An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice toward Food Poisoning among Food Handlers and Dietetic Students in a Public University in Malaysia

Aimi m mohd yusof, nor a a rahman, mainul haque.

- Author information

- Copyright and License information

Address for correspondence: Dr. Mainul Haque, Faculty of Medicine and Defence Health, Universiti Pertahanan Nasional Malaysia (National Defence University of Malaysia), Kem Perdana Sungai Besi, 57000, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. E-mail: [email protected]

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

Background:

Food poisoning (FP) commonly occurs because of consuming contaminated food, which can be fatal. Many people are not aware of the dangers of FP. Thus, the purpose of this study is to analyze the knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) of FP among dietetic students (DS) and food handlers (FH) in a public university in Malaysia.

Materials and Methods:

A cross-sectional study was designed, and a self-administered questionnaire was distributed to 106 respondents. The survey comprised four sections including sociodemographic, knowledge, attitude, and practice.

Total percentage scores for KAP for FH were 86.06%, 32.40%, and 19.91%, respectively, whereas the KAP scores for DS were 89.36%, 34.26%, and 19.94%, respectively. This study revealed that the respondents had good knowledge but poor attitude and practice toward FP. Total mean percentage of KAP scores for DS was higher than FH. Besides, no significant difference was observed in KAP toward FP across different genders, age, education, and income levels among FH. However, for DS, significant difference ( p = 0.008) was observed in knowledge toward FP between genders. Significant association ( p = 0.048) was also reported in practice toward FP with age among DS. This study also found a significant association between knowledge and attitude ( p = 0.032) and knowledge and practice ( p = 0.017) toward FP among FH.

Conclusion:

Nevertheless, among DS, no significant association was observed between knowledge, attitude and practice toward FP. The findings may help them to plan effective methods to promote better understanding about FP and improving their knowledge and awareness.

K EYWORDS : Knowledge and practice , food poisoning , dietetic students , food handlers

I NTRODUCTION

Food poisoning (FP) refers to a group of illnesses that result from the ingestion of contaminated food that contains infectious organisms.[ 1 ] FP is defined as “illnesses caused by bacteria or other toxins in food, typically with vomiting and diarrhea.”[ 2 ] It was estimated that 76 million illnesses because of foodborne diseases resulted in 325,000 hospitalizations and 5,000 deaths each year in the USA.[ 3 ] Similarly, 1.3 million cases of foodborne illnesses, 21,000 hospitalizations, and 500 deaths were reported in England and Wales yearly.[ 4 ] The incidence of foodborne diseases was reported as 47.79 per 100,000 population in Malaysia in 2009, but had 32% increase in 2010, which is after only one year lapse.[ 5 ] Three deaths had been reported in Malaysia after consuming food served at a wedding ceremony in 2013.[ 6 ] Multiple causes are reported that lead to FP of which the most important is incorrect food safety practices. Most cases of FP were due to poor hygiene practices and usually occur in the school canteens, hostel kitchens, restaurants, and stall markets.[ 7 ]

This study was explicitly conducted among food handlers (FH) and dietetic students (DS) in a public university in Malaysia. The main reason for choosing these two groups was that DS were supposed to be more aware toward FP as they learnt about food safety and nutritional facts, whereas FH should also be mindful regarding this issue. This study also aims to find out the association between sociodemographic data with knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) toward FP among DS and FH.

M ATERIALS AND M ETHODS

Study area : This study was carried out in a public university in Malaysia.

Sampling population : This survey involved DS from Year I to IV and FH from the cafeterias in the university campus.

Study design : A cross-sectional study was designed and carried out, which involved the distribution of self-administered questionnaire to DS and FH in the university campus.

Study period : Data were collected from February 17, 2016, to February 26, 2016.

Sampling method

The study respondents were selected by quota sampling where convenient sampling was carried in the groups of DS and FH.

Inclusion criteria

Volunteered to participate in this study

Understood either English or Malay as the questionnaires provided were in these two languages

Aged 18 years or above

Sample size : The sample size ( n ) was 106, calculated using the single proportion formula [ n = ( Z α/2 /Δ)2 p (1 – p )] using Z α/2 = 1.96 for 95% confidence interval, p = 0.50 as proportion in population,[ 8 ] and precision, Δ = 0.10, with the addition of 10% nonresponse rate.

Data collection

The survey was conducted by distributing the self-administered questionnaire to the respondents. Before that, detail briefing was given to them so that they understood the purpose of this study. The data were collected among DS and FH in the public university. The questionnaire contained four sections, section A, B, C, and D, which were sociodemographic, knowledge, attitude, and practice toward FP, respectively. Each section consisted of 15 questions. Section A was designed to determine the sociodemographic information of the respondents, which included age, level of education, sex, and income. Section B contained two parts, the answer choices for part 1 were “yes,” “no,” and “I do not know,” whereas for part 2, they were “true,” “false,” and “not sure.” For section C, “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree” (Likert scale) were the answer choices for attitude, whereas for section D, “never” to “always” were the answer choices. In this questionnaire, the respondents needed to tick the appropriate answer choices. All items were modified from previous studies.[ 7 , 8 ] The questionnaire was validated through two approaches, which were content validity and face validity. The content validity of the questionnaire was validated by experts in this field, whereas face validity was conducted through a pilot study.

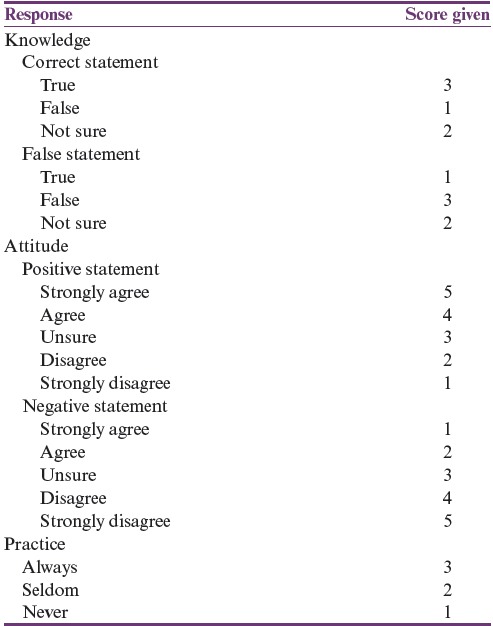

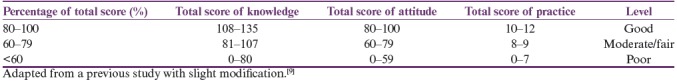

Scoring system

The scoring system for KAP toward FP is shown in Table 1 , whereas the grading of the total scores for the levels of KAP is shown in Table 2 .

Scoring system for knowledge, attitude, and practice

Grading of the total scores for the level of knowledge, attitude, and practice toward food poisoning

Data analysis

Data collected from the questionnaires were analyzed using the SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Scieces) 21, IBM, Armonk, NY, United States of America. Comparison of mean total scores of KAP between two independent groups was analyzed using independent t -test, whereas analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for the comparison between more than two independent groups after checking for the relevant assumptions of the tests. Association between numerical variables was analyzed using Pearson correlation where the assumptions were satisfied, or otherwise Spearman correlation test was used.

Ethical approval

The study approval was obtained from the university’s postgraduate and research committee (Memo No. IIUM/310/G/13/4/4–179, February 1, 2016). Each respondent’s personal information was confidential, and study participation was voluntary. The study population was informed about the objectives and processes of the study where the data gathered would be anonymized, including for publication. Written consent was then obtained before the questionnaires were distributed.

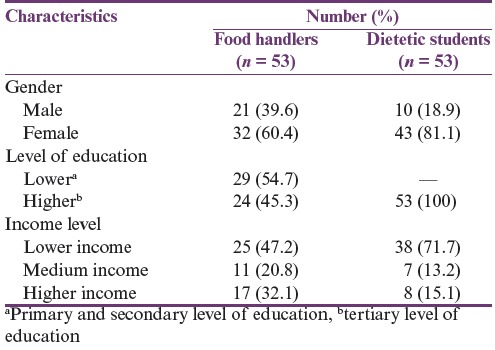

Sociodemographic characteristic of the respondents

In this KAP study, 106 respondents participated involving FH ( n = 53) and DS ( n = 53). The sociodemographic characteristics include age, gender, occupation, and level of education and income. Female respondents were more than male respondents for both the groups [ Table 3 ]. The respondents’ age involved in this study was 18–51 years, and the mean age was 27.14 (standard deviation [SD] = 7.21) years. The details of sociodemographic data are shown in Table 3 .

Sociodemographic data of the respondents ( n = 106)

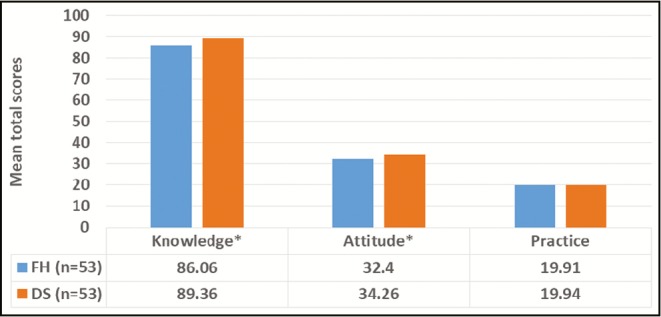

Scores for knowledge, attitude, and practice toward food poisoning

The total percentage scores for KAP for FH were 86.06%, 32.40%, and 19.91%, respectively, whereas the KAP scores for DS were 89.36%, 34.26%, and 19.94%, respectively. According to the classifications in Table 2 , the respondents had good knowledge but poor attitude and practice toward FP. Generally, the total KAP percentage score for FH was lower than that for DS.

Knowledge toward food poisoning

Most of the respondents (FH = 98.1%, DS = 100%) had heard about FP. Again, most of the respondents (89.6%) knew that FP can lead to death. In addition, 77.4% (41) and 90.6% (48) of FH and DS, respectively, knew the causes of FP. The correct answers for the causes of FP are Salmonella, Staphylococcus aureus , and Listeria spp. In this part, 52.8% of FH and 98.1% of DS identified Salmonella as the cause of FP. Both groups showed positive answers in identifying raw egg (FH = 52.8%, DS = 94.3%), raw milk (FH = 62.3%, DS = 77.4%), and sushi (FH = 30.2%, DS = 62.3%) as the causes of FP. Unfortunately, more than one-third of FH opined that sushi could not cause FP. A total of 58.5% and 98.1% of FH and DS, respectively, answered correctly as Escherichia coli to be associated with FP with raw and undercooked meat. The respondents also identified Campylobacter (FH = 50.9%, DS = 47.2%) as the cause of FP with raw or undercooked poultry. For the next statement, respondents needed to choose the correct symptoms of FP, which were vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal cramp. All DS and more than 90% of FH answered correctly regarding the symptoms of vomiting and diarrhea for FP, whereas, regarding abdominal cramp, only 88.7% of FH and 79.2% of DS answered correctly. Approximately half of the respondents knew that the slices of honeydew, baked potato, leftover turkey, and chocolate cake kept overnight on the counter and eaten as it is can cause FP. The last question regarding the suitable temperature (74°C) of heating of leftover food was answered precisely by 37.7% and 50.9% of FH and DS, respectively.

Attitude toward food poisoning

Among the respondents, 52.8% FH and 79.3% DS “disagree” to drink raw milk rather than pasteurized milk. In addition, only 30.2% FH and 11.3% DS “disagree” that it is safe to eat fresh raw milk and cheese. On the other hand, 86.8% FH and 92.5% DS “agree” with the statement that they prefer cutting their nails regularly because long nails could contaminate food. Approximately 77.4% of both groups “agree” that wearing gloves is important during the preparation of food. Next, 51% FH and 83% DS respondents “disagree” that half-cooked meat is safe to be eaten. Only 15.1% (8) but 90.5% (48) of FH and DS, respectively, “disagree” that drinking milk from a dented can is safe. Meanwhile, 84.9% (45) and 90.6% (48) of FH and DS, respectively, “disagree” to eating in unclean cafeteria. On next question, 45.3% (24) and 71.7% (38) of FH and DS “agree” that all of us can be a source of FP. Finally, 34% (18) and 66% (35) of FH and DS “disagree” that wiping off the cutting board with a clean paper towel is enough to prevent the spreading of foodborne pathogens.

Practice toward prevention of food poisoning

Among the respondents, 67.9% (36) and 81.1% (43) of FH and DS, respectively, always checked the expiry date before buying foods, whereas 67.9% (36) and 79.2% (42) of FH and DS, respectively, always washed the cutting board before use. On the other hand, 86.8% (46) and 52.8% (28) of FH and DS, respectively, always washed their hands with water and soap after using the toilet. Subsequently, 24.5% (13) and 15.1% (8) of FH and DS, respectively, never kept cooked meat or chicken for more than 4 h at room temperature. Again, 60.4% (32) and 5.7% (3) of FH and DS, respectively, never allow their fingernails to grow long. Finally, 88.7% (47) and 90.6% (48) of FH and DS, respectively, always practiced washing fresh vegetables or fruits before eating.

Association of sociodemographic characteristics with knowledge, attitude, and practice toward food poisoning

Comparing knowledge, attitude, and practice toward food poisoning between food handlers and dietetic students.

Figure 1 shows the comparison of mean total scores of KAP toward FP among FH and DS in the study. DS showed significantly higher mean total percentage score in knowledge ( p = 0.004) and attitude ( p = 0.010) as compared to FH, but the difference was not significant for practice scores.

Comparing mean total scores of knowledge, attitude, and practice toward food poisoning between food handlers (FH) and dietetic students (DS). *Significant difference using independent t -test ( p -values of knowledge = 0.004 and attitude = 0.010)

Factors associated with knowledge, attitude, and practice toward food poisoning among food handlers and dietetic students

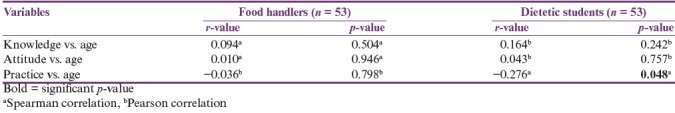

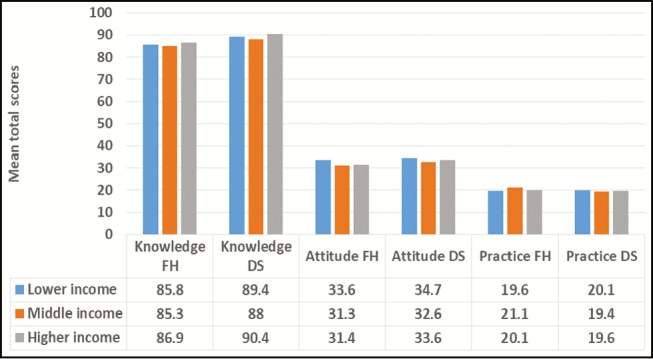

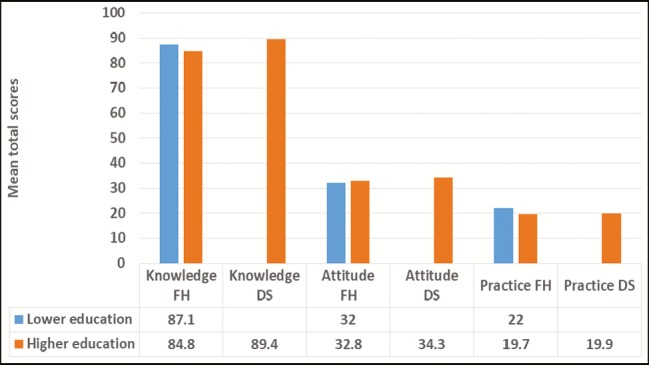

As shown in Table 4 , no significant association was observed between the total scores of KAP toward FP with age among FH and DS, except for between practice and age among DS ( r = −0.276; p = 0.048). The result indicates negative, fair, or little correlation between the variables, meaning the total scores of practice toward FP was lower with older age of DS. On the other hand, comparisons of KAP total scores between different genders, levels of education, and income among FH and DS are shown in Figures 2 – 4 , respectively, with no significant difference found except for the comparison of knowledge between male and female among DS ( p = 0.008) with male DS showing higher scores as compared to female DS.

Correlation between total scores of knowledge, attitude, and practice toward food poisoning with age among food handlers and dietetic students

Comparing mean total scores of knowledge, attitude, and practice toward food poisoning between different genders among food handlers (FH), n (male) = 21; n (female) =32 and dietetic students (DS), n (male) = 10; n (female) = 43. *Significant difference using independent t-test ( p = 0.008)

Comparing mean total scores of knowledge, attitude, and practice toward food poisoning between different levels of education among food handlers (FH), n (male) = 21; n (female) = 32. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) test carried out found no significant difference for any of the variables

Comparing mean total scores of knowledge, attitude, and practice toward food poisoning between different levels of education among food handlers (FH), n (male) = 21; n (female) = 32. Comparison cannot be made between levels of education among dietetic students (DS), n = 53, because all of them came from the same level of higher education. Independent t -test performed found no significant difference for any of the variables

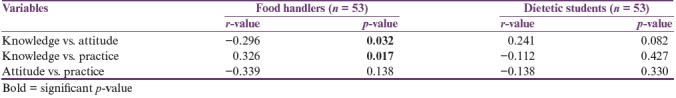

Correlation between knowledge, attitude, and practice toward food poisoning

A significant association ( r = −0.296, p = 0.032) was observed between knowledge and attitude toward FP among FH, also between knowledge and practice ( r = 0.326, p = 0.017) [ Table 5 ]. However, no significant association was observed between attitude and practice among FH, neither was any significant association detected between knowledge, attitude, and practice among DS [ Table 5 ].

Association between total scores of knowledge, attitude, and practice toward food poisoning using Pearson correlation test among food handlers and dietetic students

D ISCUSSION

According to the World Health Organization, 700,000 Asians die each year because of FP.[ 10 ] Hence, it is essential to possess good KAP toward the illness. The respondents in this study had good knowledge but poor attitude and practice toward FP. The total mean KAP score for DS was higher than that for FH.

Sociodemographic characteristics of respondents

A total number of 106 respondents were involved in this study, which consisted of 53 DS and 53 FH. In this study, female respondents outnumbered male respondents. The possible explanation could be that female respondents were more interested toward the dietetic field and worked in the kitchen as FH. The mean age was 27.14 (SD = 7.21) years. In terms of income, most of DS fall in low-income category. Students’ scholarship amount was considered in that category.

The mean percentage knowledge score for DS is higher than that for FH. This correlates with correct answers given by most of DS regarding knowledge about FP. Among the three components, knowledge had the highest percentage score. DS had higher knowledge regarding FP as compared to FH. Both groups were aware that FP could lead to death. Majority of DS knew the cause of FP but more than half of FH were not sure. One study revealed that health science discipline scored higher in food safety knowledge.[ 11 ] DS scored higher because they studied about food safety education.[ 12 ] In addition, both groups answered sushi could cause FP. It has been reported that sushi can promote FP and hepatitis B.[ 13 ] Thus, ensuring the cleanliness and food safety in common dining places in students’ hostels, in cafe and restaurants should be considered as an important public health action.[ 14 ]

The most common pathogens involved in FP are Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Salmonella, Listeria spp., Campylobacter , and Clostridium perfringens .[ 15 ] DS had better knowledge regarding this as compared to FH as more than 50% of DS answered correctly. However, more than 18% of both categories of respondents were unsure regarding Legionella , which is consistent to an earlier study.[ 16 ] Legionella is a microorganism, which is actually often responsible for severe pneumonia.[ 17 ] Nevertheless, many of the respondents managed to answer correctly regarding the symptoms of FP, and this is consistent with an earlier finding.[ 15 ] Leftover food should be heated to 74°C to prevent FP. DS scored higher on this matter as 50.9% of them answered correctly, whereas in FH, only 37.7% answered correctly. Moreover, according to the Malaysian Ministry of Health, leftover food should be reheated at least at 74°C to prevent FP.[ 5 ] On the other hand, a previous study reported that FH had a high score in knowledge regarding food temperature control.[ 18 ] This study findings were similar to an earlier study in Turkey where FH had a low score in food temperature control.[ 19 ]

Although the mean percentage attitude scores of DS were higher than FH, the scores indicated that the respondents of both categories had poor attitude toward FP. This finding is similar to a previous study where the mean percentage of attitude scores were poor.[ 8 ] However, both groups “disagree” to drink raw milk rather than pasteurized milk, though this result is not supported by another previous study, which mentioned that the farmer believed that the raw milk is healthier than pasteurized milk.[ 20 ]

It has been reported that most of FH gave the correct statement that the consumption of raw milk and cheese could increase the risk of FP.[ 21 ] Nevertheless, more than half of DS in this study opined that eating raw milk and cheese is safe. This result is similar to another study, which similarly reported that eating raw milk and cheese is safe.[ 8 ] Furthermore, the majority of FH showed a negative attitude toward hygienic statement as compared to DS. This finding was supported by earlier research findings, which reported that more than 50% of FH showed negative attitude in terms of hygiene.[ 22 ] This study also found that FH showed a negative attitude toward the prevention of FP as majority “agree” that washing hand with water only to prevent FP as opposed to washing hand with water and soap. It has been advocated that proper hand washing is essential especially among retail FH to ensure a good standard of food safety and to avoid FP.[ 23 , 24 , 25 ] Besides, most DS opined that drinking from a dented can is harmful, whereas only a minor portion of FH agreed with the earlier notion. This denotes that FH has a negative attitude in preventing FP. This is one of the important facts that FH need to know as they prepare food and drinks for the customer. Drinking from a dented container can lead to a considerable dangerous health hazard.[ 26 ]

It can be considered from the mean percentage practice score that both groups had a poor practice of food hygiene. However, an earlier study revealed that FH showed a positive attitude, which was different from this study.[ 18 ] A few other studies also revealed that FH had a high mean score in hygiene practice and achieved an acceptable level.[ 27 , 28 ] However, an overseas study found that FH showed poor practice of strict food hygiene strategies toward prevention of FP.[ 29 ] On the other hand, it has been reported that food exposed at room temperature for 4 h or more are not safe to be eaten.[ 30 ]

Association between sociodemographic factors with knowledge, attitude, and practice toward food poisoning

In terms of knowledge toward FP, DS scored significantly higher than FH. This could be because DS had a higher education level as compared to FH. This statement is supported by earlier research findings mentioning that those who have high education level tend to have a high mean score in knowledge.[ 17 ] This study also found a significant difference in terms of knowledge toward FP between male and female respondents among DS. The finding denotes that male respondents have higher knowledge level regarding FP as compared to female respondents. This result was different and opposite to another study, which revealed that female students have a high mean score in terms of knowledge.[ 11 ] Furthermore, this study also revealed a significant difference of total attitude toward FP between FH and DS, besides a significant association between the total scores of practice and age among DS. A study found no significant relationship between gender and practice toward FP among FH, which is similar to the findings in this study.[ 22 ]

The results obtained showed a negative correlation between knowledge and attitude among FH. FH in this study showed high scores in knowledge but tend to have negative attitude toward FP. However, a previous study reported a positive correlation between knowledge and attitude among FH.[ 31 ] It has been mentioned that knowledge helps to improve attitude.[ 32 ]

Also, negative correlation was observed between knowledge and practice among DS and attitude and practice among both respondent groups, but the correlation was not statistically significant. These findings were similar to a previous research report, which found negative correlation between attitude and practice among FH.[ 31 ] Another study revealed that having good knowledge and attitude will lead to good practice measures among FH.[ 22 ] However, the results of this study revealed that having good knowledge and attitude does not lead to good practice as reported in a Turkish study.[ 19 ]

Also, a significant association was observed between knowledge and practice toward FP among FH. The r value showed little positive correlation, which means that knowledge leads to positive practice. Nevertheless, another research revealed a negative correlation between knowledge and practice among FH.[ 31 ] However, in this study, a negative correlation was observed between total knowledge and practice among DS, though it was not statistically significant. Finally, no significant association was reported between practice and attitude of FP for both groups. This is a cross-sectional study with its inherent limitation. Moreover, it is a single-center research with limited study because of financial and time constraints.

C ONCLUSION

In conclusion, this study shows that FH and DS had good knowledge but poor attitude and practice, though the total mean percentage score of KAP for DS was higher than that for FH. Besides, no significant difference was observed in KAP toward FP across different genders, age, education, and income levels among FH. However, DS possess significant differences in knowledge toward FP between genders. Also, a significant association was observed between practices toward FP with age among DS. This study also found a significant association between knowledge and attitude and knowledge and practice regarding FP among FH. Nevertheless, among DS, no significant association was observed between knowledge, attitude, and practice toward FP.

Financial support and sponsorship

Conflicts of interest.

There are no conflicts of interest.

R EFERENCES

- 1. Al-Mazrou YY. Food poisoning in Saudi Arabia. Potential for prevention? Saudi Med J. 2004;25:11–4. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Hormny AS. Oxford advance learner's dictionary of current English. 7th ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2007. [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Mead PS, Slutsker L, Dietz V, McCaig LF, Bresee JS, Shapiro C, et al. Food-related illness and death in the United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 1999;5:607–25. doi: 10.3201/eid0505.990502. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Adak GK, Long SM, O’Brien SJ. Trends in indigenous foodborne disease and deaths, England and Wales: 1992 to 2000. Gut. 2002;51:832–41. doi: 10.1136/gut.51.6.832. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Ministry of Health. Annual Reports. Planning division health informatics center, Ministry of Health, Malaysia. 2014. [Last accessed on 2015 Nov 12]. Available from: http://www.health.gov.bt/publications/annualreports/

- 6. Ramli S, Rattanachot O, Sahir SFM, Osman AR. Tiga Maut Keracunan Makanan, Utusan Malaysia. 2013. [Last accessed on 2018 Oct 9]. Available from: http://www.utusan.com.my/utusan/Jenayah/20131001/je_01/Tiga-maut-keracunanmakanan .

- 7. Norazmir MN, Norazlanshah H, Naqieyah N, Anuar MIK. Understanding and use of food package nutrition label among educated young adults. Food Control. 2012;11:934–40. [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Sharif L, Al-Malki T. Knowledge, attitude and practice of Taif University students on food poisoning. Food Control. 2010;21:55–60. [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Tikuye A. South Africa: University of South Africa; 2013. [Last accessed on 2018 Oct 9]. Knowledge, attitude, and practices of health care providers towards isoniazide preventive therapy (IPT) provision in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia [dissertation] Available from: http://uir.unisa.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10500/11916/dissertation_tikuye_am.pdf;sequence=1 . [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. World Health Organization. Food safety: resolution of the executive board of the WHO, 105th Session, EB105. R16 28, Agenda item 3.1. 2000. [Last accessed on 2018 July 16]. Available from: http://apps.who.int/gb/archive/pdf_files/EB105/eer16.pdf .

- 11. Unklesbay N, Sneed J, Toma R. College students’ attitudes, practices, and knowledge of food safety. J Food Prot. 1998;61:1175–80. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-61.9.1175. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Scheule B. A comparison of the food safety knowledge and attitudes of hospitality and dietetic students. J Hosp Tour Educ. 2002;14:42–50. [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Ng W-M. Popularization and localization of sushi in Singapore: an ethnographic survey. New Zealand J Asian Stud. 2001;3:7–19. [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Kwon J, Roberts KR, Sauer K, Cole KB, Shanklin CW. Food safety risks in restaurants and school foodservice establishments: health inspection reports. [Last accessed on 2018 July 15];Food Prot Trends. 2014 34:25–35. Available from: http://www.foodprotection.org/files/food-protection-trends/Jan-Feb-14-kwon.pdf . [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Sharifa Ezat WP, Netty D, Sangaran G. Paper review of factors, surveillance and burden of foodborne disease outbreak in Malaysia. Malay J Public Health Med. 2013;13:98–105. [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Mitchell RE, Fraser AM, Bearon LB. Preventing food-borne illness in food service establishments: broadening the framework for intervention and research on safe food handling behaviors. Int J Environ Health Res. 2007;17:9–24. doi: 10.1080/09603120601124371. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Rathore MH. Legionella infection. Drugs and diseases. Pediatrics: general medicine. 2018. [Last accessed on 2018 July 15]. Available from: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/965492-overview .

- 18. Sharif L, Obaidat MM, Al-Dalalah MR. Food hygiene knowledge, attitudes and practices of the food handlers in the military hospitals. Food Nutr Sci. 2013;4:245–51. [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Bas M, Ersun AS, Kıvanç G. The evaluation of food hygiene knowledge, attitudes, and practices of food handlers’ in food businesses in Turkey. Food Control. 2006;17:317–22. [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Hegarty H, O’Sullivan MB, Buckley J, Foley-Nolan C. Continued raw milk consumption on farms: why? Commun Dis Public Health. 2002;5:151–6. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. Osaili TM, Obeidat BA, Jamous DOA, Bawadi HA. Food safety knowledge and practices among college female students in north of Jordan. Food Control. 2011;22:269–76. [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. Abdul-Mutalib NA, Syafiaz AN, Sakai K, Shirai Y. An overview of foodborne illness and food safety in Malaysia. Int Food Res J. 2015;22:896–901. [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. qFood Standards Australia New Zealand. A guide to the food safety standards. Chapter 3. Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code. 3rd ed. 2016. [Last accessed on 2018 July 15]. Available from: http://www.foodstandards.gov.au/publications/Documents/Safe%20Food%20Australia/FSANZ%20Safe%20Food%20Australia_WEB.pdf .

- 24. Mathur P. Hand hygiene: back to the basics of infection control. Indian J Med Res. 2011;134:611–20. doi: 10.4103/0971-5916.90985. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. Darko S, Mills-Robertson FC, Wireko-Manu FD. Evaluation of some hotel kitchen staff on their knowledge on food safety and kitchen hygiene in the Kumasi Metropolis. Int Food Res J. 2015;22:2664–9. [ Google Scholar ]

- 26. Byrd-Bredbenner C, Abbot JM, Quick V. Food safety knowledge and beliefs of middle school children: implications for food safety educators. J Food Sci Educ. 2010;9:19–30. [ Google Scholar ]

- 27. Saad M, See TP, Adil MAM. Hygiene practices of food handlers at Malaysian government institutions training centers. Proc Soc Behav Sci. 2013;85:118–27. [ Google Scholar ]

- 28. Rodríguez M, Valero A, Posada-Izquierdo GD, Carrasco E, Zurera G. Evaluation of food handler practices and microbiological status of ready-to-eat foods in long-term care facilities in the Andalusia region of Spain. J Food Prot. 2011;74:1504–12. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-10-468. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 29. Akabanda F, Hlortsi EH, Owusu-Kwarteng J. Food safety knowledge, attitudes and practices of institutional food-handlers in Ghana. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:40. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3986-9. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 30. United States Department of Agriculture. Food Safety and Inspection Service. Food Safety Information. How temperatures affect food. 2011. [Last accessed on 2018 July 15]. Available from: https://www.fsis.usda.gov/shared/PDF/How_Temperatures_Affect_Food.pdf .

- 31. Ansari-Lari M, Soodbakhsh S, Lakzadeh L. Knowledge, attitudes and practices of workers on food hygienic practices in meat processing plants in Fars, Iran. Food Control. 2010;21:260–3. [ Google Scholar ]

- 32. Acikel CH, Ogur R, Yaren H, Gocgeldi E, Ucar M, Kir T. The hygiene training of food handlers at a teaching hospital. Food Control. 2008;19:186–90. [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Knowledge, Attitude, Practice and Food Poisoning Associated Factors Among Parents in Bench-Sheko Zone, Southwest Ethiopia

Besufekad mekonnen, nahom solomon, tewodros yosef.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Correspondence: Besufekad Mekonnen Department of Public Health, Mizan-Tepi University, P.O. Box: 260, Mizan-Aman, Southern Nation Nationality and People Region, Ethiopia Email [email protected]

Received 2021 Jan 22; Accepted 2021 Apr 9; Collection date 2021.

This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution – Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/ ). By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms ( https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php ).

Food poisoning is a food borne disease, mainly resulting from ingestion of food that contains a toxin, chemical or infectious microorganisms like bacteria, virus, parasite, or prion. On the other hand, avoiding food contamination during preparing and feeding is a key factor for reducing the prevalence of food poisoning. This study aimed to assess the knowledge, attitude, self-reported practice and food poisoning associated factors among parents in the selected health centers of Bench-Sheko Zone in Ethiopia.

An institution-based cross-sectional study was conducted among 408 systematically selected parents in Bench-Sheko zone, Ethiopia. The data were collected through face to face interview using a structured questionnaire.

The median knowledge score was 8.0 with an interquartile range (IQR) of 8.0–10.0. The median attitude score was 9.0 with an IQR of 6.0–9.0. The median practice score was 12.0 with an IQR of 10.0–13.0. A positive correlation was seen between knowledge and attitudes of parents with food poisoning (r= 0.321, P < 0.026), between knowledge and practices of parents towards food poisoning (r= 0.312, P < 0.001) and between attitude and practices result towards food poisoning (r= 0.224, p < 0.031). The parents with a higher education level, employed and who live in a city were the factors significantly associated with higher knowledge scores ( p < 0.05). The improved attitude was seen as educational level increased ( p <0.05). The parents with female gender, employed and who live in a city were significantly associated with higher hygienic practices towards the prevention of food poisoning ( p <0.05).

The knowledge, attitude, and self-reported practices of parents regarding food poisoning prevention are associated with each other and are affected by socio-demographic variables. Therefore, adequate emphasis should be given by health sectors to designing strong strategies which address the specific contributing factors for the problem.

Keywords: knowledge, attitude, practices, parents, food poisoning, Ethiopia

Introduction

Food is a known vehicle for many pathogenic and toxigenic agents that cause what are known as food-borne diseases. 1 , 2 Food borne diseases (FBDs) are diseases which are caused by the consumption of contaminated foods or water, with a variety of diseases causing agents ranging from infective organisms, poisonous chemicals, radioactive substances and other harmful substances. 1 , 3 FBDs have increased over the years, and treacherously upset the health and economic well-being of many people in developed and developing countries. 3–5

According to World Health Organization (WHO), contaminated food contributes to 1.5 billion cases of diarrhea in children each year, resulting in over three million premature deaths. 6 , 7 Safe food is defined as not causing harm or illness to the consumer. 8 Food safety is the processes of handling, preparing and storing of food in ways that prevent contamination by toxic chemicals 9 or pathogenic microbes, which result in food-borne illness. 1 , 10

Food poisoning occurs as a result of consuming food contaminated with microorganisms or their toxins; the contamination starting from inadequate preservation methods, unhealthy handling practices, cross-contamination from food contact surfaces, or from persons hiding the microorganisms in their nails and on the skin. 11 The presence of poor hygienic practices during food preparation, handling and storage creates the conditions that allow the proliferation and transmission of disease causing organisms such as bacteria, viruses and other food-borne pathogens. 2 , 15 The signs of toxigenic food poisoning mostly appear within 24 hours after eating of contaminated food. The symptoms include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, a headache and fever. The life-threatening neurologic, hepatic and renal syndromes may occur several days after intestinal, and may cause permanent disability or death depending upon which microbe is ingested. 1 , 13–15

The incidence of FBDs depends on the hygienic measures implicated in food production and storage, but they could be ineffective if consumers have unhygienic practices and food handling approaches. 16 It is recommended to apply different precaution techniques to keep safety of foods, including: to wash hands well and often, especially after using the bathroom, before touching food, and after touching raw food by using soap and warm water and scrub for at least 15 seconds; clean all utensils, cutting boards, and surfaces that you use to prepare food with hot, soapy water; wash all raw vegetables and fruits; keep raw foods (especially meat, poultry, and seafood) away from other foods until they are cooked; and cook all food from animal sources to a safe internal temperature. 17 But different studies from Ethiopia have reported that people fail to be concerned of and/or properly apply the prevention techniques. 7 , 17–19

It is known that the KAP of food poisoning are key factors for reducing the prevalence of food-borne diseases in food production and serving area. 7 , 20 In addition, the issue demands more evidence, particularly in southwest Ethiopia. Therefore, this study aimed to assess the knowledge, attitude and self-reported practices related to food poisoning among parents in the selected four health centers of Bench-Sheko zone in southwest Ethiopia. The finding will contribute to devise an intervention of operative, effective and proper health intervention program regarding how to handle food safely and adds evidence in the area of interest.

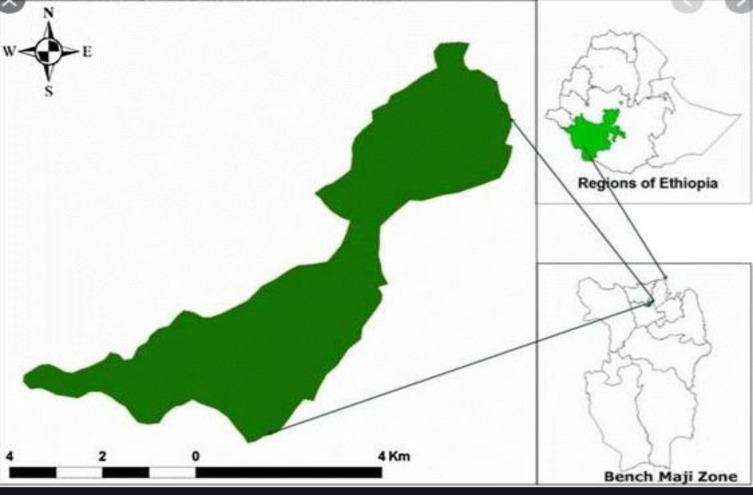

Study Design, Setting and Period

An institution based cross-sectional study was conducted among parents attending health institutions from September 1 to December 30, 2019, in former Bench-Maji zone which is currently named as Bench-Sheko zone, Ethiopia. Bench-Sheko Zone is one of the 16 zones in Southern Nation Nationalities and Peoples Regional state ( Figure 1 ), which is located at 585 km southwest of Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia. The zone has an estimated population of 829,493, and the primary health service coverage of the zone is 92.6%, covering a total catchment area of 19,965.8 km 2 with majority (86%, 713,363.98) of the population living in the rural areas. A study was conducted in four randomly selected primary health centers, namely Bire (found in North Bench district), Kite, Debrework (found in South Bench district) and Biftu (found in Guraferda district).

Map of the study area.

The parents who had children aged less than 6 years old and attending the health centers were selected, interviewed and their responses were recorded. The inclusion criteria were age of 18 years old and above and agreed to participate in the study. Exclusion criteria included parents who were not resident in the study area, had not given birth, who had children over 6 years or who had difficulty in communication.

Sample Size Determination and Sampling Technique

Data collection instrument and procedures.

A structured questionnaire, which was adapted from similar studies, 1 , 21–23 was used. The questionnaire was composed of four parts socio-demographic variables (age, gender, educational status, residency, and number of family members including children, their ages, food preparation habit), food poisoning knowledge related questions including general statements about food poisoning causes (15 questions), food poisoning attitude related questions including statements about eating raw food and washing fruits and vegetables (15 questions), and food poisoning practices related questions regarding eating, drinking and washing hands (20 questions). Moreover, in the knowledge and attitude part, the questionnaire entails five options ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”. In the practice section, the respondents had five choices: “always yes”; “most of the time”; ‘sometimes’; “rarely”; and “always no”.

The data were collected by BSc nurses and public health officers. Two days’ training was given for data collectors and supervisors about objectives of the study, contents of questionnaire, and approaches to interview. A pre-test was conducted on 5% of the sample in other primary health centers than the study set up, and necessary amendment of the questionnaires based on the result of the pre-test were considered. Finally data were collected through a face-to-face interview.

Ethical Consideration

Data collection was started after obtaining permission from Mizan-Tepi University Institutional Review Boards (MTU-IRB). Again, a support letter was obtained from the Bench Sheko Zone Health Bureau. All study participants were informed about the purpose of the study, their right to deny participation, anonymity, and confidentiality of the information. Moreover, the verbal informed consent was approved by the Mizan-Tepi University Ethical Review Board, and this study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data Processing and Analysis

The data were entered in to Epi data manager and analyzed using SPSS software version 22. The descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, median and interquartile range) were conducted to summarize the results. Some characteristics were consolidated into dichotomous (binary) variables for ease of analysis and interpretation. Normality test was made by using Kolmogorov Smirnov test. In addition, the Mann–Whitney U -test and the Kruskal–Wallis H -test were performed to determine significance difference between the mean values. Moreover, Pearson correlation coefficient was designed to examine a possible correlation between continuous variables (knowledge, attitude and practice scores). The level of significance was declared at p value <0.05.

Socio-Demographic Profiles

Of the 422 sampled populations, 408 were interviewed and completed data were collected, giving a response rate of 96.7%. Almost all respondents were women (97.3%). The mean age of the study participants was 32.5 (SD±5.2) years. One hundred sixty-eight (41.2%) of them have achieved secondary educational level followed by 37% of parents who are able to read and write. Again 88% and 74.3% of participants were unemployed and rural residents respectively. Mothers were found to be the responsible body for preparing food for the family (98.8%) ( Table 1 ).

Socio-Demographic Status of Parents in Bench-Sheko Zone, Ethiopia; 2019 (N= 408)

Knowledge About Food Poisoning

The mean value of knowledge about food poisoning was 9±3.2 SD. When the respondents were asked about the highly risky foods for food poisoning, 42% of the study participants responded that eating raw meat is highly risky for food poisoning, 75% responded that eating raw unwashed vegetables is highly risky for food poisoning and 73.4% responded that drinking raw milk is highly risky for food poisoning. Furthermore, 78%, 74%, 75%, 78.4% and 74.5% of the respondents responded correctly that raw white cheese, unwashed not peeled fruits, uncovered leftover cooked food, untreated surface and rainwater, and raw eggs, respectively, were risky food. The majority of respondents (88%) responded that well cooked food is free from microbes that cause food poisoning and that keeping food in refrigerator will slow down the microbial growth and multiplication, so, prevent food poisoning (52%). Nearly half of the respondents (50.9%) said that there is no risk of food poisoning from eating leftover cooked food reserved in refrigerator for 2–3 days. Regarding hygienic condition of parents, 75% of the respondents said that poor hygienic practice of parents could be the source of food poisoning. Instead, only 38.7% of the respondents agreed that some toxins produced by microbes and cause food poisoning are resistant to heating temperature of food.

Attitude Regarding Food Poisoning

The mean value of attitude regarding food poisoning was 8±4.8 SD. Half of the respondents reported that washing hands with soap before preparing (51.2%) and eating food (50.2%), along with thorough washing of vegetables and fruits (50.4%) are necessary to prevent food poisoning. Concerning raw milk, 58.4% of the respondents correctly disagreed that there is no risk of disease from drinking raw cow milk right after milking, 59.7% disagreed that raw milk is more healthy and nutritious than pasteurized or boiled milk. Regarding raw eggs, half of respondents (51.2%) disagreed that raw eggs are more healthy and nutritious than cooked ones, while 22.7% disagreed that there is no risk of disease from drinking raw eggs. Regarding vegetables and fruits, 50.8% of the respondents disagreed that eating vegetation and fruits directly from the plant without wiping has no risk of disease occurrence. Instead, majority of the respondents agreed that baby feces are free from pathogenic microbes if he/she is not sick. Majority of the respondents (74.5%) agreed that rainwater collected in reservoir is safe to drink without any treatment and 49.6% agreed that there is no risk of disease from eating cooked food reserved at room temperature for 1 day if covered.

Practices About Food Poisoning

The mean practice score was 12±4.8 SD. Regarding practices questions, more than half of the respondents wash their hands with soap and water before eating and preparing food, after contact with animals (55.4%) and after using the toilet (55.6%). In addition, 58% of the respondents wash fresh vegetables and fruits before eating while 57.4% wash their hands with water and soap after handling raw unwashed vegetables. Likewise, 54.4% of the respondents may eat fresh vegetables and fruits after just wiping it, without washing it (56.3%) or pick it up from the plants during a field trip and eat it without washing (59.1%). Half of the respondents do not eat raw eggs and 55% of the respondents do not eat raw or half-cooked meat. Moreover, 60% of the respondents drink raw milk. A high percentage of respondents drink from rainwater collected without any treatment (78.4%) and 75% of parents do not eat foods out of their home (hotels, restaurants and cafeteria), 88% of parents may eat raw white cheese prepared from raw unpasteurized milk. Furthermore, 57.4% of the respondents were cooked food left at room temperature for over 6 h without sufficient heating.

The Kruskal–Wallis test was used to assess the association between socio-demographic variables and knowledge. The result revealed that educational level, residency and employment status were significantly associated with knowledge ( P value < 0.05). However, no significant association was seen between age, gender, number of family member, number of children and food preparation habit with knowledge. It is observed that, parents with relatively highest level of education have good level of knowledge about food poisoning. In addition, respondents who live in urban setting have better knowledge than those who live in rural area ( Table 2 ).

Association Between Socio-Demographic Variable and KAP of Food Poisoning, Among Parents in Bench Sheko Zone, 2019

According to Kruskal–Wallis test, there was significant association between gender, educational level and residency with attitude about food poisoning ( p value < 0.005). On the other hand, age, employment status, number of children, number of family, age of the children and food preparation habit did not show any significant association with attitude ( Table 2 ).

It is observed that gender, education and residency had significant association with practices or taking measures against food poisoning. Other socio-demographic variables such as age, employment status, family number, age of children and food preparation habit did not show any significant association with practice of food poisoning. The result revealed that female parents do have better hygiene practice than males. In addition, the respondents with high level of educational status had better hygienic practices than low educational level. Moreover, parents who live in urban area experience better hygienic practices than those who live in rural setting ( Table 2 ).

The Correlations Between Knowledge, Attitude and Practice Towards Food Poisoning

Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used for testing the existence of any correlation between knowledge, attitude and self-reported practices of parents with food poisoning. Accordingly, positive correlation was seen between knowledge and attitudes of parents with food poisoning ( r = 0.321, P value < 0.026). This shows that parents who had good knowledge were more likely to have good attitude regarding food poisoning. In addition, there was positive correlation between knowledge and practices of parents towards food poisoning ( r = 0.312, P value 0.001). This implies that parents who had good knowledge were more likely to have good hygiene practices towards food poisoning. Moreover, there was positive correlation between attitude and self-reported practices result towards food poisoning ( r = 0.224, p value 0.031). It is well expressed that parents who had good attitude were more likely to have good hygiene practices regarding food poisoning.

This study assessed the knowledge, attitude, and self-reported practice and food poisoning associated factors among parents in the selected health centers of Bench-Sheko zone, southwest Ethiopia. In the developing world, females are more commonly responsible for food preparation; the female carries the responsibility for family care as a wife, from cleaning and arranging the house to preparing the food for all members of the family. In addition, the female, as a mother, takes care of her children. 1 , 24 , 25 This is also clearly found in this study where mothers are the responsible body of preparing food, and since mothers have also other house work burdens, there could be gaps in following necessary precautions for keeping safety of food.

Recent studies asserted that knowledge, attitude and practice are key factors in reducing the prevalence of food-borne diseases in food processing and serving area. 1 , 21 , 22 , 26 On the other hand, they themselves are also influenced by many factors including educational status, gender and age of food handlers. 23 , 27–29 In the current study, it is revealed that educational level, residency and employment status were significantly associated with knowledge. Badrie et al 30 and Zyoud et al 1 have also reported similar findings, in which a significant association between educational level and knowledge was scored. Parents with a high level of education reported higher knowledge scores than those with a lower level. In addition, parents who live in the urban setting reported higher scores than those who live in the rural setting. This consistency might be explained by some close features of study population. Parents, who are educated, employed and who live in towns showed higher knowledge scores and attitude is also improved as educational level increased. Parents with female gender, employed and who live in town had higher hygienic practices towards the prevention of food poisoning. Therefore addressing educational gaps and accessing health information to rural community is demanding.

Educational level, gender and residency were also found to have significant influence on attitude about food poisoning. Although gender was found as one factor affecting parents’ attitude regarding food poisoning, opposing result was reported from a study conducted in Palestine, 1 which revealed there was no significant association between gender and attitude regarding food poisoning. Of course, the difference might happen because in our study majority of respondents were women. Again, men in this study area could pass most of their time at field, and/or may contact many people and as a result may have more exposure to information, on the other hand, those who live in towns and/or who had achieved highest level of education may be influenced to experience good attitude. Parents with a high education level reported a good attitude compared to those with a lower level. Zyoud et al, Altekruse et al, and Ozilgen S. have reported comparably close result. 1 , 31 , 32 Again, influence of health information and education status is found to be the most important factor affecting attitude of parents toward food poisoning, so working in filling these gaps would bring better change.

Regarding practice, again gender, level of education and residency were found to have significant association about taking measures against food poisoning. This result is consistent with a study conducted in Debark town and Palestine. 1 , 7 Similarity may be explained by comparability of study population and setting. Parents who live in a town had better hygienic practice than those who live in rural area. In addition, female parents scored higher than males. A possible explanation for this result may be the lack of adequate experience in food preparation between female parents compared to males. Contrary to this, study reports from Henok et al and Zyoud et al 1 , 7 revealed that female parents and village residences lack hygienic knowledge and practices regarding food poisoning. Whenever people live at a distance from towns where many health services and information are easily accessible, it is clear that health problems may occur and failing to keep safety of food is one of the areas which results in big health impact, mainly resulting in food poisoning.

Significant association was also shown between knowledge, attitude and practice. Accordingly; parents who had good knowledge have also demonstrated a good level of attitude and practice. This result is consistent with a study conducted in Iran, Palestine, China and West Indies. 1 , 22 , 30 This implies knowledge is a primary and a very important potential for securing food safety and enabling people to take measures to reduce occurrence of food poisoning, as a result, it demands interventions targeting specific population group so as to empower them to prevent food poisoning.

Generally it is found that knowledge, attitude and practice towards taking measures against food poisoning are still limited and demands efforts to promote public health through applying different health interventions mainly health education targeting the main associated factors.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Two-thirds of the parents have good knowledge about food poisoning but only half of them have good attitude and experience of taking preventive measures to avoid food poisoning. The study also found that gender; educational status, occupation and place of residence were the main factors which showed significant effect and parents who had good knowledge have also demonstrated a good level of attitude and practice. Therefore, emphasis should be given to fill the gaps by applying necessary interventions which consider the major contributing factors as well. Consequently, health sectors in the local area shall give emphasis in fostering knowledge of parents regarding food poisoning and design strategy to change attitude of parents regarding poisoning, facilitate them to experience a good preventive measures and shall promote for good knowledge, attitude and taking preventive measures about food poisoning. Moreover, academic sectors and other sectors working in the area shall design strategies and implement for fostering knowledge, attitude and preventive measures concerning food poisoning and shall make advanced level study of both qualitative and quantitative method to identify the gaps and associated factors more. This study has come with important results but should be used without forgetting its limitation of social desirability bias.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge Mizan Tepi University for unreserved support. In addition, the authors express their appreciation and thanks to Mizan-Tepi University research and community service directorate for overall facilities during the survey. Lastly, the researchers would like to address their deepest thanks to all staff of College of Health Sciences in MTU for their valuable comments.

Funding Statement

The Authors acknowledged Mizan-Tepi University for financial support.

Abbreviations

FBDs, food born diseases; IRB, internal review board; IQR, inter quartile range; KAP, knowledge, attitude and practice; MTU, Mizan-Tepi University; SD, standard deviation; SPSS, Statistical Package for Social Science; WHO, World Health Organization.

Data Sharing Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest for this work.

- 1. Zyoud S, Shalabi J, Imran K, et al. Knowledge, attitude and practices among parents regarding food poisoning: a cross-sectional study from Palestine. BMC Public Health . 2019;19(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-6955-2 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Zeeshan M, Shah H, Durrani Y, Ayub M, Jan Z, Shah M. A questionnaire-based survey on food safety knowledge during food-handling and food preparation practices among university students. J Clin Nutr Diet . 2017;03(02):1–8. doi: 10.4172/2472-1921.100052 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Ulusoy BH, Çolakoğlu N. What do they know about food safety? A questionnaire survey on food safety knowledge of kitchen employees in Istanbul. Food Health . 2018;4(4):283–292. doi: 10.3153/fh18028 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Ismail KA. Assessment of the knowledge, attitude and practice about food safety among Saudi Population in Taif. Biomed J Sci Tech Res . 2018;8(2):4–10. doi: 10.26717/bjstr.2018.08.001629 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Akabanda F, Hlortsi EH, Owusu-Kwarteng J. Food safety knowledge, attitudes and practices of institutional food-handlers in Ghana. BMC Public Health . 2017;17(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3986-9 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Zvenyika F. The knowledge, attitudes and practices, and compliance regarding the basic prerequisite programmes (prps) of food safety management systems of food service workers in boarding schools and restaurants in Masvingo province, Zimbabwe; 2017. (November).

- 7. Dagne H, Raju RP, Andualem Z, Hagos T, Addis K. Food safety practice and its associated factors among mothers in debarq town, Northwest Ethiopia: community-based cross-sectional study. Biomed Res Int . 2019;2019:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2019/1549131 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Mohammed AFH. Food safety knowledge, attitude and self‐reported practices among food handlers in Sohag Governorate, Egypt. East Mediterr Heal J . 2019;25(9):1–5. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Mekonnen B, Siraj J, Negash S. Determination of pesticide residues in food premises using QuECHERS method in Bench-Sheko Zone, Southwest Ethiopia. Biomed Res Int . 2021;2021:1–13. doi: 10.1155/2021/6612096 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Yusuf TA, Chege PM. Awareness of food hygiene practices and practices among street food vendors in Nasarawa State, Nigeria. Int J Health Sci Res . 2019;9(7):156–164. [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Ngoc T, Thanh C. Food safety behavior, attitudes and practices of street food vendors and consumers in Vietnam; 2015.

- 12. Warner K. Street food vending: vendor food safety practices and consumers’ behaviours, attitudes and perceptions; 2013.

- 13. Sharma S, Sangha JK. Relation between food safety awareness and disease incidence: a study of home food preparers in Punjab. Stud Ethnomed . 2015;9(2):255–261. doi: 10.1080/09735070.2015.11905443 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Malavi DN. Food Safety knowledge, attitude and practices of orange-fleshed sweetpotato puree handlers in Kenya. Food Sci Qual Manag . 2017;67(April2018):54–63. [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Oladoyinbo CA, Akinbule OO, Awosika IA. Knowledge of food borne infection and food safety practices among local food handlers in Ijebu-Ode Local Government Area of Ogun State. J Public Health Epidemiol . 2015;7(9):268–273. doi: 10.5897/jphe2015.0758 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. World Health Organization. Five keys to safer food manual safer food manual. Vol 3, 206AD. Available from: http://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/6/11/2833/ . Accessed April21, 2021. [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Eshetu D, Kifle T, Hirigo AT. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of hand washing among aderash primary schoolchildren in Yirgalem Town, Southern Ethiopia. J Multidiscip Healthc . 2020;13:759–768. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S257034 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Adane M, Teka B, Gismu Y, Halefom G, Ademe M. Food hygiene and safety measures among food handlers in street food shops and food establishments of Dessie town, Ethiopia: a community-based cross-sectional study. PLoS One . 2018;13(5):1–13. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0196919 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Tshipamba ME, Lubanza N, Adetunji MC, Mwanza M. Evaluation of the effect of hygiene practices and attitudes on the microbial quality of street vended meats sold in johannesburg, south- africa journal of food: microbiology, safety & hygiene. J Food Microbiol Saf Hyg . 2018;3(2):1–10. doi: 10.4172/2476-2059.1000137 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Adel HS, Ns M, Sm A-R. Assessment of the knowledge, attitude and practice towards food poisoning of food handlers in some Egyptian worksites. Egypt J Occup Med . 2014;38(1):79–94. doi: 10.21608/ejom.2014.789 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. Zolfaghari H, Khezerlou A, Alizadeh-Sani M, Ehsani A. Food-borne diseases knowledge, attitude, and practices of women living in East Azerbaijan, Iran. J Anal Res Clin Med . 2019;7(3):91–99. doi: 10.15171/jarcm.2019.017 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. Henson S, Reardon T. Private agri-food standards: implications for food policy and the agri-food system. Food Policy . 2005;30(3):241–253. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2005.05.002 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. Patil SR, Cates S, Morales R. Consumer food safety knowledge, practices, and demographic differences: findings from a meta-analysis. J Food Prot . 2005;68(9):1884–1894. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-68.9.1884 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. Aa MB. Knowledge, attitude and practice of female teachers regarding safe food handling; is it sufficient? An Intervention Study, Zagazig, Egypt. Egypt J Occup Med . 2017;41(2):271–287. [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. Omar BA, Shadia SM, Anas SD, Mohammed AE. Food hygiene knowledge, attitude and practices among hospital food handlers in Elmanagil City, Sudan. African Journal of Microbiology Research . 2020;14(4):106–111. doi: 10.5897/AJMR2020.9323 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 26. Soon JM, Baines R, Seaman P. Meta-analysis of food safety training on hand hygiene knowledge and attitudes among food handlers. J Food Prot . 2012;75(4):793–804. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-11-502 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 27. Zanin LM, Thimoteo D, Vera V; GeQual Study Group of Food Quality. Centro de Desenvolvimento do Ensino SC. Food Res Int . 2017;100(Pt 1):53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2017.07.042 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 28. Barrie D. The provision of food and catering hospital services in. J Hosp Infect . 1996;33(1):13–33. doi: 10.1016/S0195-6701(96)90026-2 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 29. Badrie N, Gobin A, Dookeran S, Duncan R. Consumer awareness and perception to food safety hazards in Trinidad, West Indies. Food Control . 2006;17(5):370–377. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2005.01.003 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 30. Altekruse SF, Street DA, Fein SB, Levy AS. Consumer knowledge of foodborne microbial hazards and food-handling practices. J Food Prot . 1995;59(3):287–294. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-59.3.287 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 31. Ozilgen S. Food safety education makes the difference: food safety perceptions, knowledge, attitudes and practices among Turkish university students. J Verbr Leb . 2011;6(1):25–34. doi: 10.1007/s00003-010-0593-z [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 32. Ma L, Chen H, Yan H, Wu L, Zhang W. Food safety knowledge, attitudes, and behavior of street food vendors and consumers in Handan, a third tier city in China. BMC Public Health . 2019;19(1):1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7475-9 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (379.9 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 16 May 2019

Knowledge, attitude and practices among parents regarding food poisoning: a cross-sectional study from Palestine

- Sa’ed Zyoud ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7369-2058 1 , 2 ,

- Jawad Shalabi 3 ,

- Kathem Imran 3 ,

- Lina Ayaseh 3 ,

- Nawras Radwany 3 ,

- Ruba Salameh 3 ,

- Zain Sa’dalden 3 ,

- Labib Sharif 4 ,

- Waleed Sweileh 5 ,

- Rahmat Awang 6 &

- Samah Al-Jabi 2

BMC Public Health volume 19 , Article number: 586 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

12k Accesses

24 Citations

Metrics details

Food serves as a vehicle for many pathogenic and toxigenic agents that cause food-borne diseases. Knowledge, attitude, and practices are key factors in reducing the incidence of food-borne diseases in food service areas. The main objective of this study was to evaluate knowledge, attitude, and practices related to food poisoning among parents of children in Nablus, Palestine.

A cross-sectional study was conducted in primary healthcare centers in Nablus district from May to July 2015. Data were collected using structured questionnaire interviews with parents to collect information on food safety knowledge, attitudes, and practices, alongside sociodemographic characteristics.

Four-hundred and twelve parents were interviewed, 92.7% were mothers. The median knowledge score was 12.0 with an interquartile range (IQR) of 11.0–14.0. The median attitude score was 11.0 with IQR of 10.0–13.0, while the median practice score was 18.0 with IQR of 16.0–19.0. Significant modest positive correlations were found between respondents’ knowledge and attitude scores regarding food poisoning ( r = 0.24, p < 0.001), knowledge and practice scores regarding food poisoning ( r = 0.23, p < 0.001), and attitude and practice scores regarding food poisoning ( r = 0.30, p < 0.001). Respondents with a higher education level and who live in a city were the only factors significantly associated with higher knowledge scores ( p < 0.05). Attitude improved as educational level increased ( p < 0.05) and income level increased ( p < 0.05). Those of female gender and employed were statistically significantly associated with higher satisfactory hygienic practices in relation to the prevention of food poisoning ( p < 0.05).

Conclusions

Knowledge, attitude, and practices regarding food poisoning prevention are associated with each other and are affected by a complex interplay between socio-economic variables. The study highlights the need for health education programmes and general awareness campaigns that intend not only to enhance knowledge but also promote parents to practice food safety measures strictly and further strengthen their awareness level.

Peer Review reports

Food serves as a vehicle for many pathogenic and toxigenic agents that cause what are known as food-borne diseases or food poisoning [ 1 ]. In recent decades, food poisoning has become a growing public health problem worldwide, in both developed and developing countries [ 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 ]. It is defined as a variety of illnesses acquired by consumption of contaminated foods or water, with a variety of causes ranging from infective organisms (bacteria and viruses), poisonous chemicals, radioactive substances and other harmful substances leading to more than 250 different food-borne diseases (ranging from diarrhoea to cancers) [ 7 ]. Food safety refers to the processes of handling, preparing and storing of food in ways that prevent contamination by toxic chemicals or pathogenic microbes resulting in food-borne illness [ 8 ].

Symptoms of toxigenic food poisoning mostly appear within 24 h after ingestion of contaminated food while foodborne infections may not appear until 2–3 days later. Symptoms can include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain (which is severe in inflammatory processes), headache and fever. Life-threatening neurologic, hepatic and renal syndromes may occur several days after intestinal symptoms, and may cause permanent disability or death depending upon which microbe is ingested [ 1 , 9 ].

In developing countries, many poisoning cases are due to the consumption of unhygienic foods, pesticide residues in foods or water, and inappropriate food storage conditions. However, food poisoning is not a distinctive phenomenon of these countries only, as it also involves developed countries, due to the increasing demand for low-priced food and lack of ability to provide optimal care under hygienic conditions while preparing and storing food [ 5 , 10 ].

The incidence of food-borne illness depends on the hygienic measures implicated in food production and storage, but they could be ineffective if consumers have poor hygienic practices and food handling approaches [ 11 ]. Approximately 50% of food-borne illness cases are related to improper storage or reheating, with 45% associated with inappropriate food storage and 39% with cross contamination [ 12 ]. Knowledge, attitude and practice are key factors in reducing the incidence of food-borne diseases in foodservice areas [ 13 ]. They are also influenced by various factors like gender (females have a higher level of information than males), age (people younger than 35 years of age need extra food safety education), income level and cultural factors [ 14 , 15 ]. Therefore, evaluation of the baseline of such data (before any food safety education material can be prepared for their use) is an essential first step to inform the development of effective and relevant health education programmers to ensure that food handlers are knowledgeable about and experienced in food safety [ 16 , 17 ].

To the best of our knowledge, there are few studies conducted in Palestine regarding food poisoning or food-borne illnesses [ 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 ]. Therefore, the main objective of this study was to evaluate knowledge, attitude and practices related to food poisoning among parents in Nablus district, Palestine. However, regarding parents’ practices and knowledge regarding food poisoning in Palestine, our study may be the first one conducted in Palestine.

Study design and sampling strategy

In the current study, a descriptive cross-sectional method was applied. The study was conducted in four primary healthcare centres in Nablus, Palestine: Al-Makhfeyah; Ras-Alain; Al-Wosta; and Balata. Parents attending the centers with children aged less than 6 years were interviewed and their answers were transcribed.

A non-probability convenience sampling technique was used. A sample of 104 parents was selected from each primary healthcare centre. Inclusion criteria included parents 18 years old or older and gave consent to take part in the study. Exclusion criteria included parents who were not resident in the study area or had not given birth or who had children over 6 years or who had difficulty in communication.

Data collection form

A questionnaire in the native Arabic language adapted from a previous study [ 23 ] was used. The questionnaire consisted of four sections (see Additional file 1 ):

The first section included demographic information such as participants’ age, gender, educational level, employment status, residency, income level, number of family members including children, their ages, food preparation, and number of meals consumed away from home.

The second section consisted of 15 questions about food poisoning knowledge including general statements about food poisoning causes.

The third section consisted of 15 questions about food poisoning attitude including statements about eating raw food and washing fruits and vegetables.

In the fourth section, consisted of 20 questions about food poisoning practices regarding eating, drinking and washing hands.

In the knowledge and attitude section, the questionnaire provided five choices ranging from ‘strongly agree’ to ‘strongly disagree’. In the practice section, the respondents had five options: ‘always yes’; ‘most of the time’; ‘sometimes’; ‘rarely’; and ‘always no’. The questionnaire was tested with a pilot sample ( N = 30) before conducting the study and no changes were recommended. Permission to use this instrument to measure parents’ knowledge, attitude and practices regarding food poisoning in this study was obtained from the developers of the questionnaire [ 23 ].

Data collection procedure

Clinical pharmacists, who were well-trained on collecting data for the knowledge, attitude and practices questionnaire, carried out data collection. Parents were asked to complete the questionnaire during a face-to-face interview. Each questionnaire took 10–15 min to administer. Statements in the questionnaire were explained when necessary. A verbal consent form, explaining the purpose of the research and assuring confidentiality was read to participants. The participants had the right to participate or not. The data were collected on weekdays only. The collection process occurred from May to July 2015.

Ethical consideration

The Institutional Review Boards (IRB) of An-Najah National University authorized all aspects of the study protocol before the initiation of the study and approval to conduct the study was obtained from the Ministry of Health. Verbal consent was also obtained from all parents before participation.

Data statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS statistics, version 20.0. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the sample. The responses were analyzed as correct or incorrect answers (see Additional file 2 ). Each correct answer was given one point while each incorrect answer was given zero point. Regarding knowledge, the five choices that ranged from ‘strongly agree’ to ‘strongly disagree’ were given values of 4 to 0, respectively. A correct answer indicated good knowledge, whereas an incorrect answer indicated poor knowledge. For attitude, this section included a set of negative statements (1–11) and the other four statements were positive (12–15). Negative statement choices had a value of 0 for ‘strongly agree’ and 4 for ‘strongly disagree’ and for positive statements it was the opposite (4 for ‘strongly agree’ and 0 for ‘strongly disagree’). A correct answer indicated a good attitude and an incorrect answer indicated a poor attitude. The practice section included six positive questions (1–6) with an answer choice value of 4 for ‘always yes’ and 0 for ‘always no’. The remaining questions (7–20) were negative with an answer choice value of 0 for ‘always yes’ and 4 for ‘always no’. A correct answer was indicated hygienic practice and a negative answer indicated unhygienic practice. Responses were consolidated into dichotomous (binary) variables for analysis. Previous studies had shown that consolidating a Likert scale to binary formats does not affect the results [ 24 , 25 ]. Data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range (IQR) for numerical variables, and frequencies with percentages for nominal variables. All scores were tested for normality using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Because the normality of all scores were not met, the Mann-Whitney U test and the Kruskal-Wallis H test were performed. The Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated to examine a possible correlation between continuous variables (knowledge, attitude and practices scores). In all analyses, a significance level of 5% was used.

Sociodemographic data