How to Write a Good English Literature Essay

By Dr Oliver Tearle (Loughborough University)

How do you write a good English Literature essay? Although to an extent this depends on the particular subject you’re writing about, and on the nature of the question your essay is attempting to answer, there are a few general guidelines for how to write a convincing essay – just as there are a few guidelines for writing well in any field.

We at Interesting Literature call them ‘guidelines’ because we hesitate to use the word ‘rules’, which seems too programmatic. And as the writing habits of successful authors demonstrate, there is no one way to become a good writer – of essays, novels, poems, or whatever it is you’re setting out to write. The French writer Colette liked to begin her writing day by picking the fleas off her cat.

Edith Sitwell, by all accounts, liked to lie in an open coffin before she began her day’s writing. Friedrich von Schiller kept rotten apples in his desk, claiming he needed the scent of their decay to help him write. (For most student essay-writers, such an aroma is probably allowed to arise in the writing-room more organically, over time.)

We will address our suggestions for successful essay-writing to the average student of English Literature, whether at university or school level. There are many ways to approach the task of essay-writing, and these are just a few pointers for how to write a better English essay – and some of these pointers may also work for other disciplines and subjects, too.

Of course, these guidelines are designed to be of interest to the non-essay-writer too – people who have an interest in the craft of writing in general. If this describes you, we hope you enjoy the list as well. Remember, though, everyone can find writing difficult: as Thomas Mann memorably put it, ‘A writer is someone for whom writing is more difficult than it is for other people.’ Nora Ephron was briefer: ‘I think the hardest thing about writing is writing.’ So, the guidelines for successful essay-writing:

1. Planning is important, but don’t spend too long perfecting a structure that might end up changing.

This may seem like odd advice to kick off with, but the truth is that different approaches work for different students and essayists. You need to find out which method works best for you.

It’s not a bad idea, regardless of whether you’re a big planner or not, to sketch out perhaps a few points on a sheet of paper before you start, but don’t be surprised if you end up moving away from it slightly – or considerably – when you start to write.

Often the most extensively planned essays are the most mechanistic and dull in execution, precisely because the writer has drawn up a plan and refused to deviate from it. What is a more valuable skill is to be able to sense when your argument may be starting to go off-topic, or your point is getting out of hand, as you write . (For help on this, see point 5 below.)

We might even say that when it comes to knowing how to write a good English Literature essay, practising is more important than planning.

2. Make room for close analysis of the text, or texts.

Whilst it’s true that some first-class or A-grade essays will be impressive without containing any close reading as such, most of the highest-scoring and most sophisticated essays tend to zoom in on the text and examine its language and imagery closely in the course of the argument. (Close reading of literary texts arises from theology and the analysis of holy scripture, but really became a ‘thing’ in literary criticism in the early twentieth century, when T. S. Eliot, F. R. Leavis, William Empson, and other influential essayists started to subject the poem or novel to close scrutiny.)

Close reading has two distinct advantages: it increases the specificity of your argument (so you can’t be so easily accused of generalising a point), and it improves your chances of pointing up something about the text which none of the other essays your marker is reading will have said. For instance, take In Memoriam (1850), which is a long Victorian poem by the poet Alfred, Lord Tennyson about his grief following the death of his close friend, Arthur Hallam, in the early 1830s.

When answering a question about the representation of religious faith in Tennyson’s poem In Memoriam (1850), how might you write a particularly brilliant essay about this theme? Anyone can make a general point about the poet’s crisis of faith; but to look closely at the language used gives you the chance to show how the poet portrays this.

For instance, consider this stanza, which conveys the poet’s doubt:

A solid and perfectly competent essay might cite this stanza in support of the claim that Tennyson is finding it increasingly difficult to have faith in God (following the untimely and senseless death of his friend, Arthur Hallam). But there are several ways of then doing something more with it. For instance, you might get close to the poem’s imagery, and show how Tennyson conveys this idea, through the image of the ‘altar-stairs’ associated with religious worship and the idea of the stairs leading ‘thro’ darkness’ towards God.

In other words, Tennyson sees faith as a matter of groping through the darkness, trusting in God without having evidence that he is there. If you like, it’s a matter of ‘blind faith’. That would be a good reading. Now, here’s how to make a good English essay on this subject even better: one might look at how the word ‘falter’ – which encapsulates Tennyson’s stumbling faith – disperses into ‘falling’ and ‘altar’ in the succeeding lines. The word ‘falter’, we might say, itself falters or falls apart.

That is doing more than just interpreting the words: it’s being a highly careful reader of the poetry and showing how attentive to the language of the poetry you can be – all the while answering the question, about how the poem portrays the idea of faith. So, read and then reread the text you’re writing about – and be sensitive to such nuances of language and style.

The best way to become attuned to such nuances is revealed in point 5. We might summarise this point as follows: when it comes to knowing how to write a persuasive English Literature essay, it’s one thing to have a broad and overarching argument, but don’t be afraid to use the microscope as well as the telescope.

3. Provide several pieces of evidence where possible.

Many essays have a point to make and make it, tacking on a single piece of evidence from the text (or from beyond the text, e.g. a critical, historical, or biographical source) in the hope that this will be enough to make the point convincing.

‘State, quote, explain’ is the Holy Trinity of the Paragraph for many. What’s wrong with it? For one thing, this approach is too formulaic and basic for many arguments. Is one quotation enough to support a point? It’s often a matter of degree, and although one piece of evidence is better than none, two or three pieces will be even more persuasive.

After all, in a court of law a single eyewitness account won’t be enough to convict the accused of the crime, and even a confession from the accused would carry more weight if it comes supported by other, objective evidence (e.g. DNA, fingerprints, and so on).

Let’s go back to the example about Tennyson’s faith in his poem In Memoriam mentioned above. Perhaps you don’t find the end of the poem convincing – when the poet claims to have rediscovered his Christian faith and to have overcome his grief at the loss of his friend.

You can find examples from the end of the poem to suggest your reading of the poet’s insincerity may have validity, but looking at sources beyond the poem – e.g. a good edition of the text, which will contain biographical and critical information – may help you to find a clinching piece of evidence to support your reading.

And, sure enough, Tennyson is reported to have said of In Memoriam : ‘It’s too hopeful, this poem, more than I am myself.’ And there we have it: much more convincing than simply positing your reading of the poem with a few ambiguous quotations from the poem itself.

Of course, this rule also works in reverse: if you want to argue, for instance, that T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land is overwhelmingly inspired by the poet’s unhappy marriage to his first wife, then using a decent biographical source makes sense – but if you didn’t show evidence for this idea from the poem itself (see point 2), all you’ve got is a vague, general link between the poet’s life and his work.

Show how the poet’s marriage is reflected in the work, e.g. through men and women’s relationships throughout the poem being shown as empty, soulless, and unhappy. In other words, when setting out to write a good English essay about any text, don’t be afraid to pile on the evidence – though be sensible, a handful of quotations or examples should be more than enough to make your point convincing.

4. Avoid tentative or speculative phrasing.

Many essays tend to suffer from the above problem of a lack of evidence, so the point fails to convince. This has a knock-on effect: often the student making the point doesn’t sound especially convinced by it either. This leaks out in the telling use of, and reliance on, certain uncertain phrases: ‘Tennyson might have’ or ‘perhaps Harper Lee wrote this to portray’ or ‘it can be argued that’.

An English university professor used to write in the margins of an essay which used this last phrase, ‘What can’t be argued?’

This is a fair criticism: anything can be argued (badly), but it depends on what evidence you can bring to bear on it (point 3) as to whether it will be a persuasive argument. (Arguing that the plays of Shakespeare were written by a Martian who came down to Earth and ingratiated himself with the world of Elizabethan theatre is a theory that can be argued, though few would take it seriously. We wish we could say ‘none’, but that’s a story for another day.)

Many essay-writers, because they’re aware that texts are often open-ended and invite multiple interpretations (as almost all great works of literature invariably do), think that writing ‘it can be argued’ acknowledges the text’s rich layering of meaning and is therefore valid.

Whilst this is certainly a fact – texts are open-ended and can be read in wildly different ways – the phrase ‘it can be argued’ is best used sparingly if at all. It should be taken as true that your interpretation is, at bottom, probably unprovable. What would it mean to ‘prove’ a reading as correct, anyway? Because you found evidence that the author intended the same thing as you’ve argued of their text? Tennyson wrote in a letter, ‘I wrote In Memoriam because…’?

But the author might have lied about it (e.g. in an attempt to dissuade people from looking too much into their private life), or they might have changed their mind (to go back to the example of The Waste Land : T. S. Eliot championed the idea of poetic impersonality in an essay of 1919, but years later he described The Waste Land as ‘only the relief of a personal and wholly insignificant grouse against life’ – hardly impersonal, then).

Texts – and their writers – can often be contradictory, or cagey about their meaning. But we as critics have to act responsibly when writing about literary texts in any good English essay or exam answer. We need to argue honestly, and sincerely – and not use what Wikipedia calls ‘weasel words’ or hedging expressions.

So, if nothing is utterly provable, all that remains is to make the strongest possible case you can with the evidence available. You do this, not only through marshalling the evidence in an effective way, but by writing in a confident voice when making your case. Fundamentally, ‘There is evidence to suggest that’ says more or less the same thing as ‘It can be argued’, but it foregrounds the evidence rather than the argument, so is preferable as a phrase.

This point might be summarised by saying: the best way to write a good English Literature essay is to be honest about the reading you’re putting forward, so you can be confident in your interpretation and use clear, bold language. (‘Bold’ is good, but don’t get too cocky, of course…)

5. Read the work of other critics.

This might be viewed as the Holy Grail of good essay-writing tips, since it is perhaps the single most effective way to improve your own writing. Even if you’re writing an essay as part of school coursework rather than a university degree, and don’t need to research other critics for your essay, it’s worth finding a good writer of literary criticism and reading their work. Why is this worth doing?

Published criticism has at least one thing in its favour, at least if it’s published by an academic press or has appeared in an academic journal, and that is that it’s most probably been peer-reviewed, meaning that other academics have read it, closely studied its argument, checked it for errors or inaccuracies, and helped to ensure that it is expressed in a fluent, clear, and effective way.

If you’re serious about finding out how to write a better English essay, then you need to study how successful writers in the genre do it. And essay-writing is a genre, the same as novel-writing or poetry. But why will reading criticism help you? Because the critics you read can show you how to do all of the above: how to present a close reading of a poem, how to advance an argument that is not speculative or tentative yet not over-confident, how to use evidence from the text to make your argument more persuasive.

And, the more you read of other critics – a page a night, say, over a few months – the better you’ll get. It’s like textual osmosis: a little bit of their style will rub off on you, and every writer learns by the examples of other writers.

As T. S. Eliot himself said, ‘The poem which is absolutely original is absolutely bad.’ Don’t get precious about your own distinctive writing style and become afraid you’ll lose it. You can’t gain a truly original style before you’ve looked at other people’s and worked out what you like and what you can ‘steal’ for your own ends.

We say ‘steal’, but this is not the same as saying that plagiarism is okay, of course. But consider this example. You read an accessible book on Shakespeare’s language and the author makes a point about rhymes in Shakespeare. When you’re working on your essay on the poetry of Christina Rossetti, you notice a similar use of rhyme, and remember the point made by the Shakespeare critic.

This is not plagiarising a point but applying it independently to another writer. It shows independent interpretive skills and an ability to understand and apply what you have read. This is another of the advantages of reading critics, so this would be our final piece of advice for learning how to write a good English essay: find a critic whose style you like, and study their craft.

If you’re looking for suggestions, we can recommend a few favourites: Christopher Ricks, whose The Force of Poetry is a tour de force; Jonathan Bate, whose The Genius of Shakespeare , although written for a general rather than academic audience, is written by a leading Shakespeare scholar and academic; and Helen Gardner, whose The Art of T. S. Eliot , whilst dated (it came out in 1949), is a wonderfully lucid and articulate analysis of Eliot’s poetry.

James Wood’s How Fiction Works is also a fine example of lucid prose and how to close-read literary texts. Doubtless readers of Interesting Literature will have their own favourites to suggest in the comments, so do check those out, as these are just three personal favourites. What’s your favourite work of literary scholarship/criticism? Suggestions please.

Much of all this may strike you as common sense, but even the most commonsensical advice can go out of your mind when you have a piece of coursework to write, or an exam to revise for. We hope these suggestions help to remind you of some of the key tenets of good essay-writing practice – though remember, these aren’t so much commandments as recommendations. No one can ‘tell’ you how to write a good English Literature essay as such.

But it can be learned. And remember, be interesting – find the things in the poems or plays or novels which really ignite your enthusiasm. As John Mortimer said, ‘The only rule I have found to have any validity in writing is not to bore yourself.’

Finally, good luck – and happy writing!

And if you enjoyed these tips for how to write a persuasive English essay, check out our advice for how to remember things for exams and our tips for becoming a better close reader of poetry .

Discover more from Interesting Literature

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Type your email…

30 thoughts on “How to Write a Good English Literature Essay”

You must have taken AP Literature. I’m always saying these same points to my students.

I also think a crucial part of excellent essay writing that too many students do not realize is that not every point or interpretation needs to be addressed. When offered the chance to write your interpretation of a work of literature, it is important to note that there of course are many but your essay should choose one and focus evidence on this one view rather than attempting to include all views and evidence to back up each view.

Reblogged this on SocioTech'nowledge .

Not a bad effort…not at all! (Did you intend “subject” instead of “object” in numbered paragraph two, line seven?”

Oops! I did indeed – many thanks for spotting. Duly corrected ;)

That’s what comes of writing about philosophy and the subject/object for another post at the same time!

Reblogged this on Scribing English .

- Pingback: Recommended Resource: Interesting Literature.com & how to write an essay | Write Out Loud

Great post on essay writing! I’ve shared a post about this and about the blog site in general which you can look at here: http://writeoutloudblog.com/2015/01/13/recommended-resource-interesting-literature-com-how-to-write-an-essay/

All of these are very good points – especially I like 2 and 5. I’d like to read the essay on the Martian who wrote Shakespeare’s plays).

Reblogged this on Uniqely Mustered and commented: Dedicate this to all upcoming writers and lovers of Writing!

I shall take this as my New Year boost in Writing Essays. Please try to visit often for corrections,advise and criticisms.

Reblogged this on Blue Banana Bread .

Reblogged this on worldsinthenet .

All very good points, but numbers 2 and 4 are especially interesting.

- Pingback: Weekly Digest | Alpha Female, Mainstream Cat

Reblogged this on rainniewu .

Reblogged this on pixcdrinks .

- Pingback: How to Write a Good English Essay? Interesting Literature | EngLL.Com

Great post. Interesting infographic how to write an argumentative essay http://www.essay-profy.com/blog/how-to-write-an-essay-writing-an-argumentative-essay/

Reblogged this on DISTINCT CHARACTER and commented: Good Tips

Reblogged this on quirkywritingcorner and commented: This could be applied to novel or short story writing as well.

Reblogged this on rosetech67 and commented: Useful, albeit maybe a bit late for me :-)

- Pingback: How to Write a Good English Essay | georg28ang

such a nice pieace of content you shared in this write up about “How to Write a Good English Essay” going to share on another useful resource that is

- Pingback: Mark Twain’s Rules for Good Writing | Interesting Literature

- Pingback: How to Remember Things for Exams | Interesting Literature

- Pingback: Michael Moorcock: How to Write a Novel in 3 Days | Interesting Literature

- Pingback: Shakespeare and the Essay | Interesting Literature

A well rounded summary on all steps to keep in mind while starting on writing. There are many new avenues available though. Benefit from the writing options of the 21st century from here, i loved it! http://authenticwritingservices.com

- Pingback: Mark Twain’s Rules for Good Writing | Peacejusticelove's Blog

Comments are closed.

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Continue reading

Anthony Cockerill

| Writing | The written word | Teaching English |

How to write great English literature essays at university

Essential advice on how to craft a great english literature essay at university – and how to avoid rookie mistakes..

If you’ve just begun to study English literature at university, the prospect of writing that first essay can be daunting. Tutors will likely offer little in the way of assistance in the process of planning and writing, as it’s assumed that students know how to do this already. At A-level, teachers are usually very clear with students about the Assessment Objectives for examination components and centre-assessed work, but it can feel like there’s far less clarity around how essays are marked at university. Furthermore, the process of learning how to properly reference an essay can be a steep learning curve.

But essentially, there are five things you’re being asked to do: show your understanding of the text and its key themes, explore the writer’s methods, consider the influence of contextual factors that might influence the writing and reading of the text, read published critical work about the text and incorporate this discourse into your essay, and finally, write a coherent argument in response to the task.

With advice from English teachers, HE tutors and other people who’ve been there and done it, here are the most crucial things to remember when planning and writing an essay.

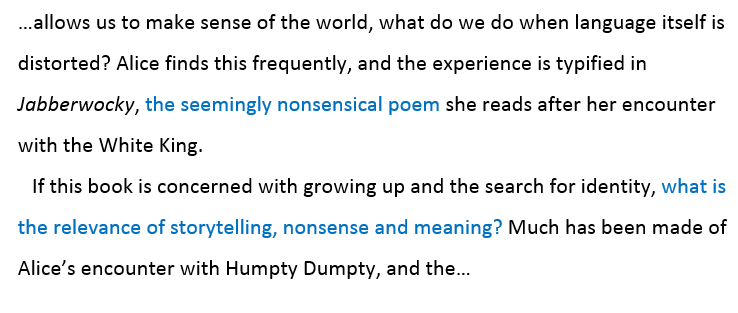

Read around the subject and let your argument evolve.

‘One of the big step-ups from A-level, where students might only have had to deal with critical material as part of their coursework, is the move toward engaging with the critical debate around a text.’

Reading around the task and making notes is all important. Get familiar with the reading list. Become adept at searching for critical material in books and articles that’s not on the reading list. Talk with the librarian. Make sure you can find your way around the stacks. Get log-ins for the various databases of online criticism, such as the MLA International Bibliography .

‘Tutors are looking for flair… for students to be nuanced and creative with their ideas as opposed to reproducing the same criticism that others already have.’

When reading, keep notes, make summaries and write down useful quotations. Make sure you keep track of what you’ve read as you go. Note the publication details (author, publisher, year and place of publication). If you write down a quotation, note the page number. This will make dealing with citations and writing your bibliography much easier later on, as there’s nothing more annoying than getting to the end of the first draft of your essay and realising you’ve no idea which book or article a quote came from or which page it was on.

‘The more I read, the sharper my own writing style became because I developed an opinion of the writing style I liked and I had a clear sense of the subject matter that I was discussing.’

‘Don’t wing the reading. Or the thinking. Crap writing emerges from style over substance.’

Get to grips with the question and plan a response.

‘Brain dump at the start in the form of a mind map. This will help you focus and relax. You can add to it as go along and can shape it into a brief plan.’

Before writing a single word, brainstorm. Do some free-thinking. Get your ideas down on paper or sticky notes. Cross things out; refine. Allow your planning to be led by ideas that support your argument.

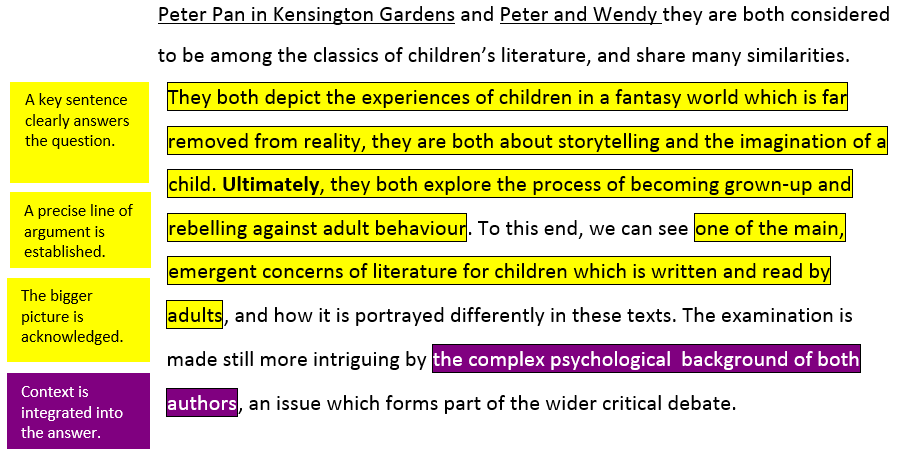

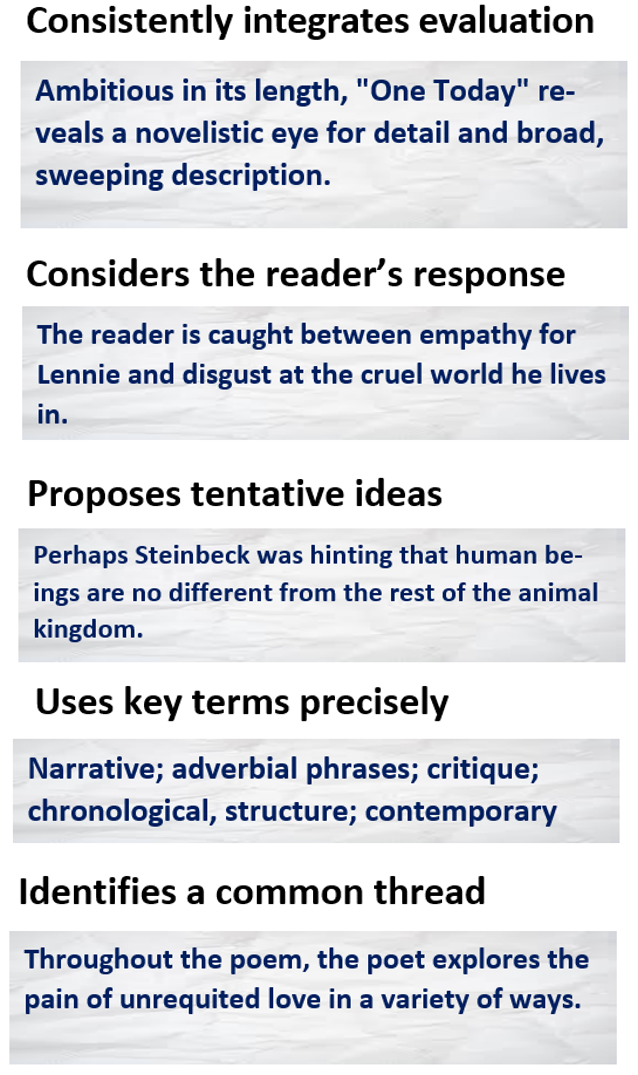

Use different colour-coded sticky notes for your planning. In the example below, the student has used yellow sticky notes for ideas, blue for language, structure and methods, purple for context and green for literary criticism, which makes planning the sequence of the essay much easier.

Structure and sequence your ideas

‘Make your argument clear in your opening paragraph, and then ensure that every subsequent paragraph is clearly addressing your thesis.’

Plan the essay by working out a sequence of your ideas that you believe to be the most compelling. Allow your ideas to serve as structural signposts. Augment these with relevant criticism, context and focus on language and style.

‘Read wide and look at different pieces of criticism of a particular work and weave that in with your own interpretation of said work.’

Write a great introduction.

‘By the end of the first paragraph, make sure you have established a very clear thesis statement that outlines the main thrust of the essay.’

Your introduction should make your argument very clear. It’s also a chance to establish working definitions of any problematic terms and to engage with key aspects of the wider critical debate.

Get to grips with academic style and draft the essay

‘[Write with] an ‘exploratory’ tone rather than ‘dogmatic’ one.’

Academic writing is characterised by argument, analysis and evaluation. In an earlier post , I explored how students in high school might improve their analytical writing by adopting three maxims. These maxims are just as helpful for undergraduates. Firstly, aim for precise, cogent expression. Secondly, deliver an individual response supported by your reading – and citing – of published literary criticism. Thirdly, work on your personal voice. In formal analytical writing such as the university essay, your personal voice might be constrained rather more than it would be in a blog or a review, but it must nonetheless be exploratory in tone. Tentativity can be an asset as it suggests appreciation of nuances and alternative ways of thinking.

‘I got to grips with what was being asked of me by reading lots of literary criticism and becoming more familiar with academic writing conventions.’

Avoid unnecessary or clunky sign-post phrases such as ‘in this essay, I am going to…’ or ‘a further thing…’ A transition devices that can work really well is the explicit paragraph link, in which a motif or phrase in the last sentence of a paragraph is repeated in the first sentence of the next paragraph.

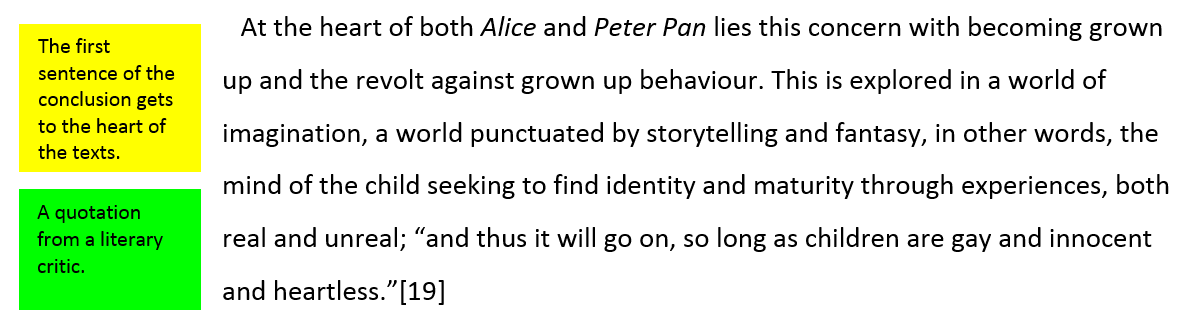

Write a killer conclusion

‘There is more emphasis on finding your own voice at university, something which in many ways is inhibited by Assessment Objectives at A-Level. I don’t think ‘good’ academic writing is necessarily taught very well in schools — at least from my experience.’

The conclusion is a really important part of your essay. It’s a chance to restate your thesis and to draw conclusions. You might achieve closure or instead, allude to interesting questions or ideas the essay has perhaps raised but not answered. You might synthesise your argument by exploring the key issue. You could zoom-out and explore the issue as part of a bigger picture.

Be meticulous in your referencing.

Having supported your argument with quotations from published critics, it’s important to be meticulous about how you reference these, otherwise you could be accused of plagiarism – passing someone else’s work off as your own. There are three broad ways of referencing: author-date, footnote and endnote. However, within each of these three approaches, there are specific named protocols. Most English literature faculties use either the MLA (Modern Languages Association of America) style or the Harvard style (variants of the author-date approach). It’s important to check what your faculty or department uses, learn how to use it (faculties invariably publish guidance, but ask if you’re unsure) and apply the rules meticulously.

‘Read your work aloud, slowly, sentence by sentence. It’s the best way to spot typos, and it allows you to hear what is awkward and/or ungrammatical. Then read the essay aloud again.’

Write with precision. Use a thesaurus to help you find the right word, but make sure you use it properly and in the right context. Read sentences back and prune unnecessary phrases or redundant words. Similarly, avoid words or phrases which might sound self-important or pompous.

Like those structural signposts that don’t really add anything, some phrases need to be omited, such as ‘many people have argued that…’ or ‘futher to the previous paragraph…’.

Finally, make sure the essay is formatted correctly. University departments are usually clear about their expectations, but font, size, and line spacing are usually stipulated along with any other information you’re expected to include in the essay’s header or footer. And don’t expect the proofing tool to pick up every mistake.

Featured image by Glenn Carstens-Peters on Unsplash

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- analytical writing

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

You are using an outdated browser. This site may not look the way it was intended for you. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience and security.

London School of Journalism

- Tel: +44 (0) 20 7432 8140

- [email protected]

- Student log in

Search courses

English literature essays, an english literature essay archive, written by our students, with subjects ranging from shakespeare to artistotle, and from dickens to hemingway, essay subjects in alphabetical order:.

- Aristotle: Poetics

Margaret Atwood

Margaret atwood 'gertrude talks back'.

- Matthew Arnold

John Bunyan: The Pilgrim's Progress and Geoffrey Chaucer: The Canterbury Tales

- Jonathan Bayliss

- Lewis Carroll, Samuel Beckett

- Saul Bellow and Ken Kesey

- Castiglione: The Courtier

- Joseph Conrad: Heart of Darkness

- Kate Chopin: The Awakening

- T S Eliot, Albert Camus

- Charles Dickens

- John Donne: Love poetry

- John Dryden: Translation of Ovid

- T S Eliot: Four Quartets

- Henry Fielding

- William Faulkner: Sartoris

- Graham Greene: Brighton Rock

- Ibsen, Lawrence, Galsworthy

- Jonathan Swift and John Gay

- Oliver Goldsmith

- Ernest Hemingway

- Nathaniel Hawthorne: The Scarlet Letter

Thomas Hardy: Tess of the d'Urbervilles

- Carl Gustav Jung

James Joyce: A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man

- Jon Jost: American independent film-maker

- Jamaica Kincaid, Merle Hodge, George Lamming

- Rudyard Kipling: Kim

- D. H. Lawrence: Women in Love

Henry Lawson: 'Eureka!'

- Ian McEwan: The Cement Garden

- Jennifer Maiden: The Winter Baby

- Machiavelli: The Prince

- Toni Morrison: Beloved and Jazz

R K Narayan

- R K Narayan: The English Teacher

- R K Narayan: The Guide

- Alexander Pope: The Rape of the Lock

- Brian Patten

- Harold Pinter

- Sylvia Plath and Alice Walker

Jean Rhys: Wide Sargasso Sea. Charlotte Bronte: Jane Eyre

- Edmund Spenser: The Faerie Queene

- Shakespeare: Antony and Cleopatra

- Shakespeare: Coriolanus

- Shakespeare: Hamlet

- Shakespeare: Measure for Measure

Shakespeare: Shakespeare's Women

Shakespeare: the winter's tale and the tempest.

- Shakespeare: Twelfth Night

- Sir Philip Sidney: Astrophil and Stella

- Tom Stoppard

William Styron: Sophie's Choice

- William Wordsworth

Miscellaneous

- Alice, Harry Potter and the computer game

Indian women's writing

- New York! New York!

- Photography and the New Native American Aesthetic

- Renaissance poetry

- Renaissance tragedy and investigator heroes

- Romanticism

- Studying English Literature

- The Age of Reason

- The author, the text, and the reader

- The Spy in the Computer

- What is literary writing?

- Margaret Atwood: Bodily Harm and The Handmaid's Tale

- Margaret Atwood 'Gertrude Talks Back'

- John Bunyan: The Pilgrim's Progress and Geoffrey Chaucer: The Canterbury Tales

- Thomas Hardy: Tess of the d'Urbervilles

- James Joyce: A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man: Will McManus

- James Joyce: A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man: Ian Mackean

- James Joyce: A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man: Ben Foley

- Henry Lawson: 'Eureka!'

- R K Narayan's vision of life

- Jean Rhys: Wide Sargasso Sea. Charlotte Bronte: Jane Eyre: Doubles

- Jean Rhys: Wide Sargasso Sea. Charlotte Bronte: Jane Eyre: Symbolism

- Shakespeare: Shakespeare's Women

- Shakespeare: The Winter's Tale and The Tempest

- William Wordsworth and Lucy

- Indian women's writing

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- How to write a literary analysis essay | A step-by-step guide

How to Write a Literary Analysis Essay | A Step-by-Step Guide

Published on January 30, 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on August 14, 2023.

Literary analysis means closely studying a text, interpreting its meanings, and exploring why the author made certain choices. It can be applied to novels, short stories, plays, poems, or any other form of literary writing.

A literary analysis essay is not a rhetorical analysis , nor is it just a summary of the plot or a book review. Instead, it is a type of argumentative essay where you need to analyze elements such as the language, perspective, and structure of the text, and explain how the author uses literary devices to create effects and convey ideas.

Before beginning a literary analysis essay, it’s essential to carefully read the text and c ome up with a thesis statement to keep your essay focused. As you write, follow the standard structure of an academic essay :

- An introduction that tells the reader what your essay will focus on.

- A main body, divided into paragraphs , that builds an argument using evidence from the text.

- A conclusion that clearly states the main point that you have shown with your analysis.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Step 1: reading the text and identifying literary devices, step 2: coming up with a thesis, step 3: writing a title and introduction, step 4: writing the body of the essay, step 5: writing a conclusion, other interesting articles.

The first step is to carefully read the text(s) and take initial notes. As you read, pay attention to the things that are most intriguing, surprising, or even confusing in the writing—these are things you can dig into in your analysis.

Your goal in literary analysis is not simply to explain the events described in the text, but to analyze the writing itself and discuss how the text works on a deeper level. Primarily, you’re looking out for literary devices —textual elements that writers use to convey meaning and create effects. If you’re comparing and contrasting multiple texts, you can also look for connections between different texts.

To get started with your analysis, there are several key areas that you can focus on. As you analyze each aspect of the text, try to think about how they all relate to each other. You can use highlights or notes to keep track of important passages and quotes.

Language choices

Consider what style of language the author uses. Are the sentences short and simple or more complex and poetic?

What word choices stand out as interesting or unusual? Are words used figuratively to mean something other than their literal definition? Figurative language includes things like metaphor (e.g. “her eyes were oceans”) and simile (e.g. “her eyes were like oceans”).

Also keep an eye out for imagery in the text—recurring images that create a certain atmosphere or symbolize something important. Remember that language is used in literary texts to say more than it means on the surface.

Narrative voice

Ask yourself:

- Who is telling the story?

- How are they telling it?

Is it a first-person narrator (“I”) who is personally involved in the story, or a third-person narrator who tells us about the characters from a distance?

Consider the narrator’s perspective . Is the narrator omniscient (where they know everything about all the characters and events), or do they only have partial knowledge? Are they an unreliable narrator who we are not supposed to take at face value? Authors often hint that their narrator might be giving us a distorted or dishonest version of events.

The tone of the text is also worth considering. Is the story intended to be comic, tragic, or something else? Are usually serious topics treated as funny, or vice versa ? Is the story realistic or fantastical (or somewhere in between)?

Consider how the text is structured, and how the structure relates to the story being told.

- Novels are often divided into chapters and parts.

- Poems are divided into lines, stanzas, and sometime cantos.

- Plays are divided into scenes and acts.

Think about why the author chose to divide the different parts of the text in the way they did.

There are also less formal structural elements to take into account. Does the story unfold in chronological order, or does it jump back and forth in time? Does it begin in medias res —in the middle of the action? Does the plot advance towards a clearly defined climax?

With poetry, consider how the rhyme and meter shape your understanding of the text and your impression of the tone. Try reading the poem aloud to get a sense of this.

In a play, you might consider how relationships between characters are built up through different scenes, and how the setting relates to the action. Watch out for dramatic irony , where the audience knows some detail that the characters don’t, creating a double meaning in their words, thoughts, or actions.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Your thesis in a literary analysis essay is the point you want to make about the text. It’s the core argument that gives your essay direction and prevents it from just being a collection of random observations about a text.

If you’re given a prompt for your essay, your thesis must answer or relate to the prompt. For example:

Essay question example

Is Franz Kafka’s “Before the Law” a religious parable?

Your thesis statement should be an answer to this question—not a simple yes or no, but a statement of why this is or isn’t the case:

Thesis statement example

Franz Kafka’s “Before the Law” is not a religious parable, but a story about bureaucratic alienation.

Sometimes you’ll be given freedom to choose your own topic; in this case, you’ll have to come up with an original thesis. Consider what stood out to you in the text; ask yourself questions about the elements that interested you, and consider how you might answer them.

Your thesis should be something arguable—that is, something that you think is true about the text, but which is not a simple matter of fact. It must be complex enough to develop through evidence and arguments across the course of your essay.

Say you’re analyzing the novel Frankenstein . You could start by asking yourself:

Your initial answer might be a surface-level description:

The character Frankenstein is portrayed negatively in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein .

However, this statement is too simple to be an interesting thesis. After reading the text and analyzing its narrative voice and structure, you can develop the answer into a more nuanced and arguable thesis statement:

Mary Shelley uses shifting narrative perspectives to portray Frankenstein in an increasingly negative light as the novel goes on. While he initially appears to be a naive but sympathetic idealist, after the creature’s narrative Frankenstein begins to resemble—even in his own telling—the thoughtlessly cruel figure the creature represents him as.

Remember that you can revise your thesis statement throughout the writing process , so it doesn’t need to be perfectly formulated at this stage. The aim is to keep you focused as you analyze the text.

Finding textual evidence

To support your thesis statement, your essay will build an argument using textual evidence —specific parts of the text that demonstrate your point. This evidence is quoted and analyzed throughout your essay to explain your argument to the reader.

It can be useful to comb through the text in search of relevant quotations before you start writing. You might not end up using everything you find, and you may have to return to the text for more evidence as you write, but collecting textual evidence from the beginning will help you to structure your arguments and assess whether they’re convincing.

To start your literary analysis paper, you’ll need two things: a good title, and an introduction.

Your title should clearly indicate what your analysis will focus on. It usually contains the name of the author and text(s) you’re analyzing. Keep it as concise and engaging as possible.

A common approach to the title is to use a relevant quote from the text, followed by a colon and then the rest of your title.

If you struggle to come up with a good title at first, don’t worry—this will be easier once you’ve begun writing the essay and have a better sense of your arguments.

“Fearful symmetry” : The violence of creation in William Blake’s “The Tyger”

The introduction

The essay introduction provides a quick overview of where your argument is going. It should include your thesis statement and a summary of the essay’s structure.

A typical structure for an introduction is to begin with a general statement about the text and author, using this to lead into your thesis statement. You might refer to a commonly held idea about the text and show how your thesis will contradict it, or zoom in on a particular device you intend to focus on.

Then you can end with a brief indication of what’s coming up in the main body of the essay. This is called signposting. It will be more elaborate in longer essays, but in a short five-paragraph essay structure, it shouldn’t be more than one sentence.

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is often read as a crude cautionary tale about the dangers of scientific advancement unrestrained by ethical considerations. In this reading, protagonist Victor Frankenstein is a stable representation of the callous ambition of modern science throughout the novel. This essay, however, argues that far from providing a stable image of the character, Shelley uses shifting narrative perspectives to portray Frankenstein in an increasingly negative light as the novel goes on. While he initially appears to be a naive but sympathetic idealist, after the creature’s narrative Frankenstein begins to resemble—even in his own telling—the thoughtlessly cruel figure the creature represents him as. This essay begins by exploring the positive portrayal of Frankenstein in the first volume, then moves on to the creature’s perception of him, and finally discusses the third volume’s narrative shift toward viewing Frankenstein as the creature views him.

Some students prefer to write the introduction later in the process, and it’s not a bad idea. After all, you’ll have a clearer idea of the overall shape of your arguments once you’ve begun writing them!

If you do write the introduction first, you should still return to it later to make sure it lines up with what you ended up writing, and edit as necessary.

The body of your essay is everything between the introduction and conclusion. It contains your arguments and the textual evidence that supports them.

Paragraph structure

A typical structure for a high school literary analysis essay consists of five paragraphs : the three paragraphs of the body, plus the introduction and conclusion.

Each paragraph in the main body should focus on one topic. In the five-paragraph model, try to divide your argument into three main areas of analysis, all linked to your thesis. Don’t try to include everything you can think of to say about the text—only analysis that drives your argument.

In longer essays, the same principle applies on a broader scale. For example, you might have two or three sections in your main body, each with multiple paragraphs. Within these sections, you still want to begin new paragraphs at logical moments—a turn in the argument or the introduction of a new idea.

Robert’s first encounter with Gil-Martin suggests something of his sinister power. Robert feels “a sort of invisible power that drew me towards him.” He identifies the moment of their meeting as “the beginning of a series of adventures which has puzzled myself, and will puzzle the world when I am no more in it” (p. 89). Gil-Martin’s “invisible power” seems to be at work even at this distance from the moment described; before continuing the story, Robert feels compelled to anticipate at length what readers will make of his narrative after his approaching death. With this interjection, Hogg emphasizes the fatal influence Gil-Martin exercises from his first appearance.

Topic sentences

To keep your points focused, it’s important to use a topic sentence at the beginning of each paragraph.

A good topic sentence allows a reader to see at a glance what the paragraph is about. It can introduce a new line of argument and connect or contrast it with the previous paragraph. Transition words like “however” or “moreover” are useful for creating smooth transitions:

… The story’s focus, therefore, is not upon the divine revelation that may be waiting beyond the door, but upon the mundane process of aging undergone by the man as he waits.

Nevertheless, the “radiance” that appears to stream from the door is typically treated as religious symbolism.

This topic sentence signals that the paragraph will address the question of religious symbolism, while the linking word “nevertheless” points out a contrast with the previous paragraph’s conclusion.

Using textual evidence

A key part of literary analysis is backing up your arguments with relevant evidence from the text. This involves introducing quotes from the text and explaining their significance to your point.

It’s important to contextualize quotes and explain why you’re using them; they should be properly introduced and analyzed, not treated as self-explanatory:

It isn’t always necessary to use a quote. Quoting is useful when you’re discussing the author’s language, but sometimes you’ll have to refer to plot points or structural elements that can’t be captured in a short quote.

In these cases, it’s more appropriate to paraphrase or summarize parts of the text—that is, to describe the relevant part in your own words:

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

The conclusion of your analysis shouldn’t introduce any new quotations or arguments. Instead, it’s about wrapping up the essay. Here, you summarize your key points and try to emphasize their significance to the reader.

A good way to approach this is to briefly summarize your key arguments, and then stress the conclusion they’ve led you to, highlighting the new perspective your thesis provides on the text as a whole:

If you want to know more about AI tools , college essays , or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

College essays

- Choosing Essay Topic

- Write a College Essay

- Write a Diversity Essay

- College Essay Format & Structure

- Comparing and Contrasting in an Essay

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

By tracing the depiction of Frankenstein through the novel’s three volumes, I have demonstrated how the narrative structure shifts our perception of the character. While the Frankenstein of the first volume is depicted as having innocent intentions, the second and third volumes—first in the creature’s accusatory voice, and then in his own voice—increasingly undermine him, causing him to appear alternately ridiculous and vindictive. Far from the one-dimensional villain he is often taken to be, the character of Frankenstein is compelling because of the dynamic narrative frame in which he is placed. In this frame, Frankenstein’s narrative self-presentation responds to the images of him we see from others’ perspectives. This conclusion sheds new light on the novel, foregrounding Shelley’s unique layering of narrative perspectives and its importance for the depiction of character.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2023, August 14). How to Write a Literary Analysis Essay | A Step-by-Step Guide. Scribbr. Retrieved September 3, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-essay/literary-analysis/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, how to write a thesis statement | 4 steps & examples, academic paragraph structure | step-by-step guide & examples, how to write a narrative essay | example & tips, what is your plagiarism score.

English Language and Literature

- Admissions Requirements

- Fees and Funding

- Studying at Oxford

Course overview

UCAS code: Q300 Entrance requirements: AAA Course duration: 3 years (BA)

Subject requirements

Required subjects: English Literature or English Language and Literature Recommended subjects: Not applicable Helpful subjects: A language, History

Other course requirements

Admissions tests: None Written Work: One piece

Admissions statistics*

Interviewed: 66% Successful: 23% Intake: 220 *3-year average 2021-23

Tel: +44 (0) 1865 271055 Email: [email protected]

Unistats information for this course can be found at the bottom of the page

Please note that there may be no data available if the number of course participants is very small.

About the course

The English Language and Literature course at Oxford is one of the broadest in the country, giving you the chance to study writing in English from its origins in Anglo-Saxon England to the present.

As well as British literature, you can study works written in English from other parts of the world, and some originally written in other languages, allowing you to think about literature in English in multilingual and global contexts across time.

The course allows you a considerable degree of choice, both in developing your personal interests across core papers, and in choosing a topic for your dissertation and for a special option in your final year.

Options have included:

- Literature and revolution

- Postcolonial literature

- Writing lives

- Film criticism.

Studying literature at Oxford involves the development of sophisticated reading skills and of an ability to place literary texts in their wider intellectual and historical contexts. It also requires you to:

- consider the critical processes by which you analyse and judge

- learn about literary form and technique

- evaluate various approaches to literary criticism and theory

- study the development of the English language.

The Oxford English Faculty is the largest English department in Britain. Students are taught in tutorials by an active scholar in their field, many of whom also give lectures to all students in the English Faculty. You will therefore have the opportunity to learn from a wide range of specialist teachers.

Library provision for English at Oxford is exceptionally good. All students have access to the Bodleian Library (with its extensive manuscript collection), the English Faculty Library, their own college libraries and a wide range of electronic resources.

In your first year, you will be introduced to the conceptual and technical tools used in the study of language and literature, and to a wide range of different critical approaches. At the same time, you will be doing tutorial work on early medieval literature, Victorian literature and literature from 1910 to the present.

In your second and third years, you will extend your study of English literary history in four more period papers ranging from late medieval literature to Romanticism. These papers are assessed by three-hour written examinations at the end of your third year. You will also produce:

- a portfolio of three essays on Shakespeare, on topics of your choice

- an extended essay (or occasionally an examination) relating to a special options paper, chosen from a list of around 25 courses

- and an 8,000-word dissertation on a subject of your choice.

Submitted work will constitute almost half of the final assessment for most students.

Alternatively, in the second and third years, you can choose to follow our specialist course in Medieval Literature and Language, with papers covering literature in English from 650-1550 along with the history of the English language up to 1800, with a further paper either on Shakespeare or on manuscript and print culture. Students on this course also take a special options paper and submit a dissertation on a topic of their choice.

Astrophoria Foundation Year

If you’re interested in studying English but your personal or educational circumstances have meant you are unlikely to achieve the grades typically required for Oxford courses, then choosing to apply for English with a Foundation Year might be the course for you.

Visit our Foundation Year course pages for more details.

'The real value of Oxford’s English course is its sheer scope, stretching from Beowulf to Virginia Woolf and beyond. Being guided through all the different ages of English literature means you explore periods and styles you may otherwise have rejected out of hand, discover brand new tastes, and even more levels to your love of literature! The ability to sit and read some of the greatest works of prose, poetry and performance in a city steeped in its own near-mythological wealth of history and beautiful architecture gives you a sense of being lost in your own fantasy, your own realm of turrets, tutors and texts.'

| 'I never really had any doubt I wanted to study English. The course here is so broad, I feel like I'm learning about things I would never have thought to do on my own. The best thing is probably the amount of freedom we get; we choose which lectures we want to go to, which texts to focus on, and mostly even choose our own essay questions. It means from the start you really get to explore your own interests, but your tutors make sure you're still preparing for broader exam questions through these.'

| '[The best thing about the course was] the freedom I had to direct my own studies, from choosing the books I wanted to write on, to developing my own specific area of focus within them. The course was a completely different learning experience from school because I was given the freedom to really work out what I thought about texts without having to worry about meeting assessment objectives or covering key themes. I've left Oxford knowing that I've really explored why I love literature so much and that I've contributed something individual to the study of literature, even if it ends up being just read by me.'

|

Unistats information

Discover Uni course data provides applicants with Unistats statistics about undergraduate life at Oxford for a particular undergraduate course.

Please select 'see course data' to view the full Unistats data for English Language and Literature.

Visit the Studying at Oxford section of this page for a more general insight into what studying here is likely to be like.

A typical week

Although details of practice vary from college to college, most students will have one or two tutorials (usually two students and a tutor) and one or two classes (in groups of around 8 to 10) each week. A tutorial usually involves discussion of an essay, which you will have produced based on your own reading and research that week. You will normally be expected to produce between eight and twelve pieces of written work each term. Most students will also attend several lectures each week.

Tutorials are usually 2-3 students and a tutor. Class sizes may vary depending on the options you choose. In college, there would usually be 6-12 students and in the department there would usually be no more than 15 students. There might be specific circumstances in which some classes contain around 20 students.

Most tutorials, classes, and lectures are delivered by staff who are tutors in their subject. Many are world-leading experts with years of experience in teaching and research. Some teaching may also be delivered by postgraduate students who are usually studying at doctoral level.

To find out more about how our teaching year is structured, visit our Academic Year page.

Course structure

| Four papers are taken: | Three written papers form the First University Examination, together with a submitted portfolio of two essays for Introduction to English language and literature. All exams must be passed, but marks do not count towards the final degree. |

| 1800 |

| More information on current options is available on the . | All period papers will be examined by final written examinations at the end of the third year. Most students will submit one extended essay for Special options, due in at the end of the first term; dissertation and portfolio for Shakespeare/The material text, due during the second term. |

The content and format of this course may change in some circumstances. Read further information about potential course changes .

Academic Requirements

| Requirement |

|---|---|

| AAA |

| AA/AAB |

| 38 (including core points) with 666 at HL |

| View information on , and . |

Wherever possible, your grades are considered in the context in which they have been achieved.

Read further information on how we use contextual data .

Subject requirements

| Candidates are expected to have English Literature, or English Language and Literature to A-level, Advanced Higher, Higher Level in the IB or any other equivalent. | |

| A language or History can be helpful to students in completing this course, although they are not required for admission. |

If a practical component forms part of any of your science A‐levels used to meet your offer, we expect you to pass it.

If English is not your first language you may also need to meet our English language requirements .

Please note that creative writing qualifications, regardless of awarding body, are not accepted and will not help you meet the academic requirements for this course.

If your personal or educational circumstances have meant you are unlikely to achieve the grades listed above for undergraduate study, but you still have a strong interest in the subject, then applying for English with a Foundation Year might be right for you.

Visit the Foundation Year course pages for more details of academic requirements and eligibility.

All candidates must follow the application procedure as shown on our Applying to Oxford pages.

The following information gives specific details for students applying for this course.

Admissions test

You do not need to take a written test as part of an application for this course.

Written work

As part of your application, you must send us a sample of your written work. If you are at school or college, this essay should be: You are welcome to send us any English Literature work that meets the requirements listed above. This could be a timed essay, a critical commentary, or an excerpt of your coursework or EPQ. Work can be handwritten or typed – either is fine. When you send us your work, please be sure to include a cover sheet. On the cover sheet you should describe the circumstances under which your work was produced. You and your teacher must both fill in this form. Tutors will take into account the information you give on your cover sheet when assessing your work. You’re welcome to submit an excerpt from a longer piece if you think it represents your best work. If so, please add a note on the cover sheet to explain the context of the excerpt. If you are a post-qualification or mature applicant, you can decide (although it is not necessary) to produce a new piece of work, as you may want to give a clearer reflection of your current abilities. We understand that this means it may not be possible to have this piece of work marked, so please use the cover sheet to detail the circumstances in which the work was produced. For full guidance on , please visit the English website. | |

10 November 2024 |

Visit our written work page for general guidance and to download the cover sheet.

What are tutors looking for?

Successful candidates will give evidence of wide, engaged, and thoughtful reading.

Written work helps us to gauge your analytical skills and your writing.

Interviews allow us to explore your enthusiasm for literature, your response to new ideas and information and your capacity for independent thought. We are not looking for any particular reading, or particular answers: we are interested in your ideas and in how you engage with literature.

Shortlisted candidates may also be asked to discuss an unseen piece of prose or verse given to you before or in the interview. Tutors appreciate that you may be nervous, and will try to put you at ease.

Visit the English website for more detail on the selection criteria for this course.

Our students go on to succeed in a very wide range of careers: the analytical and communication skills that develop during this course equip them for many different paths.

Popular careers and fields include:

- advertising

- librarianship

- public relations

- further research

- management consultancy

The Telling Our Stories Better project ran throughout 2021, bringing together alumni and current students of the English Faculty to talk about their time at Oxford and their career paths. Led by Dr Sophie Ratcliffe and Dr Ushashi Dasgupta , and managed by Dr Dominique Gracia, Stories aims to challenge misconceptions about who studies English and the career paths they take.

We don't want anyone who has the academic ability to get a place to study here to be held back by their financial circumstances. To meet that aim, Oxford offers one of the most generous financial support packages available for UK students and this may be supplemented by support from your college.

Please note that for full-time Home undergraduate students, current university policy is to charge fees at the level of the cap set by the government. The cap is currently set at £9,250 in 2024/25 and this has been included below as the guide annual course fee for courses starting in 2025. However, this page will be updated once the government has confirmed course fee information for full-time Home undergraduates starting courses in 2025. For details of annual increases, please see our guidance on likely increases to fees and charges .

| Home | £9,250 |

| Overseas | £41,130 |

Further details about fee status eligibility can be found on the fee status webpage.

For more information please refer to our course fees page . Fees will usually increase annually. For details, please see our guidance on likely increases to fees and charges.

Living costs

Living costs at Oxford might be less than you’d expect, as our world-class resources and college provision can help keep costs down.

Living costs for the academic year starting in 2025 are estimated to be between £1,425 and £2,035 for each month you are in Oxford. Our academic year is made up of three eight-week terms, so you would not usually need to be in Oxford for much more than six months of the year but may wish to budget over a nine-month period to ensure you also have sufficient funds during the holidays to meet essential costs. For further details please visit our living costs webpage .

- Financial support

Home | A tuition fee loan is available from the UK government to cover course fees in full for Home (UK, Irish nationals and other eligible students with UK citizens' rights - see below*) students undertaking their first undergraduate degree**, so you don’t need to pay your course fees up front. In 2025 Oxford is offering one of the most generous bursary packages of any UK university to Home students with a family income of around £50,000 or less, with additional opportunities available to UK students from households with incomes of £32,500 or less. The UK government also provides living costs support to Home students from the UK and those with settled status who meet the residence requirements. *For courses starting on or after 1 August 2021, the UK government has confirmed that EU, other EEA, and Swiss Nationals will be eligible for student finance from the UK government if they have UK citizens’ rights (i.e. if they have pre-settled or settled status, or if they are an Irish citizen covered by the Common Travel Area arrangement). The support you can access from the government will depend on your residency status. . |

Islands | Islands students are entitled to different support to that of students from the rest of the UK. Please refer the links below for information on the support to you available from your funding agency: |

Overseas | Please refer to the "Other Scholarships" section of our . |

**If you have studied at undergraduate level before and completed your course, you will be classed as an Equivalent or Lower Qualification student (ELQ) and won’t be eligible to receive government or Oxford funding

Fees, Funding and Scholarship search

Additional Fees and Charges Information for English Language and Literature

There are no compulsory costs for this course beyond the fees shown above and your living costs.

Contextual information

Unistats course data from Discover Uni provides applicants with statistics about a particular undergraduate course at Oxford. For a more holistic insight into what studying your chosen course here is likely to be like, we would encourage you to view the information below as well as to explore our website more widely.

The Oxford tutorial

College tutorials are central to teaching at Oxford. Typically, they take place in your college and are led by your academic tutor(s) who teach as well as do their own research. Students will also receive teaching in a variety of other ways, depending on the course. This will include lectures and classes, and may include laboratory work and fieldwork. However, tutorials offer a level of personalised attention from academic experts unavailable at most universities.

During tutorials (normally lasting an hour), college subject tutors will give you and one or two tutorial partners feedback on prepared work and cover a topic in depth. The other student(s) in your tutorials will be doing the same course as you. Such regular and rigorous academic discussion develops and facilitates learning in a way that isn’t possible through lectures alone. Tutorials also allow for close progress monitoring so tutors can quickly provide additional support if necessary.

Read more about tutorials and an Oxford education

College life

Our colleges are at the heart of Oxford’s reputation as one of the best universities in the world.

- At Oxford, everyone is a member of a college as well as their subject department(s) and the University. Students therefore have both the benefits of belonging to a large, renowned institution and to a small and friendly academic community. Each college or hall is made up of academic and support staff, and students. Colleges provide a safe, supportive environment leaving you free to focus on your studies, enjoy time with friends and make the most of the huge variety of opportunities.

- Porters’ lodge (a staffed entrance and reception)

- Dining hall

- Lending library (often open 24/7 in term time)

- Student accommodation

- Tutors’ teaching rooms

- Chapel and/or music rooms

- Green spaces

- Common room (known as the JCR).

- All first-year students are offered college accommodation either on the main site of their college or in a nearby college annexe. This means that your neighbours will also be ‘freshers’ and new to life at Oxford. This accommodation is guaranteed, so you don’t need to worry about finding somewhere to live after accepting a place here, all of this is organised for you before you arrive.

- All colleges offer at least one further year of accommodation and some offer it for the entire duration of your degree. You may choose to take up the option to live in your college for the whole of your time at Oxford, or you might decide to arrange your own accommodation after your first year – perhaps because you want to live with friends from other colleges.

- While college academic tutors primarily support your academic development, you can also ask their advice on other things. Lots of other college staff including welfare officers help students settle in and are available to offer guidance on practical or health matters. Current students also actively support students in earlier years, sometimes as part of a college ‘family’ or as peer supporters trained by the University’s Counselling Service.

Read more about Oxford colleges and how you choose

FIND OUT MORE

- Visit the faculty's website

Our 2024 undergraduate open days will be held on 26 and 27 June and 20 September.

Register to find out more about our upcoming open days.

English Faculty State School Open Day - 9 March 2024

RELATED PAGES

- Which Oxford colleges offer my course?

- Your academic year

- Foundation Year

Related courses

- English and Modern Languages

- Foundation Year (Humanities)

- History and English

- Classics and English

Feel inspired?

Why not have a look at the University's collection of literary resources on our Great Writers Inspire site .

You may also like to listen to radio programs such as BBC Radio 4's In Our Time , or one of the University's podcast series .

Alternatively magazines like The New Yorker , or journals like London Review of Books and The Paris Review , contain lots of fascinating long-read articles and essays.

Follow us on social media

Follow us on social media to get the most up-to-date application information throughout the year, and to hear from our students.

Supporting writers since 1790

Essay Guide

Our comprehensive guide to the stages of the essay development process. Back to Student Resources

Display Menu

Writing essays

- Essay writing

- Being a writer

- Thinking critically, thinking clearly

- Speaking vs. Writing

- Why are you writing?

- How much is that degree in the window?

- Academic writing

- Academic writing: key features

- Personal or impersonal?

- What tutors want – 1

- What tutors want – 2

- Be prepared to be flexible

- Understanding what they want – again

- Basic definitions

- Different varieties of essay, different kinds of writing

- Look, it’s my favourite word!

- Close encounters of the word kind

- Starting to answer the question: brainstorming

- Starting to answer the question: after the storm

- Other ways of getting started

- How not to read

- You, the reader

- Choosing your reading

- How to read: SQ3R

- How to read: other techniques

- Reading around the subject

- Taking notes

- What planning and structure mean and why you need them

- Introductions: what they do

- Main bodies: what they do

- Conclusions: what they do

- Paragraphs and links

- Process, process, process

- The first draft

- The second draft

- Editing – 1: getting your essay into shape

- Editing – 2: what’s on top & what lies beneath

- Are you looking for an argument?

- Simple definitions

- More definitions

- Different types of argument

- Sources & plagiarism

- Direct quotation, paraphrasing & referencing

- MLA, APA, Harvard or MHRA?

- Using the web

- Setting out and using quotations

- Recognising differences

- Humanities essays

- Scientific writing

- Social & behavioural science writing

- Beyond the essay

- Business-style reports

- Presentations

- What is a literature review?

- Why write a literature review?

- Key points to remember

- The structure of a literature review

- How to do a literature search

- Introduction

- What is a dissertation? How is it different from an essay?

- Getting it down on paper

- Drafting and rewriting

- Planning your dissertation

- Planning for length

- Planning for content

- Abstracts, tone, unity of style

- General comments

Welcome to Writing Essays, the RLF’s online guide to everything you wanted to know but were afraid to ask about writing undergraduate essays.

The guide is a toolbox of essay writing skills and resources that you can choose from to suit your particular needs. It combines descriptive and practical elements. That is, it tells you what things mean and what they are; and it uses examples to show you how they work.

Writing Essays takes you through the whole essay writing process – from preparing and planning to completion. Writing essays is structured progressively and I recommend that you use it in this way. However, you will see from the sidebar that the guide is divided into a number of main sections. Click on any one of these and you will see that it’s divided into shorter sections or subsections. So you can either read it straight through from start to finish or you can go straight to the area that’s most relevant to you.

Writing Essays does not cover every type of writing you will do at university but it does cover the principal types. So you will find guides to essay writing, dissertation writing, and report writing. You will also find a section dealing with the differences between writing for the humanities and writing for the sciences and social sciences. The information and guidelines in these sections will provide blueprints you can apply elsewhere.

You will see in the topbar options above that there is also a glossary of terms used in this guide; and a list of suggested further reading and online resources.

It is important to say here what Writing Essays does not do. It does not offer detailed advice on general study skills although it does cover some aspects of reading for writing and how to write a literature review. Unlike some guides, this one does not have anything to say about using computers except: use them, and save your work often.

Writing Essays does not deal with grammar and punctuation. This does not mean that I think that these things are not important, or that you don’t need to pay attention to them – all writers do. However, my experience of working with students has taught me two things. First, that the most common difficulties in writing essays are to do with areas like understanding the question and making a logical structure. Second, that when these difficulties are fixed, problems with grammar and punctuation are easier to see and fix.

Don’t just use Writing Essays once. Make it your constant reference point for writing essays. Make it the emergency number you dial if you breakdown or can’t get started!

English and Comparative Literary Studies

How to write an essay.

This handbook is a guide that I’m hoping will enable you. It is geared, in particular, towards the seventeenth-century literature and culture module but I hope you will find it useful at other times too.

I would like to stress, though, that it is not the only way to do things. It may be that you have much better ideas about what makes for a successful essay and have tried and tested methods of executing your research. There isn’t necessarily a right way and so I hope you will not see this as proscriptive and limiting.

You should talk to all your tutors about what makes for a good essay to get a sense of the different ways that you might construct an essay.

1. Essay writing (p.2)

2. Close reading (p. 4)

3. Research (p. 6)

4. Constructing an argument (p. 8)

5. Help with this particular assessment (p. 9)

6. Grade descriptions (p. 10)

1. ESSAY WRITING (and historicist writing in particular)

Essay writing has four stages: reading, planning, writing and proof-reading. Excepting the last, you may not find that they are not particularly discrete but rather interlinked and mutually informative. If any stage is skipped or done badly, though, it will impair your work.

1) Read the text and make sure you understand it. Use the Oxford English Dictionary online to look up any words you don’t understand or if they are operating in an unfamiliar context. Available on the Warwick web: http://www.oed.com

2) Do a close reading. Make a list technical features (cf. the page in this booklet entitled ‘close reading’; refer to the section on poetic form in the back of your Norton Anthologies pp. 2944-52). Ask yourself: ‘how does the text achieve its effects?’ Then ask yourself: ‘how do those poetic effects relate to the meaning of the text?’.