Page Content

Overview of the review report format, the first read-through, first read considerations, spotting potential major flaws, concluding the first reading, rejection after the first reading, before starting the second read-through, doing the second read-through, the second read-through: section by section guidance, how to structure your report, on presentation and style, criticisms & confidential comments to editors, the recommendation, when recommending rejection, additional resources, step by step guide to reviewing a manuscript.

When you receive an invitation to peer review, you should be sent a copy of the paper's abstract to help you decide whether you wish to do the review. Try to respond to invitations promptly - it will prevent delays. It is also important at this stage to declare any potential Conflict of Interest.

The structure of the review report varies between journals. Some follow an informal structure, while others have a more formal approach.

" Number your comments!!! " (Jonathon Halbesleben, former Editor of Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology)

Informal Structure

Many journals don't provide criteria for reviews beyond asking for your 'analysis of merits'. In this case, you may wish to familiarize yourself with examples of other reviews done for the journal, which the editor should be able to provide or, as you gain experience, rely on your own evolving style.

Formal Structure

Other journals require a more formal approach. Sometimes they will ask you to address specific questions in your review via a questionnaire. Or they might want you to rate the manuscript on various attributes using a scorecard. Often you can't see these until you log in to submit your review. So when you agree to the work, it's worth checking for any journal-specific guidelines and requirements. If there are formal guidelines, let them direct the structure of your review.

In Both Cases

Whether specifically required by the reporting format or not, you should expect to compile comments to authors and possibly confidential ones to editors only.

Following the invitation to review, when you'll have received the article abstract, you should already understand the aims, key data and conclusions of the manuscript. If you don't, make a note now that you need to feedback on how to improve those sections.

The first read-through is a skim-read. It will help you form an initial impression of the paper and get a sense of whether your eventual recommendation will be to accept or reject the paper.

Keep a pen and paper handy when skim-reading.

Try to bear in mind the following questions - they'll help you form your overall impression:

- What is the main question addressed by the research? Is it relevant and interesting?

- How original is the topic? What does it add to the subject area compared with other published material?

- Is the paper well written? Is the text clear and easy to read?

- Are the conclusions consistent with the evidence and arguments presented? Do they address the main question posed?

- If the author is disagreeing significantly with the current academic consensus, do they have a substantial case? If not, what would be required to make their case credible?

- If the paper includes tables or figures, what do they add to the paper? Do they aid understanding or are they superfluous?

While you should read the whole paper, making the right choice of what to read first can save time by flagging major problems early on.

Editors say, " Specific recommendations for remedying flaws are VERY welcome ."

Examples of possibly major flaws include:

- Drawing a conclusion that is contradicted by the author's own statistical or qualitative evidence

- The use of a discredited method

- Ignoring a process that is known to have a strong influence on the area under study

If experimental design features prominently in the paper, first check that the methodology is sound - if not, this is likely to be a major flaw.

You might examine:

- The sampling in analytical papers

- The sufficient use of control experiments

- The precision of process data

- The regularity of sampling in time-dependent studies

- The validity of questions, the use of a detailed methodology and the data analysis being done systematically (in qualitative research)

- That qualitative research extends beyond the author's opinions, with sufficient descriptive elements and appropriate quotes from interviews or focus groups

Major Flaws in Information

If methodology is less of an issue, it's often a good idea to look at the data tables, figures or images first. Especially in science research, it's all about the information gathered. If there are critical flaws in this, it's very likely the manuscript will need to be rejected. Such issues include:

- Insufficient data

- Unclear data tables

- Contradictory data that either are not self-consistent or disagree with the conclusions

- Confirmatory data that adds little, if anything, to current understanding - unless strong arguments for such repetition are made

If you find a major problem, note your reasoning and clear supporting evidence (including citations).

After the initial read and using your notes, including those of any major flaws you found, draft the first two paragraphs of your review - the first summarizing the research question addressed and the second the contribution of the work. If the journal has a prescribed reporting format, this draft will still help you compose your thoughts.

The First Paragraph

This should state the main question addressed by the research and summarize the goals, approaches, and conclusions of the paper. It should:

- Help the editor properly contextualize the research and add weight to your judgement

- Show the author what key messages are conveyed to the reader, so they can be sure they are achieving what they set out to do

- Focus on successful aspects of the paper so the author gets a sense of what they've done well

The Second Paragraph

This should provide a conceptual overview of the contribution of the research. So consider:

- Is the paper's premise interesting and important?

- Are the methods used appropriate?

- Do the data support the conclusions?

After drafting these two paragraphs, you should be in a position to decide whether this manuscript is seriously flawed and should be rejected (see the next section). Or whether it is publishable in principle and merits a detailed, careful read through.

Even if you are coming to the opinion that an article has serious flaws, make sure you read the whole paper. This is very important because you may find some really positive aspects that can be communicated to the author. This could help them with future submissions.

A full read-through will also make sure that any initial concerns are indeed correct and fair. After all, you need the context of the whole paper before deciding to reject. If you still intend to recommend rejection, see the section "When recommending rejection."

Once the paper has passed your first read and you've decided the article is publishable in principle, one purpose of the second, detailed read-through is to help prepare the manuscript for publication. You may still decide to recommend rejection following a second reading.

" Offer clear suggestions for how the authors can address the concerns raised. In other words, if you're going to raise a problem, provide a solution ." (Jonathon Halbesleben, Editor of Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology)

Preparation

To save time and simplify the review:

- Don't rely solely upon inserting comments on the manuscript document - make separate notes

- Try to group similar concerns or praise together

- If using a review program to note directly onto the manuscript, still try grouping the concerns and praise in separate notes - it helps later

- Note line numbers of text upon which your notes are based - this helps you find items again and also aids those reading your review

Now that you have completed your preparations, you're ready to spend an hour or so reading carefully through the manuscript.

As you're reading through the manuscript for a second time, you'll need to keep in mind the argument's construction, the clarity of the language and content.

With regard to the argument’s construction, you should identify:

- Any places where the meaning is unclear or ambiguous

- Any factual errors

- Any invalid arguments

You may also wish to consider:

- Does the title properly reflect the subject of the paper?

- Does the abstract provide an accessible summary of the paper?

- Do the keywords accurately reflect the content?

- Is the paper an appropriate length?

- Are the key messages short, accurate and clear?

Not every submission is well written. Part of your role is to make sure that the text’s meaning is clear.

Editors say, " If a manuscript has many English language and editing issues, please do not try and fix it. If it is too bad, note that in your review and it should be up to the authors to have the manuscript edited ."

If the article is difficult to understand, you should have rejected it already. However, if the language is poor but you understand the core message, see if you can suggest improvements to fix the problem:

- Are there certain aspects that could be communicated better, such as parts of the discussion?

- Should the authors consider resubmitting to the same journal after language improvements?

- Would you consider looking at the paper again once these issues are dealt with?

On Grammar and Punctuation

Your primary role is judging the research content. Don't spend time polishing grammar or spelling. Editors will make sure that the text is at a high standard before publication. However, if you spot grammatical errors that affect clarity of meaning, then it's important to highlight these. Expect to suggest such amendments - it's rare for a manuscript to pass review with no corrections.

A 2010 study of nursing journals found that 79% of recommendations by reviewers were influenced by grammar and writing style (Shattel, et al., 2010).

1. The Introduction

A well-written introduction:

- Sets out the argument

- Summarizes recent research related to the topic

- Highlights gaps in current understanding or conflicts in current knowledge

- Establishes the originality of the research aims by demonstrating the need for investigations in the topic area

- Gives a clear idea of the target readership, why the research was carried out and the novelty and topicality of the manuscript

Originality and Topicality

Originality and topicality can only be established in the light of recent authoritative research. For example, it's impossible to argue that there is a conflict in current understanding by referencing articles that are 10 years old.

Authors may make the case that a topic hasn't been investigated in several years and that new research is required. This point is only valid if researchers can point to recent developments in data gathering techniques or to research in indirectly related fields that suggest the topic needs revisiting. Clearly, authors can only do this by referencing recent literature. Obviously, where older research is seminal or where aspects of the methodology rely upon it, then it is perfectly appropriate for authors to cite some older papers.

Editors say, "Is the report providing new information; is it novel or just confirmatory of well-known outcomes ?"

It's common for the introduction to end by stating the research aims. By this point you should already have a good impression of them - if the explicit aims come as a surprise, then the introduction needs improvement.

2. Materials and Methods

Academic research should be replicable, repeatable and robust - and follow best practice.

Replicable Research

This makes sufficient use of:

- Control experiments

- Repeated analyses

- Repeated experiments

These are used to make sure observed trends are not due to chance and that the same experiment could be repeated by other researchers - and result in the same outcome. Statistical analyses will not be sound if methods are not replicable. Where research is not replicable, the paper should be recommended for rejection.

Repeatable Methods

These give enough detail so that other researchers are able to carry out the same research. For example, equipment used or sampling methods should all be described in detail so that others could follow the same steps. Where methods are not detailed enough, it's usual to ask for the methods section to be revised.

Robust Research

This has enough data points to make sure the data are reliable. If there are insufficient data, it might be appropriate to recommend revision. You should also consider whether there is any in-built bias not nullified by the control experiments.

Best Practice

During these checks you should keep in mind best practice:

- Standard guidelines were followed (e.g. the CONSORT Statement for reporting randomized trials)

- The health and safety of all participants in the study was not compromised

- Ethical standards were maintained

If the research fails to reach relevant best practice standards, it's usual to recommend rejection. What's more, you don't then need to read any further.

3. Results and Discussion

This section should tell a coherent story - What happened? What was discovered or confirmed?

Certain patterns of good reporting need to be followed by the author:

- They should start by describing in simple terms what the data show

- They should make reference to statistical analyses, such as significance or goodness of fit

- Once described, they should evaluate the trends observed and explain the significance of the results to wider understanding. This can only be done by referencing published research

- The outcome should be a critical analysis of the data collected

Discussion should always, at some point, gather all the information together into a single whole. Authors should describe and discuss the overall story formed. If there are gaps or inconsistencies in the story, they should address these and suggest ways future research might confirm the findings or take the research forward.

4. Conclusions

This section is usually no more than a few paragraphs and may be presented as part of the results and discussion, or in a separate section. The conclusions should reflect upon the aims - whether they were achieved or not - and, just like the aims, should not be surprising. If the conclusions are not evidence-based, it's appropriate to ask for them to be re-written.

5. Information Gathered: Images, Graphs and Data Tables

If you find yourself looking at a piece of information from which you cannot discern a story, then you should ask for improvements in presentation. This could be an issue with titles, labels, statistical notation or image quality.

Where information is clear, you should check that:

- The results seem plausible, in case there is an error in data gathering

- The trends you can see support the paper's discussion and conclusions

- There are sufficient data. For example, in studies carried out over time are there sufficient data points to support the trends described by the author?

You should also check whether images have been edited or manipulated to emphasize the story they tell. This may be appropriate but only if authors report on how the image has been edited (e.g. by highlighting certain parts of an image). Where you feel that an image has been edited or manipulated without explanation, you should highlight this in a confidential comment to the editor in your report.

6. List of References

You will need to check referencing for accuracy, adequacy and balance.

Where a cited article is central to the author's argument, you should check the accuracy and format of the reference - and bear in mind different subject areas may use citations differently. Otherwise, it's the editor’s role to exhaustively check the reference section for accuracy and format.

You should consider if the referencing is adequate:

- Are important parts of the argument poorly supported?

- Are there published studies that show similar or dissimilar trends that should be discussed?

- If a manuscript only uses half the citations typical in its field, this may be an indicator that referencing should be improved - but don't be guided solely by quantity

- References should be relevant, recent and readily retrievable

Check for a well-balanced list of references that is:

- Helpful to the reader

- Fair to competing authors

- Not over-reliant on self-citation

- Gives due recognition to the initial discoveries and related work that led to the work under assessment

You should be able to evaluate whether the article meets the criteria for balanced referencing without looking up every reference.

7. Plagiarism

By now you will have a deep understanding of the paper's content - and you may have some concerns about plagiarism.

Identified Concern

If you find - or already knew of - a very similar paper, this may be because the author overlooked it in their own literature search. Or it may be because it is very recent or published in a journal slightly outside their usual field.

You may feel you can advise the author how to emphasize the novel aspects of their own study, so as to better differentiate it from similar research. If so, you may ask the author to discuss their aims and results, or modify their conclusions, in light of the similar article. Of course, the research similarities may be so great that they render the work unoriginal and you have no choice but to recommend rejection.

"It's very helpful when a reviewer can point out recent similar publications on the same topic by other groups, or that the authors have already published some data elsewhere ." (Editor feedback)

Suspected Concern

If you suspect plagiarism, including self-plagiarism, but cannot recall or locate exactly what is being plagiarized, notify the editor of your suspicion and ask for guidance.

Most editors have access to software that can check for plagiarism.

Editors are not out to police every paper, but when plagiarism is discovered during peer review it can be properly addressed ahead of publication. If plagiarism is discovered only after publication, the consequences are worse for both authors and readers, because a retraction may be necessary.

For detailed guidelines see COPE's Ethical guidelines for reviewers and Wiley's Best Practice Guidelines on Publishing Ethics .

8. Search Engine Optimization (SEO)

After the detailed read-through, you will be in a position to advise whether the title, abstract and key words are optimized for search purposes. In order to be effective, good SEO terms will reflect the aims of the research.

A clear title and abstract will improve the paper's search engine rankings and will influence whether the user finds and then decides to navigate to the main article. The title should contain the relevant SEO terms early on. This has a major effect on the impact of a paper, since it helps it appear in search results. A poor abstract can then lose the reader's interest and undo the benefit of an effective title - whilst the paper's abstract may appear in search results, the potential reader may go no further.

So ask yourself, while the abstract may have seemed adequate during earlier checks, does it:

- Do justice to the manuscript in this context?

- Highlight important findings sufficiently?

- Present the most interesting data?

Editors say, " Does the Abstract highlight the important findings of the study ?"

If there is a formal report format, remember to follow it. This will often comprise a range of questions followed by comment sections. Try to answer all the questions. They are there because the editor felt that they are important. If you're following an informal report format you could structure your report in three sections: summary, major issues, minor issues.

- Give positive feedback first. Authors are more likely to read your review if you do so. But don't overdo it if you will be recommending rejection

- Briefly summarize what the paper is about and what the findings are

- Try to put the findings of the paper into the context of the existing literature and current knowledge

- Indicate the significance of the work and if it is novel or mainly confirmatory

- Indicate the work's strengths, its quality and completeness

- State any major flaws or weaknesses and note any special considerations. For example, if previously held theories are being overlooked

Major Issues

- Are there any major flaws? State what they are and what the severity of their impact is on the paper

- Has similar work already been published without the authors acknowledging this?

- Are the authors presenting findings that challenge current thinking? Is the evidence they present strong enough to prove their case? Have they cited all the relevant work that would contradict their thinking and addressed it appropriately?

- If major revisions are required, try to indicate clearly what they are

- Are there any major presentational problems? Are figures & tables, language and manuscript structure all clear enough for you to accurately assess the work?

- Are there any ethical issues? If you are unsure it may be better to disclose these in the confidential comments section

Minor Issues

- Are there places where meaning is ambiguous? How can this be corrected?

- Are the correct references cited? If not, which should be cited instead/also? Are citations excessive, limited, or biased?

- Are there any factual, numerical or unit errors? If so, what are they?

- Are all tables and figures appropriate, sufficient, and correctly labelled? If not, say which are not

Your review should ultimately help the author improve their article. So be polite, honest and clear. You should also try to be objective and constructive, not subjective and destructive.

You should also:

- Write clearly and so you can be understood by people whose first language is not English

- Avoid complex or unusual words, especially ones that would even confuse native speakers

- Number your points and refer to page and line numbers in the manuscript when making specific comments

- If you have been asked to only comment on specific parts or aspects of the manuscript, you should indicate clearly which these are

- Treat the author's work the way you would like your own to be treated

Most journals give reviewers the option to provide some confidential comments to editors. Often this is where editors will want reviewers to state their recommendation - see the next section - but otherwise this area is best reserved for communicating malpractice such as suspected plagiarism, fraud, unattributed work, unethical procedures, duplicate publication, bias or other conflicts of interest.

However, this doesn't give reviewers permission to 'backstab' the author. Authors can't see this feedback and are unable to give their side of the story unless the editor asks them to. So in the spirit of fairness, write comments to editors as though authors might read them too.

Reviewers should check the preferences of individual journals as to where they want review decisions to be stated. In particular, bear in mind that some journals will not want the recommendation included in any comments to authors, as this can cause editors difficulty later - see Section 11 for more advice about working with editors.

You will normally be asked to indicate your recommendation (e.g. accept, reject, revise and resubmit, etc.) from a fixed-choice list and then to enter your comments into a separate text box.

Recommending Acceptance

If you're recommending acceptance, give details outlining why, and if there are any areas that could be improved. Don't just give a short, cursory remark such as 'great, accept'. See Improving the Manuscript

Recommending Revision

Where improvements are needed, a recommendation for major or minor revision is typical. You may also choose to state whether you opt in or out of the post-revision review too. If recommending revision, state specific changes you feel need to be made. The author can then reply to each point in turn.

Some journals offer the option to recommend rejection with the possibility of resubmission – this is most relevant where substantial, major revision is necessary.

What can reviewers do to help? " Be clear in their comments to the author (or editor) which points are absolutely critical if the paper is given an opportunity for revisio n." (Jonathon Halbesleben, Editor of Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology)

Recommending Rejection

If recommending rejection or major revision, state this clearly in your review (and see the next section, 'When recommending rejection').

Where manuscripts have serious flaws you should not spend any time polishing the review you've drafted or give detailed advice on presentation.

Editors say, " If a reviewer suggests a rejection, but her/his comments are not detailed or helpful, it does not help the editor in making a decision ."

In your recommendations for the author, you should:

- Give constructive feedback describing ways that they could improve the research

- Keep the focus on the research and not the author. This is an extremely important part of your job as a reviewer

- Avoid making critical confidential comments to the editor while being polite and encouraging to the author - the latter may not understand why their manuscript has been rejected. Also, they won't get feedback on how to improve their research and it could trigger an appeal

Remember to give constructive criticism even if recommending rejection. This helps developing researchers improve their work and explains to the editor why you felt the manuscript should not be published.

" When the comments seem really positive, but the recommendation is rejection…it puts the editor in a tough position of having to reject a paper when the comments make it sound like a great paper ." (Jonathon Halbesleben, Editor of Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology)

Visit our Wiley Author Learning and Training Channel for expert advice on peer review.

Watch the video, Ethical considerations of Peer Review

- YJBM Updates

- Editorial Board

- Colloquium Series

- Podcast Series

- Open Access

- Call for Papers

- PubMed Publications

- News & Views

- Why Publish in YJBM?

- Types of Articles Published

- Manuscript Submission Guidelines

- YJBM Ethical Guidelines

Points to Consider When Reviewing Articles

- Writing and Submitting a Review

- Join Our Peer Reviewer Database

INFORMATION FOR

- Residents & Fellows

- Researchers

General questions that Reviewers should keep in mind when reviewing articles are the following:

- Is the article of interest to the readers of YJBM ?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the manuscript?

- How can the Editors work with the Authors to improve the submitted manuscripts, if the topic and scope of the manuscript is of interest to YJBM readers?

The following contains detailed descriptions as to what should be included in each particular type of article as well as points that Reviewers should keep in mind when specifically reviewing each type of article.

YJBM will ask Reviewers to Peer Review the following types of submissions:

Download PDF

Frequently asked questions.

These manuscripts should present well-rounded studies reporting innovative advances that further knowledge about a topic of importance to the fields of biology or medicine. The conclusions of the Original Research Article should clearly be supported by the results. These can be submitted as either a full-length article (no more than 6,000 words, 8 figures, and 4 tables) or a brief communication (no more than 2,500 words, 3 figures, and 2 tables). Original Research Articles contain five sections: abstract, introduction, materials and methods, results and discussion.

Reviewers should consider the following questions:

- What is the overall aim of the research being presented? Is this clearly stated?

- Have the Authors clearly stated what they have identified in their research?

- Are the aims of the manuscript and the results of the data clearly and concisely stated in the abstract?

- Does the introduction provide sufficient background information to enable readers to better understand the problem being identified by the Authors?

- Have the Authors provided sufficient evidence for the claims they are making? If not, what further experiments or data needs to be included?

- Are similar claims published elsewhere? Have the Authors acknowledged these other publications? Have the Authors made it clear how the data presented in the Author’s manuscript is different or builds upon previously published data?

- Is the data presented of high quality and has it been analyzed correctly? If the analysis is incorrect, what should the Authors do to correct this?

- Do all the figures and tables help the reader better understand the manuscript? If not, which figures or tables should be removed and should anything be presented in their place?

- Is the methodology used presented in a clear and concise manner so that someone else can repeat the same experiments? If not, what further information needs to be provided?

- Do the conclusions match the data being presented?

- Have the Authors discussed the implications of their research in the discussion? Have they presented a balanced survey of the literature and information so their data is put into context?

- Is the manuscript accessible to readers who are not familiar with the topic? If not, what further information should the Authors include to improve the accessibility of their manuscript?

- Are all abbreviations used explained? Does the author use standard scientific abbreviations?

Case reports describe an unusual disease presentation, a new treatment, an unexpected drug interaction, a new diagnostic method, or a difficult diagnosis. Case reports should include relevant positive and negative findings from history, examination and investigation, and can include clinical photographs. Additionally, the Author must make it clear what the case adds to the field of medicine and include an up-to-date review of all previous cases. These articles should be no more than 5,000 words, with no more than 6 figures and 3 tables. Case Reports contain five sections: abstract; introduction; case presentation that includes clinical presentation, observations, test results, and accompanying figures; discussion; and conclusions.

- Does the abstract clearly and concisely state the aim of the case report, the findings of the report, and its implications?

- Does the introduction provide enough details for readers who are not familiar with a particular disease/treatment/drug/diagnostic method to make the report accessible to them?

- Does the manuscript clearly state what the case presentation is and what was observed so that someone can use this description to identify similar symptoms or presentations in another patient?

- Are the figures and tables presented clearly explained and annotated? Do they provide useful information to the reader or can specific figures/tables be omitted and/or replaced by another figure/table?

- Are the data presented accurately analyzed and reported in the text? If not, how can the Author improve on this?

- Do the conclusions match the data presented?

- Does the discussion include information of similar case reports and how this current report will help with treatment of a disease/presentation/use of a particular drug?

Reviews provide a reasoned survey and examination of a particular subject of research in biology or medicine. These can be submitted as a mini-review (less than 2,500 words, 3 figures, and 1 table) or a long review (no more than 6,000 words, 6 figures, and 3 tables). They should include critical assessment of the works cited, explanations of conflicts in the literature, and analysis of the field. The conclusion must discuss in detail the limitations of current knowledge, future directions to be pursued in research, and the overall importance of the topic in medicine or biology. Reviews contain four sections: abstract, introduction, topics (with headings and subheadings), and conclusions and outlook.

- Is the review accessible to readers of YJBM who are not familiar with the topic presented?

- Does the abstract accurately summarize the contents of the review?

- Does the introduction clearly state what the focus of the review will be?

- Are the facts reported in the review accurate?

- Does the Author use the most recent literature available to put together this review?

- Is the review split up under relevant subheadings to make it easier for the readers to access the article?

- Does the Author provide balanced viewpoints on a specific topic if there is debate over the topic in the literature?

- Are the figures or tables included relevant to the review and enable the readers to better understand the manuscript? Are there further figures/tables that could be included?

- Do the conclusions and outlooks outline where further research can be done on the topic?

Perspectives provide a personal view on medical or biomedical topics in a clear narrative voice. Articles can relate personal experiences, historical perspective, or profile people or topics important to medicine and biology. Long perspectives should be no more than 6,000 words and contain no more than 2 tables. Brief opinion pieces should be no more than 2,500 words and contain no more than 2 tables. Perspectives contain four sections: abstract, introduction, topics (with headings and subheadings), and conclusions and outlook.

- Does the abstract accurately and concisely summarize the main points provided in the manuscript?

- Does the introduction provide enough information so that the reader can understand the article if he or she were not familiar with the topic?

- Are there specific areas in which the Author can provide more detail to help the reader better understand the manuscript? Or are there places where the author has provided too much detail that detracts from the main point?

- If necessary, does the Author divide the article into specific topics to help the reader better access the article? If not, how should the Author break up the article under specific topics?

- Do the conclusions follow from the information provided by the Author?

- Does the Author reflect and provide lessons learned from a specific personal experience/historical event/work of a specific person?

Analyses provide an in-depth prospective and informed analysis of a policy, major advance, or historical description of a topic related to biology or medicine. These articles should be no more than 6,000 words with no more than 3 figures and 1 table. Analyses contain four sections: abstract, introduction, topics (with headings and subheadings), and conclusions and outlook.

- Does the abstract accurately summarize the contents of the manuscript?

- Does the introduction provide enough information if the readers are not familiar with the topic being addressed?

- Are there specific areas in which the Author can provide more detail to help the reader better understand the manuscript? Or are there places where the Author has provided too much detail that detracts from the main point?

Profiles describe a notable person in the fields of science or medicine. These articles should contextualize the individual’s contributions to the field at large as well as provide some personal and historical background on the person being described. More specifically, this should be done by describing what was known at the time of the individual’s discovery/contribution and how that finding contributes to the field as it stands today. These pieces should be no more than 5,000 words, with up to 6 figures, and 3 tables. The article should include the following: abstract, introduction, topics (with headings and subheadings), and conclusions.

- Does the Author provide information about the person of interest’s background, i.e., where they are from, where they were educated, etc.?

- Does the Author indicate how the person focused on became interested or involved in the subject that he or she became famous for?

- Does the Author provide information on other people who may have helped the person in his or her achievements?

- Does the Author provide information on the history of the topic before the person became involved?

- Does the Author provide information on how the person’s findings affected the field being discussed?

- Does the introduction provide enough information to the readers, should they not be familiar with the topic being addressed?

Interviews may be presented as either a transcript of an interview with questions and answers or as a personal reflection. If the latter, the Author must indicate that the article is based on an interview given. These pieces should be no more than 5,000 words and contain no more than 3 figures and 2 tables. The articles should include: abstract, introduction, questions and answers clearly indicated by subheadings or topics (with heading and subheadings), and conclusions.

- Does the Author provide relevant information to describe who the person is whom they have chosen to interview?

- Does the Author explain why he or she has chosen the person being interviewed?

- Does the Author explain why he or she has decided to focus on a specific topic in the interview?

- Are the questions relevant? Are there more questions that the Author should have asked? Are there questions that the Author has asked that are not necessary?

- If necessary, does the Author divide the article into specific topics to help the reader better access the article? If not, how should the author break up the article under specific topics?

- Does the Author accurately summarize the contents of the interview as well as specific lesson learned, if relevant, in the conclusions?

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- CAREER FEATURE

- 04 December 2020

- Correction 09 December 2020

How to write a superb literature review

Andy Tay is a freelance writer based in Singapore.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Literature reviews are important resources for scientists. They provide historical context for a field while offering opinions on its future trajectory. Creating them can provide inspiration for one’s own research, as well as some practice in writing. But few scientists are trained in how to write a review — or in what constitutes an excellent one. Even picking the appropriate software to use can be an involved decision (see ‘Tools and techniques’). So Nature asked editors and working scientists with well-cited reviews for their tips.

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-03422-x

Interviews have been edited for length and clarity.

Updates & Corrections

Correction 09 December 2020 : An earlier version of the tables in this article included some incorrect details about the programs Zotero, Endnote and Manubot. These have now been corrected.

Hsing, I.-M., Xu, Y. & Zhao, W. Electroanalysis 19 , 755–768 (2007).

Article Google Scholar

Ledesma, H. A. et al. Nature Nanotechnol. 14 , 645–657 (2019).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Brahlek, M., Koirala, N., Bansal, N. & Oh, S. Solid State Commun. 215–216 , 54–62 (2015).

Choi, Y. & Lee, S. Y. Nature Rev. Chem . https://doi.org/10.1038/s41570-020-00221-w (2020).

Download references

Related Articles

- Research management

Massive Attack’s science-led drive to lower music’s carbon footprint

Career Feature 04 SEP 24

Tales of a migratory marine biologist

Career Feature 28 AUG 24

Nail your tech-industry interviews with these six techniques

Career Column 28 AUG 24

Why I’m committed to breaking the bias in large language models

Career Guide 04 SEP 24

Binning out-of-date chemicals? Somebody think about the carbon!

Correspondence 27 AUG 24

No more hunting for replication studies: crowdsourced database makes them easy to find

Nature Index 27 AUG 24

Publishing nightmare: a researcher’s quest to keep his own work from being plagiarized

News 04 SEP 24

Intellectual property and data privacy: the hidden risks of AI

How can I publish open access when I can’t afford the fees?

Career Feature 02 SEP 24

Postdoctoral Associate- Genetic Epidemiology

Houston, Texas (US)

Baylor College of Medicine (BCM)

NOMIS Foundation ETH Postdoctoral Fellowship

The NOMIS Foundation ETH Fellowship Programme supports postdoctoral researchers at ETH Zurich within the Centre for Origin and Prevalence of Life ...

Zurich, Canton of Zürich (CH)

Centre for Origin and Prevalence of Life at ETH Zurich

13 PhD Positions at Heidelberg University

GRK2727/1 – InCheck Innate Immune Checkpoints in Cancer and Tissue Damage

Heidelberg, Baden-Württemberg (DE) and Mannheim, Baden-Württemberg (DE)

Medical Faculties Mannheim & Heidelberg and DKFZ, Germany

Postdoctoral Associate- Environmental Epidemiology

Open faculty positions at the state key laboratory of brain cognition & brain-inspired intelligence.

The laboratory focuses on understanding the mechanisms of brain intelligence and developing the theory and techniques of brain-inspired intelligence.

Shanghai, China

CAS Center for Excellence in Brain Science and Intelligence Technology (CEBSIT)

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

How to write a good scientific review article

Affiliation.

- 1 The FEBS Journal Editorial Office, Cambridge, UK.

- PMID: 35792782

- DOI: 10.1111/febs.16565

Literature reviews are valuable resources for the scientific community. With research accelerating at an unprecedented speed in recent years and more and more original papers being published, review articles have become increasingly important as a means to keep up to date with developments in a particular area of research. A good review article provides readers with an in-depth understanding of a field and highlights key gaps and challenges to address with future research. Writing a review article also helps to expand the writer's knowledge of their specialist area and to develop their analytical and communication skills, amongst other benefits. Thus, the importance of building review-writing into a scientific career cannot be overstated. In this instalment of The FEBS Journal's Words of Advice series, I provide detailed guidance on planning and writing an informative and engaging literature review.

© 2022 Federation of European Biochemical Societies.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- Rules to be adopted for publishing a scientific paper. Picardi N. Picardi N. Ann Ital Chir. 2016;87:1-3. Ann Ital Chir. 2016. PMID: 28474609

- How to write an original article. Mateu Arrom L, Huguet J, Errando C, Breda A, Palou J. Mateu Arrom L, et al. Actas Urol Esp (Engl Ed). 2018 Nov;42(9):545-550. doi: 10.1016/j.acuro.2018.02.011. Epub 2018 May 18. Actas Urol Esp (Engl Ed). 2018. PMID: 29779648 Review. English, Spanish.

- [Writing a scientific review, advice and recommendations]. Turale S. Turale S. Soins. 2013 Dec;(781):39-43. Soins. 2013. PMID: 24558688 French.

- How to write a research paper. Alexandrov AV. Alexandrov AV. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2004;18(2):135-8. doi: 10.1159/000079266. Epub 2004 Jun 23. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2004. PMID: 15218279 Review.

- How to write a review article. Williamson RC. Williamson RC. Hosp Med. 2001 Dec;62(12):780-2. doi: 10.12968/hosp.2001.62.12.2389. Hosp Med. 2001. PMID: 11810740 Review.

- A scoping review of the methodological approaches used in retrospective chart reviews to validate adverse event rates in administrative data. Connolly A, Kirwan M, Matthews A. Connolly A, et al. Int J Qual Health Care. 2024 May 10;36(2):mzae037. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzae037. Int J Qual Health Care. 2024. PMID: 38662407 Free PMC article. Review.

- Ado-tratuzumab emtansine beyond breast cancer: therapeutic role of targeting other HER2-positive cancers. Zheng Y, Zou J, Sun C, Peng F, Peng C. Zheng Y, et al. Front Mol Biosci. 2023 May 11;10:1165781. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2023.1165781. eCollection 2023. Front Mol Biosci. 2023. PMID: 37251081 Free PMC article. Review.

- Connecting authors with readers: what makes a good review for the Korean Journal of Women Health Nursing. Kim HK. Kim HK. Korean J Women Health Nurs. 2023 Mar;29(1):1-4. doi: 10.4069/kjwhn.2023.02.23. Epub 2023 Mar 31. Korean J Women Health Nurs. 2023. PMID: 37037445 Free PMC article. No abstract available.

- Ketcham C, Crawford J. The impact of review articles. Lab Invest. 2007;87:1174-85. https://doi.org/10.1038/labinvest.3700688

- Muka T, Glisic M, Milic J, Verhoog S, Bohlius J, Bramer W, et al. A 24-step guide on how to design, conduct, and successfully publish a systematic review and meta-analysis in medical research. Eur J Epidemiol. 2020;35:49-60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-019-00576-5

- Tawfik GM, Dila KAS, Mohamed MYF, Tam DNH, Kien ND, Ahmed AM, et al. A step by step guide for conducting a systematic review and meta-analysis with simulation data. Trop Med Health. 2019;47:46. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41182-019-0165-6

- Zimba O, Gasparyan AY. Scientific authorship: a primer for researchers. Reumatologia. 2020;58(6):345-9. https://doi.org/10.5114/reum.2020.101999

- Gasparyan AY, Yessirkepov M, Voronov AA, Maksaev AA, Kitas GD. Article-level metrics. J Korean Med Sci. 2021;36(11):e74.

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources.

- Ovid Technologies, Inc.

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Advance Articles

- Editor's Choice

- CME Reviews

- Best of 2021 collection

- Abbreviated Breast MRI Virtual Collection

- Contrast-enhanced Mammography Collection

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Accepted Papers Resource Guide

- About Journal of Breast Imaging

- About the Society of Breast Imaging

- Guidelines for Reviewers

- Resources for Reviewers and Authors

- Editorial Board

- Advertising Disclaimer

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

- < Previous

A Step-by-Step Guide to Writing a Scientific Review Article

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Manisha Bahl, A Step-by-Step Guide to Writing a Scientific Review Article, Journal of Breast Imaging , Volume 5, Issue 4, July/August 2023, Pages 480–485, https://doi.org/10.1093/jbi/wbad028

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Scientific review articles are comprehensive, focused reviews of the scientific literature written by subject matter experts. The task of writing a scientific review article can seem overwhelming; however, it can be managed by using an organized approach and devoting sufficient time to the process. The process involves selecting a topic about which the authors are knowledgeable and enthusiastic, conducting a literature search and critical analysis of the literature, and writing the article, which is composed of an abstract, introduction, body, and conclusion, with accompanying tables and figures. This article, which focuses on the narrative or traditional literature review, is intended to serve as a guide with practical steps for new writers. Tips for success are also discussed, including selecting a focused topic, maintaining objectivity and balance while writing, avoiding tedious data presentation in a laundry list format, moving from descriptions of the literature to critical analysis, avoiding simplistic conclusions, and budgeting time for the overall process.

- narrative discourse

Society of Breast Imaging members

Personal account.

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Short-term Access

To purchase short-term access, please sign in to your personal account above.

Don't already have a personal account? Register

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| May 2023 | 171 |

| June 2023 | 115 |

| July 2023 | 113 |

| August 2023 | 5,013 |

| September 2023 | 1,500 |

| October 2023 | 1,810 |

| November 2023 | 3,849 |

| December 2023 | 308 |

| January 2024 | 401 |

| February 2024 | 312 |

| March 2024 | 415 |

| April 2024 | 361 |

| May 2024 | 306 |

| June 2024 | 283 |

| July 2024 | 309 |

| August 2024 | 243 |

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Librarian

- Journals Career Network

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 2631-6129

- Print ISSN 2631-6110

- Copyright © 2024 Society of Breast Imaging

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

Don't submit your assignments before you do this

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students. Free citation check included.

Try for free

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, September 11). How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved September 3, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

Website maintenance is scheduled for Saturday, September 7, and Sunday, September 8. Short disruptions may occur during these days.

The “PP-ICONS” approach will help you separate the clinical wheat from the chaff in mere minutes .

ROBERT J. FLAHERTY, MD

Fam Pract Manag. 2004;11(5):47-52

Keeping up with the latest advances in diagnosis and treatment is a challenge we all face as phycians. We need information that is both valid (that is, accurate and correct) and relevant to our patients and practices. While we have many sources of clinical information, such as CME lectures, textbooks, pharmaceutical advertising, pharmaceutical representatives and colleagues, we often turn to journal articles for the most current clinical information.

Unfortunately, a great deal of research reported in journal articles is poorly done, poorly analyzed or both, and thus is not valid. A great deal of research is also irrelevant to our patients and practices. Separating the clinical wheat from the chaff can take skills that many of us never were taught.

Reading the abstract is often sufficient when evaluating an article using the PP-ICONS approach.

The most relevant studies will involve outcomes that matter to patients (e.g., morbidity, mortality and cost) versus outcomes that matter to physiologists (e.g., blood pressure, blood sugar or cholesterol levels).

Ignore the relative risk reduction, as it overstates research findings and will mislead you.

The article “Making Evidence-Based Medicine Doable in Everyday Practice” in the February 2004 issue of FPM describes several organizations that can help us. These organizations, such as the Cochrane Library, Bandolier and Clinical Evidence, develop clinical questions and then review one or more journal articles to identify the best available evidence that answers the question, with a focus on the quality of the study, the validity of the results and the relevance of the findings to everyday practice. These organizations provide a very valuable service, and the number of important clinical questions that they have studied has grown steadily over the past five years. (See “Four steps to an evidence-based answer.” )

FOUR STEPS TO AN EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER

When faced with a clinical question, follow these steps to find an evidence-based answer:

Search the Web site of one of the evidence review organizations, such as Cochrane (http://www.cochrane.org/cochrane/revabstr/mainindex.htm), Bandolier ( http://www.jr2.ox.ac.uk/bandolier ) or Clinical Evidence ( http://www.clinicalevidence.com ), described in “Making Evidence-Based Medicine Doable in Everyday Practice,” FPM, February 2004, page 51 . You can also search the TRIP+ Web site ( http://www.tripdatabase.com ), which simultaneously searches the databases of many of the review organizations. If you find a systematic review or meta-analysis by one of these organizations, you can be confident that you’ve found the best evidence available.

If you don’t find the information you need through step 1, search for meta-analyses and systematic reviews using the PubMed Web site (see the tutorial at http://www.nlm.nih.gov/bsd/pubmed_tutorial/m1001.html ). Most of the recent abstracts found on PubMed provide enough information for you to determine the validity and relevance of the findings. If needed, you can get a copy of the full article through your hospital library or the journal’s Web site.

If you cannot find a systematic review or meta-analysis on PubMed, look for a randomized controlled trial (RCT). The RCT is the “gold standard” in medical research. Case reports, cohort studies and other research methods simply are not good enough to use for making patient care decisions.

Once you find the article you need, use the PP-ICONS approach to evaluate its usefulness to your patient.

If you find a systematic review or meta-analysis done by one of these organizations, you can feel confident that you have found the current best evidence. However, these organizations have not asked all of the common clinical questions yet, and you will frequently be faced with finding the pertinent articles and determining for yourself whether they are valuable. This is where the PP-ICONS approach can help.

What is PP-ICONS?

When you find a systematic review, meta-analysis or randomized controlled trial while reading your clinical journals or searching PubMed ( http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi ), you need to determine whether it is valid and relevant. There are many different ways to analyze an abstract or journal article, some more rigorous than others. 1 , 2 I have found a simple but effective way to identify a valid or relevant article within a couple of minutes, ensuring that I can use or discard the conclusions with confidence. This approach works well on articles regarding treatment and prevention, and can also be used with articles on diagnosis and screening.

The most important information to look for when reviewing an article can be summarized by the acronym “PP-ICONS,” which stands for the following:

Patient or population,

Intervention,

Comparison,

Number of subjects,

Statistics.

For example, imagine that you just saw a nine-year-old patient in the office with common warts on her hands, an ideal candidate for your usual cryotherapy. Her mother had heard about treating warts with duct tape and wondered if you would recommend this treatment. You promised to call Mom back after you had a chance to investigate this rather odd treatment.

When you get a free moment, you write down your clinical question: “Is duct tape an effective treatment for warts in children?” Writing down your clinical question is useful, as it can help you clarify exactly what you are looking for. Use the PPICO parts of the acronym to help you write your clinical question; this is actually how many researchers develop their research questions.

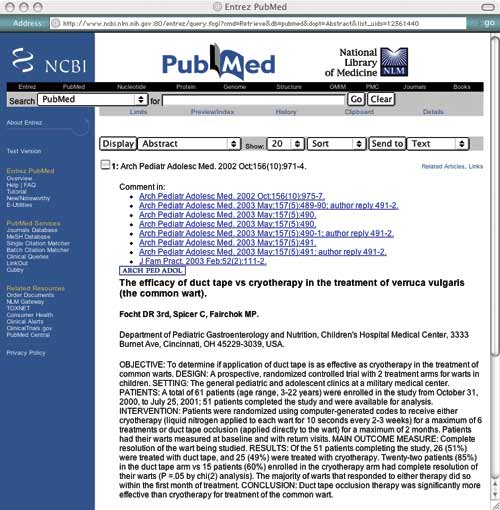

You search Cochrane and Bandolier without success, so now you search PubMed, which returns an abstract for the following article: “Focht DR 3rd, Spicer C, Fairchok MP. The efficacy of duct tape vs cryotherapy in the treatment of verruca vulgaris (the common wart). Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med . 2002 Oct;156(10):971-974.”

You decide to apply PP-ICONS to this abstract (see "Abstract from PubMed" ) to determine if the information is both valid and relevant.

ABSTRACT FROM PUBMED

Using the PP-ICONS approach, physicians can evaluate the validity and relevance of clinical articles in minutes using only the abstract, such as this one, obtained free online from PubMed, http://www.ncbi. nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi. The author uses this abstract to evaluate the use of duct tape to treat common warts.

Problem. The first P in PP-ICONS is for “problem,” which refers to the clinical condition that was studied. From the abstract, it is clear that the researchers studied the same problem you are interested in, which is important since flat warts or genital warts may have responded differently. Obviously, if the problem studied were not sufficiently similar to your clinical problem, the results would not be relevant.