- Open access

- Published: 13 February 2024

Health impact of the Tajogaite volcano eruption in La Palma population (ISVOLCAN study): rationale, design, and preliminary results from the first 1002 participants

- María Cristo Rodríguez-Pérez ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0119-4276 1 ,

- Manuel Enrique Fuentes Ferrer 1 ,

- Luis D. Boada 2 , 3 ,

- Ana Delia Afonso Pérez 4 ,

- María Carmen Daranas Aguilar 5 ,

- Jose Francisco Ferraz Jerónimo 6 ,

- Ignacio García Talavera 1 , 7 ,

- Luis Vizcaíno Gangotena 5 ,

- Arturo Hardisson de la Torre 8 ,

- Katherine Simbaña-Rivera 2 , 9 &

- Antonio Cabrera de León 1 , 10

Environmental Health volume 23 , Article number: 19 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

1549 Accesses

1 Citations

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

The eruption of the Tajogaite volcano began on the island of La Palma on September 19, 2021, lasting for 85 days. This study aims to present the design and methodology of the ISVOLCAN (Health Impact on the Population of La Palma due to the Volcanic Eruption) cohort, as well as the preliminary findings from the first 1002 enrolled participants.

A prospective cohort study was conducted with random selection of adult participants from the general population, with an estimated sample size of 2600 individuals. The results of the first 857 participants are presented, along with a group of 145 voluntary participants who served as interveners during the eruption. Data on epidemiology and volcano exposure were collected, and participants underwent physical examinations, including anthropometry, blood pressure measurement, spirometry, and venous blood extraction for toxicological assessment.

In the general population ( n = 857), descriptive analysis revealed that the participants were mostly middle-aged individuals (50.8 ± 16.4), with a predominance of females. Before the eruption, the participants resided at a median distance of 6.7 km from the volcano in the Western region and 10.9 km in the Eastern region. Approximately 15.4% of the sample required evacuation, whose 34.8% returning to their homes on average after 3 months. A significant number of participants reported engaging in daily tasks involving cleaning of volcanic ash both indoors and outdoors. The most reported acute symptoms included ocular irritation, insomnia, mood disorders (anxiety-depression), and respiratory symptoms. Multivariate analysis results show that participants in the western region had a higher likelihood of lower respiratory tract symptoms (OR 1.99; 95% CI:1.33–2.99), depression and anxiety (OR 1.95; 95% CI:1.30–2.93), and insomnia (OR 2.03; 95% CI:1.33–3.09), compared to those in the eastern region.

The ongoing follow-up of the ISVOLCAN cohort will provide valuable insights into the short, medium, and long-term health impact related to the material emitted during the Tajogaite eruption, based on the level of exposure suffered by the affected population.

Peer Review reports

Approximately one billion people worldwide live within the influence zone of an active volcano, at about 100 km [ 1 ], and thus could be affected by the effects of an eruption at some point. On La Palma Island (Canary Islands, Spain), a volcanic eruption began on September 19, 2021, in the Valle de Aridane, lasting for 85 days and resulting in the formation of a new volcano named Tajogaite. The eruption generated a significant expulsion of volcanic ash and gas emissions, leading to days of highly unfavourable air quality with elevated toxicity levels in the breathable air [ 2 ].

Volcanic eruptions can have a wide range of deleterious effects on human health. Despite their often-short duration, the emission of toxic gases, particles, and ash deposits can persist in the local environment for years or even decades, being mobilized and redistributed by climatic factors or human activities [ 3 ]. Gases emitted during volcanic activity, such as CO and CO 2 , SO 2 , HCl, HF, H 2 S, radon, and permanent degassing, have the potential to impact human health [ 4 ]. There are several causes for degassing, both natural and anthropogenic sources whose contribute to air pollution. In La Palma, several years before the Tajogaite eruption, the concentration of CO 2 were recorded in Cumbre Vieja, beeing related, in much more amount, to anthropogenic and other natural sources than magmatic emissions, accounting for only 4% [ 5 ]. Acute and prolongated exposure of individuals to high concentrations of CO 2 is uncommon and incompatible with life. Nevertheless, long-term exposure occurs at low concentrations and outdoor is more frequent. In this context, physiological adaptation mechanisms are activated, promote oxidation followed by the release of proinflammatory cytokines; these mechanisms entail the development of a pro-inflammatory status and, consequently, the onset of diseases related to such conditions [ 6 ]. Particularly harmful to health is the atmospheric transformation of SO 2 and other gases into particulate matter (PM) [ 7 ]. This transformation process is influenced by various factors, including the emission plume’s characteristics and maturity, as well as meteorological variables such as humidity, solar radiation, and temperature [ 7 ].

Previous studies have demonstrated an increase in acute symptoms of ocular irritation and upper respiratory tract issues [ 8 ], as well as elevated respiratory morbidity and visits to hospital or primary care services due to exacerbation of respiratory pathologies associated with peaks in airborne emissions of these types of toxic gases or particles [ 3 , 9 , 10 ]. Many of these associations are independent of age, sex, education level, and smoking habits, exhibiting a dose-response gradient [ 11 ]. Furthermore, exposure has been linked to increased cardiovascular morbidity and all-cause mortality [ 12 ]. Few studies have assessed long-term chronic health effects, and the scarce longitudinal studies have methodological limitations due to the analysis of samples from hospitalized patients, low reliability of data sources in some countries, and short follow-up periods, often not exceeding six months. Consequently, longitudinal studies with extended follow-up periods in the general population are needed to analyse the occurrence of deleterious medium to long-term effects.

In January 2022, the ISVOLCAN study (Health Impact on the Population of La Palma caused by the Tajogaite Volcano Eruption) was started. This study involves the recruitment and follow-up of a cohort from the general adult population to assess the impact of the Tajogaite volcano eruption on the health of the population of the island. The purpose of this paper is to present the methodology of ISVOLCAN study and provide a preliminary analysis of the data obtained from the first 1002 enrolled participants.

Study design

This is an observational epidemiological study, using a prospective cohort design, targeting the general adult population residing in multiple municipalities on La Palma Island. Additionally, a group of volunteers from professional personnel with access to the exclusion zone or operations centre during the eruption (including civil protection workers, Spanish Security Forces, Emergency Services, scientists, etc.) was included. The study consists of two different stages: the first stage involved recruitment and baseline assessments conducted from 2022 to 2023, while the second phase will involve follow-up of the cohort at 2, 5, and 10-year intervals.

The study has obtained authorization from the health authorities and received a favorable decision from the Provincial Ethics and Medicines Committee (ref. CHUNSC_2021_88). Participants were required to provide written consent before being included in the study.

La Palma Island is a volcanic island located in the Atlantic Ocean, within the Canary Islands archipelago, Spain. Geographically, it is positioned at 28° 26’ N latitude and 14° 01’ W longitude from Madrid. Covering an approximate area of just over 700 km 2 , it ranks as the fifth-largest island in this archipelago [ 13 ]. The island counts with a population of 83,439 inhabitants [ 14 ]. Los Llanos de Aridane in the west side, is the city with highest population density, followed of Santa Cruz de La Palma. The Canarian Public Health System provides healthcare to the entire population through a hospital and a network of primary care health centres throughout the island.

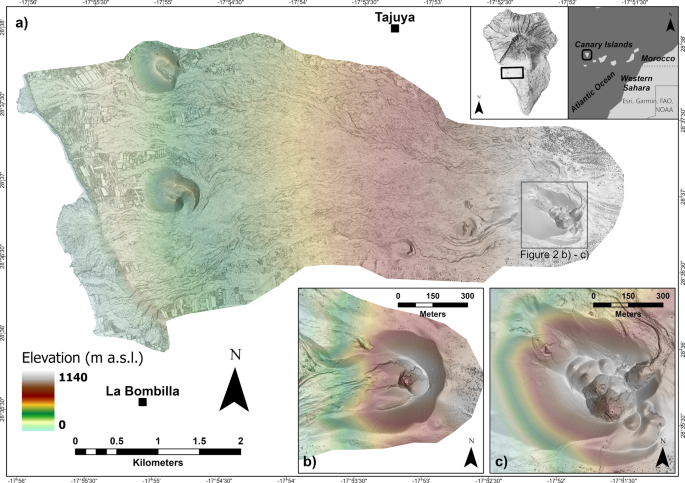

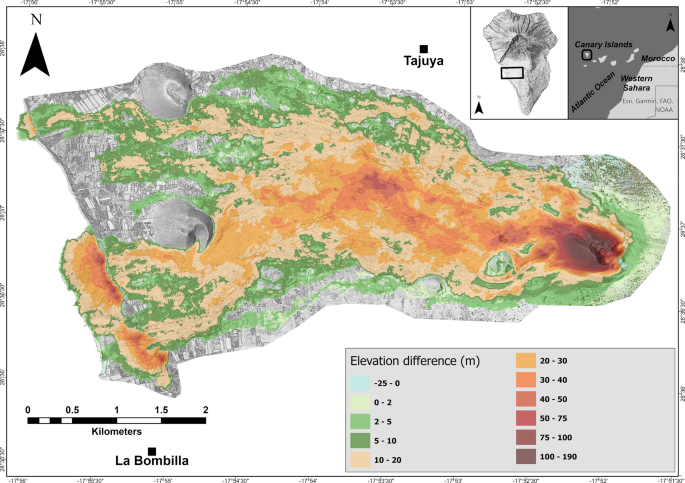

On September 19, 2021, the eruption started in the western region of La Palma Island, in Cabeza de Vaca area, on the western flank of the Cumbre Vieja ridge, belowing to the municipality of El Paso. This volcanic process persisted for 85 days until its conclusion on December 13 of the same year. It consisted in a long-lasting, hybrid eruption associated with multiple eruptive styles (effusive, lava fountains, ash emissions, strombolian explosions) with the formation of cones of various heights, widespread tephra blankets and extensive lava-flow fields and was characterized by simultaneous effusive and explosive activity [ 15 ]. The eruption affected the Valle de Aridane, which was greatly impacted by the lava flows, gases, and particulate matter emitted during the eruption. The newly formed volcano, named Tajogaite, reached a maximum altitude of 1131 m above sea level and extended 200 m from the pre-eruptive topography, with its base situated at 1080 m above sea level [ 16 ].

Subjects, sampling, inclusion and exclusion criteria

Participants from the general population.

The sample selection was conducted using a random, stratified approach based on age and gender groups, according to the 2020 municipal census data of the population residing in the western region (El Paso, Los Llanos, Tazacorte, and Puntagorda) and eastern region (Mazo, Santa Cruz de La Palma, and San Andrés y Sauces) of the island.

The sample was drawn from the health card registry of the Canarian Health Service, which is continuously updated and includes all individuals above the age of 18 who were residents on the island during the eruption and provided informed consent to participate in the study.

To ensure the achievement of the intended objectives, the population of the western region, closer to the eruption, was oversampled. The sample sizes for each municipality in the western region were as follows: Los Llanos de Aridane: 820; El Paso: 405; Tazacorte: 305; Puntagorda: 205. In contrast, for the eastern region, the sample sizes were 505 for Santa Cruz de La Palma, 205 for Mazo, and 155 for San Andrés y Sauces.

Highly exposed participants (intervening personnel)

Using a non-probabilistic convenience sampling method, participants in the study also included members of various professional and volunteer groups involved in different tasks related to the eruption and who had access to the volcano’s exclusion zone or operations centre. Although access to these areas was controlled and followed safety and protection measures, we expected that these participants from the different groups were highly exposed during their workdays throughout the nearly four-month duration of the eruption.

An initial sample size of 1207 persons was estimated (precision 3%, confidence level 95%) based on an expected prevalence of acute respiratory symptoms (the most frequently associated with such phenomena). Considering an anticipated participation rate in this type of study of 60–70% and a dropout rate during follow-up exceeding 30%, the sample was increased to 2600 individuals.

Recruitment and baseline assessment

In January 2022, telephone contact with the selected sample started. Those who agreed to participate in the study were administered an epidemiological questionnaire specifically designed for this purpose. The questionnaire was completed by Primary Care professionals, including both physicians and nurses, who were trained for this study. Subsequently, participants were scheduled to visit the health centres in the two regions for physical examinations, pulmonary function tests, and venous blood extraction, all conducted by qualified nursing staff.

An electronic questionnaire was designed in accordance with the recommendations of the International Volcanic Health Hazard Network (IVHHN), an organization under the World Health Organization (WHO), aimed at standardizing epidemiological protocols for assessing health effects in volcanic eruptions [ 17 ].

The questionnaire is available on the website of the study ( www.estudioisvolcan.com ) and included sociodemographic data (age, gender, employment status, occupation type, educational level), variables related to the level of exposure to the volcano (residence before and during the eruption, need for evacuation and subsequent return to the usual residence, access to exclusion zones, involvement in activities related to volcanic ash cleaning, daily hours spent in outdoor environments, and use of masks and eyeglasses for protection), pre-existing comorbidities (lung diseases, cardiovascular diseases, type 2 diabetes, blood hypertension, etc.), acute symptoms (cough, sneezing, wheezing, headache, fatigue, tearing, ocular irritation, etc.), suffering from any respiratory infection (flu, COVID 19 or cold) and visits to emergency services during the eruption, lifestyle factors (smoking habits and leisure-time physical activity). Additionally, the questionnaire included a shortened version of the scale for assessing post-traumatic stress disorder, adapted for the Spanish population [ 18 ].

During the visit to the health centre, measurements of weight, height, waist circumference, heart rate, and two separate blood pressure (separately by 10 min) were recorded. Additionally, a venous blood sample of approximately 20 mL was collected, divided into 4 tubes (2 tubes for complete blood count and 2 tubes for biochemistry), for the toxicological determination of persistent contaminants in whole blood and serum.

The tubes for complete blood were stored in a refrigerator at 4 °C, while the biochemistry tubes were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10–15 min, and then allowed to rest for 20–25 min until clot retraction. Daily, the samples were transported to the Laboratory of the University Hospital of La Palma and finally stored at the Research Unit of the Hospital Nuestra Señora de Candelaria in Tenerife at -80 °C for the sera and − 20 °C for the whole blood.

In the blood samples, organic contaminants, primarily polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), will be quantitatively determined due to their possible formation in eruptive processes and their known carcinogenic and teratogenic properties. Among them, the following will be determined: naphthalene, acenaphthene, acenaphthylene, fluorene, anthracene, phenanthrene, pyrene, fluoranthene, benzo(a)anthracene, chrysene, benzo(b)fluoranthene, benzo(k)fluoranthene, benzo(a)pyrene, benzo(ghi)perylene, indene(1,2,3,cd)pyrene, and dibenzo(ah)anthracene. Additionally, inorganic contaminants that may have been emitted in these eruptive processes will be quantified in whole blood. This includes: (a) trace elements (Co, Cr, Cu, Fe, Mn, Ni, Se, and Zn); (b) toxic elements listed in the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) inventory, such as Ag, Al, As, Be, Cd, Hg, Pb, Pd, Sb, Sr, Th, Ti, Tl, U, and V; (c) rare earth elements and other minor elements (Au, Bi, Ce, Dy, Eu, Er, Ga, Gd, Ho, In, La, Lu, Nb, Nd, Os, Pr, Pt, Ru, Sm, Sn, Tb, Ta, Tm, Y, and Yb). All these analyses will be performed using gas chromatography coupled with triple quadrupole mass spectrometry (GC-MS/MS) for organic contaminants and inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) for inorganic contaminants. The determinations will be carried out in the Toxicology laboratories of the two public universities of the Canary Islands.

Additionally, each participant underwent forced spirometry to measure lung function following the recommendations by the American Thoracic Society and the European Respiratory Society during the current SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV-1) and forced vital capacity (FVC), among other parameters, were measured. Spirometry tests were conducted using a portable spirometer acquired specifically for this study (Sibelmed, model Datospir Touch 3000).

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables will be presented with their distribution of absolute and relative frequencies. Quantitative variables that follow a normal distribution will be summarized using the mean and standard deviation (± SD), while those that do not follow this distribution will be presented with the median and interquartile range (IQR). To calculate the distance to the volcano, participant home coordinates during the eruption were obtained using the geodist command in STATA, and elevation was obtained using the elevatr Statistical package in R.

A comparison of the distribution of sociodemographic characteristics, variables related to the level of exposure during the eruption and previous comorbidities of the participants in the general population between the two regions (west and east) was performed. For categorical variables, the Chi-square test were used. Comparisons of means between two regions were performed by Student’s t-test if the variables followed a normal distribution, or by the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test for asymmetric variables. Finally, multivariate logistic regression models were performed to evaluate the independent effect of the place of residence (west vs. east) on acute symptomatology during the eruption. Those variables considered to be of interest were introduced as adjustment variables. The crude and adjusted odds ratios (OR) are presented together with their 95% confidence intervals (CI). Statistical significance was assumed as p < 0.05. Analyses were performed using the statistical package SPSS 26.0® (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Preliminary results of the descriptive analysis are presented for the first 1002 participants: 857 participants from the ISVOLCAN cohort, representing the general adult population of La Palma Island, and 145 intervening personnel who accessed the exclusion zone during the eruption.

Figure 1 shows the flowchart of the study sample. As of December 31, 2022, a total of 2355 phone calls were made to randomly selected individuals from the general population, and 857 participants were included (36.4% of those initially selected). In addition to the general population sample, the interveners ( n = 145) were mainly composed of members of State Security Forces, Emergency Services, and cleaning workers.

Flowchart of the ISVOLCAN study cohort until December 31, 2022

Table 1 describes the sociodemographic characteristics of the analysed sample from the general population. The mean age was 50.8 years (± 16.4), with a higher proportion of females. The majority had secondary education, and 20.8% of the sample were unemployed before the eruption; a similar situation was found in the two regions. During the eruption 662 (77.2%) resided in the western region and 198 (22.8%) in the eastern region. The group of participants from the western region presented a higher percentage of women and a higher percentage of unemployed people significantly.

In the interveners, the mean age was slightly younger (45.7 years (± 11.8)) with a predominance of males (supplemental Table 1 ).

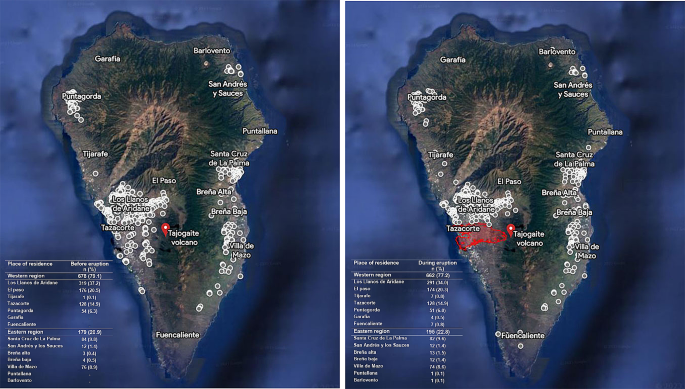

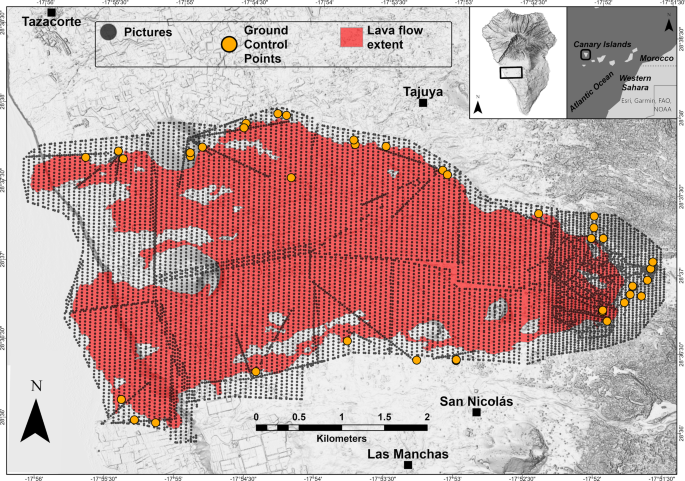

Figure 2 shows the geolocation of the ISVOLCAN cohort based on the coordinates of participants addresses before and during the eruption in the general population. It can be observed that during the eruption, there was a displacement of residents from the Valle de Aridane area to other parts of the island.

Place of residence of ISVOLCAN cohort participants: ( a ) before and ( b ) during Tajogaite volcano eruption

Characteristics related to exposure during the volcanic eruption in general population are described in Table 2 . The median distance from participants residence to the volcano during the eruption was 7.1 km (IQR:6.1–9.3); for the western region, it was 6.7 km (IQR: 4.9–7.3), while for the eastern region, it was 10.9 km (IQR: 9.3–12.7). Most of the population in the sample engaged in cleaning up volcanic ash, both inside and outside their homes, using tools with a high capacity for particle projection, such as brooms and blowers. During the eruption, 85% of the general population always used masks when outdoors, with FFP2 masks being the most used. In the bivariate analysis, it found that the location of the usual residence with less distance to the volcano and higher altitude, a more frequent cleaning of volcanic ash both inside and outside the homes and a more daily hours spent in outdoor environments were registered between participants from western region compared to those from the eastern one. The frequency of use of face masks and protective eyeglasses in outdoor environments did not differ between the two regions.

The intervining group showed a similar distribution to the general population regarding variables related to volcanic ash cleaning (location, tools used, and cleaning frequency), as well as mask usage frequency and type in outdoor environments (supplemental Table 2).

Table 3 shows baseline characteristics in general population related to lifestyle and pre-existing comorbidities before the eruption and use of healthcare resources and acute symptoms reported by participants during the eruption. The most prevalent pre-eruption comorbidities included blood hypertension (24.3%), depression and anxiety. The most frequently reported acute symptoms by the general population were eye irritation (45.9%), insomnia (44.9%), anxiety and depression (44.7%), and respiratory symptoms. In addition, 12.1% of the sample reported having an emergency visit at a hospital or primary care centres. The main reason for primary care visits was anxiety or depression, while hospital emergency visits were mainly due to osteomuscular traumas. Only 1.8% of the participants reported being hospitalized during the eruption, with surgical intervention being the primary reason. Participants from the western region compared to those from the eastern one were, significantly, more current smokers. Regarding acute symptomatology, western participants showed, in a statistically significant way, higher prevalence of nausea and vomiting, headache, lower respiratory tract symptoms (cough, dyspnea or wheezing), chest pain, insomnia, depression and anxiety, ocular, nasal and ear symptoms.

In the interveners, the acute symptoms reported during the eruption were like those of the general population, as well as the utilization of healthcare services. However, the percentage of hospitalizations was lower in this group (supplemental Table 3).

Table 4 shows the adjusted and unadjusted effect of region of residence during the volcano eruption (west/east) in general population on each of the most prevalent acute symptoms that showed statistically significant differences between the two regions. Age, gender, education level, employment, distance to the volcano, ash cleaning, type of cleaning tool used, daily hours in outdoor environments and type of smoker were entered as adjustment variables in all multivariate models. In addition, for the acute symptom lower respiratory tract symptoms, we adjusted for having suffered from any respiratory infection (influenza, COVID 19 or cold) during the months of the volcano eruption. Adjusted multivariate analysis results show that participants in the western region had a higher likelihood of lower respiratory tract symptoms (OR 1.99; 95% CI:1.33–2.99), depression and anxiety (OR 1.95; 95% CI:1.30–2.93) and insomnia (OR 2.03; 95% CI:1.33–3.09), compared to those in the eastern region.

This article presents the methodology of the ISVOLCAN study, as well as a descriptive analysis of the baseline characteristics of the first 1002 participants (857 participants from the general adult population of La Palma Island, and 145 interveners, potentially highly exposed).

After the initial telephone contact was established with the selected individuals from the general population of the island, an initial response rate of 36.4% was observed. Although a higher participation rate was expected, the conditions of uncertainty and vulnerability experienced by the population immediately after the eruption was extinguished and during the subsequent months, generated certain limitations. At the beginning of the ISVOLCAN study, part of the evacuated population was still displaced or involved in bureaucratic and administrative procedures related to the disaster.

As mentioned previously, epidemiological data for each participant were collected through a health questionnaire. Analysis of this data revealed that the participants had a mean age within the working-age range, with a predominance of women and most individuals who had completed secondary education. The recruited population mainly resided in the municipalities affected by the volcano, with the highest number of displacements during the eruption occurring among the inhabitants of Los Llanos de Aridane, which coincided with the movement of the lava flows. Regarding the intervining group, it was observed that they were younger and predominantly male, reflecting the male dominance in certain professions related to the field of public safety.

Factors related to the level of exposure of the participants were also considered in the analysis. It was observed that the proximity to the volcano was about 7 km, even less for the residents of Valle de Aridane. This proximity is unusual compared to other volcanic phenomena documented in scientific literature. For instance, in the case of Holuhraun, population centres were located at least 100 km away from the volcano, with only a few isolated farms found at a closer distance, approximately 70 km [ 19 ]. Another recent example concerns the Nyragongo or Nyamulagira volcanoes in the Republic of Congo, which affected a population of nearly one million people around the volcano, at approximately 15–30 km [ 20 ]. Therefore, in La Palma Island, the local population resided much closer to the eruption at the time compared to other mentioned populations.

Various health risks associated with the size of PM and their potential environmental impact on agriculture and water reservoirs have been reported [ 4 ]. Indeed, the deposition of several heavy metals, such as chromium and arsenic, in soils near volcanic eruptions has been documented, both of which have carcinogenic effects at certain levels [ 19 ]. In line with this, a very recent publication shows the chemical characterization of ash samples from Tajogaite eruption, founding that the most of the water-soluble compounds were SO 4 , F, Cl, Na, Ca, Ba, Mg and Zn; worryingly, the authors conclude that F and Cl concentration may exceed both the recommended levels for irrigation purpose and for health [ 21 ].

Moreover, the size of PM is of critical importance; particles smaller than 10 μm (PM 10 ) can penetrate and reach the alveolar region of the lungs [ 3 ], while those smaller than 2.5 μm (PM 2.5 ) may even cross the lung barrier and enter the bloodstream. There is an extensive body of evidence in relation to the health effects of the long-term exposure to PM 2.5 or lesser. The main reported effects are on all-causes and cause-specific mortality [ 22 ], incidence of cardiovascular or respiratory diseases [ 19 , 23 ], incidence of endocrine and metabolic disorders such as type 2 diabetes [ 24 ] and incidence of lung cancer among others, even at concentrations below current EU limit values and possibly WHO Air Quality Guidelines [ 25 ]. However, to the best of our knowledge, there are no published studies that analyze the potential effects of degassing exposure on the population of La Palma, neither before nor during the eruption.

During the Tajogaite eruption, daily air quality monitoring was carried out through eight stations located in different points of Valle de Aridane and the eastern region of the island. Based on these records, the average levels of SO 2 concentration in the island were recently published, and it was observed that the threshold recommended as safe by the European Commission was exceeded in the Valle area during 1 to 4% of the eruption duration. Furthermore, during the first month of the eruption, the threshold of 400 μm-3 was frequently exceeded, especially in the later stages of the phenomenon, in contrast to the emissions of particulate matter [ 2 , 26 ].

It is noteworthy to mention that, due to the recommendations of authorities and scientists, as well as the activation of volcanic emergency protocols, the integrity of the population was successfully safeguarded. However, it is reasonable to assume that the displacements of the evacuated population during the eruption could have had an impact on their health. Throughout the volcanic event, the island’s population received daily information about the necessary preventive measures in each municipality, based on air quality and the evolution of volcanic ash. In the case of our sample from the general population, 15.4% were evacuated during the eruption, and less than half of the evacuated individuals returned to their usual homes after an average of approximately 3 months.

On the other hand, exposure to volcanic gases and ash has been widely associated with increased respiratory morbidity and short-term irritation in the respiratory tract, ocular mucosa, and skin due to their chemical and mechanical irritant effects [ 3 , 19 , 27 ]. In the case of ISVOLCAN cohort participants, ocular and upper respiratory tract irritation were the most frequent acute symptoms. These findings are consistent with epidemiological studies conducted in the general population, both during the acute phase [ 28 ] and 6–9 months after exposure [ 11 ], as well as in highly exposed professionals [ 29 ]. Other studies evaluating the reasons and number of visits to hospital emergency departments have detected an increase in visits due to respiratory diseases and ocular disorders [ 30 , 31 ].

During the volcanic eruption, a significant proportion of the participants carried out ash cleaning tasks both indoors and outdoors, thereby increasing their exposure to the emitted material. As the eruption coincided with the second year of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, the population already had access to masks and was used to wearing them; the majority of the participants stated using masks when outdoors, with FPP2 masks being the most commonly used in these environments during the eruption, as they have demonstrated effectiveness in protecting against the inhalation of volcanic ash [ 32 ]. Certainly, it is imperative to maintain a surveillance over this excessive exposure in the coming years to comprehensively gauge potential medium and long-term repercussions. In the aftermath of the Tajogaite volcanic eruption, numerous supplementary investigations have been instigated, in addition to ISVOLCAN, with the aim of enhancing the monitoring of the health of the local population. Notably, the ASHES study is among these initiatives, with its principal focus being the assessment of respiratory health outcomes associated with exposure to volcanic emissions [ 33 ].

Moreover, prior investigations following volcanic eruptions have demonstrated a notable rise in the occurrence of psychiatric disorders within the general population [ 34 ]. Evacuated individuals, in particular, exhibited a pronounced prevalence of post-traumatic stress and depressive symptoms [ 35 ]. During the eruption period, nearly half of the individuals reported insomnia and symptoms indicative of mood disorders, such as anxiety or depression. Notably, those who had to undergo evacuation displayed a higher incidence of these symptoms. The eruption caused significant disruptions in the daily routines of the population in specific municipalities, especially those directly affected by evacuation orders.

The elevated prevalence of anxiety and depression can be related to several factors, including increased work demands during the eruption and the uncertainty concerning personal health, the well-being of others, property, and crop security, as well as the outlook for the future. Furthermore, given the substantial number of seismic events and the explosive nature of the eruption, it is plausible that these anxiety-related symptoms contributed to the substantial percentage of reported insomnia among the affected population.

Adjusted multivariate analysis results show that participants in the western region compared to those in the eastern region had a higher likelihood of lower respiratory tract symptoms, depression and anxiety, and insomnia. These results are similar to those found in the few epidemiological studies conducted in the general population that evaluate symptomatology, acute or short-term, during the eruption according to the level of exposure. These results are in concordance to previous evidence [ 11 , 36 ].

Furthermore, the recognition of volcanic eruptions as sources of toxic elements underscores the environmental exposure faced by populations residing in close proximity to these emission sites. Environmental studies conducted worldwide, including the Canary Islands, have consistently identified volcanic eruptions as significant contributors of inorganic elements known to be toxic to humans, such as Se, Cd, Pb and Hg [ 37 , 38 ]. Notably, recent findings from the ISVOLCAN study have documented elevated levels of Fe, Al, Ti, V, Ba, Pb, Mo, Co, and Rare Earths in banana crops on the island during the eruption period [ 39 ].

However, studies focused on monitoring toxin levels in populations affected by eruptions are limited, primarily due to the challenge of simultaneously quantifying these inorganic toxins in blood samples collected from affected individuals. Furthermore, the necessary analytical methods are mostly expensive, limiting their inclusion into epidemiological studies. In this context, our research team, as experts in toxicological analysis of both major inorganic and organic pollutants, is presently conducting determinations using venous blood samples from study participants, although results are pending.

The main limitation of the ISVOLCAN study, as is common in cohort studies, is its high cost, which is exacerbated in our case by logistical difficulties inherent in a fragmented territory like the Canary Islands, limiting the transfer of biological samples and human or material resources between islands. Additionally, while the participants were randomly selected from the general population, there may exist a selection bias if those who chose not to participate had some differential characteristics (e.g., older age, pre-existing health issues, etc.) compared to the participants, which could limit the detection of certain relevant associations.

Furthermore, the epidemiological data relies on self-reporting by the participants, which could introduce information biases affecting the validity of the results. Additionally, the high percentage of losses during follow-up, related to this type of design, could generate a survival bias. To address these concerns, several methodological strategies have been implemented. The sample size was increased to more than double the initial estimate, that is why recruitment and inclusion of participants are ongoing at this moment. Moreover, as a strength of the study, data collection started as soon as possible after the eruption was finished, carried out by personnel specially trained to ensure rigor and thoroughness in the process, following the recommendations of the IVHHN regarding epidemiological data records for such phenomena. Additionally, prior to analysis, the data undergo rigorous quality control and verification processes.

Given that the data come from a randomized sample of the general population of the island, followed over several years, this study will allow for the detection of causal associations. It is worth noting that the inclusion of interveners in the ISVOLCAN cohort provides a significant area of study since they can be considered as individuals with high prior exposure.

The ISVOLCAN study has been meticulously designed as a 10-year follow-up study aimed at assessing the medium to long-term health impact on the adult general population of La Palma Island following the recent eruption of the Tajogaite volcano. Despite currently being in a recruitment phase, the study has successfully completed several stages of biological sample collection and biomedical data gathering. Once the baseline measurements are finalized and toxicological determinations are conducted, data from over 2000 individuals with varying levels of exposure during the eruption are expected to be obtained. Lastly, in our knowledge this study is the first to publish data related to the short-term health impact on the population of La Palma following the eruption of the Tajogaite volcano.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are not openly available due to reasons of sensitivity and are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

Carbon monoxide

Carbon dioxide

Sulfur dioxide

Hydrogen chloride

Hydrogen fluoride

Hydrogen sulfide

Particulate matter

International Volcanic Health Hazard Network

World Health Organization

Primarily polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons

Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry

Standard deviation

Interquartile range

Particulate matter ≤ 2.5 μm

Particulate matter < 10 μm

Freire S, Florczyk AJ, Pesaresi M, Sliuzas R. An Improved Global Analysis of Population Distribution in proximity to active volcanoes, 1975–2015. ISPRS Int J Geo-Inf. 2019;8(8):341.

Article Google Scholar

Milford C, Torres C, Vilches J, Gossman AK, Weis F, Suárez-Molina D, et al. Impact of the 2021 La Palma volcanic eruption on air quality: insights from a multidisciplinary approach. Sci Total Environ. 2023;869:161652.

Article PubMed ADS CAS Google Scholar

Horwell CJ, Baxter PJ. The respiratory health hazards of volcanic ash: a review for volcanic risk mitigation. Bull Volcanol. 2006;69(1):1–24.

Article ADS Google Scholar

Hansell AL, Horwell CJ, Oppenheimer C. The health hazards of volcanoes and geothermal areas. Occup Environ Med. 2006;63(2):149–56.

Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar

Padrón E, Pérez N, Rodríguez F, Melián G, Hernández PA, Sumino H. Dynamics of diffuse carbon dioxide emissions from Cumbre Vieja volcano, La Palma, Canary Islands. Bull Volcanol. 2015;77:28.

Zappulla D. Environmental stress, erythrocyte dysfunctions, inflammation, and metabolic syndrome: adaptations to CO 2 increases? J Cardiometab Syndr. 2008;3(1):30–4.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Stewart C, Damby DE, Horwell CJ, Elias T, Ilyinskaya E, Tomašek I, et al. Volcanic air pollution and human health: recent advances and future directions. Bull Volcanol. 2021;84(1):11.

Gudmundsson G. Respiratory health effects of volcanic ash with special reference to Iceland. A review. Clin Respir J. 2011;5(1):2–9.

Higuchi K, Koriyama C, Akiba S. Increased mortality of respiratory diseases, including lung cancer, in the area with large amount of ashfall from Mount Sakurajima volcano. J Environ Public Health. 2012;2012:257831.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Longo BM, Yang W. Acute bronchitis and volcanic air pollution: a community-based cohort study at Kilauea Volcano, Hawai’i, USA. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2008;71(24):1565–71.

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Carlsen HK, Hauksdottir A, Valdimarsdottir UA, Gíslason T, Einarsdottir G, Runolfsson H, et al. Health effects following the Eyjafjallajökull volcanic eruption: a cohort study. BMJ Open. 2012;2(6):e001851.

Oudin A, Carlsen HK, Forsberg B, Johansson C. Volcanic Ash and Daily Mortality in Sweden after the Icelandic volcano eruption of May 2011. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2013;10(12):6909–19.

Instituto Geográfico Nacional. Instituto Geográfico Nacional - Servicio de Documentación. 2022 [cited 2023 Jul 26]. La Palma (Isla). Mapas topográficos. 1996. Available from: https://www.ign.es/web/catalogo-cartoteca/resources/html/017034.html .

Instituto Canario de Estadística ISTAC. Official Population Figures Referring to Revision of Municipal Register 1 January, 2022. Canary Islands Statistic Institute, Spain. [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2023 Sep 17]. Available from: http://www.gobiernodecanarias.org/istac/estadisticas/ .

Bonadonna C, Pistolesi M, Dominguez L, Freret-Lorgeril V, Rossi E, Fries A, et al. Tephra sedimentation and grainsize associated with pulsatory activity: the 2021 Tajogaite eruption of Cumbre Vieja (La Palma, Canary Islands, Spain). Front Earth Sci. 2023;11:1166073.

Gobierno de Canarias. PEVOLCA - Comité científico [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2023 Jul 28]. Available from: https://www.gobiernodecanarias.org/infovolcanlapalma/pevolca/ .

The International Volcanic Health Hazard Network (IVHHN). Standardized Epidemiological Study Protocol to Assess Short-term Respiratory and Other Health Impacts in Volcanic Eruptions [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2023 Jul 19]. Available from: https://www.ivhhn.org/uploads/IVHHN%20Basic%20Protocol.pdf .

Bobes J, Calcedo-Barba A, García M, François M, Rico-Villademoros F, González MP, et al. [Evaluation of the psychometric properties of the Spanish version of 5 questionnaires for the evaluation of post-traumatic stress syndrome]. Actas Esp Psiquiatr. 2000;28(4):207–18.

PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Carlsen HK, Ilyinskaya E, Baxter PJ, Schmidt A, Thorsteinsson T, Pfeffer MA, et al. Increased respiratory morbidity associated with exposure to a mature volcanic plume from a large Icelandic fissure eruption. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):2161.

Article PubMed PubMed Central ADS CAS Google Scholar

Michellier C, Katoto P, de Dramaix MC, Nemery M, Kervyn B. Respiratory health and eruptions of the Nyiragongo and Nyamulagira volcanoes in the Democratic Republic of Congo: a time-series analysis. Environ Health. 2020;19(1):62.

Ruggieri F, Forte G, Bocca B, Casentini B, Bruna Petrangeli A, Salatino A, Gimeno D. Potentially harmful elements released by volcanic ash of the 2021 Tajogaite eruption (Cumbre Vieja, La Palma Island, Spain): implications for human health. Sci Total Environ. 2023;905:167103.

Article PubMed ADS Google Scholar

Chen J, Hoek G. Long-term exposure to PM and all-cause and cause-specific mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ Int. 2020;143:105974.

Wolf K, Hoffmann B, Andersen ZJ, Atkinson RW, Bauwelinck M, Bellander T, et al. Long-term exposure to low-level ambient air pollution and incidence of stroke and coronary heart disease: a pooled analysis of six European cohorts within the ELAPSE project. Lancet Planet Health. 2021;5(9):e620–32.

Yang Z, Mahendran R, Yu P, Xu R, Yu W, Godellawattage S, Li S, Guo Y. Health effects of Long-Term exposure to ambient PM 2.5 in Asia-Pacific: a systematic review of Cohort studies. Curr Environ Health Rep. 2022;9(2):130–51.

Hvidtfeldt UA, Severi G, Andersen ZJ, Atkinson R, Bauwelinck M, Bellander T. Long-term low-level ambient air pollution exposure and risk of lung cancer - A pooled analysis of 7 European cohorts. Environ Int. 2021;146:106249.

Filonchyk M, Peterson MP, Gusev A, Hu F, Yan H, Zhou L. Measuring air pollution from the 2021 Canary Islands volcanic eruption. Sci Total Environ. 2022;849:157827.

Hansell A, Oppenheimer C. Health hazards from volcanic gases: a systematic literature review. Arch Environ Health. 2004;59(12):628–39.

Carlsen HK, Gislason T, Benediktsdottir B, Kolbeinsson TB, Hauksdottir A, Thorsteinsson T, et al. A survey of early health effects of the Eyjafjallajokull 2010 eruption in Iceland: a population-based study. BMJ Open. 2012;2(2):e000343.

Carlsen HK, Aspelund T, Briem H, Gislason T, Jóhannsson T, Valdimarsdóttir U, et al. Respiratory health among professionals exposed to extreme SO2 levels from a volcanic eruption. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2019;45(3):312–5.

Baxter PJ, Ing R, Falk H, French J, Stein GF, Bernstein RS, et al. Mount St Helens eruptions, May 18 to June 12, 1980. An overview of the acute health impact. JAMA. 1981;246(22):2585–9.

Lombardo D, Ciancio N, Campisi R, Di Maria A, Bivona L, Poletti V, et al. A retrospective study on acute health effects due to volcanic ash exposure during the eruption of Mount Etna (Sicily) in 2002. Multidiscip Respir Med. 2013;8(1):51.

Steinle S, Sleeuwenhoek A, Mueller W, Horwell CJ, Apsley A, Davis A, et al. The effectiveness of respiratory protection worn by communities to protect from volcanic ash inhalation. Part II: total inward leakage tests. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2018;221(6):977–84.

Ruano-Ravina A, Acosta O, Díaz Pérez D, Casanova C, Velasco V, Peces-Barba G, et al. A longitudinal and multidesign epidemiological study to analyze the effect of the volcanic eruption of Tajogaite volcano (La Palma, Canary Islands). The ASHES study protocol. Environ Res. 2023;216(Pt 2):114486.

Shore JH, Tatum EL, Vollmer WM. Evaluation of mental effects of disaster, Mount St. Helens eruption. Am J Public Health. 1986;76(3 Suppl):76–83.

Goto T, Wilson JP, Kahana B, Slane S. The Miyake Island Volcano Disaster in Japan: loss, uncertainty, and Relocation as predictors of PTSD and Depression. J App Soc Psychol. 2006;36(8):2001–26.

Shimizu Y, Dobashi K, Hisada T, Ono A, Todokoro M, Iijima H, et al. Acute impact of volcanic ash on asthma symptoms and treatment. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2007;20(2 Suppl 2):9–14.

Ilyinskaya E, Mason E, Wieser PE, Holland L, Liu EJ, Mather TA, et al. Rapid metal pollutant deposition from the volcanic plume of Kīlauea, Hawai’i. Commun Earth Environ. 2021;2(1):1–15.

Google Scholar

Rodríguez Martín JA, Nanos N, Miranda JC, Carbonell G, Gil L. Volcanic mercury in Pinus canariensis. Naturwissenschaften. 2013;100(8):739–47.

Rodríguez-Hernández A, Díaz-Díaz R, Zumbado M, Bernal-Suárez M, del Acosta-Dacal M, Macías-Montes A. Impact of chemical elements released by the volcanic eruption of La Palma (Canary Islands, Spain) on banana agriculture and European consumers. Chemosphere. 2022;293:133508.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors give special thanks to Marta Rodríguez Pérez for her invaluable contribution in the technical support of this study. She has managed the contacts with selected persons and scheduled participants. She also designed all the electronic documents to recording data from the participants and has carried out the data quality control of the database of the cohort. Many thanks too to the Primary Care health staff of La Palma, nurses and family physicians, around the island, for their help to disseminate the study and to administer epidemiological questionnaires to the participants.

Fundación Canaria Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria de Canarias (FIISC: ST22/07). Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Madrid (PI22/00395).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University Hospital Nuestra Señora de Candelaria and Primary Care Authority of Tenerife, Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Spain

María Cristo Rodríguez-Pérez, Manuel Enrique Fuentes Ferrer, Ignacio García Talavera & Antonio Cabrera de León

Toxicology Unit, Research Institute of Biomedical and Health Sciences (IUIBS), University of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria (ULPGC), Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain

Luis D. Boada & Katherine Simbaña-Rivera

Spanish Biomedical Research Centre in Physiopathology of Obesity and Nutrition (CIBERObn), Madrid, Spain

Luis D. Boada

Primary care health centre of Breña Alta. Health Services Authority of La Palma, Breña Alta, Spain

Ana Delia Afonso Pérez

University hospital of La Palma. Health Services Authority of La Palma, Breña Alta, Spain

María Carmen Daranas Aguilar & Luis Vizcaíno Gangotena

Primary care health centre of Breña Baja. Health Services Authority of La Palma, Breña Alta, Spain

Jose Francisco Ferraz Jerónimo

Respiratory Department, University Hospital Nuestra Señora de Candelaria., Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Spain

Ignacio García Talavera

Toxicology Department, Medical School, University of La Laguna, San Cristóbal de La Laguna, Spain

Arturo Hardisson de la Torre

Centro de Investigación para la Salud en América Latina (CISeAL), Facultad de Medicina, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador (PUCE), Quito, Ecuador

Katherine Simbaña-Rivera

Preventive Medicine Department, Medical School, University of La Laguna, San Cristóbal de La Laguna, Spain

Antonio Cabrera de León

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Conception and design: M.C.R.P, L.D.B, A.H.T, A.C.L, I.G.T. Study recruitment and sample processing: A.D.A.P, M.C.D.A, J.F.F.J, L.V.G. Samples management and analysis: I.G.T, L.D.B, A.H.T, L.V.G. Acquisition of epidemiological data: M.C.R.P, A.D.A.P, M.C.D.A, J.F.F.J. Complete data curation and analysed: M.C.R.P, M.E.F.F. Interpretation of the data: M.C.R.P, M.E.F.F, A.C.L, L.D.B, K.S.R. Draft the article: M.C.R.P, M.E.F.F, A.C.L, L.D.B, K.S.R. All authors revised and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to María Cristo Rodríguez-Pérez .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication.

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1

Rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Rodríguez-Pérez, M.C., Ferrer, M.E.F., Boada, L.D. et al. Health impact of the Tajogaite volcano eruption in La Palma population (ISVOLCAN study): rationale, design, and preliminary results from the first 1002 participants. Environ Health 23 , 19 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-024-01056-4

Download citation

Received : 19 September 2023

Accepted : 20 January 2024

Published : 13 February 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-024-01056-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Volcanic eruptions

- Epidemiology and Public Health

- Morbidity Associated with volcanic eruption

- Mortality Associated with volcanic eruption

- Non-anthropogenic toxic contaminants

Environmental Health

ISSN: 1476-069X

- General enquiries: [email protected]

UCL Earth Sciences

- The Department

- Equality (EDI)

Responding to a volcanic emergency on La Palma.

12 December 2021

Contributing to the eruption monitoring efforts during an ongoing volcanic emergency is a fascinating yet deeply humbling experience. You have the unique opportunity to observe volcanic phenomena up close and may learn more in a day than you would otherwise learn in a year!

Caption: Multiple aligned vents were active during the Cumbre Vieja eruption, each exhibiting very different eruptive styles (from ash-rich and explosive, to ash-poor and effusive) and characterised by contrasting volcanic gas compositions.

Contributing to the eruption monitoring efforts during an ongoing volcanic emergency is a fascinating yet deeply humbling experience. You have the unique opportunity to observe volcanic phenomena up close (and may learn more in a day than you would otherwise learn in a year!) and yet you are acutely aware of how devasting these events are for the local communities, who will be rebuilding their lives for long after the eruption is over. A new eruption began at the Cumbre Vieja volcanic system on La Palma on 19 September. To date, lava flows have covered ~10 km 2 of land area, destroying almost 3000 homes and displacing ~7500 people. Volcanic ash has been deposited over much of the island of La Palma, causing continuous societal disruption and posing an air quality hazard. I, along with many in the volcanological community, had been tracking the elevated seismicity and ground deformation in monitoring data with concern and was in discussion with INVOLCAN (the local volcanological monitoring institute in the Canary Islands) about how I might contribute to the geochemical monitoring of the emitted volcanic gases, should an eruption occur. Together with colleagues from the University of Palermo and University of Bristol, we arrived in La Palma soon after the eruption began.

Caption: Rapid processing of new gas data in the field following a UAS flight into the volcanic plume. We provided daily data reports to INVOLCAN.

Our group’s contribution to the eruption response included aerial measurements of the volcanic gas and aerosol chemistry. For this we used unoccupied aircraft systems (UAS)— or drones—to allow us to sample the gas plume much closer than would be otherwise safely accessible. The intensity of the eruption took many researchers by surprise, with vigorous lava fountaining activity from multiple vents feeding energetic, ash-rich eruption columns up to 5-7 km into the atmosphere. Alongside remote sensing observations conducted by colleagues, we acquired in-situ measurements of plume chemistry using a MultiGAS instrument (both ground-based and flown on a UAS), which analyses concentrations of SO 2 , CO 2 H 2 S, H 2 and H 2 O in real-time using both electrochemical and spectroscopic sensors. We observed extreme chemical fractionation between closely-spaced volcanic vents displaying contrasting explosive behaviour. From these data, we explore the depth and dynamics of gas exsolution in the shallow magmatic system using thermodynamic solubility models and attempt to constrain the overall volatile budget of the carbon-rich alkaline magmas characteristic of the Canary Islands, alongside petrological observations from erupted lavas.

Caption: Preparing the drone and aerial MultiGAS system to acquire in-situ chemical measurements within the volcanic gas plume. Featuring Emma Liu (left) and Kieran Wood (right).

As well as emitted gases, there was concern over the air quality impacts of volcanic trace elements that are emitted as fine aerosol particulates. During the effusive eruption of Kilauea in 2018, I was involved in two studies that demonstrated how volatile metallic elements classified as environmental pollutants (e.g., Cu, Pb, Zn) are released from magmas in large amounts during degassing and can be transported up to hundreds of kilometres from the eruptive source within volcanic plumes (Ilyinskaya et al., 2021; Mason et al., 2021). I was interested in the “fingerprint” of these volcanic metals being emitted from both the high-temperature eruptive vents of Cumbre Vieja and also the ocean entry site, where lava flows were entering the ocean and interacting explosively to produce a plume rich in water and chlorine. I sampled these aerosols using filter packs and cascade impactors, which collect bulk and size-segregated particulates, respectively. I then digested the filter samples in the new metal-free laboratory at UCL and analysis of their trace element compositions is currently in progress. The eruption lasted for 84 days, making it the longest eruption on La Palma in historical times. At the time of writing, activity has currently paused and only time will tell whether the eruption is truly over or whether magma is continuing to accumulate in the subsurface. For the communities living on La Palma, this end to activity brings the first hope that they may soon begin to rebuild and marks the beginning of a new stage of recovery. For the volcanological community, we have much to learn from this eruption. The breadth of monitoring data collected by so many international teams, all coordinated expertly by INVOLCAN, will provide many opportunities to improve our understanding of magmatic and eruptive processes for years to come. I wish to thank my colleagues and friends who collaborated with me in this response effort and to INVOLCAN for their warm welcome and unbounded support.

Mason, E., Wieser, P.E., Liu, E.J., Edmonds, M., Ilyinskaya, E., Whitty, R.C., Mather, T.A., Elias, T., Nadeau, P.A., Wilkes, T.C. and McGonigle, A.J., 2021. Volatile metal emissions from volcanic degassing and lava–seawater interactions at Kīlauea Volcano, Hawai’i. Communications Earth & Environment , 2 (1), pp.1-16.

Ilyinskaya, E., Mason, E., Wieser, P.E., Holland, L., Liu, E.J., Mather, T.A., Edmonds, M., Whitty, R.C., Elias, T., Nadeau, P.A. and Schneider, D., 2021. Rapid metal pollutant deposition from the volcanic plume of Kīlauea, Hawai’i. Communications Earth & Environment , 2 (1), pp.1-15.

- Dr Emma Liu’s academic profile

2021 Autumn Newsletter

Funnelback feed: https://cms-feed.ucl.ac.uk/s/search.json?collection=drupal-mathematical-... Double click the feed URL above to edit

La Palma Eruption 2021

Date: Sept. 19, 2021 Type: Volcanoes Region : Africa , Canary Islands Info & Resources:

- View maps & data products for the La Palma eruption on the NASA Disasters Mapping Portal

- NASA Disasters program resources for volcanoes

- Latest updates from the Instituto Geologico y Minero de Espana (IGME)

- Latest updates from the Smithsonian Global Volcanism Program

- Latest updates from the Instituto Volcanológico de Canarias (INVOLCAN)

- Educational story map of La Palma data products & visualizations, developed by Esri

UPDATE Oct. 13, 2021

View fullscreen on the NASA Disasters Mapping Portal

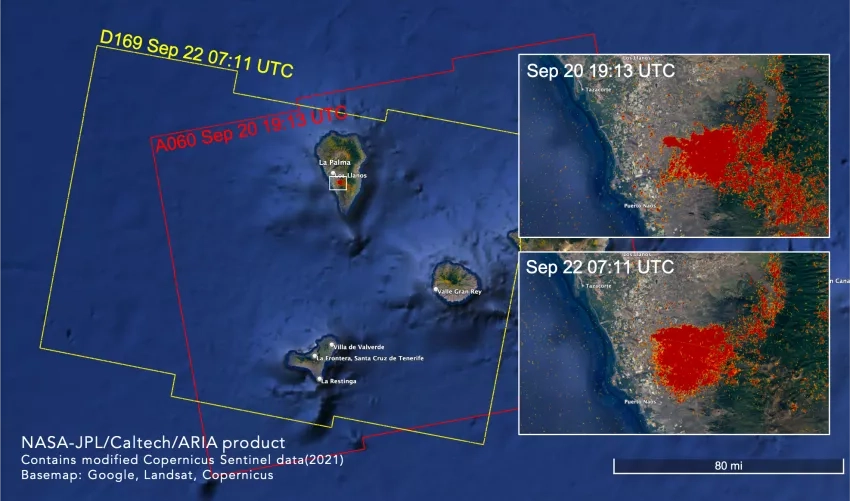

Researchers working with the NASA ROSES A.37 project “ Day-Night Monitoring of Volcanic SO2 and Ash for Aviation Avoidance at Northern Polar Latitudes ” developed this animation of sulfur dioxide (SO2) clouds from the La Palma eruption using satellite data from NASA / NOAA Suomi-NPP and NOAA-20 Ozone Mapping and Profiler Suite (OMPS) spectrometers. Both satellites fly similar near-polar orbits, but are about 50 minutes apart. NOAA-20 OMPS measures with higher ground resolution. Using two satellites allows researchers to make more frequent, precise observations to identify hazardous densities of volcanic gases and aerosols.

The above animation shows SO2 column density in Dobson Units (1 DU = 2.69 x 1016 SO2 molecules /cm2) from Sept. 19 – 30, 2021. S02 is used to indicate the presence of volcanic gases and also as a proxy for volcanic aerosols (sulfuric acid or vog and ash), which can negatively affect air quality for people living in the region, as well as potentially damage aircraft flying through the volcanic clouds. Credits: NASA

Update Oct. 4, 2021

On Sept. 19, 2021, the Cumbre Vieja volcano on the island of La Palma in the Canary Islands started erupting after remaining dormant for 50 years. Since the initial eruption, the volcano has seen several Strombolian explosions , significant emissions of ash and gas, and multiple vents spewing molten lava down the mountain and into surrounding regions. According to the latest media reports over 800 buildings have been destroyed and about 6,000 people evacuated from the area.

The NASA Earth Applied Sciences Disasters program area has activated efforts to monitor the eruption and provide Earth-observing data and analysis in support of risk reduction and recovery for the eruption. The program is in contact with colleagues from the Instituto Geologico y Minero de Espana ( IGME ) and the Institut de Physique du Globe de Paris ( IPGP ) to share knowledge and data for situational awareness.

These efforts are being supported by the NASA ROSES A.37 research projects “ Day-Night Monitoring of Volcanic SO2 and Ash for Aviation Avoidance at Northern Polar Latitudes ” and “ Global Rapid Damage Mapping System with Spaceborne SAR Data .”

Related Impact

Connect with the Disasters Program

With help from NASA’s Earth-observing satellites, our community is making a difference on our home planet. Find out how by staying up-to-date on their latest projects and discoveries.

Stay Connected

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

La Palma's volcanic eruption is officially over, but its devastating toll lingers

The Associated Press

A fissure is seen next to a house covered with ash on the Canary island of La Palma on Dec. 1. Authorities on the Spanish island are declaring a volcanic eruption that has caused widespread damage but no casualties officially finished. Emilio Morenatti/AP hide caption

A fissure is seen next to a house covered with ash on the Canary island of La Palma on Dec. 1. Authorities on the Spanish island are declaring a volcanic eruption that has caused widespread damage but no casualties officially finished.

MADRID — Authorities on one of Spain's Canary Islands declared a volcanic eruption that started in September officially finished Saturday following 10 days of no lava flows, seismic activity or significant sulfur dioxide emissions.

But the emergency in La Palma, the most northwest island in the Atlantic Ocean archipelago, is not over due to the widespread damage the eruption caused, the director of the Canaries' volcanic emergency committee said in announcing the much-anticipated milestone.

As a sea of lava destroys livelihoods on La Palma, it also offers a lifeline

"It's not joy or satisfaction - how we can define what we feel? It's an emotional relief. And hope," Pevolca director Julio Pérez said. "Because now, we can apply ourselves and focus completely on the reconstruction work."

Spanish army soldiers stand on a hill as lava flows on La Palma on Nov. 29. Emilio Morenatti/AP hide caption

Spanish army soldiers stand on a hill as lava flows on La Palma on Nov. 29.

Fiery molten rock flowing down toward the sea destroyed around 3,000 buildings, entombed banana plantations and vineyards, ruined irrigation systems and cut off roads. But no injuries or deaths were directly linked to the eruption.

A mysterious 'A Team' just rescued dogs from a volcano's lava zone in La Palma

Pérez, who is also the region's minister of public administration, justice and security, said the archipelago's government valued the loss of buildings and infrastructure at more than 900 million euros ($1 billion).

A house is covered by ash from a volcano on La Palma on Oct. 30. Emilio Morenatti/AP hide caption

A house is covered by ash from a volcano on La Palma on Oct. 30.

Volcanologists said they needed to certify that three key variables - gas, lava and tremors - had subsided in the Cumbre Vieja ridge for 10 days in order to declare the volcano's apparent exhaustion. Since the eruption started on Sept. 19, previous periods of reduced activity were followed by reignitions.

Spain's prime minister says La Palma will be rebuilt as lava flow continues

On the eve of Dec. 14, the volcano fell silent after flaring for 85 days and 8 hours, making it La Palma's longest eruption on record.

Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez called the eruption's end "the best Christmas present."

Lava flows on La Palma on Nov. 29. Emilio Morenatti/AP hide caption

Lava flows on La Palma on Nov. 29.

"We will continue working together, all institutions, to relaunch the marvelous island of La Palma and repair the damage," he tweeted.

Farming and tourism are the main industries on the Canary Islands, a popular destination for many European vacationers due to their mild climate.

- Canary Islands

- Israel-Gaza War

- War in Ukraine

- US Election

- US & Canada

- UK Politics

- N. Ireland Politics

- Scotland Politics

- Wales Politics

- Latin America

- Middle East

- In Pictures

- BBC InDepth

- Executive Lounge

- Technology of Business

- Women at the Helm

- Future of Business

- Science & Health

- Artificial Intelligence

- AI v the Mind

- Film & TV

- Art & Design

- Entertainment News

- Destinations

- Australia and Pacific

- Caribbean & Bermuda

- Central America

- North America

- South America

- World’s Table

- Culture & Experiences

- The SpeciaList

- Natural Wonders

- Weather & Science

- Climate Solutions

- Sustainable Business

- Green Living

Spain's La Palma volcano eruption declared over after three months

A volcano eruption on the Spanish island of La Palma has officially been declared over, after three months of spewing ash and hot molten rock.

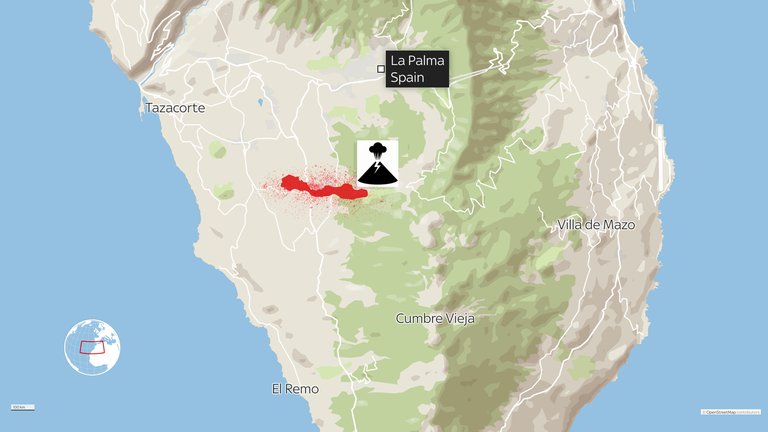

Since erupting on 19 September, the Cumbre Vieja volcano destroyed more than 3,000 properties and hundreds of acres of farmland on the Canary Island.

More than 7,000 people were forced to leave their homes as lava closed in.

But after 10 days of calmer activity, authorities decided the volcano was not going to flare up again.

"What I want to say today can be said with just four words: The eruption is over," said Canary Islands regional security chief Julio Perez.

There had been no earth tremors since 13 December - the longest period without any activity since the volcano began.

But Mr Perez said experts wanted to be sure the eruption had stopped before declaring it was over on Christmas Day.

No injuries or deaths have been linked to the eruption on the island, where about 80,000 people live.

But more than 1,300 homes have been destroyed, as well as churches, schools and swathes of banana plantations.

Molten rock leaked into the ocean which increased the size of the island, boiled sea water and released the toxic gas sulphur dioxide.

The gas forced many on the island to stay locked down in their homes.

- La Palma volcano: Visual guide to what happened

- 'Miracle house' escapes Canary Islands lava

- La Palma volcano lava engulfs homes and swimming pools

The eruption also disrupted the late stages of the summer tourist season as many flights were cancelled and resorts were closed.

It was the first eruption on La Palma since 1971 and the longest-ever recorded on the island.

Spain's Prime Minister Pedro Sanchez described the news as "the best Christmas present".

He tweeted: "We will continue working together, all the institutions, to relaunch the wonderful island of La Palma and repair the damage caused."

The Spanish government has promised €225m euros ($255m; £192m) to help people living on the island.

Volcano survivors shaken but determined to rebuild

Lava engulfs house that survived la palma eruption.

- Current Eruptions

- Smithsonian / USGS Weekly Volcanic Activity Report

- Bulletin of the Global Volcanism Network

- Weekly Report 20th Anniversary

- Holocene Volcano List

- Pleistocene Volcano List

- Country Volcano Lists

- Volcano Search

- Eruption Search

- Webservices

- Database Information

- Image Collections

- Video Collections

- Theme Collections

- Keyword Collections

- Student Art Gallery 2024

- St. Helens 40th Anniversary

- Frequent Questions

- Information Sources

- Google Earth Placemarks

- This Dynamic Planet

- Eruptions, Earthquakes & Emissions Application

- Volcano Numbers

- Volcano Naming

- How to Cite

- Terms of Use

- Canary Volcanic Province

- Composite | Stratovolcano(es)

- Volcanic Province

- Landform | Volc Type

- Last Known Eruption

- 28.57°N

- 17.83°W

- 2,426 m 7,959 ft

- Summit Elevation

- Volcano Number

- Latest Activity Reports

- Weekly Reports

- Bulletin Reports

- Synonyms & Subfeatures

- General Information

Eruptive History

Deformation history, emission history, photo gallery.

- Map Holdings

- Sample Collection

External Sites

Most recent weekly report: 15 december-21 december 2021 cite this report.

Observations at La Palma on 15 December showed no lava flowing from vents at the W base of the main cone, from tubes, or at the lava delta in the Las Hoyas area. During 15-20 December tremor levels were at background levels and seismicity was very low at all depths. Sporadic gas emissions rose from the vents and from cooling lava flows. Small collapses from the walls of the main and secondary cone craters were visible through the week. Sulfur dioxide levels varied between extremely low and medium values (less than 5 to 999 tons per day) consistent with a cooling and degassing lava flow field. Even though air quality levels had improved overall, a few measurements of diffuse carbon dioxide emissions showed levels around 9 times average background. Authorities warned the public to exercise caution in areas surrounding the flow field due to volcanic gases in the area and noted that lava flows, although cooling, remained at high temperatures.

Sources: Instituto Volcanológico de Canarias (INVOLCAN) , Gobierno de Canaries , Instituto Geográfico Nacional (IGN)

Most Recent Bulletin Report: February 2022 (BGVN 47:02) Cite this Report

Phreatomagmatic and Strombolian activity, lava effusion, and ash plumes through mid-December 2021

La Palma is a 47-km-long island at the northwestern end of the Canary Islands. It is composed of two large volcanic centers, with the younger Cumbre Vieja to the south dating back 125,000 years. Multiple eruptions during the last 7,000 years have produced mild explosive activity and lava flows which have damaged populated areas and reached the sea in 1585, 1646, 1712, 1949, and 1971. A new eruption from the SW flank began on 19 September 2021, roughly 20 km NW of the site of the 1971 eruption. Two fissures opened and multiple vents produced lava fountains, flows, and ash plumes; the flows traveled over 5 km to the W toward the coastline, eventually extending further into the ocean, damaging buildings and crops (BGVN 46:10). Information in this report describing lava fountains, flows, and ash plumes through the end of the eruption comes from Spain’s Instituto Geographico Nacional (IGN), the Instituto Volcanologico de Canarias (INVOLCAN), the Steering Committee of the Special Plan for Civil Protection and Attention to Emergencies due to Volcanic Risk (PEVOLCA), maps from Copernicus EMS, satellite data, and news and social media reports covering October through December 2021.

Summary of activity during October-December 2021. Strong eruptive activity that began on 19 September continued throughout most of this reporting period. During October, more than 3,000 earthquakes were detected in the southern part of the island and ash plumes rose as high as 5.5 km altitude, according to the Toulouse VAAC. Lava flows emerged from two new vents and moved W toward the coastline, affecting 3,063 buildings, of which 2,896 were destroyed. (figure 31). The lava flow field continued to expand through the eruption (table 2). There were a total of 11 flows numbered during this reporting period. Flow 2, located between the main flow (Flow 1), had reached the sea on 21 September. Lava, including bombs, were ejected as far as 800 m from the vent. Lava fountains rose hundreds of meters high and collapses of the crater walls were common. Similar activity was reported in November, with frequent earthquakes, ash plumes that rose to 4.6 km altitude, ejecta, and multiple lava effusions, some of which reached the coastline and formed a lava delta. Several thousand people were evacuated. During December, the number of earthquakes detected, and ash plumes was notably lower. An ash plume on 13 December rose as high as 7.5 km altitude, but overall, they were lower compared to the previous months. Strong lava effusion persisted during the first half of the month, some of which continued to feed the lava deltas on the coast. By mid-December, activity had mostly subsided, with only some incandescence, weak lava flows, and low gas-and-ash plumes. Sulfur dioxide emissions were consistently detected until mid-December.

| Figure 31. Simplified location map showing the lava flows generated from the La Palma eruption taken from drone data on 15 December 2021. The black dot represents the vent, and the orange area is the lava coverage that moved generally W. The names of the affected nearby towns are also included. Courtesy of Dirección General de Tráfico. |

Table 2. Summary of the growth of the lava flow field at La Palma between October and December 2021, listing the width of the field (m) and the covered area (km 2 ). Area values were rounded up to the nearest tenth. Data courtesy of PEVOLCA.

| Date | Width (m) | Area (km ) |

| 04 Oct 2021 | 1,250 | 4.1 |

| 08 Oct 2021 | 1,250 | 4.7 |

| 10 Oct 2021 | 1,520 | 5.3 |

| 11 Oct 2021 | 1,520 | 5.9 |

| 12 Oct 2021 | -- | 6.1 |

| 13 Oct 2021 | 1,770 | 6.4 |

| 16 Oct 2021 | 2,350 | 7.2 |

| 17 Oct 2021 | 2,350 | 7.4 |

| 19 Oct 2021 | 2,900 | 7.8 |

| 20 Oct 2021 | 2,900 | 8.0 |

| 22 Oct 2021 | 2,900 | 8.5 |

| 26 Oct 2021 | -- | 8.8 |

| 03 Nov 2021 | 3,100 | 9.8 |

| 09 Nov 2021 | 3,100 | 9.9 |

| 11 Nov 2021 | 3,100 | 10.1 |

| 13 Nov 2021 | 3,100 | 10.2 |

| 16 Nov 2021 | 3,200 | 10.3 |

| 23 Nov 2021 | 3,300 | 10.7 |

| 24 Nov 2021 | 3,300 | 10.9 |

| 25 Nov 2021 | 3,350 | 11.0 |

| 27 Nov 2021 | -- | 11.5 |

| 30 Nov 2021 | 3,350 | 11.3 |

| 02 Dec 2021 | 3,350 | 11.4 |

| 05 Dec 2021 | 3,350 | 11.6 |

| 07 Dec 2021 | 3,350 | 11.8 |

| 14 Dec 2021 | 3,350 | 12.0 |

| 25 Dec 2021 | -- | 12.2 |

Activity during October 2021. Frequent earthquakes were detected during October (a total of 3,416 on the island of La Palma), 635 of which were felt by the nearby communities; most were located 10-15 km deep in the SE area of the island where the swarm had initiated in early September, though some were recorded at depths greater than 30 km (figure 32). The strongest events, magnitude 5.0, occurred on 30 and 31 October at depths of 35 and 38 km, respectively.

| Figure 32. Map of seismic events at La Palma showing the location of earthquakes on the SE part of the island during 1-31 October 2021, which remained in the same location as those detected on 11 September 2021. The depths of these events range up to 40 km. The color bar on the right represents the dates of the seismic events beginning on 1 October. Courtesy of IGN (Actualización de la información sobre la actividad volcánica en el sur de la isla de La Palma). |

The Toulouse VAAC issued 320 volcanic ash advisories (VAA) for aviation during the reporting period, based on data from satellite imagery and webcams. During October, 132 VAAs described ongoing ash emissions that reached 1.8-5.5 km altitude and drifted up to 185 km in different directions. Some ashfall deposits were reported near the volcano.

By 1 October, roughly 80 million cubic meters of lava had been erupted. Two vents opened about 600 m NW from the main cone on 1 October, forming small cones within two days. Lava from these vents traveled W, then connected with the main flow field downslope. Explosions ejected centimeter-sized material as far as 3.3 km from the cone, and ash and lapilli deposits were reported in areas downwind. The lava flow had extended 540 m beyond the original coastline. Based on satellite images from Copernicus, more than 1,000 buildings had been destroyed in El Pason, Los Llanos de Aridane, and Tazacorte. Ash plumes rose to 3-5 km altitude and drifted S on 2 October.

By 3 October the width of the lava flow field was a maximum of 1,250 m and lava tubes were identified in satellite images. The lava flow had developed four lobes that were fed by multiple lava flows and had an estimated area of 4.1 km 2 . In the afternoon, the frequency and intensity of the explosions ejected bombs as far as 800 m. Lava fountains rose hundreds of meters high. During 1900-1945 one of the new cones collapsed and spilled into the inner lava lake; lava flows traveled downslope carrying blocks from the destroyed parts of the cone. By 5 October the volume of erupted lava was estimated to be 35 million cubic meters, according to INVOLCAN.

On 6 October a breakout lava flow from the W end of the main flow field traveled S between Los Guirres and El Charcó, destroying crops and buildings (figure 33). On 8 October a new vent had formed on the main cone as ash plumes rose as high as 3.5 km altitude and lightning was occasionally visible; ash deposits at the La Palma and Tenerife North (on Tenerife Island) airports caused a temporary shutdown. The N part of the cone collapsed on 9 October, generating a wide, multi-lobed flow carrying larger blocks NW over older flows (figure 34), based on a news article from Europe Press. The flow quickly advanced to the W along the N margins of the flow field, causing more damage in Todoque and an industrial area.