- Skip to right header navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

How to Give Constructive Feedback to Creative Writing

December 14, 2020 // by Lindsay Ann // 1 Comment

Sharing is caring!

Do you wonder how to give constructive feedback on creative writing and poetry pieces created by student writers who have put their heart and soul into them?

I think all teachers struggle with this question to some extent. It is because we care.

This can lead to indecisive response to student work. We waste valuable time when we lack a plan for response and worry about the emotional reaction to our feedback.

In this post, I’m all about sharing practical strategies that will teach you how to best give constructive feedback.

I want you to feel as comfortable responding to creative writing assignments as analysis based writing or argumentative writing assignments so that you can help student writers grow without deflating their fragile egos.

Setting the Stage for Writing Feedback

I think that it’s important to remember the feeling associated with having someone else read our work.

When I was a student, it was always a mixture of anticipation and dread . Would my instructor like what I had written? Would my grade reflect the time and effort I had put into the assignment?

A couple of things before we discuss how to give constructive feedback…

👉 I think that it’s important to be clear with students upfront about the skills you’re looking for in a creative writing assignment. Frontload with exemplars and use creative writing exercises to practice skills. Then, when it comes time for students to write, they will know what they are expected to do as writers.

👉 At the same time, it’s important to focus on feedback during the writing process . This allows our response to be as readers rather than as evaluators.

👉 Finally, I think that it makes a BIG difference when you model your own creative process for students. The more I can show students that writing is messy and imperfect, that I go through the same process as them, the more my classroom dynamic shifts from teacher-centered to student-centered and collaborative. If you’re wondering how to give constructive feedback to students, ask them to give feedback to you first.

Constructive Feedback for Students

When it comes to student feedback, less is more. I’ve blogged about this before, but I’ll say it again (and again) (and…again).

Most students don’t care about our carefully-worded paragraphs. They want to be seen and heard , but they also want to be able to understand what they can do to improve.

This means that feedback should be direct, specific, and actionable . This means that we need to respond as readers , not evaluators. This means that we will leave a manageable amount of feedback to build a student’s momentum.

Strategies for How to Give Constructive Feedback

➡️ Only mark the lines you love the most. Highlight them, underline them, put a star in the margin. Choose a couple of these lines to comment on. What did you notice? What did you like/realize/want to know?

➡️ Focus on the skills taught in class. So, if you taught characterization and concrete details, give feedback specifically on those elements. Ask students to revisit resources/screencasts/examples, etc. to review these skills.

➡️ Focus on moments of clarity and confusion. Where did you, as a reader, make a connection or realize something important? Where were you confused?

➡️ Yin Yang Feedback

- Find something specific that you liked/enjoyed (and explain why/how ). Maybe it’s a bit of figurative language or a vivid image. Pair this with a suggestion for where the writer can continue to work on this same skill. Essentially, this is like saying, “See, here, you did this thing that I liked and enjoyed…can you do more of that over here?” Or, “As a reader, it seemed to me like your intent was x, y, or z when you wrote _________. I’m wondering if you can make this clearer when _________.

- What is the highest level of skill mastery you can observe? Find an example of success and talk about why/how it was successful. What is the most important skill that still needs to be developed? Find a place where the student can begin working on this skill.

- Where were you most engaged/interested in the story. Leave a quick note about what captured your attention. Where were you least engaged/interested? This type of teacher feedback encourages revision.

➡️ Be curious. Read through the draft and ask questions… only questions . This is a kind of constructive feedback students love to hate (because it makes them think ). I ask my students to respond and revise. This strategy rocks because it establishes feedback as a two-way conversation rather than a one-way lecture.

➡️ Have students direct your feedback by asking you questions about their work. Alternatively, you can ask students to reflect on how/where they have demonstrated the skills you’ve taught in class (or the goals they’ve set for themselves). Then, you simply read through and respond to their comments, sharing your thoughts and suggestions.

➡️ Use a writer’s workshop model in which you conference with students about their work. You can train students to lead in these conversations if you choose the 1:1 model. Alternatively, you can form writing circles in which you provide students examples of constructive feedback before asking students to take turns reading their work out loud and solicit feedback from group members. You can float between writing groups, joining the conversations as needed.

Final Thoughts

I hope that I’ve helped you learn more about how to give constructive feedback to creative writers.

As we become purposeful in our responses to students, the benefit is that we streamline our own systems and processes which allows us to feel better about the feedback we are giving and also the amount of time it takes to provide this feedback!

About Lindsay Ann

Lindsay has been teaching high school English in the burbs of Chicago for 19 years. She is passionate about helping English teachers find balance in their lives and teaching practice through practical feedback strategies and student-led learning strategies. She also geeks out about literary analysis, inquiry-based learning, and classroom technology integration. When Lindsay is not teaching, she enjoys playing with her two kids, running, and getting lost in a good book.

Related Posts

You may be interested in these posts from the same category.

Using Rhetorical Devices to Write More Effectively

Common Lit Curriculum: An Honest Review

Incorporating Media Analysis in English Language Arts Instruction

How to Write a Descriptive Essay: Creating a Vivid Picture with Words

The Power of Book Tasting in the Classroom

20 Short Stories Students Will Read Gladly

6 Fun Book Project Ideas

Tailoring Your English Curriculum to Diverse Learning Styles

Teacher Toolbox: Creative & Effective Measures of Academic Progress for the Classroom

10 Most Effective Teaching Strategies for English Teachers

Beyond Persuasion: Unlocking the Nuances of the AP Lang Argument Essay

Trauma Informed Education that Doesn’t Inflict Trauma on Educators?

Reader Interactions

[…] How to Give Constructive Feedback to Creative Writing […]

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

TWO WRITING TEACHERS

A meeting place for a world of reflective writers.

Using a Writing Survey

How do you get to know the writers in your classroom at the beginning of the school year? When I still had my own classroom, I took a writing sample on the first day of school and then scored the sample using our district’s rubric. This first-day assessment gave me a good idea of which students used paragraphs or had good control of mechanics or wrote with detail. As I look back, though, I wonder if this was a sufficient way to really know my students as writers.

For example, if you were to really know me as a writer you might know:

- I write a lot of stories about my daughters

- I need a deadline to actually get words on paper

- I want to write a professional book for teachers

- I tend to write in loud-ish places like my kitchen table or my backyard

- I haven’t used my writer’s notebook in over a year

- I love to write and I hate to write and I love the way this dichotomy makes me feel

- I struggle to find my voice in nonfiction

- I have writing mentors such as Kate DiCamillo, Katie Wood Ray, and my colleagues here at Two Writing Teachers

- I’ve encouraged many of my colleagues to become writers

You would not know any of those things about me as a writer if I simply gave you a writing sample. You would have to talk to me (preferably over coffee) to know me as a writer. I regret not taking the time to understand my students better as writers.

I think it takes many weeks of writing and conversation and sharing to begin to uncover the writing identities of students. There is no quick and easy method. However, a writing survey at the beginning of the school year is a step in the right direction and can serve as a springboard for conversations to come. Some questions you might ask:

If you had to choose a room to write in, what would it sound like? Would it be silent? Would there be a TV or radio playing in the background?

If you could only write about one thing all year long, what would that be?

Imagine yourself fifteen years from now, a famous published author. What did you write?

Is there anyone whose writing you really admire?

Do you prefer to write with pencil/pen or on a computer?

Have you ever had a bad writing experience?

Do you know any writers?

Where do you think writers get story ideas from?

What does “living like a writer” mean to you?

As I think about using a writing survey in classrooms this year, there are three caveats I will keep in mind:

- There is no substitute for good conversation. This survey will serve as a conversation starter, not as an assessment.

- There will be many students who have no identity as a writer. Many students will be unable to answer some of these questions. That is okay, too – the lack of an answer is all the answer I need.

- The survey could be completed using pen and paper. It could also be completed digitally on a Google Doc or Google Form. A third option would be to use the questions as ‘interview questions’ and complete the survey with each student one-on-one over the first few weeks of school.

Taking the time at the beginning of the school year to learn about students in this way will help me be a more responsive and empathetic writing teacher all year long.

(For more on getting to know your student writers, don’t miss Beth’s thoughtful post from earlier this week.)

Share this:

Published by Dana Murphy

Literacy Coach, Reader, Writer View all posts by Dana Murphy

8 thoughts on “ Using a Writing Survey ”

Love these questions; I’m a huge fan of making time for reflection/metacognitive ‘stuff’ 🙂 Curious if you’d have students glue this survey into their ntbk or whether you’d collect. Thank you!

Great idea to let students keep a copy of the survey. It’d be interesting to have them revisit their answers mid-way through the school year to reflect on how they are changing as writers.

I’m thinking these conversations could easily happen if the first month of school were dedicated to establishing writer’s notebooks (and routines/procedures for writing workshop). There’d be plenty of time for this kind of work so that it didn’t become yet another piece of paper kids were asked to fill out.

Help! I have been searching for some information on appropriate writing assessments for kindergarten. In my district, we are required to do pre and post assessments for each of the units of study. We begin on days 5,6 and 7 and do all three (narrative, informational and opinion). We use a scripted prompt, which is the same one we use for the post-assessments. I just don’t feel in my heart that this is appropriate for brand new kindergartners, as most of them have no idea what we are talking about with all these big words. I have seen them appear disillusioned and frustrated as they attempt to please us by giving us what we are asking. I plan to make an appeal, but I am looking for some thoughts from experts. Thank you in advance for any insight you might give.

Hi, Diane. My district does the same thing with all our units of study. Although we don’t give the prompts consecutively like that, we do use very formal language and directions. I have sympathize with your plight and agree that it can be overwhelming to the primary students. I am not sure how much leeway you have, but some things we have done to make the task more accessible to kids are: -providing them with a student sample prior to the assessment – making an anchor chart of the important things to remember after reading the directions – using demonstration writing to provide an example

Also, check out some of these posts from our archives that have to do with assessment and/or primary writing:

Looking at Student Writing

What’s An On-Demand?

Please keep us posted on how it turns out!

This is a great post! I love these questions for writers and plan to use it in my classroom. You are so right that the blank spaces where students cannot come up with an answer are part of the picture of the student as writer at this moment in time. It gives us a place to start.

I love the idea of a conversation! Many kids may write what they think you want on a survey, but may be more open in a conversation. Earlier this week, there was a post about how a more experienced teacher dissuaded a new teacher from looking at last year’s work,saying something like “I like to get to know them myself”. But if you trust your colleagues, their insights into the kids they spent 180+ days with are invaluable. I will pass this along to my colleagues – thank you!

I think your writing survey is a great idea. The students’ responses will also provide you with information listed above such as paragraphing, mechanics and detail. Used in conjunction with a piece of real writing for the writer’s own purposes, you will have a lovely snapshot of the writer.

Comments are closed.

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

Greater Good Science Center • Magazine • In Action • In Education

How Creative Writing Can Increase Students’ Resilience

Many of my seventh-grade students do not arrive at school ready to learn. Their families often face financial hardship and live in cramped quarters, which makes it difficult to focus on homework. The responsibility for cooking and taking care of younger siblings while parents work often falls on these twelve year olds’ small shoulders. Domestic violence and abuse are also not uncommon.

To help traumatized students overcome their personal and academic challenges, one of our first jobs as teachers is to build a sense of community. We need to communicate that we care and that we welcome them into the classroom just as they are. One of the best ways I’ve found to connect with my students, while also nurturing their reading and writing skills, is through creative writing.

For the past three years, I’ve invited students in my English Language Development (ELD) classes to observe their thoughts, sit with their emotions, and offer themselves and each other compassion through writing and sharing about their struggles. Creating a safe, respectful environment in which students’ stories matter invites the disengaged, the hopeless, and the numb to open up. Students realize that nobody is perfect and nobody’s life is perfect. In this kind of classroom community, they can take the necessary risks in order to learn, and they become more resilient when they stumble.

Fostering a growth mindset

One of the ways students can boost their academic performance and develop resilience is by building a growth mindset. Carol Dweck, Stanford University professor of psychology and author of the book Mindset , explains that people with a growth mindset focus on learning from mistakes and welcoming challenges rather than thinking they’re doomed to be dumb or unskillful. A growth mindset goes hand in hand with self-compassion: recognizing that everyone struggles and treating ourselves with kindness when we trip up.

One exercise I find very useful is to have students write a story about a time when they persevered when faced with a challenge—in class, sports, or a relationship. Some of the themes students explore include finally solving math problems, learning how to defend themselves, or having difficult conversations with parents.

I primed the pump by telling my students about something I struggled with—feeling left behind in staff meetings as my colleagues clicked their way through various computer applications. I confided that PowerPoint and Google Slides—tools (one might assume) that any teacher worth a paperweight has mastered—still eluded me. By admitting my deficiency to my students, asking for their help, and choosing to see the opportunity to remedy it every day in the classroom, I aimed to level the playing field with them. They may have been reading three or four grade levels behind, but they could slap a PowerPoint presentation together in their sleep.

For students, sharing their own stories of bravery, resilience, and determination brings these qualities to the forefront of their minds and helps solidify the belief that underlies a growth mindset: I can improve and grow . We know from research in neuroplasticity that when students take baby steps to achieve a goal and take pride in their accomplishments, they change their brains, growing new neural networks and fortifying existing ones. Neurons in the brain release the feel-good chemical dopamine, which plays a major role in motivating behavior toward rewards.

After writing about a few different personal topics, students choose one they want to publish on the bulletin boards at the back of the classroom. They learn to include the juicy details of their stories (who, what, when, where, why, and how), and they get help from their peers, who ask follow-up questions to prompt them to include more information. This peer editing builds their resilience in more ways than one—they make connections with each other by learning about each other’s lives, and they feel empowered by lending a hand.

In my experience, students are motivated to do this assignment because it helps them feel that their personal stories and emotions truly matter, despite how their other academics are going. One student named Alejandro chose to reflect on basketball and the persistence and time it took him to learn:

Hoops By Alejandro Gonzalez Being good takes time. One time my sister took me to a park and I saw people playing basketball. I noticed how good they were and decided I wanted to be like them. Still I told my sister that basketball looked hard and that I thought I couldn’t do it. She said,“You could do it if you tried. You’ll get the hang of it.” My dad bought me a backboard and hoop to play with. I was really happy, but the ball wasn’t making it in. Every time I got home from school, I would go straight to the backyard to play. I did that almost every day until little by little I was getting the hang of it. I also played with my friends. Every day after lunch we would meet at the basketball court to have a game. … I learned that you need to be patient and to practice a lot to get the hang of things. With a little bit of practice, patience, and hard work, anything is possible.

Originally, Alejandro wasn’t sure why he was in school and often lacked the motivation to learn. But writing about something he was passionate about and recalling the steps that led to his success reminded him of the determination and perseverance he had demonstrated in the past, nurturing a positive view of himself. It gave him a renewed sense of investment in learning English and eventually helped him succeed in his ELD class, as well.

Maintaining a hopeful outlook

Another way to build resilience in the face of external challenges is to shore up our inner reserves of hope —and I’ve found that poetry can serve as inspiration for this.

For the writing portion of the lesson, I invite students to “get inside” poems by replicating the underlying structure and trying their hand at writing their own verses. I create poem templates, where students fill in relevant blanks with their own ideas.

One poem I like to share is “So Much Happiness” by Naomi Shihab Nye. Its lines “Even the fact that you once lived in a peaceful tree house / and now live over a quarry of noise and dust / cannot make you unhappy” remind us that, despite the unpleasant events that occur in our lives, it’s our choice whether to allow them to interfere with our happiness. The speaker, who “love[s] even the floor which needs to be swept, the soiled linens, and scratched records,” has a persistently sunny outlook.

It’s unrealistic for students who hear gunshots at night to be bubbling over with happiness the next morning. Still, the routine of the school day and the sense of community—jokes with friends, a shared bag of hot chips for breakfast, and a creative outlet—do bolster these kids. They have an unmistakable drive to keep going, a life force that may even burn brighter because they take nothing for granted—not even the breath in their bodies, life itself.

Itzayana was one of those students who, due to the adversity in her life, seemed too old for her years. She rarely smiled and started the school year with a defiant approach to me and school in general, cursing frequently in the classroom. Itzayana’s version of “So Much Happiness” hinted at some of the challenges I had suspected she had in her home life:

It is difficult to know what to do with so much happiness. Even the fact that you once heard your family laughing and now hear them yelling at each other cannot make you unhappy. Everything has a life of its own, it too could wake up filled with possibilities of tamales and horchata and love even scrubbing the floor, washing dishes, and cleaning your room. Since there is no place large enough to contain so much happiness, help people in need, help your family, and take care of yourself. —Itzayana C.

Her ending lines, “Since there is no place large enough to contain so much happiness, / help people in need, help your family, and take care of yourself,” showed her growing awareness of the need for self-care as she continued to support her family and others around her. This is a clear sign of her developing resilience.

Poetry is packed with emotion, and writing their own poems allows students to grapple with their own often-turbulent inner lives. One student commented on the process, saying, “By writing poems, I’ve learned to be calm and patient, especially when I get mad about something dumb.” Another student showed pride in having her writing published; she reflected, “I feel good because other kids can use it for calming down when they’re angry.”

To ease students into the creative process, sometimes we also write poems together as a class. We brainstorm lines to include, inviting the silly as well as the poignant and creating something that represents our community.

Practicing kindness

Besides offering my students new ways of thinking about themselves, I also invite them to take kind actions toward themselves and others.

In the music video for “Give a Little Love” by Noah and the Whale, one young African American boy—who witnesses bullying at school and neglect in his neighborhood —decides to take positive action and whitewash a wall of graffiti. Throughout the video, people witness others’ random acts of kindness, and then go on to do their own bit.

“My love is my whole being / And I’ve shared what I could,” the lyrics say—a reminder that our actions speak louder than our words and do have an incredible impact. The final refrain in the song—“Well if you are (what you love) / And you do (what you love) /...What you share with the world is what it keeps of you”—urges the students to contribute in a positive way to the classroom, the school campus, and their larger community.

After watching the video, I ask students to reflect upon what kind of community they would like to be part of and what makes them feel safe at school. They write their answers—for example, not being laughed at by their peers and being listened to—on Post-it notes. These notes are used to create classroom rules. This activity sends a message early on that we are co-creating our communal experience together. Students also write their own versions of the lyrics, reflecting on different things you can give and receive—like kindness, peace, love, and ice cream.

Reaping the benefits

To see how creative writing impacts students, I invite them to rate their resilience through a self-compassion survey at the start of the school year and again in the spring. Last year, two-thirds of students surveyed increased in self-compassion; Alejandro grew his self-compassion by 20 percent. The program seems to work at developing their reading and writing skills, as well: At the middle of the school year, 40 percent of my students moved up to the next level of ELD, compared to 20 percent the previous year.

As a teacher, my goal is to meet students where they’re at and learn about their whole lives. Through creative writing activities, we create a community of compassionate and expressive learners who bear witness to the impact of trauma in each others’ experiences and together build resilience.

As a symbol of community and strength, I had a poster in my classroom of a boat at sea with hundreds of refugees standing shoulder to shoulder looking skyward. It’s a hauntingly beautiful image of our ability to risk it all for a better life, as many of my ELD students do. Recognizing our common humanity and being able to share about our struggles not only leads to some beautiful writing, but also some brave hearts.

About the Author

Laura Bean, M.F.A. , executive director of Mindful Literacy, consults with school communities to implement mindfulness and creative writing programs. She has an M.F.A. in Creative Writing and presented a mindful writing workshop at Bridging the Hearts and Minds of Youth Conference in San Diego in 2016.

You May Also Enjoy

How to Help Low-Income Students Succeed

Five Ways to Support Students Affected by Trauma

Can Social-Emotional Learning Help Disadvantaged Students?

How to Help a Traumatized Child in the Classroom

How Teachers Can Help Immigrant Kids Feel Safe

How to Help Students Feel Powerful at School

- Home div.mega__menu -->

- Guiding Principles

- Assessment Cycle

- Equity in Assessment

- FAQs About Assessment

- Learning Outcomes & Evidence

- Undergraduate Learning Goals & Outcomes

- University Assessment Reports

- Program Assessment Reports

- University Survey Reports

- Assessment in Action

- Internal Assessment Grant

- Celebrating Assessment at LMU

- Assessment Advisory Committee

- Workshops & Events

- Assessment Resources

- Recommended Websites

- Recommended Books

- Contact div.mega__menu -->

Creative Writing Example Rubric

|

| 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Students will write well organized, cohesive papers.

| Work functions well as a whole. Piece has a clear flow and a sense of purpose. | Response has either a strong lead, developed body, or satisfying conclusion, but not all three. | Uneven. Awkward or missing transitions. Weakly unified. | Wanders. Repetitive. Inconclusive. | Incoherent and fragmentary. Student didn't write enough to judge. |

| Students will use appropriate voice and tone in writing.

| Voice is confident and appropriate. Consistently engaging. Active, not passive voice. Natural. A strong sense of both authorship and audience. | The speaker sounds as if he or she cares too little or too much about the topic. Or the voice fades in and out. Occasionally passive. | Tone is okay. But the paper could have been written by anyone. Apathetic or artificial. Overly formal or informal. | "I just want to get this over with." | Mechanical and cognitive problems so basic that tone doesn't even figure in. Student didn't write enough to judge. |

| Students will demonstrate original, creative writing.

| Excellent use of imagery; similes; vivid, detailed descriptions; figurative language; puns; wordplay; metaphor; irony. Surprises the reader with unusual associations, breaks conventions, thwarts expectations. | Some startling images, a few stunning associative leaps with a weak conclusion or lesser, more ordinary images and comparisons. Inconsistent. | Sentimental, predictable, or cliché. | Borrows ideas or images from popular culture in an unreflective way. | Cursory response. Obvious lack of motivation and/or poor understanding of the assignment. |

Rubric is a modification of one presented by: University Community Links (n.d.). Hot writing rubric. Retrieved August 19, 2008 from http://www.uclinks.org/reference/evaluation/HOT.html

Virtual Tour

Experience University of Idaho with a virtual tour. Explore now

- Discover a Career

- Find a Major

- Experience U of I Life

More Resources

- Admitted Students

- International Students

Take Action

- Find Financial Aid

- View Deadlines

- Find Your Rep

Helping to ensure U of I is a safe and engaging place for students to learn and be successful. Read about Title IX.

Get Involved

- Clubs & Volunteer Opportunities

- Recreation and Wellbeing

- Student Government

- Student Sustainability Cooperative

- Academic Assistance

- Safety & Security

- Career Services

- Health & Wellness Services

- Register for Classes

- Dates & Deadlines

- Financial Aid

- Sustainable Solutions

- U of I Library

- Upcoming Events

Review the events calendar.

Stay Connected

- Vandal Family Newsletter

- Here We Have Idaho Magazine

- Living on Campus

- Campus Safety

- About Moscow

The largest Vandal Family reunion of the year. Check dates.

Benefits and Services

- Vandal Voyagers Program

- Vandal License Plate

- Submit Class Notes

- Make a Gift

- View Events

- Alumni Chapters

- University Magazine

- Alumni Newsletter

SlateConnect

U of I's web-based retention and advising tool provides an efficient way to guide and support students on their road to graduation. Login to SlateConnect.

Common Tools

- Administrative Procedures Manual (APM)

- Class Schedule

- OIT Tech Support

- Academic Dates & Deadlines

- U of I Retirees Association

- Faculty Senate

- Staff Council

Writing Center

Undergraduate and General Support: Library Second Floor Room 215

Graduate Student, Postdoc, and Faculty Support: Idaho Commons Third Floor Room 323

Email: [email protected]

Web: Writing Center

Creative Writing Circle Survey

Creative Writing Interest Survey Back to School

- Google Apps™

What educators are saying

Also included in.

Description

During those first days of school, use this creative writing survey to learn more about your new students!

This resource includes a series of questions to help you discover students’ habits, preferences, strengths, and attitudes about writing, reading, and themselves.

Knowing details about your students will help you build relationships more quickly and guide you in developing a course that best fits your students’ needs.

WHAT’S INCLUDED:

- Twenty reflective questions for students

- Teacher tips page

- Printable PDF and Google Slides versions

- The Google Slides version contains text boxes for student responses. Due to copyright laws, the content is NOT editable for teachers.

CUSTOMER TIPS:

Be sure to follow my store to be alerted of new products. Look for the green star next to my store logo and click it to become a follower. You will now receive email updates about this store.

If you have any questions, I’d love to hear from you!

Questions & Answers

Ela lifesaver.

- We're hiring

- Help & FAQ

- Privacy policy

- Student privacy

- Terms of service

- Tell us what you think

Teaching creative writing in primary schools: a systematic review of the literature through the lens of reflexivity

- Open access

- Published: 17 June 2023

- Volume 51 , pages 1311–1330, ( 2024 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Georgina Barton ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2703-238X 1 ,

- Maryam Khosronejad 2 ,

- Mary Ryan 2 ,

- Lisa Kervin 3 &

- Debra Myhill 4

7351 Accesses

4 Citations

Explore all metrics

Teaching writing is complex and research related to approaches that support students’ understanding and outcomes in written assessment is prolific. Written aspects including text structure, purpose, and language conventions appear to be explicit elements teachers know how to teach. However, more qualitative and nuanced elements of writing such as authorial voice and creativity have received less attention. We conducted a systematic literature review on creativity and creative aspects of writing in primary classrooms by exploring research between 2011 and 2020. The review yielded 172 articles with 25 satisfying established criteria. Using Archer’s critical realist theory of reflexivity we report on personal, structural, and cultural emergent properties that surround the practice of creative writing. Implications and recommendations for improved practice are shared for school leaders, teachers, preservice teachers, students, and policy makers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Re-imagining narrative writing and assessment: a post-NAPLAN craft-based rubric for creative writing

Radical rubrics: implementing the critical and creative thinking general capability through an ecological approach

Autofictionalizing Reflective Writing Pedagogies: Risks and Possibilities

Explore related subjects.

- Artificial Intelligence

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Creative writing in schools is an important part of learning, assessment, and reporting, however, there is evidence globally to suggest that such writing is often stifled in preference to quick on-demand writing, usually featured in high-stakes testing (Au & Gourd, 2013 ; Gibson & Ewing, 2020 ). Research points to this negatively impacting particularly on students from diverse backgrounds (Mahmood et al., 2020 ). When teachers teach on-demand writing typical pedagogical traits are revealed, those that are often referred to as formulaic (Ryan & Barton, 2014 ). When thinking about creative writing, however, Wyse et al. ( 2013 ) noted that it involves the absence of structure and teaching creative writing requires an ‘open’ pedagogical approach for students to be given imaginative choice. By this, they mean that teachers need to consider less formulaic ways to teach writing so that students can experience different opportunities and ways to write creatively. They argued that if students are not given the flexibility to experiment through writing then their creativity might be stifled. Similarly, Barbot et al. ( 2012 ), who carried out a study with a panel of 15 experts of creative writing, posited that creative writing is when students draw on their imagination and other creative processes to create fictional narratives or writing that is ‘unusually original’. They also noted that creative writing is important for the development of students’ critical and creative thinking skills and ways in which they can approach life in creative ways.

Creative writing is defined in various ways in literature. Wang ( 2019 ) defined creative writing as a form of original expression involving an author’s imagination to engage a reader. Other definitions of creative writing involve the notion of children’s imagination, choice, and originality and much research has explored the concept of creativity within and through the writing process.

While creative writing is defined in various ways, and the many ways that it is treated in literacy education, this article is not concerned with the nature of the term per se. Rather, it focusses on research about creative writing and creativity in writing to understand how research unpacks the personal and contextual characteristics that surround creative writing practices. To this aim, we adopt a broad definition of creative writing as a form of original writing involving an author’s imagination and self-expression to engage a reader (Wang, 2019 ). Creative writing is important for children’s development (Grainger et al., 2005 ), allowing them to use their imagination and broaden their ability to problem-solve and think deeply. Creativity in writing refers to specific aspects within a writing product that can be deemed creative. Some examples include the use of senses and how a writer might engage a reader (Deutsch, 2014 ; Smith, 2020 ).

International research on teaching writing has indicated a loss in innovative or creative pedagogical practices due to the pressure on teachers to teach prescribed writing skills that are assessed in high-stakes tests (Göçen, 2019 ; Stock & Molloy, 2020 ), often resulting in specific trends including teaching a genre approach to writing (Polesel et al., 2012 ; Ryan & Barton, 2014 ). A comprehensive meta-analysis by Graham et al ( 2012 ), designed to identify writing practices with evidence of effectiveness in primary classrooms, found that explicitly teaching imagery and creativity was an effective teaching practice in writing. In addition, a review of methods related to teaching writing conducted by Slavin et al. ( 2019 ) included studies that statistically reported causal relationships between teacher practice and student outcomes. Common themes in Slavin et al’s ( 2019 ) quest for improving writing included comprehensive teacher professional development, student engagement and enjoyment, and explicit teaching of grammar, punctuation, and usage. While they did not specifically cite creativity, motivating environments and cooperative learning were important characteristics of writing programs.

This systematic literature review aims to share empirical international research in the context of elementary/primary schools by exploring creativity in writing and the conditions that influence its emergence. It specifically aims to answer the question: What influences the teaching of creative writing in primary education? And how can reflexivity theorise these influences? The review shares scholarly work that attempts to define personal aspects of creative writing including imagination, and creative thinking; discusses creative approaches to teaching writing, and shows how these methods might support students’ creative writing or creative aspects of writing.

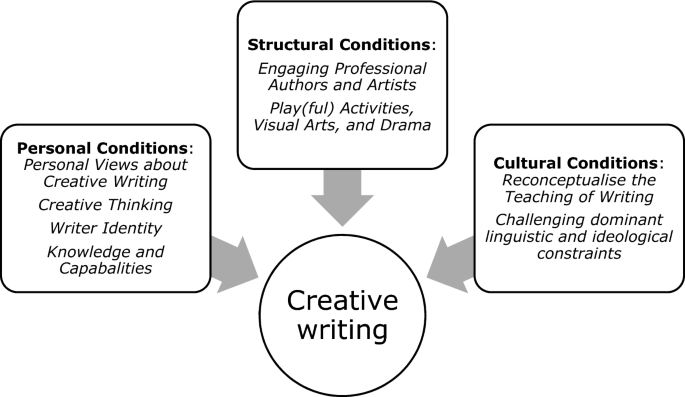

Writing is a complex process that involves students making decisions about word choice, sentence, and text structure, and ways in which to engage readers. Such decisions require a certain amount of reflection or at times deeper reflexive judgments by both teachers and students. Consequently, we draw on Archer’s ( 2012 ) critical realist theory of reflexivity to guide our review as research shows that reflexive thinking in practice can improve writing outcomes (Ryan et al., 2021 ). Archer ( 2007 ) highlights how reflexivity is an everyday activity involving mental processes whereby we think about ourselves in relation to our immediate personal, social, and cultural contexts. She suggests we make decisions through negotiating the connected emergences of personal properties (PEPs) related to the individual, structural properties (SEPs) related to the contextual happenings and cultural properties (CEPs) related to ideologies, each of which is influenced by the other developments. These decisions influence, and are influenced by, our subsequent actions. In applying reflexivity theory to writing (see Ryan, 2014 ), we cannot simply focus on the writing product, but should also interrogate the process of writing, that is, the influences on decision-making and design which are enabled or constrained through pedagogical practices in the classroom. Writing practices and outputs are formed through the interplay of personal, structural, and cultural conditions. Student decisions and actions about writing ensue through the mediation of personal (e.g. beliefs, motivations, interests, experiences), structural (e.g. curriculum, programs, testing regimes, teaching strategies, resources), and cultural (e.g. norms, expectations, ideologies, values) conditions. Therefore, teachers play an important role in facilitating the interplay of these conditions for their students and recontextualising curricula and policy (Ryan et al., 2021 ). For example, by enabling students’ agency and creating an authentic purpose for writing, teachers can balance the personal conditions of students (such as their motivation and interest) against the structural effects of the curriculum requirements. Using a reflexive approach to investigating the literature on creative writing we aim to reveal the personal, structural, and cultural conditions surrounding the study and the practice of creative writing. We argue that it is through the understanding of these conditions that we can theorise how a. students might make their writing more creative and b. how teachers might establish classroom conditions conducive to creativity.

The approach taken for this paper was guided by the PRISMA method (Moher et al., 2009 ) for conducting systematic literature reviews (see Table 1 ).

Our electronic search involved several databases: researchers’ library online catalogue, EBSCO host ultimate, ProQuest, Eric, Web of Science, Informit, and ScienceDirect. Using the following search terms: creativ* AND (‘teaching methods’ OR pedagog*) AND writing AND (elementary OR primary) to search titles and abstracts as well as limiting the search to peer-reviewed articles written in English within a 10-year timeframe (2011–2020), we initially retrieved 172 articles. Information about all 172 articles was input into a data spreadsheet including author, article title, journal title, volume and issue number, and abstract. Once completed, these articles were divided into two equal groups and two researchers were assigned to review the articles for relevancy against the following inclusion criteria:

Studies were peer-reviewed empirical research published in English;

Participants were primary students and/or teachers;

Students were not specifically English as a Second or Additional Language/Dialect learners (samples of culturally and linguistically diverse students in primary classrooms were included);

Studies were not carried out in curriculum areas other than English; and

Studies did not have a specific focus on digital technologies in the classroom.

For this systematic review, we were interested in the ways in which teachers thought about, understood, and taught the ‘creative’ aspect of writing.

The 25 studies that met the inclusion criteria were synthesised to review what influences the improvement of creative writing in primary education. We analysed the papers for how creative writing and/or creative aspects in writing were viewed as well as how teachers might best support students to develop reflexive capacities to improve the creative aspects of writing. We also identified any personal, structural, and/or cultural emergences that might impact on the effectiveness of students’ creative writing. Two of the authors read the entire articles and identified four main categories of research which were (1) understanding creative writing; (2) creative thinking and its contribution to writing; (3) creative pedagogy; and (4) what students can do to be more creative in their writing. These were cross-checked by the entire research team. Some of the papers fit more than one of these themes. In the next section, each theme is introduced and defined and then the articles that fall within the theme are reviewed.

Overall a total number of 25 articles had overlapping themes that included various personal and contextual aspects. Figure 1 shows what we have identified as the key themes under each category. In the next sections, we represent papers based on their main theme.

The personal, structural, and cultural conditions surrounding creative writing

Personal emergent properties

A total number of 13 articles were about what students can do to be more creative in their writing (Mendelowitz, 2014 ; Steele, 2016 ) and how teachers’ and students’ personal characteristics relate to the development of creative writing. These articles were mainly focussed on the personal emergent aspects of writing (Alhusaini & Maker, 2015 ; Barbot et al., 2012 ; Cremin et al., 2020 ; DeFauw, 2018 ; Dobson, 2015 ; Dobson & Stephenson, 2017 , 2020 ; Edwards-Groves, 2011 ; Healey, 2019 ; Lee & Enciso, 2017 ; Macken-Horarik, 2012 ; Ryan, 2014 ). The personal aspects identified in our review were (1) personal views about creative writing, (2) creative thinking, (3) writer identity, (4) learner motivation and engagement, and (5) knowledge and capabilities.

Personal views about creative writing

From our systematic review, we identified three articles exploring views about what creative writing is, and more specifically the role that it plays and the elements that make creative writing, in primary classrooms. One of these studies was focussed on the views and experiences of experts in writing (Barbot et al., 2012 ), whereas the other two investigated students’ perspectives and experiences (Alhusaini & Maker, 2015 ; Healey, 2019 ). Barbot et al’s ( 2012 ) work, for example, recognised that creative writing involves both cognitive and metacognitive abilities. This was determined by the expert panel of people whose work related to writing including teachers, linguists, psychologists, professional writers, and art educators. The panel were asked to complete an online survey that rated the relative importance of 28 identified skills needed to creatively write. Six broad categories were identified as a result of the responses and the rank given to each factor by the expert groups (See Table 2 ). They acknowledged that these features cross over various age groups from children to professional writers.

Findings suggested that each independent rater weighted different key components of creative writing as being more or less important for children. Overall, the findings showed.

a global ‘consensus’ across the expert groups indicated that creative writing skills are primarily supported by factors such as observation, generation of description, imagination, intrinsic motivation and perseverance, while the contributions of all of the other relevant factors seemed negligible (e.g. intelligence, working memory, extrinsic motivation and penmanship). (p. 218)

One factor that was ranked as critical by most respondents, but underemphasised by teachers, was imagination. Teachers’ work in classrooms around creative writing is complex due to the difficulty in defining imagination (Brill, 2004 ). Teachers also under-rated other aspects related to creative cognition.

Another study that explored students’ creativity in writing was conducted by Alhusaini and Maker ( 2015 ) in the south-west of the United States. Participants included 139 students with mixed ethnicities including White, Mexican American, and Navajo. This study involved six elementary/primary school teachers judging students’ writing samples of open-ended stories. To assess the work a Written Linguistic Assessment tool, which was based on the Consensual Assessment Technique [CAT] (Amabile, 1982 ) was implemented. According to Baer and McKool ( 2009 ), The CAT involves experts rating written artefacts or artistic objects by using their ‘sense of what is creative in the domain in question to rate the creativity of the products in relation to one another’ (p. 4). Interestingly, Alhusaini and Maker ( 2015 ) found the CAT to be effective in relation to interrater reliability. The authors do not share what the Judge’s Guidelines to Assess Students’ Stories entail. They mention the difference between technical quality and creativity and note that assessors were able to distinguish the differences between the two, but the reader is not made aware of the aspects of each quality. Overall, the study revealed that one of the most challenging problems in the field of creativity and writing is trying to measure creativity across cultures by using standardised tests. Such studies could have implications for other students from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds as teachers become more aware of cultural nuances in constituting ‘creative’ in creative writing.

The final study we identified in this category was by Healey ( 2019 ). Healey employed an Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) and explored how eight children (11–12 Years of age) experienced creative writing in the classroom. He shared how children’s writing experiences were based on ‘the affect, embodiment, and materiality of their immediate engagement with activities in the classroom’ (p. 184). Results from student interviews showed three themes related to the experience of writing: the writing world (watching, ideas from elsewhere, flowing); the self (concealing and revealing, agency, adequacy); and schooled writing (standards, satisfying task requirements, rules of good writing). The author stated that children’s consciousness shifts between their imagination (The Writing World) and set assessment tasks (Schooled Writing). Both of these worlds affect the way children experience themselves as writers. Further findings from this work argued that originality of ideas and use of richer vocabulary improved students’ creative writing. Vocabulary improvement included diversity of word meanings, appropriate usage of words, words being in line with the purpose of the text; while originality of ideas featured creative and unusual (original) ideas—which in many ways is difficult to define.

Overall, when concerned with personal views and attitudes in creative writing, the two studies by Healey ( 2019 ) and Barbot et al. ( 2012 ) show contrasting findings about ‘imagination’ captured through the view of students and teachers, respectively. While Healey’s ( 2019 ) study suggests that children shift between their imagination and set assessment tasks in creative writing, Barbot et al. ( 2012 ) highlight the lack of attention to imagination among their participated teachers. Although these results cannot be generalised, they highlight the significance of understanding personal emergent properties that both students and teachers bring to the classroom and the way that they interact to affect the experience of creative writing for learners. From this theme, we suggest the importance of educators acknowledging students’ imagination through their definition of creative writing as well as providing quality time for students to choose what they write through imaginative thought. We now turn to creative thinking and related pedagogical approaches to teaching creative writing from the research literature.

Creative thinking

We identified two articles that were focussed on creative thinking and its contribution to writing (Copping, 2018 ; Cress & Holm, 2016 ). Copping ( 2018 ) explored writing pedagogy and the connections between children’s creative thinking, or a ‘new way of looking at something’ (p. 309), and their writing achievement. The study involved two primary schools in Lancashire, one in an affluent area and one in an underprivileged area. Approximately 28 children from each school were involved in two, 2-day writing workshops based on a murder mystery the children had to solve. Findings from this study revealed that to improve students’ writing achievement (1) a thinking environment needs to be created and maintained, (2) production processes should have value, (3) motivation and achievement increase when there is a tangible purpose, and (4) high expectations lead to higher attainment.

Cress and Holm’s ( 2016 ) study described a curricular approach implemented by a first-grade teacher and their class comprised 13 girls and 11 boys. The project known as the Creative Endeavours project aimed to develop creative thinking by (1) creating an environment of respect with a positive classroom climate. (2) offering new and challenging experiences, and (3) encouraging new ideas rather than praise. The authors argued that through peer collaboration and the flexibility to choose their own projects, children can become more authentically engaged in the writing process. The children wrote about their experiences and their choices, and reflected upon the projects undertaken. In this study, it was revealed that the children showed diversity in their writing assignments including presentation through sewing, photography, and drama. While there were only two papers in this particular theme, their findings are supported by systematic reviews (Graham et al., 2012 ; Slavin et al., 2019 ) that emphasise not only new ways of exploring a range of concepts for learning but also the creation of motivating environments for improving writing (Copping, 2018 ). In addition to the significance of positive and encouraging learning environments, these two studies suggest that setting ‘high expectations’ or ‘challenging experiences’ are conducive to creative thinking however, teachers would need to set appropriate, reflexive conditions for this to occur.

Writer identity

Studies in this category revolve around choice and learner writer identity. The study carried out by Dobson and Stephenson ( 2017 ) focussed on developing a community of writers involving 25 primary school pupils from low socio-economic backgrounds. The project was offered over 2 weeks and featured a number of creative writing workshops. The authors applied the theoretical frameworks of practitioner enquiry and discourse analysis to explore the children’s creative writing outputs. They argued that the workshops, which promoted intertextuality and freedom for the children as writers, enabled a shifting of their ‘writer’ identities (Holland et al., 1998). Dobson and Stephenson ( 2017 ) showed that allowing students to make decisions and choices in regard to authentic writing purposes supported a more flexible approach. They recommend stronger partnerships between schools and universities in relation to research on creative writing, however, it would be important for these relationships to be sustainable.

The second paper on this theme is by Ryan ( 2014 ) who noted that writing is a complex activity that requires appropriate thinking in relation to the purpose, audience, and medium of a variety of texts. Writers always make decisions about how they will present subject matter and/or feelings through all of the modes. Ryan ( 2014 ) suggested that writing is like a performance ‘whereby writers shape and represent their identities as they mediate social structures and personal considerations’ (p. 130). The study analysed writing samples of culturally and linguistically diverse Australian primary students to uncover the types of identities students shared. It found that three different types of writers existed—the school writers who followed teacher instructions or formulas to produce a product; the constrained writers who also followed instructions and formulas but were able to add in some authorical voice; and the reflexive writers who could show a definite command of writing and showed creative potential. Ryan ( 2014 ) argued that teachers’ practices in the classroom directly influence the ways in which students express these identities. She stated that when students are provided choices in writing, they are more able to shape and develop their voices. Such choices would need to include quality time and support to be reflexive in the decisions being made by the students.

The Teachers as Writers project (2015–2017) was conducted by Cremin, Myhill, Eyres, Nash, Wilson, and Oliver. In a recent paper ( 2020 ), the team reported on a collaborative partnership between two universities and a creative writing foundation. Professional writers were invited to engage with teachers in the writing process and the impact of these interactions on classroom teaching practices was determined. Data sets included observations, interviews, audio-capture (of workshops, tutorials and co-mentoring reflections), and audio-diaries from 16 teachers; and a randomised controlled trial (RCT) involving 32 primary and secondary classes. An intervention was carried out involving teachers writing in a week long residence with professional writers, one-on-one tutorials, and extra time and space to write. They also continued learning through two Continuing Professional Development (CPD) days. Results showed that teachers’ identities as writers shifted greatly due to their engagement with professional authors. The students responded positively in terms of their motivation, confidence, sense of ownership, and skills as writers. The professional authors also commented on positive impacts including their own contributions to schools. Conversely, these changes in practice did not improve the students’ final assessment results in any significant way. The authors noted that assuming a causal relationship between teachers’ engagement with writing workshops and students’ writing outcomes was spurious. They, therefore, developed further research building on this learning.

Knowledge and capabilities

The role of knowledge and capability is central to the articles in this category. In Australia, Macken-Horarik ( 2012 ) reported on the introduction of a national curriculum for English. This article drew on Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL) by investigating the potential of Halliday’s notion of grammatics for understanding students’ writing as acts of creative meaning in context. Macken-Horarik ( 2012 ) argued that students needed to know deeply about language so that they could make creative decisions with their writing. She outlined that a ‘good enough’ grammatics would assist teachers in becoming comfortable with ‘playful developments in students’ texts and to foster their control of literate discourse’ (p. 179).

A project carried out by Edwards-Groves in 2011 highlights the role of knowledge about digital technologies in writing practices. 17 teachers in primary classrooms in Australia were asked to use particular digital technologies with their students when constructing classroom texts. Findings showed that an extended perspective on what counts as writing including the writing process was needed. Results revealed that collaborative methods when constructing diverse texts required teachers to rethink pedagogies towards writing instruction and what they consider as writing. It was argued that technology can be used to enhance creative possibilities for students in the form of new and dynamic texts. In particular, it was noted that teachers and students should be aware that digital technologies can both constrain and/or enable text creation in the classroom depending on a number of variables including knowledge and understanding, locating resources and logistical issues such as connectivity and reliability.

In addition, Mendelowitz’s ( 2014 ) study argued that nurturing teachers’ own creativity assisted their ability to teach writing more generally. She noted several ‘interrelated variables and relationships that still need to be given attention in order to gain a more holistic understanding of the challenges of teaching creative writing’ (p. 164). According to Mendelowitz ( 2014 ), elements that impacted on these challenges include teachers’ school writing histories, conceptualisations of imagination, classroom discourses, and pedagogy. Documenting teachers’ work through interviews and classroom observations by the researcher, the study found that teachers need to be able to define imagination and imaginative writing and know what strategies work best with their students. She noted that the teacher’s approaches to teaching writing ‘powerfully shaped by the interactions between their conceptualisations and enactments of imaginative writing pedagogy’ (p. 181) and that these may either limit or create a space for students to be more creative with their writing.

Such Personal Emergent Properties show that individual attributes of both teachers and students are important in learning creative writing. The next section of the paper explores the articles that shared various structural and cultural properties.

Structural emergent properties

In the subset of structural emergent properties, we mainly identified pedagogical approaches for creative writing that explored primary school learning and teaching (Christianakis, 2011a ; Christianakis, 2011b ; Coles, 2017 ; DeFauw, 2018 ; Hall & Grisham-Brown, 2011 ; Portier et al., 2019 ; Rumney et al., 2016 ; Sears, 2012 ; Steele, 2016 ; Southern et al., 2020 ; Yoo & Carter, 2017 ). These pedagogical approaches were aimed at addressing issues related to personal emergent properties such as motivation and engagement, and confidence in writing. The two categories of writing pedagogies were those that engaged professional authors and artists in teaching about creative writing, and the approaches that involved play(ful) activities, and use of visual arts, and drama.

Engaging professional authors and artists

Interestingly, many of the studies used literary forms and/or professional creative authors to spike interest and motivation in the students. Coles’ ( 2017 ) study, for example, used a garden-themed poetry writing project to support 9–10-year-old children’s creative writing in a London primary school. The 5-week project partnered with a professional creative writing organisation that facilitated the Ministry for Stories (MoS) writing centres across the USA. The study found that the social relationships created through this partnership allowed for a more inclusive and socially generative model of creativity. This meant that teachers should not just include creative aspects in assessment rubrics but rather recognise that creativity is encouraged through imagination and working with others. The researchers found improvements in the children’s participation in classroom writing activities as well as diversity in the ways they expressed their writing. The approach valued ‘rich means of expression rather than a set of rules to be learnt’ (p. 396). They also acknowledged issues associated with school–community partnerships including the sustainability of the practice.

Similarly, Rumney et al. ( 2016 ) found that using creative multimodal activities increased students’ confidence and motivation for writing. The study implemented the Write Here project with over 900 children in 12 primary and secondary schools. The study involved the children visiting local art galleries to work with professional authors and artists. Case studies were presented about pre-writing activities, the actual gallery work and post-gallery follow-up sessions. It aimed to improve students’ social development and literacy outcomes through diverse learning activities such as visual art and play in different contexts such as art galleries and classrooms. Like Coles’ ( 2017 ) study, this project showed that creative activities (e.g. talking about and acting out pictures; using story maps; backwards writing and planning) engaged students more than just teaching skills.

In addition, DeFauw’s ( 2018 ) study had student-centred learning and leadership at the core when working with a children’s book author for one year. The collaboration involved three face-to-face sessions with the author as well as online communication through blog posts. Data included recorded interactions, readings and pre and post interviews with teachers ( n = 9), students ( n = 36), and the author. The partnership showed that students’ interest was activated and sustained due to the situational context as well as the extended time given to students to interact with the author. The project improved students’ interest in and motivation to write as a result of engaging with authors and hearing about their own experience and writing strategies. It also found that teachers gained more confidence to support students’ exploration of writing in more creative ways. The creative pedagogies were also used in addressing issues related to creative writing outcomes for students, including teachers’ lack of confidence about pedagogies (Southern et al., 2020 ). Through a creative social enterprise approach, the authors facilitated professional development and learning involving artist-led activities for students. The program called Zip Zap had been implemented in schools in Wales and England, and data were collected through focus groups with teachers, students, and parents/carers. Observations of some of the professional development workshops were also video recorded. Third space theory was used to describe the collaborative practice between educators and artists that supported students’ creative writing outcomes. It was noteworthy that involving ‘creative’ practitioners largely focussed on the specific strategies that could be used in classrooms, to which our next section now turns.

Play(ful) activities, visual arts, and drama

Much research explores how to best support students who find writing difficult. Sears’ research ( 2012 ) is a case in point. The author shared how visual arts may be an effective way to improve struggling students with writing. They argued that the visual arts can provide ways of ‘accessing and expressing [student] ideas and ultimately opening a world of creative possibilities’ (p. 17). In the study, six third-grade students engaged with drawing and painting as pre-writing strategies, leading to the creation of poems based on the artworks. The students’ final poems were assessed and showed improved knowledge of all 6 technical categories in writing: ideas, organisation, fluency, voice, word choice, and conventions. The author also argued that students’ motivation to write increased as a result of the visual art activities.

A study by Portier et al. ( 2019 ) investigated approaches to teaching writing that were motiving and engaging for students. Involving 10 northern rural communities in Canada, the project implemented collaborative, play(ful) learning activities alongside sixteen teachers and their students. Interestingly, the study, like many others in our review, found a disconnect ‘between the achievement of curricular objectives and the implementation of play(ful) learning activities’ (p. 20); an approach valued in early childhood education. The students were supported through action research projects in creating texts with different purposes. Students’ motivation as well as samples of work were analysed and showed that student interest areas and collaborative approaches benefited both teachers and students. Further research on how reflexive thinking might have influenced these benefits is recommended.

Similarly, Lee and Enciso ( 2017 ) highlighted the importance of motivation and engagement in their study. In a collaboration with Austin Theatre Alliance, Lee and Enciso ( 2017 ) investigated how dramatic approaches to teaching, such as through expanded imagination and improvisation, can improve students’ story writing. They argued that the students’ motivation to write was also increased. The study was carried out through a controlled quasi-experimental study over 8 weeks of story-writing and drama-based programs. 29 third-grade classrooms in various schools, located in an urban district of Texas, were involved. The study also pre- and post-tested the students’ writing self-efficacy through story building. The study found that students were more able to use their cultural knowledge such as ‘culturally formed repertoires of language and experience to explore and express new understandings of the world and themselves…’ (p. 160) for creative writing purposes but needed more quality resources to support opportunities such as the Literacy for Life program. A most important finding was that for children who experience poverty, drama-based activities developed and led by teaching artists were extremely powerful and allowed the students to express themselves in entertaining ways. We do note that ‘entertainment’ and or engagement might mean different things for different students so reflexive approaches to deciding what these are would be necessary.

Steele’s ( 2016 ) study also looked at supporting teachers’ work in the classroom. Involving 6 out of 20 teacher workshop participants in Hawaii, this exploratory case study utilised observations, interview, and portfolio analyses of teacher and student work. Findings from the study showed that some teachers relished moving away from everyday ‘typical’ practice and increased student voice and choice. Other teachers, however, found it difficult to take risks and hence respond to student needs and ideas.

Dobson and Stephenson’s ( 2020 ) study focussed on the professional development of primary school teachers using drama to develop creative writing across the curriculum. The project was sponsored by the United Kingdom Literacy Association and ran for two terms in a school year. Researchers based the research on a collaborative approach involving academics and four teachers working with theatre educators to use process drama. Data sets included lesson observations, notes taken during learning conversations, and interviews with the teachers. The findings showed that three of the four teachers resisted some of the methods used such as performance; resulting in a lack of child-centred learning. The remaining teacher could take on board innovative practice, which the researchers attributed to his disposition. The study argued that these teachers, while a small participant group, needed more support in feeling confident in implementing new and creative approaches to teaching writing.

The final study, identified as addressing creative pedagogies for creative writing, was carried out by Yoo and Carter ( 2017 ) as professional development for teachers. Data included teacher survey responses and field notes taken by the researchers at each workshop (note: number of workshops and participants is unknown). The program aimed to investigate how emotions play a role in teachers’ work when teaching creative writing. The researchers found that intuitive joint construction of meaning was important to meet the needs of both primary and secondary teachers. A community of practice was established to support teachers’ identities as writers (see also Cremin et al., 2020 ). Findings showed that teachers who already identified as writers engaged more positively in the workshop.

These studies presented some approaches for teachers to consider how to teach creative writing. For example, the need to value unique spaces for students to write, including authentic connections with people and places outside of school environments was shared. Further, the need for quality stimuli and time for writing was acknowledged. Several other studies identified that blended teaching approaches to support student learning outcomes in the area of creative writing is important for schools and teachers to consider. We do acknowledge there may be other methods available to support students in creative writing, however, understanding what types of SEPs are impacting on teaching creative writing is an important step in determining improvements in schools.

Cultural emergent properties

Christianakis ( 2011a , 2011b ) wrote two papers about children’s creative text development with an emphasis on the cultural aspects. The first was an ethnographic study across 8 months with a year five class in East San Francisco Bay. The study included audio recording the students’ conversations and analysing over 900 samples of work. In the classroom, students were involved in a range of meaning-making practices including those that were arts-based and multimodal. The conversations with the students involved the researcher asking questions such: tell me more about this drawing, how did you come up with the idea? or why did you make this choice? The study found that there was a need for schools to reconceptualise the teaching of writing ‘to include not only orthographic symbols, but also the wide array of communicative tools that children bring to writing’ (p. 22). The author argued that unless corresponding institutional practices and ideologies were interrogated then improved practice was unlikely.

Christianakis’ ( 2011b ) second article, from the same project, explored more specifically the creation of hybrid rap poems by the children. She explicated how educators needed to negotiate and challenge dominant practices in primary classroom literacy learning. Like many studies before, a strong recommendation was to be more inclusive of youth popular cultures and culturally relevant literacies for students to be more engaged in creative writing practices. For Christianakis, culturally relevant literacies meant practices that embraced diversity in class and race and accounted for, and challenged, the dominant hegemonic curriculum that ‘privileges a traditional canon’ (p. 1140).

In summary, we found several themes under PEPs that could be considered for further research including those outlined in Table 3 below.

Discussion and implications for classroom practice

From this systematic literature review, several positions were exposed about the personal, structural, and cultural influences (Archer, 2012 ; Ryan, 2014 ) on teaching creative writing. These include limited teacher and student knowledge of what constitutes creative writing (Personal Emergent Properties [PEPs]), and no shared understanding or expectation in relation to creative writing pedagogy in their context (Cultural Emergent Properties [CEPs]). The negative impact of standardised testing and trending approaches on how teachers teach writing (CEP; Structural Emergent Properties [SEPs]) could also be considered (see AUTHORS 1 and 3, 2014 for example). In addition, teachers’ poor self-efficacy in terms of teaching creative writing (PEP); a paucity of quality professional development about teaching and assessing creative writing (SEP); and issues related to the sustainability of creative approaches to teach writing (SEP; CEP) need to be considered by leaders and teachers in schools. Our literature review advances knowledge about creative writing by revealing two interconnected areas that affect creative writing practices. Findings suggest that a parallel focus on personal conditions and contextual conditions—including structural and cultural—has the potential to improve creative writing in general. Below, we share some implications and recommendations for improved practice by focussing on both (1) personal views about creative writing and (2) the structural and cultural aspects that affect creative writing practices at schools.

Focussing on personal views about creative writing

School leaders and teachers must clearly define what creative writing is, what key skills constitute creative writing.

From our search it was apparent that schools and their educators often do not have a clear idea or indeed a shared idea as to what constitutes creative writing in relation to their own context. Without a well-defined focus for creative writing students may find it difficult to know what is required in classroom tasks and assessment. In addition, when planning for creative writing in school programs, teachers should consider flexible learning opportunities and choice for their students when developing their creative writing skills. Such flexibility should also involve choice of topic, ways of working (e.g. peer collaboration, individual activities etc.), and open discussions led by students in the classroom as shown throughout this paper. It would also be important for leaders and teachers to interrogate current approaches to teaching writing which we argued in the introduction to be formulaic and genre based.

Improve teacher self-efficacy, confidence, and content knowledge in teaching writing

Many of our studies showed that teachers who lacked confidence about writing themselves had less knowledge and skills to teach writing than those that may have participated in projects encouraging ‘teachers as writers’. Further, improved knowledge of grammar (as highlighted in Macken-Horarik’s, 2012 work); talk about writing in the classroom and other spaces (Cremin et al., 2020 ) and the writing process (see Ryan, 2014 ) could assist teachers in becoming more confident to take risks in the classroom with their students. Above all being playful about writing through extended conversations and practices is required.

Focussing on the structural and cultural resources

Improve training and further professional development and learning about teaching and assessing creative writing.