REVIEW article

Poverty reduction of sustainable development goals in the 21st century: a bibliometric analysis.

- Institute of Blue and Green Development, Shandong University, Weihai, China

No Poverty is the top priority among 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The research perspectives, methods, and subject integration of studies on poverty reduction have been greatly developed with the advance of practice in the 21st century. This paper analyses 2,459 papers on poverty reduction since 2000 using VOSviewer software and R language. Our conclusions show that (1) the 21st century has seen a sharp increase in publications of poverty reduction, especially the period from 2015 to date. (2) The divergence in research quantity and quality between China and Kenya is great. (3) Economic studies focus on inequality and growth, while environmental studies focus on protection and management mechanisms. (4) International cooperation is usually related to geographical location and conducted by developed countries with developing countries together. (5) Research on poverty reduction in different regions has specific sub-themes. Our findings provide an overview of the state of the research and suggest that there is a need to strengthen the integration of disciplines and pay attention to the contribution of marginal disciplines to poverty reduction research in the future.

Introduction

Global sustainable development is the common target of human society. “No Poverty” and “Zero Hunger” are two primary goals of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (SDGs) , along with important premises in the completion of the goals of “Decent Work and Economic Growth Industry” and “Innovation and Infrastructure.” China has made great efforts in meeting its No Poverty targets. To achieve the goal of eliminating extreme poverty in the rural areas by the end of2020 1 , China has been carrying out a basic strategy of targeted approach named Jingzhunfupin 2 , which refers to implementing accurate poverty identification, accurate support, accurate management and tracking. By 2021, China accomplished its poverty alleviation target for the new era on schedule and achieved a significant victory 3 .

However, the worldwide challenges are still arduous. On the one hand, the recent global poverty eradication process has been further hindered by the COVID-19 pandemic. The World Bank shows that global extreme poverty rose in 2020 for the first time in over 20 years, with the total expected to rise to about 150 million by the end of 2021 4 . People “return to poverty” are emerging around the world. On the other hand, people who got out of income poverty may still be trapped in deprivations in health or education. About 1.3 billion people (22%) still live in multidimensional poverty among 107 developing countries, according to the Global Multidimensional Poverty Index report released by the United Nations 5 . Meanwhile, the issue of inequality became more prominent, reflected by the number of people who are in relative poverty 6 .

In line with the dynamic poverty realities, the focusing of poverty research moved forward as well. Research frameworks have evolved from single dimension poverty to multidimensional poverty ( Bourguignon et al., 2019 ) and from income poverty to capacity poverty ( Zhou et al., 2021 ). Research perspectives concentrate on the macroscopic view, but have now turned to microscopic individual behavior analysis. Cross-integration of sociology, psychology, public management, and other disciplines also helps to expand and deepen the research ( Addison et al., 2008 ). Some cutting-edge researchers are making effort to shed light on the relationships between “No Poverty” and other SDGs. For example, Hubacek et al. (2017) verified the coherence of climate targets and achieving poverty eradication from a global perspective 7 . Li et al. (2021) discussed the impacts and synergies of achieving different poverty eradication goals on air pollutants in China. These novel papers give us insightful inspiration on combining poverty reduction with the resource or environmental problem including aspects like energy inequity, carbon emission. Hence, summarizing the research on different poverty realities and academic backgrounds should provide theoretical and empirical guidance for speeding up the elimination of poverty in the world ( Chen and Ravallion, 2013 ).

Previous review literature on poverty reduction all directed certain sub-themes. For example, Chamhuri et al. (2012) , Kwan et al. (2018) , Mahembe et al. (2019a) reviewed urban poverty, foreign aid, microfinance, and other topics, identifying the objects, causes, policies, and mechanisms of poverty and poverty reduction. Another feature of the review literature is that scholars often synthesize the articles and map the knowledge network manually, which constrains the amount of literature to be analyzed, leading to an inadequate understanding of poverty research. Manually literature review on specific fields of poverty reduction results in a research gap. Analysis delineating the general academic knowledge of poverty reduction is somewhat limited despite the abundance of research. Yet, following the trend toward scientific specialization and interdisciplinary viewpoints, the core and the periphery research fields and their connections have not been clearly described. Different studies are in a certain degree of segmentation because scholars have separately conducted studies based on their countries’ unique poverty background or their subdivision direction. Possibly, lacking communication and interaction will affect the overall development of poverty reduction research especially in the context of globalization. Less than 10 years are left to accomplish the UN sustainable development goals by 2030. It is urgent to view the previous literature from a united perspective in this turbulent and uncertain age.

Encouragingly, with advances in analytical technology, bibliometrics has become increasingly popular for developing representative summaries of the leading results ( Merediz-Solà and Bariviera, 2019 ). It has been widely applied in a variety of fields. In the domain of poverty study, Amarante et al. (2019) adopted the bibliometric method and reviewed thousands of papers on poverty and inequality in Latin America. Given above issues, we expand the scope of the literature and conduct a systematic bibliometric analysis to make a preliminary description of the research agenda on poverty reduction.

This paper presents an analysis of publications, keywords, citations, and the networks of co-authors, co-words, and co-citations, displaying the research status of the field, the hot spots, and evolution through time. We use R language and VOSviewer software to process and visualize data. Our contributions may be as follows. Firstly, we used the bibliometric method and reviewed thousands of papers together, helping keep pace with research advances in poverty alleviation with the rapid growth in the literature. Secondly, we clarified the core and periphery research areas, and their connections. These may be beneficial to handle the trend toward scientific specialization, as well as fostering communication and cooperation between disciplines, mitigating segmentation between the individual studies. Thirdly, we also provided insightful implications for future research directions. Discipline integration, intergenerational poverty, heterogeneous research are the directions that should be paid attention to.

The structure of this article is as follows. Methodology and Initial Statistics provides the methodology and initial statistics. Bibliometric Analysis and Network Analysis offer the bibliometric analysis and network visualization. The remaining sections offer discussions and conclusions.

Methodology and Initial Statistics

Bibliometrics, a library and information science, was first proposed by intelligence scientist Pritchard in 1969 ( Pritchard, 1969 ). It exploits information about the literature such as authors, keywords, citations, and institutions in the publication database. Bibliometric analyses can systematically and quantitatively analyze a large number of documents simultaneously. They can highlight research hotspots and detects research trends by exploring the time, source, and regional distribution of literature. Thus, bibliometric analyses have been widely used to help new researchers in a discipline quickly understand the extent of a topic ( Merediz-Solà and Bariviera, 2019 ).

Research tools such as Bibexcel, Histcite, Citespace, and Gephi have been created for bibliometric analysis. In this paper, R language and VOSviewer software are adopted. R language provides a convenient bibliometric analysis package for Web of Science, Scopus, and PubMed databases, by which mathematical statistics were performed on authors, journals, countries, and keywords. VOSviewer software provides a convenient tool for co-occurrence network visualization, helping map the knowledge structure of a scientific field ( Van Eck and Waltman, 2010 ).

Data Collection

The bibliometric data was selected and downloaded from the Web of Science database ( www.webofknowledge.com ). We choose the WoS Core Collection, which contained SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, and A&HCI papers to focus on high-quality papers. The data was collected on March 19, 2021.

To identify the documents, we used verb phrases and noun phrases with the meaning of poverty reduction, such as “reduce poverty” and “poverty reduction,” as search terms, because there are several different expressions of “poverty reduction.” We also considered the combinations of “no poverty” and SDGs, “zero hungry” and “SDGs.” Because the search engine will pick up articles that have nothing to do with “poverty alleviation” depending on what words are used in the abstract, we employed keyword matching. Meanwhile, to prevent missing essential work that does not require author keywords, we also searched the title. Specifically, a retrieval formula can be written as [AK = (“search term”) OR TI = (“search term”)] in the advanced search box, where AK means author keywords and TI means title. Finally, we restricted the document types to “article” to obtain clear data. Thus, papers containing search phrases in headings or author keywords were marked and were guaranteed to be close to the desired topic.

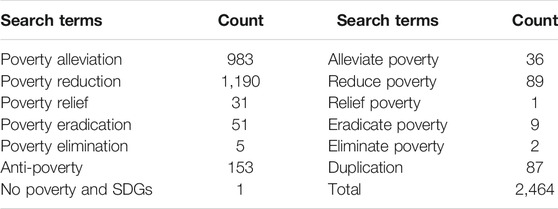

A total of 2,551 studies were obtained, with 2,464 articles retained after removing duplicates. Table 1 presents the results for each search term. The phrasing of “poverty alleviation” and “poverty reduction” are written preferences.

TABLE 1 . Information of data collection.

Descriptive Analysis

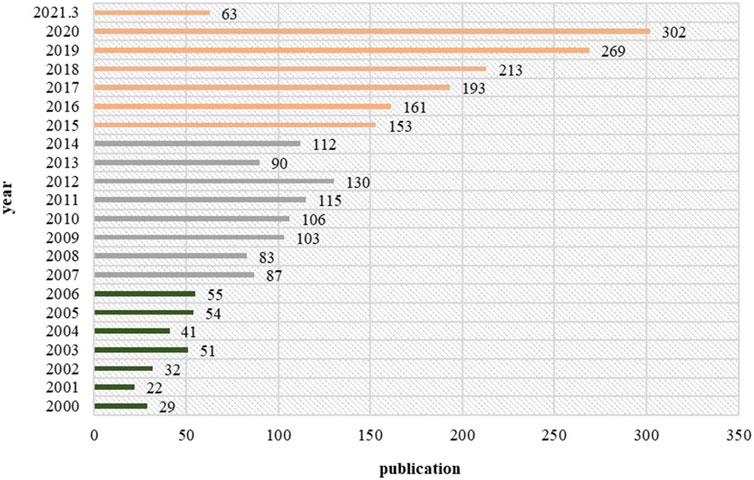

Figure 1 gives details of each year’s publications during the period 2000–2021. The cut-off points of 2006 and 2015 divide the publication trends into three stages. The first period is 2000–2006, with approximately 40 publications per year. The second period is 2007–2014, in which production is between 80 and 130 papers annually. The third period is 2015–2021, with an 18.31% annual growth rate, indicating a growing interest in this field among scholars. Perhaps this is because 2006 was the last year of the first decade for the International Eradication of Poverty, and 2015 is the year that eliminating all forms of poverty worldwide was formally adopted as the first goal in the United Nations Summit on Sustainable Development. Greater access to poverty reduction plan materials and data is a vital reason for the growth in papers as well.

FIGURE 1 . Annual scientific production.

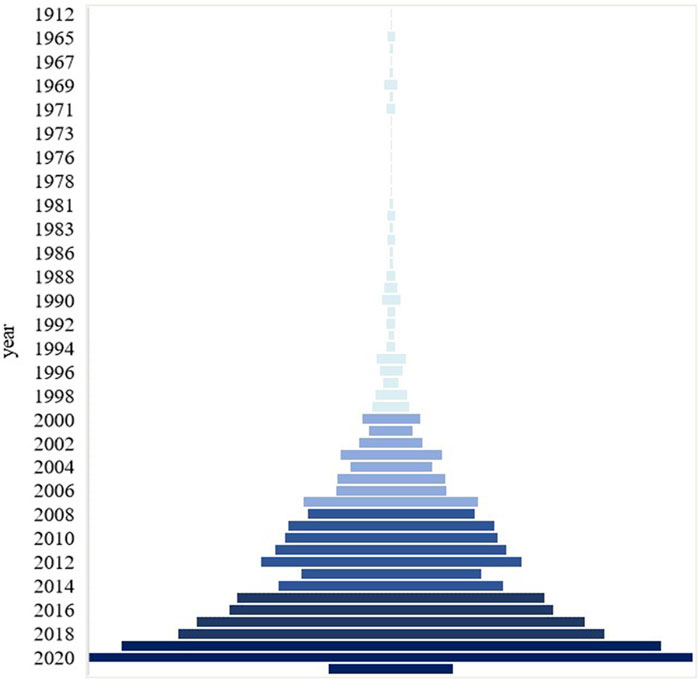

We can notice that the milestone year is 1995 when we examine the time trend with broader horizons ( Figure 2 ). Before 1995, scant literature touches upon the topic of “poverty alleviation.” This confirms that in the time range we check the majority of the development of academic interest in this issue takes place. Thus, the 21st century has become a period of booming research on poverty reduction.

FIGURE 2 . Annual scientific production in a longer period.

Bibliometric Analysis

In this section, we offer the bibliometric analysis including the affiliation statistics, citation analysis and keywords analysis. Author analysis is not included because some authors’ abbreviations have led to statistical errors.

Affiliation Statistics

From 2000 to 2021, a total of 2,459 articles were published in 979 journals, a wide range. Table 2 lists the top ten journals, which together account for 439 (17.86%) of the articles in our data set. Development in Practice and World Development have the most publications, respectively 121 (4.92%) and 107 (4.35%), followed by Sustainability at 44 (1.8%). The top 10 journals mostly involve development or social issues, with some having high impact factors, including Food Policy (4.189) and Journal of Business Ethics (4.141).

TABLE 2 . Top 10 sources of publications.

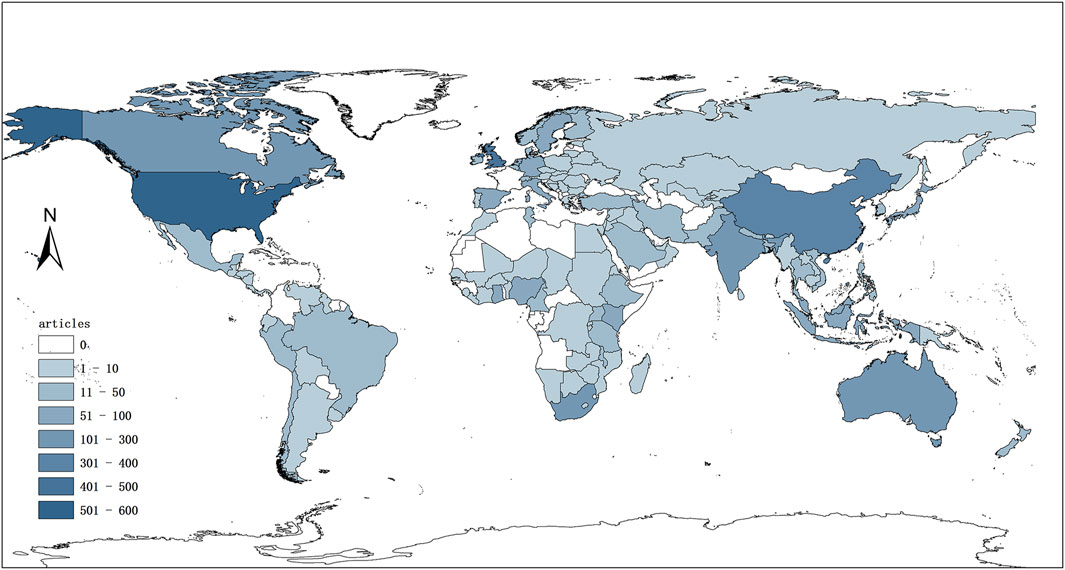

Figure 3 presents the geographic distribution of the published articles on poverty reduction. As indicated in the legend, the white part on the map shows regions with zero published articles recorded in WoS. Darker shades indicate a greater number of articles published in the country or region. The US region is darkest on the map, with 593 articles published, followed by England, with 412 papers, and China, with 348 articles. Ranking fourth is South Africa, perhaps because South Africa is a pilot site for many poverty reduction projects. India, for the same reason, is similarly shaded.

FIGURE 3 . Spatial distribution of publication in all countries. Note: the data of all countries is from Web of Science.

Citation Analysis

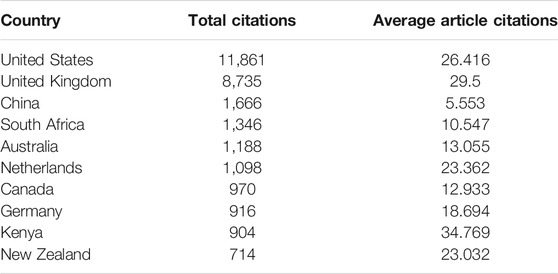

The number of citations evaluates the influence and contribution of individual papers, authors, and nations. The top 10 countries in total citations are displayed in Table 3 . Consistent with the publication distribution, the leader is the United States (11,861), with the United Kingdom (8,735) and China (1,666) following. However, there is a broad gap between China and England in total citations. The average article citation ranks are quite different from the total citation list. Notably, Kenya takes first place based on its average citations per paper, though its total citations rank seventh, showing that Kenya’s poverty reduction practices and research are of great interest to a large number of scholars. By contrast, China’s average article citation is just roughly one-sixth of Kenya’s. The different pattern of the number of Chinese publications and citations shows that the quality of Chinese research must be improved even as it raises its publication quantity.

TABLE 3 . Top ten countries by total citations.

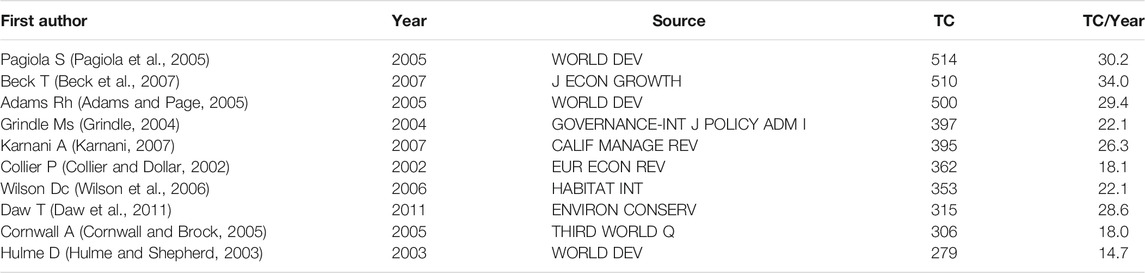

Table 4 lists the top 10 most cited articles with their first author, year, source, total citations, and total citations per year. Highly cited articles can be used as a benchmark for future research, and in some way signal the scientific excellence of each sub-field. For example, Wilson et al. (2006) reminded the importance of informal sector recycling to poverty alleviation. Daw et al. (2011) discussed the poverty alleviation benefits from ecosystem services (ES) with examples in developing countries. Pagiola et al. (2005) found that Payments for Environmental Services (PES) can alleviate poverty, and explored the key factors of this poverty mitigation effect using evidence from Latin America 8 . These three papers combined the environmental ecosystem with poverty alleviation. Beck et al. (2007) , Karnani (2007) explored the relationships between the SME sector and poverty alleviation and the private sector and poverty alleviation, respectively. Grindle (2004) discussed the necessary what, when, and how for good governance of poverty reduction. Cornwall and Brock (2005) took a critical look at how the three terms of “participation,” “empowerment” and “poverty reduction” have come to be used in international development policy. Adams and Page (2005) examined the impact of international migration and remittances on poverty. In the theory domain, Collier and Dollar (2002) derived a poverty-efficient allocation of aid. Hulme and Shepherd (2003) provided meaning for the term chronic poverty. Even from the present point of view, these scholars’ studies remain innovative and significant.

TABLE 4 . Top 10 papers with the highest total citations.

Keywords Analysis

The keywords clarify the main direction of the research and are regarded as a fine indicator for revealing the literature’s content ( Su et al., 2020 ). Two different types of keywords are provided by Web of Science. One is the author keywords, offered by the original authors, and another is the keywords plus, contrived by extracting from the cited reference. The frequency of both types of keywords in 2,459 papers is examined respectively in the whole sample and the sub-sample hereinafter for concentration and coverage.

Whole Sample

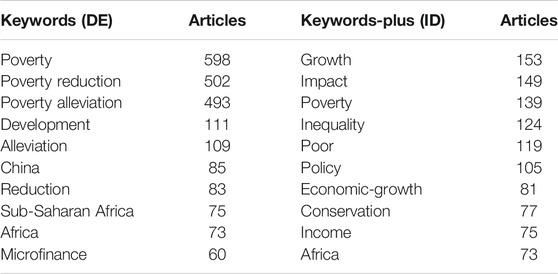

Table 5 lists the Top 10 most frequently used keywords and keyword-plus of total papers. Clearly author keywords are often repetitive, with “poverty,” “poverty reduction,” and “reduction” chosen as keywords for the same paper, but these do not dominate the keywords-plus. Hence, the keywords-plus may be more precise at identifying relevant content. However, we used author keywords for the literature screening.

TABLE 5 . Top 10 author keywords and keywords-plus with the highest frequency.

In addition to the terms “poverty” or “poverty reduction or alleviation,” we note that “China” and “Africa” occur frequently, with “India” and “Bangladesh” following when we expand the list from the Top 10 to Top 20 ( Supplementary Figure S1 ). The appearance of these places coincides with our speculation that the research was often conducted in Africa, East Asia, or South Asia once again, whereas the larger compositions are from developing countries or less developed countries.

The cumulative trend of TOP20 author keywords and keywords-plus is shown in Supplementary Figure S1 . The diagram also gives some information about other concerns bound up with anti-poverty programs, including “microfinance,” “food security,” “livelihoods,” “health,” “Economic-growth” and “income,” as numerous papers are focused on these aspects of poverty reduction.

Further, policy study and impact evaluation may be the core objectives of these papers. Vital evidence can be found in countless documents. Researchers measured the effect of policies or programs from various perspectives. In the study of Jalana and Ravallion (2003) , they indicated that ignoring foregone incomes overstated the benefits of the project when they estimated net gain from the Argentine workfare scheme. Meng (2013) found that the 8–7 plan increased rural income in China’s target counties by about 38% in 1994–2000, but had only a short-term impact 9 . Galiani and McEwan (2013) studied the heterogeneous influences of the Programa de Asignación Familiar (PRAF) program, in which implemented education cash transfer and health cash transfer to people of varying degrees of poverty in Honduran. Maulu et al. (2021) concluded that rural extension programs can provide a sustainable solution to poverty. Some studies also have drawn relatively fresh conclusions or advice on poverty reduction projects. Mahembe et al. (2019a) found that aid disbursed in production sectors, infrastructure and economic development was more effective in reducing poverty through retrospecting empirical studies of official development assistance (ODA) or foreign aid on poverty reduction. Meinzen-Dick et al. (2019) reviewed the literature on women’s land rights (WLR) and poverty reduction, but found no papers that directly investigate the link between WLR and poverty. Huang and Ying (2018) constructed a literature review that included the necessity and the ways of introducing a market mechanism to government poverty alleviation. Mbuyisa and Leonard (2017) demonstrated that information and communication technology (ICT) can be used as a tool for poverty reduction by Small and Medium Enterprises.

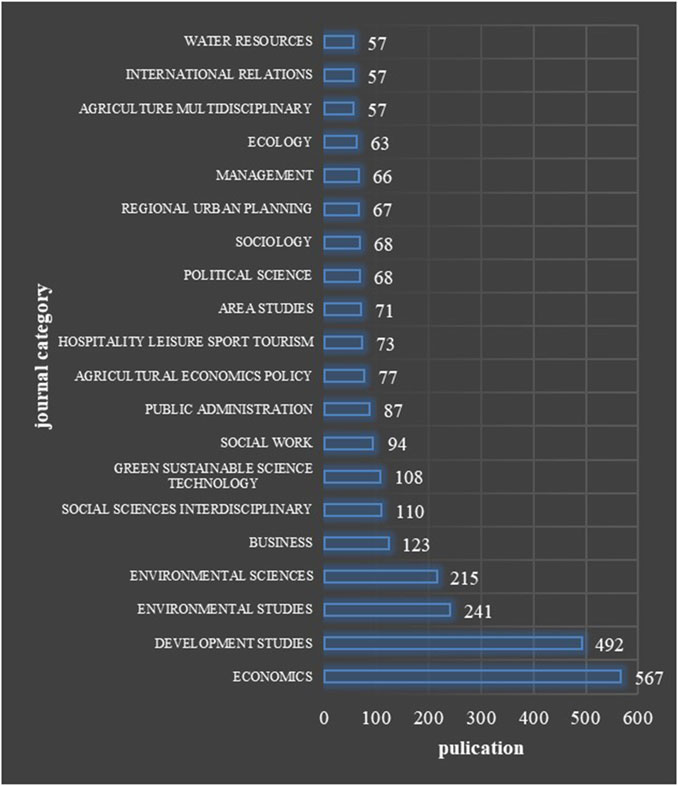

Web of Science provides the publications of each journal category ( Figure 4 ). Economics is the largest type of journal, followed by development studies and environmental studies. Education should be regarded as an important way to address the intergenerational poverty trap. However, we note that journals in education are only a fraction of the total number of journals. Psychology journals are in a similar position, though endogenous drivers of poverty reduction have been increasingly emphasized in recent research. The detailed data can be found in the supplementary documents. To investigate the differences between the subdivisions of the research, we chose economic and environmental journals as sub-samples for further analysis.

FIGURE 4 . Visualization of journal category from the web of science.

As Supplementary Figure S2 shows, the TOP10 author keywords in economic sample are similar to the whole sample. We note that microfinance is a real heated research domain both in economic and whole sample. The poor usually have multiple occupations or self-employment in very small businesses ( Banerjee and Duflo, 2007 ). The poor often have less access to formal credit. Karlan and Zinman (2011) examined a microcredit program in the Philippines and found that microcredit does expand access to informal credit and increase the ability against risk. Banerjee et al. (2015a) reported the results of an assessment of a random microcredit scheme in India, which increased the investment and profits of small-scale enterprises managed by the poor.

Several new keywords enter the TOP20 list in the economic field, including “targeting,” “income distribution,” “productivity,” “employment,” “rural poverty,” “access,” and “program.” “Targeting” is an essential topic in the economic field. It concerns the effectiveness of poverty reduction program and social fairness. Hence, an abundance of literature reviews the definitions of poverty that allow individuals to apply for poverty alleviation programs. Park et al. (2002) , Bibi and Duclos (2007) , Kleven and Kopczuk (2011) , discussed the inclusion error and exclusion error in programs’ targeting and identification under the criterion of poverty lines or specific tangible asset poverty agency indicators (e.g., whether households have color televisions, pumps or flooring, and so forth). In practice, Niehaus et al. (2013) tested the accuracy of different agency indicators to allocate Below Poverty Line (BPL) cards in India and found that using a greater number of poverty indicators led to a deterioration in targeting effectiveness while creating widespread violations in the implementation because less qualified families are more likely to pay bribes to investigators. Bardhan and Mookherjee (2005) explored the targeting effectiveness of decentralization in the implementation of anti-poverty projects. He and Wang (2017) assessed the targeting accuracy of the College Graduate Village Officials (CGVOs) project, a unique human capital redistribution policy in China, on poverty alleviation 10 .

The terms “inequality” and “growth” are first and second in the keywords-plus. This may be because inequality and growth are two of the major components in poverty changes in the economic field, which are stressed in the studies of Datt and Ravallion (1992) , Beck et al. (2007) . The ranking may also imply that the economics of the 21st century is more concerned with human welfare than the pursuit of rapid economic growth. Since a growing number of organizations are trying to build human capital to improve the livelihoods of their clients and further their mission of lifting themselves out of poverty. McKernan (2002) showed that social development programs are important components of microfinance program success. Similarly, Karlan and Valdivia (2006) argued that increasing business training can factually improve business knowledge, practice effectiveness, and revenue. Besides, cash transfers are widely adopted to reduce income inequality and improve education and the health status of poor groups ( Banerjee et al., 2015b ; Sedlmayr et al., 2020 ). Benhassine et al. (2015) noted that the Tayssir Project in Morocco, a cash transfer project, achieved an increasing improvement of school enrolment rate in the treatment group, especially for girls 11 .

We combine the journal types of “Environmental Studies” and “Environmental Sciences” into one unit for analysis ( Supplementary Figure S3 ). In the environmental field, the terms “conservation” and “management” are ranked first and second. This field also involves “ecosystem services,” “climate change,” “biodiversity conservation,” and “deforestation,” with rapid growth in recent years. These themes were discussed by Alix-Garcia et al. (2013) , Alix-Garcia et al. (2015) , Sims and Alix-Garcia (2017) in their investigations of the effect of conditional cash transfers on environmental degradation, the poverty alleviation benefits of the ecosystem service payment project, and comparison of the effects in protected areas and of ecosystem service payment on poverty reduction in Mexico. The differences in economic research in poverty reduction and environmental field show the necessity of strengthening cooperation between disciplines.

Network Analysis

Network relationship is established by the co-occurrence of two types of information. It enables mapping of the knowledge nodes with a joint perspective, instead of viewing scientific ideas in isolation. The data is imported into VOSviewer software after removing duplicates by R package. We then provide the co-authorship analysis, co-citation analysis, and co-keywords analysis.

Co-Authorship Analysis

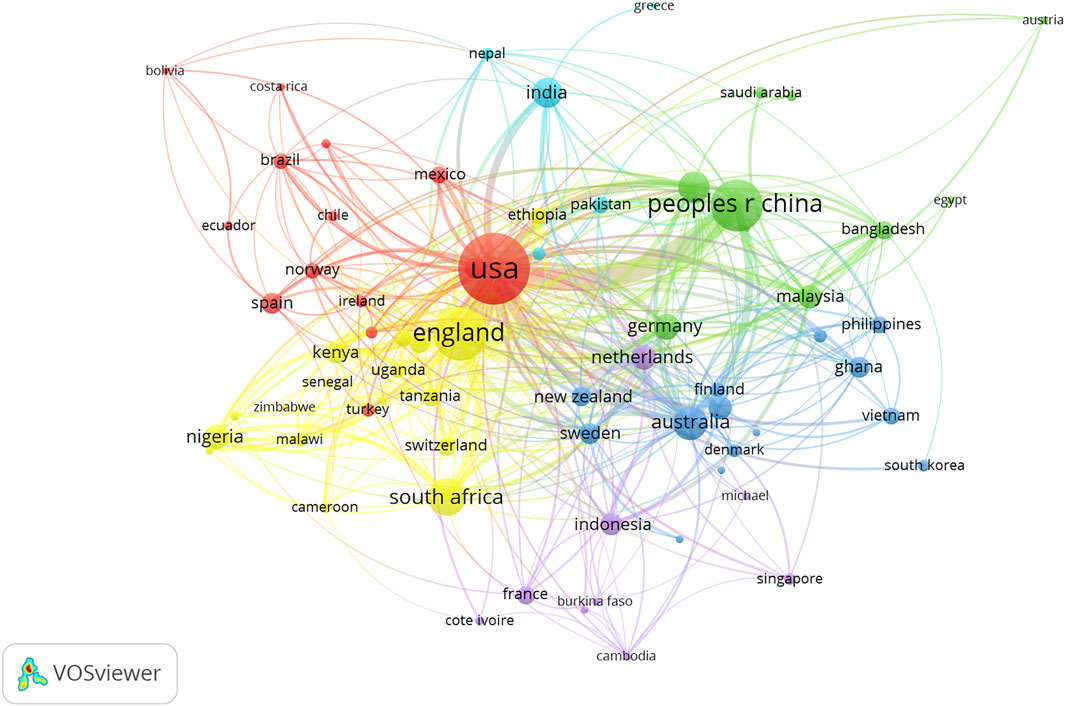

Co-authorship may reflect international cooperation as shown by the country distribution ( Figure 5 ). When the authors of two countries have a cooperative relationship, a line is generated to connect the corresponding countries. The size of nodes reflects the number of countries of origin of the authors. The width of the line represents the cooperative frequency between them, and the different colors mark the partition of the countries.

FIGURE 5 . International networks of co-authorship.

The network includes a total of 1,449 countries, of which 92 meet the threshold of at least five instances of cooperation. The United States, United Kingdom, China, and South Africa have the strongest interlinkage with other countries or regions. Whether countries in each cluster demonstrate international academic cooperation on poverty reduction is sometimes based on geographic location. For example, the red cluster includes the United States, Mexico, Brazil, Chile, and Ecuador. These countries mainly lie in the Americas. The United Kingdom, Kenya, Uganda, and South Africa are in the yellow group, located in Europe and Africa. The green cluster includes China, Malaysia, and Bangladesh, all Asian countries. The distribution of countries on each cluster and the map as a whole show that research on poverty alleviation is usually conducted by developed and developing nations together. This may be due to anti-poverty programs in developed countries usually being subsidized by international non-governmental organizations, as shown by the branch literature devoted to foreign aid and poverty reduction ( Mahembe et al., 2019b ).

Co-Citation Analysis

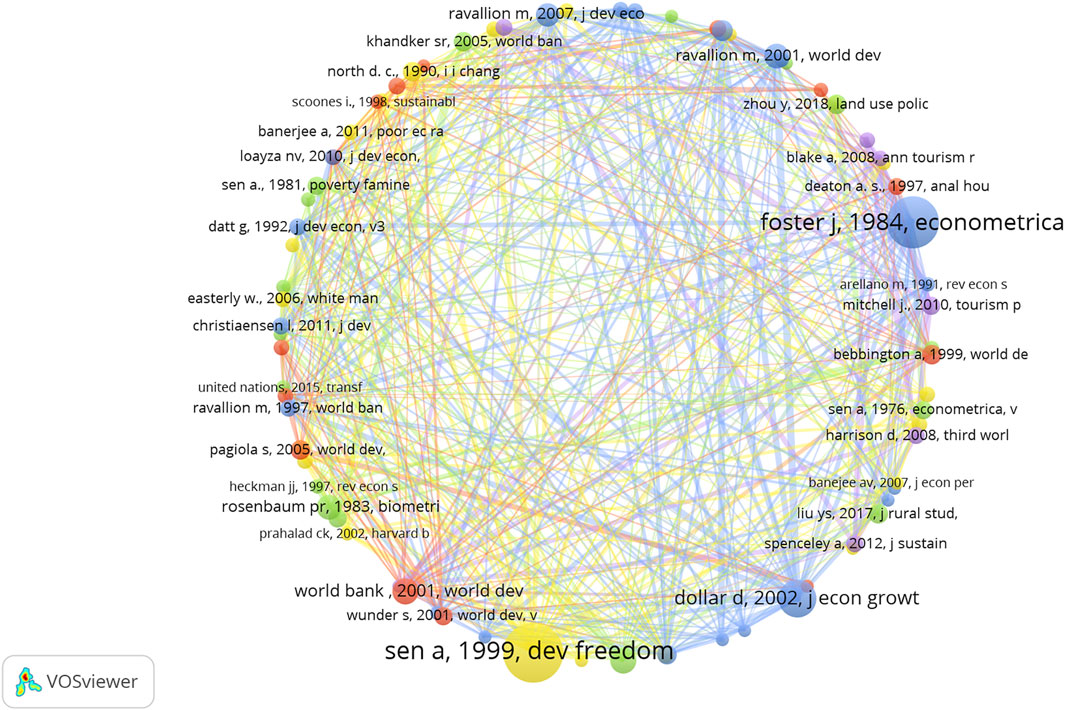

Co-citation analysis can locate the core classical literature efficiently ( Zhang et al., 2020 ). Pioneering studies of co-citation analysis were performed by Small (1973) . When an article cited two other articles, a relationship of co-citation will be established between these two “cited” articles ( González-Alcaide et al., 2016 ). Since co-citation aims at reference, it targets the knowledge base for the past.

Figure 6 displays the co-citation network of the cited references. The functions of the sizes and colors are the same as in Figure 5 . The most cited papers in the co-citation relationship are the studies of Foster et al. (1984) , Sen et al. (1999) , Dollar and Kraay (2002) , which respectively explore poverty measures, globalization and development, and the growth impact for the poor.

FIGURE 6 . Cited reference network of co-citation.

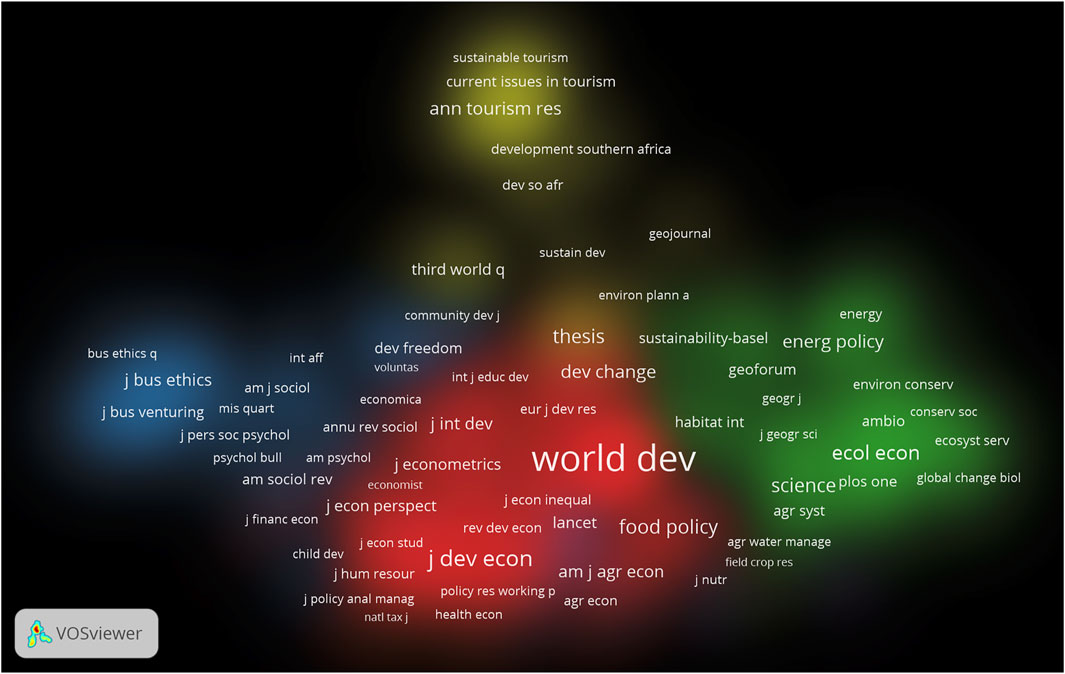

Figure 7 gives the co-citation heat map of sources, based on their density. We set the threshold at 20, and 78 cited sources remained on the map. Different colors signify different clusters of co-citation. The lighter the color, the more frequently the journals are cited. There are four major categories. World development and the Journal of Development Economics have the largest influence on the red cluster, which mainly contains development and economic studies. The second cluster is green and includes the fields of energy, environment, and ecology, with Ecology Economics as its brightest star. The Journal of Business Ethics and Annals of Tourism Research are the most-cited journals in the third and fourth cluster, which represents the fields of business and tourism. Some psychology studies exist in transitional spaces between business studies and economic studies, suggesting a trend of interdisciplinary work. In the past 10 years, we checked manually that psychology and other interdisciplinary research performed well. Many papers were published in Science or Nature. In the research of Mani et al. (2013) , there was a causal relationship between poverty and psychological function. Poverty reduced the cognitive performance of the poor, because poverty consumes spiritual resources, leaving fewer cognitive resources to guide choices and actions. Another psychology-based experiment in Togo showed that personal proactive training increased the profits of poor businesses by 30%, while traditional training influence was not significant ( Campos et al., 2017 ). In the study of Ludwig et al. (2012) , they revealed that the shift from high-poverty to low-poverty communities resulted in significant long-term improvements in physical and mental health and subjective well-being and had a continuing impact on collective efficacy and neighborhood security.

FIGURE 7 . Cited source density network of co-citation.

Co-Words Analysis

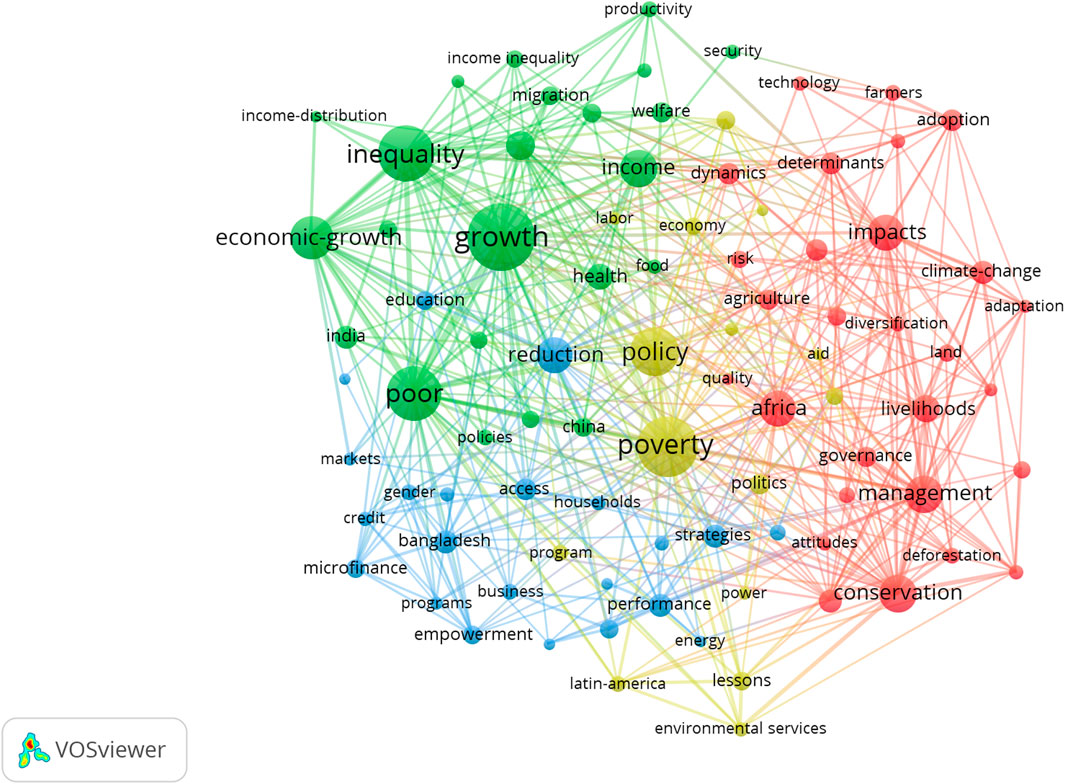

The analysis of co-words was performed after the co-citation analysis. Since it is hard to explain the changes in cluster from year to another in a co-citation map, Callon et al. (1983) proposed co-word analysis to identify and visualize scientific networks and their evolution. Based on our keyword analysis and following the arguments of Zhang et al. (2016) , the knowledge structures of author keywords and keywords plus are similar, but keywords plus can mirror a large proportion of the author keywords when the threshold of the number of instances of a word exceeds 10. The merger of two types of keywords will inflate the total number of words, leaving unique words representing the latest hot spot with little chance to be selected. Therefore, we conduct the co-word analysis using keywords plus to map the structure.

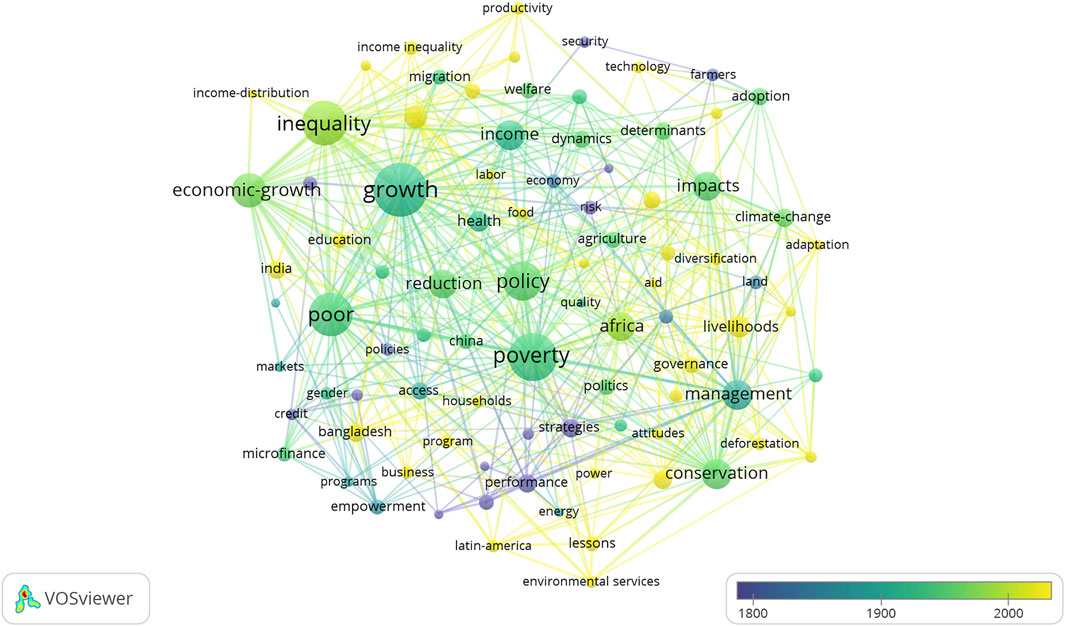

We set the minimum number of occurrences to 15, and 100 words with the greatest link strength are selected from the total of 2,774. As shown in Figure 8 , keywords plus generates 4 clusters. To our delight, each cluster does reflect the research priorities of each region.

FIGURE 8 . Keywords-plus co-occurrence cluster map.

The first cluster (red) reveals studies concerning livelihood, conservation, management, climate change and agriculture. These topics have strong interlinkage to Africa, suggesting that poverty reduction in Africa is often related to basic livelihood and ecology. The poor in Africa rely on the ecological conditions heavily as they are facing a more disadvantaged climate and resources. Therefore, their poverty reduction process is sometimes highly unstable and subject to considerable internal and external constraints. Stevenson and Irz (2009) concluded that the numerous studies presented almost no evidence of aquaculture reducing poverty directly.

The second cluster (green) represents studies focused on economic growth and income inequality, common in China and India. This pattern may imply that papers of this cluster focus on the economic conditions of the poor. Other studies in this cluster are related to migration, health, and welfare. The third cluster (blue) is the poverty reduction strategies on microfinance and empowerment, which are associated with Bangladesh where the Grameen Bank, one of the most notable and intensely researched microcredit programs, was founded ( McKernan, 2002 ). This cluster’s studies are interested in approaches such as business, markets, and education, to help the poor rise from poverty. The fourth cluster (yellow) contains studies of poverty reduction programs on environmental services in Latin America, where the environmental problem is intertwined with poverty traps.

Figure 9 shows the time trend of keywords-plus co-occurrence. Because the keywords plus are extracted from the cited references, they can reflect the changes in hotspots from relatively early to the most recent years. As can be seen, education, technology, and environmental services are the latest keywords in research on poverty reduction.

FIGURE 9 . Keywords-plus co-occurrence time trend map.

There are several limitations to our bibliometric analysis, though we undertake an extensive review of the literature. First, we inevitably lose a fraction of the literature. keywords and title are chosen as the criteria for helping precisely concentrate the search results on our subject. However, the Web of Science core collection on which our study relied is weak in the coverage of literature to some degree. Hence, there is a trade-off between the quantity and the quality of literature. We choose the latter, leading to an unclear restriction of the comprehensiveness of research. Second, we can identify recent research status but are not able to locate the Frontier accurately. Network mapping requires selecting a minimum occurrence threshold for including corresponding authors, keywords, and citations into the network. Because a certain number of citations or new hotspots take several years to be widely used and studied, this threshold may neglect these important data ( Linnenluecke et al., 2020 ). One possible solution is to manually examine the latest published papers in high-quality journals. Third, the mining of subfields is not deep enough. In other words, bibliometrics cannot sort out the main conclusions of literature on poverty reduction. For instance, we do not know whether the conclusion of different studies are consistent for the same poverty alleviation project. Neither do we know the exact mechanism of the anti-poverty program through bibliometric analysis, which limits the possibility of finding research points from controversial conclusions or mechanisms.

However, several points are worth taking into consideration for the future. To start with, poverty reduction is a natural interdisciplinary social science problem. Interdisciplinary has become a major research trend. Except applying cash transfer to ecological programs, associations are raised. We may discuss whether the combination of finance and ecology will bring positive benefits to financial stability, ecological protection, and poverty reduction by the means of capitalization of ecological resources or establishing the ecological bank. Our analysis suggests that some unheeded branch disciplines like human ethology are contributing to poverty reduction research as well. Thus, we need to investigate the interdisciplinary integration and the contribution of marginal disciplines on poverty reduction.

Then, more attention should be paid the intergenerational poverty. It requires researchers to extend the time span of observation and questionnaire investigation. Some work has been done. One example is the research of Hussain and Hanjra (2004) . They reviewed literature and clarified that advances in irrigation technologies, such as micro-irrigation systems, have strong anti-poverty potential, alleviating both temporary and chronic poverty. Another example is the research of Jones (2016) , which indicated that conditional cash transfers (CCTs) could indeed interrupt the intergenerational cycle of poverty through human capital investments. However, there remains a lot of work to be done for preventing the next generation from returning to poverty in this turbulent period. In a related matter, the role of education in isolating intergenerational poverty or returning to the poverty trap should be highlighted. What kind of education would more effectively help families out of poverty, quality education or vocational skill education? How to allocate educational resources effectively? For poor students, what kind of psychological intervention in education is needed to mitigate the impact of native families and help them grow up confidently? Lots of questions waiting for empirical answering, yet we note that the educational journal only took a little fraction of the total journals in Section 4.3.2.

Next, poverty does exist in prosperous conurbations though the focal point obtained from keywords analysis is “rural area”. Nevertheless, both the slums in the center of big cities and circulative flowing refugees are experiencing more relative deprivation, representing a state of instability. Chamhuri et al. (2012) reviewed the objects, causes, and policies of urban poverty. Exploring how to lift a particular small economic low-lying area out of poverty is also of great significance. Follow-up researches should keep up.

Moreover, poverty alleviation needs to be based on individual or group-specific characteristics to some degree. It is not feasible to implement a unified poverty alleviation policy on a large scale. Exquisitely designed randomized controlled trials are used to reveal the heterogeneous influence of poverty alleviation programs. Haushofer and Shapiro (2016) compared the difference between monthly transfers and one-time lump-sum transfers. The subdivision research on the effect of poverty reduction programs should be strengthened. We imagine that a model may be formed to predict the total poverty reduction effects of different policies in the various region to obtain an optimized strategy of “No Poverty” in the future.

Lastly, exploring whether poverty reduction will be contradictory or coordinate with other SDGs might be a popular direction. About the literature review, two aspects can be improved. The first is merging with other databases to compare the loss of the trade-off between quality and quantity. Next, subsequent literature reviews need to explore how to better combine manual literature collation and bibliometrics, especially when the subject is a large topic.

Poverty reduction is one of the objectives of welfare economics and development economics. It is a classic and lasting topic and has recently come into the limelight. Poverty reduction studies in the 21st century are usually based on specific poverty alleviation projects or policies in developing countries. Researchers examine numerous topics, including whether the target audience has been precisely identified and covered in the design and implementation process, whether poverty reduction projects have been proved effective, what mechanisms have contributed to the success of poverty reduction projects, and what caused their failure. The aim of this paper is to summarize the amount, growth trajectory, citation, and geographic distribution of the poverty reduction literature, map the intellectual structure, and highlight emerging key areas in the research domain using the bibliometric method. We use the VOSviewer software and the R language as tools to analyze 2,459 articles published since 2000.

We have several conclusions. First, the 21st century is a period of booming research on poverty reduction, and the number of publications has increased sharply since 2015. Second, in affiliation analysis, Development in Practice and World Development are the top publications. The most frequently cited source of co-citations are World Development , Ecology Economics, Journal of Business Ethics, and Annals of Tourism Research , respectively the centers of the fields of economics, energy, the environment, and ecology, business, and tourism. Third, there are differences in the national and regional distribution of literature, based on the number of publications and citations. The United States led both the publication list and the total citation list, followed by the United Kingdom, China, and South Africa. Yet, there is a huge variation in the number of citations, with the United States and the United Kingdom having almost 5 to 6 times more citations than China and South Africa. In terms of average citations, Kenya is the best performer. The average citation amount in China is low, implying that Chinese scholars need to improve the quality of their literature. Fourth, in the keyword analysis, policy discussion and impact estimation are the two major themes. The keywords related to poverty reduction are different among different disciplines. Economics pays more attention to inequality and growth, while environmental disciplines pay more attention to protection and management. This may suggest that strengthening the cooperation between disciplines will lead to more diversified research perspectives. Fifth, in the co-author analysis, international cooperation is usually related to geographical location. For example, there is a large amount of cooperation between Europe and Africa, within Asia, and between North and South America. At the same time, poverty reduction research often shows the cooperative patterns of developed and developing countries. Last, in the co-keyword analysis, four clusters reflect the research priorities of each region. Poverty reduction in Africa is often related to basic livelihood and ecology. The economic conditions of the poor are the concerns of research in China and India. The South Asia region is also the location of microcredit program experiments. Poverty traps are intertwined with environmental problems in Latin America’s literature.

Our findings also offer inspiration for the future. There may be a need to investigate the interdisciplinary integration. Intergenerational and urban poverty deserve attention. The heterogeneous design of poverty alleviation strategies needs to be further deepened. It might be a popular direction to figure out whether poverty reduction will be contradictory with other SDGs and conduct scenario simulation. We identify shortcomings as well. Finally, precisely identifying research frontiers requires further exploration.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

This work is supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (grant number 72022009).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2021.754181/full#supplementary-material

1 The extreme poverty criterion set by World Bank is 1.9$ a day in purchasing power parties (PPP), https://www.worldbank.org/en/research/brief/policy-research-note-03-ending-extreme-poverty-and-sharing-prosperity-progress-and-policies . The China poverty alleviation target in 2020 is to eliminate absolute poverty, which is defined as living less than 2,300 yuan per person per day at 2010 constant prices. In addition to living above the absolute poverty line, people who must reached other five qualitative criteria can be calculated getting rid of absolute poverty, which is no worries about food, clothing, basic medical care, compulsory education and housing safety

2 Jingzhunfupin is a general term of Chinese targeted poverty alleviation work model. Opposite to the haploid poverty alleviation, different assistance policies will be formulated according to the different category of poverty, distinctive causes, dissimilar background of poor households and their divergent living environment

3 https://enapp.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202102/26/AP60382a17a310f03332f97555.html . https://www.bbc.com/news/56213271

4 https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/poverty/overview

5 The global Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) is developed by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative (OPHI) since 2010. It has been published annually by OPHI and in the Human Development Reports (HDRs) ever since. https://ophi.org.uk/multidimensional-poverty-index/

6 Relative poverty is another poverty measurement to reflect the underlying economic gradient. It is induced from the relative deprivation theory. Countries set the relative poverty line at a constant proportion of the country or year-specific mean (or median) income in practice ( https://doi.org/10.1162/REST_a_00127 )

7 This paper mainly found that eradicating extreme poverty, i.e., moving people to an income above $1.9 purchasing power parity (PPP) a day, does not jeopardize the climate target. That is to say, the climate target and no poverty goal is consistent and coordinated

8 This paper indicated that Payments for Environmental Services may reduce poverty mainly by making payments to poor natural resource managers in upper watersheds. The effects depend on how many participants are poor, the poor’s ability to participate, and the amounts paid

9 8–7 plan is the second wave of China’s poverty alleviation program. The Leading Group renewed poverty line and the National Poor Counties list in 1993. Targeted counties received three major interventions: credit assistance, budgetary grants for investment and public employed projects (i.e., Food-for-Work).

10 In the College Graduate Village Officials (CGVOs) program, the government hire outstanding graduates to work in the rural areas, for example as the village committee secretary, to help rural development and alleviate poverty. In this paper, the College Graduate Village Officials assisted eligible poor households to understand and apply for relevant subsidies, which reduced elite capture of pro-poor programs and move forward poverty alleviation process

11 The Tayssir Project was labeled the Education Support Program, sending a positive signal of its educative value

Adams, R. H., and Page, J. (2005). Do international Migration and Remittances Reduce Poverty in Developing Countries? World Develop. 33, 1645–1669. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2005.05.004

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Addison, T., Hulme, D., and Kanbur, R. (2008), Poverty Dynamics: Measurement and Understanding from an Interdisciplinary Perspective. Working Paper No. 19. Brooks World Poverty Institute . Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1246882 .

Google Scholar

Alix-Garcia, J., McIntosh, C., Sims, K. R. E., and Welch, J. R. (2013). The Ecological Footprint of Poverty Alleviation: Evidence from Mexico's Oportunidades Program. Rev. Econ. Stat. 95, 417–435. doi:10.1162/REST_a_00349

Alix-Garcia, J. M., Sims, K. R. E., and Yañez-Pagans, P. (2015). Only One Tree from Each Seed? Environmental Effectiveness and Poverty Alleviation in Mexico's Payments for Ecosystem Services Program. Am. Econ. J. Econ. Pol. 7, 1–40. doi:10.1257/pol.20130139

Amarante, V., Brun, M., and Rossel, C. (2020). Poverty and Inequality in Latin America's Research Agenda: A Bibliometric Review. Dev. Pol. Rev. 38, 465–482. doi:10.1111/dpr.12429

Banerjee, A., Duflo, E., Glennerster, R., and Kinnan, C. (2015). The Miracle of Microfinance? Evidence from a Randomized Evaluation. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 7, 22–53. doi:10.1257/app.20130533

Banerjee, A., Duflo, E., Goldberg, N., Karlan, D., Osei, R., Parienté, W., ..., , Shapiro, J., Thuysbaert, B., and Udry, C. (2015). A Multifaceted Program Causes Lasting Progress for the Very Poor: Evidence from Six Countries. Science 348, 1260799. doi:10.1126/science.1260799

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Banerjee, A. V., and Duflo, E. (2007). The Economic Lives of the Poor. J. Econ. Perspect. 21, 141–167. doi:10.1257/089533007780095556

Bardhan, P., and Mookherjee, D. (2005). Decentralizing Antipoverty Program Delivery in Developing Countries. J. Public Econ. 89, 675–704. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2003.01.001

Beck, T., Demirgüç-Kunt, A., and Levine, R. (2007). Finance, Inequality and the Poor. J. Econ. Growth 12, 27–49. doi:10.1007/s10887-007-9010-6

Benhassine, N., Devoto, F., Duflo, E., Dupas, P., and Pouliquen, V. (2015). Turning a Shove into a Nudge? A "Labeled Cash Transfer" for Education. Am. Econ. J. Econ. Pol. 7, 86–125. doi:10.1257/pol.20130225

Bibi, S., and Duclos, J.-Y. (2007). Equity and Policy Effectiveness with Imperfect Targeting. J. Develop. Econ. 83, 109–140. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2005.12.001

Bourguignon, F., and Chakravarty, S. R. (2019). “The Measurement of Multidimensional Poverty,” in Poverty, Social Exclusion and Stochastic Dominance. Themes in Economics (Theory, Empirics, and Policy) . Editor S. Chakravarty (Singapore: Springer ), 83–107. doi:10.1007/978-981-13-3432-0_7

Callon, M., Courtial, J.-P., Turner, W. A., and Bauin, S. (1983). From Translations to Problematic Networks: An Introduction to Co-word Analysis. Soc. Sci. Inf. 22, 191–235. doi:10.1177/053901883022002003

Campos, F., Frese, M., Goldstein, M., Iacovone, L., Johnson, H. C., McKenzie, D., et al. (2017). Teaching Personal Initiative Beats Traditional Training in Boosting Small Business in West Africa. Science 357, 1287–1290. doi:10.1126/science.aan5329

Chamhuri, N. H., Karim, H. A., and Hamdan, H. (2012). Conceptual Framework of Urban Poverty Reduction: A Review of Literature. Proced. - Soc. Behav. Sci. 68, 804–814. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.12.268

Chen, S., and Ravallion, M. (2013). More Relatively-Poor People in a Less Absolutely-Poor World. Rev. Income Wealth 59 (1), 1–28. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4991.2012.00520.x

Collier, P., and Dollar, D. (2002). Aid Allocation and Poverty Reduction. Eur. Econ. Rev. 46, 1475–1500. doi:10.1016/S0014-2921(01)00187-8

Cornwall, A., and Brock, K. (2005). What Do Buzzwords Do for Development Policy? a Critical Look at 'participation', 'empowerment' and 'poverty Reduction'. Third World Q. 26, 1043–1060. doi:10.1080/01436590500235603

Datt, G., and Ravallion, M. (1992). Growth and Redistribution Components of Changes in Poverty Measures. J. Develop. Econ. 38, 275–295. doi:10.1016/0304-3878(92)90001-P

Daw, T., Brown, K., Rosendo, S., and Pomeroy, R. (2011). Applying the Ecosystem Services Concept to Poverty Alleviation: the Need to Disaggregate Human Well-Being. Envir. Conserv. 38, 370–379. doi:10.1017/S0376892911000506

Dollar, D., and Kraay, A. (2002). Growth Is Good for the Poor. J. Econ. Growth 7, 195–225. doi:10.1023/A:1020139631000

Foster, J., Greer, J., and Thorbecke, E. (1984). A Class of Decomposable Poverty Measures. Econometrica 52, 761–766. doi:10.2307/1913475

Galiani, S., and McEwan, P. J. (2013). The Heterogeneous Impact of Conditional Cash Transfers. J. Public Econ. 103, 85–96. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2013.04.004

González-Alcaide, G., Calafat, A., Becoña, E., Thijs, B., and Glänzel, W. (2016). Co-Citation Analysis of Articles Published in Substance Abuse Journals: Intellectual Structure and Research Fields (2001-2012). J. Stud. Alcohol. Drugs 77, 710–722. doi:10.15288/jsad.2016.77.710

Grindle, M. S. (2004). Good Enough Governance: Poverty Reduction and Reform in Developing Countries. Governance 17, 525–548. doi:10.1111/j.0952-1895.2004.00256.x

Haushofer, J., and Shapiro, J. (2016). The Short-Term Impact of Unconditional Cash Transfers to the Poor: Experimental Evidence from Kenya*. Q. J. Econ. 131, 1973–2042. doi:10.1093/qje/qjw025

He, G., and Wang, S. (2017). Do college Graduates Serving as Village Officials Help Rural China. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 9, 186–215. doi:10.1257/app.20160079

Huang, D., and Ying, Z. (2018). A Review on Precise Poverty Alleviation by Introducing Market Mechanism in a Context Dominated by Government, 2nd International Forum on Management, Education and Information Technology Application . Paris: Atlantis Press , 110–117. doi:10.2991/ifmeita-17.2018.19

Hubacek, K., Baiocchi, G., Feng, K., and Patwardhan, A. (2017). Poverty Eradication in a Carbon Constrained World. Nat. Commun. 8 (1), 1–9. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-00919-4

Hulme, D., and Shepherd, A. (2003). Conceptualizing Chronic Poverty. World Develop. 31, 403–423. doi:10.1016/S0305-750X(02)00222-X

Hussain, I., and Hanjra, M. A. (2004). Irrigation and Poverty Alleviation: Review of the Empirical Evidence. Irrig. Drain. 53, 1–15. doi:10.1002/ird.114

Jalan, J., and Ravallion, M. (2003). Estimating the Benefit Incidence of an Antipoverty Program by Propensity-Score Matching. J. Business Econ. Stat. 21, 19–30. doi:10.1198/073500102288618720

Jones, H. (2016). More Education, Better Jobs? A Critical Review of CCTs and Brazil's Bolsa Família Programme for Long-Term Poverty Reduction. Soc. Pol. Soc. 15, 465–478. doi:10.1017/S1474746416000087

Karlan, D., and Valdivia, M. (2011). Teaching Entrepreneurship: Impact of Business Training on Microfinance Clients and Institutions. Rev. Econ. Stat. 93, 510–527. doi:10.1162/REST_a_00074

Karlan, D., and Zinman, J. (2011). Microcredit in Theory and Practice: Using Randomized Credit Scoring for Impact Evaluation. Science 332, 1278–1284. doi:10.1126/science.1200138

Karnani, A. (2007). The Mirage of Marketing to the Bottom of the Pyramid: How the Private Sector Can Help Alleviate Poverty. Calif. Manage. Rev. 49, 90–111. doi:10.2307/41166407

Kleven, H. J., and Kopczuk, W. (2011). Transfer Program Complexity and the Take-Up of Social Benefits. Am. Econ. J. Econ. Pol. 3, 54–90. doi:10.1257/pol.3.1.54

Kwan, C., Walsh, C. A., and Donaldson, R. (2018). Old Age Poverty: A Scoping Review of the Literature. Cogent Soc. Sci. 4, 1478479–1478521. doi:10.1080/23311886.2018.1478479

Li, R., Shan, Y., Bi, J., Liu, M., Ma, Z., Wang, J., et al. (2021). Balance between Poverty Alleviation and Air Pollutant Reduction in China. Environ. Res. Lett. 16 (9), 094019. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/ac19db

Linnenluecke, M. K., Marrone, M., and Singh, A. K. (2020). Conducting Systematic Literature Reviews and Bibliometric Analyses. Aust. J. Manage. 45, 175–194. doi:10.1177/0312896219877678

Ludwig, J., Duncan, G. J., Gennetian, L. A., Katz, L. F., Kessler, R. C., Kling, J. R., et al. (2012). Neighborhood Effects on the Long-Term Well-Being of Low-Income Adults. Science 337, 1505–1510. doi:10.1126/science.1224648

Mahembe, E., Odhiambo, N. M., and Read, R. (2019). Foreign Aid and Poverty Reduction: A Review of International Literature. Cogent Soc. Sci. 5, 1625741. doi:10.1080/23311886.2019.1625741

Mani, A., Mullainathan, S., Shafir, E., and Zhao, J. (2013). Poverty Impedes Cognitive Function. Science 341, 976–980. doi:10.1126/science.1238041

Maulu, S., Hasimuna, O. J., Mutale, B., Mphande, J., and Siankwilimba, E. (2021). Enhancing the Role of Rural Agricultural Extension Programs in Poverty Alleviation: A Review. Cogent Food Agric. 7, 1886663. doi:10.1080/23311932.2021.1886663

Mbuyisa, B., and Leonard, A. (2017). The Role of ICT Use in SMEs towards Poverty Reduction: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Int. Dev. 29, 159–197. doi:10.1002/jid.3258

McKernan, S.-M. (2002). The Impact of Microcredit Programs on Self-Employment Profits: Do Noncredit Program Aspects Matter. Rev. Econ. Stat. 84, 93–115. doi:10.1162/003465302317331946

Meinzen-Dick, R., Quisumbing, A., Doss, C., and Theis, S. (2019). Women's Land Rights as a Pathway to Poverty Reduction: Framework and Review of Available Evidence. Agric. Syst. 172, 72–82. doi:10.1016/j.agsy.2017.10.009

Meng, L. (2013). Evaluating China's Poverty Alleviation Program: a Regression Discontinuity Approach. J. Public Econ. 101, 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2013.02.004

Merediz-Solà, I., and Bariviera, A. F. (2019). A Bibliometric Analysis of Bitcoin Scientific Production. Res. Int. Business Finance 50, 294–305. doi:10.1016/j.ribaf.2019.06.008

Niehaus, P., Atanassova, A., Bertrand, M., and Mullainathan, S. (2013). Targeting with Agents. Am. Econ. J. Econ. Pol. 5, 206–238. doi:10.1257/pol.5.1.206

Pagiola, S., Arcenas, A., and Platais, G. (2005). Can Payments for Environmental Services Help Reduce Poverty? an Exploration of the Issues and the Evidence to Date from Latin America. World Develop. 33, 237–253. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2004.07.011

Park, A., Wang, S., and Wu, G. (2002). Regional Poverty Targeting in China. J. Public Econ. 86, 123–153. doi:10.1016/S0047-2727(01)00108-6

Pritchard, A. (1969). Oecologia. J. Doc. 50, 348–349. doi:10.2307/1934868

Sedlmayr, R., Shah, A., and Sulaiman, M. (2020). Cash-plus: Poverty Impacts of Alternative Transfer-Based Approaches. J. Develop. Econ. 144, 102418. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2019.102418

Sen, A. (1999). “Development as freedom,” in The Globalization and Development Reader: Perspectives on Development and Global Change . Editors J. T. Roberts, A. B. Hite, and N. Chorev (New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons ), 525.

Sims, K. R. E., and Alix-Garcia, J. M. (2017). Parks versus PES: Evaluating Direct and Incentive-Based Land Conservation in Mexico. J. Environ. Econ. Manage. 86, 8–28. doi:10.1016/j.jeem.2016.11.010

Small, H. (1973). Co-citation in the Scientific Literature: A New Measure of the Relationship between Two Documents. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. 24, 265–269. doi:10.1002/asi.4630240406

Stevenson, J. R., and Irz, X. (2009). Is Aquaculture Development an Effective Tool for Poverty Alleviation? A Review of Theory and Evidence. Cah. Agric. 18, 292–299. doi:10.1684/agr.2009.0286

Su, Y., Yu, Y., and Zhang, N. (2020). Carbon Emissions and Environmental Management Based on Big Data and Streaming Data: A Bibliometric Analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 733, 138984. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138984

Van Eck, N. J., and Waltman, L. (2010). Software Survey: VOSviewer, a Computer Program for Bibliometric Mapping. Scientometrics 84, 523–538. doi:10.1007/s11192-009-0146-3

Wilson, D. C., Velis, C., and Cheeseman, C. (2006). Role of Informal Sector Recycling in Waste Management in Developing Countries. Habitat Int. 30, 797–808. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2005.09.005

Zhang, J., Yu, Q., Zheng, F., Long, C., Lu, Z., and Duan, Z. (2016). Comparing Keywords Plus of WOS and Author Keywords: A Case Study of Patient Adherence Research. J. Assn Inf. Sci. Tec 67, 967–972. doi:10.1002/asi.23437

Zhang, X., Yu, Y., and Zhang, N. (2020). Sustainable Supply Chain Management under Big Data: a Bibliometric Analysis. Jeim 34, 427–445. doi:10.1108/JEIM-12-2019-0381

Zhou, D., Cai, K., and Zhong, S. (2021). A Statistical Measurement of Poverty Reduction Effectiveness: Using China as an Example. Soc. Indic. Res. 153, 39–64. doi:10.1007/s11205-020-02474-w

Keywords: poverty reduction, bibliometric analysis, VOSviewer, sustainable development goals, 21st century

Citation: Yu Y and Huang J (2021) Poverty Reduction of Sustainable Development Goals in the 21st Century: A Bibliometric Analysis. Front. Commun. 6:754181. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2021.754181

Received: 06 August 2021; Accepted: 01 October 2021; Published: 18 October 2021.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2021 Yu and Huang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yanni Yu, [email protected] ; Jinghong Huang, [email protected]

† These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 13 June 2024

From poverty to prosperity: assessing of sustainable poverty reduction effect of “welfare-to-work” in Chinese counties

- Feng Lan 1 , 2 ,

- Weichao Xu 1 ,

- Weizeng Sun 3 &

- Xiaonan Zhao 1

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 11 , Article number: 758 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

1108 Accesses

1 Altmetric

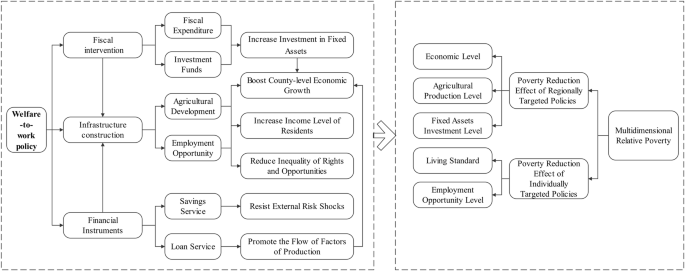

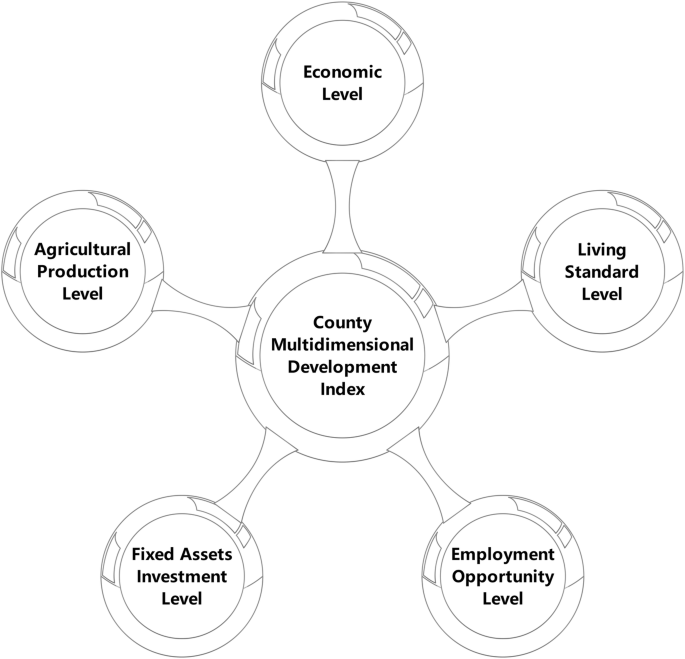

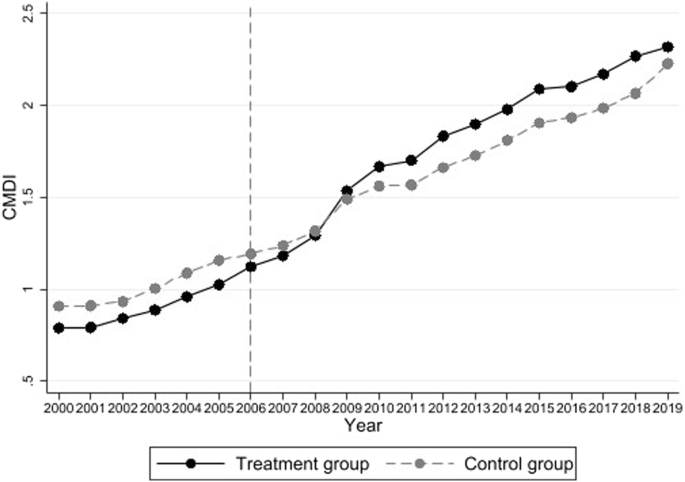

Metrics details

- Development studies

- Social policy

The “welfare-to-work” program is a comprehensive supportive policy in the 14th five-year plan period in China. In this paper, a systematical assessment of the long-run effectiveness of the welfare-to-work policy on poverty reduction is of great significance to stimulate the internal impetus of people who are lifted out of poverty to achieve income growth and prosperity and promote regional economic development. Based on the data at the county (city) level in China from 2000 to 2019 and the sustainable development theory, in this paper, a county-relative poverty evaluation system was constructed. Besides, the double difference method was employed to evaluate the effect of the welfare-to-work policy on poverty reduction and test its action mechanism. The findings are as follows: (1) the welfare-to-work policy has a significant poverty reduction effect and presents an inverted “U” shape. In addition, significant achievements have been made in “maintaining employment stability, ensuring income, strengthening skills, and supporting the economy” ; (2) the welfare-to-work policy boosts poverty reduction in counties through infrastructure construction, fiscal intervention, and financial tools; however, the financial tools play a positive role in poverty reduction in the northwest region and suppressed role in the southwest region, and has an insignificant effect in the central region; and (3) there are differences in the effect of poverty alleviation policies of the counties with different sustainable development levels, and the regions with higher development level have a stronger driving effect.

Similar content being viewed by others

Investigation of multidimensional poverty in Pakistan at the national, regional, and provincial level

The effects of China’s poverty eradication program on sustainability and inequality

Do workers benefit from economic upgrading in the Pearl River Delta, China?

Introduction.

In 2021, China has scored a competitive victory in the fight against poverty. The final 98.99 million impoverished rural residents living under the current poverty line have all been lifted out of poverty. All 832 impoverished counties across the country and 128,000 impoverished villages have been removed from the poverty list Footnote 1 . Regional overall poverty has been resolved, which marks that China’s poverty governance has entered a new stage from absolute poverty to relative poverty, and from income poverty to multidimensional poverty. Relative poverty and multidimensional poverty have become new forms of poverty in China (Xu et al. 2021 ).

China’s anti-poverty focus has shifted from targeted poverty alleviation in absolute poor areas to comprehensive measures to promote high-quality development in relatively poor areas. The limited ability of the relatively poor population to obtain various livelihood capital also reduces the range of livelihood activities, and aggravates the livelihood risk and vulnerability. These factors will affect the economic development of relatively poor areas and the ability of rural populations to increase their income, and the long-term and complexity of this external environment also determine the long-term sustainability of consolidating and expanding the achievements of poverty alleviation.

Since ancient times, China has had the practice of “providing employment as a form of relief”. Since 1984, welfare-to-work, as a social and economic policy, has played an important role in poverty alleviation and development. Nowadays, with the transformation of China’s anti-poverty focus from the governance of absolute poverty to the high-quality development of relatively poor areas. The welfare-to-work policy not only has the attribute of poverty alleviation, but also has the overlapping role of social welfare and economic development, maximizing the release of the effects of the policy and activating the endogenous power of county economic development. On the one hand, it can be used to resist the impact of unfavorable factors and emergencies such as the COVID-19 pandemic, earthquakes, and tsunamis. Welfare-to-work policy can effectively play the role of “relief” in the process of flood control and post-disaster recovery. Compared with direct subsidies, welfare-to-work further mobilizes the enthusiasm of the broad masses of peasants to participate in the construction of rural public infrastructure and give full play to the investment of government for supporting agriculture. On the other hand, aiming at the employment needs of low-income groups, it provided timely payment of labor remuneration, and employment skills training. With compulsory and welfare means, it enhanced the capacity and subjective motivation of poverty-stricken people and low-income groups, thus encouraging them to participate in the competition.

Through data analysis, it was found that since the implementation of the “Welfare-to-work” policy in different regions, the effects have not been the same. For instance, during the implementation process, the phenomenon of emphasizing construction while neglecting relief has come into existence. Besides, influenced by the factors in regional development level, geographical restrictions, and population flow, the current labor force has lower quality and insufficient skills and thus achieves an unsatisfactory effect on employment and income growth. Although these areas have all been lifted out of poverty under the country’s targeted poverty alleviation policy, once impacted by external uncertainties, the obtained achievements in poverty alleviation will be irrevocably lost.

Therefore, what kind of impact does the sustainability of poverty reduction performance of the welfare-to-work policy have? Is there heterogeneity in the poverty reduction effect of the welfare-to-work policy in different districts and counties? What is the role of a welfare-to-work policy in poverty reduction?

In this paper, a multi-dimensional relative poverty evaluation index system was constructed and the poverty reduction effect of the “welfare-to-work” policy was evaluated by the method of double difference (DID). In addition, the panel regression model was constructed to explore the mechanism of poverty reduction, and the Shapley method was used to quantify the contribution of mechanism variables to the poverty reduction effect. The study has several important findings. First of all, the cash-for-work policy effectively promotes poverty reduction in counties, and the higher the level of local development, the more significant the poverty reduction effect. The results are still valid after robustness testing. Second, policies promote poverty reduction at the county level through infrastructure construction, fiscal intervention, and financial instruments, but the contribution of different variables in different regions is different.

The remainder of this study is arranged as follows. Section 2 “Literature review and research hyptothesis” provides a literature review and research hypothesis. Section 3 “Research design” describes our empirical design. Section 4 “Analysis of empirical results” reports our empirical results and robustness tests. Section 5 “Test of action mechanism” reports the quantitative results of the mechanism of action. Finally, we provide a summary.

Literature review and research hypothesis

Evolution of welfare-to-work policy.

(1) From 1949 to 1983: the stage with a focus on disaster relief. At the First and Second National Civil Affairs work conference, it was emphasized that in disaster relief work, the principles of overcoming adversity through greater production, saving grain to tide over a lean year, holding on to mutual assistance, work relief, and supplementary necessary government relief should be encouraged. However, in accordance with the statement of the National Civil Affairs Conference in 1953, as the following continuous various projects in economic construction in China would inevitably attract the participation of victims, so the Welfare-to-work policy was removed from the disaster relief policy. At this stage, the planned economy system not only strengthened the government’s ability to organize disaster victims to carry out self-rescue action but also endowed the welfare-to-work policy and other policies with distinctive epochal features (Zhu, 2021 ). Specifically, the Welfare-to-work policy mainly focuses on the unemployed population and disaster relief. In addition, with efforts of supply optimization manpower allocation, and material and financial resources supply, the government organized victims in the form of mutual assistance and cooperation and built some engineering facilities in flood control, drainage, irrigation, and power generation, which have promoted the recovery of production and reconstruction of homes while providing disaster relief.

(2) From 1984 to 2000: the early stage of poverty alleviation and development. With the economic reform, poverty has been included as an important part of social and economic development. In 1984, China began to regard welfare-to-work as a means of alleviating poverty, and successively implemented six large-scale welfare-to-work programs, namely “grain and cotton cloth related welfare-to-work program”, “medium-and low-grade industrial products related welfare-to-work program”, “industrial products related welfare-to-work program”, “grain related welfare-to-work program”, “river control related welfare-to-work program” and “state-owned poor farms related welfare-to-work program”. In other words, since 1984, China has organized the impoverished people to carry out infrastructure construction in the fields, roads, rivers, houses, and toilets and has paid for grain, cotton, cotton cloth and industrial products to workers as labor remuneration. This measure not only provides employment opportunities and achieves income growth for poor workers but also improves infrastructure and public services in poor areas. In 1990, the State Council issued the Opinions on the Arrangement of Industrial Products for Welfare to Work from 1990 to 1992. According to the Opinions, 1.5 billion yuan of industrial products were used for the labor remuneration for workers in the construction of the welfare-to-work program; during the eighth five-year plan period, the Chinese government invested 1 billion kilograms of grain or equivalent industrial products per year in the Welfare-to-work program in poor areas; and in 1996, the welfare-to-work program was supported by financial funds instead of the form of in-kind cash conversion. In 1998, in the context of the financial crisis, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) issued measures to support the welfare-to-work program with treasury bonds, which solved the problem of expanding domestic demand. As an important part of the central poverty alleviation fund, the proportion of welfare-to-work funds increased from 15.38% to 37.04% in the ten years from 1986 to 1996, during which the acceleration of infrastructure construction in poor areas became the main operation mode of the welfare-to-work policy. At this time, the Welfare-to-work system not only had the function of disaster relief but also promoted the construction of local infrastructure.

(3) From 2000 to 2020: the special-purpose poverty alleviation policy stage. In the 21st century, the welfare-to-work program gradually has developed with “fine, small and deep” characteristics, with a focus on the implementation in a certain region or in-depth research on the analysis of welfare-to-work on the system (Shen, 2018 ). In December 2005, the NDRC issued the National Administrative Measures for welfare-to-work Policy, which highlighted the funds' management, project implementation, and organizational management of the welfare-to-work program, thereby improving the implementation performance of the policy. In 2011, to improve the quality of cultivated land, strengthen infrastructure construction, enhance the ability to withstand natural disasters, and consolidate the foundation of economic development in poor areas, the Chinese government issued the Outline for Poverty Alleviation and Development in China’s Rural Areas (2011–2020), in which the welfare-to-work program was included as a special-purpose poverty alleviation policy measure. In December 2014, to meet the requirements of rural poverty alleviation under the new situation, the NDRC launched the revision of the administrative measures for welfare-to-work policy. In 2016, the NDRC issued the National “13th five-year plan” for the welfare-to-work program, taking small and medium-sized infrastructure in rural areas the focus of the welfare-to-work program. According to the work plan, the welfare-to-work program should be transformed from “adopting a deluge of strong stimulus policies” to “precision regulation policies”, and a new model of poverty alleviation with asset income featuring “changing assets into equity, poor households into shareholders” should be innovated. In June 2019, the NDRC issued guiding opinions on further leveraging the role of welfare-to-work policies to help win the battle against poverty, which called for the continuous focus on supporting deeply impoverished areas such as the “three regions and three prefectures” to win the battle against poverty as scheduled and consolidate poverty alleviation achievements in poor areas. In July 2019, the NDRC issued Opinions on further adhering to the original purpose of “Relief” and giving full play to the function of the welfare-to-work policy, which underscored the importance of comprehensively expanding a variety of relief modes, relying on welfare-to-work projects to extensively carry out employment skills training and public welfare position development, and exploring the implementation of quantitative dividends through asset share conversion. In November 2020, the NDRC and nine other departments issued opinions on actively promoting welfare-to-work policy in the field of agricultural and rural infrastructure construction, requiring that the welfare-to-work policy should be actively promoted in the fields of rural production and life, transportation, water conservancy infrastructure, cultural tourism infrastructure, forestry, and grassland infrastructure construction, so as to improve rural production and living conditions, which has played an important role in consolidating the achievements of poverty alleviation.

(4) From 2021 to present: multifunctional comprehensive stage. In July 2021, the NDRC issued the National “14th Five-Year Plan” for the welfare-to-work program, which comprehensively expands the implementation areas, implementation functions, beneficiary groups, construction areas, and relief modes of the policy in the next five years. In July 2022, the NDRC issued a work plan on vigorously implementing welfare-to-work policy in key engineering projects to promote employment and income growth of local people. In the work plan, the NDRC emphasized that vigorously implementing the Welfare-to-work policy in key engineering projects is an important measure to promote effective investment, ensure employment stability and people’s well-being, stimulate county consumption, and stabilize the economic market, which will drive the people to share in the fruits of reform and development. In January 2023, in the context of a new journey and new requirements in the new era, the NDRC revised the National Administrative Measures for welfare-to-work policy. The NDRC stressed that on the one hand, we should stick to the original purpose of “Relief”, insist on helping people who have talent and poverty problems, and adhere to the principles of earning more from more work and getting rich through hard work to enhance the internal impetus of income growth and prosperity. On the other hand, we should strengthen the employment assistance for the people in difficulty, and promote common prosperity.