John Money Gender Experiment: Reimer Twins

Julia Simkus

Editor at Simply Psychology

BA (Hons) Psychology, Princeton University

Julia Simkus is a graduate of Princeton University with a Bachelor of Arts in Psychology. She is currently studying for a Master's Degree in Counseling for Mental Health and Wellness in September 2023. Julia's research has been published in peer reviewed journals.

Learn about our Editorial Process

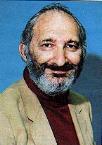

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

The John Money Experiment involved David Reimer, a twin boy raised as a girl following a botched circumcision. Money asserted gender was primarily learned, not innate.

However, David struggled with his female identity and transitioned back to male in adolescence. The case challenged Money’s theory, highlighting the influence of biological sex on gender identity.

- David Reimer was born in 1965; he had a MZ twin brother. When he was 8 months old his penis was accidentally cut off during surgery.

- His parents contacted John Money, a psychologist who was developing a theory of gender neutrality. His theory claimed that a child would take the gender identity he/she was raised with rather than the gender identity corresponding to the biological sex.

- David’s parents brought him up as a girl and Money wrote extensively about this case claiming it supported his theory. However, Brenda as he was named was suffering from severe psychological and emotional difficulties and in her teens, when she found out what had happened, she reverted back to being a boy.

- This case study supports the influence of testosterone on gender development as it shows that David’s brain development was influenced by the presence of this hormone and its effects on gender identity was stronger that the influence of social factors.

What Did John Money Do To The Twins

David Reimer was an identical twin boy born in Canada in 1965. When he was 8 months old, his penis was irreparably damaged during a botched circumcision.

John Money, a psychologist from Johns Hopkins University, had a prominent reputation in the field of sexual development and gender identity.

David’s parents took David to see Dr. Money at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, where he advised that David be “sex reassigned” as a girl through surgical, hormonal, and psychological treatments.

John Money believed that gender identity is primarily learned through one’s upbringing (nurture) as opposed to one’s inborn traits (nature).

He proposed that gender identity could be changed through behavioral interventions, and he advocated that gender reassignment was the solution for treating any child with intersex traits or atypical sex anatomies.

Dr. John Money argued that it’s possible to habilitate a baby with a defective penis more effectively as a girl than a boy.

At the age of 22 months, David underwent extensive surgery in which his testes and penis were surgically removed and rudimentary female genitals were constructed.

David’s parents raised him as a female and gave him the name Brenda (this name was chosen to be similar to his birth name, Bruce). David was given estrogen during adolescence to promote the development of breasts.

He was forced to wear dresses and was directed to engage in typical female norms, such as playing with dolls and mingling with other girls.

Throughout his childhood, David was never informed that he was biologically male and that he was an experimental subject in a controversial investigation to bolster Money’s belief in the theory of gender neutrality – that nurture, not nature, determines gender identity and sexual orientation.

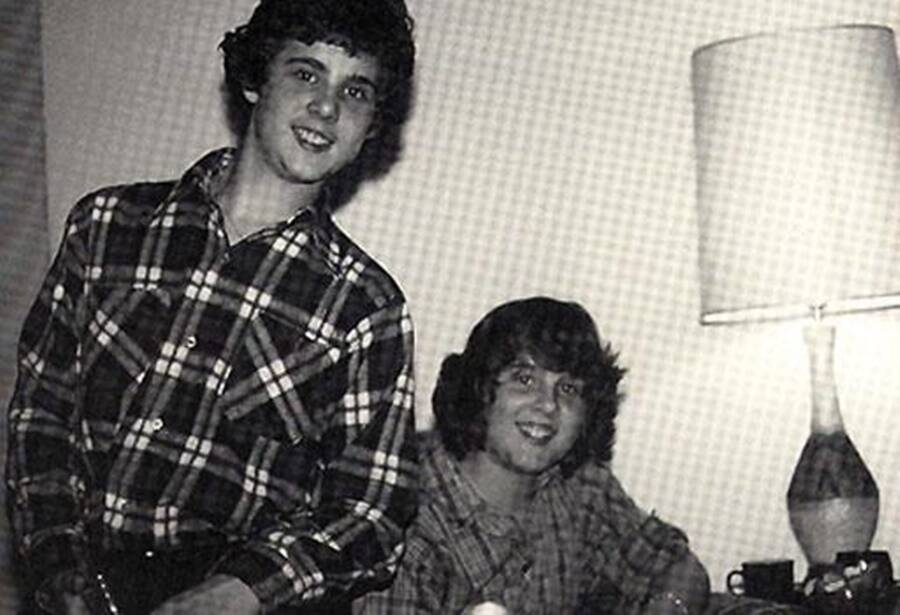

David’s twin brother, Brian, served as the ideal control because the brothers had the same genetic makeup, but one was raised as a girl and the other as a boy. Money continued to see David and Brian for consultations and checkups annually.

During these check-ups, Money would force the twins to rehearse sexual acts and inspect one another’s genitals. On some occasions, Money would even photograph the twins doing these exercises. Money claimed that childhood sexual rehearsal play was important for healthy childhood sexual exploration.

David also recalls receiving anger and verbal abuse from Money if they resisted participation.

Money (1972) reported on Reimer’s progress as the “John/Joan case” to keep the identity of David anonymous. Money described David’s transition as successful.

He claimed that David behaved like a little girl and did not demonstrate any of the boyish mannerisms of his twin brother Brian. Money would publish this data to reinforce his theories on gender fluidity and to justify that gender identity is primarily learned.

In reality, though, David was never happy as a girl. He rejected his female identity and experienced severe gender dysphoria . He would complain to his parents and teachers that he felt like a boy and would refuse to wear dresses or play with dolls.

He was severely bullied in school and experienced suicidal depression throughout adolescence. Upon learning about the truth about his birth and sex of rearing from his father at the age of 15, David assumed a male gender identity, calling himself David.

David Reimer underwent treatments to reverse the assignment such as testosterone injections and surgeries to remove his breasts and reconstruct a penis.

David married a woman named Jane at 22 years and adopted three children.

Dr. Milton Diamond, a psychologist and sexologist at the University of Hawaii and a longtime academic rival of John Money, met with David to discuss his story in the mid-1990s.

Diamond (1997) brought David’s experiences to international attention by reporting the true outcome of David’s case to prevent physicians from making similar decisions when treating other infants. Diamond helped debunk Money’s theory that gender identity could be completely learned through intervention.

David continued to suffer from psychological trauma throughout adulthood due to Money’s experiments and his harrowing childhood experiences. David endured unemployment, the death of his twin brother Brian, and marital difficulties.

At the age of thirty-eight, David committed suicide.

David’s case became the subject of multiple books, magazine articles, and documentaries. He brought to attention to the complications of gender identity and called into question the ethicality of sex reassignment of infants and children.

Originally, Money’s view of gender malleability dominated the field as his initial report on David was that the reassignment had been a success. However, this view was disproved once the truth about David came to light.

His case led to a decline in the number of sex reassignment surgeries for unambiguous XY male infants with a micropenis and other congenital malformations and brought into question the malleability of gender and sex.

At present, however, the clinical literature is still deeply divided on the best way to manage cases of intersex infants.

Colapinto, J. (2000). As nature made him: The boy who was raised as a girl. New York, NY: Harper Collins.

Colapinto, J. (2018). As nature made him: The boy who was raised as a girl. Langara College.

Diamond, M., & Sigmundson, H. K. (1997). Sex reassignment at birth: Long-term review and clinical implications . Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine, 151(3), 298-304.

Money, J., & Ehrhardt, A. A. (1972). Man & Woman, Boy & Girl : The Differentiation and Dimorphism of Gender Identity from Conception to Maturity. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Money, J., & Tucker, P. (1975). Sexual signatures: On being a man or a woman.

Money, J. (1994). The concept of gender identity disorder in childhood and adolescence after 39 years . Journal of sex & marital therapy, 20(3), 163-177.

David Reimer and John Money Gender Reassignment Controversy: The John/Joan Case

In the mid-1960s, psychologist John Money encouraged the gender reassignment of David Reimer, who was born a biological male but suffered irreparable damage to his penis as an infant. Born in 1965 as Bruce Reimer, his penis was irreparably damaged during infancy due to a failed circumcision. After encouragement from Money, Reimer’s parents decided to raise Reimer as a girl. Reimer underwent surgery as an infant to construct rudimentary female genitals, and was given female hormones during puberty. During childhood, Reimer was never told he was biologically male and regularly visited Money, who tracked the progress of his gender reassignment. Reimer unknowingly acted as an experimental subject in Money’s controversial investigation, which he called the John/Joan case. The case provided results that were used to justify thousands of sex reassignment surgeries for cases of children with reproductive abnormalities. Despite his upbringing, Reimer rejected the female identity as a young teenager and began living as a male. He suffered severe depression throughout his life, which culminated in his suicide at thirty-eight years old. Reimer, and his public statements about the trauma of his transition, brought attention to gender identity and called into question the sex reassignment of infants and children.

Bruce Peter Reimer was born on 22 August 1965 in Winnipeg, Ontario, to Janet and Ron Reimer. At six months of age, both Reimer and his identical twin, Brian, were diagnosed with phimosis, a condition in which the foreskin of the penis cannot retract, inhibiting regular urination. On 27 April 1966, Reimer underwent circumcision, a common procedure in which a physician surgically removes the foreskin of the penis. Usually, physicians performing circumcisions use a scalpel or other sharp instrument to remove foreskin. However, Reimer’s physician used the unconventional technique of cauterization, or burning to cause tissue death. Reimer’s circumcision failed. Reimer’s brother did not undergo circumcision and his phimosis healed naturally. While the true extent of Reimer’s penile damage was unclear, the overwhelming majority of biographers and journalists maintained that it was either totally severed or otherwise damaged beyond the possibility of function.

In 1967, Reimer’s parents sought the help of John Money, a psychologist and sexologist who worked at the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland. In the mid-twentieth century, Money helped establish views on the psychology of gender identities and roles. In his academic work, Money argued in favor of the increasingly mainstream idea that gender was a societal construct, malleable from an early age. He stated that being raised as a female was in Reimer’s interest, and recommended sexual reassignment surgery. At the time, infants born with abnormal or intersex genitalia commonly received such interventions.

Following their consultation with Money, Reimer’s parents decided to raise Reimer as a girl. Physicians at the Johns Hopkins Hospital removed Reimer’s testes and damaged penis, and constructed vestigial vulvae and a vaginal canal in their place. The physicians also opened a small hole in Reimer’s lower abdomen for urination. Following his gender reassignment surgery, Reimer was given the first name Brenda, and his parents raised him as a girl. He received estrogen during adolescence to promote the development of breasts. Throughout his childhood, Reimer was not informed about his male biology.

Throughout his childhood, Reimer received annual checkups from Money. His twin brother was also part of Money’s research on sexual development and gender in children. As identical twins growing up in the same family, the Reimer brothers were what Money considered ideal case subjects for a psychology study on gender. Reimer was the first documented case of sex reassignment of a child born developmentally normal, while Reimer’s brother was a control subject who shared Reimer’s genetic makeup, intrauterine space, and household.

During the twin’s psychiatric visits with Money, and as part of his research, Reimer and his twin brother were directed to inspect one another’s genitals and engage in behavior resembling sexual intercourse. Reimer claimed that much of Money’s treatment involved the forced reenactment of sexual positions and motions with his brother. In some exercises, the brothers rehearsed missionary positions with thrusting motions, which Money justified as the rehearsal of healthy childhood sexual exploration. In a Rolling Stone interview, Reimer recalled that at least once, Money photographed those exercises. Money also made the brothers inspect one another’s pubic areas. Reimer stated that Money observed those exercises both alone and with as many as six colleagues. Reimer recounted anger and verbal abuse from Money if he or his brother resisted orders, in contrast to the calm and scientific demeanor Money presented to their parents. Reimer and his brother underwent Money’s treatments at preschool and grade school age. Money described Reimer’s transition as successful, and claimed that Reimer’s girlish behavior stood in stark contrast to his brother’s boyishness. Money reported on Reimer’s case as the John/Joan case, leaving out Reimer’s real name. For over a decade, Reimer and his brother unknowingly provided data that, according to biographers and the Intersex Society of North America, was used to reinforce Money’s theories on gender fluidity and provided justification for thousands of sex reassignment surgeries for children with abnormal genitals.

Contrary to Money’s notes, Reimer reports that as a child he experienced severe gender dysphoria, a condition in which someone experiences distress as a result of their assigned gender. Reimer reported that he did not identify as a girl and resented Money’s visits for treatment. At the age of thirteen, Reimer threatened to commit suicide if his parents took him to Money on the next annual visit. Bullied by peers in school for his masculine traits, Reimer claimed that despite receiving female hormones, wearing dresses, and having his interests directed toward typically female norms, he always felt that he was a boy. In 1980, at the age of fifteen, Reimer’s father told him the truth about his birth and the subsequent procedures. Following that revelation, Reimer assumed a male identity, taking the first name David. By age twenty-one, Reimer had received testosterone therapy and surgeries to remove his breasts and reconstruct a penis. He married Jane Fontaine, a single mother of three, on 22 September 1990.

In adulthood, Reimer reported that he suffered psychological trauma due to Money’s experiments, which Money had used to justify sexual reassignment surgery for children with intersex or damaged genitals since the 1970s. In the mid-1990s, Reimer met Milton Diamond, a psychologist at the University of Hawaii, in Honolulu, Hawaii, and an academic rival of Money. Reimer participated in a follow-up study conducted by Diamond, in which Diamond cataloged the failures of Reimer’s transition.

In 1997, Reimer began speaking publicly about his experiences, beginning with his participation in Diamond’s study. Reimer’s first interview appeared in the December 1997 issue of Rolling Stone magazine. In interviews, and a later book about his experience, Reimer described his interactions with Money as torturous and abusive. Accordingly, Reimer claimed he developed a lifelong distrust of hospitals and medical professionals.

With those reports, Reimer caused a multifaceted controversy over Money’s methods, honesty in data reporting, and the general ethics of sex reassignment surgeries on infants and children. Reimer’s description of his childhood conflicted with the scientific consensus about sex reassignment at the time. According to NOVA , Money led scientists to believe that the John/Joan case demonstrated an unreservedly successful sex transition. Reimer’s parents later blamed Money’s methods and alleged surreptitiousness for the psychological illnesses of their sons, although the notes of a former graduate student in Money’s lab indicated that Reimer’s parents dishonestly represented the transition’s success to Money and his coworkers. Reimer was further alleged by supporters of Money to have incorrectly recalled the details of his treatment. On Reimer’s case, Money publicly dismissed his criticism as anti-feminist and anti-trans bias, but, according to his colleagues, was personally ashamed of the failure.

In his early twenties, Reimer attempted to commit suicide twice. According to Reimer, his adult family life was strained by marital problems and employment difficulty. Reimer’s brother, who suffered from depression and schizophrenia, died from an antidepressant drug overdose in July of 2002. On 2 May 2004, Reimer’s wife told him that she wanted a divorce. Two days later, at the age of thirty-eight, Reimer committed suicide by firearm.

Reimer, Money, and the case became subjects of numerous books and documentaries following the exposé. Reimer also became somewhat iconic in popular culture, being directly referenced or alluded to in the television shows Chicago Hope , Law & Order , and Mental . The BBC series Horizon covered his story in two episodes, “The Boy Who Was Turned into a Girl” (2000) and “Dr. Money and the Boy with No Penis” (2004). Canadian rock group The Weakerthans wrote “Hymn of the Medical Oddity” about Reimer, and the New York-based Ensemble Studio Theatre production Boy was based on Reimer’s life.

- Carey, Benedict. “John William Money, 84, Sexual Identity Researcher, Dies.” New York Times , 11 July 2006.

- Colapinto, John. "The True Story of John/Joan." Rolling Stone 11 (1997): 54–73.

- Colapinto, John. As Nature Made Him: The Boy who was Raised as a Girl . New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2000.

- Colapinto, John. "Gender Gap—What were the real reasons behind David Reimer’s suicide?" Slate (2004).

- Dr. Money and the Boy with No Penis , documentary, written by Sanjida O’Connell (BBC, 2004), Film.

- The Boy Who Was Turned Into a Girl , documentary, directed by Andrew Cohen (BBC, 2000.), Film.

- “Who was David Reimer (also, sadly, known as John/Joan)?” Intersex Society of North America . http://www.isna.org/faq/reimer (Accessed October 31, 2017).

How to cite

Articles rights and graphics.

Copyright Arizona Board of Regents Licensed as Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0)

Last modified

Share this page.

David Reimer And The Tragic Story Of The ‘John/Joan Case’

David reimer was born a boy in winnipeg, canada in 1965 — but following a botched circumcision at the age of eight months, his parents raised him as a girl..

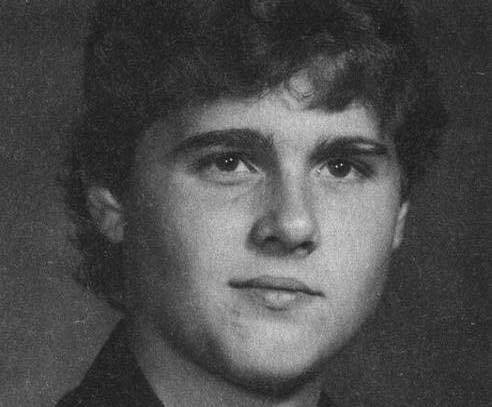

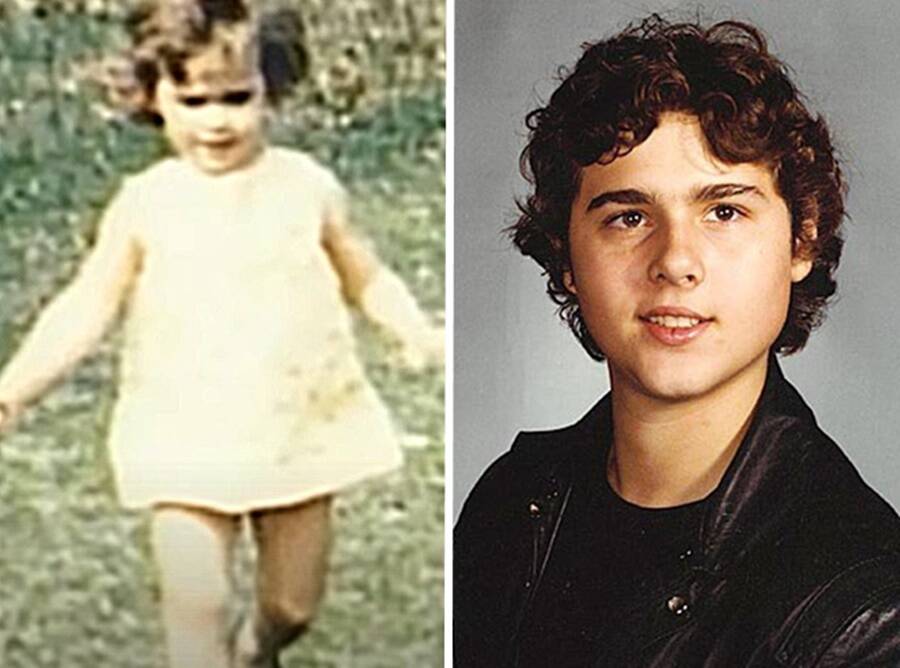

Facebook Although David Reimer’s story was initially seen as a success by his family and Dr. John Money, his story would eventually prove to have a tragic end.

David Reimer’s parents just wanted to do the right thing for him.

What was supposed to be a routine circumcision in 1965 turned into a life-altering nightmare for the Reimer family when the doctor performing his surgery accidentally singed the infant’s penis.

The damage was irreparable. Concerned that their son’s injury might cause him mental anguish as an adult, Reimer’s parents consulted with famed sexologist Dr. John Money after seeing him on television.

Money consequently suggested that Reimer undergo sex reassignment surgery and instead be raised female. Desperate, Reimer’s parents took his advice and changed their son’s name from “Bruce” to “Brenda.”

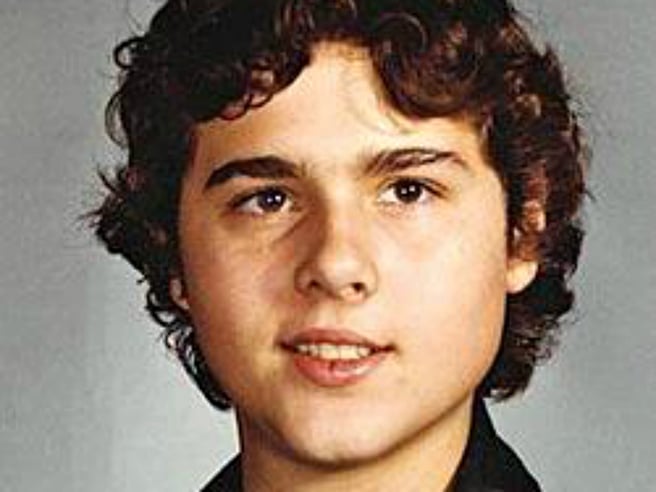

YouTube/Facebook David Reimer, born Bruce Reimer and biologically male, began an imposed gender transition as an infant.

Reimer appeared to take easily to his imposed gender identity as a female, and his case was initially seen as a success story by those physicians like Money who believed that gender was a matter of learned or taught behavior and not nature.

But in reality, Reimer struggled even as a child with his gender identity. Once he discovered the truth about his birth as a teenager, Reimer began a painful journey to return to his biological sex.

However, he could never fully recover. Finally, in 2004, David Reimer took his own life at the age of just 38.

David Reimer’s Future Is Decided By Sexologist John Money

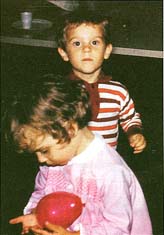

In Memory of David Reimer/Facebook At 14, David Reimer (right) chose to live as a male.

David Reimer was born Bruce Reimer in Winnipeg, Canada, in 1965. He had a twin brother named Brian, and the two were the first children of a rural teenage couple, Janet and Ron.

The baby boys were healthy but, at about eight months old, showed signs of difficulty with urinating. They were diagnosed with phimosis, a condition in which the foreskin cannot retract.

The Reimers took their children to be circumcised at the hospital, but after Bruce Reimer’s surgery went horribly awry because the surgeon used an electrocautery needle instead of a blade, Brian was not subjected to the same surgery and his phimosis healed naturally.

David Reimer’s parents desperately sought solutions for him until they saw psychologist John Money speak about his work on TV.

Money was considered one of the top sex researchers in the United States, and he specialized in the experiences of intersex children who, according to the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, “do not fit the typical definitions for male or female bodies.”

Reimer’s mother wrote to Money explaining the horrible accident her son had endured. Within a few weeks, the young parents were on their way to see the doctor at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland.

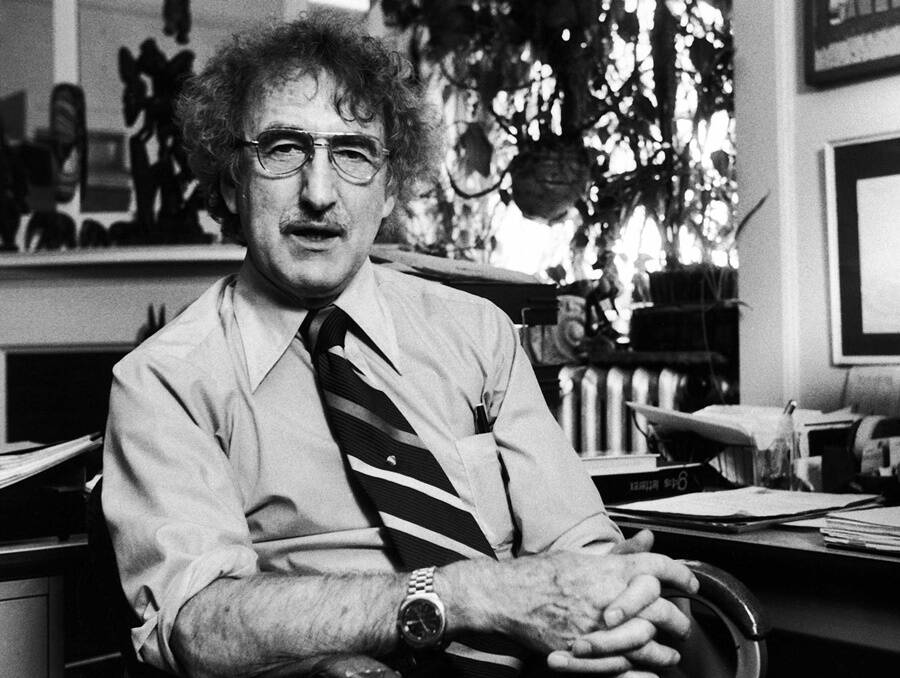

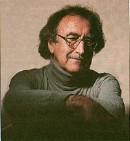

Diana Walker/The LIFE Images Collection via Getty Images Psychologist John Money claimed his gender experiment on the Reimer twins was a success — despite early warning signs that proved otherwise.

Money believed that a person’s gender identity was a social construct and the result of their upbringing. As such, he proposed that someone could be “taught” to identify differently than their biological sex.

Money thought that children were “gender-neutral” until about the age of two and theorized that parents had a period of time that he called the “gender gate” during which they could influence the sex of their child behaviorally.

The doctor thus made the radical proposition to reassign Bruce Reimer’s gender surgically, which would involve castrating his penis and giving him a prosthetic vagina instead. He would then be raised as a girl and not told of his former identity. Reimer’s parents agreed to the procedure and the infant’s imposed transition began shortly before his second birthday in 1967.

To Money, this situation also provided him with an opportunity to investigate his theory about gender identity. But his medical advice would prove fatally wrong in the case of David Reimer.

Reimer’s Troubled Childhood And The Eventual Reveal Of The Truth

In Memory of David Reimer/Facebook Despite his tumultuous life, David Reimer found love with his wife Jane.

Upon John Money’s recommendation, Bruce Reimer began life as Brenda Reimer.

In addition to his sex reassignment surgery, Reimer was given estrogen supplements to help “feminize” his body. The Reimers returned to Money’s office every year so that the doctor could monitor both Brian and Brenda’s growth as a boy and a girl. The radical study became known as the John/Joan case.

Money noted that the twin sister, a.k.a. Brenda, was “much neater” than her twin brother Brian. Money also noted that Brenda was the more stubborn and dominant personality, which he dismissed as “tomboy traits.”

In 1975, when the twins turned nine, Money published his study in a book called Sexual Signatures where he described Reimer’s forced transition to Brenda as a success:

“The girl already preferred dresses to pants enjoyed wearing her hair ribbons, bracelets, and frilly blouses, and loved being her daddy’s little sweetheart. Throughout childhood, her stubbornness and the abundant physical energy she shares with her twin brother and expends freely have made her a tomboyish girl, but nonetheless a girl.”

But nothing could be further from the truth. Indeed, Reimer recalled his childhood as far more distressing.

“I never quite fit in,” David Reimer said in a 2000 interview on Oprah . “Building forts and getting into the odd fistfight, climbing trees — that’s the kind of stuff that I liked, but it was unacceptable as a girl.”

According to author John Colapinto who worked with Reimer on his book As Nature Made Him: The Boy Who Was Raised as A Girl , the frequent visits Reimer made to Money’s office were also traumatic.

Reimer was shown pictures of naked adults to “reinforce Brenda’s gender identity” and pressed by Money to endure more surgeries that would make him more feminine. Both of the twins would later accuse Money of making them pose in various sexual positions which, according to Money, was just another element of his theory that involved “sexual rehearsal play.”

Janet Reimer reportedly wasn’t blind to her child’s discomfort with his female gender identity, either. She recalled the first time that Reimer was put in a dress he angrily tore it off. “There were doubts along the way,” Janet confessed on Oprah . “But I couldn’t afford to contemplate them because I couldn’t afford to be wrong.”

Problems at home extended to school. Reimer was teased by classmates for his “masculine gait” and his standing to pee in the girl’s bathroom. When Reimer complained about feeling like a boy, his parents and other adults convinced him that it was just a phase.

Reimer’s secret disrupted the family. His father sunk into alcoholism and his mother attempted suicide. Reimer’s twin sibling, Brian, later descended into substance abuse and petty crime.

It wasn’t until the twins entered their teens that other doctors convinced the Reimers that it was time to tell their children the truth. After picking up Brenda from a psychologist appointment in 1980, Ron Reimer drove both his children to an ice cream parlor where he told them the whole story.

“Suddenly it all made sense why I felt the way I did,” Reimer said of the revelation. “I wasn’t some sort of weirdo. I wasn’t crazy.”

The Tragic End Of David Reimer’s Story

After discovering the truth, Reimer chose to live as a boy and assumed the name “David.”

He endured multiple surgeries to restore his gender to male, including a double mastectomy to remove the breasts that had grown from years of estrogen therapy and attaching an artificial penis in place of his artificial vagina. He also took testosterone supplements.

But the physical stress wore on his mental health. By his early 20s, Reimer had attempted suicide twice and remained deeply depressed for years after.

Despite his anguish, however, Reimer found love and married a woman named Jane. They were together for 14 years. He was a stepfather to her three children and developed hobbies like camping, fishing, antiques, and collecting old coins.

In Memory of David Reimer/Facebook David Reimer took his own life in May 2004. He was 38.

Reimer later agreed to work with a second sexologist named Milton Diamond on the expectation that speaking about his experience might prevent physicians from making similar decisions for other infants.

Diamond criticized Money’s study for its lack of evidence and worked with Reimer to debunk Money’s theory that gender identity could be totally taught or learned. In 1997, around the time Reimer began speaking publicly about his childhood ordeal, Diamond’s study was published in Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine .

The breakthrough paper laid the foundation against performing sex reassignment surgery on intersex infants, which was once considered a “fix” for their gender non-conforming biology.

But the validation of the study wasn’t enough for Reimer to overcome his traumatic childhood. In May 2004, two years after his twin brother succumbed to a drug overdose, David Reimer killed himself. He was 38.

Reimer’s case was complex. His first gender transition was based on a medical accident and a scientific theory. As a result, he experienced gender dysphoria, which is the feeling that one’s biological sex differs from their gender identity. People who identify as transgender often experience gender dysphoria early in life as well.

Reimer may no longer be alive, but his journey to reclaim his gender identity contributed to a better understanding of the relationship between gender and biological sex.

After this look at the story of David Reimer, meet Maryam Khatoon Molkara , the transgender Iranian activist who helped legalize gender-confirming surgeries in Iran. Then, learn about Christine Jorgensen , America’s original transgender celebrity.

PO Box 24091 Brooklyn, NY 11202-4091

- Women / transfeminine

- Men / transmasculine

- Gender diverse / nonbinary +

- For gender questioning people

- For allies & supporters

- For everyone else

- For young visitors

- For parents

- For educators

- For healthcare providers

- Military service

- Public accommodation

- Youth issues

John Money vs. sex and gender minorities

John Money (1921–2006) was a New Zealand psychologist and sex researcher known for many ethical controversies:

the Reimer twins scandal (the “John/Joan case”)

- ordering surgical sex reassignment on 22-month-old infant David Reimer (1967)

- posing the Reimer twins in simulated sex acts and photographing it

- falsifying and covering up the outcome of the case

- contributing to the adult suicides of both brothers (Brian in 2002, David in 2004)

exploiting people with differences of sex development

- Hermaphroditism: An Inquiry into the Nature of a Human Paradox (1952)

coining or popularizing numerous terms and concepts:

- gender role (1955)

- gender identity (orginally proposed by Robert Stoller in 1964)

- sexual orientation

- amative orientation (2002)

- paraphilia (Krauss 1903; Robinson 1913; Stekel 1930)

- vandalized lovemaps (1989)

- gendermaps (1995)

- bodymind (1988)

outlining variables of sex (1955):

- assigned sex and sex of rearing

- external genital morphology

- internal reproductive structures

- hormonal and secondary sex characteristics

- gonadal sex

- chromosomal sex

- gender role and orientation as male or female, established while growing up

making biased claims about trans women:

- Transsexualism and Sex Reassignment (1969)

- “devious, demanding and manipulative” and incapable of love (1970)

John Money should have died in prison along with other “leading lights” of late 20th-century sexology. The astonishing lack of accountability or responsibility makes him easily the most unethical sexologist in history.

John Money vs. J. Michael Bailey

Takes one to know one, they say.

John Money was an ethically-challenged sexologist at Johns Hopkins whose work led to the woes of untold intersex people around the world until his “science” was debunked and his academic misconduct exposed.

Mike Bailey is an ethically-challenged sexologist at Northwestern whose work nearly led to the woes of untold transgender people around the world until his “science” was debunked and his academic misconduct exposed.

John Money put out a book in May 1990 with the title:

Gay, Straight, and In-Between

Mike Bailey’s publicist did an article in March 2003 titled:

Gay, Straight or Lying? Science has the answer [1]

The similarities in titles certainly beg a comparison, as do the remarkable similarities in the lives of the two well-known sexologists.

Why would Bailey and friends replace “in-between” with “lying”? Below is a very interesting passage from pages 108-110 of John Money’s Gay, Straight, and In-Between: The Sexology of Exotic Orientation .

“Gender Crosscoding”

by John Money

Among adolescents who circumvent homosexual activity or who quit in panic, there are some who coerce themselves into heterosexuality, only to find as husbands and fathers (or wives and mothers, in the case of females) that the lid on Pandora’s box springs open. These are the people who, when young adulthood advances into midlife, begin the homosexual stage of sequential bisexuality. For some the transition is to homosexual relations exclusively, whereas for others heterosexual relations also may continue. The transition may take place autonomously, or it may be a sequel to the divorce or death of the spouse or to sexual apathy in the marriage. When the youngest child leaves home, there may be a degree of freedom hitherto unavailable. The bisexualism of a parent is not transmitted to the offspring, and is not contagious. However, to avoid offending a heterosexual child, a bisexual parent may be self-coerced into suppressing homosexual expression.

The late expression of homosexuality in sequential bisexuality may be associated with recovery from illness and debilitation (e.g., recovery from alcoholism) that had masked the homosexual potential. Hypothetically, it might, conversely, be associated with premature illness and deterioration from brain injury or disease, as in temporal lobe trauma and Alzheimer’s disease. However, although brain pathology may release the expression of sexuality formerly strictly self-prohibited as indecent or immoral, it is not especially associated with releasing bisexuality.

In sequential bisexuality, the transition from homosexual to heterosexual expression is also known to occur autonomously in adulthood. Since this transition is socially approved and not registered as pathological, it is not likely to be recorded. If the individual were at the time in some type of treatment, the transition might be wrongly construed as a therapeutic triumph.

More than sequential bisexuality, concurrent bisexuality may be jocularly considered as having the best of two possible worlds. But it has a dark and sinister potential also. Its most malignant expression is in those individuals in whom it takes the form of a Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. The split applies not simply to heterosexuality and homosexuality, but to good and evil, licit and illicit, as well. The two names are not gender-coded as male and female as they are in the two names of the tranvsvestophile, nor are the two personalities and the two wardrobes. Instead, the two names, wardrobes, and personalities are both male (or in the less likely case of women, female), but one, the given name with its wardrobe and personality, is for the heterosexual, and the other, an alias or a nickname, for the homosexual. The heterosexual personality is the servant of righteousness and the acolyte of a vengeful God. The homosexual personality is the servant of transgression and a fallen angel in the legions of Lucifer. The heterosexual personality has the pontificating mission of a sadistic grand inquisitor, bent on the exorcism of those possessed of homosexuality, himself included. The homosexual personality has the absolving mission of officiating indulgences in the place of masochistic penances for homosexuality, but only for himself and nobody else.

The absolute antithesis of homophobia and homophilia in this malignant form of bisexuality takes its toll in self-sabotage and the sabotage of others. Self-sabotage is an ever-present threat that materializes if there is a leakage of information from those in one antithetical world to those in the other. The greater danger is, of course, that knowledge of the illicit homosexual existence will leak out to the society that knows only of the heterosexual existence. The ensuing societal abuse and deprivation, legal and social, may be extreme.

The sabotage of others is carried out professionally by some individuals with the syndrome of malignant bisexualism. Their internal homophobic war against their own homosexuality becomes externalized into a war against homosexuality in others. The malignant bisexual becomes a secret agent, living in his own private and secret homosexual world, while spying on its inhabitants, entrapping them, assaulting and killing them, or, with less overt violence, preaching against them, legislating against them, or judicially depriving them of the right to exist.

The malignant bisexual is the perfect recruit for the position of homosexual entrapment officer or decoy in the employ of the police vice squad. Supported by clandestine operations, blackmail, and threats of exposure, in espionage or in the secret police of government surveillance, he may achieve legendary power, such as that attributed to J. Edgar Hoover of mythical FBI fame.

People in high places may have the power to keep under cover for a lifetime, with the homosexual manifestations of their bisexuality never exposed. Others have their career blown, as did the bisexual former U.S. congressman from Maryland, Robert E. Bauman, a fanatical homophobic ultraconservative of the religious new right, who subsequently published a biography of his own downfall (Bauman 1986).

Bauman was exposed by a combination of surveillance and the testimony of a paid informant and blackmailer. Nowadays there is a hitherto nonexistent way of being suspected or exposed, namely by dying of AIDS. This is what happened to Roy Cohn (New York Times, August 3, 1986), the malignantly bisexual legal counsel for the homosexual witch hunter from Wisconsin, U.S. Senator Joseph McCarthy, himself suspected of malignant bisexuality. Together, they destroyed the lives of many American citizens, simply by publicly accusing them of being homosexual, falsely or otherwise.

Scratch the surface of the self-righteous and find the devil. This is a maxim of widespread acceptability, not only to the self-righteous in high places of homophobic power, influence, and authority, but also to the homophobic, gay-bashing hoodlums who, as in the case with which this section began, pick up or are picked up by a gay man, have sex with him, and then exorcise their own homosexual guilt by assaulting and maybe killing him. Both versions of homophobia are manifestations of malignant bisexuality that, in an interview with the journalist, Doug Ireland, for New York Magazine (July 24, 1978), I called the exorcist syndrome.

There must be a very widespread prevalence of lesser degrees of the exorcist syndrome in the population at large. If it were not so, otherwise-decent people would not persecute their homosexual fellow citizens nor tolerate their persecution. Instead they would live and let live those who are destined to have a different way of being human in love and sex. They would tolerate them as they do the left-handed. Tolerance would remove those very pressures that progressively coerce increasing numbers of our children and grandchildren to grow up blighted with the curse of malignant bisexuality.

1. Pinnel , Robin (March 21, 2003). Gay, straight, or lying? Science has the answer. Joseph Henry Press

Bullough, Vern L. “The contributions of John Money: a personal view.” The Journal of Sex Research , vol. 40, no. 3, 2003, pp. 230–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490309552186

John Money and John G. Brennan, “Heterosexual vs. homosexual attitudes: male partners’ perception of the feminine image of male transsexuals,” The Journal of Sex Research , 6, 3 (1970): 193–209, 201, 202. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224497009550666

John Money, John L. Hampson, Joan G. Hampson. Hermaphroditism: Psychology & Case Management April 1, 1960 https://doi.org/10.1177/070674376000500214

Ehrhardt, Anke A. ‘John Money, PhD’ Journal of Sex Research 44.3 (2007): 223–224.

Downing, Lisa; Morland, Iain; Sullivan, Nikki (26 November 2014). Fuckology: Critical Essays on John Money’s Diagnostic Concepts . Chicago, Illinois : University of Chicago Press .

Goldie, Terry (2014). The Man Who Invented Gender: Engaging the Ideas of John Money . Vancouver, British Columbia: University of British Columbia Press.

Tosh, Jemma (25 July 2014). Perverse Psychology: The pathologization of sexual violence and transgenderism . Routledge. ISBN 9781317635444.

Diamond, M; Sigmundson, HK (1997). “Sex reassignment at birth. Long-term review and clinical implications” . Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine . 151 (3): 298–304. doi : 10.1001/archpedi.1997.02170400084015

John William Money, PhD, 1921–2006

https://web.archive.org/web/20150724204551/http://www.sexualhealth.umn.edu/education/john-money/bio

Brewington, Kelly (9 July 2006). “Dr. John Money 1921–2006: Hopkins pioneer in gender identity” . Baltimore Sun . http://articles.baltimoresun.com/2006-07-09/news/0607090031_1_gender-johns-hopkins-john-money

Money, John; Hampson, Joan G; Hampson, John (October 1955). “An Examination of Some Basic Sexual Concepts: The Evidence of Human Hermaphroditism”. Bull. Johns Hopkins Hosp . Johns Hopkins University. 97 (4): 301–19. PMID 13260820.

Colapinto, John (11 December 1997). “The True Story of John/Joan” . Rolling Stone : 54–97. Archived from the original on 15 August 2000. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

“David Reimer, 38, Subject of the John/Joan Case” . The New York Times . 12 May 2004. Retrieved 27 September 2014. https://www.nytimes.com/2004/05/12/us/david-reimer-38-subject-of-the-john-joan-case.html

Carey, Benedict (11 July 2006). John William Money, 84, Sexual Identity Researcher, Dies , The New York Times https://www.nytimes.com/2006/07/11/us/11money.html

John Money, Ph.D. Kinsey Institute https://kinseyinstitute.org/collections/archival/john-money.php

Man and woman, boy and girl: Differentiation and dimorphism of gender identity from conception to maturity.

J Money, AA Ehrhardt – 1972

Imprinting and the establishment of gender role

J Money, JG Hampson… – AMA Archives of Neurology …, 1957

Sexual signatures: On being a man or a woman.

J Money, P Tucker – 1975 –

Gay, straight, and in-between: The sexology of erotic orientation

J Money – 1988 –

Lovemaps: Clinical concepts of sexual/erotic health and pathology, paraphilia, and gender transposition in childhood, adolescence, and maturity

J Money – 2012

Complete androgen insensitivity syndrome: long-term medical, surgical, and psychosexual outcome

…, GD Berkovitz, TR Brown, J Money – The Journal of …, 2000 –

Ablatio penis: normal male infant sex-reassigned as a girl

J Money – Archives of sexual behavior, 1975 –

The concept of gender identity disorder in childhood and adolescence after 39 years

J Money – Journal of sex & marital therapy, 1994 –

Ambiguous genitalia with perineoscrotal hypospadias in 46, XY individuals: long-term medical, surgical, and psychosexual outcome

…, TR Brown, SJ Casella , A Maret, KM Ngai, J Money … – Pediatrics, 2002

Adult erotosexual status and fetal hormonal masculinization and demasculinization: 46, XX congenital virilizing adrenal hyperplasia and 46, XY androgen-insensitivity …

J Money , M Schwartz, VG Lewis – Psychoneuroendocrinology, 1984 –

Apotemnophilia: two cases of self‐demand amputation as a paraphilia

J Money , R Jobaris, G Furth – Journal of Sex Research, 1977

Paraphilias: Phenomenology and classification

J Money – American journal of psychotherapy, 1984

Gender role, gender identity, core gender identity: Usage and definition of terms

J Money – Journal of the American Academy of Psychoanalysis, 1973

Forensic sexology: Paraphilic serial rape (biastophilia) and lust murder (erotophonophilia)

J Money – American Journal of Psychotherapy, 1990

Progestin‐induced hermaphroditism: IQ and psychosexual identity in a study of ten girls∗

AA Ehrhardt, J Money – Journal of Sex Research, 1967 –

Sin, sickness, or status? Homosexual gender identity and psychoneuroendocrinology.

J Money – American Psychologist, 1987 –

Sex errors of the body: Dilemmas, education, counseling.

J Money – 1968 – psycnet.apa.org

Homosexual outcome of discordant gender identity/role in childhood: Longitudinal follow-up

J Money, AJ Russo – Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 1979

Gendermaps: Social constructionism, feminism and sexosophical history

J Money – 2016

Sex errors of the body and related syndromes: A guide to counseling children, adolescents, and their families

J Money – 1994 –

Gender: history, theory and usage of the term in sexology and its relationship to nature/nurture

J Money – Journal of sex & marital therapy, 1985

Use of an androgen‐depleting hormone in the treatment of male sex offenders

J Money – Journal of Sex Research, 1970 –

Vandalized lovemaps: Paraphilic outcome of seven cases in pediatric sexology.

J Money, M Lamacz – 1989 –

Sex research: New developments.

JE Money – 1965

46, XY intersex individuals: phenotypic and etiologic classification, knowledge of condition, and satisfaction with knowledge in adulthood

…, JA Rock , HFL Meyer-Bahlburg, J Money… – Pediatrics, 2002

Incongruous gender role: nongenital manifestations in prepubertal boys.

R Green, J Money – Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 1960 –

Fetal feminization and female gender identity in the testicular feminizing syndrome of androgen insensitivity

DN Masica, J Money, AA Ehrhardt – Archives of Sexual Behavior, 1971

Sexual dimorphism and homosexual gender identity.

J Money – Psychological Bulletin, 1970 –

Iatrogenic homosexuality: Gender identity in seven 46, XX chromosomal females with hyperadrenocortical hermaphroditism born with a penis, three reared as boys …

J Money, J Dalery – Journal of Homosexuality, 1976

Effeminacy in prepubertal boys: Summary of eleven cases and recommendations for case management

R Green, J Money – Pediatrics, 1961 –

Hermaphrodism: recommendations concerning case management

JG Hampson, J Money… – The Journal of Clinical …, 1956 –

Sexual dimorphism and dissociation in the psychology of male transsexuals.

J Money, C Primrose – Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 1968 –

Gynemimesis and gynemimetophilia: Individual and cross-cultural manifestations of a gender-coping strategy hitherto unnamed

J Money, M Lamacz – Comprehensive psychiatry, 1984

Genital examination and exposure experienced as nosocomial sexual abuse in childhood.

J Money, M Lamacz – Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 1987

Stage-acting, role-taking, and effeminate impersonation during boyhood

R Green, J Money – Archives of General Psychiatry, 1966

The True Story of John / Joan

J o h n / joan.

By John Colapinto The Rolling Stone, December 11, 1997. Pages 54-97

In 1967, an anonymous baby boy was turned into a girl by doctors at Johns Hopkins Hospital. For 25 years, the case of John/Joan was called a medical triumph — proof that a child's gender identity could be changed — and thousands of "sex reassignments" were performed based on this example. But the case was a failure, the truth never reported. Now the man who grew up as a girl tells the story of his life, and a medical controversy erupts.

In late June 1997, I arrive at an address in a working-class suburb in the North American Midwest. On the front lawn, a child's bicycle lies on its side; an eight-year-old secondhand Toyota is parked at the curb. Inside the house, a handmade wooden cabinet in the corner of the living room holds the standard emblems of family life: wedding photos and school portraits, china figurines and souvenirs from family trips. There is a knockoff-antique coffee table, a well-worn easy chair and a sofa - which is where my host, a wiry young man dressed in a jean jacket and scuffed work boots, seats himself. He is 31 years old but could pass for a decade younger. Partly it's the sparseness of his beard - just a few blond wisps that sprout from his jaw line; partly it's a certain delicacy to his prominent cheekbones and tapering chin. Otherwise he looks, and sounds, exactly like what he is: a blue-collar factory worker, a man of high school education whose fondest pleasures are to do a little weekend fishing with his dad in the local river and to have a backyard barbecue with his wife and kids.Ordinarily a rough-edged and affable young man, he stops smiling when conversation turns to his childhood. Then his voice - a burred baritone - takes on a tone of aggrievement and anger, or the pleading edge of someone desperate to communicate emotions that he knows his listener can only dimly understand. How well even he understands these emotions is not clear: When describing events that occurred prior to his 15th birthday, he tends to drop the pronoun I from his speech, replacing it with the distancing you - almost as if he were speaking about someone else altogether. Which, in a sense, he is.

"It was like brainwashing," he is saying now as he lights a cigarette. "I'd give just about anything to go to a hypnotist to black out my whole past. Because it's torture. What they did to you in the body is sometimes not near as bad as what they did to you in the mind - with the psychological warfare in your head."

It's a fame that derives not only from the fact that his medical metamorphosis was the first sex reassignment ever reported on a developmentally normal child but also from a stunning statistical long shot that lent a special significance to the case. He was born an identical twin, and his brother provided the experiment with a built-in matched control - a genetic clone who, with penis intact, was raised as a male. That the twins were reported to have grown into happy, well-adjusted children of opposite sex seemed unassailable proof of the primacy of rearing over biology in the differentiation of the sexes and was the basis for the rewriting of textbooks in a wide range of medical disciplines. Most seriously, the case set a precedent for sex reassignment as the standard treatment for thousands of newborns with similarly injured, or irregular, genitals. It also became a touchstone for the feminist movement in the 1970s, when it was cited as living proof that the gender gap is purely a result of cultural conditioning, not biology. For Dr. John Money, the medical psychologist who was the architect of the experiment, this case was to be the most publicly celebrated triumph of a 40-year career that recently earned him the accolade "one of the greatest sex researchers of the century."

But as the mere existence of this young man in front of me would suggest, the experiment was a failure, a fact revealed in a March 1997 article in the Archives of Adolescent and Pediatric Medicine. Authors Milton Diamond, a biologist at the University of Hawaii, and Keith Sigmundson, a psychiatrist from Victoria, British Columbia, documented how the twin had struggled against his imposed girlhood from the start. The paper set off shock waves in medical circles around the world, generating furious debate about the ongoing practice of sex reassignment (a procedure more common than anyone might think). It also raised troubling questions about the way the case was reported in the first place, why it took almost 20 years for a follow-up to reveal the actual outcome and why that follow-up was conducted not by Dr. Money but by outside researchers. The answers to these questions, fascinating for what they suggest about the mysteries of sexual identity, also bring to light a 30-year rivalry between eminent sex researchers, a rivalry whose very bitterness not only dictated how this most unsettling of medical tragedies was exposed but also may, in fact, have been the impetus behind the experiment in the first place.

But what for medicine has been a highly public scandal involving some of the biggest names in the world of sex research has been for the young man sitting in front of me a purely private catastrophe. Apart from two short television appearances (his face obscured, his voice disguised), he has never spoken on the record to a journalist and has never before told his story in full. For this article, he granted more than 20 hours of candid interviews and signed confidentiality waivers giving me exclusive access to a voluminous array of legal documents, therapists' notes, Child Guidance Clinic reports, IQ tests, medical records and psychological work-ups. He assisted me in obtaining interviews with his former therapists as well as with all of his family members, including his father, who, because of the painfulness of these events, had not spoken of them to anyone in more than 20 years.

The young man's sole condition for talking to me was that I withhold some details of his identity. Accordingly, I will not reveal the city where he was born and raised and continues to live, and I have agreed to invent pseudonyms for his parents, whom I will call Frank and Linda Thiessen, and his sole sibling, the identical twin brother, whom I will call Kevin. The physicians in his hometown I will identify by initials. The young man himself I will call, variously, John and Joan, the pseudonyms given for him by Diamond and Sigmundson in the journal article describing the macabre double life he has been obliged to live. No other details have been changed.

"My parents feel very guilty, as if the whole thing was their fault," John says. "But it wasn't like that. They did what they did out of kindness , and love and desperation. When you're desperate, you don't necessarily do all the right things."

The irony was that Frank and Linda Thiessen's life together had begun with such special promise. A young couple of rural, religious backgrounds, they grew up on farms near each other and met when Linda was just 15, Frank 17. Linda, an exceptionally pretty brunette, had spent much of her teens fighting off guys who were too fresh. Frank, a tall, shy fair-haired man, was different. "I thought, 'Well, he's not all hands,' "Linda recalls." 'I can relax with him.' " Three years later, at ages 18 and 20, they married and moved to a nearby city. Linda remembers Frank's joy soon after, upon learning that he was going to be the father of twins - and his euphoria when the brothers were born, on Aug. 22, 1965. "The nurse asked him, 'Is it boys or girls?' " Linda recalls. "And he said, 'I don't know! I just know there's two of 'em!' "

Shortly before the births, Frank had landed his highest-paying job ever, at a local unionized plant, and the couple now moved with their newborns into a sunny one-bedroom apartment on a quiet side street downtown. But when the twins were 7 months old, Linda noticed that their foreskins were closing, making it hard for them to urinate. Their pediatrician explained that the condition, called phimosis, was not rare and was easily remedied by circumcision. He referred them to a surgeon. The operations were scheduled for April 27, 1966, in the morning. Because Frank needed the family car to get to his job on the late shift, they brought the kids in the night before. "We weren't worried," Linda says. "We didn't know we had anything to worry about. "

But early the next morning, they were jarred from sleep by a ringing phone. It was the hospital. "There's been a slight accident," a nurse told Linda. "The doctor needs to see you right away."

In the children's ward, they were met by the surgeon. Grim-faced, businesslike, he told them that John had suffered a burn to his penis. Linda remembers being shocked into numbness by the news. "I sort of froze," she says. "I didn't cry. It was just like I turned to stone." Eventually she was able to gather herself enough to ask how their baby had been burned. The doctor seemed reluctant to give a full explanation - and it would, in fact, be months before the Thiessens would learn that the injury had been caused by an electro-cautery needle, a device sometimes used in circumcisions to seal blood vessels as it cuts. Through mechanical malfunction or doctor error, or both, a surge of intense heat had engulfed John's penis. "It was blackened," Linda says, recalling her first glimpse of his injury. "It was like a little string. And it went right up to the base, up to his body." Over the next few days, the burnt tissue dried and broke away in pieces.

John, with a catheter where his penis used to be remained in the hospital for the next several weeks, while Frank and Linda, frantic, watched as a parade of the city's top local specialists examined him. They gave little hope. Phallic reconstruction, a crude and makeshift expedient even today, was in its infancy in the 1960's - a fact made plain by the plastic surgeon when he described the limitations of a phallus that would be constructed from flesh farmed from John's thigh or abdomen: "Such a penis would not, of course, resemble a normal organ in color, texture or erectile capability," he wrote in a report to the Thiessens' lawyer. "It would serve as a conduit for urine, but that is all."

Even that was optimistic, according to a urologist: "Insofar as the future outlook is concerned," he wrote, "restoration of the penis as a functional organ is out of the question." A psychiatrist summarized John's emotional future this way: "He will be unable to consummate marriage or have normal heterosexual relations; he will have to recognize that he is incomplete, physically defective, and that he must live apart...."

Now desperate, Frank and Linda took baby John on a daylong train trip to the Mayo Clinic, in Rochester, Minn., where he was examined by a team of doctors who merely repeated the dire prognoses delivered by the Thiessens' local physicians. Back home, with nowhere to turn, the couple sank into a state of mute depression . Months passed during which they could not speak of John's injury even to each other. Then one evening in December 1966, some seven months after the accident, they saw a TV program that jolted them from their despondency.

On their small black-and-white television screen appeared a man identified as Dr. John Money. A suavely charismatic and handsome individual in his late 40s, bespectacled and with sleekly brushed-back hair, Dr. Money was speaking about the wonders of gender transformation taking place at the Johns Hopkins medical center, where he was a medical psychologist. Also on the program was a woman - one of the satisfied post-operative transsexuals who had recently been converted at Johns Hopkins.

Today, with the subject of transsexualism a staple of daytime talk shows, it's difficult to imagine just how alien the concept seemed on that December evening in 1966. Fourteen years earlier, a spate of publicity had attended the announcement by American ex-GI George Jorgensen that he had undergone surgical transformation to become Christine. But that operation, performed in Denmark, had been roundly criticized by American doctors, who refused to perform such surgeries. The subject had faded from view - until now, when Johns Hopkins announced that it had not only performed two male-to-female sex changes (a first in America) but also established the world's first Gender Identity Clinic, devoted solely to the practice of converting people from one sex to the other. Along with gynecologist Howard W. Jones Jr., the driving force behind Hopkins' pioneering work in the study and treatment of transsexuals was the man on the Thiessens' television screen: Dr. John Money.

"He was very self-confident, very confident about his opinions," Linda recalls of her first glimpse of the man who would have such a lasting effect on the Thiessen's lives. "He was saying that it could be that babies are born neutral and you can change their gender. Something told me that I should get in touch with this Dr. Money."

She wrote to him soon after and described what had happened to her child. Dr. Money responded promptly, she says. In a letter, he expressed great optimism about what could be done for her baby at Johns Hopkins and urged her to bring John to Baltimore without delay. He also happened to inquire, Linda says, about the twin brother whom she had mentioned in passing. "He asked if they were identical twins," Linda says. She informed him that they were. Dr. Money replied that he would like to run a test on the babies at Johns Hopkins, just to make sure.

After so many months of grim predictions, bleak prognoses and hopelessness, Dr. Money's words, Linda says, felt like a balm. "Someone," she says, "was finally listening. "

Dr. Money was, indeed, listening. But then, Linda's cry for help was one that he might have been waiting for his entire professional life.

At the time that the Thiessen family's plight became known to Dr. Money, he was already one of the most respected, if controversial, sex researchers in the world. Born in 1921 in New Zealand, Money had come to America at about age 26, received his Ph.D. in psychology from Harvard and then joined Johns Hopkins, where his rise as a researcher and clinician specializing in sexuality was meteoric. Within a decade of joining Hopkins, he was already widely credited as the man who had coined the term "gender identity" to describe a person's inner sense of himself or herself as male or female, and was the world's undisputed authority on the psychological ramifications of ambiguous genitalia. "I think he's a thoroughly ethical and professional person," says John Hampson, a child psychiatrist who co-authored a number of Money's groundbreaking papers on sexual development in the mid-1950s. "He was a very conscientious scientist when it comes to collecting data and making sure of what he's saying. I don't know very many social scientists who could match him in that regard." According to Hampson, Money's ability to persuade others to adopt his point of view is one of the psychologist's chief strengths: "He's a terribly good speaker, very organized and very persuasive in his recital of the facts regarding a case." Indeed, Hampson admits that Money is almost too good at the art of persuasion. "I think a lot of people were envious," says Hampson. "He's kind of a charismatic person, and some people dislike him. As a person, he was a little bit . . . oh . . . flamboyant; he might have been a little glib."

He was 8 years old when his father, after a long illness, died. "His death was not handled very well in our family," Money wrote. Three days after watching his father get mysteriously carried off to the hospital, the boy was told that his father had died. His shock was compounded by the trauma of being informed by an uncle that now he would have to be the man of the household. "That's rather heavy duty for an 8-year-old." Money wrote. "It had a great impact on me." Indeed. As an adult, Money would forever avoid the role of "man of the household." After one brief marriage ended, he never remarried, and he has never had children.

Following his father's death, Money was raised by his mother and spinster aunts. A solitary adolescent with passions for astronomy and archaeology, he also harbored ambitions to be a musician. His widowed mother could not afford piano lessons, so Money worked as a gardener on weekends to pay for music classes and used every spare moment to practice. It was an ambition doomed to disappointment, partly because Money had set the bar so high for himself: "It was difficult for me to have to admit that, irrespective of effort, I could never achieve in music the goal that I wanted to set for myself. I would not even be a good amateur."

Upon entering Victoria University, in Wellington, Money discovered a new passion into which he would channel his thwarted creativity: the science of psychology. Like so many drawn to the study of the mind and emotions, Money initially saw the discipline as a means of solving certain gnawing questions about himself. His first serious work in psychology, the thesis for his master's, concerned "creativity in musicians"; in it, Money writes, "I began to investigate my relative lack of success in comparison with that of other music students."

His later decision to narrow his studies to the psychology of sex had a similarly personal basis. Having lost his religious faith in his early 20s, Money increasingly reacted against what he saw as the repressive religious strictures of his upbringing and, in particular, the anti-masturbatory, anti-sexual fervor that went with them. The academic study of sexuality, which removed even the most outlandish practices from moral considerations and placed them in the "pure" realm of scientific inquiry, was for Money an emancipation. From now on, he would be a fierce proselytizer for sexual exploration. According to journalist John Heidenry, a personal confidant of Money's and author of the recent book What Wild Ecstacy, which traces Money's role as a major behind-the-scenes leader of the sexual revolution of the 1960s and '70s, the psychologist's sexual explorations were not confined to the lab, lecture hall or library. An acknowledged but discreet bisexual, Money engaged in affairs with a number of men and women - "some briefly," Heidenry writes, "others over a longer duration." Indeed, by the mid-1970s, with the sexual revolution in full rampage, Money would step out publicly as a champion of open marriage, nudism and the dissemination of explicit pornography. His promotion of the culture's sexual unbuttoning seemed boundless. "There is plenty of evidence that bisexual group sex can be as personally satisfying as a paired partnership, provided each partner is 'tuned in' on the same wavelength," he wrote in his 1975 pop-psych book, Sexual Signatures. A former patient who was treated by Money in the 1970's for a rare endocrine disorder recalls the psychologist once casually asking him if he'd ever had a "golden shower." The patient, a sexually inexperienced youth at the time, did not know what Money was talking about. "Getting pissed on," Money airily announced with the twinkling, slightly insinuating little smile with which he delivered such deliberately provocative comments.

According to colleagues and other former patients, such sexual frankness in conversation is a hallmark of Money's personal style. Dr. Fred Berlin, a professor of psychiatry at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and a colleague who considers Money one of his most important mentors, agrees that Money is aggressively outspoken. "Because he thinks it's important to desensitize people in discussing sexual issues, he will sometimes use four-letter words that others might find offensive," says Berlin. "Perhaps he could be a little more willing to compromise On that. But John is an opinionated person who isn't looking necessarily to do things differently from the way he's concluded is best."

But while Money's conclusions about the best approach to sexual matters merely raised eyebrows in the mid-1970's, they provoked outrage at the dawn of the more conservative 1980's. Undaunted, Money continued to push on into uncharted realms. In an April 14, 1980, article in Time , Money was sharply criticized for what looked dangerously like an endorsement of incest and pedophilia. "A childhood sexual experience, such as being the partner of a relative or of an older person, need not necessarily affect the child adversely," Money told Time . And according to a right-wing group critical of his teachings, Money reportedly told Paidika , a Dutch journal of pedophilia, "If I were to see the case of a boy aged 10 or 12 who's intensely attracted toward a man in his 20s or 30s, if the relationship is totally mutual, and the bonding is genuinely totally mutual, then I would not call it pathological in any way."

Money's response to criticism has been to launch counterattacks of his own, lambasting his adoptive country for a puritanical adherence to sexual taboos. In an autobiographical essay included in his book Venuses Penuses , Money describes himself as a "missionary" of sex - and points out, with a lofty and defiant pride, "It has not been as easy for society to change as it had been for me to find my own emancipation from the 20th-century legacy of fundamentalism and Victorianism in rural New Zealand."

Money's experimental, taboo-breaking approach to sex was paralleled in his professional career. Eschewing the well-traveled byways of sex research, Money sought out exotic corners of the field where he could be a pioneer. He found just such a relatively undiscovered realm of human sexuality while in the first year of his Ph.D. studies in psychology at Harvard. In 1948, in a social-relations course, he learned of a 15 year-old male who was born not with a penis but with a tiny, nublike phallus resembling a clitoris and who, at puberty, developed breasts. It was Money's first exposure to hermaphroditism - also known as intersexuality - a condition that, in its extreme or its milder forms, is estimated to occur once in every 2,000 births. Characterized by ambiguities of the external sex organs and the internal reproductive system, intersexuality is caused by any of a wide variety of genetic and hormonal irregularities, and can vary from a female born with a penis-sized clitoris and fused labia resembling a scrotum to a male born with a penis no bigger than a clitoris, undescended testes and a split scrotum indistinguishable from a vagina.

Money became fascinated with intersexuality and wrote his doctoral dissertation on the subject, which led to his invitation, in 1951, to join Johns Hopkins, where the world's largest clinic for the study of intersexual conditions had been established. Up until then, the syndrome had been studied solely from a biological perspective. Money came at it from a psychological angle and would make a name for himself as a pioneer in examining the mental and emotional repercussions of being born as neither boy nor girl. At Hopkins, he enlisted Hampson and Hampson's wife, Joan, to help him study some 105 intersex children and adults. Money claimed to have observed a striking fact about people who had been diagnosed with identical genital ambiguities and chromosomal makeups but who had been raised as members of the opposite sex: More than 95 percent of these intersexes fared equally well, psychologically, whether they had been raised as boys or as girls. To Money, this was proof that the primary factor that determined an intersexual child's gender identity was not biological traits but the way that the child was raised. He concluded that these children were born psychosexually undifferentiated.

This theory was the foundation on which Money based his recommendation to pediatric surgeons and endocrinologists that they surgically and hormonally stream intersexual newborns into whichever sex the doctors wished. Such surgeries would duly range from cutting down enlarged clitorises on mildly intersexual girls to performing full sex reversals on intersexual boys born with testicles but a penis deemed too small. Money's only provisos were that such "sex assignments" be done as early as possible - preferably within weeks of birth - and that once the sex was decided on, doctors and parents never waiver in their decision, for fear of introducing dangerous ambiguities into the child's mind. In terms of the possible nerve destruction caused by the amputation of genital appendages, Money assured doctors that according to studies he had conducted with the Hampsons, there was no evidence of loss of sensation. "We have sought information about erotic sensation from the dozen non-juvenile . . . women we have studied," he wrote in a 1955 paper. "None of the women . . . reported a loss of orgasm after clitoridectomy."

Money's protocols for the treatment of intersexual children hold to this day. Placing the greatest possible emphasis on the child's projected "erotic functioning" as an adult and taking into account that medical science had never perfected the reconstruction of injured, or tiny, penises, Money's recommendations meant that the vast majority of intersexual children, regardless of their chromosome status, would be turned into girls. Current guidelines dictate that to be assigned as a boy, the child must have a penis longer than 2.5 centimeters; a girl's clitoris is surgically reduced if it exceeds 1 centimeter.

By providing a seemingly solid psychological foundation for such surgeries, Money had, in a single stroke, offered physicians a relatively simple solution to one of the most vexing and emotionally fraught conundrums in medicine: how to deal with the birth of an intersexual child. As Money's colleague Dr. Berlin points out, "One can hardly begin to imagine what it's like for a parent when the first question - 'Is it a boy or a girl?' - results in a response from the physician that they're just not sure. John Money was one of those folks who, years ago, before this was even talked about, was out there doing his best trying to help families, trying to sort through what's obviously a difficult circumstance."

In a retrospective essay written in 1985 about his career as a sex researcher, Money offered crucial insight into the way he arrived at some of his more unusual theories about human sexual behavior. "I frequently find myself toying with concepts and working out potential hypotheses," he mused. "It is like playing a game of science fiction. . . . It is as much an art as the creative process in painting, music, drama or literature."

Money's theory that newborns are psychosexually neutral was both unorthodox and against the current climate of science, which for decades had centered on the critical role of chromosomes and hormones in determining sexual behavior. But if his colleagues considered Money's ideas to be science fiction, they weren't prepared to say so publicly. His papers outlining his theory became famous in his field, helping not only to propel him to international renown as a sex researcher but also to speed his rise up the ladder at Johns Hopkins, where he ascended from assistant to associate professor of medical psychology, teaching his theory of infant sexual development to generations of medical students. By 1965, the year of John and Kevin Thiessen's birth, Money's reputation was virtually unassailable. He had for more than a decade been head of Hopkins' Psychohormonal Research Unit (his clinic for treating and studying intersex kids), and he was shortly to help co-found Hopkins' groundbreaking Gender Identity Clinic - a coup that helped earn him a reputation, says John Hampson, as "the national authority on gender disorder."

There was, however, at least one researcher who was willing to question Money. He was a young graduate student at the University of Kansas. The son of struggling Ukrainian-Jewish immigrant parents, Milton Diamond, whom friends call Mickey, was raised in the Bronx, where he had sidestepped membership in the local street gangs for the life of a scholar. As an undergraduate majoring in biophysics at City College of New York, Diamond became fascinated by the role of hormones in the womb and their possible role in defining a person's gender identity and sexual orientation. In his late 20s, as a grad student in endocrinology at Kansas, he conducted animal research on the subject, injecting pregnant guinea pigs and rats with different hormone cocktails to see how pre-birth events would affect later sexual behavior. The evidence in Diamond's lab suggested a link between the hormones that bathe a developing fetus's brain and nervous system and its later sexual functioning. It was in an effort to raise funds for his continued research that Diamond applied for a grant from the National Science Foundation Committee for Research in Problems of Sex an application that required the submission of a research paper. For his topic, Diamond decided to write a response to Money's now-classic papers on sexual development.

Diamond's critique appeared in The Quarterly Review of Biology in 1965. Marshaling evidence from biology, psychology, psychiatry, anthropology and endocrinology to argue that gender identity is hardwired into the brain virtually from conception, the paper was an audacious challenge to Money's authority (especially coming from an unknown grad student at the University of Kansas). First addressing the theory about the psychosexual flexibility of intersexes, Diamond pointed out that such individuals suffer "a genetic or hormonal imbalance" in the womb. Diamond argued that even if intersexuals could be steered into one sex or the other as newborns, this was not necessarily evidence that rearing is more influential than biology. It might simply mean that the cells in their brains had undergone, in utero, an ambiguity of sexual differentiation similar to that of the cells in their genitals. In short, intersexes have an inborn, neurological capability to go both ways - a capability, Diamond hastened to point out, that genetically normal children certainly would not share.

Even a scientist less thin-skinned than John Money might have been stung by the calm, relentless logic of Diamond's attack - which, near the end, raised the most rudimentary, Science 101 objection to the widespread acceptance of Money's theory of psychosexual malleability in normal children. "To support [such a] theory," Diamond wrote, "we have been presented with no instance of a normal individual appearing as an unequivocal male and being reared successfully as a female."

It was a year and a half after Diamond had thrown down the gauntlet that Dr. Money received Linda Thiessen's letter describing the terrible circumcision accident that had befallen her baby boy.