Classroom Q&A

With larry ferlazzo.

In this EdWeek blog, an experiment in knowledge-gathering, Ferlazzo will address readers’ questions on classroom management, ELL instruction, lesson planning, and other issues facing teachers. Send your questions to [email protected]. Read more from this blog.

Eight Instructional Strategies for Promoting Critical Thinking

- Share article

(This is the first post in a three-part series.)

The new question-of-the-week is:

What is critical thinking and how can we integrate it into the classroom?

This three-part series will explore what critical thinking is, if it can be specifically taught and, if so, how can teachers do so in their classrooms.

Today’s guests are Dara Laws Savage, Patrick Brown, Meg Riordan, Ph.D., and Dr. PJ Caposey. Dara, Patrick, and Meg were also guests on my 10-minute BAM! Radio Show . You can also find a list of, and links to, previous shows here.

You might also be interested in The Best Resources On Teaching & Learning Critical Thinking In The Classroom .

Current Events

Dara Laws Savage is an English teacher at the Early College High School at Delaware State University, where she serves as a teacher and instructional coach and lead mentor. Dara has been teaching for 25 years (career preparation, English, photography, yearbook, newspaper, and graphic design) and has presented nationally on project-based learning and technology integration:

There is so much going on right now and there is an overload of information for us to process. Did you ever stop to think how our students are processing current events? They see news feeds, hear news reports, and scan photos and posts, but are they truly thinking about what they are hearing and seeing?

I tell my students that my job is not to give them answers but to teach them how to think about what they read and hear. So what is critical thinking and how can we integrate it into the classroom? There are just as many definitions of critical thinking as there are people trying to define it. However, the Critical Think Consortium focuses on the tools to create a thinking-based classroom rather than a definition: “Shape the climate to support thinking, create opportunities for thinking, build capacity to think, provide guidance to inform thinking.” Using these four criteria and pairing them with current events, teachers easily create learning spaces that thrive on thinking and keep students engaged.

One successful technique I use is the FIRE Write. Students are given a quote, a paragraph, an excerpt, or a photo from the headlines. Students are asked to F ocus and respond to the selection for three minutes. Next, students are asked to I dentify a phrase or section of the photo and write for two minutes. Third, students are asked to R eframe their response around a specific word, phrase, or section within their previous selection. Finally, students E xchange their thoughts with a classmate. Within the exchange, students also talk about how the selection connects to what we are covering in class.

There was a controversial Pepsi ad in 2017 involving Kylie Jenner and a protest with a police presence. The imagery in the photo was strikingly similar to a photo that went viral with a young lady standing opposite a police line. Using that image from a current event engaged my students and gave them the opportunity to critically think about events of the time.

Here are the two photos and a student response:

F - Focus on both photos and respond for three minutes

In the first picture, you see a strong and courageous black female, bravely standing in front of two officers in protest. She is risking her life to do so. Iesha Evans is simply proving to the world she does NOT mean less because she is black … and yet officers are there to stop her. She did not step down. In the picture below, you see Kendall Jenner handing a police officer a Pepsi. Maybe this wouldn’t be a big deal, except this was Pepsi’s weak, pathetic, and outrageous excuse of a commercial that belittles the whole movement of people fighting for their lives.

I - Identify a word or phrase, underline it, then write about it for two minutes

A white, privileged female in place of a fighting black woman was asking for trouble. A struggle we are continuously fighting every day, and they make a mockery of it. “I know what will work! Here Mr. Police Officer! Drink some Pepsi!” As if. Pepsi made a fool of themselves, and now their already dwindling fan base continues to ever shrink smaller.

R - Reframe your thoughts by choosing a different word, then write about that for one minute

You don’t know privilege until it’s gone. You don’t know privilege while it’s there—but you can and will be made accountable and aware. Don’t use it for evil. You are not stupid. Use it to do something. Kendall could’ve NOT done the commercial. Kendall could’ve released another commercial standing behind a black woman. Anything!

Exchange - Remember to discuss how this connects to our school song project and our previous discussions?

This connects two ways - 1) We want to convey a strong message. Be powerful. Show who we are. And Pepsi definitely tried. … Which leads to the second connection. 2) Not mess up and offend anyone, as had the one alma mater had been linked to black minstrels. We want to be amazing, but we have to be smart and careful and make sure we include everyone who goes to our school and everyone who may go to our school.

As a final step, students read and annotate the full article and compare it to their initial response.

Using current events and critical-thinking strategies like FIRE writing helps create a learning space where thinking is the goal rather than a score on a multiple-choice assessment. Critical-thinking skills can cross over to any of students’ other courses and into life outside the classroom. After all, we as teachers want to help the whole student be successful, and critical thinking is an important part of navigating life after they leave our classrooms.

‘Before-Explore-Explain’

Patrick Brown is the executive director of STEM and CTE for the Fort Zumwalt school district in Missouri and an experienced educator and author :

Planning for critical thinking focuses on teaching the most crucial science concepts, practices, and logical-thinking skills as well as the best use of instructional time. One way to ensure that lessons maintain a focus on critical thinking is to focus on the instructional sequence used to teach.

Explore-before-explain teaching is all about promoting critical thinking for learners to better prepare students for the reality of their world. What having an explore-before-explain mindset means is that in our planning, we prioritize giving students firsthand experiences with data, allow students to construct evidence-based claims that focus on conceptual understanding, and challenge students to discuss and think about the why behind phenomena.

Just think of the critical thinking that has to occur for students to construct a scientific claim. 1) They need the opportunity to collect data, analyze it, and determine how to make sense of what the data may mean. 2) With data in hand, students can begin thinking about the validity and reliability of their experience and information collected. 3) They can consider what differences, if any, they might have if they completed the investigation again. 4) They can scrutinize outlying data points for they may be an artifact of a true difference that merits further exploration of a misstep in the procedure, measuring device, or measurement. All of these intellectual activities help them form more robust understanding and are evidence of their critical thinking.

In explore-before-explain teaching, all of these hard critical-thinking tasks come before teacher explanations of content. Whether we use discovery experiences, problem-based learning, and or inquiry-based activities, strategies that are geared toward helping students construct understanding promote critical thinking because students learn content by doing the practices valued in the field to generate knowledge.

An Issue of Equity

Meg Riordan, Ph.D., is the chief learning officer at The Possible Project, an out-of-school program that collaborates with youth to build entrepreneurial skills and mindsets and provides pathways to careers and long-term economic prosperity. She has been in the field of education for over 25 years as a middle and high school teacher, school coach, college professor, regional director of N.Y.C. Outward Bound Schools, and director of external research with EL Education:

Although critical thinking often defies straightforward definition, most in the education field agree it consists of several components: reasoning, problem-solving, and decisionmaking, plus analysis and evaluation of information, such that multiple sides of an issue can be explored. It also includes dispositions and “the willingness to apply critical-thinking principles, rather than fall back on existing unexamined beliefs, or simply believe what you’re told by authority figures.”

Despite variation in definitions, critical thinking is nonetheless promoted as an essential outcome of students’ learning—we want to see students and adults demonstrate it across all fields, professions, and in their personal lives. Yet there is simultaneously a rationing of opportunities in schools for students of color, students from under-resourced communities, and other historically marginalized groups to deeply learn and practice critical thinking.

For example, many of our most underserved students often spend class time filling out worksheets, promoting high compliance but low engagement, inquiry, critical thinking, or creation of new ideas. At a time in our world when college and careers are critical for participation in society and the global, knowledge-based economy, far too many students struggle within classrooms and schools that reinforce low-expectations and inequity.

If educators aim to prepare all students for an ever-evolving marketplace and develop skills that will be valued no matter what tomorrow’s jobs are, then we must move critical thinking to the forefront of classroom experiences. And educators must design learning to cultivate it.

So, what does that really look like?

Unpack and define critical thinking

To understand critical thinking, educators need to first unpack and define its components. What exactly are we looking for when we speak about reasoning or exploring multiple perspectives on an issue? How does problem-solving show up in English, math, science, art, or other disciplines—and how is it assessed? At Two Rivers, an EL Education school, the faculty identified five constructs of critical thinking, defined each, and created rubrics to generate a shared picture of quality for teachers and students. The rubrics were then adapted across grade levels to indicate students’ learning progressions.

At Avenues World School, critical thinking is one of the Avenues World Elements and is an enduring outcome embedded in students’ early experiences through 12th grade. For instance, a kindergarten student may be expected to “identify cause and effect in familiar contexts,” while an 8th grader should demonstrate the ability to “seek out sufficient evidence before accepting a claim as true,” “identify bias in claims and evidence,” and “reconsider strongly held points of view in light of new evidence.”

When faculty and students embrace a common vision of what critical thinking looks and sounds like and how it is assessed, educators can then explicitly design learning experiences that call for students to employ critical-thinking skills. This kind of work must occur across all schools and programs, especially those serving large numbers of students of color. As Linda Darling-Hammond asserts , “Schools that serve large numbers of students of color are least likely to offer the kind of curriculum needed to ... help students attain the [critical-thinking] skills needed in a knowledge work economy. ”

So, what can it look like to create those kinds of learning experiences?

Designing experiences for critical thinking

After defining a shared understanding of “what” critical thinking is and “how” it shows up across multiple disciplines and grade levels, it is essential to create learning experiences that impel students to cultivate, practice, and apply these skills. There are several levers that offer pathways for teachers to promote critical thinking in lessons:

1.Choose Compelling Topics: Keep it relevant

A key Common Core State Standard asks for students to “write arguments to support claims in an analysis of substantive topics or texts using valid reasoning and relevant and sufficient evidence.” That might not sound exciting or culturally relevant. But a learning experience designed for a 12th grade humanities class engaged learners in a compelling topic— policing in America —to analyze and evaluate multiple texts (including primary sources) and share the reasoning for their perspectives through discussion and writing. Students grappled with ideas and their beliefs and employed deep critical-thinking skills to develop arguments for their claims. Embedding critical-thinking skills in curriculum that students care about and connect with can ignite powerful learning experiences.

2. Make Local Connections: Keep it real

At The Possible Project , an out-of-school-time program designed to promote entrepreneurial skills and mindsets, students in a recent summer online program (modified from in-person due to COVID-19) explored the impact of COVID-19 on their communities and local BIPOC-owned businesses. They learned interviewing skills through a partnership with Everyday Boston , conducted virtual interviews with entrepreneurs, evaluated information from their interviews and local data, and examined their previously held beliefs. They created blog posts and videos to reflect on their learning and consider how their mindsets had changed as a result of the experience. In this way, we can design powerful community-based learning and invite students into productive struggle with multiple perspectives.

3. Create Authentic Projects: Keep it rigorous

At Big Picture Learning schools, students engage in internship-based learning experiences as a central part of their schooling. Their school-based adviser and internship-based mentor support them in developing real-world projects that promote deeper learning and critical-thinking skills. Such authentic experiences teach “young people to be thinkers, to be curious, to get from curiosity to creation … and it helps students design a learning experience that answers their questions, [providing an] opportunity to communicate it to a larger audience—a major indicator of postsecondary success.” Even in a remote environment, we can design projects that ask more of students than rote memorization and that spark critical thinking.

Our call to action is this: As educators, we need to make opportunities for critical thinking available not only to the affluent or those fortunate enough to be placed in advanced courses. The tools are available, let’s use them. Let’s interrogate our current curriculum and design learning experiences that engage all students in real, relevant, and rigorous experiences that require critical thinking and prepare them for promising postsecondary pathways.

Critical Thinking & Student Engagement

Dr. PJ Caposey is an award-winning educator, keynote speaker, consultant, and author of seven books who currently serves as the superintendent of schools for the award-winning Meridian CUSD 223 in northwest Illinois. You can find PJ on most social-media platforms as MCUSDSupe:

When I start my keynote on student engagement, I invite two people up on stage and give them each five paper balls to shoot at a garbage can also conveniently placed on stage. Contestant One shoots their shot, and the audience gives approval. Four out of 5 is a heckuva score. Then just before Contestant Two shoots, I blindfold them and start moving the garbage can back and forth. I usually try to ensure that they can at least make one of their shots. Nobody is successful in this unfair environment.

I thank them and send them back to their seats and then explain that this little activity was akin to student engagement. While we all know we want student engagement, we are shooting at different targets. More importantly, for teachers, it is near impossible for them to hit a target that is moving and that they cannot see.

Within the world of education and particularly as educational leaders, we have failed to simplify what student engagement looks like, and it is impossible to define or articulate what student engagement looks like if we cannot clearly articulate what critical thinking is and looks like in a classroom. Because, simply, without critical thought, there is no engagement.

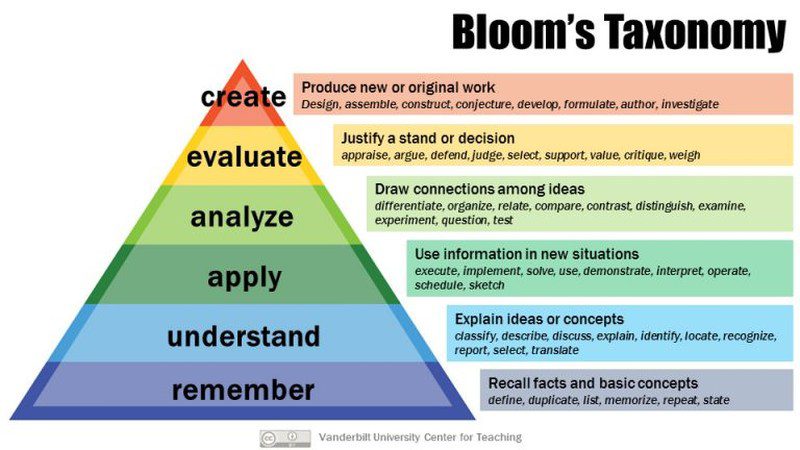

The good news here is that critical thought has been defined and placed into taxonomies for decades already. This is not something new and not something that needs to be redefined. I am a Bloom’s person, but there is nothing wrong with DOK or some of the other taxonomies, either. To be precise, I am a huge fan of Daggett’s Rigor and Relevance Framework. I have used that as a core element of my practice for years, and it has shaped who I am as an instructional leader.

So, in order to explain critical thought, a teacher or a leader must familiarize themselves with these tried and true taxonomies. Easy, right? Yes, sort of. The issue is not understanding what critical thought is; it is the ability to integrate it into the classrooms. In order to do so, there are a four key steps every educator must take.

- Integrating critical thought/rigor into a lesson does not happen by chance, it happens by design. Planning for critical thought and engagement is much different from planning for a traditional lesson. In order to plan for kids to think critically, you have to provide a base of knowledge and excellent prompts to allow them to explore their own thinking in order to analyze, evaluate, or synthesize information.

- SIDE NOTE – Bloom’s verbs are a great way to start when writing objectives, but true planning will take you deeper than this.

QUESTIONING

- If the questions and prompts given in a classroom have correct answers or if the teacher ends up answering their own questions, the lesson will lack critical thought and rigor.

- Script five questions forcing higher-order thought prior to every lesson. Experienced teachers may not feel they need this, but it helps to create an effective habit.

- If lessons are rigorous and assessments are not, students will do well on their assessments, and that may not be an accurate representation of the knowledge and skills they have mastered. If lessons are easy and assessments are rigorous, the exact opposite will happen. When deciding to increase critical thought, it must happen in all three phases of the game: planning, instruction, and assessment.

TALK TIME / CONTROL

- To increase rigor, the teacher must DO LESS. This feels counterintuitive but is accurate. Rigorous lessons involving tons of critical thought must allow for students to work on their own, collaborate with peers, and connect their ideas. This cannot happen in a silent room except for the teacher talking. In order to increase rigor, decrease talk time and become comfortable with less control. Asking questions and giving prompts that lead to no true correct answer also means less control. This is a tough ask for some teachers. Explained differently, if you assign one assignment and get 30 very similar products, you have most likely assigned a low-rigor recipe. If you assign one assignment and get multiple varied products, then the students have had a chance to think deeply, and you have successfully integrated critical thought into your classroom.

Thanks to Dara, Patrick, Meg, and PJ for their contributions!

Please feel free to leave a comment with your reactions to the topic or directly to anything that has been said in this post.

Consider contributing a question to be answered in a future post. You can send one to me at [email protected] . When you send it in, let me know if I can use your real name if it’s selected or if you’d prefer remaining anonymous and have a pseudonym in mind.

You can also contact me on Twitter at @Larryferlazzo .

Education Week has published a collection of posts from this blog, along with new material, in an e-book form. It’s titled Classroom Management Q&As: Expert Strategies for Teaching .

Just a reminder; you can subscribe and receive updates from this blog via email (The RSS feed for this blog, and for all Ed Week articles, has been changed by the new redesign—new ones won’t be available until February). And if you missed any of the highlights from the first nine years of this blog, you can see a categorized list below.

- This Year’s Most Popular Q&A Posts

- Race & Racism in Schools

- School Closures & the Coronavirus Crisis

- Classroom-Management Advice

- Best Ways to Begin the School Year

- Best Ways to End the School Year

- Student Motivation & Social-Emotional Learning

- Implementing the Common Core

- Facing Gender Challenges in Education

- Teaching Social Studies

- Cooperative & Collaborative Learning

- Using Tech in the Classroom

- Student Voices

- Parent Engagement in Schools

- Teaching English-Language Learners

- Reading Instruction

- Writing Instruction

- Education Policy Issues

- Differentiating Instruction

- Math Instruction

- Science Instruction

- Advice for New Teachers

- Author Interviews

- Entering the Teaching Profession

- The Inclusive Classroom

- Learning & the Brain

- Administrator Leadership

- Teacher Leadership

- Relationships in Schools

- Professional Development

- Instructional Strategies

- Best of Classroom Q&A

- Professional Collaboration

- Classroom Organization

- Mistakes in Education

- Project-Based Learning

I am also creating a Twitter list including all contributors to this column .

The opinions expressed in Classroom Q&A With Larry Ferlazzo are strictly those of the author(s) and do not reflect the opinions or endorsement of Editorial Projects in Education, or any of its publications.

Sign Up for EdWeek Update

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

6 Ways to Teach Critical Thinking

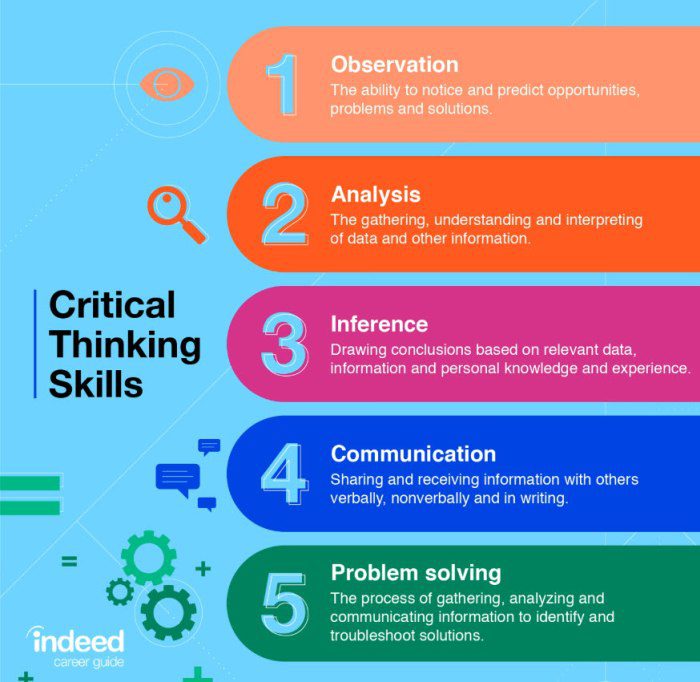

Critical thinking is an essential cognitive process that involves actively analyzing, evaluating, and synthesizing information to form reasoned judgments and solve problems. John Dewey defined reflective thinking as the careful and deliberate determination of whether to accept, reject, or suspend judgment about a claim.

Critical thinking skills include conceptualization, analysis, evaluation, reasoning, synthesis, problem-solving, and openness to new ideas, fostering the ability to discern misinformation, eliminate bias, think independently, and make informed decisions. Thinking critically is vital for personal growth and career advancement. Find out how to develop and teach critical thinking to both adults and children.

Table of Contents

What is critical thinking?

Critical thinking is a set of skills and habits of mind to go beyond simply accepting information or ideas, but instead analyze the issue, evaluate information, and reason critically to make a conclusion or solve a problem. Thinking critically includes making creative connections between ideas from different disciplines.

American philosopher, psychologist, and educator John Dewey (1859–1952) called this “reflective thinking”. Dewey defined critical thinking as active, persistent, and careful consideration of a belief or supposed form of knowledge. It involves actively subjecting ideas to critical scrutiny rather than passively accepting their face value.

What are critical thinking skills?

Here are 7 core critical thinking skills.

- Conceptualize : Form abstract ideas and mental models that accurately represent complex concepts.

- Analyze : Break down information into components and relationships to uncover patterns, principles, and deeper meanings.

- Evaluate : Assess the credibility, accuracy, quality, strength, methodologies, and relevance of claims or evidence using logical standards to judge the validity or significance of the information.

- Reason : Applying logical thinking to conclude from facts or evidence.

- Synthesize : Combining different ideas, findings, or information to form a coherent whole or a new perspective.

- Solve problems : Identifying solutions to issues through logical analysis and creative thinking.

- Open to other possibilities : Being willing to consider alternative solutions, ideas, or viewpoints beyond the initial scope.

Why is critical thinking important?

Critical thinking is an important part of cognitive development for the following 8 reasons.

- Discern misinformation : Critical thinking helps us separate facts from opinions, spot flawed arguments, and avoid falling for inaccurate information.

- Identify and eliminate prejudice : It allows us to recognize societal biases and close-mindedness.

- Think independently : It enables us to develop rational viewpoints rather than blindly accepting claims, mainstream narratives, or fads. It also helps children form their own opinions, make wise decisions, and resist peer pressure.

- Make good decisions : It enables logical thinking for better judgment and making rational decisions, not influenced by emotions.

- Communicate clearly : It lets us understand others’ perspectives and improve communication.

- Get better solutions : It broadens our thought process and enables good problem-solving to achieve the best solutions to challenges.

- Cultivate open-mindedness and creativity : It spurs intellectual curiosity to explore new paradigms.

- Grow skills set : It facilitates wiser, more informed choices that affect personal growth, career advancement, and positive relationships.

Why is critical thinking hard to teach?

Critical thinking is hard to teach because to think critically on a topic, deep knowledge about a subject is required to apply logic. Therefore, critical thinking skills are hard to teach by itself. The analytical reasoning skills learned on one topic don’t transfer quickly to another domain.

What are examples of critical thinking?

Here are examples of critical thinking in real life.

- Solving a math problem : Breaking down complex math problems into smaller parts to understand and solve them step by step.

- Deciding on a book for a report : Reading summaries and reviews to select a book that fits the assignment criteria and personal interest.

- Resolving a dispute with a friend : Listening to each other’s perspectives, identifying the problem, and coming up with a fair solution together.

- Navigating social media safely : Assessing the credibility of online information and the safety of sharing personal data.

- Saving up for a toy : Comparing prices, setting a realistic goal, budgeting allowance money, and resisting impulse buys that derail the plan.

- Figuring out a new bike route : Studying maps for safe streets, estimating distances, choosing the most efficient way, and accounting for hills and traffic.

- Analyzing the motive of a storybook villain : Looking at their actions closely to infer their motivations and thinking through alternative perspectives.

How to develop critical thinking

To develop critical thinking, here are 10 ways to practice.

- Ask probing questions : Ask “why”, “how”, “what if” to deeply understand issues and reveal assumptions.

- Examine evidence objectively : Analyze information’s relevance, credibility, and adequacy.

- Consider different viewpoints : Think through other valid viewpoints that may differ from your own.

- Identify and challenge assumptions : Don’t just accept claims at face value.

- Analyze arguments : Break down arguments and claims into premises and conclusions, and look for logical fallacies.

- Apply reasoned analysis : Base conclusions on logical reasoning and evidence rather than emotion or anecdotes.

- Seek clarity : Ask for explanations of unfamiliar terms and avoid ambiguous claims.

- Discuss ideas : Share your ideas with others to gain insights and refine your thought processes.

- Debate respectfully : Engage in discussions with those who disagree thoughtfully and respectfully.

- Reflect on your thoughts and decisions : Question your thoughts and conclusions to avoid jumping to conclusions.

How to teach critical thinking to a child

To teach critical thinking to a child, encourage them to apply deeper thinking in any situation that requires decision-making in daily life. Here are 6 tips on teaching critical thinking.

- Start early and explain everything : Young children often ask lots of questions. Instead of saying, “That’s how it’s supposed to be,” explain things to them as much as possible from an early age. When children are taught from a young age how to ask different types of questions and formulate judgments using objective evidence and logical analysis, they grow up confident in their ability to question assumptions and reason with logic rather than emotions. When you can’t answer specific questions, you can say, “That’s a good question, and I want to know the answer, too!”

- Prioritize reasoned rules over blind obedience : Authoritarian discipline stifles critical thinking, as demonstrated by psychologist Stanley Milgram’s 1963 study titled “Behavioral Study of Obedience.” In the study, most subjects, under authoritative orders, would administer electric shocks to a stranger and escalate to potentially lethal levels without questioning the authority. Avoid using “because I said so.” Encourage children to inquire, discuss, and participate in rule-making. Help them understand the reasons behind rules to foster critical thinking. Allow children to question and discuss the legitimacy of what we say.

- Encourage problem-solving activities : Encourage your child to solve puzzles, play strategy games, or take on complex problems to strengthen their analytical skills.

- Foster curiosity : Thinking critically means being willing to have your views challenged by new information and different perspectives. Curiosity drives children to explore and question the world around them, challenging assumptions and leading to a deeper understanding of complex concepts.

- Teach open-mindedness : Keeping an open mind and flexible thinking when approaching a new problem is essential in critical thinking. Suggest different points of view, alternative explanations, or solutions to problems. Encourage children to solve problems in new ways and connect different ideas from other domains to strengthen their analytical thinking skills.

- Explain the difference between correlation and causation : One of the biggest impediments to logical reasoning is the confusion between correlation and causation. When two things happen together, they are correlated, but it doesn’t necessarily mean one causes the other. We don’t know whether it’s causation or correlation unless we have more information to prove that.

References For Critical Thinking

- 1. Willingham DT. Critical Thinking: Why Is It So Hard to Teach? Arts Education Policy Review . Published online March 2008:21-32. doi:https://doi.org/10.3200/aepr.109.4.21-32

- 2. Quinn V. Critical Thinking in Young Minds . Routledge; 2018. doi:https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429445323

- 3. Hess RD, McDevitt TM. Some Cognitive Consequences of Maternal Intervention Techniques: A Longitudinal Study. Child Development . Published online December 1984:2017. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/1129776

- 4. Slater M, Antley A, Davison A, et al. A Virtual Reprise of the Stanley Milgram Obedience Experiments. Rustichini A, ed. PLoS ONE . Published online December 20, 2006:e39. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0000039

- 5. Rimiene V. Assessing and Developing Students’ Critical Thinking. Psychology Learning & Teaching . Published online March 2002:17-22. doi:https://doi.org/10.2304/plat.2002.2.1.17

- 6. Dyche L, Epstein RM. Curiosity and medical education. Medical Education . Published online June 7, 2011:663-668. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.03944.x

- 7. Schwartz S. The fallacy of the ecological fallacy: the potential misuse of a concept and the consequences. Am J Public Health . Published online May 1994:819-824. doi:https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.84.5.819

Disclaimer: The content of this article is intended for informational purposes only and should not be considered medical advice. Always consult your healthcare provider for medical concerns.

The Will to Teach

Critical Thinking in the Classroom: A Guide for Teachers

In the ever-evolving landscape of education, teaching students the skill of critical thinking has become a priority. This powerful tool empowers students to evaluate information, make reasoned judgments, and approach problems from a fresh perspective. In this article, we’ll explore the significance of critical thinking and provide effective strategies to nurture this skill in your students.

Why is Fostering Critical Thinking Important?

Strategies to cultivate critical thinking, real-world example, concluding thoughts.

Critical thinking is a key skill that goes far beyond the four walls of a classroom. It equips students to better understand and interact with the world around them. Here are some reasons why fostering critical thinking is important:

- Making Informed Decisions: Critical thinking enables students to evaluate the pros and cons of a situation, helping them make informed and rational decisions.

- Developing Analytical Skills: Critical thinking involves analyzing information from different angles, which enhances analytical skills.

- Promoting Independence: Critical thinking fosters independence by encouraging students to form their own opinions based on their analysis, rather than relying on others.

Creating an environment that encourages critical thinking can be accomplished in various ways. Here are some effective strategies:

- Socratic Questioning: This method involves asking thought-provoking questions that encourage students to think deeply about a topic. For example, instead of asking, “What is the capital of France?” you might ask, “Why do you think Paris became the capital of France?”

- Debates and Discussions: Debates and open-ended discussions allow students to explore different viewpoints and challenge their own beliefs. For example, a debate on a current event can engage students in critical analysis of the situation.

- Teaching Metacognition: Teaching students to think about their own thinking can enhance their critical thinking skills. This can be achieved through activities such as reflective writing or journaling.

- Problem-Solving Activities: As with developing problem-solving skills , activities that require students to find solutions to complex problems can also foster critical thinking.

As a school leader, I’ve seen the transformative power of critical thinking. During a school competition, I observed a team of students tasked with proposing a solution to reduce our school’s environmental impact. Instead of jumping to obvious solutions, they critically evaluated multiple options, considering the feasibility, cost, and potential impact of each. They ultimately proposed a comprehensive plan that involved water conservation, waste reduction, and energy efficiency measures. This demonstrated their ability to critically analyze a problem and develop an effective solution.

Critical thinking is an essential skill for students in the 21st century. It equips them to understand and navigate the world in a thoughtful and informed manner. As a teacher, incorporating strategies to foster critical thinking in your classroom can make a lasting impact on your students’ educational journey and life beyond school.

1. What is critical thinking? Critical thinking is the ability to analyze information objectively and make a reasoned judgment.

2. Why is critical thinking important for students? Critical thinking helps students make informed decisions, develop analytical skills, and promotes independence.

3. What are some strategies to cultivate critical thinking in students? Strategies can include Socratic questioning, debates and discussions, teaching metacognition, and problem-solving activities.

4. How can I assess my students’ critical thinking skills? You can assess critical thinking skills through essays, presentations, discussions, and problem-solving tasks that require thoughtful analysis.

5. Can critical thinking be taught? Yes, critical thinking can be taught and nurtured through specific teaching strategies and a supportive learning environment.

Related Posts

7 simple strategies for strong student-teacher relationships.

Getting to know your students on a personal level is the first step towards building strong relationships. Show genuine interest in their lives outside the classroom.

Connecting Learning to Real-World Contexts: Strategies for Teachers

When students see the relevance of their classroom lessons to their everyday lives, they are more likely to be motivated, engaged, and retain information.

Encouraging Active Involvement in Learning: Strategies for Teachers

Active learning benefits students by improving retention of information, enhancing critical thinking skills, and encouraging a deeper understanding of the subject matter.

Collaborative and Cooperative Learning: A Guide for Teachers

These methods encourage students to work together, share ideas, and actively participate in their education.

Experiential Teaching: Role-Play and Simulations in Teaching

These interactive techniques allow students to immerse themselves in practical, real-world scenarios, thereby deepening their understanding and retention of key concepts.

Project-Based Learning Activities: A Guide for Teachers

Project-Based Learning is a student-centered pedagogy that involves a dynamic approach to teaching, where students explore real-world problems or challenges.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Critical thinking is a 21st-century essential — here’s how to help kids learn it

Share this idea.

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

If we want children to thrive in our complicated world, we need to teach them how to think, says educator Brian Oshiro. And we can do it with 4 simple questions.

This post is part of TED’s “How to Be a Better Human” series, each of which contains a piece of helpful advice from someone in the TED community; browse through all the posts here.

We all want the young people in our lives to thrive, but there’s no clear consensus about what will best put them on the path to future success. Should every child be taught to code? Attain fluency in Mandarin, Spanish, Hindi and English?

Those are great, but they’re not enough, says educator and teacher trainer Brian Oshiro . If we want our children to have flexible minds that can readily absorb new information and respond to complex problems, he says, we need to develop their critical thinking skills.

In adult life, “we all have to deal with questions that are a lot more complicated than those found on a multiple-choice test,” he says in a TEDxXiguan talk. “We need to give students an opportunity to grapple with questions that don’t necessarily have one correct answer. This is more realistic of the types of situations that they’re likely to face when they get outside the classroom.”

How can we encourage kids to think critically from an early age? Through an activity that every child is already an expert at — asking questions.

1. Go beyond “what?” — and ask “how?” and “why?”

Let’s say your child is learning about climate change in school. Their teacher may ask them a question like “What are the main causes of climate change?” Oshiro says there are two problems with this question — it can be answered with a quick web search, and being able to answer it gives people a false sense of security; it makes them feel like they know a topic, but their knowledge is superficial.

At home, prompt your kid to answer questions such as “ How exactly does X cause climate change?” and “ Why should we worry about it?” To answer, they’ll need to go beyond the bare facts and really think about a subject.

Other great questions: “ How will climate change affect where we live?” or “ Why should our town in particular worry about climate change?” Localizing questions gives kids, says Oshiro, “an opportunity to connect whatever knowledge they have to something personal in their lives.”

2. Follow it up with “How do you know this?”

Oshiro says, “They have to provide some sort of evidence and be able to defend their answer against some logical attack.” Answering this question requires kids to reflect on their previous statements and assess where they’re getting their information from.

3. Prompt them to think about how their perspective may differ from other people’s.

Ask a question like “How will climate change affect people living in X country or X city?” or “Why should people living in X country or X city worry about it?” Kids will be pushed to think about the priorities and concerns of others, says Oshiro, and to try to understand their perspectives — essential elements of creative problem-solving.

4. Finally, ask them how to solve this problem.

But be sure to focus the question. For example, rather than ask “How can we solve climate change?” — which is too big for anyone to wrap their mind around — ask “How could we address and solve cause X of climate change?” Answering this question will require kids to synthesize their knowledge. Nudge them to come up with a variety of approaches: What scientific solution could address cause X? What’s a financial solution? Political solution?

You can start this project any time on any topic; you don’t have to be an expert on what your kids are studying. This is about teaching them to think for themselves. Your role is to direct their questions, listen and respond. Meanwhile, your kids “have to think about how they’re going to put this into digestible pieces for you to understand it,” says Oshiro. “It’s a great way to consolidate learning.”

Critical thinking isn’t just for the young, of course. He says, “If you’re a lifelong learner, ask yourself these types of questions in order to test your assumptions about what you think you already know.” As he adds, “We can all improve and support critical thinking by asking a few extra questions each day.”

Watch his TEDxXiguan talk now:

About the author

Mary Halton is a science journalist based in the Pacific Northwest. You can find her on Twitter at @maryhalton

- brian oshiro

- how to be a better human

TED Talk of the Day

How to make radical climate action the new normal

6 ways to give that aren't about money

A smart way to handle anxiety -- courtesy of soccer great Lionel Messi

How do top athletes get into the zone? By getting uncomfortable

6 things people do around the world to slow down

Creating a contract -- yes, a contract! -- could help you get what you want from your relationship

Could your life story use an update? Here’s how to do it

6 tips to help you be a better human now

How to have better conversations on social media (really!)

3 strategies for effective leadership, from a former astronaut

A pair of practices to help you raise financially responsible kids

The secret to giving a compliment that makes people glow

How to raise kids who will grow into secure, trustworthy adults

How to help a teacher out

How Parents Can Teach Kids Critical Thinking

A research-based guide to help highlight the importance of critical thinking..

Posted February 21, 2020

Recent controversy over the role of social media “ swarms ” in the 2020 election have served as a new reminder — as if we needed one — that public discourse is in bad disrepair. In the last few years have seen countless incidents of people — including many who should know better — weighing in on issues prematurely with little nuance and unhelpful vitriol, being duped by badly biased information or outright fake news , and automatically attributing the worst intentions to their opponents.

Liberal democracies have always relied on flawed sources to inform the public, but not until now have we been confronted with an online medium seemingly designed to play on our biases and emotions; encourage knee-jerk reactions, groupthink , and superficiality; and distract us from deeper thinking.

Better critical thinking skills are needed to help us confront these challenges. Nevertheless, we still don’t have a good handle on what it is and, especially, how best to foster it among children of all ages.

The stakes are now higher than ever.

To address this deficit, Reboot Foundation recently put out a Parents’ Guide to critical thinking. I work for Reboot and helped on the guide that attempts to give parents and other adults the tools and understanding they need to help their kids cope with technological upheaval, acquire the skills they need to navigate an ever more complicated and information-rich world, and overcome the pitfalls of biased and emotional reasoning.

1. Starting Young

As researchers have noted for some time now, critical thinking can’t be cleanly separated from cognitive development more generally. So, although many people still think of critical thinking as something that is appropriate to teach only in college or late high school, parents and educators should actually devote attention to developing critical thinking skills at a young age.

Of course, it’s not necessary or even possible to start teaching 4-year-olds high-level logic . But there’s a lot parents can do to open up their children’s minds to the world around them. The most important thing to foster at this young age is what researchers call metacognition : awareness of one’s own thinking and thought processes.

It’s only with metacognition that children will learn to think more strategically, identify errors in their thinking patterns, and recognize their own limitations and the value of others’ perspectives. Here are some good ways to foster these habits of mind.

- Encourage kids’ curiosity by asking them lots of questions about why they think what they think. Parents should also not dismiss children’s speculative questions, but encourage them to think those questions through.

- Encourage active reading by discussing and reflecting on books and asking children to analyze different characters’ thoughts and attitudes. Emphasize and embrace ambiguity.

- Expose them as much as possible to children from different backgrounds — whether cultural, geographical, or socio-economic. These experiences are invaluable.

- Bring children into adult conversations , within appropriate limits of course, and don’t just dismiss their contributions. Even if their contributions are unsophisticated or mistaken, engage with children and help them improve.

2. Putting Emotions in Perspective

Just as children need to learn how to step back from their thought processes, they must also learn how to step back from their emotions. As we’ve seen time and again in our public discourse, emotion is often the enemy of thinking. It can lead us to dismiss legitimate evidence; to shortchange perspectives that would otherwise be valuable; and to say and do things we later regret.

When children are young (ages 5 to 9), fostering emotional management should center around learning to take on new challenges and cope with setbacks. It’s important children be encouraged to try new things and not be protected from failure. These can include both intellectual challenges like learning a new language or musical instrument and physical ones like trying out rock-climbing or running a race.

When children fail — as they will — the adults around them should help them see that failing does not make them failures. Quite the opposite: it’s the only way to become successful.

As they get older, during puberty and adolescence , emotional management skills can help them deal better with confusing physical and social changes and maintain focus on their studies and long-term goals . Critical thinking, in this sense, need not — and should not — be dry or academic. It can have a significant impact on children’s and young adults’ emotional lives and their success beyond the classroom .

3. Learning How to Be Online

Finally, critical thinking development in these challenging times must involve an online component. Good citizenship requires being able to take advantage of the wealth of information the internet offers and knowing how to avoid its many pitfalls.

Parental controls can be useful, especially for younger children, and help them steer clear of inappropriate content. But instilling kids with healthy online habits is ultimately more useful — and durable. Parents should spend time practicing web searches with their kids, teaching them how to evaluate sources and, especially, how to avoid distractions and keep focused on the task at hand.

We’ve all experienced the way the internet can pull us off task and down a rabbit hole of unproductive browsing. These forces can be especially hard for children to resist, and they can have long-term negative effects on their cognitive development.

As they get older, children should learn more robust online research skills , especially in how to identify different types of deceptive information and misinformation . Familiarizing themselves with various fact-checking sites and methods can be especially useful. A recent Reboot study found that schools are still not doing nearly enough to teach media literacy to students.

As kids routinely conduct more and more of their social lives online it’s also vital that they learn to differentiate between the overheated discourse on social media and genuine debate.

The barriers to critical thinking are not insurmountable. But if our public discourse is to come through the current upheaval intact, children, beginning at a young age, must learn the skills to navigate their world thoughtfully and critically.

Ulrich Boser is the founder of The Learning Agency and a senior fellow at the Center for American Progress. He is the author of Learn Better, which Amazon called “the best science book of the year.”

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

It’s increasingly common for someone to be diagnosed with a condition such as ADHD or autism as an adult. A diagnosis often brings relief, but it can also come with as many questions as answers.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

For Employers

Bright horizons family solutions, edassist by bright horizons, bright horizons workforce consulting, featured industry: healthcare, find a center.

Navigate to your portal

Select a path to log in to your desired Bright Horizons website.

Child Care Center

Access your day-to-day childcare activities and communications through the Family Information Center.

Employee Benefits

Access your employer-sponsored benefits such as Back-Up Care, EdAssist, and more.

Child Care Center.

Locate our child care centers, preschools, and schools near you

Need to make a reservation to use your Bright Horizons Back-Up Care?

I'm interested in

Developing critical thinking skills in kids.

Developing Critical Thinking Skills

Learning to think critically may be one of the most important skills that today's children will need for the future. In today’s rapidly changing world, children need to be able to do much more than repeat a list of facts; they need to be critical thinkers who can make sense of information, analyze, compare, contrast, make inferences, and generate higher order thinking skills.

Building Your Child's Critical Thinking Skills

Building critical thinking skills happens through day-to-day interactions as you talk with your child, ask open-ended questions, and allow your child to experiment and solve problems. Here are some tips and ideas to help children build a foundation for critical thinking:

- Provide opportunities for play . Building with blocks, acting out roles with friends, or playing board games all build children’s critical thinking.

- Pause and wait. Offering your child ample time to think, attempt a task, or generate a response is critical. This gives your child a chance to reflect on her response and perhaps refine, rather than responding with their very first gut reaction.

- Don't intervene immediately. Kids need challenges to grow. Wait and watch before you jump in to solve a problem.

- Ask open-ended questions. Rather than automatically giving answers to the questions your child raises, help them think critically by asking questions in return: "What ideas do you have? What do you think is happening here?" Respect their responses whether you view them as correct or not. You could say, "That is interesting. Tell me why you think that."

- Help children develop hypotheses. Taking a moment to form hypotheses during play is a critical thinking exercise that helps develop skills. Try asking your child, "If we do this, what do you think will happen?" or "Let's predict what we think will happen next."

- Encourage thinking in new and different ways. By allowing children to think differently, you're helping them hone their creative problem solving skills. Ask questions like, "What other ideas could we try?" or encourage your child to generate options by saying, "Let’s think of all the possible solutions."

Of course, there are situations where you as a parent need to step in. At these times, it is helpful to model your own critical thinking. As you work through a decision making process, verbalize what is happening inside your mind. Children learn from observing how you think. Taking time to allow your child to navigate problems is integral to developing your child's critical thinking skills in the long run.

Recommended for you

- preparing for kindergarten

- language development

- Working Parents

- digital age parenting

- Student Loans

We have a library of resources for you about all kinds of topics like this!

- Grades 6-12

- School Leaders

Have you entered to win this adorable math giveaway? ✨

What Is Critical Thinking and Why Do We Need To Teach It?

Question the world and sort out fact from opinion.

The world is full of information (and misinformation) from books, TV, magazines, newspapers, online articles, social media, and more. Everyone has their own opinions, and these opinions are frequently presented as facts. Making informed choices is more important than ever, and that takes strong critical thinking skills. But what exactly is critical thinking? Why should we teach it to our students? Read on to find out.

What is critical thinking?

Source: Indeed

Critical thinking is the ability to examine a subject and develop an informed opinion about it. It’s about asking questions, then looking closely at the answers to form conclusions that are backed by provable facts, not just “gut feelings” and opinion. These skills allow us to confidently navigate a world full of persuasive advertisements, opinions presented as facts, and confusing and contradictory information.

The Foundation for Critical Thinking says, “Critical thinking can be seen as having two components: 1) a set of information and belief-generating and processing skills, and 2) the habit, based on intellectual commitment, of using those skills to guide behavior.”

In other words, good critical thinkers know how to analyze and evaluate information, breaking it down to separate fact from opinion. After a thorough analysis, they feel confident forming their own opinions on a subject. And what’s more, critical thinkers use these skills regularly in their daily lives. Rather than jumping to conclusions or being guided by initial reactions, they’ve formed the habit of applying their critical thinking skills to all new information and topics.

Why is critical thinking so important?

Imagine you’re shopping for a new car. It’s a big purchase, so you want to do your research thoroughly. There’s a lot of information out there, and it’s up to you to sort through it all.

- You’ve seen TV commercials for a couple of car models that look really cool and have features you like, such as good gas mileage. Plus, your favorite celebrity drives that car!

- The manufacturer’s website has a lot of information, like cost, MPG, and other details. It also mentions that this car has been ranked “best in its class.”

- Your neighbor down the street used to have this kind of car, but he tells you that he eventually got rid of it because he didn’t think it was comfortable to drive. Plus, he heard that brand of car isn’t as good as it used to be.

- Three independent organizations have done test-drives and published their findings online. They all agree that the car has good gas mileage and a sleek design. But they each have their own concerns or complaints about the car, including one that found it might not be safe in high winds.

So much information! It’s tempting to just go with your gut and buy the car that looks the coolest (or is the cheapest, or says it has the best gas mileage). Ultimately, though, you know you need to slow down and take your time, or you could wind up making a mistake that costs you thousands of dollars. You need to think critically to make an informed choice.

What does critical thinking look like?

Source: TeachThought

Let’s continue with the car analogy, and apply some critical thinking to the situation.

- Critical thinkers know they can’t trust TV commercials to help them make smart choices, since every single one wants you to think their car is the best option.

- The manufacturer’s website will have some details that are proven facts, but other statements that are hard to prove or clearly just opinions. Which information is factual, and even more important, relevant to your choice?

- A neighbor’s stories are anecdotal, so they may or may not be useful. They’re the opinions and experiences of just one person and might not be representative of a whole. Can you find other people with similar experiences that point to a pattern?

- The independent studies could be trustworthy, although it depends on who conducted them and why. Closer analysis might show that the most positive study was conducted by a company hired by the car manufacturer itself. Who conducted each study, and why?

Did you notice all the questions that started to pop up? That’s what critical thinking is about: asking the right questions, and knowing how to find and evaluate the answers to those questions.

Good critical thinkers do this sort of analysis every day, on all sorts of subjects. They seek out proven facts and trusted sources, weigh the options, and then make a choice and form their own opinions. It’s a process that becomes automatic over time; experienced critical thinkers question everything thoughtfully, with purpose. This helps them feel confident that their informed opinions and choices are the right ones for them.

Key Critical Thinking Skills

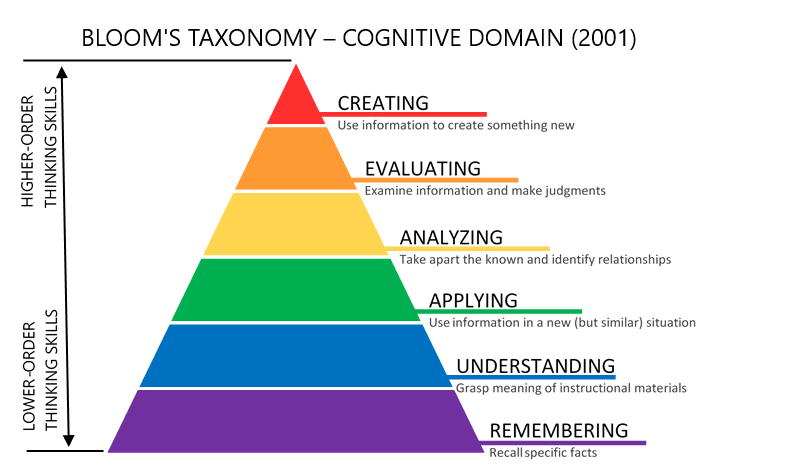

There’s no official list, but many people use Bloom’s Taxonomy to help lay out the skills kids should develop as they grow up.

Source: Vanderbilt University

Bloom’s Taxonomy is laid out as a pyramid, with foundational skills at the bottom providing a base for more advanced skills higher up. The lowest phase, “Remember,” doesn’t require much critical thinking. These are skills like memorizing math facts, defining vocabulary words, or knowing the main characters and basic plot points of a story.

Higher skills on Bloom’s list incorporate more critical thinking.

True understanding is more than memorization or reciting facts. It’s the difference between a child reciting by rote “one times four is four, two times four is eight, three times four is twelve,” versus recognizing that multiplication is the same as adding a number to itself a certain number of times. When you understand a concept, you can explain how it works to someone else.

When you apply your knowledge, you take a concept you’ve already mastered and apply it to new situations. For instance, a student learning to read doesn’t need to memorize every word. Instead, they use their skills in sounding out letters to tackle each new word as they come across it.

When we analyze something, we don’t take it at face value. Analysis requires us to find facts that stand up to inquiry. We put aside personal feelings or beliefs, and instead identify and scrutinize primary sources for information. This is a complex skill, one we hone throughout our entire lives.

Evaluating means reflecting on analyzed information, selecting the most relevant and reliable facts to help us make choices or form opinions. True evaluation requires us to put aside our own biases and accept that there may be other valid points of view, even if we don’t necessarily agree with them.

Finally, critical thinkers are ready to create their own result. They can make a choice, form an opinion, cast a vote, write a thesis, debate a topic, and more. And they can do it with the confidence that comes from approaching the topic critically.

How do you teach critical thinking skills?

The best way to create a future generation of critical thinkers is to encourage them to ask lots of questions. Then, show them how to find the answers by choosing reliable primary sources. Require them to justify their opinions with provable facts, and help them identify bias in themselves and others. Try some of these resources to get started.

5 Critical Thinking Skills Every Kid Needs To Learn (And How To Teach Them)

- 100+ Critical Thinking Questions for Students To Ask About Anything

- 10 Tips for Teaching Kids To Be Awesome Critical Thinkers

- Free Critical Thinking Poster, Rubric, and Assessment Ideas

More Critical Thinking Resources

The answer to “What is critical thinking?” is a complex one. These resources can help you dig more deeply into the concept and hone your own skills.

- The Foundation for Critical Thinking

- Cultivating a Critical Thinking Mindset (PDF)

- Asking the Right Questions: A Guide to Critical Thinking (Browne/Keeley, 2014)

Have more questions about what critical thinking is or how to teach it in your classroom? Join the WeAreTeachers HELPLINE group on Facebook to ask for advice and share ideas!

Plus, 12 skills students can work on now to help them in careers later ..

You Might Also Like

Teach them to thoughtfully question the world around them. Continue Reading

Copyright © 2024. All rights reserved. 5335 Gate Parkway, Jacksonville, FL 32256

Thinking about thinking helps kids learn. How can we teach critical thinking?

Lecturer in Critical Thinking; Curriculum Director, UQ Critical Thinking Project, The University of Queensland

Disclosure statement

Peter Ellerton consults to the Centre for Critical and Creative Thinking. He is a Fellow of the Rationalist Society of Australia.

University of Queensland provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

Few people doubt the value of developing students’ thinking skills. A 2013 survey in the United States found 93% of employers believe a candidate’s

demonstrated capacity to think critically, communicate clearly, and solve complex problems is more important [the emphasis is in the original] than [their] undergraduate major.

A focus on critical thinking is also common in education. In the Australian Curriculum, critical and creative thinking are known as “ general capabilities ”; the US has a similar focus through their “ common core ”.

Critical thinking is being taught successfully in a number of programs in Australian schools and universities and around the world. And various studies show these programs improve students’ thinking ability and even their standardised test scores.

But what is critical thinking and how can we teach it?

What we mean by critical thinking

There are many definitions of critical thinking that are vague or ill-formed. To help address this, let’s start by saying what critical thinking is not.

First, critical thinking is not just being smart. Being able to recognise a problem and find the solution are characteristics we associate with intelligence. But they are by themselves not critical thinking.

Intelligence, at least as measured by IQ tests, is not set in stone. But it does not seem to be strongly affected by education (all other things being equal), requiring years of study to make any significant difference, if at all. The ability to think critically, however, can improve significantly with much shorter interventions, as I will show.

Read more: Knowledge is a process of discovery: how constructivism changed education

Second, critical thinking is not just difficult thinking. Some thinking we see as hard, such as performing a complex chemical analysis, could be done by computers. Critical thinking is more about the quality of thinking than the difficulty of a problem.

So, how do we understand what good quality thinking is?

Critical thinkers have the ability to evaluate their own thinking using standards of good reasoning. These include what we collectively call the values of inquiry such as precision, clarity, depth and breadth of treatment, coherence, significance and relevance.

I might claim the temperature of the planet is increasing, or that the rate of deforestation in the Amazon is greater than it was last year. While these statements are accurate, they lack precision: we would also like to know by how much they are increasing to make the statement more meaningful.

Or I might wonder if the biodiversity of Tasmania’s old growth forests would be affected by logging. Someone might reply if we did not log these forests, jobs and livelihoods would be at risk. A good critical thinker will point out while this is a significant issue, it is not relevant to the question .

Critical thinkers also examine the structure of arguments to evaluate the strength of claims. This is not just about deciding whether a claim is true or not, but also whether a conclusion can be logically supported by the available data through an understanding of how arguments work.

Critical thinkers make the quality of their thinking an object of study. They are sensitive to the values of inquiry and the quality of inferences drawn from given information.

They are also meta-cognitive - meaning they’re aware of their thought processes (or some of them) such as understanding how and why they arrive at particular conclusions - and have the tools and ability to evaluate and improve their own thinking.

How we can teach it

Many approaches to developing critical thinking are based on Philosophy for Children , a program that involves teaching the methodology of argument and focuses on thinking skills. Other approaches provide this focus outside of a philosophical context.

Read more: How to make good arguments at school (and everywhere else)

Teachers at one Brisbane school, who have extensive training in critical thinking pedagogies, developed a task that asked students to determine Australia’s greatest sports person.

Students needed to construct their own criteria for greatness. To do so, they had to analyse the Australian sporting context, create possible evaluative standards, explain and justify why some standards would be more acceptable than others and apply these to their candidates.

They then needed to argue their case with their peers to develop criteria that were robust, defensible, widely applicable and produced a choice that captured significant and relevant aspects of Australian sport.

Learning experiences and assessment items that facilitate critical thinking skills include those in which students can:

- challenge assumptions

- frame problems collectively

- question creatively

- construct, analyse and evaluate arguments

- discerningly apply values of inquiry

- engage in a wide variety of cognitive skills, including analysing, explaining, justifying and evaluating (which creates possibilities for argument construction and evaluation and for applying the values of inquiry)

One strategy that also has a large impact on students’ ability to analyse and evaluate arguments is argument mapping , in which a student’s reasoning can be visually displayed by capturing the inferential pathway from premises to conclusion. Argument maps are an important tool in making our reasoning available for analysis and evaluation.

How we know it works

Studies involving a Philosophy for Children approach show children experience cognitive gains , as measured by improved academic outcomes, for several years after having weekly classes for a year compared to their peers.

Read more: Who am I? Why am I here? Why children should be taught philosophy (beyond better test scores)

This type of argument-based intellectual engagement , however, can show high outcomes in terms of the quality of thinking in any classroom.

Research also shows deliberate attention to the practice of reasoning in the context of our everyday lives can be significantly improved through targeted teaching.

Researchers looking at the gains made in a single semester of teaching critical thinking with argument maps said

the critical thinking gains measured […] are close to that which could be expected to result from three years of undergraduate education.

Students who are explicitly taught to think well also do better on subject-based exams and standardised tests than those who do not.

Our yet-to-be-published study, using verified data, showed students in years three to nine who engaged in a series of 12 one-hour teacher-facilitated online lessons in critical thinking, showed a significant increase in relative gains in NAPLAN test results – as measured against a control group and after controlling for other variables.

In terms of developing 21st century skills, which includes setting up students for lifelong learning, teaching critical thinking should be core business.

The University of Queensland Critical Thinking Project has a number of tools to help teach critical thinking skills. One is a web-based mapping system , now in use in a number of schools and universities, to help increase the critical thinking abilities of students.

- Critical thinking

- Critical thinking skills

Service Centre Senior Consultant

Director of STEM

Community member - Training Delivery and Development Committee (Volunteer part-time)

Chief Executive Officer

Head of Evidence to Action

ChatGPT for Teachers

Trauma-informed practices in schools, teacher well-being, cultivating diversity, equity, & inclusion, integrating technology in the classroom, social-emotional development, covid-19 resources, invest in resilience: summer toolkit, civics & resilience, all toolkits, degree programs, trauma-informed professional development, teacher licensure & certification, how to become - career information, classroom management, instructional design, lifestyle & self-care, online higher ed teaching, current events, teaching critical thinking skills.

The pervasiveness of social media has significantly changed how people receive and understand information. By steering people to content that’s similar to what they have already read, algorithms create echo chambers that can hinder critical thinking. Consequently, the person may not develop critical thinking skills or be able to refine the abilities they already possess.

Teachers can act as the antidote to the algorithms by strengthening their focus on teaching students to think critically. The following discusses how to teach critical thinking skills and provides resources for teachers to help their students.

What is critical thinking?

Oxford: Learner’s Dictionaries defines critical thinking as “the process of analyzing information in order to make a logical decision about the extent to which you believe something to be true or false.” A critical thinker only forms an opinion on a subject after first understanding the available information and then refining their understanding through:

- Comparisons with other sources of information

A person who is capable of critical thought relies entirely on scientific evidence, rather than guesswork or preconceived notions.

Key critical thinking skills

There isn’t a definitive list of key critical thinking skills, but Bloom’s Taxonomy is often used as a guide and illustration. It starts with base skills, such as remembering and understanding, and rises to optimal skills that include evaluating and creating.

- Remembering: Recalling specific facts

- Understanding: Grasping the information’s meaning

- Applying: Using the information in a new but similar situation

- Analyzing: Identifying connections between different source materials

- Evaluating: Examining the information and making judgments

- Creating: Using the information to create something new

Promoting critical thinking in the classroom

A Stanford Medicine study from 2022 finds that one quarter of children aged 10.7 years have mobile phones. This figure rises to 75% by age 12.6 and almost 100% by age 15. Consequently, children are routinely exposed to powerful algorithms that can dull their critical thinking abilities from a very young age.

Teaching critical thinking skills to elementary students can help them develop a way of thinking that can temper the social media biases they inevitably encounter.

At the core of teaching critical thinking skills is encouraging students to ask questions. This can challenge some educators, who may be tempted to respond to the umpteenth question on a single subject with “it just is.” Although that’s a human response when exasperated, it undermines the teacher’s previous good work.

After all, there’s likely little that promotes critical thinking more than feeling safe to ask a question and being encouraged to explore and investigate a subject. Dismissing a question without explanation risks alienating the student and those witnessing the exchange.

How to teach critical thinking skills

Teaching critical thinking skills takes patience and time alongside a combination of instruction and practice. It’s important to routinely create opportunities for children to engage in critical thinking and to guide them through challenges while providing helpful, age-appropriate feedback.

The following covers several of the most common ways of teaching critical thinking skills to elementary students. Teachers should use an array of resources suitable for middle school and high school students.

Encourage curiosity

It’s normal for teachers to ask a question and then pick one of the first hands that rise. But waiting a few moments often sees more hands raised, which helps foster an environment where children are comfortable asking questions. It also encourages them to be more curious when engaging with a subject simply because there’s a greater probability of being asked to answer a question.

It’s important to reward students who demonstrate curiosity and a desire to learn. This not only encourages the student but also shows others the benefits of becoming more involved. Some may be happy to learn whatever is put before them, while others may need a subject in which they already have an interest. Using real-world examples develops curiosity as well because children can connect these with existing experiences.

Model critical thinking

We know children model much of their behavior on what they see and hear in adults. So, one of the best tools in an educator’s toolbox is modeling critical thinking. Sharing their own thoughts as they work through a problem is a good way for teachers to help children see a workable thought process they can mimic. In time, as their confidence and experience grow, they will develop their own strategies.

Encourage debate and discussion

Debating and discussing in a safe space is one of the most effective ways to develop critical thinking skills. Assigning age-appropriate topics, and getting each student to develop arguments for and against a position on that topic, exposes them to different perspectives.