Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 23 June 2020

The high cost of prescription drugs: causes and solutions

- S. Vincent Rajkumar ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5862-1833 1

Blood Cancer Journal volume 10 , Article number: 71 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

102k Accesses

71 Citations

279 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Cancer therapy

- Public health

Global spending on prescription drugs in 2020 is expected to be ~$1.3 trillion; the United States alone will spend ~$350 billion 1 . These high spending rates are expected to increase at a rate of 3–6% annually worldwide. The magnitude of increase is even more alarming for cancer treatments that account for a large proportion of prescription drug costs. In 2018, global spending on cancer treatments was approximately 150 billion, and has increased by >10% in each of the past 5 years 2 .

The high cost of prescription drugs threatens healthcare budgets, and limits funding available for other areas in which public investment is needed. In countries without universal healthcare, the high cost of prescription drugs poses an additional threat: unaffordable out-of-pocket costs for individual patients. Approximately 25% of Americans find it difficult to afford prescription drugs due to high out-of-pocket costs 3 . Drug companies cite high drug prices as being important for sustaining innovation. But the ability to charge high prices for every new drug possibly slows the pace of innovation. It is less risky to develop drugs that represent minor modifications of existing drugs (“me-too” drugs) and show incremental improvement in efficacy or safety, rather than investing in truly innovative drugs where there is a greater chance of failure.

Causes for the high cost of prescription drugs

The most important reason for the high cost of prescription drugs is the existence of monopoly 4 , 5 . For many new drugs, there are no other alternatives. In the case of cancer, even when there are multiple drugs to treat a specific malignancy, there is still no real competition based on price because most cancers are incurable, and each drug must be used in sequence for a given patient. Patients will need each effective drug at some point during the course of their disease. There is seldom a question of whether a new drug will be needed, but only when it will be needed. Even some old drugs can remain as virtual monopolies. For example, in the United States, three companies, NovoNordisk, Sanofi-Aventis, and Eli Lilly control most of the market for insulin, contributing to high prices and lack of competition 6 .

Ideally, monopolies will be temporary because eventually generic competition should emerge as patents expire. Unfortunately, in cancers and chronic life-threatening diseases, this often does not happen. By the time a drug runs out of patent life, it is already considered obsolete (planned obsolescence) and is no longer the standard of care 4 . A “new and improved version” with a fresh patent life and monopoly protection has already taken the stage. In the case of biologic drugs, cumbersome manufacturing and biosimilar approval processes are additional barriers that greatly limit the number of competitors that can enter the market.

Clearly, all monopolies need to be regulated in order to protect citizens, and therefore most of the developed world uses some form of regulations to cap the launch prices of new prescription drugs. Unregulated monopolies pose major problems. Unregulated monopoly over an essential product can lead to unaffordable prices that threaten the life of citizens. This is the case in the United States, where there are no regulations to control prescription drug prices and no enforceable mechanisms for value-based pricing.

Seriousness of the disease

High prescription drug prices are sustained by the fact that treatments for serious disease are not luxury items, but are needed by vulnerable patients who seek to improve the quality of life or to prolong life. A high price is not a barrier. For serious diseases, patients and their families are willing to pay any price in order to save or prolong life.

High cost of development

Drug development is a long and expensive endeavor: it takes about 12 years for a drug to move from preclinical testing to final approval. It is estimated that it costs approximately $3 billion to develop a new drug, taking into account the high failure rate, wherein only 10–20% of drugs tested are successful and reach the market 7 . Although the high cost of drug development is a major issue that needs to be addressed, some experts consider these estimates to be vastly inflated 8 , 9 . Further, the costs of development are inversely proportional to the incremental benefit provided by the new drug, since it takes trials with a larger sample size, and a greater number of trials to secure regulatory approval. More importantly, we cannot ignore the fact that a considerable amount of public funding goes into the science behind most new drugs, and the public therefore does have a legitimate right in making sure that life-saving drugs are priced fairly.

Lobbying power of pharmaceutical companies

Individual pharmaceutical companies and their trade organization spent approximately $220 million in lobbying in the United States in 2018 10 . Although nations recognize the major problems posed by high prescription drug prices, little has been accomplished in terms of regulatory or legislative reform because of the lobbying power of the pharmaceutical and healthcare industry.

Solutions: global policy changes

There are no easy solutions to the problem of high drug prices. The underlying reasons are complex; some are unique to the United States compared with the rest of the world (Table 1 ).

Patent reform

One of the main ways to limit the problem posed by monopoly is to limit the duration of patent protection. Current patent protections are too long, and companies apply for multiple new patents on the same drug in order to prolong monopoly. We need to reform the patent system to prevent overpatenting and patent abuse 11 . Stiff penalties are needed to prevent “pay-for-delay” schemes where generic competitors are paid money to delay market entry 12 . Patent life should be fixed, and not exceed 7–10 years from the date of first entry into the market (one-and-done approach) 13 . These measures will greatly stimulate generic and biosimilar competition.

Faster approval of generics and biosimilars

The approval process for generics and biosimilars must be simplified. A reciprocal regulatory approval process among Western European countries, the United States, Canada, and possibly other developed countries, can greatly reduce the redundancies 14 . In such a system, prescription drugs approved in one member country can automatically be granted regulatory approval in the others, greatly simplifying the regulatory process. This requires the type of trust, shared standards, and cooperation that we currently have with visa-free travel and trusted traveler programs 6 .

For complex biologic products, such as insulin, it is impossible to make the identical product 15 . The term “biosimilars” is used (instead of “generics”) for products that are almost identical in composition, pharmacologic properties, and clinical effects. Biosimilar approval process is more cumbersome, and unlike generics requires clinical trials prior to approval. Further impediments to the adoption of biosimilars include reluctance on the part of providers to trust a biosimilar, incentives offered by the manufacturer of the original biologic, and lawsuits to prevent market entry. It is important to educate providers on the safety of biosimilars. A comprehensive strategy to facilitate the timely entry of cost-effective biosimilars can also help lower cost. In the United States, the FDA has approved 23 biosimilars. Success is mixed due to payer arrangements, but when optimized, these can be very successful. For example, in the case of filgrastim, there is over 60% adoption of the biosimilar, with a cost discount of approximately 30–40% 16 .

Nonprofit generic companies

One way of lowering the cost of prescription drugs and to reduce drug shortages is nonprofit generic manufacturing. This can be set up and run by governments, or by nonprofit or philanthropic foundations. A recent example of such an endeavor is Civica Rx, a nonprofit generic company that has been set up in the United States.

Compulsory licensing

Developed countries should be more willing to use compulsory licensing to lower the cost of specific prescription drugs when negotiations with drug manufacturers on reasonable pricing fail or encounter unacceptable delays. This process permitted under the Doha declaration of 2001, allows countries to override patent protection and issue a license to manufacture and distribute a given prescription drug at low cost in the interest of public health.

Solutions: additional policy changes needed in the United States

The cost of prescription drugs in the United States is much higher than in other developed countries. The reasons for these are unique to the United States, and require specific policy changes.

Value-based pricing

Unlike other developed countries, the United States does not negotiate over the price of a new drug based on the value it provides. This is a fundamental problem that allows drugs to be priced at high levels, regardless of the value that they provide. Thus, almost every new cancer drug introduced in the last 3 years has been priced at more than $100,000 per year, with a median price of approximately $150,000 in 2018. The lack of value-based pricing in the United States also has a direct adverse effect on the ability of other countries to negotiate prices with manufacturers . It greatly reduces leverage that individual countries have. Manufacturers can walk away from such negotiations, knowing fully well that they can price the drugs in the United States to compensate. A governmental or a nongovernmental agency, such as the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER), must be authorized in the United States by law, to set ceiling prices for new drugs based on incremental value, and monitor and approve future price increases. Until this is possible, the alternative solution is to cap prices of lifesaving drugs to an international reference price.

Medicare negotiation

In addition to not having a system for value-based pricing, the United States has specific legislation that actually prohibits the biggest purchaser of oral prescription drugs (Medicare) from directly negotiating with manufacturers. One study found that if Medicare were to negotiate prices to those secured by the Veterans Administration (VA) hospital system, there would be savings of $14.4 billion on just the top 50 dispensed oral drugs 17 .

Cap on price increases

The United States also has a peculiar problem that is not seen in other countries: marked price increases on existing drugs. For example, between 2012 and 2017, the United States spent $6.8 billion solely due to price increases on the existing brand name cancer drugs; in the same period, the rest of the world spent $1.7 billion less due to decreases in the prices of similar drugs 18 . But nothing illustrates this problem better than the price of insulin 19 . One vial of Humalog (insulin lispro), that costs $21 in 1999, is now priced at over $300. On January 1, 2020, drugmakers increased prices on over 250 drugs by approximately 5% 20 . The United States clearly needs state and/or federal legislation to prevent such unjustified price increases 21 .

Remove incentive for more expensive therapy

Doctors in the United States receive a proportionally higher reimbursement for parenteral drugs, including intravenous chemotherapy, for more expensive drugs. This creates a financial incentive to choosing a more expensive drug when there is a choice for a cheaper alternative. We need to reform physician reimbursement to a model where the amount paid for drug administration is fixed, and not proportional to the cost of the drug.

Other reforms

We need transparency on arrangements between middlemen, such as pharmacy-benefit managers (PBMs) and drug manufacturers, and ensure that rebates on drug prices secured by PBMS do not serve as profits, but are rather passed on to patients. Drug approvals should encourage true innovation, and approval of marginally effective drugs with statistically “significant” but clinically unimportant benefits should be discouraged. Importation of prescription drugs for personal use should be legalized. Finally, we need to end direct-to-patient advertising.

Solutions that can be implemented by physicians and physician organizations

Most of the changes discussed above require changes to existing laws and regulations, and physicians and physician organizations should be advocating for these changes. It is disappointing that there is limited advocacy in this regard for changes that can truly have an impact. The close financial relationships of physician and patient organizations with pharmaceutical companies may be preventing us from effective advocacy. We also need to generate specific treatment guidelines that take cost into account. Current guidelines often present a list of acceptable treatment options for a given condition, without clear recommendation that guides patients and physicians to choose the most cost=effective option. Prices of common prescription drugs can vary markedly in the United States, and physicians can help patients by directing them to the pharmacy with the lowest prices using resources such as goodrx.com 22 . Physicians must become more educated on drug prices, and discuss affordability with patients 23 .

IQVIA. The global use of medicine in 2019 and outlook to 2023. https://www.iqvia.com/insights/the-iqvia-institute/reports/the-global-use-of-medicine-in-2019-and-outlook-to-2023 (Accessed December 27, 2019).

IQVIA. Global oncology trends 2019. https://www.iqvia.com/insights/the-iqvia-institute/reports/global-oncology-trends-2019 (Accessed December 27, 2019).

Kamal, R., Cox, C. & McDermott, D. What are the recent and forecasted trends in prescription drug spending? https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/chart-collection/recent-forecasted-trends-prescription-drug-spending/#item-percent-of-total-rx-spending-by-oop-private-insurance-and-medicare_nhe-projections-2018-27 (Accessed December 31, 2019).

Siddiqui, M. & Rajkumar, S. V. The high cost of cancer drugs and what we can do about it. Mayo Clinic Proc. 87 , 935–943 (2012).

Article Google Scholar

Kantarjian, H. & Rajkumar, S. V. Why are cancer drugs so expensive in the United States, and what are the solutions? Mayo Clinic Proc. 90 , 500–504 (2015).

Rajkumar, S. V. The high cost of insulin in the united states: an urgent call to action. Mayo Clin. Proc. ; this issue (2020).

DiMasi, J. A., Grabowski, H. G. & Hansen, R. W. Innovation in the pharmaceutical industry: new estimates of R&D costs. J. Health Econ. 47 , 20–33 (2016).

Almashat, S. Pharmaceutical research costs: the myth of the $2.6 billion pill. https://www.citizen.org/news/pharmaceutical-research-costs-the-myth-of-the-2-6-billion-pill/ (Accessed December 31, 2019) (2017).

Prasad, V. & Mailankody, S. Research and development spending to bring a single cancer drug to market and revenues after approval. JAMA Intern. Med. 177 , 1569–1575 (2017).

Scutti, S. Big Pharma spends record millions on lobbying amid pressure to lower drug prices. https://www.cnn.com/2019/01/23/health/phrma-lobbying-costs-bn/index.html (Accessed December 31, 2019).

Amin, T. Patent abuse is driving up drug prices. https://www.statnews.com/2018/12/07/patent-abuse-rising-drug-prices-lantus/ (Accessed November 16, 2019).

Hancock, J. & Lupkin, S. Secretive ‘rebate trap’ keeps generic drugs for diabetes and other ills out of reach. https://khn.org/news/secretive-rebate-trap-keeps-generic-drugs-for-diabetes-and-other-ills-out-of-reach/ (Accessed November 16, 2019).

Feldman, R. ‘One-and-done’ for new drugs could cut patent thickets and boost generic competition. https://www.statnews.com/2019/02/11/drug-patent-protection-one-done/ (Accessed December 31, 2019).

Cohen, M. et al. Policy options for increasing generic drug competition through importation. Health Affairs Blog https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20190103.333047/full/ (Accessed November 16, 2019).

Bennett, C. L. et al. Regulatory and clinical considerations for biosimilar oncology drugs. Lancet Oncol 15 , e594–e605 (2014).

Fein, A. J. We shouldn’t give up on biosimilars—and here are the data to prove it. https://www.drugchannels.net/2019/09/we-shouldnt-give-up-on-biosimilarsand.html (Accessed December 31, 2019).

Venker, B., Stephenson, K. B. & Gellad, W. F. Assessment of spending in medicare part D if medication prices from the department of veterans affairs were used. JAMA Intern. Med. 179 , 431–433 (2019).

IQVIA. Global oncology trends 2018. https://www.iqvia.com/insights/the-iqvia-institute/reports/global-oncology-trends-2018 (Accessed January 2, 2018).

Prasad, R. The human cost of insulin in America. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-47491964 (Accessed November 16, 2019).

Erman, M. More drugmakers hike U.S. prices as new year begins. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-healthcare-drugpricing/more-drugmakers-hike-u-s-prices-as-new-year-begins-idUSKBN1Z01X9 (Accessed January 3, 2020).

Anderson, G. F. It’s time to limit drug price increases. Health Affairs Blog. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20190715.557473/full/ (Accessed November 16, 2019).

Gill, L. Shop around for lower drug prices. Consumer Reports 2018. https://www.consumerreports.org/drug-prices/shop-around-for-better-drug-prices/ (Accessed November 16, 2019).

Warsame, R. et al. Conversations about financial issues in routine oncology practices: a multicenter study. J. Oncol. Pract. 15 , e690–e703 (2019).

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

The Division of Hematology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA

S. Vincent Rajkumar

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to S. Vincent Rajkumar .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The author declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supported in part by grants CA 107476, CA 168762, and CA186781 from the National Cancer Institute, Rockville, MD, USA.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Vincent Rajkumar, S. The high cost of prescription drugs: causes and solutions. Blood Cancer J. 10 , 71 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-020-0338-x

Download citation

Received : 23 April 2020

Revised : 08 June 2020

Accepted : 10 June 2020

Published : 23 June 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-020-0338-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Prescription opioid use and misuse among adolescents and young adults in the United States: A national survey study

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliations Division of Emergency Medicine, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, United States of America, Departments of Pediatrics and Emergency Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, United States of America

Roles Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Division of Emergency Medicine, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, United States of America

Roles Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Software, Writing – review & editing

Roles Conceptualization, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations Division of Emergency Medicine, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, United States of America, Departments of Pediatrics and Emergency Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, United States of America, Pediatric Therapeutics and Regulatory Science Initiative, Computational Health Informatics Program, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, United States of America

- Joel D. Hudgins,

- John J. Porter,

- Michael C. Monuteaux,

- Florence T. Bourgeois

- Published: November 5, 2019

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002922

- Reader Comments

Prescription opioid misuse has become a leading cause of unintentional injury and death among adolescents and young adults in the United States. However, there is limited information on how adolescents and young adults obtain prescription opioids. There are also inadequate recent data on the prevalence of additional drug abuse among those misusing prescription opioids. In this study, we evaluated past-year prevalence of prescription opioid use and misuse, sources of prescription opioids, and additional substance use among adolescents and young adults.

Methods and findings

This was a retrospective analysis of the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) for the years 2015 and 2016. Prevalence of opioid use, misuse, use disorder, and additional substance use were calculated with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), stratified by age group and other demographic variables. Sources of prescription opioids were determined for respondents reporting opioid misuse. We calculated past-year prevalence of opioid use and misuse with or without use disorder, sources of prescription opioids, and prevalence of additional substance use. We included 27,857 adolescents (12–17 years of age) and 28,213 young adults (18–25 years of age) in our analyses, corresponding to 119.3 million individuals in the extrapolated national population. There were 15,143 respondents (27.5% [95% CI 27.0–28.0], corresponding to 32.8 million individuals) who used prescription opioids in the previous year, including 21.0% (95% CI 20.4–21.6) of adolescents and 32.2% (95% CI 31.4–33.0) of young adults. Significantly more females than males reported using any prescription opioid (30.3% versus 24.8%, P < 0.001), and non-Hispanic whites and blacks were more likely to have had any opioid use compared to Hispanics (28.9%, 28.1%, and 25.8%, respectively; P < 0.001). Opioid misuse was reported by 1,050 adolescents (3.8%; 95% CI 3.5–4.0) and 2,207 young adults (7.8%; 95% CI 7.3–8.2; P < 0.001). Male respondents using opioids were more likely to have opioid misuse without use disorder compared with females (23.2% versus 15.8%, respectively; P < 0.001), with similar prevalence by race/ethnicity. Among those misusing opioids, 55.7% obtained them from friends or relatives, 25.4% from the healthcare system, and 18.9% through other means. Obtaining opioids free from friends or relatives was the most common source for both adolescents (33.5%) and young adults (41.4%). Those with opioid misuse reported high prevalence of prior cocaine (35.5%), hallucinogen (49.4%), heroin (8.7%), and inhalant (30.4%) use. In addition, at least half had used tobacco (55.5%), alcohol (66.9%), or cannabis (49.9%) in the past month. Potential limitations of the study are that we cannot exclude selection bias in the study design or socially desirable reporting among participants, and that longitudinal data are not available for long-term follow-up of individuals.

Conclusions

Results from this study suggest that the prevalence of prescription opioid use among adolescents and young adults in the US is high despite known risks for future opioid and other drug use disorders. Reported prescription opioid misuse is common among adolescents and young adults and often associated with additional substance abuse, underscoring the importance of drug and alcohol screening programs in this population. Prevention and treatment efforts should take into account that greater than half of youths misusing prescription opioids obtain these medications through friends and relatives.

Author summary

Why was this study done.

- Prescription opioid misuse is a leading cause of unintentional injury and death among adolescents and young adults.

- There is limited information on the source of prescription opioids among adolescents and young adults or whether those misusing prescription opioids engage in use of additional substances and drugs of abuse.

- Understanding these factors will inform strategies to ensure judicious opioid prescribing and effective treatment approaches.

What did the researchers do and find?

- Using the National Survey on Drug Use and Health for the years 2015 and 2016, we determined past-year prevalence of prescription opioid use, sources of prescription opioids, and additional substance use among adolescents and young adults ages 12–25.

- We found that 27.5% of respondents, corresponding to an estimated 32.8 million individuals, used prescription opioids in the previous year, including 21.0% of adolescents and 32.2% of young adults.

- The prevalence of opioid misuse was 3.8% among adolescents and 7.8% among young adults.

- Most individuals misusing prescription opioids obtained them for free from a friend or relative or from a single prescriber.

- Individuals with prescription opioid misuse reported high prevalence of use of other substances, including cocaine, hallucinogens, heroin, and inhalants.

What do these findings mean?

- The prevalence of prescription opioid use is high among adolescents and young adults in the United States despite known risks for progression to opioid and other substance use disorders in this population.

- Prevention and treatment efforts should take into account that adolescents and young adults misusing prescription opioids obtain these drugs most commonly from friends and relatives or from a single prescriber.

- Healthcare providers should consider screening all adolescents and young adults with opioid misuse for additional substance use and should have established intervention plans available to maximize the opportunity to provide substance use treatment to this population.

Citation: Hudgins JD, Porter JJ, Monuteaux MC, Bourgeois FT (2019) Prescription opioid use and misuse among adolescents and young adults in the United States: A national survey study. PLoS Med 16(11): e1002922. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002922

Academic Editor: Margarita Alegria, Massachusetts General Hospital, UNITED STATES

Received: May 5, 2019; Accepted: September 25, 2019; Published: November 5, 2019

Copyright: © 2019 Hudgins et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: The data underlying the results presented in the study are available from https://datafiles.samhsa.gov/study-dataset/national-survey-drug-use-and-health-2016-nsduh-2016-ds0001-nid17185 and https://datafiles.samhsa.gov/study-dataset/national-survey-drug-use-and-health-2015-nsduh-2015-ds0001-nid16894 .

Funding: FTB is supported by the Burroughs Wellcome Fund ( https://www.bwfund.org/ ), grant number 1017627. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; DSM-IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders , 4th edition; NSDUH, National Survey on Drug Use and Health; PMN, predictive mean neighborhood; SAMHSA, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration

Introduction

Over the past two decades, opioid misuse and poisonings have emerged as a public health crisis in the US. Since 1999, rates of deaths secondary to opioids have tripled, and in 2017 alone, over 72,000 Americans died from opioid overdoses [ 1 , 2 ]. Children and adolescents have not been spared, with substantial increases over the past two decades in opioid-related emergency department visits, hospital and intensive care unit admissions, and deaths [ 3 – 6 ]. Opioid exposures accounted for over 12% of all deaths in 2016 among 15- to 24-year-olds, which represents a 4-fold increase since 2001 [ 7 ]. According to the Centers for Disease Control’s 2018 National Vital Statistics report, unintentional injuries are now the leading cause of death among adolescents and young adults, with poisonings the most common unintentional injury [ 8 , 9 ].

Among adults in the US, roughly 1 in 3 is estimated to use prescription opioids, with 4.7%, or 11.5 million, misusing them [ 10 ]. Opioid misuse in adults has been linked to several risk factors, including mood and anxiety disorders, male gender, educational attainment, and age at first misuse [ 11 – 13 ]. Among adolescents and young adults, data are sparser and less consistent, although prevalence of opioid use disorder appears to be steadily increasing [ 14 , 15 ]. A recent meta-analysis examining past-year prevalence of prescription opioid misuse among adolescents and young adults reported estimates ranging from 0.7% to 16.3% [ 16 ]. Two of the largest adolescent drug surveys in the US are the Youth Risk Behavior Survey, which asks about misuse of “pain medications” broadly, and Monitoring the Future, which asks about misuse of “narcotics other than heroin” [ 17 , 18 ]. These studies report lifetime prevalence of misuse of 17.0% and 6.8%, respectively, among 12th grade students in 2017. Risk factors identified among adolescents include earlier onset of use, educational attainment, and chronic pain, although these links are less robust than in adult studies [ 19 – 21 ]. Importantly, legitimate use of opioids during adolescence appears to predispose to later opioid misuse [ 19 , 22 ].

There is limited information on how adolescents and young adults are obtaining prescription opioids. Studies suggest an indirect link between opioid prescriptions in adults and exposures in adolescents, suggesting that households and family members may be a contributing source [ 23 , 24 ]. In one survey study conducted from 2008 to 2011, parents and friends from school were identified as the most common sources of prescription opioids for adolescents [ 25 ].

In this study, we analyzed data from a large, nationally representative survey collecting information on prescription opioids to measure prevalence of opioid use and misuse among US adolescents and young adults. We also determined sources of prescription opioids and characterized opioid use and misuse according to additional use of other substances and drugs of abuse.

Survey methods

Data for this analysis were obtained from survey responses in the 2015 and 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH). The NSDUH is an annual cross-sectional survey that collects information on drug use, mental health, and other health-related issues in the US civilian, noninstitutionalized population aged 12 years and older. It is sponsored by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) within the US Department of Health and Human Services. We used the publicly available version of the dataset, which was downloaded for use on February 16, 2018.

The survey includes interviews with approximately 70,000 individuals randomly selected annually, using a multistage area probability sample for each state and the District of Columbia. Certain populations, including younger age groups (i.e., 12 to 25 years), are oversampled to ensure robust estimates [ 26 ]. Interviews are conducted in the individual’s residence by a trained interviewer after verbal informed consent has been obtained. Data are collected using computer-assisted personal interviewing, in which the interviewer reads a question to the participant and enters the response into the computer. For questions on illicit drug use and other sensitive behaviors, a more private approach is used with audio computer-assisted self-interviewing, enabling respondents to read or listen to a question on headphones and enter the response into the computer themselves [ 26 ]. Respondents receive a $30 compensation for their participation. Additional information on the NSDUH sample design and survey methodology is available in the SAMHSA annual reports [ 26 ].

Our analysis was prospectively planned, including the definition of the study population, sociodemographic characteristics of interest, and outcome measures. Two modifications were made to the planned analysis. The first was our definition of young adult, which we initially defined as 18–23 years of age but modified to 18–25 years to match the NSDUH definition and data categorization. The second was the grouping of the different sources of prescription opioids, which was revised in response to peer-review comments. The study was deemed exempt from review by the Institutional Review Board at Boston Children’s Hospital.

Study population

We analyzed responses from adolescents 12 to 17 years of age and young adults 18 to 25 years of age. The NSDUH seeks to allocate 25% of its sample to adolescents aged 12 to 17 years, 25% to young adults aged 18 to 25 years, and the remaining 50% to adults 26 years and older [ 26 ]. The actual percentages of adolescents and young adults participating in 2015 were 23.1% and 24.6%, respectively, and in 2016, 23.3% and 23.9%, respectively [ 26 ]. The weighted interview response rates for adolescents and young adults were 77.7% and 74.4%, respectively, in 2015, and 77.0% and 72.3%, respectively, in 2016. By comparison, weighted interview response rates for adults were 67.4% in 2015 and 66.7% in 2016. All respondents were sampled independently. During the study period, less than 1% of respondents in our population were re-sampled in successive years. Each sampled observation is weighted within the context of the sampling frame for the given year, regardless of whether the observation represents a repeated record on the same individual.

Outcome measures

We examined three outcomes based on survey questions in the NSDUH: prescription opioid use, misuse, and use disorder, sources of prescription opioids for misuse, and use of other substances and drugs of abuse. NSDUH specifically identifies prescription opioids by presenting a list of prescription opioids and pictures of prescription opioid pills to respondents, and asks about past month, year or lifetime use of these opioids. For participants providing a positive response, follow-up questions determine classification into one of three groups: use without misuse, misuse without use disorder, or use disorder. Prescription opioid misuse is defined as “use in any way that a doctor did not direct you to use them” [ 27 ]. Specific examples constituting misuse are provided, including use without a prescription and using prescription opioids “more than you intended to” [ 28 ]. Opioid use disorder is classified as “recurrent use which causes clinically significant impairment, including health problems, disability, and failure to meet major responsibilities at work, school, or home,” based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders , 4th edition (DSM-IV), criteria for substance use disorder [ 29 , 30 ].

For respondents reporting misuse of prescription opioids in the past year, NSDUH collects data on where the medications were obtained. Respondents are asked to select as many responses as apply from the following options: (a) obtained from one doctor, (b) obtained from more than one doctor, (c) stole from doctor office, clinic, hospital, or pharmacy, (d) obtained from friend or relative for free, (e) bought from friend or relative, (f) stole from friend or relative, (g) bought from drug dealer or stranger, and (h) got some other way.

The NSDUH also asks respondents about additional substance use and drug abuse. For our population, we examined responses to questions on tobacco, alcohol, cocaine, cannabis, heroin, inhalant, and hallucinogen use. Questions address use within the past month, past year, and lifetime. We combined use with and without use disorder for these substances and drugs.

Sociodemographic characteristics collected in the NSDUH include sex, race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, and Asian/Native American), health insurance (private, Medicare, Medicaid, uninsured, or other), marital status, educational attainment, and past-year family income (<$20,000, $20,000–$49,999, $50,000–$74,999, and ≥$75,000).

The reliability of the NSDUH questionnaire related to substance use and misuse has been previously assessed, with measures showing good reproducibility over time [ 31 , 32 ]. Missing values in NSDUH are imputed by SAMHSA prior to release of the dataset using a predictive mean neighborhood (PMN) and a modified PMN as detailed in the NSDUH codebook [ 26 ]. PMN is a method of imputing missing or ambiguous values that is similar to predictive mean matching and has been used in the survey since 1999 [ 33 ]. The median percentage of values imputed for the initial demographic variables was 3.5% in 2015 and 3.7% in 2016. For the prescription drug variables, the median percentage of imputed values was 1.0% in 2015 and 0.65% in 2016 [ 26 , 34 ].

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using the person-level sample weight, which is the product of the corresponding sampling fractions at each stage in the sample design, and allows extrapolation to national population estimates. The sampling weights are adjusted using the generalized exponential model [ 35 ], which adjusts for survey nonresponse, post-stratification, and extreme weights, yielding an unbiased national estimate of occurrences and characteristics. When generating population estimates from survey data, we accounted for the survey design by specifying the primary sampling units and the degrees of freedom provided by NSDUH to ensure accurate estimates [ 34 ]. All analyses were performed in STATA Version 15 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) using the suite of estimation commands for survey data ( svyset and svy ).

We calculated descriptive statistics for adolescents and young adults with past-year use of prescription opioids, both overall and stratified by misuse and use disorder. We also assessed the sources of prescription opioids, overall and stratified by misuse and use disorder, and calculated the prevalence of additional use of other substances and drugs of abuse, stratified by prescription opioid use and misuse. Results were calculated and reported with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and P values for comparisons were calculated using chi-squared test. The study conforms to the STROBE guideline ( S1 STROBE Checklist ).

The NSDUH included 27,857 adolescent and 28,213 young adult respondents during the survey years 2015 to 2016, corresponding to an estimated 119.3 million individuals in the extrapolated national population (49.8 million adolescents and 69.5 million young adults). Overall, 27.5% of these respondents, corresponding to an estimated 32.8 million individuals, reported using a prescription opioid in the previous year, including 21.0% (95% CI 20.4–21.6) of adolescents and 32.2% (95% CI 31.4–33.0) of young adults ( Table 1 ).

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002922.t001

Opioid misuse or use disorder in the past year was reported by 6.1% (95% CI 5.8–6.4) of respondents, corresponding to an estimated 1.9 million adolescents (3.8%; 95% CI 3.5–4.0) and 5.4 million young adults (7.8%; 95% CI 7.3–8.2; P < 0.001). Prevalence of opioid misuse without use disorder was higher in young adults compared with adolescents (21.1% [95% CI 19.8–22.3] versus 15.2% [95% CI 13.9–16.5], respectively; P < 0.001), with similar prevalence of opioid use disorder in the two groups. Considering both age groups together, female respondents were more likely to have had any prescription opioid use compared with males (30.3% [95% CI 29.7–30.9] versus 24.8% [95% CI 24.2–25.4], P < 0.001), but male respondents were more likely to have opioid misuse without use disorder compared with females (23.2% [95% CI 21.6–24.8] versus 15.8% [95% CI 14.7–16.9], respectively; P < 0.001). Non-Hispanic white and black respondents reported higher prevalence of past-year opioid use compared with Hispanic respondents ( P < 0.001), but prevalence of misuse without and with use disorder were similar between groups. Insurance status was not a significant determinant of opioid use, but uninsured respondents were more likely to report opioid misuse without use disorder compared with those with Medicaid.

Among those with prescription opioid misuse, 25.4% (95% CI 23.5–27.2) obtained them from the healthcare system, 55.7% (95% CI 53.7–57.6) from friends or relatives, and 18.9% (95% CI 17.4–20.5) through other means ( Table 2 ). Adolescents with opioid misuse obtained opioids most commonly for free from a friend or relative (33.5%; 95% CI 28.7–38.3) or by prescription from a single doctor (19.2%; 95% CI 16.4–22.1). Far fewer obtained them by stealing from a healthcare facility (1.7%; 95% CI 0.5–2.8), through prescriptions from multiple doctors (2.2%; 95% CI 1.3–3.2), or by buying them from a drug dealer or stranger (6.5%; 95% CI 4.4–8.6). Sources of opioids for young adults with opioid misuse were similar to adolescents, with free procurement from friends or relatives (41.4%; 95% CI 38.8–44.1) and prescription from a single doctor (24.0%; 95% CI 22.1–25.9) the most common sources.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002922.t002

Additional substance use and drug abuse associated with prescription opioid use is shown in Table 3 . Among adolescents and young adults with prescription opioid use without misuse, 50.5% (95% CI 49.2–51.7) had previously used tobacco, 70.5% (95% CI 69.3–71.7) had used alcohol, and 43.9% (95% CI 42.7–45.1) had used marijuana. These prevalence rates were significantly higher for respondents with opioid misuse, with 78.4% (95% CI 76.7–80.1; P < 0.001) reporting use of tobacco, 90.1% (95% CI 89.0–91.3; P < 0.001) use of alcohol, and 80.7% (95% CI 79.2–82.2; P < 0.001) use of marijuana. For cocaine, heroin, hallucinogen, and inhalant use, differences in prevalence of use between those with opioid use without misuse and those with opioid misuse were even more pronounced. Prevalence of cocaine use increased greater than 4-fold from 7.9% (95% CI 7.1–8.7) to 35.5% (95% CI 33.1–38.0; P < 0.001) for respondents with opioid use without misuse compared with those with opioid misuse. Similarly, the prevalence in these populations increased from 0.9% (95% CI 0.6–1.1) to 8.7% (95% CI 7.1–10.2; P < 0.001) for heroin use, 13.1% (95% CI 12.3–13.9) to 49.4% (95% CI 46.9–51.8; P < 0.001) for hallucinogen use, and 12.1% (95% CI 11.3–12.8) to 30.4% (95% CI 28.1–32.8; P < 0.001) for inhalant use.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002922.t003

Among adolescents and young adults with opioid misuse, prevalence of additional substance use was significantly higher among young adults for all substances except inhalant use ( Table 4 ). These differences were seen both for past month use and for any prior use of substances. Among adolescents, past month use of tobacco, alcohol, and cannabis was 31.2% (95% CI 28.4–34.1), 36.7% (95% CI 32.9–40.5), and 35.3% (95% CI 32.5–38.0), respectively. These prevalence rates increased to 63.9% (95% CI 61.3–66.5; P < 0.001), 77.4% (95% CI 75.3–79.5; P < 0.001), and 55.0 (95% CI 52.4–57.5; P < 0.001), respectively, among young adults. For cocaine and hallucinogens, lifetime prevalence of using the substance more than doubled between adolescents (11.5% [95% CI 9.3–13.7] and 25.4% [95% CI 22.2–28.6], respectively) and young adults (43.9% [95% CI 40.8–47.0], P < 0.001; and 57.7% [95% CI, 54.7–60.7], P < 0.001, respectively) with opioid misuse.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002922.t004

In this national sample of adolescents and young adults, 27.5% reported using a prescription opioid in the past year, with 3.8% of adolescents and 7.8% of young adults engaged in opioid misuse or having a use disorder. Respondents stated that opioids were obtained most frequently from friends or relatives or from a single prescriber, and much less often through drug dealers or from multiple prescribers. Adolescents and young adults with any type of opioid misuse were significantly more likely to use additional substances and drugs of abuse, with a third or more reporting prior use of cocaine, hallucinogens, and inhalants and half or more reporting past month use of tobacco, alcohol, or cannabis. Overall, young adults engaging in opioid misuse have higher rates of additional substance use and drug abuse compared with adolescents.

These findings are consistent with prior research indicating that the opioid epidemic is taking a significant toll on adolescents and young adults. In one large longitudinal study of youths 13 to 25 years of age, new diagnoses of opioid use disorder increased 6-fold between 2001 and 2014 [ 14 ]. Exposures to opioids have also been accompanied by rising rates of opioid poisonings and overdoses among adolescents and young adults. For adolescents 15 to 19 years of age, the annual rate of hospitalizations for opioid poisonings has increased by greater than 170%, while opioid-related deaths have increased by roughly 250% since the late 1990s [ 5 , 15 ]. Overall, among adolescents and young adults, overdose deaths reached an all-time high of 12.6 per 100,000 in 2017, with the majority of these overdoses linked to opioids [ 36 ].

The risk of progression to opioid use disorder and other substance abuse is well-documented for youths exposed to prescription opioids [ 22 , 37 – 39 ]. High school seniors receiving a first-time medical prescription for an opioid have been shown to have a 33% increased risk of future opioid misuse after high school [ 19 ]. This risk increases for adolescents engaging in nonmedical use of prescription opioids. In one survey study, among adolescents engaging in even occasional (3–9 lifetime uses) nonmedical prescription opioid use, greater than 50% met criteria for a substance use disorder by age 35 [ 38 ]. In addition, prescription opioid use among adolescents and young adults is linked to progression to heroin use. An analysis of NSDUH data from 2004 to 2011 showed that the hazard of heroin initiation was 13 times higher among adolescents and young adults 12 to 21 years of age with a history of nonmedical prescription opioid use compared with those without such prior use [ 40 ]. Overall, 76% of respondents who reported a history of heroin use had previously engaged in nonmedical use of prescription opioids. This risk of progression from nonmedical prescription opioid use to heroin use appears to be significantly greater for young adults compared with persons 25 years and older [ 41 ].

Sources of prescription opioids have not been well defined among adolescents and young adults misusing these drugs. Adults misusing prescription opioids have been found to obtain opioids both from prescribers and through friends and relatives [ 10 ]. Previous work among middle and high school students indicates that diversion of opioids, defined as selling, trading, giving away, or loaning prescription opioids, plays an important role in opioid misuse, with as many as 22% of students with medical use of prescription opioids approached to divert their opioid medication [ 42 , 43 ]. Our findings confirm these reports and quantify sources of prescription opioids, indicating that nearly half of adolescents and 58% of young adults misusing opioids receive them from friends and relatives. In addition, 22% of adolescents and 25% of young adults obtain opioid medications from prescribers, pointing to another area for targeted intervention for reducing opioid misuse. However, it should be noted that very few respondents received prescriptions from multiple prescribers, indicating that prescription drug monitoring programs—which are designed to monitor opioid prescriptions across providers and settings—alone may be insufficient as a policy approach to reduce opioid misuse in youths.

Adolescents and young adults misusing opioids are at high risk of abusing other substances. In addition to our findings of high prevalence of recent substance abuse, prior studies have demonstrated high prevalence of explicit co-ingestion of drugs with prescription opioids. Among high school seniors, approximately 70% report co-ingesting another drug while engaging in prescription opioid misuse, with greater than half reporting concurrent use of marijuana or alcohol, and 10% concurrent use of cocaine, tranquilizers, or amphetamines [ 44 ]. These patterns highlight the importance of screening adolescents and young adults with opioid misuse for use of other substances. In the emergency department setting, screening followed by brief interventions have been shown to be well received and effective at reducing alcohol and marijuana use among adolescents and young adults [ 45 – 47 ]. Providers should consider screening all adolescents and young adults presenting to the emergency department or other healthcare settings with opioid misuse for additional substance use. Healthcare facilities should also have established intervention plans or referral options available to maximize the opportunity to provide substance use treatment to this population.

Our study has several limitations. While the NSDUH had a high response rate of approximately 75% during the years analyzed, we cannot preclude self-selection bias among participants. In addition, despite sophisticated interviewing techniques, we cannot exclude socially desirable reporting among participants. The NSDUH also does not survey homeless people, active military personnel, or people in prison, which might impact findings reported for young adults in the study, especially because high rates of opioid misuse and use disorder have been identified in these populations [ 48 , 49 ]. Because the study does not employ a longitudinal design, we were unable to evaluate patterns of opioid use or progression to other substance use and drug abuse over time for individuals.

Our findings suggest that the prevalence of prescription opioid use among adolescents and young adults in the US is high despite known risks for future opioid and other drug use disorders. Prevention and treatment efforts should take into account that greater than half of adolescents and young adults misusing prescription opioids obtain these drugs from friends and relatives. Both adolescents and young adults misusing opioids demonstrate high prevalence of additional substance use and drug abuse, underscoring the importance of drug and alcohol screening programs in this population.

Supporting information

S1 strobe checklist. strobe statement—a checklist of items that should be included in reports of observational studies..

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002922.s001

- View Article

- PubMed/NCBI

- Google Scholar

- 2. National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). Overdose Death Rates [cited 2018 Aug 13]. Available from: https://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates

- 3. Curtin SC, Tejada-Vera B, Warner M. Drug Overdose Deaths Among Adolescents Aged 15–19 in the United States: 1999–2015 Key findings. 1999 [cited 2018 Sep 4]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db282.pdf .

- 8. Curtin SC, Heron M, Miniño AM, Warner M. National Vital Statistics Reports Volume 67, Number 4 June 01, 2018 Deaths: Recent Increases in Injury Mortality Among Children and Adolescents Aged 10–19 Years in the United States: 1999–2016. 2018;67 [cited 2018 Nov 10]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr67/nvsr67_04.pdf .

- 17. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: National Center for Health Statistics. Youth Risk Behavior Survey Questionnaire. 2015 [cited 2018 Aug 31]. Available from: www.cdc.gov/yrbs .

- 18. Johnston LD, Miech RA, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, Patrick ME. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use: 1975–2017: Overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. 2018 [cited 2018 Sep 1]. Available from: http://www.monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/mtf-overview2017.pdf .

- 26. Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Methodological summary and definitions. 2017 [cited 2018 Oct 3]. Available from: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-MethodSummDefs-2016/NSDUH-MethodSummDefs-2016.htm#seca .

- 27. Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. Results from the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables, Prevalence Estimates, Standard Errors, P Values, and Sample Sizes [cited 2018 Oct 4]. Available from: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015.pdf .

- 28. Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH): Final Approved CAI Specifications for Programming [cited 2018 Oct 10]. Available from: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUHmrbCAIquex2016v2.pdf .

- 29. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV-TR. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC; 2000.

- 30. Hedden SL, Kennet J, Lipari R, Medley G, Tice P, Copello EA, et al. Behavioral Health Trends in the United States: Results from the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health [cited 2018 Dec 8]. Available from: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-FRR1-2014/NSDUH-FRR1-2014.pdf .

- 31. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Reliability of Key Measures in the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. 2010 [cited 2018 Dec 8]. Available from: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/2k6ReliabilityP/2k6ReliabilityP.pdf .

- 32. Kennet J, Painter D, Hunter SR, Granger RA, Bowman KR. Assessing the reliability of key measures in the National Survey on Drug Use and Health using a test-retest methodology [cited 2018 Nov 3]. Available from: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/7218/49d3fb6340708b3914ebe512b7b6c8caf654.pdf .

- 33. Singh AC, Grau EA, Folsom RE. Predictive Mean Neighborhood Imputation with Application to the Person-Pair Data of the National Household Survey on Drug Abuse [cited 2018 Jan 8]. Available from: http://www.asasrms.org/Proceedings/y2001/Proceed/00460.pdf .

- 34. Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health Methodological Resource Book Section 11: Person-Level Sampling Weight Calibration. 2017 [cited 2018 Nov 5]. Available from: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUHmrbSamplingWgt2015.pdf .

- 35. Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. National Survey on Drug Use and Health. 2015 [cited 2018 Nov 5]. Available from: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-RedesignChanges-2015.pdf .

- 36. Hedegaard H, Miniño AM, Warner M. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999–2017. NCHS Data Brief, 329. 2018 [cited 2018 Jan 5]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db329_tables-508.pdf#3 .

- 41. Muhuri PK, Gfroerer JC, Davies MC. CBHSQ Data Review: Associations of Nonmedical Pain Reliever Use and Initiation of Heroin Use in the United States [cited 2018 Dec 10]. Available from: http://www.samhsa.gov/data/ .

Misuse of Prescription Drugs Research Report

About this resource:.

Source: National Institute on Drug Abuse

The last reviewed date indicates when the evidence for this resource last underwent a comprehensive review.

Workgroups: Older Adults Workgroup , Substance Use Workgroup

This report defines misuse of prescription drugs and describes the extent of prescription drug misuse in the United States. It also provides information about the safety of using prescription drugs in combination with other medicines, describes ways to prevent and treat prescription drug misuse and addiction, and lists resources that provide more information. In addition, the report includes information about prescription drug misuse in specific populations, like adolescents and older adults.

Objectives related to this resource (2)

Suggested citation.

National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2020). Misuse of Prescription Drugs Research Report. Retrieved from https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/research-reports/misuse-prescription-drugs

The Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (ODPHP) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by ODPHP or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

The High Cost of Prescription Drugs in the United States: Origins and Prospects for Reform

Affiliation.

- 1 Program On Regulation, Therapeutics, And Law (PORTAL), Division of Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacoeconomics, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women's Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts.

- PMID: 27552619

- DOI: 10.1001/jama.2016.11237

Importance: The increasing cost of prescription drugs in the United States has become a source of concern for patients, prescribers, payers, and policy makers.

Objectives: To review the origins and effects of high drug prices in the US market and to consider policy options that could contain the cost of prescription drugs.

Evidence: We reviewed the peer-reviewed medical and health policy literature from January 2005 to July 2016 for articles addressing the sources of drug prices in the United States, the justifications and consequences of high prices, and possible solutions.

Findings: Per capita prescription drug spending in the United States exceeds that in all other countries, largely driven by brand-name drug prices that have been increasing in recent years at rates far beyond the consumer price index. In 2013, per capita spending on prescription drugs was $858 compared with an average of $400 for 19 other industrialized nations. In the United States, prescription medications now comprise an estimated 17% of overall personal health care services. The most important factor that allows manufacturers to set high drug prices is market exclusivity, protected by monopoly rights awarded upon Food and Drug Administration approval and by patents. The availability of generic drugs after this exclusivity period is the main means of reducing prices in the United States, but access to them may be delayed by numerous business and legal strategies. The primary counterweight against excessive pricing during market exclusivity is the negotiating power of the payer, which is currently constrained by several factors, including the requirement that most government drug payment plans cover nearly all products. Another key contributor to drug spending is physician prescribing choices when comparable alternatives are available at different costs. Although prices are often justified by the high cost of drug development, there is no evidence of an association between research and development costs and prices; rather, prescription drugs are priced in the United States primarily on the basis of what the market will bear.

Conclusions and relevance: High drug prices are the result of the approach the United States has taken to granting government-protected monopolies to drug manufacturers, combined with coverage requirements imposed on government-funded drug benefits. The most realistic short-term strategies to address high prices include enforcing more stringent requirements for the award and extension of exclusivity rights; enhancing competition by ensuring timely generic drug availability; providing greater opportunities for meaningful price negotiation by governmental payers; generating more evidence about comparative cost-effectiveness of therapeutic alternatives; and more effectively educating patients, prescribers, payers, and policy makers about these choices.

PubMed Disclaimer

- Drug prices are kept high in US by protection and price negotiations, study finds. McCarthy M. McCarthy M. BMJ. 2016 Aug 23;354:i4640. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4640. BMJ. 2016. PMID: 27553038 No abstract available.

- Factors Influencing Prescription Drug Costs in the United States. Arbiser JL. Arbiser JL. JAMA. 2016 Dec 13;316(22):2430-2431. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.17290. JAMA. 2016. PMID: 27959990 No abstract available.

- Factors Influencing Prescription Drug Costs in the United States. Roy V, Hawksbee L, King L. Roy V, et al. JAMA. 2016 Dec 13;316(22):2431. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.17293. JAMA. 2016. PMID: 27959991 No abstract available.

- Cost-related medication underuse: Strategies to improve medication adherence at care transitions. Miranda AC, Serag-Bolos ES, Cooper JB. Miranda AC, et al. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2019 Apr 8;76(8):560-565. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/zxz010. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2019. PMID: 31361859 No abstract available.

Similar articles

- Determinants of Market Exclusivity for Prescription Drugs in the United States. Kesselheim AS, Sinha MS, Avorn J. Kesselheim AS, et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2017 Nov 1;177(11):1658-1664. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.4329. JAMA Intern Med. 2017. PMID: 28892528 Review.

- How to Reduce Prescription Drug Prices: First, Do No Harm. Atlas S. Atlas S. Mo Med. 2020 Jan-Feb;117(1):14-15. Mo Med. 2020. PMID: 32158034 Free PMC article. No abstract available.

- Trends in Prices of Popular Brand-Name Prescription Drugs in the United States. Wineinger NE, Zhang Y, Topol EJ. Wineinger NE, et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2019 May 3;2(5):e194791. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.4791. JAMA Netw Open. 2019. PMID: 31150077 Free PMC article.

- Bib Pharma Monopoly: Why Consumers Keep Landing on "Park Place" and How the Game is Rigged. Levy MS. Levy MS. Am Univ Law Rev. 2016;66(1):247-303. Am Univ Law Rev. 2016. PMID: 28225582

- Points to consider about prescription drug prices: an overview of federal policy and pricing studies. Kucukarslan S, Hakim Z, Sullivan D, Taylor S, Grauer D, Haugtvedt C, Zgarrick D. Kucukarslan S, et al. Clin Ther. 1993 Jul-Aug;15(4):726-38. Clin Ther. 1993. PMID: 8221823 Review.

- Patent Portfolios Protecting 10 Top-Selling Prescription Drugs. Horrow C, Gabriele SME, Tu SS, Sarpatwari A, Kesselheim AS. Horrow C, et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2024 Jul 1;184(7):810-817. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2024.0836. JAMA Intern Med. 2024. PMID: 38739386

- The Economic Impact of Atopic Dermatitis. Adamson AS. Adamson AS. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2024;1447:91-104. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-54513-9_9. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2024. PMID: 38724787 Review.

- Lessons From Insulin: Policy Prescriptions for Affordable Diabetes and Obesity Medications. Nagel KE, Ramachandran R, Lipska KJ. Nagel KE, et al. Diabetes Care. 2024 Aug 1;47(8):1246-1256. doi: 10.2337/dci23-0042. Diabetes Care. 2024. PMID: 38536964 Review.

- Insurance-based Disparities in Outcomes and Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Utilization for Hospitalized COVID-19 Patients. Glance LG, Joynt Maddox KE, Mazzeffi M, Shippey E, Wood KL, Yoko Furuya E, Stone PW, Shang J, Wu IY, Gosev I, Lustik SJ, Lander HL, Wyrobek JA, Laserna A, Dick AW. Glance LG, et al. Anesthesiology. 2024 Jul 1;141(1):116-130. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000004985. Anesthesiology. 2024. PMID: 38526387

- Delayed treatment initiation of oral anticoagulants among Medicare patients with atrial fibrillation. Luo X, Chaves J, Dhamane AD, Dai F, Latremouille-Viau D, Wang A. Luo X, et al. Am Heart J Plus. 2024 Feb 2;39:100369. doi: 10.1016/j.ahjo.2024.100369. eCollection 2024 Mar. Am Heart J Plus. 2024. PMID: 38510996 Free PMC article.

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

Related information

- Cited in Books

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources.

- Ovid Technologies, Inc.

- Silverchair Information Systems

Other Literature Sources

- scite Smart Citations

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

- Open access

- Published: 03 March 2022

A systematic umbrella review of the association of prescription drug insurance and cost-sharing with drug use, health services use, and health

- G. Emmanuel Guindon 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Tooba Fatima 1 ,

- Sophiya Garasia 1 , 2 &

- Kimia Khoee 1

BMC Health Services Research volume 22 , Article number: 297 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

3145 Accesses

10 Citations

18 Altmetric

Metrics details

Increasing spending and use of prescription drugs pose an important challenge to governments that seek to expand health insurance coverage to improve population health while controlling public expenditures. Patient cost-sharing such as deductibles and coinsurance is widely used with aim to control healthcare expenditures without adversely affecting health.

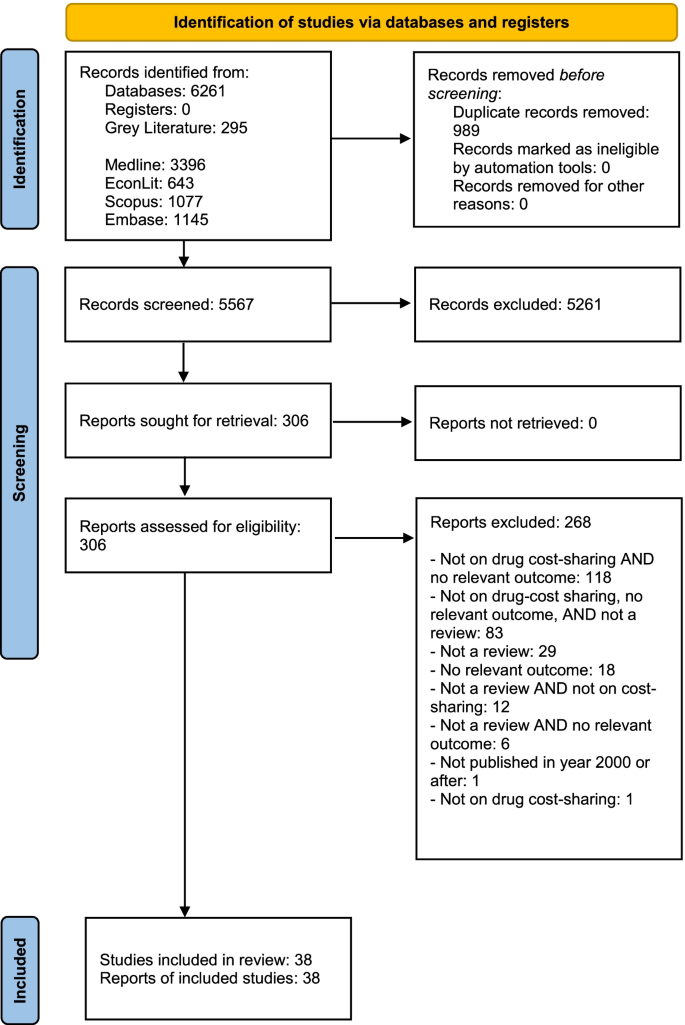

We conducted a systematic umbrella review with a quality assessment of included studies to examine the association of prescription drug insurance and cost-sharing with drug use, health services use, and health. We searched five electronic bibliographic databases, hand-searched eight specialty journals and two working paper repositories, and examined references of relevant reviews. At least two reviewers independently screened the articles, extracted the characteristics, methods, and main results, and assessed the quality of each included study.

We identified 38 reviews. We found consistent evidence that having drug insurance and lower cost-sharing among the insured were associated with increased drug use while the lack or loss of drug insurance and higher drug cost-sharing were associated with decreased drug use. We also found consistent evidence that the poor, the chronically ill, seniors and children were similarly responsive to changes in insurance and cost-sharing. We found that drug insurance and lower drug cost-sharing were associated with lower healthcare services utilization including emergency room visits, hospitalizations, and outpatient visits. We did not find consistent evidence of an association between drug insurance or cost-sharing and health. Lastly, we did not find any evidence that the association between drug insurance or cost-sharing and drug use, health services use or health differed by socioeconomic status, health status, age or sex.

Conclusions

Given that the poor or near-poor often report substantially lower drug insurance coverage, universal pharmacare would likely increase drug use among lower-income populations relative to higher-income populations. On net, it is probable that health services use could decrease with universal pharmacare among those who gain drug insurance. Such cross-price effects of extending drug coverage should be included in costing simulations.

Peer Review reports

As the US strives to reduce its uninsurance rate, it faces an intensifying challenge of increasing out-of-pocket costs in employer-sponsored health insurance [ 1 , 2 ]. All the while Canada is debating how best to provide drug insurance to all its residents [ 3 ]. Canada is often cited as the only high-income country with universal health insurance coverage lacking universal coverage for prescription drugs [ 4 ]. Increasing spending and use of prescription drugs pose an important challenge to governments that seek to expand health insurance coverage to improve population health while controlling public expenditures. Patient cost-sharing such as deductibles and coinsurance is widely used with aim to control healthcare expenditures without adversely affecting health [ 5 ].

Since the seminal RAND Health Insurance Experiment [ 6 ], numerous studies have examined, at various times and across diverse settings, the impact of health insurance generally, and drug insurance in particular, on utilization and health outcomes. For example, in the US, the introduction of Medicare Part D in 2003 and the Affordable Care Act in 2010 have generated a wealth of new research [ 7 , 8 ]. Likewise in Canada, the prospect of universal pharmacare and important changes to provincial drug programs such as the 1997 public/private prescription drug program that covered all Québec residents and British Columbia’s adoption of income-based Pharmacare in 2003 in place of an age-based drug benefits program have resulted in an abundance of new analyses [ 3 , 9 , 10 ]. Countless reviews have examined the impact of prescription drug insurance and drug cost-sharing on an array of outcomes such as drug use, health services use, and health, in varied settings and among heterogenous populations. To our knowledge, there has not been an attempt to assess the quality and synthesize evidence from existing reviews. In addition to identifying the strength/credibility of combined associations from reviews to present an objective and comprehensive synthesis of the evidence, such a review of reviews can identify knowledge gaps in the literature, provide useful guidance for future reviews, and have greater implications for policy and practice.

We conducted a systematic umbrella review in order to provide a closer examination of what policy introductions of prescription drug coverage (with and without cost-sharing) would mean for both individuals and governments financing this coverage. We examined reviews that studied the association between having prescription drug coverage (primary and supplementary), as well as varying types and levels of cost-sharing, and:

the utilization of prescription drugs (i.e., own-price effects on drug use);

the utilization of healthcare services (i.e., cross-price effects on the use of health services such as physician, emergency department, and inpatient services);

health outcomes (i.e., own-price effects on health outcomes);

We also examined the degree to which the associations identified in 1–3 above differed across levels of socioeconomic status (SES, e.g., income, education), populations of differing health status such as the chronically ill, age, and sex.

A review protocol was prepared in advance and registered with PROSPERO (CRD42017052018). We searched five electronic bibliographic databases: MEDLINE, Embase, Scopus, EconLit, and Health Systems Evidence. Grey literature was searched via the New York Academy of Medicine Grey Literature Report, Open Grey, Google, and Google Scholar. Eight specialty journals (BMC Health Services Research, Health Affairs, Healthcare Policy, Health Economics, Journal of Health Economics, Health Economics, Policy and Law, Health Services Research, and Medical Care Research and Review) and two working paper repositories (RePEc, Research Papers in Economics and the National Bureau of Economic Research working paper series) were ‘hand-searched.’ We examined references of included reviews and of reviews that cited key studies using Web of Science and Google Scholar. The database search was last updated on September 15, 2020. At least two reviewers, using distillerSR, screened titles and abstracts of citations to determine relevance, then full text if relevance was unclear.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Types of studies: all reviews (e.g., narrative, rapid, scoping, systematic, meta-analysis, meta-regression). Types of interventions: (1) insurance: all studies that examined the expansion of prescription drug insurance, irrespective of the insurance provider (e.g., government, employers, professional associations) and studies that examined partial or full-delisting of prescription drugs from insurance coverage; (2) cost-sharing: all studies that examined any form of direct patient payment for prescription drugs including, but not limited to, fixed copayment, coinsurance, ceilings, and caps. Types of outcomes: all reviews that included as an outcome any of drug utilization, health services utilization, or health outcomes. Time period: all reviews published since January 2000. Languages: we included only studies written in English and French. We excluded reviews that focused solely on low- and middle-income countries.

Quality assessment and data extraction

We used the Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) measurement tool as a methodological guide [ 11 ]. Although AMSTAR’s focus is primarily on the reporting quality of reviews, we paid particular attention to the quality assessment conducted in each review. At least two reviewers independently extracted detailed study characteristics for each included review using a standardized form, including all AMSTAR 2 items (see Additional file 1 ). The following study characteristics were extracted, where possible: citation, type of review, population investigated, research question, outcomes studied, whether there was an ‘a priori design’ and duplicate study selection and data extraction, the comprehensiveness of the search including if grey literature was searched, year/month of last search, whether the keywords/search strategy were reported, total number of studies included, total number of studies included that focused on drug insurance and/or cost-sharing, whether a list of included and excluded studies were provided, whether the characteristics of the included studies were provided, whether the scientific quality of the included studies was assessed, documented, and used appropriately in formulating conclusions, whether the methods used to combine the findings of studies were appropriate, whether the likelihood of publication bias was assessed, whether funding and competing of interests were clearly reported, key results for each of drug use, healthcare services utilization, and health, and reviews’ conclusion (as stated by the authors). In assessing the quality of the included studies, we paid particular attention to the following components: ‘a priori’ design; duplicate study selection and data extraction; systematic search strategy; presentation of characteristics of included studies and list of excluded studies and reasons for exclusion; quality assessment of included studies; and the generalizability of the findings. We did not compute total scores as empirical evidence does not support their use [ 12 , 13 , 14 ]. We created summary tables, organized by outcome and subgroup, using our completed standardized forms. For each study, we highlighted the direction and magnitude of the associations. In our descriptive table, we present the study citations, research question, outcomes studied, study selection and extraction process, quality assessment, and limitations/risk of bias. Lastly, given the current policy debate surrounding universal pharmacare in Canada, we also reported the total number of Canadian studies included that focused on drug insurance and/or cost-sharing [ 3 ].