- En español – ExME

- Em português – EME

An introduction to different types of study design

Posted on 6th April 2021 by Hadi Abbas

Study designs are the set of methods and procedures used to collect and analyze data in a study.

Broadly speaking, there are 2 types of study designs: descriptive studies and analytical studies.

Descriptive studies

- Describes specific characteristics in a population of interest

- The most common forms are case reports and case series

- In a case report, we discuss our experience with the patient’s symptoms, signs, diagnosis, and treatment

- In a case series, several patients with similar experiences are grouped.

Analytical Studies

Analytical studies are of 2 types: observational and experimental.

Observational studies are studies that we conduct without any intervention or experiment. In those studies, we purely observe the outcomes. On the other hand, in experimental studies, we conduct experiments and interventions.

Observational studies

Observational studies include many subtypes. Below, I will discuss the most common designs.

Cross-sectional study:

- This design is transverse where we take a specific sample at a specific time without any follow-up

- It allows us to calculate the frequency of disease ( p revalence ) or the frequency of a risk factor

- This design is easy to conduct

- For example – if we want to know the prevalence of migraine in a population, we can conduct a cross-sectional study whereby we take a sample from the population and calculate the number of patients with migraine headaches.

Cohort study:

- We conduct this study by comparing two samples from the population: one sample with a risk factor while the other lacks this risk factor

- It shows us the risk of developing the disease in individuals with the risk factor compared to those without the risk factor ( RR = relative risk )

- Prospective : we follow the individuals in the future to know who will develop the disease

- Retrospective : we look to the past to know who developed the disease (e.g. using medical records)

- This design is the strongest among the observational studies

- For example – to find out the relative risk of developing chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) among smokers, we take a sample including smokers and non-smokers. Then, we calculate the number of individuals with COPD among both.

Case-Control Study:

- We conduct this study by comparing 2 groups: one group with the disease (cases) and another group without the disease (controls)

- This design is always retrospective

- We aim to find out the odds of having a risk factor or an exposure if an individual has a specific disease (Odds ratio)

- Relatively easy to conduct

- For example – we want to study the odds of being a smoker among hypertensive patients compared to normotensive ones. To do so, we choose a group of patients diagnosed with hypertension and another group that serves as the control (normal blood pressure). Then we study their smoking history to find out if there is a correlation.

Experimental Studies

- Also known as interventional studies

- Can involve animals and humans

- Pre-clinical trials involve animals

- Clinical trials are experimental studies involving humans

- In clinical trials, we study the effect of an intervention compared to another intervention or placebo. As an example, I have listed the four phases of a drug trial:

I: We aim to assess the safety of the drug ( is it safe ? )

II: We aim to assess the efficacy of the drug ( does it work ? )

III: We want to know if this drug is better than the old treatment ( is it better ? )

IV: We follow-up to detect long-term side effects ( can it stay in the market ? )

- In randomized controlled trials, one group of participants receives the control, while the other receives the tested drug/intervention. Those studies are the best way to evaluate the efficacy of a treatment.

Finally, the figure below will help you with your understanding of different types of study designs.

References (pdf)

You may also be interested in the following blogs for further reading:

An introduction to randomized controlled trials

Case-control and cohort studies: a brief overview

Cohort studies: prospective and retrospective designs

Prevalence vs Incidence: what is the difference?

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

No Comments on An introduction to different types of study design

you are amazing one!! if I get you I’m working with you! I’m student from Ethiopian higher education. health sciences student

Very informative and easy understandable

You are my kind of doctor. Do not lose sight of your objective.

Wow very erll explained and easy to understand

I’m Khamisu Habibu community health officer student from Abubakar Tafawa Balewa university teaching hospital Bauchi, Nigeria, I really appreciate your write up and you have make it clear for the learner. thank you

well understood,thank you so much

Well understood…thanks

Simply explained. Thank You.

Thanks a lot for this nice informative article which help me to understand different study designs that I felt difficult before

That’s lovely to hear, Mona, thank you for letting the author know how useful this was. If there are any other particular topics you think would be useful to you, and are not already on the website, please do let us know.

it is very informative and useful.

thank you statistician

Fabulous to hear, thank you John.

Thanks for this information

Thanks so much for this information….I have clearly known the types of study design Thanks

That’s so good to hear, Mirembe, thank you for letting the author know.

Very helpful article!! U have simplified everything for easy understanding

I’m a health science major currently taking statistics for health care workers…this is a challenging class…thanks for the simified feedback.

That’s good to hear this has helped you. Hopefully you will find some of the other blogs useful too. If you see any topics that are missing from the website, please do let us know!

Hello. I liked your presentation, the fact that you ranked them clearly is very helpful to understand for people like me who is a novelist researcher. However, I was expecting to read much more about the Experimental studies. So please direct me if you already have or will one day. Thank you

Dear Ay. My sincere apologies for not responding to your comment sooner. You may find it useful to filter the blogs by the topic of ‘Study design and research methods’ – here is a link to that filter: https://s4be.cochrane.org/blog/topic/study-design/ This will cover more detail about experimental studies. Or have a look on our library page for further resources there – you’ll find that on the ‘Resources’ drop down from the home page.

However, if there are specific things you feel you would like to learn about experimental studies, that are missing from the website, it would be great if you could let me know too. Thank you, and best of luck. Emma

Great job Mr Hadi. I advise you to prepare and study for the Australian Medical Board Exams as soon as you finish your undergrad study in Lebanon. Good luck and hope we can meet sometime in the future. Regards ;)

You have give a good explaination of what am looking for. However, references am not sure of where to get them from.

Subscribe to our newsletter

You will receive our monthly newsletter and free access to Trip Premium.

Related Articles

Cluster Randomized Trials: Concepts

This blog summarizes the concepts of cluster randomization, and the logistical and statistical considerations while designing a cluster randomized controlled trial.

Expertise-based Randomized Controlled Trials

This blog summarizes the concepts of Expertise-based randomized controlled trials with a focus on the advantages and challenges associated with this type of study.

A well-designed cohort study can provide powerful results. This blog introduces prospective and retrospective cohort studies, discussing the advantages, disadvantages and use of these type of study designs.

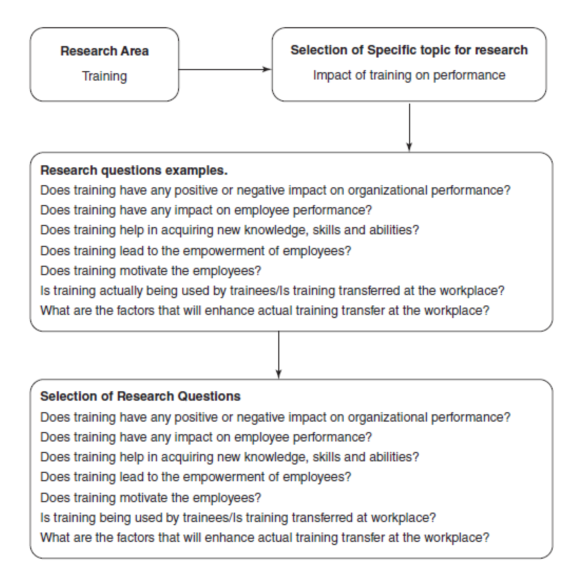

Research Strategies and Methods

- First Online: 22 July 2021

Cite this chapter

- Paul Johannesson 3 &

- Erik Perjons 3

3176 Accesses

Researchers have since centuries used research methods to support the creation of reliable knowledge based on empirical evidence and logical arguments. This chapter offers an overview of established research strategies and methods with a focus on empirical research in the social sciences. We discuss research strategies, such as experiment, survey, case study, ethnography, grounded theory, action research, and phenomenology. Research methods for data collection are also described, including questionnaires, interviews, focus groups, observations, and documents. Qualitative and quantitative methods for data analysis are discussed. Finally, the use of research strategies and methods within design science is investigated.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Bhattacherjee A (2012) Social science research: principles, methods, and practices, 2 edn. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, Tampa, FL

Google Scholar

Blake W (2012) Delphi complete works of William Blake, 2nd edn. Delphi Classics

Bradburn NM, Sudman S, Wansink B (2004) Asking questions: the definitive guide to questionnaire design – for market research, political polls, and social and health questionnaires, revised edition. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco

Bryman A (2016) Social research methods, 5th edn. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Charmaz K (2014) Constructing grounded theory, 2nd edn. SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA

Coghlan D (2019) Doing action research in your own organization, 5th edn. SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA

Creswell JW, Creswell JD (2017) Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches, 5th edn. SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA

MATH Google Scholar

Denscombe M (2017) The good research guide, 6th edn. Open University Press, London

Dey I (2003) Qualitative data analysis: a user friendly guide for social scientists. Routledge, London

Book Google Scholar

Fairclough N (2013) Critical discourse analysis: the critical study of language, 2 edn. Routledge, London

Field A, Hole GJ (2003) How to design and report experiments, 1st edn. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA

Fowler FJ (2013) Survey research methods, 5th edn. SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA

Glaser B, Strauss A (1999) The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. Routledge, London

Kemmis S, McTaggart R, Nixon R (2016) The action research planner: doing critical participatory action research, 1st edn. Springer, Berlin

Krippendorff K (2018) Content analysis: an introduction to its methodology, 4th edn. SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA

LeCompte MD, Schensul JJ (2010) Designing and conducting ethnographic research: an introduction, 2nd edn. AltaMira Press, Lanham, MD

McNiff J (2013) Action research: principles and practice, 3rd edn. Routledge, London

Oates BJ (2006) Researching information systems and computing. SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA

Peterson RA (2000) Constructing effective questionnaires. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks

Prior L (2008) Repositioning documents in social research. Sociology 42(5):821–836

Article Google Scholar

Seidman I (2019) Interviewing as qualitative research: a guide for researchers in education and the social sciences, 5th edn. Teachers College Press, New York

Silverman D (2018) Doing qualitative research, 5th edn. SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA

Stephens L (2004) Advanced statistics demystified, 1st edn. McGraw-Hill Professional, New York

Urdan TC (2016) Statistics in plain English, 4th ed. Routledge, London

Yin RK (2017) Case study research and applications: design and methods, 6th edn. SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Stockholm University, Kista, Sweden

Paul Johannesson & Erik Perjons

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Johannesson, P., Perjons, E. (2021). Research Strategies and Methods. In: An Introduction to Design Science. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-78132-3_3

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-78132-3_3

Published : 22 July 2021

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-78131-6

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-78132-3

eBook Packages : Computer Science Computer Science (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

The PMC website is updating on October 15, 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Indian J Anaesth

- v.60(9); 2016 Sep

Types of studies and research design

Mukul chandra kapoor.

Department of Anesthesiology, Max Smart Super Specialty Hospital, New Delhi, India

Medical research has evolved, from individual expert described opinions and techniques, to scientifically designed methodology-based studies. Evidence-based medicine (EBM) was established to re-evaluate medical facts and remove various myths in clinical practice. Research methodology is now protocol based with predefined steps. Studies were classified based on the method of collection and evaluation of data. Clinical study methodology now needs to comply to strict ethical, moral, truth, and transparency standards, ensuring that no conflict of interest is involved. A medical research pyramid has been designed to grade the quality of evidence and help physicians determine the value of the research. Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have become gold standards for quality research. EBM now scales systemic reviews and meta-analyses at a level higher than RCTs to overcome deficiencies in the randomised trials due to errors in methodology and analyses.

INTRODUCTION

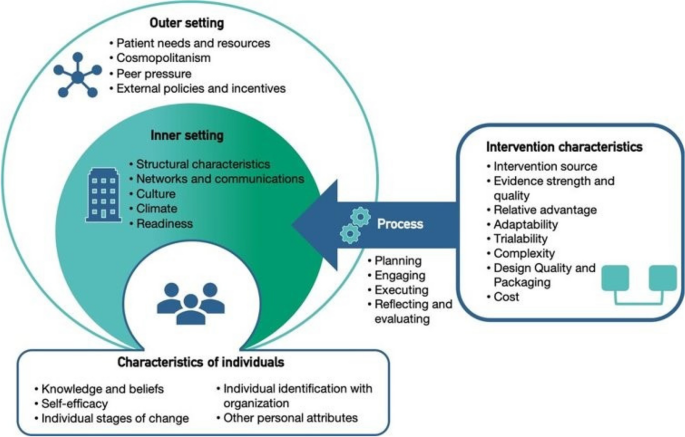

Expert opinion, experience, and authoritarian judgement were the norm in clinical medical practice. At scientific meetings, one often heard senior professionals emphatically expressing ‘In my experience,…… what I have said is correct!’ In 1981, articles published by Sackett et al . introduced ‘critical appraisal’ as they felt a need to teach methods of understanding scientific literature and its application at the bedside.[ 1 ] To improve clinical outcomes, clinical expertise must be complemented by the best external evidence.[ 2 ] Conversely, without clinical expertise, good external evidence may be used inappropriately [ Figure 1 ]. Practice gets outdated, if not updated with current evidence, depriving the clientele of the best available therapy.

Triad of evidence-based medicine

EVIDENCE-BASED MEDICINE

In 1971, in his book ‘Effectiveness and Efficiency’, Archibald Cochrane highlighted the lack of reliable evidence behind many accepted health-care interventions.[ 3 ] This triggered re-evaluation of many established ‘supposed’ scientific facts and awakened physicians to the need for evidence in medicine. Evidence-based medicine (EBM) thus evolved, which was defined as ‘the conscientious, explicit and judicious use of the current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients.’[ 2 ]

The goal of EBM was scientific endowment to achieve consistency, efficiency, effectiveness, quality, safety, reduction in dilemma and limitation of idiosyncrasies in clinical practice.[ 4 ] EBM required the physician to diligently assess the therapy, make clinical adjustments using the best available external evidence, ensure awareness of current research and discover clinical pathways to ensure best patient outcomes.[ 5 ]

With widespread internet use, phenomenally large number of publications, training and media resources are available but determining the quality of this literature is difficult for a busy physician. Abstracts are available freely on the internet, but full-text articles require a subscription. To complicate issues, contradictory studies are published making decision-making difficult.[ 6 ] Publication bias, especially against negative studies, makes matters worse.

In 1993, the Cochrane Collaboration was founded by Ian Chalmers and others to create and disseminate up-to-date review of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) to help health-care professionals make informed decisions.[ 7 ] In 1995, the American College of Physicians and the British Medical Journal Publishing Group collaborated to publish the journal ‘Evidence-based medicine’, leading to the evolution of EBM in all spheres of medicine.

MEDICAL RESEARCH

Medical research needs to be conducted to increase knowledge about the human species, its social/natural environment and to combat disease/infirmity in humans. Research should be conducted in a manner conducive to and consistent with dignity and well-being of the participant; in a professional and transparent manner; and ensuring minimal risk.[ 8 ] Research thus must be subjected to careful evaluation at all stages, i.e., research design/experimentation; results and their implications; the objective of the research sought; anticipated benefits/dangers; potential uses/abuses of the experiment and its results; and on ensuring the safety of human life. Table 1 lists the principles any research should follow.[ 8 ]

General principles of medical research

Types of study design

Medical research is classified into primary and secondary research. Clinical/experimental studies are performed in primary research, whereas secondary research consolidates available studies as reviews, systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Three main areas in primary research are basic medical research, clinical research and epidemiological research [ Figure 2 ]. Basic research includes fundamental research in fields shown in Figure 2 . In almost all studies, at least one independent variable is varied, whereas the effects on the dependent variables are investigated. Clinical studies include observational studies and interventional studies and are subclassified as in Figure 2 .

Classification of types of medical research

Interventional clinical study is performed with the purpose of studying or demonstrating clinical or pharmacological properties of drugs/devices, their side effects and to establish their efficacy or safety. They also include studies in which surgical, physical or psychotherapeutic procedures are examined.[ 9 ] Studies on drugs/devices are subject to legal and ethical requirements including the Drug Controller General India (DCGI) directives. They require the approval of DCGI recognized Ethics Committee and must be performed in accordance with the rules of ‘Good Clinical Practice’.[ 10 ] Further details are available under ‘Methodology for research II’ section in this issue of IJA. In 2004, the World Health Organization advised registration of all clinical trials in a public registry. In India, the Clinical Trials Registry of India was launched in 2007 ( www.ctri.nic.in ). The International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) mandates its member journals to publish only registered trials.[ 11 ]

Observational clinical study is a study in which knowledge from treatment of persons with drugs is analysed using epidemiological methods. In these studies, the diagnosis, treatment and monitoring are performed exclusively according to medical practice and not according to a specified study protocol.[ 9 ] They are subclassified as per Figure 2 .

Epidemiological studies have two basic approaches, the interventional and observational. Clinicians are more familiar with interventional research, whereas epidemiologists usually perform observational research.

Interventional studies are experimental in character and are subdivided into field and group studies, for example, iodine supplementation of cooking salt to prevent hypothyroidism. Many interventions are unsuitable for RCTs, as the exposure may be harmful to the subjects.

Observational studies can be subdivided into cohort, case–control, cross-sectional and ecological studies.

- Cohort studies are suited to detect connections between exposure and development of disease. They are normally prospective studies of two healthy groups of subjects observed over time, in which one group is exposed to a specific substance, whereas the other is not. The occurrence of the disease can be determined in the two groups. Cohort studies can also be retrospective

- Case–control studies are retrospective analyses performed to establish the prevalence of a disease in two groups exposed to a factor or disease. The incidence rate cannot be calculated, and there is also a risk of selection bias and faulty recall.

Secondary research

Narrative review.

An expert senior author writes about a particular field, condition or treatment, including an overview, and this information is fortified by his experience. The article is in a narrative format. Its limitation is that one cannot tell whether recommendations are based on author's clinical experience, available literature and why some studies were given more emphasis. It can be biased, with selective citation of reports that reinforce the authors' views of a topic.[ 12 ]

Systematic review

Systematic reviews methodically and comprehensively identify studies focused on a specified topic, appraise their methodology, summate the results, identify key findings and reasons for differences across studies, and cite limitations of current knowledge.[ 13 ] They adhere to reproducible methods and recommended guidelines.[ 14 ] The methods used to compile data are explicit and transparent, allowing the reader to gauge the quality of the review and the potential for bias.[ 15 ]

A systematic review can be presented in text or graphic form. In graphic form, data of different trials can be plotted with the point estimate and 95% confidence interval for each study, presented on an individual line. A properly conducted systematic review presents the best available research evidence for a focused clinical question. The review team may obtain information, not available in the original reports, from the primary authors. This ensures that findings are consistent and generalisable across populations, environment, therapies and groups.[ 12 ] A systematic review attempts to reduce bias identification and studies selection for review, using a comprehensive search strategy and specifying inclusion criteria. The strength of a systematic review lies in the transparency of each phase and highlighting the merits of each decision made, while compiling information.

Meta-analysis

A review team compiles aggregate-level data in each primary study, and in some cases, data are solicited from each of the primary studies.[ 16 , 17 ] Although difficult to perform, individual patient meta-analyses offer advantages over aggregate-level analyses.[ 18 ] These mathematically pooled results are referred to as meta-analysis. Combining data from well-conducted primary studies provide a precise estimate of the “true effect.”[ 19 ] Pooling the samples of individual studies increases overall sample size, enhances statistical analysis power, reduces confidence interval and thereby improves statistical value.

The structured process of Cochrane Collaboration systematic reviews has contributed to the improvement of their quality. For the meta-analysis to be definitive, the primary RCTs should have been conducted methodically. When the existing studies have important scientific and methodological limitations, such as smaller sized samples, the systematic review may identify where gaps exist in the available literature.[ 20 ] RCTs and systematic review of several randomised trials are less likely to mislead us, and thereby help judge whether an intervention is better.[ 2 ] Practice guidelines supported by large RCTs and meta-analyses are considered as ‘gold standard’ in EBM. This issue of IJA is accompanied by an editorial on Importance of EBM on research and practice (Guyat and Sriganesh 471_16).[ 21 ] The EBM pyramid grading the value of different types of research studies is shown in Figure 3 .

The evidence-based medicine pyramid

In the last decade, a number of studies and guidelines brought about path-breaking changes in anaesthesiology and critical care. Some guidelines such as the ‘Surviving Sepsis Guidelines-2004’[ 22 ] were later found to be flawed and biased. A number of large RCTs were rejected as their findings were erroneous. Another classic example is that of ENIGMA-I (Evaluation of Nitrous oxide In the Gas Mixture for Anaesthesia)[ 23 ] which implicated nitrous oxide for poor outcomes, but ENIGMA-II[ 24 , 25 ] conducted later, by the same investigators, declared it as safe. The rise and fall of the ‘tight glucose control’ regimen was similar.[ 26 ]

Although RCTs are considered ‘gold standard’ in research, their status is at crossroads today. RCTs have conflicting interests and thus must be evaluated with careful scrutiny. EBM can promote evidence reflected in RCTs and meta-analyses. However, it cannot promulgate evidence not reflected in RCTs. Flawed RCTs and meta-analyses may bring forth erroneous recommendations. EBM thus should not be restricted to RCTs and meta-analyses but must involve tracking down the best external evidence to answer our clinical questions.

Financial support and sponsorship

Conflicts of interest.

There are no conflicts of interest.

- Open access

- Published: 07 September 2020

A tutorial on methodological studies: the what, when, how and why

- Lawrence Mbuagbaw ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5855-5461 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Daeria O. Lawson 1 ,

- Livia Puljak 4 ,

- David B. Allison 5 &

- Lehana Thabane 1 , 2 , 6 , 7 , 8

BMC Medical Research Methodology volume 20 , Article number: 226 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

42k Accesses

60 Citations

60 Altmetric

Metrics details

Methodological studies – studies that evaluate the design, analysis or reporting of other research-related reports – play an important role in health research. They help to highlight issues in the conduct of research with the aim of improving health research methodology, and ultimately reducing research waste.

We provide an overview of some of the key aspects of methodological studies such as what they are, and when, how and why they are done. We adopt a “frequently asked questions” format to facilitate reading this paper and provide multiple examples to help guide researchers interested in conducting methodological studies. Some of the topics addressed include: is it necessary to publish a study protocol? How to select relevant research reports and databases for a methodological study? What approaches to data extraction and statistical analysis should be considered when conducting a methodological study? What are potential threats to validity and is there a way to appraise the quality of methodological studies?

Appropriate reflection and application of basic principles of epidemiology and biostatistics are required in the design and analysis of methodological studies. This paper provides an introduction for further discussion about the conduct of methodological studies.

Peer Review reports

The field of meta-research (or research-on-research) has proliferated in recent years in response to issues with research quality and conduct [ 1 , 2 , 3 ]. As the name suggests, this field targets issues with research design, conduct, analysis and reporting. Various types of research reports are often examined as the unit of analysis in these studies (e.g. abstracts, full manuscripts, trial registry entries). Like many other novel fields of research, meta-research has seen a proliferation of use before the development of reporting guidance. For example, this was the case with randomized trials for which risk of bias tools and reporting guidelines were only developed much later – after many trials had been published and noted to have limitations [ 4 , 5 ]; and for systematic reviews as well [ 6 , 7 , 8 ]. However, in the absence of formal guidance, studies that report on research differ substantially in how they are named, conducted and reported [ 9 , 10 ]. This creates challenges in identifying, summarizing and comparing them. In this tutorial paper, we will use the term methodological study to refer to any study that reports on the design, conduct, analysis or reporting of primary or secondary research-related reports (such as trial registry entries and conference abstracts).

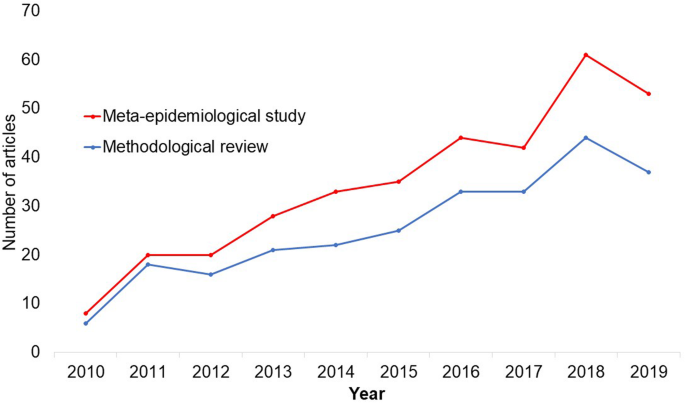

In the past 10 years, there has been an increase in the use of terms related to methodological studies (based on records retrieved with a keyword search [in the title and abstract] for “methodological review” and “meta-epidemiological study” in PubMed up to December 2019), suggesting that these studies may be appearing more frequently in the literature. See Fig. 1 .

Trends in the number studies that mention “methodological review” or “meta-

epidemiological study” in PubMed.

The methods used in many methodological studies have been borrowed from systematic and scoping reviews. This practice has influenced the direction of the field, with many methodological studies including searches of electronic databases, screening of records, duplicate data extraction and assessments of risk of bias in the included studies. However, the research questions posed in methodological studies do not always require the approaches listed above, and guidance is needed on when and how to apply these methods to a methodological study. Even though methodological studies can be conducted on qualitative or mixed methods research, this paper focuses on and draws examples exclusively from quantitative research.

The objectives of this paper are to provide some insights on how to conduct methodological studies so that there is greater consistency between the research questions posed, and the design, analysis and reporting of findings. We provide multiple examples to illustrate concepts and a proposed framework for categorizing methodological studies in quantitative research.

What is a methodological study?

Any study that describes or analyzes methods (design, conduct, analysis or reporting) in published (or unpublished) literature is a methodological study. Consequently, the scope of methodological studies is quite extensive and includes, but is not limited to, topics as diverse as: research question formulation [ 11 ]; adherence to reporting guidelines [ 12 , 13 , 14 ] and consistency in reporting [ 15 ]; approaches to study analysis [ 16 ]; investigating the credibility of analyses [ 17 ]; and studies that synthesize these methodological studies [ 18 ]. While the nomenclature of methodological studies is not uniform, the intents and purposes of these studies remain fairly consistent – to describe or analyze methods in primary or secondary studies. As such, methodological studies may also be classified as a subtype of observational studies.

Parallel to this are experimental studies that compare different methods. Even though they play an important role in informing optimal research methods, experimental methodological studies are beyond the scope of this paper. Examples of such studies include the randomized trials by Buscemi et al., comparing single data extraction to double data extraction [ 19 ], and Carrasco-Labra et al., comparing approaches to presenting findings in Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations (GRADE) summary of findings tables [ 20 ]. In these studies, the unit of analysis is the person or groups of individuals applying the methods. We also direct readers to the Studies Within a Trial (SWAT) and Studies Within a Review (SWAR) programme operated through the Hub for Trials Methodology Research, for further reading as a potential useful resource for these types of experimental studies [ 21 ]. Lastly, this paper is not meant to inform the conduct of research using computational simulation and mathematical modeling for which some guidance already exists [ 22 ], or studies on the development of methods using consensus-based approaches.

When should we conduct a methodological study?

Methodological studies occupy a unique niche in health research that allows them to inform methodological advances. Methodological studies should also be conducted as pre-cursors to reporting guideline development, as they provide an opportunity to understand current practices, and help to identify the need for guidance and gaps in methodological or reporting quality. For example, the development of the popular Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were preceded by methodological studies identifying poor reporting practices [ 23 , 24 ]. In these instances, after the reporting guidelines are published, methodological studies can also be used to monitor uptake of the guidelines.

These studies can also be conducted to inform the state of the art for design, analysis and reporting practices across different types of health research fields, with the aim of improving research practices, and preventing or reducing research waste. For example, Samaan et al. conducted a scoping review of adherence to different reporting guidelines in health care literature [ 18 ]. Methodological studies can also be used to determine the factors associated with reporting practices. For example, Abbade et al. investigated journal characteristics associated with the use of the Participants, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, Timeframe (PICOT) format in framing research questions in trials of venous ulcer disease [ 11 ].

How often are methodological studies conducted?

There is no clear answer to this question. Based on a search of PubMed, the use of related terms (“methodological review” and “meta-epidemiological study”) – and therefore, the number of methodological studies – is on the rise. However, many other terms are used to describe methodological studies. There are also many studies that explore design, conduct, analysis or reporting of research reports, but that do not use any specific terms to describe or label their study design in terms of “methodology”. This diversity in nomenclature makes a census of methodological studies elusive. Appropriate terminology and key words for methodological studies are needed to facilitate improved accessibility for end-users.

Why do we conduct methodological studies?

Methodological studies provide information on the design, conduct, analysis or reporting of primary and secondary research and can be used to appraise quality, quantity, completeness, accuracy and consistency of health research. These issues can be explored in specific fields, journals, databases, geographical regions and time periods. For example, Areia et al. explored the quality of reporting of endoscopic diagnostic studies in gastroenterology [ 25 ]; Knol et al. investigated the reporting of p -values in baseline tables in randomized trial published in high impact journals [ 26 ]; Chen et al. describe adherence to the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement in Chinese Journals [ 27 ]; and Hopewell et al. describe the effect of editors’ implementation of CONSORT guidelines on reporting of abstracts over time [ 28 ]. Methodological studies provide useful information to researchers, clinicians, editors, publishers and users of health literature. As a result, these studies have been at the cornerstone of important methodological developments in the past two decades and have informed the development of many health research guidelines including the highly cited CONSORT statement [ 5 ].

Where can we find methodological studies?

Methodological studies can be found in most common biomedical bibliographic databases (e.g. Embase, MEDLINE, PubMed, Web of Science). However, the biggest caveat is that methodological studies are hard to identify in the literature due to the wide variety of names used and the lack of comprehensive databases dedicated to them. A handful can be found in the Cochrane Library as “Cochrane Methodology Reviews”, but these studies only cover methodological issues related to systematic reviews. Previous attempts to catalogue all empirical studies of methods used in reviews were abandoned 10 years ago [ 29 ]. In other databases, a variety of search terms may be applied with different levels of sensitivity and specificity.

Some frequently asked questions about methodological studies

In this section, we have outlined responses to questions that might help inform the conduct of methodological studies.

Q: How should I select research reports for my methodological study?

A: Selection of research reports for a methodological study depends on the research question and eligibility criteria. Once a clear research question is set and the nature of literature one desires to review is known, one can then begin the selection process. Selection may begin with a broad search, especially if the eligibility criteria are not apparent. For example, a methodological study of Cochrane Reviews of HIV would not require a complex search as all eligible studies can easily be retrieved from the Cochrane Library after checking a few boxes [ 30 ]. On the other hand, a methodological study of subgroup analyses in trials of gastrointestinal oncology would require a search to find such trials, and further screening to identify trials that conducted a subgroup analysis [ 31 ].

The strategies used for identifying participants in observational studies can apply here. One may use a systematic search to identify all eligible studies. If the number of eligible studies is unmanageable, a random sample of articles can be expected to provide comparable results if it is sufficiently large [ 32 ]. For example, Wilson et al. used a random sample of trials from the Cochrane Stroke Group’s Trial Register to investigate completeness of reporting [ 33 ]. It is possible that a simple random sample would lead to underrepresentation of units (i.e. research reports) that are smaller in number. This is relevant if the investigators wish to compare multiple groups but have too few units in one group. In this case a stratified sample would help to create equal groups. For example, in a methodological study comparing Cochrane and non-Cochrane reviews, Kahale et al. drew random samples from both groups [ 34 ]. Alternatively, systematic or purposeful sampling strategies can be used and we encourage researchers to justify their selected approaches based on the study objective.

Q: How many databases should I search?

A: The number of databases one should search would depend on the approach to sampling, which can include targeting the entire “population” of interest or a sample of that population. If you are interested in including the entire target population for your research question, or drawing a random or systematic sample from it, then a comprehensive and exhaustive search for relevant articles is required. In this case, we recommend using systematic approaches for searching electronic databases (i.e. at least 2 databases with a replicable and time stamped search strategy). The results of your search will constitute a sampling frame from which eligible studies can be drawn.

Alternatively, if your approach to sampling is purposeful, then we recommend targeting the database(s) or data sources (e.g. journals, registries) that include the information you need. For example, if you are conducting a methodological study of high impact journals in plastic surgery and they are all indexed in PubMed, you likely do not need to search any other databases. You may also have a comprehensive list of all journals of interest and can approach your search using the journal names in your database search (or by accessing the journal archives directly from the journal’s website). Even though one could also search journals’ web pages directly, using a database such as PubMed has multiple advantages, such as the use of filters, so the search can be narrowed down to a certain period, or study types of interest. Furthermore, individual journals’ web sites may have different search functionalities, which do not necessarily yield a consistent output.

Q: Should I publish a protocol for my methodological study?

A: A protocol is a description of intended research methods. Currently, only protocols for clinical trials require registration [ 35 ]. Protocols for systematic reviews are encouraged but no formal recommendation exists. The scientific community welcomes the publication of protocols because they help protect against selective outcome reporting, the use of post hoc methodologies to embellish results, and to help avoid duplication of efforts [ 36 ]. While the latter two risks exist in methodological research, the negative consequences may be substantially less than for clinical outcomes. In a sample of 31 methodological studies, 7 (22.6%) referenced a published protocol [ 9 ]. In the Cochrane Library, there are 15 protocols for methodological reviews (21 July 2020). This suggests that publishing protocols for methodological studies is not uncommon.

Authors can consider publishing their study protocol in a scholarly journal as a manuscript. Advantages of such publication include obtaining peer-review feedback about the planned study, and easy retrieval by searching databases such as PubMed. The disadvantages in trying to publish protocols includes delays associated with manuscript handling and peer review, as well as costs, as few journals publish study protocols, and those journals mostly charge article-processing fees [ 37 ]. Authors who would like to make their protocol publicly available without publishing it in scholarly journals, could deposit their study protocols in publicly available repositories, such as the Open Science Framework ( https://osf.io/ ).

Q: How to appraise the quality of a methodological study?

A: To date, there is no published tool for appraising the risk of bias in a methodological study, but in principle, a methodological study could be considered as a type of observational study. Therefore, during conduct or appraisal, care should be taken to avoid the biases common in observational studies [ 38 ]. These biases include selection bias, comparability of groups, and ascertainment of exposure or outcome. In other words, to generate a representative sample, a comprehensive reproducible search may be necessary to build a sampling frame. Additionally, random sampling may be necessary to ensure that all the included research reports have the same probability of being selected, and the screening and selection processes should be transparent and reproducible. To ensure that the groups compared are similar in all characteristics, matching, random sampling or stratified sampling can be used. Statistical adjustments for between-group differences can also be applied at the analysis stage. Finally, duplicate data extraction can reduce errors in assessment of exposures or outcomes.

Q: Should I justify a sample size?

A: In all instances where one is not using the target population (i.e. the group to which inferences from the research report are directed) [ 39 ], a sample size justification is good practice. The sample size justification may take the form of a description of what is expected to be achieved with the number of articles selected, or a formal sample size estimation that outlines the number of articles required to answer the research question with a certain precision and power. Sample size justifications in methodological studies are reasonable in the following instances:

Comparing two groups

Determining a proportion, mean or another quantifier

Determining factors associated with an outcome using regression-based analyses

For example, El Dib et al. computed a sample size requirement for a methodological study of diagnostic strategies in randomized trials, based on a confidence interval approach [ 40 ].

Q: What should I call my study?

A: Other terms which have been used to describe/label methodological studies include “ methodological review ”, “methodological survey” , “meta-epidemiological study” , “systematic review” , “systematic survey”, “meta-research”, “research-on-research” and many others. We recommend that the study nomenclature be clear, unambiguous, informative and allow for appropriate indexing. Methodological study nomenclature that should be avoided includes “ systematic review” – as this will likely be confused with a systematic review of a clinical question. “ Systematic survey” may also lead to confusion about whether the survey was systematic (i.e. using a preplanned methodology) or a survey using “ systematic” sampling (i.e. a sampling approach using specific intervals to determine who is selected) [ 32 ]. Any of the above meanings of the words “ systematic” may be true for methodological studies and could be potentially misleading. “ Meta-epidemiological study” is ideal for indexing, but not very informative as it describes an entire field. The term “ review ” may point towards an appraisal or “review” of the design, conduct, analysis or reporting (or methodological components) of the targeted research reports, yet it has also been used to describe narrative reviews [ 41 , 42 ]. The term “ survey ” is also in line with the approaches used in many methodological studies [ 9 ], and would be indicative of the sampling procedures of this study design. However, in the absence of guidelines on nomenclature, the term “ methodological study ” is broad enough to capture most of the scenarios of such studies.

Q: Should I account for clustering in my methodological study?

A: Data from methodological studies are often clustered. For example, articles coming from a specific source may have different reporting standards (e.g. the Cochrane Library). Articles within the same journal may be similar due to editorial practices and policies, reporting requirements and endorsement of guidelines. There is emerging evidence that these are real concerns that should be accounted for in analyses [ 43 ]. Some cluster variables are described in the section: “ What variables are relevant to methodological studies?”

A variety of modelling approaches can be used to account for correlated data, including the use of marginal, fixed or mixed effects regression models with appropriate computation of standard errors [ 44 ]. For example, Kosa et al. used generalized estimation equations to account for correlation of articles within journals [ 15 ]. Not accounting for clustering could lead to incorrect p -values, unduly narrow confidence intervals, and biased estimates [ 45 ].

Q: Should I extract data in duplicate?

A: Yes. Duplicate data extraction takes more time but results in less errors [ 19 ]. Data extraction errors in turn affect the effect estimate [ 46 ], and therefore should be mitigated. Duplicate data extraction should be considered in the absence of other approaches to minimize extraction errors. However, much like systematic reviews, this area will likely see rapid new advances with machine learning and natural language processing technologies to support researchers with screening and data extraction [ 47 , 48 ]. However, experience plays an important role in the quality of extracted data and inexperienced extractors should be paired with experienced extractors [ 46 , 49 ].

Q: Should I assess the risk of bias of research reports included in my methodological study?

A : Risk of bias is most useful in determining the certainty that can be placed in the effect measure from a study. In methodological studies, risk of bias may not serve the purpose of determining the trustworthiness of results, as effect measures are often not the primary goal of methodological studies. Determining risk of bias in methodological studies is likely a practice borrowed from systematic review methodology, but whose intrinsic value is not obvious in methodological studies. When it is part of the research question, investigators often focus on one aspect of risk of bias. For example, Speich investigated how blinding was reported in surgical trials [ 50 ], and Abraha et al., investigated the application of intention-to-treat analyses in systematic reviews and trials [ 51 ].

Q: What variables are relevant to methodological studies?

A: There is empirical evidence that certain variables may inform the findings in a methodological study. We outline some of these and provide a brief overview below:

Country: Countries and regions differ in their research cultures, and the resources available to conduct research. Therefore, it is reasonable to believe that there may be differences in methodological features across countries. Methodological studies have reported loco-regional differences in reporting quality [ 52 , 53 ]. This may also be related to challenges non-English speakers face in publishing papers in English.

Authors’ expertise: The inclusion of authors with expertise in research methodology, biostatistics, and scientific writing is likely to influence the end-product. Oltean et al. found that among randomized trials in orthopaedic surgery, the use of analyses that accounted for clustering was more likely when specialists (e.g. statistician, epidemiologist or clinical trials methodologist) were included on the study team [ 54 ]. Fleming et al. found that including methodologists in the review team was associated with appropriate use of reporting guidelines [ 55 ].

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: Some studies have found that funded studies report better [ 56 , 57 ], while others do not [ 53 , 58 ]. The presence of funding would indicate the availability of resources deployed to ensure optimal design, conduct, analysis and reporting. However, the source of funding may introduce conflicts of interest and warrant assessment. For example, Kaiser et al. investigated the effect of industry funding on obesity or nutrition randomized trials and found that reporting quality was similar [ 59 ]. Thomas et al. looked at reporting quality of long-term weight loss trials and found that industry funded studies were better [ 60 ]. Kan et al. examined the association between industry funding and “positive trials” (trials reporting a significant intervention effect) and found that industry funding was highly predictive of a positive trial [ 61 ]. This finding is similar to that of a recent Cochrane Methodology Review by Hansen et al. [ 62 ]

Journal characteristics: Certain journals’ characteristics may influence the study design, analysis or reporting. Characteristics such as journal endorsement of guidelines [ 63 , 64 ], and Journal Impact Factor (JIF) have been shown to be associated with reporting [ 63 , 65 , 66 , 67 ].

Study size (sample size/number of sites): Some studies have shown that reporting is better in larger studies [ 53 , 56 , 58 ].

Year of publication: It is reasonable to assume that design, conduct, analysis and reporting of research will change over time. Many studies have demonstrated improvements in reporting over time or after the publication of reporting guidelines [ 68 , 69 ].

Type of intervention: In a methodological study of reporting quality of weight loss intervention studies, Thabane et al. found that trials of pharmacologic interventions were reported better than trials of non-pharmacologic interventions [ 70 ].

Interactions between variables: Complex interactions between the previously listed variables are possible. High income countries with more resources may be more likely to conduct larger studies and incorporate a variety of experts. Authors in certain countries may prefer certain journals, and journal endorsement of guidelines and editorial policies may change over time.

Q: Should I focus only on high impact journals?

A: Investigators may choose to investigate only high impact journals because they are more likely to influence practice and policy, or because they assume that methodological standards would be higher. However, the JIF may severely limit the scope of articles included and may skew the sample towards articles with positive findings. The generalizability and applicability of findings from a handful of journals must be examined carefully, especially since the JIF varies over time. Even among journals that are all “high impact”, variations exist in methodological standards.

Q: Can I conduct a methodological study of qualitative research?

A: Yes. Even though a lot of methodological research has been conducted in the quantitative research field, methodological studies of qualitative studies are feasible. Certain databases that catalogue qualitative research including the Cumulative Index to Nursing & Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) have defined subject headings that are specific to methodological research (e.g. “research methodology”). Alternatively, one could also conduct a qualitative methodological review; that is, use qualitative approaches to synthesize methodological issues in qualitative studies.

Q: What reporting guidelines should I use for my methodological study?

A: There is no guideline that covers the entire scope of methodological studies. One adaptation of the PRISMA guidelines has been published, which works well for studies that aim to use the entire target population of research reports [ 71 ]. However, it is not widely used (40 citations in 2 years as of 09 December 2019), and methodological studies that are designed as cross-sectional or before-after studies require a more fit-for purpose guideline. A more encompassing reporting guideline for a broad range of methodological studies is currently under development [ 72 ]. However, in the absence of formal guidance, the requirements for scientific reporting should be respected, and authors of methodological studies should focus on transparency and reproducibility.

Q: What are the potential threats to validity and how can I avoid them?

A: Methodological studies may be compromised by a lack of internal or external validity. The main threats to internal validity in methodological studies are selection and confounding bias. Investigators must ensure that the methods used to select articles does not make them differ systematically from the set of articles to which they would like to make inferences. For example, attempting to make extrapolations to all journals after analyzing high-impact journals would be misleading.

Many factors (confounders) may distort the association between the exposure and outcome if the included research reports differ with respect to these factors [ 73 ]. For example, when examining the association between source of funding and completeness of reporting, it may be necessary to account for journals that endorse the guidelines. Confounding bias can be addressed by restriction, matching and statistical adjustment [ 73 ]. Restriction appears to be the method of choice for many investigators who choose to include only high impact journals or articles in a specific field. For example, Knol et al. examined the reporting of p -values in baseline tables of high impact journals [ 26 ]. Matching is also sometimes used. In the methodological study of non-randomized interventional studies of elective ventral hernia repair, Parker et al. matched prospective studies with retrospective studies and compared reporting standards [ 74 ]. Some other methodological studies use statistical adjustments. For example, Zhang et al. used regression techniques to determine the factors associated with missing participant data in trials [ 16 ].

With regard to external validity, researchers interested in conducting methodological studies must consider how generalizable or applicable their findings are. This should tie in closely with the research question and should be explicit. For example. Findings from methodological studies on trials published in high impact cardiology journals cannot be assumed to be applicable to trials in other fields. However, investigators must ensure that their sample truly represents the target sample either by a) conducting a comprehensive and exhaustive search, or b) using an appropriate and justified, randomly selected sample of research reports.

Even applicability to high impact journals may vary based on the investigators’ definition, and over time. For example, for high impact journals in the field of general medicine, Bouwmeester et al. included the Annals of Internal Medicine (AIM), BMJ, the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), Lancet, the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM), and PLoS Medicine ( n = 6) [ 75 ]. In contrast, the high impact journals selected in the methodological study by Schiller et al. were BMJ, JAMA, Lancet, and NEJM ( n = 4) [ 76 ]. Another methodological study by Kosa et al. included AIM, BMJ, JAMA, Lancet and NEJM ( n = 5). In the methodological study by Thabut et al., journals with a JIF greater than 5 were considered to be high impact. Riado Minguez et al. used first quartile journals in the Journal Citation Reports (JCR) for a specific year to determine “high impact” [ 77 ]. Ultimately, the definition of high impact will be based on the number of journals the investigators are willing to include, the year of impact and the JIF cut-off [ 78 ]. We acknowledge that the term “generalizability” may apply differently for methodological studies, especially when in many instances it is possible to include the entire target population in the sample studied.

Finally, methodological studies are not exempt from information bias which may stem from discrepancies in the included research reports [ 79 ], errors in data extraction, or inappropriate interpretation of the information extracted. Likewise, publication bias may also be a concern in methodological studies, but such concepts have not yet been explored.

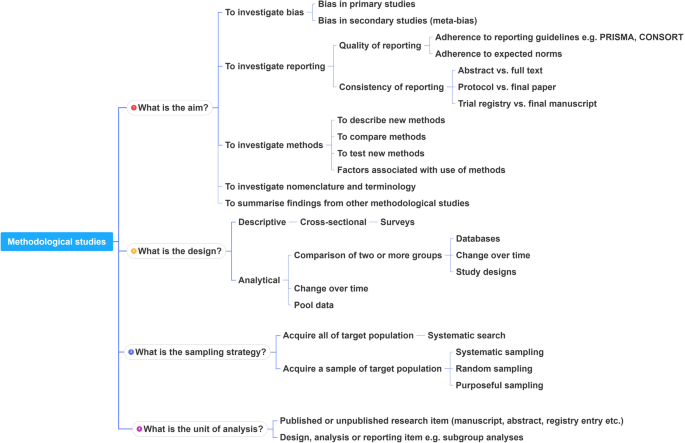

A proposed framework

In order to inform discussions about methodological studies, the development of guidance for what should be reported, we have outlined some key features of methodological studies that can be used to classify them. For each of the categories outlined below, we provide an example. In our experience, the choice of approach to completing a methodological study can be informed by asking the following four questions:

What is the aim?

Methodological studies that investigate bias

A methodological study may be focused on exploring sources of bias in primary or secondary studies (meta-bias), or how bias is analyzed. We have taken care to distinguish bias (i.e. systematic deviations from the truth irrespective of the source) from reporting quality or completeness (i.e. not adhering to a specific reporting guideline or norm). An example of where this distinction would be important is in the case of a randomized trial with no blinding. This study (depending on the nature of the intervention) would be at risk of performance bias. However, if the authors report that their study was not blinded, they would have reported adequately. In fact, some methodological studies attempt to capture both “quality of conduct” and “quality of reporting”, such as Richie et al., who reported on the risk of bias in randomized trials of pharmacy practice interventions [ 80 ]. Babic et al. investigated how risk of bias was used to inform sensitivity analyses in Cochrane reviews [ 81 ]. Further, biases related to choice of outcomes can also be explored. For example, Tan et al investigated differences in treatment effect size based on the outcome reported [ 82 ].

Methodological studies that investigate quality (or completeness) of reporting

Methodological studies may report quality of reporting against a reporting checklist (i.e. adherence to guidelines) or against expected norms. For example, Croituro et al. report on the quality of reporting in systematic reviews published in dermatology journals based on their adherence to the PRISMA statement [ 83 ], and Khan et al. described the quality of reporting of harms in randomized controlled trials published in high impact cardiovascular journals based on the CONSORT extension for harms [ 84 ]. Other methodological studies investigate reporting of certain features of interest that may not be part of formally published checklists or guidelines. For example, Mbuagbaw et al. described how often the implications for research are elaborated using the Evidence, Participants, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, Timeframe (EPICOT) format [ 30 ].

Methodological studies that investigate the consistency of reporting

Sometimes investigators may be interested in how consistent reports of the same research are, as it is expected that there should be consistency between: conference abstracts and published manuscripts; manuscript abstracts and manuscript main text; and trial registration and published manuscript. For example, Rosmarakis et al. investigated consistency between conference abstracts and full text manuscripts [ 85 ].

Methodological studies that investigate factors associated with reporting

In addition to identifying issues with reporting in primary and secondary studies, authors of methodological studies may be interested in determining the factors that are associated with certain reporting practices. Many methodological studies incorporate this, albeit as a secondary outcome. For example, Farrokhyar et al. investigated the factors associated with reporting quality in randomized trials of coronary artery bypass grafting surgery [ 53 ].

Methodological studies that investigate methods

Methodological studies may also be used to describe methods or compare methods, and the factors associated with methods. Muller et al. described the methods used for systematic reviews and meta-analyses of observational studies [ 86 ].

Methodological studies that summarize other methodological studies

Some methodological studies synthesize results from other methodological studies. For example, Li et al. conducted a scoping review of methodological reviews that investigated consistency between full text and abstracts in primary biomedical research [ 87 ].

Methodological studies that investigate nomenclature and terminology

Some methodological studies may investigate the use of names and terms in health research. For example, Martinic et al. investigated the definitions of systematic reviews used in overviews of systematic reviews (OSRs), meta-epidemiological studies and epidemiology textbooks [ 88 ].

Other types of methodological studies

In addition to the previously mentioned experimental methodological studies, there may exist other types of methodological studies not captured here.

What is the design?

Methodological studies that are descriptive

Most methodological studies are purely descriptive and report their findings as counts (percent) and means (standard deviation) or medians (interquartile range). For example, Mbuagbaw et al. described the reporting of research recommendations in Cochrane HIV systematic reviews [ 30 ]. Gohari et al. described the quality of reporting of randomized trials in diabetes in Iran [ 12 ].

Methodological studies that are analytical

Some methodological studies are analytical wherein “analytical studies identify and quantify associations, test hypotheses, identify causes and determine whether an association exists between variables, such as between an exposure and a disease.” [ 89 ] In the case of methodological studies all these investigations are possible. For example, Kosa et al. investigated the association between agreement in primary outcome from trial registry to published manuscript and study covariates. They found that larger and more recent studies were more likely to have agreement [ 15 ]. Tricco et al. compared the conclusion statements from Cochrane and non-Cochrane systematic reviews with a meta-analysis of the primary outcome and found that non-Cochrane reviews were more likely to report positive findings. These results are a test of the null hypothesis that the proportions of Cochrane and non-Cochrane reviews that report positive results are equal [ 90 ].

What is the sampling strategy?

Methodological studies that include the target population

Methodological reviews with narrow research questions may be able to include the entire target population. For example, in the methodological study of Cochrane HIV systematic reviews, Mbuagbaw et al. included all of the available studies ( n = 103) [ 30 ].

Methodological studies that include a sample of the target population

Many methodological studies use random samples of the target population [ 33 , 91 , 92 ]. Alternatively, purposeful sampling may be used, limiting the sample to a subset of research-related reports published within a certain time period, or in journals with a certain ranking or on a topic. Systematic sampling can also be used when random sampling may be challenging to implement.

What is the unit of analysis?

Methodological studies with a research report as the unit of analysis

Many methodological studies use a research report (e.g. full manuscript of study, abstract portion of the study) as the unit of analysis, and inferences can be made at the study-level. However, both published and unpublished research-related reports can be studied. These may include articles, conference abstracts, registry entries etc.

Methodological studies with a design, analysis or reporting item as the unit of analysis

Some methodological studies report on items which may occur more than once per article. For example, Paquette et al. report on subgroup analyses in Cochrane reviews of atrial fibrillation in which 17 systematic reviews planned 56 subgroup analyses [ 93 ].

This framework is outlined in Fig. 2 .

A proposed framework for methodological studies

Conclusions

Methodological studies have examined different aspects of reporting such as quality, completeness, consistency and adherence to reporting guidelines. As such, many of the methodological study examples cited in this tutorial are related to reporting. However, as an evolving field, the scope of research questions that can be addressed by methodological studies is expected to increase.

In this paper we have outlined the scope and purpose of methodological studies, along with examples of instances in which various approaches have been used. In the absence of formal guidance on the design, conduct, analysis and reporting of methodological studies, we have provided some advice to help make methodological studies consistent. This advice is grounded in good contemporary scientific practice. Generally, the research question should tie in with the sampling approach and planned analysis. We have also highlighted the variables that may inform findings from methodological studies. Lastly, we have provided suggestions for ways in which authors can categorize their methodological studies to inform their design and analysis.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Abbreviations

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials

Evidence, Participants, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, Timeframe

Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations

Participants, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, Timeframe

Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses

Studies Within a Review

Studies Within a Trial

Chalmers I, Glasziou P. Avoidable waste in the production and reporting of research evidence. Lancet. 2009;374(9683):86–9.

PubMed Google Scholar

Chan AW, Song F, Vickers A, Jefferson T, Dickersin K, Gotzsche PC, Krumholz HM, Ghersi D, van der Worp HB. Increasing value and reducing waste: addressing inaccessible research. Lancet. 2014;383(9913):257–66.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Ioannidis JP, Greenland S, Hlatky MA, Khoury MJ, Macleod MR, Moher D, Schulz KF, Tibshirani R. Increasing value and reducing waste in research design, conduct, and analysis. Lancet. 2014;383(9912):166–75.

Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, Juni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, Savovic J, Schulz KF, Weeks L, Sterne JA. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928.

Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG. The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomised trials. Lancet. 2001;357.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000100.

Shea BJ, Hamel C, Wells GA, Bouter LM, Kristjansson E, Grimshaw J, Henry DA, Boers M. AMSTAR is a reliable and valid measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):1013–20.

Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, Moher D, Tugwell P, Welch V, Kristjansson E, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. Bmj. 2017;358:j4008.

Lawson DO, Leenus A, Mbuagbaw L. Mapping the nomenclature, methodology, and reporting of studies that review methods: a pilot methodological review. Pilot Feasibility Studies. 2020;6(1):13.

Puljak L, Makaric ZL, Buljan I, Pieper D. What is a meta-epidemiological study? Analysis of published literature indicated heterogeneous study designs and definitions. J Comp Eff Res. 2020.

Abbade LPF, Wang M, Sriganesh K, Jin Y, Mbuagbaw L, Thabane L. The framing of research questions using the PICOT format in randomized controlled trials of venous ulcer disease is suboptimal: a systematic survey. Wound Repair Regen. 2017;25(5):892–900.

Gohari F, Baradaran HR, Tabatabaee M, Anijidani S, Mohammadpour Touserkani F, Atlasi R, Razmgir M. Quality of reporting randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in diabetes in Iran; a systematic review. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2015;15(1):36.

Wang M, Jin Y, Hu ZJ, Thabane A, Dennis B, Gajic-Veljanoski O, Paul J, Thabane L. The reporting quality of abstracts of stepped wedge randomized trials is suboptimal: a systematic survey of the literature. Contemp Clin Trials Commun. 2017;8:1–10.

Shanthanna H, Kaushal A, Mbuagbaw L, Couban R, Busse J, Thabane L: A cross-sectional study of the reporting quality of pilot or feasibility trials in high-impact anesthesia journals Can J Anaesthesia 2018, 65(11):1180–1195.

Kosa SD, Mbuagbaw L, Borg Debono V, Bhandari M, Dennis BB, Ene G, Leenus A, Shi D, Thabane M, Valvasori S, et al. Agreement in reporting between trial publications and current clinical trial registry in high impact journals: a methodological review. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2018;65:144–50.

Zhang Y, Florez ID, Colunga Lozano LE, Aloweni FAB, Kennedy SA, Li A, Craigie S, Zhang S, Agarwal A, Lopes LC, et al. A systematic survey on reporting and methods for handling missing participant data for continuous outcomes in randomized controlled trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;88:57–66.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Hernández AV, Boersma E, Murray GD, Habbema JD, Steyerberg EW. Subgroup analyses in therapeutic cardiovascular clinical trials: are most of them misleading? Am Heart J. 2006;151(2):257–64.

Samaan Z, Mbuagbaw L, Kosa D, Borg Debono V, Dillenburg R, Zhang S, Fruci V, Dennis B, Bawor M, Thabane L. A systematic scoping review of adherence to reporting guidelines in health care literature. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2013;6:169–88.

Buscemi N, Hartling L, Vandermeer B, Tjosvold L, Klassen TP. Single data extraction generated more errors than double data extraction in systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006;59(7):697–703.

Carrasco-Labra A, Brignardello-Petersen R, Santesso N, Neumann I, Mustafa RA, Mbuagbaw L, Etxeandia Ikobaltzeta I, De Stio C, McCullagh LJ, Alonso-Coello P. Improving GRADE evidence tables part 1: a randomized trial shows improved understanding of content in summary-of-findings tables with a new format. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;74:7–18.

The Northern Ireland Hub for Trials Methodology Research: SWAT/SWAR Information [ https://www.qub.ac.uk/sites/TheNorthernIrelandNetworkforTrialsMethodologyResearch/SWATSWARInformation/ ]. Accessed 31 Aug 2020.

Chick S, Sánchez P, Ferrin D, Morrice D. How to conduct a successful simulation study. In: Proceedings of the 2003 winter simulation conference: 2003; 2003. p. 66–70.

Google Scholar

Mulrow CD. The medical review article: state of the science. Ann Intern Med. 1987;106(3):485–8.

Sacks HS, Reitman D, Pagano D, Kupelnick B. Meta-analysis: an update. Mount Sinai J Med New York. 1996;63(3–4):216–24.

CAS Google Scholar

Areia M, Soares M, Dinis-Ribeiro M. Quality reporting of endoscopic diagnostic studies in gastrointestinal journals: where do we stand on the use of the STARD and CONSORT statements? Endoscopy. 2010;42(2):138–47.

Knol M, Groenwold R, Grobbee D. P-values in baseline tables of randomised controlled trials are inappropriate but still common in high impact journals. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2012;19(2):231–2.

Chen M, Cui J, Zhang AL, Sze DM, Xue CC, May BH. Adherence to CONSORT items in randomized controlled trials of integrative medicine for colorectal Cancer published in Chinese journals. J Altern Complement Med. 2018;24(2):115–24.

Hopewell S, Ravaud P, Baron G, Boutron I. Effect of editors' implementation of CONSORT guidelines on the reporting of abstracts in high impact medical journals: interrupted time series analysis. BMJ. 2012;344:e4178.

The Cochrane Methodology Register Issue 2 2009 [ https://cmr.cochrane.org/help.htm ]. Accessed 31 Aug 2020.

Mbuagbaw L, Kredo T, Welch V, Mursleen S, Ross S, Zani B, Motaze NV, Quinlan L. Critical EPICOT items were absent in Cochrane human immunodeficiency virus systematic reviews: a bibliometric analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;74:66–72.

Barton S, Peckitt C, Sclafani F, Cunningham D, Chau I. The influence of industry sponsorship on the reporting of subgroup analyses within phase III randomised controlled trials in gastrointestinal oncology. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51(18):2732–9.

Setia MS. Methodology series module 5: sampling strategies. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61(5):505–9.

Wilson B, Burnett P, Moher D, Altman DG, Al-Shahi Salman R. Completeness of reporting of randomised controlled trials including people with transient ischaemic attack or stroke: a systematic review. Eur Stroke J. 2018;3(4):337–46.

Kahale LA, Diab B, Brignardello-Petersen R, Agarwal A, Mustafa RA, Kwong J, Neumann I, Li L, Lopes LC, Briel M, et al. Systematic reviews do not adequately report or address missing outcome data in their analyses: a methodological survey. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018;99:14–23.

De Angelis CD, Drazen JM, Frizelle FA, Haug C, Hoey J, Horton R, Kotzin S, Laine C, Marusic A, Overbeke AJPM, et al. Is this clinical trial fully registered?: a statement from the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors*. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143(2):146–8.

Ohtake PJ, Childs JD. Why publish study protocols? Phys Ther. 2014;94(9):1208–9.

Rombey T, Allers K, Mathes T, Hoffmann F, Pieper D. A descriptive analysis of the characteristics and the peer review process of systematic review protocols published in an open peer review journal from 2012 to 2017. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2019;19(1):57.

Grimes DA, Schulz KF. Bias and causal associations in observational research. Lancet. 2002;359(9302):248–52.

Porta M (ed.): A dictionary of epidemiology, 5th edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press, Inc.; 2008.

El Dib R, Tikkinen KAO, Akl EA, Gomaa HA, Mustafa RA, Agarwal A, Carpenter CR, Zhang Y, Jorge EC, Almeida R, et al. Systematic survey of randomized trials evaluating the impact of alternative diagnostic strategies on patient-important outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;84:61–9.

Helzer JE, Robins LN, Taibleson M, Woodruff RA Jr, Reich T, Wish ED. Reliability of psychiatric diagnosis. I. a methodological review. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1977;34(2):129–33.

Chung ST, Chacko SK, Sunehag AL, Haymond MW. Measurements of gluconeogenesis and Glycogenolysis: a methodological review. Diabetes. 2015;64(12):3996–4010.

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar