduction strategies, including what to do in an overdose, a non-judgmental approach to teaching drug education, and I liked ‘everything’: “I actually learned a lot and didn’t feel like I was just being told that drugs were awful, and trying them makes you an awful person,” “I learned how to be safe and smart;” “High schoolers are more prepared for anything involving drug usage and overdose;” “It was not one of those ‘DARE’ abstinence only curriculums where they try to convince you that weed is a gateway to heroine and you will die if you try molly. I actually felt like I learned something that wasn’t fear based;” and “You seem to have tried really hard to make this curriculum great and it shows.” Code “2” learning about different substances: “I like learning about the different effects different drugs can do to your brain and body.” Code “3” the interactive/engaging activities and liking how the teacher taught the class overall, “I liked the different activities that we did that demonstrated different scenarios and substances, also the teacher explained it very well” and “I liked the part where we drank the Koolaid for a party experiment.” Code “4” videos and mixed media, “The videos including the ASAP science videos,” and “I absolutely love that youtube channel,” “I liked the videos, they were informative.” Code “5” was “Nothing” or “I Don’t Know.” “Learning about specific substances” ( n = 216, 40%) was what the majority of students liked about Safety First. Students wrote “Nothing” or Didn’t Know second ( n = 137, 25%); the interactive and engaging activities third ( n = 87, 16%); learning harm reduction strategies fourth ( n = 81, 15%) and videos were the least mentioned ( n = 18, 3.3%).

“No Judgement,” “Harm Reduction Skills,” and “Real Drug Education” were other themes that emerged in the post evaluation of the curriculum: “I liked that it wasn’t very judgmental and understood that the chance of kids trying drugs is likely. I also liked the harm reduction strategies,” “I liked how the curriculum went in depth about the side effects of drugs and taught us how to research and find correct information about a drug. It was well organized, and I got so much out of it,” and “It did not look down on people who used! Safety First stated facts and was looking out for our well beings; no biased opinions.”

The data illustrated that youth learned about both harm reduction skills and knowledge, appreciated the non-judgmental element of the approach and enjoyed when it was taught using dynamic, interactive teaching modalities with mixed media.

The results demonstrated that after Safety First student harm reduction knowledge and behavior changed after Safety First ( p < .05). Prevalence of substance use amongst this student population became clearer. The issue of prevalence, as described above, is quite critical. Regardless of their moral beliefs parents, teachers, administrators, policy makers and a continuum of social services need to know that 14- and 15-year old’s are using substances, and for some, a remarkable amount daily and weekly (see below and Additional file 1 : Appendix D). Entrenched beliefs by policy makers and institutions that “abstinence-based drug education is more effective” persist even with the preponderance of evidence to expose their inefficacy and actual harm [ 14 , 15 ].

The goals of the Safety First developers did not expressly include reducing substance use. True harm reduction does not stigmatize substance use or assume that it is inevitably “wrong” or “dangerous.” [ 3 ] As a researcher I was curious about whether there would be a collateral effect from the curriculum on student drug use, since institutions that promote drug education often see reduced use and abstinence as a goal. Collateral findings did show a significant relationship ( p < .05) between increased knowledge and skills with reduced substance use over the course of the semester. Teaching students harm reduction influenced students’ substance use behaviors/decision making from pre to post especially in relationship to marijuana and prescription drugs (below and Additional file 1 : Appendix D).

Likert scale items

Seventeen of the Likert scale items on the pre/post survey were significant from pre to post Safety First because students’ answers demonstrated an increase in harm reduction knowledge and behaviors ( p < .001) (Additional file 1 : Appendix C). The item “It is better not to drink water while using MDMA (“molly”)” did not show a significant change. The students agreed more with this statement after Safety First. The harm reduction answer was to “strongly disagree.” More students also agreed that “Alcohol helps you deal with uncomfortable feelings” which showed a significant change from pre to post ( p = .037), producing a null hypothesis. The harm reduction answer was to “strongly disagree.” This outcome provided valuable feedback to the Safety First developers. They need to review how Safety First addresses harm reduction related to MDMA and alcohol.

The teaching effect

ANOVA tests revealed that the most influential effect on student knowledge and behavior change was from the school they attended. How the curriculum was taught was the most influential variable. Teachers need training and coaching about how to implement Safety First. Technical assistance must be available from the purveyor or other trained experts to ensure fidelity. Importantly, there was still remarkable change across all student comprehension despite differences in how the curriculum was taught.

Study limitations with recommendations

The recommendations that stem from the “Discussion” are to include more curricula about MDMA and alcohol; provide coaching, training and technical assistance for teachers to adhere to fidelity of Safety First and to use dynamic, interactive, engaging pedagogical modalities in the classroom.

Abundance of data

An abundance of data points were collected for this study. More explication and discussion of fidelity issues, classroom observations and teacher evaluations are rich fodder for future manuscripts. Further discussion and recommendations could be mined from additional analysis. An article that dives more deeply into solely the qualitative data would give nuanced texture to the unique narrative of the Safety First classroom experience. Ethnography and phenomenology could both be used for the data analysis of interviews, focus groups, field observations and “write in” survey data to produce additional, compelling literature.

Sustainability

Although there have been no longitudinal studies of a high school substance use harm reduction curriculum, research of drug prevention programs over time showed that positive effects last throughout high school but taper off after [ 26 ]. Most schools only require one semester of health. This pilot study showed that in 14 classes students learned advocacy skills to promote creative harm reduction oriented policies. A sustainability recommendation is for drug policy organizations to spearhead advocacy groups on school campuses so students can sustain the harm reduction messages throughout and after high school. Longitudinal studies to measure student behavior and knowledge over time are key to the sustainability of Safety First.

Transportability

Results from public schools in two urban coastal cities showed a remarkable change from pre to post Safety First. This study tested student response across literacy, class and achievement levels. The study population were an integrated, multicultural cohort of 14- and 15-year old’s in urban areas, and these discrete demographic groups- Asian (296), Latinx (141), male (381) and female (311) exceeded 100. A sample must be over 100 to be considered generalizable [ 27 ]. Thus, in order to expand the transportability of the results it is integral to see how Safety First works in suburban, rural or small predominantly white locales; or with predominantly Black youth in smaller towns or large cities [ 23 ]. Lesbian, Bisexual, Trans, Non-Binary and Gay youth should be study participants. Youth in “last chance” schools, on probation, in detention or elite private schools should also be identified. Can Safety First be implemented successfully in a different type of institution? A drug treatment facility or a community-based organization? Does the curriculum work with middle school youth or older teens/young adults? Future research should serve youth of different ages, across similar and new demographic factors, and in environments outside the purview of this study.

Randomized control groups

The scope and scale of this study did not allow for the randomized control groups. These would have allowed a direct comparison of the outcomes for young people that either did not have a substance use component in their health class or had been exposed to a prevention and/or abstinence-based curriculum. Future studies should include randomized control groups across various populations of youth. Albeit, this pre/post study design did show baseline student knowledge and behaviors and the effects of Safety first on students after the curriculum.

The Safety First: Real Drug Education for Teens curriculum had significant effect on a diverse population of freshmen from six public high schools in the United States. Students acquired critical thinking skills to access and evaluate information about alcohol and other drugs; they had a better understanding of decision-making and goal setting skills that increased healthy choices related to substance use; they developed personal and social strategies to manage the risks, benefits and harms of alcohol and other drug use; they knew the impact of drug policies on personal and community health; and students learned to advocate for health-oriented drug policies. Outcomes inform future research. The implications of the results were that Safety First should be tested at comparable and new school sites. Further study should include randomized survey samples and control groups. The generalizability of the results should be measured with similar and different populations, as well as test the same students overtime to show the endurance of the effects.

The results are timely. Student knowledge increase related to the detection and response to an opioid overdose is particularly relevant because of national prevalence [ 28 ]. Student interviews about unequal treatment of people using or selling drugs based on race, class, gender and neighborhood illustrated the importance of understanding the intersection particularly between drug policy, race and class. There are a dearth of studies about harm reduction in the classroom [ 2 , 16 , 19 ]. These pilot findings are seed for future research to support harm reduction education for youth.

Availability of data and materials

Data is included in the Tables below and Additional Tables and Appendices accessible through this link to DropBox .

McBride N. A systematic review of school drug education. Health Educ Res. 2003;18(6):729–42.

Article Google Scholar

Jenkins EK, Slemon A, Haines-Saah RJ. Developing harm reduction in the context of youth substance use: insights from a multi-site qualitative analysis of young people’s harm minimization strategies. Harm Reduct J. 2017:14–53.

Marlatt GA, Larimer ME, Witkiewitz K, editors. Harm reduction pragmatic strategies for managing high risk behaviors. 2nd ed. New York and London: Guildford Press; 2012.

Google Scholar

Langendam MW, van Brussel GH, Coutinho RA, van Ameijden EJ. The impact of harm-reduction-based methadone treatment on mortality among heroin users. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:774–8.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Amundsen EJ. Measuring prevention of HIV among injecting drug users. Addiction. 2006;101:911–2.

Odets W. AIDS education and harm reduction for gay men: psychological approaches for the 21st century. AIDS Public Policy J. 1991;9(1):1–18.

Duncan D, Nicholson T, Cli†ord P, Hawkins W, Petosa R. Harm reduction: an emerging new paradigm for drug education. J Drug Educ. 1994;24:281–90.

Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1979.

Moffat BM, Haines-Saah RJ, Johnson JL. From didactic to dialogue: assessing the use of an innovative classroom resource to support decision-making about cannabis use. Drug Educ Prev Policy. 2016;24:85–95.

Roche AM, Evans KR, Stanton WR. Harm reduction: roads less traveled to the holy grail. Addiction. 1997;92:1207–12.

Elovich R, Staying negative. It is not automatic: a harm-reduction approach to substance use and sex. AIDS Public Policy J. 1996;11(2):66–77.

CAS Google Scholar

Prochaska JO, Redding C, Harlow L, Rossi J, Rossi J, Velicer W. The transtheoretical model of change and HIV prevention: a review. Health Educ Q. 1994;21:471–86.

Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: preparing people to change addictive behavior. New York: Guilford; 1991.

Cima R. DARE: the anti-drug program that never actually worked: Priceonomics; 2016.

Ennett S, Tobler NS, Ringwalt C, Flewelling R. How effective is drug abuse resistance education? a meta-analysis of Project Dare outcome evaluations. Am J Public Health. 1994;84(9):1394–401.

Poulin C, Nicholson J. Should harm minimization as an approach to adolescent substance use be embraced by junior and senior high schools? Empirical evidence from an integrated school- and community-based demonstration intervention addressing drug use among adolescents. Int J Drug Policy. 2005;16(6):403–14.

McKay M, Sumnall H, McBride N, Harvey S. The differential impact of a classroom-based, alcohol harm reduction intervention, on adolescents with different alcohol use experiences: a multi-level growth modeling analysis. J Adolesc. 2014;37:1057–67.

Farrugia A. Assembling the dominant accounts of youth drug use in Australian harm reduction drug education. Int J Drug Policy. 2014;25:663–72.

Ringwalt CL, Clark HK, Hanley S, Shamblen SR, Flewelling RL. Project ALERT: a cluster randomized trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163(7):625–32.

Ringwalt CL, Clark HK, Hanley S, Shamblen SR, Flewelling RL. The effects of project ALERT one year past curriculum completion. Prev Sci. 2010;11(2):172–84.

Kovach HC, Ringwalt CL, Hanley S, Shamblen SR. Project Alert's effects on adolescents' prodrug beliefs: a replication and extension study. Health Educ Behav. 2010;37(3):357–76.

Armstrong D, Gosling A, Weinman J, Marteau T. The place of inter-rater reliability in qualitative research: an empirical study. Sociology. 1997;31(3):597–606.

Ahrnsbrak R, Jonaki B, Hedden SL, Lipari RN, Park-Lee E. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: results from the 2016 National Survey on drug use and health. Originating Office Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2017.

Bernadette P. Harm reduction through a social justice lens. Int J Drug Policy. 2008;19(1):10–7.

Lohrmann DK, Ater R, Greene R, Younoszai T. Long-term impact of a district-wide school/community-based substance abuse prevention initiative on gateway drug use. J Drug Educ. 2005;35(3):233–53.

Burmeister E, Aitken L. Sample size: how many is enough? Australian Critical Quality. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2012.

Kolodny A, Courtwright DT, Hwang CS, Kreiner P, Eadie JL, Clark TW, et al. The prescription opioid and heroin crisis: a public health approach to an epidemic of addiction. Annu Rev Public Health. 2015:559–74.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not Applicable.

The Drug Police Alliance awarded funding for this study through the Research Foundation of the City University of New York.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

John Jay College of Criminal Justice, 524 W. 59th Street Rm. 6.65.09, New York, NY, 91001, USA

Nina Rose Fischer

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

This author developed the data collection tools, analyzed the data and wrote up the findings. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

NDr. Nina Rose Fischer is an Associate Professor at City University of New York John Jay College of Criminal Justice in Interdisciplinary Studies where she develops courses about social justice. She is the Co-Director of the prestigious Vera Fellows Program for social justice. She has 25 years experience in harm reduction and youth justice as an organizer, therapist, administrator, policy analyst and researcher. She is currently Principal Investigator on three original research projects 1) youth and police relations; 2) substance use harm reduction; and 3) arrest diversion. She published an article: Interdependent fates: Youth and police—Can they make peace? Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology : https://doi.org/10.1037/pac0000466 and a book called The Case for Youth Police Initiative: Interdependent Fates and the Power of Peace, an ethnographic exploration of young people and police relations; as well as recommendations for how law enforcement can benefit from social welfare infrastructure. She is working on creative avenues to disseminate her findings including a docuseries about young people and police in hostile environments envisioning what safety really means. Critical race, class and gender analyses are central to her work as an activist scholar.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Nina Rose Fischer .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Institutional Review Board through the Graduate Center City University of New York approval was granted before the study was conducted with human subjects. The reference number is 2017–0746. The date of initial registration was June 29th, 2017, and continued approval has been granted through August 8th, 2022.

Consent for publication

All data collection tools were anonymous. No identifying information was collected. Parental Consent and Adolescent Assent forms were signed by students and parents allowing their adolescent children to participate in the study. Teachers also signed consent forms.

Competing interests

This author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1., summary pre and post substance use behaviors.

Tobacco use showed no significant change form pre to post. On average, youth reported being with youth that used tobacco or that they used tobacco themselves monthly or never (3.70) before and after Safety First. On average, youth reported being with youth that used alcohol, or using alcohol themselves monthly or never (3.70) before and after Safety First. Tobacco and alcohol showed no significant change from pre to post. Marijuana was a different story. Students believed that fewer peers used marijuana on average (31%) after Safety First than before the harm reduction unit (43%). Students reported spending more time with students that used marijuana on average from monthly or never (Mean-μ = 3.29) closer to monthly (μ = 3.15). Youth reported marijuana use was monthly or never (μ = 3.80) pre to post.

Marijuana use showed a significant change from “I would probably not use” to almost completely “I would definitely not use” if “...your date is using marijuana” after Safety First. Prescription drug use and alcohol use showed no significant change from pre to post, staying an average between “I would probably not use” to “I would definitely not use.”

Students made a remarkable change from pre to post in their ability to describe specific harm reduction strategies in response to “What would you do to make substance use safer? ” Average youth response moved from “2” just reduce harm (μ = 2.25) to “1” Realize and plan for set/setting and limits around goal setting related to substance use, or Contents, Dose, Dosage including reduction of use (μ = 1.60).

An ANOVA was administered to see if any of the demographic factors had an effect on the substance use behavior outcomes from pre to post Safety First. Race and gender had the only effects. A one-way AVOVA yielded that Asian students were more likely to move towards “I would definitely not take/smoke weed with family” than black students [F(6, 556) = 3.50, p = .002]. An independent sample t -test evidenced that young men were more likely than young women to use prescription drugs with friends (Mean-μ = −.92) to (μ = − 1.31), t(111) = 2.35, p = .020.

The above results evidenced that the curriculum taught the students about harm reduction strategies. Prevalence of substance use amongst the population became more clear; harm reduction seemed to influence students’ substance use behaviors/decision making from pre to post Safety First, especially in relationship to marijuana and prescription drugs; and students clearly demonstrated an increase in knowledge of harm reduction strategies.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Fischer, N.R. School-based harm reduction with adolescents: a pilot study. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy 17 , 79 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13011-022-00502-1

Download citation

Accepted : 27 October 2022

Published : 12 December 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13011-022-00502-1

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Harm reduction education

- Classroom based substance use curriculum

- Adolescent substance use

- Mixed methods research

Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy

ISSN: 1747-597X

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Grant Writing Academy Newsletter

How to Write a Grant Proposal for Drug Prevention Programs

Craft a winning grant proposal for drug prevention program.

The importance of drug prevention programs cannot be overstated. These programs play a pivotal role in society, acting as a barrier between potential drug abuse and healthy living.

However, funding remains a constant challenge for such initiatives. Securing grants can be a vital lifeline for these programs, but to do so, you need a compelling grant proposal.

Here's how to craft one.

1. Understand Your Funder

Before you begin writing, research potential funders. Understand their priorities, past grants, and their objectives. Aligning your program with the funder’s goals increases the chances of your proposal being accepted.

Example: If a potential funder has previously supported programs focusing on youth drug prevention, emphasize how your initiative targets young individuals, perhaps through school-based campaigns or youth mentorship programs.

2. Executive Summary

This is the first thing potential funders will read. Keep it concise, yet powerful. Introduce the problem, your solution, the amount you’re requesting, and a brief overview of the program's expected outcomes.

Example: “Youth substance abuse in XYZ city has risen by 20% in the past five years. Our organization seeks $50,000 to launch a comprehensive drug prevention initiative targeting schools, aiming to reduce this statistic by 50% within two years.”

3. Introduction to Your Organization

Detail your organization's history, accomplishments, and its experience in drug prevention or related fields. This establishes your credibility.

Example: “Founded in 2010, ABC Foundation has successfully spearheaded 15 community health programs, directly impacting over 10,000 lives.”

4. Needs Statement

Clearly articulate the problem. Use statistics, stories, or case studies to paint a vivid picture of why the program is crucial.

Example: “In XYZ city, one in every five high school students admitted to trying illicit substances. This alarming statistic is compounded by an increase in drug-related crimes and school dropouts.”

5. Program Description

Detail the ins and outs of your drug prevention program. This includes:

Goals and Objectives: Clear, measurable targets your program aims to achieve. Example: “Goal: Reduce youth drug experimentation by 50% within two years. Objective 1: Reach 10,000 students with our school-based program.”

Methods: How you intend to achieve these objectives. Example: “Collaborate with local schools to incorporate drug education into their curriculum.”

Staff/Volunteers: List and describe the key players. Example: “Led by Dr. Jane Doe, a professional with 10 years of experience in drug prevention.”

Timeline: A detailed timeframe of your program’s activities. Example: “January - March: Program design and staff training. April - December: School engagements and community workshops.”

6. Evaluation

Describe how you’ll measure the program’s success. Funders want accountability.

Example: “A quarterly survey will be conducted in participating schools to gauge the program's effectiveness, tracking changes in students' attitudes, knowledge, and behavior concerning drug use.”

Provide a clear, itemized budget. This should include:

Direct Costs: Money that goes straight into the program, like materials, salaries, and equipment.

Indirect Costs: Overhead or administrative expenses.

Income: Potential revenue, like donations or other grants.

Justifications: Explain any costs that might raise questions.

Example: “$10,000 - Educational materials for schools. This ensures up-to-date, high-quality resources that engage students effectively.”

8. Sustainability

Grants often cover only a specific period. Demonstrate how you intend to sustain the program afterward.

Example: “Post-grant, we intend to partner with local businesses for sponsorship, host fundraising events, and integrate a small fee for some services, ensuring the program's continuity.”

9. Conclusion

Reiterate the importance of the program, the difference the grant will make, and express gratitude for the funder’s consideration.

Example: “With the rise of drug abuse in XYZ city, your support can be transformative. Together, we can ensure a brighter, healthier future for our youth. Thank you for considering our proposal.”

10. Supporting Documents

Include any additional materials that strengthen your case: letters of support, organizational charts, endorsements, or relevant news articles.

Example: A letter from the city's mayor, endorsing your program and its importance to the community.

Be clear and concise: Avoid jargon or overly technical language.

Tailor your proposal: Each funder is unique. Modify your proposal to cater to each funder’s priorities.

Follow guidelines: If the funder provides a specific format or guidelines, adhere to them strictly.

Conclusion:

Writing a grant proposal for drug prevention programs requires research, clarity, and a deep understanding of both the issue at hand and the potential funder. By clearly articulating the need, outlining your approach, and demonstrating the potential impact and sustainability, you significantly increase your chances of securing that much-needed grant for your program.

Remember, the goal is not just to secure funds but to bring about tangible, lasting change in the community.

Invitation: Exclusive Live Workshop on Grant Writing in Abuja

We are excited to extend an exclusive invitation to you for our upcoming Live Workshop on Grant Writing , scheduled to be held in the heart of Abuja by the end of November. This is a golden opportunity for individuals and organizations aiming to sharpen their grant-writing skills, gain in-depth insights into the world of grant-making, and increase their chances of securing essential funding.

Virtual Participation: Zoom Into Mastery

Can’t be there in person? No worries. Even if you can’t make it to Abuja physically, you don’t have to miss out on this transformative experience.

Register and make your payment , and we’ll connect you virtually via Zoom, ensuring you receive the same rich content and interactive learning as those attending live. Make payment here.

Event Details:

Date: 27th November, 2023 – 1st December, 2023

Time: 9:00 AM - 3:00 PM

Venue: Abuja, Nigeria

Why Attend?

Expert-Led Sessions: Our panel consists of renowned grant-writing professionals with a track record of securing millions in funds for diverse projects.

Hands-On Training: Dive deep into real-world grant applications, understand the do's and don'ts, and refine your approach with practical exercises.

Networking Opportunities: Rub shoulders with fellow grant writers, and potential collaborators.

Comprehensive Material: Every participant will receive a curated grant-writing toolkit, complete with templates, sample applications, and a list of potential grantors.

Workshop Highlights:

Foundation of Grant Writing: Learn the fundamental principles that set apart winning proposals from the rest.

Narrative Crafting: Uncover the art of storytelling in grant applications, ensuring your project stands out and resonates with funders.

Budgeting & Financial Projections: Understand how to create a robust and transparent financial plan that instills confidence in potential grantors.

Tailoring Applications: Every funder is unique. Gain insights into tailoring your applications to resonate with specific grantors' missions and values.

Feedback & Reviews: Get your past or draft applications reviewed by experts, garner constructive feedback, and learn ways to enhance them.

Registration Details:

Early Bird Fee: N350,000 (Includes workshop materials, lunch, and a certificate of participation.)

Early Bird Offer: Register by November 10th and avail a 10% discount!

How to Make Payment : Click here to make your payment and register or call us at +2348111442950 or email at [email protected] .

Late Registration Fee: N500,000

Note: Seats are limited, and registrations will be on a first-come, first-served basis. So, hurry and secure your spot today!

Join Us & Transform Your Grant Writing Journey!

The world of grant-making is competitive, but with the right skills and approach, you can significantly increase your chances of success. Whether you're a beginner stepping into the realm of grant writing or a seasoned professional looking for advanced strategies, this workshop promises value at every level.

Abuja, with its vibrant community of NGOs, startups, and institutions, is the perfect backdrop for this transformative event.

So, mark your calendars, spread the word, and gear up for a day of learning, networking, and empowerment!

We eagerly look forward to welcoming you and embarking on this enriching journey together.

Essential Reads for Grant Writing Excellence

Grants can unlock vast potentials, but securing them? That's an art and a science. Whether you're new to the field or looking to enhance your skills, these hand-picked titles will elevate your grant-writing game:

1. Advanced Grant Writing

Go Beyond Basics: Dive into strategies and techniques that make proposals irresistible. With insights into a reviewer's mindset, stand out and shine even in fierce competition.

2. Grant Readiness Guide:

Be Grant-Ready: Ensure your organization isn't just applying but is truly ready to manage and utilize grants. Streamline, assess, and position yourself for success from the get-go.

3. Mastering Grant Writing:

From Novice to Pro: Covering the entire spectrum of grant writing, this guide offers invaluable tips, examples, etc.. It's your blueprint to mastering the craft.

4. The Small Business Guide to Winning Grants:

Business-Specific Brilliance: Designed for small businesses, navigate the unique challenges you face. Find, apply, and win grants tailored just for you.

5. Becoming the Grant Guru:

Think, Act, Succeed: More than writing – it's about strategy and mindset. Step into the shoes of a guru, understand funder desires, and become indispensable in the grant world.

Why These Titles?

Securing grants isn't just about paperwork; it's about alignment, narrative, and persuasion. The above titles are your arsenal in this endeavor, carefully crafted to offer actionable insights for every level of expertise.

In a realm where competition is stiff, your edge lies in continuous learning and adaptation.

Grab these books, absorb their wisdom, and position yourself as the top contender in the grant game. Your journey to becoming a grant virtuoso begins with these pages. Dive in!

Unlock Your Grant Success!

Join our email list now for exclusive grant-writing tips and unique grant opportunities delivered straight to your inbox. Click here to Subscribe . Don't miss out!

Ready for more?

- Open access

- Published: 13 November 2021

Risk and protective factors of drug abuse among adolescents: a systematic review

- Azmawati Mohammed Nawi 1 ,

- Rozmi Ismail 2 ,

- Fauziah Ibrahim 2 ,

- Mohd Rohaizat Hassan 1 ,

- Mohd Rizal Abdul Manaf 1 ,

- Noh Amit 3 ,

- Norhayati Ibrahim 3 &

- Nurul Shafini Shafurdin 2

BMC Public Health volume 21 , Article number: 2088 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

148k Accesses

114 Citations

20 Altmetric

Metrics details

Drug abuse is detrimental, and excessive drug usage is a worldwide problem. Drug usage typically begins during adolescence. Factors for drug abuse include a variety of protective and risk factors. Hence, this systematic review aimed to determine the risk and protective factors of drug abuse among adolescents worldwide.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) was adopted for the review which utilized three main journal databases, namely PubMed, EBSCOhost, and Web of Science. Tobacco addiction and alcohol abuse were excluded in this review. Retrieved citations were screened, and the data were extracted based on strict inclusion and exclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria include the article being full text, published from the year 2016 until 2020 and provided via open access resource or subscribed to by the institution. Quality assessment was done using Mixed Methods Appraisal Tools (MMAT) version 2018 to assess the methodological quality of the included studies. Given the heterogeneity of the included studies, a descriptive synthesis of the included studies was undertaken.

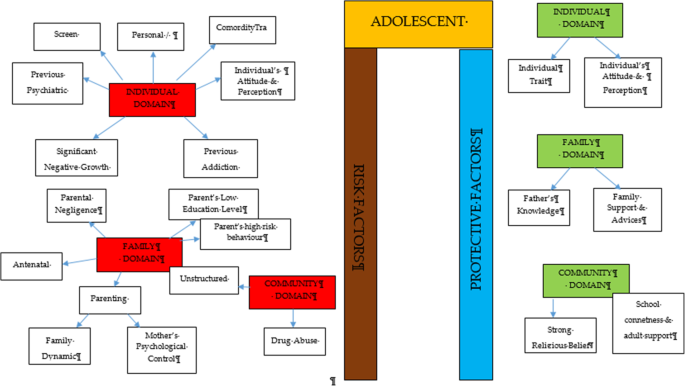

Out of 425 articles identified, 22 quantitative articles and one qualitative article were included in the final review. Both the risk and protective factors obtained were categorized into three main domains: individual, family, and community factors. The individual risk factors identified were traits of high impulsivity; rebelliousness; emotional regulation impairment, low religious, pain catastrophic, homework completeness, total screen time and alexithymia; the experience of maltreatment or a negative upbringing; having psychiatric disorders such as conduct problems and major depressive disorder; previous e-cigarette exposure; behavioral addiction; low-perceived risk; high-perceived drug accessibility; and high-attitude to use synthetic drugs. The familial risk factors were prenatal maternal smoking; poor maternal psychological control; low parental education; negligence; poor supervision; uncontrolled pocket money; and the presence of substance-using family members. One community risk factor reported was having peers who abuse drugs. The protective factors determined were individual traits of optimism; a high level of mindfulness; having social phobia; having strong beliefs against substance abuse; the desire to maintain one’s health; high paternal awareness of drug abuse; school connectedness; structured activity and having strong religious beliefs.

The outcomes of this review suggest a complex interaction between a multitude of factors influencing adolescent drug abuse. Therefore, successful adolescent drug abuse prevention programs will require extensive work at all levels of domains.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Drug abuse is a global problem; 5.6% of the global population aged 15–64 years used drugs at least once during 2016 [ 1 ]. The usage of drugs among younger people has been shown to be higher than that among older people for most drugs. Drug abuse is also on the rise in many ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) countries, especially among young males between 15 and 30 years of age. The increased burden due to drug abuse among adolescents and young adults was shown by the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study in 2013 [ 2 ]. About 14% of the total health burden in young men is caused by alcohol and drug abuse. Younger people are also more likely to die from substance use disorders [ 3 ], and cannabis is the drug of choice among such users [ 4 ].

Adolescents are the group of people most prone to addiction [ 5 ]. The critical age of initiation of drug use begins during the adolescent period, and the maximum usage of drugs occurs among young people aged 18–25 years old [ 1 ]. During this period, adolescents have a strong inclination toward experimentation, curiosity, susceptibility to peer pressure, rebellion against authority, and poor self-worth, which makes such individuals vulnerable to drug abuse [ 2 ]. During adolescence, the basic development process generally involves changing relations between the individual and the multiple levels of the context within which the young person is accustomed. Variation in the substance and timing of these relations promotes diversity in adolescence and represents sources of risk or protective factors across this life period [ 6 ]. All these factors are crucial to helping young people develop their full potential and attain the best health in the transition to adulthood. Abusing drugs impairs the successful transition to adulthood by impairing the development of critical thinking and the learning of crucial cognitive skills [ 7 ]. Adolescents who abuse drugs are also reported to have higher rates of physical and mental illness and reduced overall health and well-being [ 8 ].

The absence of protective factors and the presence of risk factors predispose adolescents to drug abuse. Some of the risk factors are the presence of early mental and behavioral health problems, peer pressure, poorly equipped schools, poverty, poor parental supervision and relationships, a poor family structure, a lack of opportunities, isolation, gender, and accessibility to drugs [ 9 ]. The protective factors include high self-esteem, religiosity, grit, peer factors, self-control, parental monitoring, academic competence, anti-drug use policies, and strong neighborhood attachment [ 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 ].

The majority of previous systematic reviews done worldwide on drug usage focused on the mental, psychological, or social consequences of substance abuse [ 16 , 17 , 18 ], while some focused only on risk and protective factors for the non-medical use of prescription drugs among youths [ 19 ]. A few studies focused only on the risk factors of single drug usage among adolescents [ 20 ]. Therefore, the development of the current systematic review is based on the main research question: What is the current risk and protective factors among adolescent on the involvement with drug abuse? To the best of our knowledge, there is limited evidence from systematic reviews that explores the risk and protective factors among the adolescent population involved in drug abuse. Especially among developing countries, such as those in South East Asia, such research on the risk and protective factors for drug abuse is scarce. Furthermore, this review will shed light on the recent trends of risk and protective factors and provide insight into the main focus factors for prevention and control activities program. Additionally, this review will provide information on how these risk and protective factors change throughout various developmental stages. Therefore, the objective of this systematic review was to determine the risk and protective factors of drug abuse among adolescents worldwide. This paper thus fills in the gaps of previous studies and adds to the existing body of knowledge. In addition, this review may benefit certain parties in developing countries like Malaysia, where the national response to drugs is developing in terms of harm reduction, prison sentences, drug treatments, law enforcement responses, and civil society participation.

This systematic review was conducted using three databases, PubMed, EBSCOhost, and Web of Science, considering the easy access and wide coverage of reliable journals, focusing on the risk and protective factors of drug abuse among adolescents from 2016 until December 2020. The search was limited to the last 5 years to focus only on the most recent findings related to risk and protective factors. The search strategy employed was performed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) checklist.

A preliminary search was conducted to identify appropriate keywords and determine whether this review was feasible. Subsequently, the related keywords were searched using online thesauruses, online dictionaries, and online encyclopedias. These keywords were verified and validated by an academic professor at the National University of Malaysia. The keywords used as shown in Table 1 .

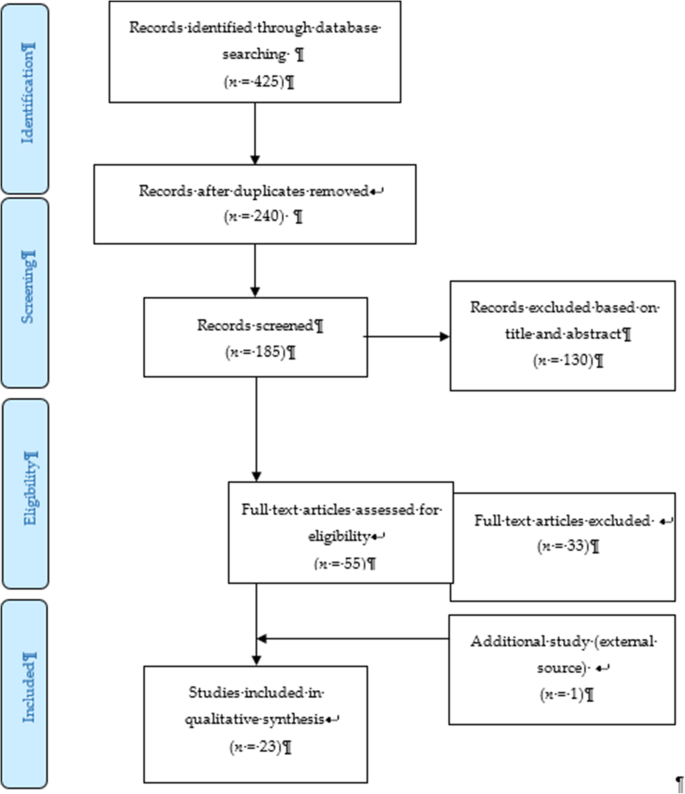

Selection criteria

The systematic review process for searching the articles was carried out via the steps shown in Fig. 1 . Firstly, screening was done to remove duplicate articles from the selected search engines. A total of 240 articles were removed in this stage. Titles and abstracts were screened based on the relevancy of the titles to the inclusion and exclusion criteria and the objectives. The inclusion criteria were full text original articles, open access articles or articles subscribed to by the institution, observation and intervention study design and English language articles. The exclusion criteria in this search were (a) case study articles, (b) systematic and narrative review paper articles, (c) non-adolescent-based analyses, (d) non-English articles, and (e) articles focusing on smoking (nicotine) and alcohol-related issues only. A total of 130 articles were excluded after title and abstract screening, leaving 55 articles to be assessed for eligibility. The full text of each article was obtained, and each full article was checked thoroughly to determine if it would fulfil the inclusion criteria and objectives of this study. Each of the authors compared their list of potentially relevant articles and discussed their selections until a final agreement was obtained. A total of 22 articles were accepted to be included in this review. Most of the excluded articles were excluded because the population was not of the target age range—i.e., featuring subjects with an age > 18 years, a cohort born in 1965–1975, or undergraduate college students; the subject matter was not related to the study objective—i.e., assessing the effects on premature mortality, violent behavior, psychiatric illness, individual traits, and personality; type of article such as narrative review and neuropsychiatry review; and because of our inability to obtain the full article—e.g., forthcoming work in 2021. One qualitative article was added to explain the domain related to risk and the protective factors among the adolescents.