PhD students’ mental health is poor and the pandemic made it worse – but there are coping strategies that can help

Senior Lecturer in Technology Enhanced Learning, The Open University

Assistant Professor in Strategy and Entrepreneurship, UCL

Disclosure statement

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

University College London and The Open University provide funding as founding partners of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

A pre-pandemic study on PhD students’ mental health showed that they often struggle with such issues. Financial insecurity and feelings of isolation can be among the factors affecting students’ wellbeing.

The pandemic made the situation worse. We carried out research that looked into the impact of the pandemic on PhD students, surveying 1,780 students in summer 2020. We asked them about their mental health, the methods they used to cope and their satisfaction with their progress in their doctoral study.

Unsurprisingly, the lockdown in summer 2020 affected the ability to study for many. We found that 86% of the UK PhD students we surveyed reported a negative impact on their research progress.

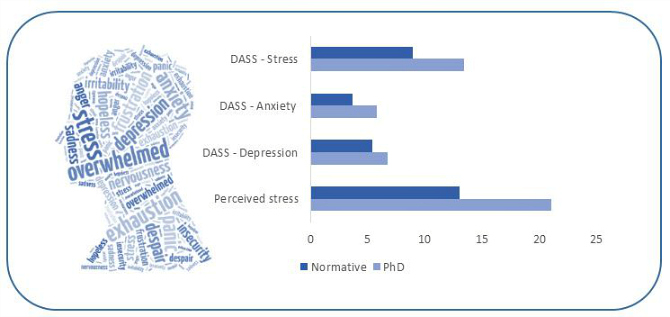

But, alarmingly, 75% reported experiencing moderate to severe depression. This is a rate significantly higher than that observed in the general population and pre-pandemic PhD student cohorts .

Risk of depression

Our findings suggested an increased risk of depression among those in the research-heavy stage of their PhD – for example during data collection or laboratory experiments. This was in contrast to those in the initial stages, or who were nearing the end of their PhD and writing up their research. The data collection stage was more likely to have been disrupted by the pandemic.

Our research also showed that PhD students with caring responsibilities faced a greatly increased risk of depression. In our our study , we found that PhD students with childcare responsibilities were 14 times more likely to develop depressive symptoms than PhD students without children.

This does align with findings on people in the general UK population with childcare responsibilities during the pandemic. Adults with childcare responsibilities were 1.4 times more likely to develop depression or anxiety compared to their counterparts without children or childcare duties.

It was also interesting to find that PhD students facing the disruption caused by the pandemic who did not receive an extension – extra financial support and time beyond the expected funding period – or were uncertain about whether they would receive an extension at the time of our study, were 5.4 times more likely to experience significant depression.

Our research also used a questionnaire designed to measure effective and ineffective ways to cope with stressful life events. We used this to look at which coping skills – strategies to deal with challenges and difficult situations — used by PhD students were associated with lower depression levels. These “good” strategies included “getting comfort and understanding from someone” and “taking action to try to make the situation better”.

Interestingly, female PhD students, who were slightly less likely than men to experience significant depression, showed a greater tendency to use good coping approaches compared to their counterparts. Specifically, they favoured the above two coping strategies that are associated with lower levels of depression.

On the other hand, certain coping strategies were associated with higher depression levels. Prominent among these were self-critical tendencies and the use of substances like alcohol or drugs to cope with challenging situations.

A supportive environment

Creating a supportive environment is not solely the responsibility of individual students or academic advisors. Universities and funding bodies must play a proactive role in mitigating the challenges faced by PhD students.

By taking proactive steps, universities could create a more supportive environment for their students and help to ensure their success.

Training in coping skills could be extremely beneficial for PhD students. For instance, the University of Cambridge includes this training as part of its building resilience course .

A focus on good strategies or positive reframing – focusing on positive aspects and potential opportunities – could be crucial. Additionally, encouraging PhD students to seek emotional support may also help reduce the risk of depression.

Another example is the establishment of PhD wellbeing support groups , an intervention funded by the Office for Students and Research England Catalyst Fund .

Groups like this serve as a platform for productive discussions and meaningful interactions among students, facilitated by the presence of a dedicated mental health advisor.

Our research showed how much financial insecurity and caring responsibilities had an effect on mental health. More practical examples of a supportive environment offered by universities could include funded extensions to PhD study and the availability of flexible childcare options.

By creating supportive environments, universities can invest in the success and wellbeing of the next generation of researchers.

- Higher education

- Mental health

- Coping strategies

- PhD students

- Give me perspective

University Relations Manager

2024 Vice-Chancellor's Research Fellowships

Head of Research Computing & Data Solutions

Community member RANZCO Education Committee (Volunteer)

Director of STEM

- Biochemistry and Molecular Biology

- Biostatistics

- Environmental Health and Engineering

- Epidemiology

- Health Policy and Management

- Health, Behavior and Society

- International Health

- Mental Health

- Molecular Microbiology and Immunology

- Population, Family and Reproductive Health

- Program Finder

- Admissions Services

- Course Directory

- Academic Calendar

- Hybrid Campus

- Lecture Series

- Convocation

- Strategy and Development

- Implementation and Impact

- Integrity and Oversight

- In the School

- In the Field

- In Baltimore

- Resources for Practitioners

- Articles & News Releases

- In The News

- Statements & Announcements

- At a Glance

- Student Life

- Strategic Priorities

- Inclusion, Diversity, Anti-Racism, and Equity (IDARE)

- What is Public Health?

Doctor of Philosophy (PhD)

Offered By: Department of Mental Health

Onsite | Full-Time | 4 – 5 years

- MSPH Field Placements

- Master's Essays

- MAS Application Fee Waiver Requirements

- Master of Arts and Master of Science in Public Health (MA/MSPH)

- Master of Arts in Public Health Biology (MAPHB)

- Master of Bioethics (MBE)

- Mission, Vision, and Values

- Student Experience

- Program Outcomes

- For Hopkins Undergraduate Students

- Master of Health Science (MHS) - Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology

- Master of Health Science (MHS) - Department of Epidemiology

- Alumni Update

- MHS Combined with a Certificate Program

- Master of Health Science (MHS) - Department of Molecular Microbiology and Immunology

- Bachelor's/MHS in Health Economics and Outcomes Research

- MHS HEOR Careers

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Master of Health Science (MHS)

- Concurrent School-Wide Master of Health Science Program in Biostatistics

- Master of Health Science - Department of Population, Family and Reproductive Health

- Master of Health Science Online (MHS) - Department of Population, Family and Reproductive Health

- Careers in Health Economics

- Core Competencies

- Meet the Director

- What is Health Economics

- MPH Capstone Schedule

- Concentrations

- Online/Part-Time Format

- Requirements

Tuition and Funding

- Executive Board Faculty

- Master of Science (ScM) - Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology

- Master of Science (ScM) - Department of Biostatistics

- Master of Science (ScM) - Department of Epidemiology

- Master of Science (ScM) - Department of Molecular Microbiology and Immunology

- Bachelor's/MSPH in Health Policy

- FAQ for MSPH in Health Policy

- Field Placement Experience

- MSPH Capstone

- MSPH Practicum

- Required and Elective Courses

- Student Timeline

- Career Opportunities

- 38-Week Dietetics Practicum

- Completion Requirements

- MSPH/RD Program FAQ

- Program Goals

- Application Fee Waiver Requirements

- Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) - Department of Biostatistics

- Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) - Department of Epidemiology

- Program Goals and Expectations

- Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) - Department of Molecular Microbiology and Immunology

- Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) - Department of Population, Family and Reproductive Health

- Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) in Clinical Investigation

- Recent Graduates and Dissertation Titles

- PhD Funding

- PhD TA Requirement

- Recent Dissertation Titles

- JHU-Tsinghua Doctor of Public Health

- Prerequisites

- Concentration in Women’s and Reproductive Health

- Custom Track

- Concentration in Environmental Health

- Concentration in Global Health: Policy and Evaluation

- Concentration in Health Equity and Social Justice

- Concentration in Health Policy and Management

- Concentration in Implementation Science

- Combined Bachelor's / Master's Programs

- Concurrent MHS Option for BSPH Doctoral Students

- Concurrent MSPH Option for JHSPH Doctoral students

- Doctor of Medicine and Doctor of Philosophy (MD/PhD)

- Adolescent Health Certificate Program

- Bioethics Certificate Program

- Clinical Trials Certificate Program

- Community- Based Public Health Certificate Program

- Demographic Methods Certificate Program

- Epidemiology for Public Health Professionals Certificate Program

- Evaluation: International Health Programs Certificate Program

- Frequently Asked Questions for Certificate Programs

- Gender and Health Certificate Program

- Gerontology Certificate Program

- Global Digital Health Certificate Program

- Global Health Certificate Program

- Global Health Practice Certificate Program

- Health Communication Certificate Program

- Health Disparities and Health Inequality Certificate Program

- Health Education Certificate Program

- Health Finance and Management Certificate Program

- Health and Human Rights Certificate Program

- Healthcare Epidemiology and Infection Prevention and Control Certificate Program

- Humanitarian Health Certificate Program

- Implementation Science and Research Practice Certificate Program

- Injury and Violence Prevention Certificate Program

- International Healthcare Management and Leadership Certificate Program

- Leadership for Public Health and Healthcare Certificate Program

- Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer (LGBTQ) Public Health Certificate Program

- Maternal and Child Health Certificate Program

- Mental Health Policy, Economics and Services Certificate Program

- Non-Degree Students General Admissions Info

- Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety Certificate Program

- Population Health Management Certificate Program

- Population and Health Certificate Program

- Public Health Advocacy Certificate Program

- Public Health Economics Certificate Program

- Public Health Informatics Certificate Program

- Public Health Practice Certificate Program

- Public Health Training Certificate for American Indian Health Professionals

- Public Mental Health Research Certificate Program

- Quality, Patient Safety and Outcomes Research Certificate Program

- Quantitative Methods in Public Health Certificate Program

- Requirements for Successful Completion of a Certificate Program

- Rigor, Reproducibility, and Responsibility in Scientific Practice Certificate Program

- Risk Sciences and Public Policy Certificate Program

- Spatial Analysis for Public Health Certificate Program

- Training Certificate in Public Health

- Tropical Medicine Certificate Program

- Tuition for Certificate Programs

- Vaccine Science and Policy Certificate Program

- Online Student Experience

- MAS and Affiliated Certificate Programs

- Barcelona Information

- Registration, Tuition, and Fees

- Agency Scholarship Application

- General Scholarship Application

- UPF Scholarship Application

- Course Evaluations

- Online Courses

- Registration

- General Institute Tuition Information

- International Students

- Directions to the Bloomberg School

- All Courses

- Important Guidance for ONSITE Students

- D.C. Courses

- Registration and Fees

- Cancellation and Closure Policies

- Application Procedures

- Career Search

- Current Activities

- Current Trainees

- Related Links

- Process for Appointing Postdoctoral Fellows

- Message from the Director

- Program Details

- Admissions FAQ

- Current Residents

- Elective Opportunities for Visiting Trainees

- What is Occupational and Environmental Medicine?

- Admissions Info

- Graduates by Year

- Compensation and Benefits

- How to Apply

- Academic Committee

- Course Details and Registration

- Tuition and Fees

- ONLINE SOCI PROGRAM

- Principal Faculty

- General Application

- JHHS Application

- Our Faculty

- Descripción los Cursos

- Programa en Epidemiología para Gestores de Salud, Basado en Internet

- Consultants

- Britt Dahlberg, PhD

- Joke Bradt, PhD, MT-BC

- Mark R. Luborsky, PhD

- Marsha Wittink, PhD

- Rebekka Lee, ScD

- Su Yeon Lee-Tauler, PhD

- Theresa Hoeft, PhD

- Vicki L. Plano Clark, PhD

- Program Retreat

- Mixed Methods Applications: Illustrations

- Announcements

- 2023 Call for Applications

- Jennifer I Manuel, PhD, MSW

- Joke Bradt, PhD

- Josiemer Mattei, PhD, MPH

- Justin Sanders, MD, MSc

- Linda Charmaran, PhD

- Nao Hagiwara, PhD

- Nynikka R. A. Palmer, DrPH, MPH

- Olayinka O. Shiyanbola, BPharm, PhD

- Sarah Ronis, MD, MPH

- Susan D. Brown, PhD

- Tara Lagu, MD, MPH

- Theresa Hoft, PhD

- Wynne E. Norton, PhD

- Yvonne Mensa-Wilmot, PhD, MPH

- A. Susana Ramírez, PhD, MPH

- Animesh Sabnis, MD, MSHS

- Autumn Kieber-Emmons, MD, MPH

- Benjamin Han, MD, MPH

- Brooke A. Levandowski, PhD, MPA

- Camille R. Quinn, PhD, AM, LCSW

- Justine Wu, MD, MPH

- Kelly Aschbrenner, PhD

- Kim N. Danforth, ScD, MPH

- Loreto Leiva, PhD

- Marie Brault, PhD

- Mary E. Cooley, PhD, RN, FAAN

- Meganne K. Masko, PhD, MT-BC/L

- PhuongThao D. Le, PhD, MPH

- Rebecca Lobb, ScD, MPH

- Allegra R. Gordon, ScD MPH

- Anita Misra-Hebert, MD MPH FACP

- Arden M. Morris, MD, MPH

- Caroline Silva, PhD

- Danielle Davidov, PhD

- Hans Oh, PhD

- J. Nicholas Dionne-Odom, PhD RN ACHPN

- Jacqueline Mogle, PhD

- Jammie Hopkins, DrPH, MS

- Joe Glass, PhD MSW

- Karen Whiteman, PhD MSW

- Katie Schultz, PhD MSW

- Rose Molina, MD

- Uriyoán Colón-Ramos, ScD MPA

- Andrew Riley, PhD

- Byron J. Powell, PhD, LCSW

- Carrie Nieman MD, MPH

- Charles R. Rogers, PhD, MPH, MS, CHES®

- Emily E. Haroz, PhD

- Jennifer Tsui, Ph.D., M.P.H.

- Jessica Magidson, PhD

- Katherine Sanchez, PhD, LCSW

- Kelly Doran, MD, MHS

- Kiara Alvarez, PhD

- LaPrincess C. Brewer, MD, MPH

- Melissa Radey, PhD, MA, MSSW

- Sophia L. Johnson, PharmD, MPH, PhD

- Supriya Gupta Mohile, MD, MS

- Virginia McKay, PhD

- Andrew Cohen, MD, PhD

- Angela Chen, PhD, PMHNP-BC, RN

- Christopher Salas-Wright, PhD, MSW

- Eliza Park MD, MS

- Jaime M. Hughes, PhD, MPH, MSW

- Johanne Eliacin, PhD, HSPP

- Lingrui Liu ScD MS

- Meaghan Kennedy, MD

- Nicole Stadnick, PhD, MPH

- Paula Aristizabal, MD

- Radhika Sundararajan, MD

- Sara Mamo, AuD, PhD

- Tullika Garg, MD MPH FACS

- Allison Magnuson, DO

- Ariel Williamson PhD, DBSM

- Benita Bamgbade, PharmD, PhD

- Christopher Woodrell MD

- Hung-Jui (Ray) Tan, MD, MSHPM

- Jasmine Abrams, PhD

- Jose Alejandro Rauh-Hain, MD

- Karen Flórez, DrPH, MPH

- Lavanya Vasudevan, PhD, MPH, CPH

- Maria Garcia, MD, MPH

- Robert Brady, PhD

- Saria Hassan, MD

- Scherezade Mama, DrPH

- Yuan Lu, ScD

- 2021 Scholars

- Sign Up for Our Email List

- Workforce Training

- Cells-to-Society Courses

- Course/Section Numbers Explained

- Pathway Program with Goucher College

- The George G. Graham Lecture

About the PhD in Mental Health Program

The PhD degree is a research-oriented doctoral degree. In the first two years, students take core courses in the Departments of Mental Health, Biostatistics, and Epidemiology, in research ethics, and attend weekly department seminars. Students must complete a written comprehensive exam (in January of their second year), a preliminary exam, two presentations and a final dissertation including presentation and defense. Throughout their time in the department, we encourage all doctoral students to participate in at least one research group of the major research programs in the department: Substance Use Epidemiology, Global Mental Health, Mental Health and Aging, Mental Health Services and Policy, Methods, Prevention Research, Psychiatric and Behavioral Genetic Epidemiology, Psychiatric Epidemiology, and Autism and Developmental Disabilities.

PhD in Mental Health Program Highlights

One-of-a-kind.

We are the only department of mental health at a school of public health in the U.S.

WORLD-CLASS MENTORSHIP

Get research experience and mentorship from renowned public mental health experts

Research Opportunities

Students conduct original research with practical applications

Domestic and international opportunities

Conduct research in the U.S. or abroad

What Can You Do With a Graduate Degree In Mental Health?

Visit the Graduate Employment Outcomes Dashboard to learn about Bloomberg School graduates' employment status, sector, and salaries.

Sample Careers

- Assistant Professor

- Postdoctoral Fellow

- Psychiatric Epidemiologist

- Prevention Scientist

- Social and Behavioral Scientist

Curriculum for the PhD in Mental Health

Browse an overview of the requirements for this PhD program in the JHU Academic Catalogue , explore all course offerings in the Bloomberg School Course Directory .

Current students can view the Department of Mental Health's student handbook on the Info for Current Students page .

Research Areas

The Department of Mental Health covers a wide array of topics related to mental health, mental illness and substance abuse. Faculty and students from multiple disciplines work together within and across several major research areas.

Admissions Requirements

For general admissions requirements, please visit the How to Apply page.

Standardized Test Scores

Standardized test scores are not required and not reviewed for this program. If you have taken a standardized test such as the GRE, GMAT, or MCAT and want to submit your scores, please note that they will not be used as a metric during the application review. Applications will be reviewed holistically based on all required application components.

Program Faculty Spotlight

Judith K. Bass

Judith Bass, PhD '04, MPH, MIA, is an implementation science researcher, with a broad background in sociology, economic development studies, and psychiatric epidemiology.

Renee M. Johnson

Renee M. Johnson, PhD, MPH, uses social epidemiology and behavioral science methods to investigate injury/violence, substance use, and overdose prevention.

George W. Rebok

George Rebok, PhD, MA, is a life-span developmental psychologist who develops community-based interventions to prevent age-related cognitive decline and reduce dementia risk.

Heather E. Volk

Heather Volk, PhD, MPH, seeks to identify factors that relate to the risk and progression of neurodevelopment disorders.

Per the Collective Bargaining Agreement (CBA) with the JHU PhD Union, the minimum guaranteed 2025-2026 academic year stipend is $50,000 for all PhD students with a 4% increase the following year. Tuition, fees, and medical benefits are provided, including health insurance premiums for PhD student’s children and spouses of international students, depending on visa type. The minimum stipend and tuition coverage is guaranteed for at least the first four years of a BSPH PhD program; specific amounts and the number of years supported, as well as work expectations related to that stipend will vary across departments and funding source. Please refer to the CBA to review specific benefits, compensation, and other terms. Need-Based Relocation Grants Students who are admitted to PhD programs at JHU starting in Fall 2023 or beyond can apply to receive a need-based grant to offset the costs of relocating to be able to attend JHU. These grants provide funding to a portion of incoming students who, without this money, may otherwise not be able to afford to relocate to JHU for their PhD program. This is not a merit-based grant. Applications will be evaluated solely based on financial need. View more information about the need-based relocation grants for PhD students .

Questions about the program? We're happy to help.

Prospective Student or Applicant Inquiries [email protected]

Compare Programs

- Check out similar programs at the Bloomberg School to find the best fit.

- Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) in International Health

- Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) in Epidemiology

- Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) in Health Policy and Management

- Open access

- Published: 26 August 2020

Understanding the mental health of doctoral researchers: a mixed methods systematic review with meta-analysis and meta-synthesis

- Cassie M. Hazell ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5868-9902 1 ,

- Laura Chapman 2 ,

- Sophie F. Valeix 3 ,

- Paul Roberts 4 ,

- Jeremy E. Niven 5 &

- Clio Berry 6

Systematic Reviews volume 9 , Article number: 197 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

15k Accesses

66 Citations

78 Altmetric

Metrics details

Data from studies with undergraduate and postgraduate taught students suggest that they are at an increased risk of having mental health problems, compared to the general population. By contrast, the literature on doctoral researchers (DRs) is far more disparate and unclear. There is a need to bring together current findings and identify what questions still need to be answered.

We conducted a mixed methods systematic review to summarise the research on doctoral researchers’ (DRs) mental health. Our search revealed 52 articles that were included in this review.

The results of our meta-analysis found that DRs reported significantly higher stress levels compared with population norm data. Using meta-analyses and meta-synthesis techniques, we found the risk factors with the strongest evidence base were isolation and identifying as female. Social support, viewing the PhD as a process, a positive student-supervisor relationship and engaging in self-care were the most well-established protective factors.

Conclusions

We have identified a critical need for researchers to better coordinate data collection to aid future reviews and allow for clinically meaningful conclusions to be drawn.

Systematic review registration

PROSPERO registration CRD42018092867

Peer Review reports

Student mental health has become a regular feature across media outlets in the United Kingdom (UK), with frequent warnings in the media that the sector is facing a ‘mental health crisis’ [ 1 ]. These claims are largely based on the work of regulatory authorities and ‘grey’ literature. Such sources corroborate an increase in the prevalence of mental health difficulties amongst students. In 2013, 1 in 5 students reported having a mental health problem [ 2 ]. Only 3 years later, however, this figure increased to 1 in 4 [ 3 ]. In real terms, this equates to 21,435 students disclosing mental health problems in 2013 rising to 49,265 in 2017 [ 4 ]. Data from the Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA) demonstrates a 210% increase in the number of students terminating their studies reportedly due to poor mental health [ 5 ], while the number of students dying by suicide has consistently increased in the past decade [ 6 ].

This issue is not isolated to the UK. In the United States (US), the prevalence of student mental health problems and use of counselling services has steadily risen over the past 6 years [ 7 ]. A large international survey of more than 14,000 students across 8 countries (Australia, Belgium, Germany, Mexico, Northern Ireland, South Africa, Spain and the United States) found that 35% of students met the diagnostic criteria for at least one common mental health condition, with highest rates found in Australia and Germany [ 8 ].

The above figures all pertain to undergraduate students. Finding equivalent information for postgraduate students is more difficult, and where available tends to combine data for postgraduate taught students and doctoral researchers (DRs; also known as PhD students or postgraduate researchers) (e.g. [ 4 ]). The latest trend analysis based on data from 36 countries suggests that approximately 2.3% of people will enrol in a PhD programme during their lifetime [ 9 ]. The countries with the highest number of DRs are the US, Germany and the UK [ 10 ]. At present, there are more than 281,360 DRs currently registered across these three countries alone [ 11 , 12 ], making them a significant part of the university population. The aim of this systematic review is to bring attention specifically to the mental health of DRs by summarising the available evidence on this issue.

Using a mixed methods approach, including meta-analysis and meta-synthesis, this review seeks to answer three research questions: (1) What is the prevalence of mental health difficulties amongst DRs? (2) What are the risk factors associated with poor mental health in DRs? And (3) what are the protective factors associated with good mental health in DRs?

Literature search

We conducted a search of the titles and abstracts of all article types within the following databases: AMED, BNI, CINAHL, Embase, HBE, HMIC, Medline, PsycInfo, PubMed, Scopus and Web of Science. The same search terms were used within all of the databases, and the search was completed on the 13th April 2018. Our search terms were selected to capture the variable terms used to describe DRs, as well as the terms used to describe mental health, mental health problems and related constructs. We also reviewed the reference lists of all the papers included in this review. Full details of the search strategy are provided in the supplementary material .

Inclusion criteria

Articles meeting the following criteria were considered eligible for inclusion: (1) the full text was available in English; (2) the article presented empirical data; (3) all study participants, or a clearly delineated sub-set, were studying at the doctoral level for a research degree (DRs or equivalent); and (4) the data collected related to mental health constructs. The last of these criteria was operationalised (a) for quantitative studies as having at least one mental health-related outcome measure, and (b) for qualitative studies as having a discussion guide that included questions related to mental health. We included university-published theses and dissertations as these are subjected to a minimum level of peer-review by examiners.

Exclusion criteria

In order to reduce heterogeneity and focus the review on doctoral research as opposed to practice-based training, we excluded articles where participants were studying at the doctoral level, but their training did not focus on research (e.g. PsyD doctorate in Clinical Psychology).

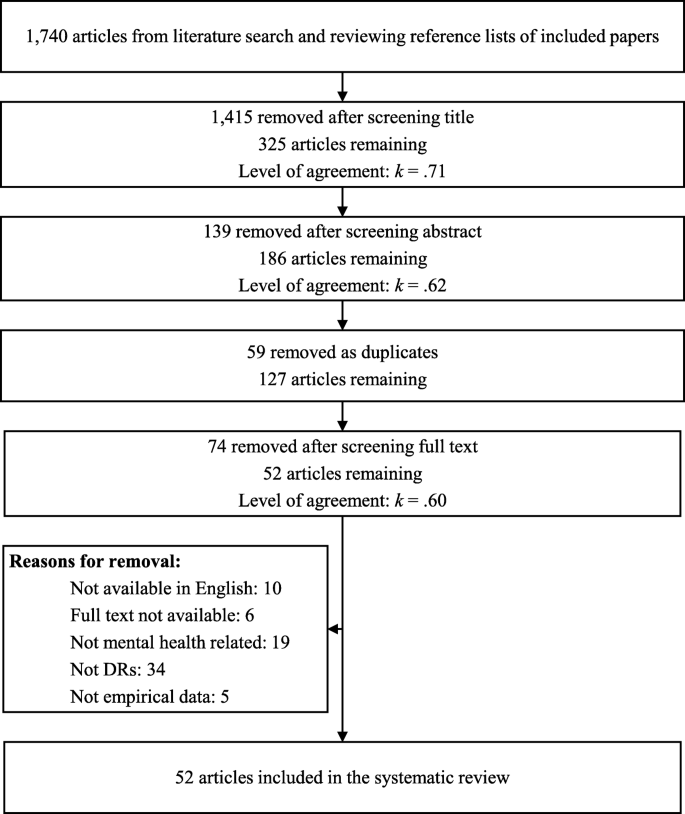

Screening articles

Papers were screened by one of the present authors at the level of title, then abstract, and finally at full text (Fig. 1 ). Duplicates were removed after screening at abstract. At each level of screening, a random 20% sub-set of articles were double screened by another author, and levels of agreement were calculated (Cohen’s kappa [ 13 ]). Where disagreements occurred between authors, a third author was consulted to decide whether the paper should or should not be included. All kappa values evidence at least moderate agreement between authors [ 14 ]—see Fig. 1 for exact kappa values.

PRISMA diagram of literature review process

Data extraction

This review reports on both quantitative and qualitative findings, and separate extraction methods were used for each. Data extraction was performed by authors CH, CB, SV and LC.

Quantitative data extraction

The articles in this review used varying methods and measures. To accommodate this heterogeneity, multiple approaches were used to extract quantitative data. Where available, we extracted (a) descriptive statistics, (b) correlations and (c) a list of key findings. For all mental health outcome measures, we extracted the means and standard deviations for the DR participants, and where available for the control group (descriptive statistics). For studies utilising a within-subjects study design, we extracted data where a mental health outcome measure was correlated with another construct (correlations). Finally, to ensure that we did not lose important findings that did not use descriptive statistics or correlations, we extracted the key findings from the results sections of each paper (list of key findings). Key findings were identified as any type of statistical analysis that included at least one mental health outcome.

Qualitative data extraction

In line with the meta-ethnographic method [ 15 ] and our interest in the empirical data as well as the authors’ interpretations thereof, i.e. the findings of each article [ 16 ], the data extracted from the articles comprised both results/findings and discussion/conclusion sections. For articles reporting qualitative findings, we extracted the results and discussion sections from articles verbatim. Where articles used mixed methods, only the qualitative section of the results was extracted. Methodological and setting details from each article were also extracted and provided (see Appendix A) in order to contextualise the studies.

Data analysis

Quantitative data analysis, descriptive statistics.

We present frequencies and percentages of the constructs measured, the tools used and whether basic descriptive statistics ( M and SD ) were reported. The full data file is available from the first author upon request.

Effect sizes

Where studies had a control group, we calculated a between-group effect size (Cohen’s d ) using the formula reported by Wilson [ 17 ], and interpreted using the standard criteria [ 13 ]. For all other studies, we sought to compare results with normative data where the following criteria were satisfied: (a) at least three studies reported data using the same mental health assessment tool; (b) empirical normative data were available; and (c) the scale mean/total had been calculated following original authors’ instructions. Only the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) 10- [ 18 ] and 14-item versions [ 19 ] met these criteria. Normative data were available from a sample of adults living in the United States: collected in 2009 for the 10-item version ( n = 2000; M = 15.21; SD = 7.28) [ 20 ] and in 1983 for the 14-item version ( n = 2355; M = 19.62; SD = 7.49) [ 18 ].

The meta-analysis of PSS data was conducted using MedCalc [ 21 ], and based on a random effects model, as recommended by [ 22 ]. The between-group effect sizes (DRs versus US norms) were calculated comparing PSS means and standard deviations in the respective groups. The effect sizes were weighted using the variable variances [ 23 ].

Correlations

Where at least three studies reported data reflecting a bivariate association between a mental health and another variable, we summarised this data into a meta-analysis using the reported r coefficients and sample sizes. Again, we used MedCalc [ 21 ] to conduct the analysis using a random effects model, based on the procedure outlined by Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins and Rothstein [ 24 ]. This analysis approach involves converting correlation coefficients into Fisher’s z values [ 25 ], calculating the summary of Fisher’s z , and then converting this to a summary correlation coefficient ( r ). The effect sizes were weighted in line with the Hedges and Ollkin [ 23 ] method. Heterogeneity was assessed using the Q statistic, and I 2 value—both were interpreted according to the GRADE criteria [ 26 ]. Where correlations could not be summarised within a meta-analysis, we have reported these descriptively.

Due to the heterogenous nature of the studies, the above methods could not capture all of the quantitative data. Therefore, additional data (e.g. frequencies, statistical tests) reported in the identified articles was collated into a single document, coded as relating to prevalence, risk or protective factors and reported as a narrative review.

Qualitative data analysis

We used thematic analytic methods to analyse the qualitative data. We followed the thematic synthesis method [ 16 , 27 ] and were informed by a thematic analysis approach [ 28 , 29 ]. We took a critical realist epistemological stance [ 30 , 31 ] and aimed to bring together an analysis reflecting meaningful patterns amongst the data [ 29 ] or demi-regularities, and identifying potential social mechanisms that might influence the experience of such phenomena [ 31 ]. The focus of the meta-synthesis is interpretative rather than aggregative [ 32 ].

Coding was line by line, open and complete. Following line-by-line coding of all articles, a thematic map was created. Codes were entered on an article-by-article basis and then grouped and re-grouped into meaningful patterns. Comparisons were made across studies to attempt to identify demi-regularities or patterns and contradictions or points of departure. The thematic map was reviewed in consultation with other authors to inductively create and refine themes. Thematic summaries were created and brought together into a first draft of the thematic structure. At this point, each theme was compared against the line-by-line codes and the original articles in order to check its fit and to populate the written account with illustrative quotations.

Research rigour

The qualitative analysis was informed by independent coding by authors CB and SV, and analytic discussions with CH, SV and LC. Our objective was not to capture or achieve inter-rater reliability, rather the analysis was strengthened through involvement of authors from diverse backgrounds including past and recent PhD completion, experiences of mental health problems during PhD completion, PhD supervision experience, experience as employees in a UK university doctoral school and different nationalities. In order to enhance reflexivity, CB used a journal throughout the analytic process to help notice and bracket personal reflections on the data and the ways in which these personal reflections might impact on the interpretation [ 29 , 33 ]. The ENTREQ checklist [ 34 ] was consulted in the preparation of this report to improve the quality of reporting.

Quality assessment

Quantitative data.

The quality of the quantitative papers was assessed using the STROBE combined checklist [ 35 ]. A random 20% sub-sample of these studies were double-coded and inter-rater agreement was 0.70, indicating ‘substantial’ agreement [ 14 ]. The maximum possible quality score was 23, with a higher score indicating greater quality, with the mean average of 15.97, and a range from 0 to 22. The most frequently low-scoring criteria were incomplete reporting regarding the management of missing data, and lack of reported efforts to address potential causes of bias.

Qualitative data

There appeared to be no discernible pattern in the perceived quality of studies; the highest [ 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 ] and lowest scoring [ 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 ] studies reflected both theses and journal publications, a variety of locations and settings and different methodologies. The most frequent low-scoring criteria were relating to the authors’ positions and reflections thereof (i.e. ‘Qualitative approach and research paradigm’, ‘Researcher characteristics and reflexivity’, ‘Techniques to enhance trustworthiness’, ‘Limitations’, ‘Conflict of interest and Funding’). Discussions of ethical issues and approval processes was also frequently absent. We identified that we foregrounded higher quality studies in our synthesis in that these studies appeared to have greater contributions reflected in the shape and content of the themes developed and were more likely to be the sources of the selected illustrative quotes.

Mixed methods approach

The goal of this review is to answer the review questions by synthesising the findings from both quantitative and/or qualitative studies. To achieve our goal, we adopted an integrated approach [ 47 ], whereby we used both quantitative and qualitative methods to answer the same review question, and draw a synthesised conclusion. Different analysis approaches were used for the quantitative and qualitative data and are therefore initially reported separately within the methods. A separate synthesised summary of the findings is then provided.

Overview of literature

Of the 52 papers included in this review (Table 1 ), 7 were qualitative, 29 were quantitative and 16 mixed methods. Most articles (35) were peer-reviewed papers, and the minority were theses (17). Only four of the articles included a control group; in three instances comprising students (but not DRs) and in the other drawn from the general population.

Quantitative results

Thirty-five papers reported quantitative data, providing 52 reported sets of mental health related data (an average of 1.49 measures per study): 24 (68.57%) measured stress, 10 (28.57%) anxiety, 9 (25.71%) general wellbeing, 5 (14.29%) social support, 3 (8.57%) depression and 1 (2.86%) self-esteem. Five studies (9.62%) used an unvalidated scale created for the purposes of the study. Fifteen studies (28.85%) did not report descriptive statistics.

Of the four studies that included a control group, only two of these reported descriptive statistics for both groups on a mental health outcome [ 66 , 69 ]. There is a small (Cohen’s d = 0.27) and large between-group effect (Cohen’s d = 1.15) when DRs were compared to undergraduate and postgraduate clinical psychology students respectively in terms of self-reported stress.

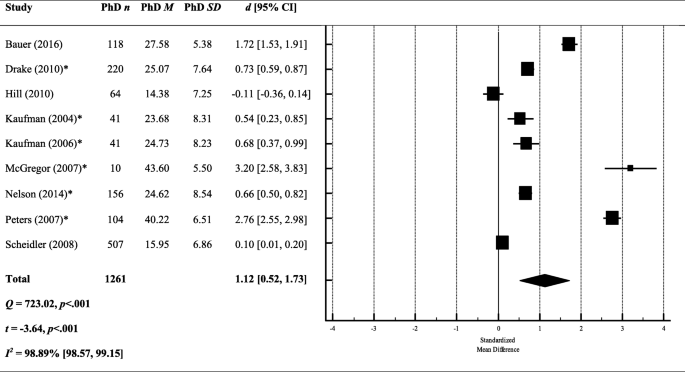

The meta-analysis of DR scores on the PSS (both 10- and 14-item versions) compared to population normative data produced a large and significant between-group effect size ( d = 1.12, 95% CI [0.52, 1.73]) in favour of DRs scoring higher on the PSS than the general population (Fig. 2 ), suggesting DRs experience significantly elevated stress. However, these findings should be interpreted in light of the significant between-study heterogeneity that can be classified as ‘considerable’ [ 26 ].

A meta-analysis of between-group effect sizes (Cohen’s d ) comparing PSS scores (both 10- and 14-item versions) from DRs and normative population data. *Studies using the 14 item version of the PSS; a positive effect size indicates DRs had a higher score on the PSS; a negative effect size indicates that the normative data produced a higher score on the PSS; black diamond = total effect size (based on random effects model); d = Cohen’s d ; Q = heterogeneity; Z = z score; I 2 = proportion of variance due to between-study heterogeneity; p = exact p value

To explore this heterogeneity, we re-ran the meta-analysis separately for the 10- and 14-item versions. The effect size remained large and significant when looking only at the studies using the 14-item version ( k = 6; d = 1.41, 95% CI [0.63, 2.19]), but was reduced and no longer significant when looking at the 10-item version only ( k = 3; d = 0.57, 95% CI [− 0.51, 1.64]). However, both effect sizes were still marred by significant heterogeneity between studies (10-item: Q = 232.02, p < .001; 14-item: Q = 356.76, p < .001).

Studies reported sufficient correlations for two separate meta-analyses; the first assessing the relationship between stress (PSS [ 18 , 19 ]) and perceived support, and the second between stress (PSS) and academic performance.

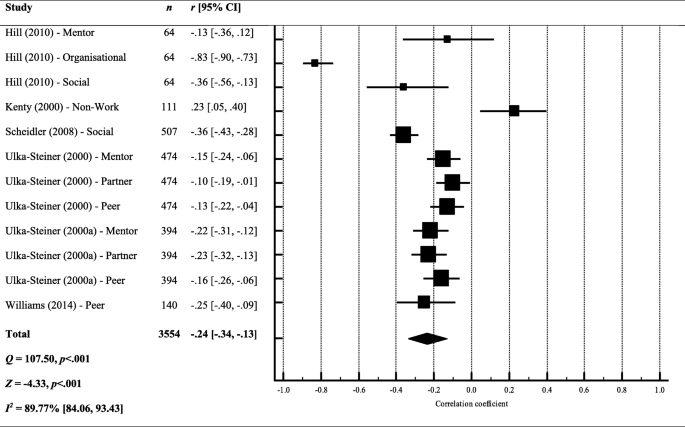

Stress x support

We included all measures related to support irrespective of whom that support came from (e.g. partner support, peer support, mentor support). The overall effect size suggests a small and significant negative correlation between stress and support ( r = − .24, 95% CI [− 0.34, − 0.13]) (see Fig. 3 ), meaning that low support is associated with greater perceived stress. However, the results should be interpreted in light of the significant heterogeneity between studies. The I 2 value quantifies this heterogeneity as almost 90% of the variance being explained by between-study heterogeneity, which is classified as ‘substantial’ (26).

Forest plot and meta-analysis of correlation coefficients testing the relationship between stress and perceived support. Black diamond = total effect size (based on random effects model); r = Pearson’s r ; Q = heterogeneity; Z = z score; I 2 = proportion of variance due to between-study heterogeneity; p = exact p value

Stress x performance

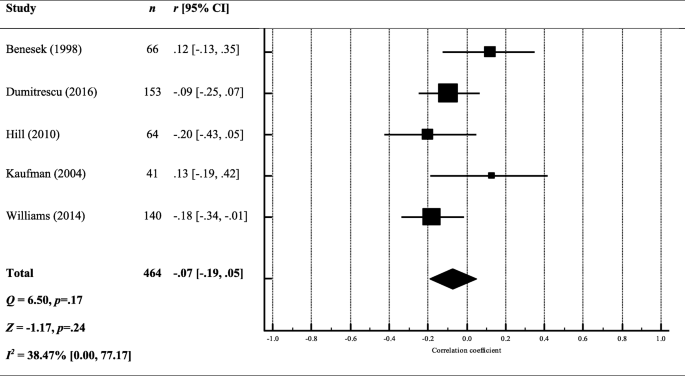

The overall effect size suggests that there is no relationship between stress and performance in their studies ( r = − .07, 95% CI [− 0.19, 0.05]) (see Fig. 4 ), meaning that DRs perception of their progress was not associated with their perceived stress This finding suggests that the amount of progress that DRs were making during their studies was not associated with stress levels.

Forest plot and meta-analysis of correlation coefficients testing the relationship between stress and performance. Black diamond = total effect size (based on random effects model); r = Pearson’s r ; Q = heterogeneity; Z = z score; I 2 = proportion of variance due to between-study heterogeneity; p = exact p value

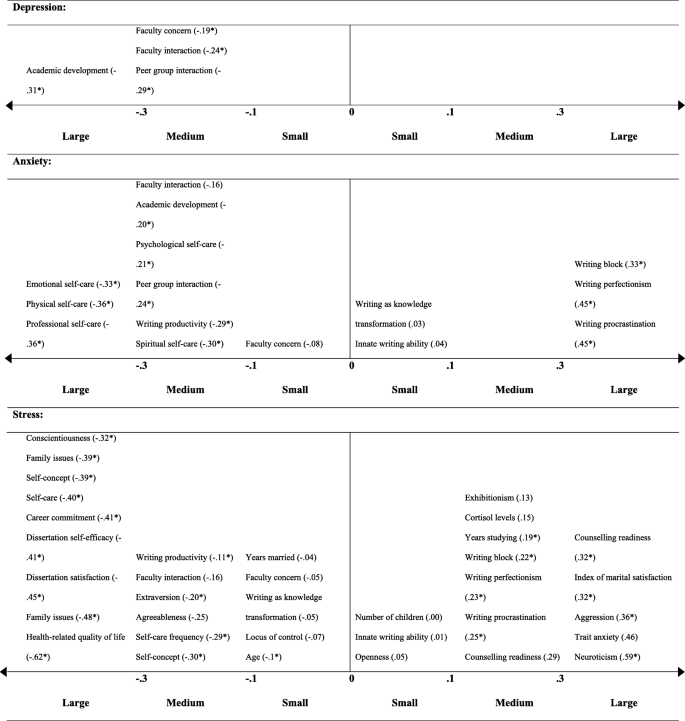

Other correlations

Correlations reported in less than three studies are summarised in Fig. 5 . Again, stress was the most commonly tested mental health variable. Self-care and positive feelings towards the thesis were consistently found to negatively correlate with mental health constructs. Negative writing habits (e.g. perfectionism, blocks and procrastination) were consistently found to positively correlate with mental health constructs. The strongest correlations were found between stress, and health related quality of life ( r = − .62) or neuroticism ( r = .59), meaning that lower stress was associated with greater quality of life and reduced neuroticism. The weakest relationships ( r < .10) were found between mental health outcomes and: faculty concern, writing as knowledge transformation, innate writing ability (stress and anxiety), years married, locus of control, number of children and openness (stress only).

Correlation coefficients testing the relationship between a mental health outcome and other construct. Correlation coefficients are given in brackets ( r ); * p < .05; each correlation coefficient reflects the results from a single study

Several studies reported DR mental health problem prevalence and this ranged from 36.30% [ 54 ] to 55.9% [ 67 ]. Using clinical cut-offs, 32% were experiencing a common psychiatric disorder [ 64 ]; with another study finding that 53.7% met the questionnaire cut-off criteria for depression, and 41.9% for anxiety [ 67 ]. One study compared prevalence amongst DRs and the general population, employees and other higher education students; in all instances, DRs had higher levels of psychological distress (non-clinical), and met criteria for a clinical psychiatric disorder more frequently [ 64 ].

Risk factors

Demographics Two studies reported no significant difference between males and females in terms of reported stress [ 57 , 73 ], but the majority suggested female DRs report greater clinical [ 80 ], and non-clinical problems with their mental health [ 37 , 64 , 79 , 83 , 89 ].

Several studies explored how mental health difficulties differed in relation to demographic variables other than gender, suggesting that being single or not having children was associated with poorer mental health [ 64 ] as was a lower socioeconomic status [ 71 ]. One study found that mental health difficulties did not differ depending on DRs’ ethnicity [ 51 ], but another found that Black students attending ‘historically Black universities’ were significantly more anxious [ 87 ]. The majority of the studies were conducted in the US, but only one study tested for cross-cultural differences: reporting that DRs in France were more psychologically distressed than those studying in the UK [ 67 ].

Work-life balance Year of study did not appear to be associated with greater subjective stress in a study involving clinical psychology DRs (Platt and Schaefer [ 75 ]), although other studies suggested greater stress reported by those in the latter part of their studies [ 89 ], who viewed their studies as a burden [ 81 ], or had external contracts, i.e. not employed by their university [ 85 ]. Regression analyses revealed that a common predictor of poor mental health was uncertainty in DR studies; whether in relation to uncertain funding [ 64 ] or uncertain progress [ 80 ]. More than two-thirds of DRs reported general academic pressure as a cause of stress, and a lack of time as preventing them from looking after themselves [ 58 ]. Being isolated was also a strong predictor of stress [ 84 ].

Protective factors

DRs who more strongly endorsed all of the five-factor personality traits (openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness and neuroticism) [ 66 ], self-reported higher academic achievement [ 40 ] and viewed their studies as a learning process (rather than a means to an end) [ 82 ] reported fewer mental health problems. DRs were able to mitigate poor mental health by engaging in self-care [ 72 ], having a supervisor with an inspirational leadership style [ 64 ] and building coping strategies [ 56 ]. The most frequently reported coping strategy was seeking support from other people [ 37 , 58 ].

Qualitative results

Meta-synthesis.

Four higher-order themes were identified: (1) Always alone in the struggle, (2) Death of personhood, (3) The system is sick and (4) Seeing, being and becoming. The first two themes reflect individual risk/vulnerability factors and the processes implicated in the experience of mental distress, the third represents systemic risk and vulnerability factors and the final theme reflects individual and systemic protective mechanisms and transformative influences. See Table 2 for details of the full thematic structure with illustrative quotes.

Always alone in the struggle

‘Always alone in the struggle’ reflects the isolated nature of the PhD experience. Two subthemes reflect different aspects of being alone; ‘Invisible, isolated and abandoned’ represents DRs’ sense of physical and psychological separation from others and ‘It’s not you, it’s me’ represents DRs’ sense of being solely responsible for their PhD process and experience.

Invisible, isolated and abandoned

Feeling invisible and isolated both within and outside of the academic environment appears a core DR experience [ 39 , 43 , 81 ]. Isolation from academic peers seemed especially salient for DRs with less of a physical presence on campus, e.g. part-time and distance students, those engaging in extensive fieldwork, outside employment and those with no peer research or lab group [ 36 , 52 , 68 ]. Where DRs reported relationships with DR peers, these were characterised as low quality or ‘not proper friendships’ and this appeared linked to a sense of essential and obvious competition amongst DRs with respect to current and future resources, support and opportunities [ 39 ], in which a minority of individuals were seen to receive the majority share [ 36 , 74 ]. Intimate sharing with peers thus appeared to feel unsafe. This reflected the competitive environment but also a sense of peer relationships being predicated on too shared an experience [ 39 ].

In addition to poor peer relations, a mismatch between the expected and observed depth of supervisor interest, engagement and was evident [ 40 , 81 ]. This mismatch was clearly associated with disappointment and anger, and a sense of abandonment, which appeared to impact negatively on DR mental health and wellbeing [ 42 ] (p. 182). Moreover, DRs perceived academic departments as complicit in their isolation; failing to offer adequate opportunities for academic and social belonging and connections [ 42 , 81 ] and including PGRs only in a fleeting or ‘hollow’ sense [ 37 ]. DRs identified this isolation as sending a broader message about academia as a solitary and unsupported pursuit; a message that could lead some DRs to self-select out of planning for future in academia [ 37 , 42 ]. DRs appeared to make sense of their lack of belonging in their department as related to their sense of being different, and that this difference might suggest they did not ‘fit in’ with academia more broadly [ 74 ]. In the short-term, DRs might expend more effort to try and achieve a social and/or professional connection and equitable access to support, opportunities and resources [ 74 ]. However, over the longer-term, the continuing perception of being professionally ‘other’ also seemed to undermine DRs’ sense of meaning and purpose [ 81 ] and could lead to opting out of an academic career [ 62 , 74 ].

Isolation within the PhD was compounded by isolation from one’s personal relationships. This personal isolation was first physical, in which the laborious nature of the PhD acted as a catalyst for the breakdown of pre-existing relationships [ 76 ]. Moreover, DRs also experienced a sense of psychological detachment [ 45 , 74 ]. Thus, the experience of isolation appeared to be extremely pervasive, with DRs feeling excluded and isolated physically and psychologically and across both their professional and personal lives.

It’s not you, it’s me

‘It’s not you, it’s me’ reflects DRs’ perfectionism as a central challenge of their PhD experience and a contributor to their sense of psychological isolation from other people. DRs’ perfectionism manifested in four key ways; firstly, in the overwhelming sense of responsibility experienced by DRs; secondly, in the tendency to position themselves as inadequate and inferior; thirdly, in cycles of perfectionist paralysis; and finally, in the tendency to find evidence which confirms their assumed inferiority.

DRs positioned themselves as solely responsible for their PhD and for the creation of a positive relationship with their supervisor [ 36 , 52 , 81 ]. DRs expressed a perceived need to capture their supervisors’ interest and attention [ 36 , 52 , 74 ], feeling that they needed to identify and sell to their supervisors some shared characteristic or interest in order to scaffold a meaningful relationship. DRs appeared to feel it necessary to assume sole responsibility for their personal lives and to prohibit any intrusion of the personal in to the professional, even in incredibly distressing circumstances [ 42 ].

DRs appeared to compare themselves against an ideal or archetypal DR and this comparison was typically unfavourable [ 37 ], with DRs contrasting the expected ideal self with their actual imperfect and fallible self [ 37 , 42 , 52 ]. DRs’ sense of inadequacy appeared acutely and frequently reflected back to them by supervisors in the form of negative or seemingly disdainful feedback and interactions [ 41 , 76 ]. DRs framed negative supervisor responses as a cue to work harder, meaning they were continually striving, but never reaching, the DR ideal [ 76 ]. This ideal-actual self-discrepancy was associated with a tendency towards punitive self-talk with clear negative valence [ 38 ].

DRs appear to commonly use self-castigation as a necessary (albeit insufficient) means to motivate themselves to improve their performance in line with perfectionistic standards [ 38 , 41 ]. The oscillation between expectation and actuality ultimately resulted in increased stress and anxiety and reduced enjoyment and motivation. Low motivation and enjoyment appeared to cause procrastination and avoidance, which lead to a greater discrepancy between the ideal and actual self; in turn, this caused more stress and anxiety and further reduced enjoyment and motivation leading to a sense of stuckness [ 76 ].

The internalisation of perceived failure was such that DRs appeared to make sense of their place, progress and possible futures through a lens of inferiority, for example, positioning themselves as less talented and successful compared to their peers [ 37 ]. Thus, instances such as not being offered a job, not receiving funding, not feeling connected to supervisors, feeling excluded by academics and peers were all made sense of in relation to DRs’ perceived relative inadequacy [ 36 ].

Death of personhood

The higher-order theme ‘Death of personhood’ reflects DRs’ identity conflict during the PhD process; a sense that DRs’ engage in a ‘Sacrifice of personal identity’ in which they feel they must give up their pre-existing self-identity, begin to conceive of themselves as purely ‘takers’ personally and professionally, thus experiencing the ‘Self as parasitic’, and ultimately experience a ‘Death of self-agency’ in relation to the thesis, the supervisor and other life roles and activities.

A sacrifice of personal identity

The sacrifice of personal identity first manifests as an enmeshment with the PhD and consequent diminishment of other roles, relationships and activities that once were integral to the DRs’ sense of self [ 59 , 76 ]. DRs tended to prioritise PhD activities to the extent that they engaged in behaviours that were potentially damaging to their personal relationships [ 76 ]. DRs reported a sense of never being truly free; almost physically burdened by the weight of their PhD and carrying with them a constant ambient guilt [ 37 , 38 , 44 , 76 ]. Time spent on non-PhD activities was positioned as selfish or indulgent, even very basic activities of living [ 76 ].

The seeming incompatibility of aspects of prior personal identity and the PhD appears to result in a sense of internal conflict or identity ‘collision’ [ 59 ]. Friends and relatives often provided an uncomfortable reflection of the DR’s changing identity, leaving DRs feeling hyper-visible and carrying the burden of intellect or trailblazer status [ 74 ]; providing further evidence for the incompatibility of their personal and current and future professional identities. Some DRs more purposefully pruned their relationships and social activities; to avoid identity dissonance, to conserve precious time and energy for their PhD work, or as an acceptance of total enmeshment with academic work as necessary (although not necessarily sufficient) for successful continuation in academia [ 40 , 52 , 77 ]. Nevertheless, the diminishment of the personal identity did not appear balanced by the development of a positive professional identity. The professional DR identity was perceived as unclear and confusing, and the adoption of an academic identity appeared to require DRs to have a greater degree of self-assurance or self-belief than was often the case [ 37 , 81 ].

Self as parasitic

Another change in identity manifested as DRs beginning to conceive of themselves as parasitic. DRs spoke of becoming ‘takers’, feeling that they were unable to provide or give anything to anyone. For some DRs, being ‘parasitic’ reflected them being on the bottom rung of the professional ladder or the ‘bottom of the pile’; thus, professionally only able to receive support and assistance rather than to provide for others. Other DRs reported more purposefully withdrawing from activities in which they were a ‘giver’, for example voluntary work, as providing or caring for others required time or energy that they no longer had [ 38 , 44 ]. Furthermore, DRs appeared to conceive of themselves as also causing difficulty or harm to others [ 81 ], as problems in relation to their PhD could lead them to unwillingly punishing close others, for example, through reducing the duration or quality of time spent together [ 38 ].

Feeling that close others were offering support appeared to heighten the awareness of the toll of the PhD on the individual and their close relationships, emphasising the huge undertaking and the often seemingly slow progress, and actually contributing to the sense of ambient guilt, shame, anger and failure [ 38 ]. Moreover, DRs spoke of feeling extreme guilt in perceiving that they had possibly sacrificed their own, and possibly family members’, current wellbeing and future financial security [ 49 ].

Death of self-agency

In addition to their sense of having to sacrifice their personal identity, DRs also expressed a loss of their sense of themselves as agentic beings. DRs expressed feeling powerless in various domains of their lives. First, DRs positioned the thesis as a powerful force able to overwhelm or swallow them [ 46 , 52 , 59 ]. Secondly, DRs expressed a sense of futility in trying to retain any sense of personal power in the climate of academia. An acute feeling of powerlessness especially in relation to supervisors was evident, with many examples provided of being treated as means to an end, as opposed to ends in themselves [ 39 , 42 , 62 ]. Supervisors did not interact with DRs in a holistic way that recognised their personhood and instead were perceived as prioritising their own will, or the will of other academics, above that of the DR [ 39 , 62 ].

Furthermore, DRs reported feeling as if they were used as a means for research production or furthering their supervisors’ reputations or careers [ 62 ]. DRs perceived that holding on to a sense of personal agency sometimes felt incompatible with having a positive supervisor relationship [ 42 ]. Thus whilst emotional distress, anger, disappointment, sadness, jealousy and resentment were clearly evident in relation to feeling excluded, used or over-powered by supervisors [ 37 , 42 , 52 , 62 ], DRs usually felt unable to change supervisor irrespective of how seriously this relationship had degraded [ 37 , 62 ]. Instead, DRs appeared to take on a position of resignation or defensive pessimism, in which they perceived their supervisors as thwarting their personhood, personal goals and preferences, but typically felt compelled to accept this as the status quo and focus on finishing their PhDs [ 42 ]. DRs resignation was such that they internalised this culture of silence and silenced themselves; tending to share litanies of problems with supervisors whilst prefacing or ending the statements with some contradictory or undermining phrase such as ‘but that’s okay’ [ 42 , 52 ].

The apparent lack of self-agency extended outward from the PhD into DRs not feeling able to curate positive life circumstances more generally [ 76 ]. A lack of time was perhaps the key struggle across both personal and professional domains, yet DRs paradoxically reported spending a lot of time procrastinating and rarely (if ever) mentioned time management as a necessary or desired coping strategy for the problem of having too little time [ 46 ]. The lack of self-agency was not only current but also felt in reference to a bleak and uncertain future; DRs lack of surety in a future in academia and the resultant sense of futility further undermined their motivation to engage currently with PhD tasks [ 38 , 40 ].

The system is sick

The higher-order theme ‘The system is sick’ represents systemic influences on DR mental health. First, ‘Most everyone’s mad here’ reflects the perceived ubiquity mental health problems amongst DRs. ‘Emperor’s new clothes’ reflects the DR experience of engaging in a performative piece in which they attempt to live in accordance with systemic rather than personal values. Finally, ‘Beware the invisible and visible walls’ reflects concerns with being caught between ephemeral but very real institutional divides.

Most everyone’s mad here

No studies focused explicitly on experiences of DRs who had been given diagnoses of mental health problems. Some study participants self-disclosed mental health problems and emphasised their pervasive impact [ 50 ]. Further lived experiences of mental distress in the absence of explicit disclosure were also clearly identifiable. The ‘typical’ presentation of DRs with respect to mental health appeared characterised as almost unanimous [ 39 ] accounts of chronic stress, anxiety and depression, emotional distress including frustration, anger and irritability, lack of mental and physical energy, somatic problems including appetite problems, headaches, physical pain, nausea and problems with drug and alcohol abuse [ 39 , 46 , 59 , 76 ]. Health anxiety, concerns regarding perceived new and unusual bodily sensations and perceived risks of developing stress-related illnesses were also common [ 46 , 59 , 76 ]. A PhD-specific numbness and hypervigilance was also reported, in which DRs might be less responsive to personal life stressors but develop an extreme sensitivity and reactivity to PhD-relevant stimuli [ 39 ].

An interplay of trait and state factors were suggested to underlie the perceived ubiquity of mental health problems amongst DRs. Etiological factors associated with undertaking a PhD specifically included the high workload, high academic standards, competing personal and professional demands, social isolation, poor resources in the university, poor living conditions and poverty, future and career uncertainty [ 36 , 41 , 43 , 46 , 49 , 76 ]. The ‘nexus’ of these factors was such that the PhD itself acted as a crucible; a process of such intensity that developing mental health problems was perhaps inevitable [ 39 ].

The perceived inevitability of mental health problems was such that DRs described people who did not experience mental health problems during a PhD as ‘lucky’ [ 39 ]. Supervisors and the wider academic system were seen to promote an expectation of suffering, for example, with academics reportedly normalising drug and alcohol problems and encouraging unhealthy working practices [ 39 ]. Furthermore, DRs felt that academics were uncaring with respect to the mental challenge of doing a PhD [ 39 ]. Nevertheless, academics were suggested to deny any culpability or accountability for mental health problems amongst DRs [ 39 , 59 , 74 ]. The cycle of indigenousness was further maintained by a lack of mental health literacy and issues with awareness, availability and access to help-seeking and treatment options amongst DRs and academics more widely [ 39 ]. Thus, DRs appeared to feel they were being let down by a system that was almost set up to cause mental distress, but within which there was a widespread denial of the size and scope of the problem and little effort put into identifying and providing solutions [ 39 , 59 ]. DRs ultimately felt that the systemic encouragement of unhealthy lifestyles in pursuit of academic success was tantamount to abuse [ 62 ].

A performance of optimum suffering

Against a backdrop of expected mental distress, DRs expressed their PhD as a performative piece. DRs first had to show just the right amount of struggle and difficulty; feeling that if they did not exhibit enough stress, distress and ill-health, their supervisors or the wider department might not believe they were taking their PhD seriously enough [ 40 ]. At the same time, DRs felt that their ‘researcher mettle’ was constantly being tested and they must rise to this challenge. This included first guarding against presenting oneself as intellectually inferior [ 36 ]. Yet it also seemed imperative not to show vulnerability more broadly [ 74 ]. Disclosing mental or physical health problems might lead not only to changed perceptions of the DR but to material disadvantage [ 74 ]. The poor response to mental health disclosures suggested to some DRs that universities might be purposefully trying to dissuade or discourage DRs with mental health problems or learning disabilities from continuing [ 74 ]. The performative piece is thus multi-layered, in that DRs must experience extreme internal psychological struggles, exhibit some lower-level signs of stress and fatigue for peer and faculty observance, yet avoid expressing any real academic or interpersonal weakness or the disclosure of any diagnosable disability or disease.

Emperor’s new clothes

DRs described feeling beholden to the prevailing culture in which it was expected to prioritise above all else developing into a competitive, self-promoting researcher in a high-performing research-active institution [ 39 , 42 ]. Supervisors often appeared the conduit for transmission of this academic ideal [ 74 ]. DRs felt reticent to act in any way which suggested that they did not personally value the pursuit of a leading research career above all else. For example, DRs felt that valuing teaching was non-conformist and could endanger their continuing success within their current institution [ 55 ]. Many DRs thus exhibited a sense of dissonance as their personal values often did not align with the institutional values they identified [ 74 ]. Yet DRs expressed a sense of powerlessness and a feeling of being ‘caught up’ in the values of the institution even when such values were personally incongruent [ 74 ]. The psychological toll of this sense of inauthenticity seemed high [ 55 ]. Where DRs acted in ways which ostensibly suggested values other than prioritising a research career, for example becoming pregnant, they sensed disapproval [ 76 ]. DRs also felt unable to challenge other ‘institutional myths’ for example, the perceived institutional denial of the duration of and financial struggle involved in completing a PhD [ 49 ]. There was a perceived tendency of academics to locate problems within DRs as opposed to acknowledging institutional or systemic inequalities [ 49 ]. DRs expressed strongly a sense in which there is inequity in support, resources and opportunities, yet universities were perceived as ignoring such inequity or labelling such divisions as based on meritocracy [ 36 , 74 ].

Beware the invisible and visible walls

DRs described the reality of working in academia as needing to negotiate a maze of invisible and visible walls. In the former case, ‘invisible walls’ reflect ephemeral norms and rules that govern academia. DRs felt that a big part of their continuing success rested upon being able to negotiate such rules [ 39 ]. Where rules were violated and explicit or implicit conflicts occurred, DRs were seen to be vulnerable to being caught in the ‘crossfire’ [ 36 ]. DRs identified academic groups and departments as being poor in explicitly identifying, discussing and resolving conflicts [ 37 ]. The intangibility of the ‘invisible walls’ gave rise to a sense of ambient anxiety about inadvertently transgressing norms and divides, such that some DRs reported behaving in ways that surprised even themselves [ 37 ].

Gendered and racial micropolitics of academic institutions were seen to manifest as more visible walls between people, with institutions privileging those with ‘insider’ status [ 36 ]. Women and people of colour typically felt excluded or disadvantaged in a myriad of observable and unobservable ways, with individuals able to experience both insider and outsider statuses simultaneously [ 36 , 37 ], for example when a male person of colour [ 36 ]. Female DRs suggested that not only must women prove themselves to a greater extent than men to receive equal access to resources, opportunities and acclaim but also are typically under additional pressure in both their professional and personal lives [ 37 , 52 , 76 ]. Women also felt that they had to take on more additional roles and responsibilities and encountered more conflicts in their personal lives compared to men [ 52 ]. Examples of professionally successful women in DRs’ departments were described as those who had crossed the divide and adopted a more traditionally male role [ 40 ]. Thus, being female or non-White were considered visible characteristics that would disadvantage people in the competitive academic environment and could give rise to a feeling of increased stress, pressure, role conflicts, and a feeling of being unsafe.

Seeing, being and becoming

The higher-order theme of ‘Seeing, being and becoming’ reflects protective and transformative influences on DR mental health. ‘De-programming’ refers to the DRs disentangling their personal beliefs and values from systemic values and also from their own tendency towards perfectionism. ‘The power of being seen’ reflects the positive impact on DR mental health afforded by feeling visible to personal and professional others. ‘Finding hope, meaning and authenticity’ refers to processes by which DRs can find or re-locate their own self-agency, purpose and re/establish a sense of living in accordance with their values. ‘The importance of multiple goals, roles and groups’ represents the beneficial aspects of accruing and sustaining multiple aspects to one’s identity and connections with others and activities outside the PhD. Finally, ‘The PhD as a process of transcendence’ reflects how the struggles involved in completing a PhD can be transformative and self-actualising.

De-programming

DRs reported being able to protect their mental health by ‘de-programming’ and disentangling their attitudes and practices from social and systemic values and norms. This disentangling helped negate DRs’ adopting unhealthy working practices and offered some protection against experiencing inauthenticity and dissonance between personal and systemic values.

First, DRs spoke of rejecting the belief that they should sacrifice or neglect personal relationships, outside interests and their self-identity in pursuit of academic achievement. DRs could opt-out entirely by choosing a ‘user-friendly’ programme [ 44 ] which encouraged balance between personal and professional goals, or else could psychologically reject the prevailing institutional discourse [ 40 ]. Rather than halting success, de-programming from the prioritisation of academia above all else was seen to be associated not only with reduced stress but greater confidence, career commitment and motivation [ 40 , 50 ]. It was also suggested possible to ‘de-programme’ in the sense of choosing not to be preoccupied by the ‘invisible walls’ of academia and psychologically ‘opt out’ of being concerned by potential conflicts, norms and rules governing academic workplace conduct [ 36 ]. Interaction with people outside of academia was seen to scaffold de-programming, by helping DRs to stay ‘grounded’ and offering a model what ‘normal’ life looks like. People outside of academia could also help DRs to see the truth by providing unbiased opinions regarding systemic practices [ 39 ].

A further way in which de-programming manifested was in DRs challenging their perfectionist beliefs. This include re-framing the goal as not trying to be the archetype of a perfect DR, and accepting that multiple demands placed on one individual invariably requires compromise [ 40 , 76 ]. DRs spoke of the need to conceptualise the PhD as a process, rather than just a product [ 46 , 82 ]. The process orientation facilitated framing of the PhD as just one-step in the broader process of becoming an academic as opposed to providing discrete evidence of worth [ 82 ]. Within this perspective, uncertainty itself could be conceived as a privilege [ 81 ]. The PhD was then seen as an opportunity rather than a test [ 37 , 46 ]. Moreover, the process orientation facilitated viewing the PhD as a means of growing into a contributing member of the research community, as opposed to needing to prove oneself to be accepted [ 82 ]. Remembering the temporary nature of the PhD was advised [ 45 ] as was holding on to a sense that not completing the PhD was also a viable life choice [ 76 ]. DRs also expressed, implicitly or explicitly, a decision to change their conceptualisation of themselves and their progress; choosing not to perceive themselves as stuck, but planning, learning and progressing [ 38 , 39 , 81 , 82 ]. This new perspective appeared to be helpful in reducing mental distress.

The power of being seen

DRs described powerful benefits to feeling seen by other people, including a sense of belonging and mattering, increased self-confidence and a sense of positive progress [ 37 ]. Being seen by others seems to provoke the genesis of an academic identity; it brings DRs into existence as academics. Being seen within the academic institution also supports mental health and can buffer emotional exhaustion [ 37 , 52 , 55 , 81 ]. DRs expressed a need to feel that supervisors, academics and peers were interested in them as people, their values, goals, struggles and successes; yet they also needed to feel that they and their research mattered and made a difference within and outside of the institution [ 42 , 52 , 81 ]. It was clear that DRs could find in their disciplinary communities the sense of belonging that often eluded them within their immediate departments [ 42 ]. Feeling a sense of belonging to the academic community seemed to buffer disengagement and amotivation during the PhD [ 81 ]. Positive engagement with the broader community was scaffolded by a sense of trust in the supervisor [ 81 ]. DRs often felt seen and supported by postdocs, especially where supervisors appeared absent or unsupportive [ 50 ].

Spending time with peers could be beneficial when there was a sense of shared experience and walking alongside each other [ 39 ]. Friendship was seen to buffer stress and protect against mental health problems through the provision of social and emotional support and help in identifying struggles [ 39 , 43 ]. In addition to relational aspects, the provision of designated physical spaces on campus or in university buildings also seemed important to being seen [ 37 ]. Peers in the university could provide DRs with further physical embodiments of being seen, for example, gift-giving in response to their birthdays or returning from leave [ 37 , 50 ]. Outside of the academic institution, DRs described how being seen by close others could support DRs to be their authentic selves, providing an antidote to the invisible walls of academia [ 50 ]. Good quality friendships within or outside academia could be life-changing, providing a visceral sense of connection, belonging and authenticity that can scaffold positive mental health outcomes during the PhD [ 39 ]. Pets could also serve to help DRs feel seen but without needing to extend too much energy into maintaining social relationships [ 50 ].

Finally, DRs also needed to see themselves, i.e. to begin to see themselves as burgeoning academics as opposed to ‘just students’ [ 81 ]. Feeling that the supervisor and broader academic community were supportive, developing one’s own network of process collaborators and successfully obtaining grant funding seemed tangible markers that helped DRs to see themselves as academics [ 37 , 81 ]. Seeing their own work published was also helpful in providing a boost in confidence and being a joyful experience [ 42 ]. Moreover, with sufficient self-agency, DRs can not only see themselves but render themselves visible to other people [ 37 ].

Multiple goals, roles and groups

In antidote to the diminished personal identity and enmeshment with the PhD, DRs benefitted from accruing and sustaining multiple goals, roles, occupations, activities and social group memberships. Although ‘costly’ in terms of increased stress and role conflicts, sustaining multiple roles and activities appeared essential for protecting against mental health problems [ 50 , 68 ].

Leisure activities appeared to support mental health through promoting physical health, buffering stress, providing an uplift to DRs’ mood and through the provision of another identity other than as an academic [ 44 , 50 , 76 ]. Furthermore, engagement in activities helped DRs to find a sense of freedom, allowing them to carve up leisure and work time and psychologically detach from their PhD [ 68 , 76 ]. Competing roles, especially family, forced DRs to distance themselves from the PhD physically which reinforced psychological separation [ 50 , 59 ]. Engaging in self-care and enjoyable activities provided a sense of balance and normalcy [ 39 , 44 , 68 ]. This normalcy was a needed antidote to abnormal pressure [ 59 ]. Even in the absence of fiercely competing roles and priorities, DRs still appeared to benefit from treating their PhD as if it is only one aspect of life [ 59 ]. Additional roles and activities reduced enmeshment with the PhD to the extent that considering not completing the PhD was less averse [ 40 ]. This position appeared to help DRs to be less overwhelmed and less sensitive to perceived and anticipated failures.

Finding hope, meaning and authenticity