- Utility Menu

- Internal Resources

- EDIB Committee

Archaeology

The principal objectives of the graduate program in archaeology are to provide:

- Informed, critical examinations of core issues in archaeology

- Comprehensive training in principal methods and theories of anthropologically oriented archaeology

- Direction and support for Ph.D. candidates preparing for research and teaching positions in a wide variety of domains of archaeological practice.

In addition to a primary area of specialization, all students are expected to acquire a basic understanding of archaeology around the world as well as general knowledge of those aspects of ethnography, and biological anthropology that have particular relevance to their area(s) of interest in archaeology.

In certain cases, joint programs of study in archaeology and either biological anthropology or social anthropology can be arranged. The expectation is that the student will be able to complete the program in six years.

Each student will have faculty advisors whose research interests overlap with those of the student. For the first four semesters student’s progress will be overseen by an Advisory Committee, normally consisting of three archaeology faculty members. After the fourth semester, a dissertation committee will be formed based on the student's domain(s) of specialization.

The progress of each student will be assessed annually by the archaeology program faculty, and this appraisal will be communicated to the candidate. An overall B+ average is expected of the student. Ordinarily no student whose record contains an Incomplete grade will be allowed to register for the third term (semester) following receipt of the Incomplete.

- Admissions Information

- Coursework - Archaeology

- Languages - Archaeology

- Fieldwork - Archaeology

- Teaching - Archaeology

- Advisory Meetings - Archaeology

- General Examination & Qualifying Paper - Archaeology

- Dissertation Prospectus - Archaeology

- Dissertation Committee & Defense - Archaeology

- Master of Arts - Archaeology

- Social Anthropology

- MA Medical Anthropology

- Secondary Fields

- Fellowships

- Teaching Fellows

- Program Contacts

- PhD Recipients

- Utility Menu

GA4 Tracking code

- Connect with Us

- PhD Program in Anthropology and Middle Eastern Studies

Admissions to the PhD in Anthropology and MES has been paused and will not be accepting applications for fall 2024.

The joint program in Anthropology and Middle Eastern Studies is designed for students interested in enriching their program of study for the PhD in Anthropology with firsthand knowledge about the Middle East based on literacy in its languages and an understanding of its cultural traditions. As a student in an interdisciplinary program you are a full member of the Department of Anthropology cohort, but also have an intellectual home at CMES and access to CMES faculty, facilities, and resources.

Students in the joint PhD Program in Anthropology and Middle Eastern Studies fulfill all the requirements for the PhD in Social Anthropology in addition to the language and area studies requirements established by the Committee on Middle Eastern Studies.

Language Requirements

Each student must demonstrate a reading knowledge of one of the following European languages: German, French, Italian, or Russian. This requirement may be fulfilled either by a departmental examination or by satisfactory completion of two years of language study. The student must also demonstrate a thorough knowledge of a modern Middle Eastern language: Arabic, Hebrew, Persian, or Turkish. Depending on the student’s specialization, another Middle Eastern or Islamic language (e.g., Kurdish, Urdu) may be substituted with the approval of the Committee on Joint PhD Programs. The expectation is that the student learn the languages necessary to teach and work in his or her chosen field.

Program of Study in Anthropology and MES

The graduate program in social anthropology and Middle Eastern Studies requires a minimum of sixteen half-courses, three of which are in Middle Eastern history, economics, religion, or political science, and twelve of which are in anthropology. The twelve required anthropology half-courses include the proseminar “History and Theory of Social Anthropology” (2650a and b); a half-course on the ethnography of one’s area of specialization is recommended but not required. A half-course in archaeology is recommended but not required. First-year students must attain at least a B+ in each half of the proseminar.

A list of current Middle East–related courses is available on this site at the beginning of each semester ; the Anthropology Department courses are available at my.harvard.edu .

Social anthropology PhD candidates are required to take written and oral examinations toward the end of their third term of study. Candidates must pass these examinations before they may continue their PhD work. More details are available in the Department of Anthropology’s Program Guidelines for students .

Dissertation

The dissertation prospectus must be read and approved by a committee of three faculty members no later than the end of the third year. The dissertation will normally be based on fieldwork conducted in the Middle East, or in other areas of the world with close cultural ties to the region, and should demonstrate the student’s ability to use source material in one or more relevant Middle Eastern languages. Satisfactory progress of PhD candidates in the writing stage is determined on the basis of the writing schedule the student arranges with his or her advisor.

Timeline for Student Progress and Degree Completion

- Coursework: One to three years.

- Examinations: General exams must be passed by the end of the second year of study.

- Dissertation Prospectus: Must be approved by the end of the third year.

- Dissertation Defense and Approval: The candidate’s dissertation committee decides when the dissertation is ready for defense. The doctorate is awarded when the candidate passes a defense of the dissertation.

- Graduation: The program is ideally completed in six years.

For more details on these guidelines, see the Middle Eastern Studies section of the Harvard Kenneth C. Griffin Graduate School of Arts and Sciences (Harvard Griffin GSAS) Policies site and the Department of Anthropology’s guidelines for PhD students in social anthropology . Admissions information can be found in the Applying to CMES section of this site and on the Harvard Griffin GSAS website .

- Applying to CMES

- Concurrent AB/AM Program

- PhD Program in History and Middle Eastern Studies

- PhD Program in History of Art and Architecture and Middle Eastern Studies

- Recent PhD Dissertations

- Funding for PhD Students

- Middle East-related Courses

- Harvard Griffin GSAS Policies

Anthropology Degree Requirements

The Master of Liberal Arts, Anthropology degree field is offered online with 1 on-campus requirement at Harvard University. Weekend on-campus courses are available.

Getting Started

Explore admissions & degree requirements.

- Course curriculum and the on-campus experience

- Admissions: eligibility and earning your way in

- Completing your degree

Begin Your Admissions Path This Upcoming Spring

Enroll in your first admission course. Registration is open November 4, 2024–January 23, 2025.

Learn how to register →

Required Course Curriculum

Online core and elective courses

On-campus Engaging in Scholarly Conversation course

Capstone or thesis

12 Graduate Courses (48 Credits)

Many of our anthropology offerings focus on identity and social justice, making it an ideal option for professionals in the fields of education, community development, public service, public health, NGOs, as well as management and diversity, inclusion and belonging.

As part of the program curriculum, you pursue either a thesis or capstone track. You can further customize the program by choosing the anthropology and elective courses that meet your learning goals.

The primarily synchronous online format ensures real-time engagement with faculty and peers.

Required Core & Elective Courses View More

- SSCI 100A Proseminar: Introduction to Graduate Studies in Anthropology and Psychology

- 4 anthropology courses

- 1 anthropology seminar

- This 4-credit requirement is fulfilled by completing 2 two-credit Active Learning Weekends or 1 three-week summer course.

- EXPO 42b Writing in the Social Sciences is an elective option.

Browse Courses →

Thesis Track View More

The thesis is a 9-month independent research project where you work one-on-one in a tutorial setting with a thesis director.

You enroll in the following additional courses for the thesis track:

- ANTH 497 Crafting the Thesis Proposal in Anthropology Tutorial

- ANTH 499AB ALM Thesis in Anthropology (8 credits)

Recent Thesis Topics:

- Maya Vase Rollout Photography’s Past, Present, and Potential in a Cross-Discipline Digital Future: A Proof-of-Concept Study

- When Witches Mourn the Dead: Grieving Rituals of Contemporary Witchcraft in New England

- From Memes to Marx: Social Media as the New Frontier of Ruling Class Dominance

Capstone Track View More

The capstone track focuses on a capstone project and includes the following additional courses. You choose between two precapstone and capstone topic areas.

- 1 anthropology elective

- SSCI 597B Identity Precapstone: Theory and Research

- SSCI 599B Identity Capstone: Bridging Research and Practice

- GOVT 597A Precapstone: Strategies to Advance Social Change

- GOVT 599A Social Justice Capstone: Equity and the Struggle for Justice

Capstone experience. First, in the precapstone, you gain foundational preparation through critically analyzing the scholarly literature. Then, in the capstone, you execute a semester-long research project with guidance and support from your instructor and fellow candidates.

Capstone sequencing. You enroll in the precapstone and capstone courses in the same topic, in back-to-back semesters (fall/spring), and in your final academic year. The capstone must be taken alone as your sole remaining degree requirement. Capstone topics are subject to change annually.

Recent Capstone Topics:

- Addressing Sexism in Video Game Culture: Empowering Female Players through a Mobile Application for Inclusivity, Visibility, and Support

- Bermuda Wrecks Conservation Through Public Archaeology, Technology and Ease of Access: The “Bermuda Wrecks” Smartphone Application

- Advocating for Healthy Habits in the Digital Age of Education

Optional Graduate Certificate View More

You can choose to concentrate your degree studies to earn a Social Justice Graduate Certificate along the way.

Harvard Instructor Requirement View More

For either the thesis or capstone track, 8 courses (32 credits) of the above courses need to be taught by instructors with the Harvard-instructor designation. The thesis courses are taught by a Harvard instructor.

On Campus Experience

Choose between the accelerated or standard on-campus experience.

Learn and network in-person with your classmates.

Nearly all courses can be taken online, but the degree requires an in-person experience here at Harvard University where you enroll in Engaging in Scholarly Conversation (ESC).

Join your fellow degree candidates for this interactive course that highlights the importance of true graduate-level analysis by training you in the skills of critically engaging the scholarly literature in your field of study.

Choose between two on-campus experience options:

- Accelerated on-campus option: ESC is offered in two, 2-credit Active Learning Weekends. We strongly advise you complete the two weekends in the same academic year with same instructor (part one in fall and part two in spring).

- Standard on-campus option: ESC is offered in one 3-week Harvard Summer School session. This option is ideal for those who want a more traditional on-campus experience. HSS offers, for an additional fee, housing, meal plans, and a prolonged on-campus experience here at Harvard University. Learn more about campus life at Harvard .

You register for ESC after completing the proseminar with a grade of B or higher and prior to either the Crafting the Thesis Proposal tutorial or the precapstone to support your final research project. Ordinarily, students wait until they are officially admitted before enrolling in this requirement, as it does not count as one of the three, 4-credit courses required for admission.

You have two attempts to earn the required grade of B- or higher in ESC. A withdrawal grade (WD) counts as an attempt.

Whether working on a paper at one of the libraries or shopping at the Harvard Coop, I always felt like I belonged.

On attending Engaging in Scholarly Conversation in the active learning weekend format.

International Students Who Need a Visa View More

To meet the on-campus requirement, you choose the Standard on-campus option and study with us in the summer. You can easily request an I-20 for the F-1 student visa for Harvard Summer School’s 3-week session. For more details, see International Student Study Options for important visa information .

In-Person Co-Curricular Events View More

Come to Cambridge for Convocation (fall) to celebrate your hard-earned admission, Harvard career fairs offered throughout the year, HES alumni networking events (here at Harvard and around the world), and, of course, Harvard University Commencement (May).

Confirm your initial eligibility with a 4-year bachelor’s degree or its foreign equivalent.

Take three courses in our unique “earn your way in” admissions process that count toward your degree.

In the semester of your third course, submit the official application for admission to the program.

Below are our initial eligibility requirements and an overview of our unique admissions process to help get you started. Visit the Degree Program Admissions page for more details.

Initial Eligibility View More

- Prior to enrolling in any degree-applicable courses, you must possess a 4-year regionally accredited US bachelor’s degree or its foreign equivalent. Foreign bachelor’s degrees must be evaluated for equivalency.

- If English is your second language, you’ll need to prove English proficiency before registering for a course. We have multiple proficiency options .

Earning Your Way In — Courses for Admission View More

To begin the admission process, you simply register — no application required — for the following three, 4-credit, graduate-level degree courses (available online).

These prerequisite courses are investments in your studies and help ensure success in the program. They count toward your degree once you’re admitted; they are not additional courses.

- Before registering, you’ll need to pass our online test of critical reading and writing skills or earn a B or higher in EXPO 42b Writing in the Social Sciences.

- You have 2 attempts to earn the minimum grade of B in the proseminar (a withdrawal grade counts as an attempt). The proseminar cannot be more than 2 years old at the time of application.

- 1 Anthropology course

- 1 Anthropology course or elective (e.g., EXPO 42b)

While the three courses don’t need to be taken in a particular order or in the same semester, we highly recommend that you start with the proseminar (or the prerequisite EXPO 42b). All three courses must be completed with a grade of B or higher, without letting your overall Harvard cumulative GPA dip below 3.0.

Applying to the Degree Program View More

During the semester of your third degree course, submit the official application to the program.

Don’t delay! You must prioritize the three degree courses for admission and apply before completing subsequent courses. By doing so, you’ll:

- Avoid the loss of credit due to expired course work or changes to admission and degree requirements.

- Ensure your enrollment in critical and timely degree-candidate-only courses.

- Avoid the delayed application fee.

- Gain access to exclusive benefits.

Eligible students who submit a complete and timely application will have 9 more courses after admission to earn the degree. Applicants can register for courses in the upcoming semester before they receive their grades and while they await their admission decision.

Prospective ALM students can expect acceptance into the program by meeting all the eligibility and academic requirements detailed on this page, submitting a complete application, and having no academic standing or conduct concerns.

The Office of Predegree Advising & Admissions makes all final determinations about program eligibility.

Search and Register for Courses

The Division of Continuing Education (DCE) offers degree courses all year round to accelerate degree completion.

- You can study in fall, January, and spring terms through Harvard Extension School (HES) and during the summer through Harvard Summer School (HSS).

- You can enroll full or part time. After qualifying for admission, many of our degree candidates study part time, taking 2 courses per semester (fall/spring) and 1 in the January and summer sessions.

- Most fall and spring courses meet once a week for two hours, while January and summer courses meet more frequently in a condensed format.

Completing Your Degree

Maintain a cumulative GPA of 3.0 or higher.

Complete your courses in five years.

Earn your Harvard degree and enjoy Harvard Alumni Association benefits upon graduation.

Required GPA, Withdrawal Grades, and Repeat Courses View More

GPA. You need to earn a B or higher in each of the three degree courses required for admission and a B– or higher in each of the subsequent courses. In addition, your cumulative GPA cannot dip below 3.0.

Withdrawal Grades. You are allowed to receive two withdrawal (WD) grades without them affecting your GPA. Any additional WD grades count as zero in your cumulative GPA. See Academic Standing .

Repeat Courses. We advise you to review the ALM program’s strict policies about repeating courses . Generally speaking, you may not repeat a course to improve your GPA or to fulfill a degree requirement (if the minimum grade was not initially achieved). Nor can you repeat a course for graduate credit that you’ve previously completed at Harvard Extension School or Harvard Summer School at the undergraduate level.

Courses Expire: Finish Your Coursework in Under Five Years View More

Courses over five years old at the point of admission will not count toward the degree. As stated above, the proseminar cannot be more than two years old at the time of application.

Further, you have five years to complete your degree requirements. The five-year timeline begins at the end of the term in which you complete any three degree-applicable courses, regardless of whether or not you have been admitted to a degree program.

Potential degree candidates must plan accordingly and submit their applications to comply with the five-year course expiration policy or they risk losing degree credit for completed course work. Additionally, admission eligibility will be jeopardized if, at the point of application to the program, the five-year degree completion policy cannot be satisfied (i.e., too many courses to complete in the time remaining).

Graduate with Your Harvard Degree View More

When you have fulfilled all degree requirements, you will earn your Harvard University degree: Master of Liberal Arts (ALM) in Extension Studies, Field: Anthropology. Degrees are awarded in November, February, and May, with the annual Harvard Commencement ceremony in May.

Degree Candidate Exclusive Benefits View More

When you become an officially admitted degree candidate, you have access to a rich variety of exclusive benefits to support your academic journey. To learn more, visit degree candidate academic opportunities and privileges .

Harvard Division of Continuing Education

The Division of Continuing Education (DCE) at Harvard University is dedicated to bringing rigorous academics and innovative teaching capabilities to those seeking to improve their lives through education. We make Harvard education accessible to lifelong learners from high school to retirement.

Get the Reddit app

A subreddit dedicated to PhDs.

Is a PhD from Harvard worth it?

I’m currently an undergrad in the Us looking into completing a PhD. I am considering getting a PhD at Harvard. However, I’m wondering if Harvard holds the same pedigree when it comes to grad schools.

By continuing, you agree to our User Agreement and acknowledge that you understand the Privacy Policy .

Enter the 6-digit code from your authenticator app

You’ve set up two-factor authentication for this account.

Enter a 6-digit backup code

Create your username and password.

Reddit is anonymous, so your username is what you’ll go by here. Choose wisely—because once you get a name, you can’t change it.

Reset your password

Enter your email address or username and we’ll send you a link to reset your password

Check your inbox

An email with a link to reset your password was sent to the email address associated with your account

Choose a Reddit account to continue

Insecurity and Democracy in Haiti

Erica Caple James, PhD '03, on the roots of the Caribbean nation's current unrest

Share this page

Erica Caple James, PhD ’03, is a medical and psychiatric anthropologist whose first book, democratic insecurities: violence, trauma, and intervention in Haiti, documented the psychosocial experience of Haitian torture survivors targeted during the 1991–1994 coup period, analyzing the politics of humanitarian assistance in “post-conflict” nations making the transition to democracy. Currently a professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, James outlines the roots of the country’s current unrest and says that ultimately, stability and security must come through governance that is accountable to Haiti’s people.

What does the Creole word ensekirite mean?

In a word, “insecurity” but of a particular kind. It’s very much like what the social scientist Anthony Giddens calls ontological insecurity—insecurity at the level of being from one moment to the next. Many in Haiti can’t assume a normative level of security from the built environment, social institutions, or family—none of the aspects of life that help humans develop psychologically and otherwise. Ensekirite in Haiti plays out in almost every area of life— including the physical bodies of the people there. Almost invariably, when Haitians described ensekirite and outer social space to me during my research, they also linked it to back pain, frequent headaches, and stomachaches. Their psychological experience had been somaticized: fear was ar ticulated and experienced in the body. It was almost embedded at the cellular level.

How did it start?

A native Haitian person would understand ensekirite specifically as connoting political and criminal violence between 1991 and 1994 after the coup that overthrew then-President JeanBertrand Aristide, but it began under the hereditary dictatorship of the Duvalier family that ruled Haiti from 1957 until its overthrow in 1986.

After his election in 1957, Francois Duvalier—“Papa Doc”—declared himself president for life and established a paramilitary force, the Tonton Macoute, to consolidate power. At first, it targeted more elite families that tended to be of mixed heritage. Then the use of repression spread to the general population and became indiscriminate, extending to women, children, and the elderly—populations that were formerly considered untouchable or innocent. The strategy was to control everyday life through a sort of violence that violated ethical and moral norms. Keep in mind that the government of Haiti throughout this time was viewed as a friend to the United States, which felt that its business interests benefited from having a strong authoritarian leader in control.

Ensekirite in Haiti plays out in almost every area of life, including the physical bodies of the people

The election of Jean-Bertrand Aristide as president was a moment of hope for Haiti. Then the coup you mentioned forced him to flee in 1991. In 1994, US and UN forces intervened to provide aid and restore democracy. Why weren’t these efforts successful?

The way that US aid was distributed was often governed and structured by a specific goal that was intended to benefit US business interests abroad. International development assistance was a means to create favorable economic relations, so the institutions supported didn’t necessarily have the autonomy, sovereignty, or authority of Haiti as their primary goal. Additionally, aid was funneled through so-called independent institutions—nongovernmental organizations—because it was thought that Haitian institutions of governance could not be trusted. These programs usually had a grant cycle—I call it a grant economy—in which the provision of aid was intended to meet particular deliverables. And so, whether it was a citizenship education initiative or a police-community relations program or, in rare cases, housing, the gaze of the person in charge of the funds was back to the donor and less to the people they were meant to serve. The fulfillment of the deliverable was, in part, the goal—along with the hope of renewed funding.

The second iteration of the US Agency for International Development-supported Human Rights Fund, for instance, aimed to promote human rights and democracy and also to reduce the negative psychosocial symptoms that Haitian victims of human rights abuses experienced. During my research, I found that the process of providing psychological support was often shaped by the need to make it empirically legible to the larger donor institution. The need to manage funds and to fulfill a certain set of results within a specific grant cycle or calendar put a tremendous amount of pressure on those delivering aid. But the time frame didn’t necessarily accord in any way with the path of Haitians toward greater security, lower symptomatology, greater capacity to find stable employment, etc. And, of course, this all occurred in the larger context of ensekirite.

Is there any end in sight to the extreme unrest in the country?

I think the biggest challenge is disarmament. If the gangs don’t disarm then there will be no ability to create conditions in which folks are not afraid of kidnapping or violence. There’s the possibility of integrating the gangs into civil society as political actors, but, again, are they going to remain armed? There was an effort to incorporate gang members into the national police force in the 1990s and it created divisions and conflicts that recurred for years afterward. There needs to be a Haitian-initiated plan for security and the sustainability of democracy that is supported by the population. That’s the best way to build institutions that can move beyond governance by force and build a civil society.

Curriculum Vitae Massachusetts Institute of Technology Professor of Medical Anthropology and Urban Studies, 2023-Present Associate Professor of Medical Anthropology and Urban Studies, 2017-2023 Assistant/Associate Professor of Anthropology, 2004-2017 Harvard Medical School Lecturer, Department of Global Health and Social Medicine, 2015-2017 Harvard University PhD in Social Anthropology, 2003 Harvard Divinity School MTS, 1995 Princeton University AB in Anthropology, 1992

Get the Latest Updates

Join our newsletter, subscribe to colloquy podcast, connect with us, view the entire issue, view all issues online, related news.

Who Will Win the 2024 Election?

American University Professor Allan Lichtman, PhD '73, makes his prediction based on his 13 Keys to the White House, a model that has successfully forecast 9 of the last 10 presidents.

What to Know about the Space Economy

Outer space has come a long way since the 1960s. HBS Professor Matthew Weinzierl, PhD '08, explains the current state of the space economy, highlighting the various opportunities for businesses hidden among the stars.

Curbing Cancer’s Spread

Jessalyn Ubellacker, PhD ’18, is making the lymph nodes a less hospitable environment for cancer.

Paying It Forward

The members of the 2024 Centennial Medalist cohort—like those of the past 35 years—have defined excellence in their chosen fields.

Alumni Relations

The Office of Alumni Relations encourages connections between alumni and the University, partnering with alumni leaders, students, and administrators to develop opportunities for engagement.

HUMS manages various mail centers throughout the Cambridge and Allston campuses. Please find more details about additional mail centers below.

Division of Continuing Education expand_more

The DCE Mail Center serves 51 Brattle Street and satellite DCE offices. The HUMS mail operation provides sorting, delivery, and processing of outgoing mail.

The DCE Center Mail Center can be reached at [email protected] .

Graduate School of Arts & Sciences expand_more

The GSAS Mail Center, located in the basement of Perkins Hall, serves the following dormitories of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences:

- Child Hall - 26 Everett St.

- Conant Hall - 36 Oxford St.

- Perkins Hall - 35 Oxford St.

- Richards Hall - 24 Everett St.

The address of residents receiving mail at the GSAS Mail Center should be formatted as follows:

<Full Name> <Mailbox Number><Hall> GSAS Mail Center Cambridge, MA 02138

So, for example,

John Harvard 123 Child Hall GSAS Mail Center Cambridge, MA 02138

This is the best way to address your mail. However, some carriers will require a street address, which are listed above.

The GSAS Mail Center is open Monday through Friday from 8:00 a.m. to noon, 1:00 p.m. to 5:00 p.m., and Saturday from 10:00 a.m. to 2:00 p.m.

All mail is sorted into mailboxes and residents are notified via email when a parcel is received for them. Residents may drop off mail or parcels they wish to send out via USPS, UPS, or FedEx – provided postage or prepaid labels are already attached. Due to the high turnover rate at these dormitories, the GSAS Mail Center works closely with the Harvard Student Mail Forwarding Center to help ensure that any mail for former residents is forwarded to them.

Harvard University Housing expand_more

HUMS provides limited package services to Harvard University Housing residents at the following locations:

- 10 Akron St.

- 5 Cowperthwaite St.

- 29 Garden St.

- Peabody Terrace

- Soldiers Field Park

- 1 Western Avenue

Please direct inquiries to your local building management or [email protected] .

Center for Government and International Studies expand_more

The mail center at the Center for Government and International Studies (CGIS) serves all the buildings which house the center. Our staff provides sorting, delivery, and processing of outgoing mail as well as advice to CGIS staff on USPS policies and HUMS services.

The CGIS Mail Center can be reached at (617) 495-8659 or [email protected] .

Littauer Hall expand_more

The mail center at Littauer is open from 1:00 p.m. to 2:30 p.m. Monday through Friday. HUMS sorts and delivers mail and forwards mail for staff and faculty who no longer have offices in the building.

The Littauer Mail Center can be reached at [email protected] .

Science and Engineering Complex expand_more

HUMS provides full-service loading dock and mail center management at the Science and Engineering Complex, 150 Western Avenue in Allston.

The SEC loading dock can be reached at (617) 496-0444 or [email protected] .

Smith Campus Center expand_more

The Smith Campus Center (SCC) houses many of Harvard’s Central Administration offices. The HUMS SCC mail operation provides sorting, delivery, processing of outgoing mail, courier deliveries to other parts of campus, and some specialized work specific to individual departments. The mail center at the Smith Campus Center is open Monday through Friday from 8:00 a.m. - 5:00 p.m.

The Smith Campus Center Mail Center can be reached at (617) 495-4183 or [email protected] .

Graduate School of Education expand_more

The GSE Mail Center serves the buildings and offices of the Graduate School of Education, including Gutman Library, Longfellow Hall, and Larsen Hall, as well as the various satellite offices located around Harvard Square. We receive, sort, and distribute all incoming USPS mail and parcels and deliverables arriving through private carriers such as UPS, FedEx, and DHL. We also prepare outgoing USPS mailings and ensure that outgoing items prepared by offices are received by the appropriate carriers.

As the GSE Mail Center is part of the HUMS system, the Graduate School of Education has access to various other HUMS services beyond the ones provided strictly by the GSE Mail Center. These include tracking of all incoming parcels from the time of receipt at the University through delivery, an on-call, desk-to-desk courier service, and a customer service line dedicated to HUMS constituents.

To reach us,

HUMS Customer Service (7:00 a.m. - 5:00 p.m.): Phone: (617) 496-6245 Emaill: [email protected]

GSE Mail Center: Phone: (617) 495-7751

To help us ensure quick and accurate delivery of your mail and parcels, please include all relevant address details in any items you have shipped or mailed including name, department, building, street address, and room/floor number.

House Mail Centers expand_more

HUMS maintains the mail centers for the 12 undergraduate Houses, where most undergraduate students live.

These mail centers are:

- Adams Mail Center - 26 Plympton St.

- Cabot Mail Center - 60 Linnaean St.

- Currier Mail Center - 64 Linnaean St.

- Dunster Mail Center - 945 Memorial Dr.

- Eliot Mail Center - 101 Dunster St.

- Kirkland Mail Center - 95 Dunster St.

- Leverett Mail Center - 28 DeWolfe St.

- Lowell Mail Center - 10 Holyoke Pl.

- Mather Mail Center - 10 Cowperthwaite St.

- Pforzheimer Mail Center - 56 Linnaean St.

- Quincy Mail Center - 58 Plympton St.

- Winthrop Mail Center - 32 Mill St.

Mail for residents of the House system should be addressed as follows:

<Full Name> <Mailbox Number> <House> Mail Center Cambridge, MA 02138

John Harvard 123 Adams Mail Center Cambridge, MA 02138

This is the best way to address your mail. It is not necessary to include the street address. However, some carriers will require a street address, which can be found above.

HUMS delivers all USPS and interoffice mail and parcels to these mail centers. Parcels from private carriers such as Amazon, UPS, and FedEx are delivered directly to the Houses by those carriers. All parcels are received by the House building managers’ office, which notifies residents and manages the distribution of these parcels.

Because of the high turnover rate at the Houses, all the House mail centers work closely with the Harvard Student Mail Forwarding Center to help ensure that any mail for former residents is forwarded to them, whether internal or external to the University. Additionally, if mail is mistakenly sent to a student’s first-year address, HUMS will forward it to the proper undergraduate house mailbox. To avoid delivery delays, please use the correct address.

William James Hall expand_more

The mail center at William James Hall (WJH) primarily serves the psychology, sociology, and anthropology departments. HUMS staff sort, deliver, and process outgoing mail and advise WJH staff on USPS policies and HUMS services. The WJH Mail Center is open Monday through Friday, 8:00 a.m. to noon.

The WJH Mail Center can be reached at (617) 496-3808 or [email protected] .

Transportation Alerts

MBTA Alerts City of Cambridge Alerts City of Boston Alerts Transit App

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

‘Find yourself a teacher. Win yourself a friend’

Welcome, Class of 2028. Don’t get too comfortable.

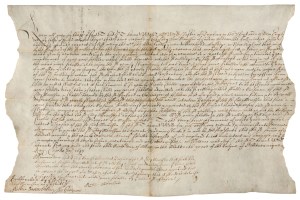

Her gift launched four centuries of Harvard financial aid

Photo illustration by Liz Zonarich/Harvard Staff

How to make the most of your first year at Harvard

Shop classes, avoid echo chambers, embrace the Red Line — and other faculty tips for new students

Harvard Staff Writer

For the more than 1,650 first-year students who moved in last week, College has already started amid excitement and occasional jitters. We asked faculty to share advice with members of the Class of 2028 on how to make the most of their first year. Here is what they had to say, in their own words.

‘Just about everyone feels overwhelmed, or lonely, or stupid, or unprepared for College at some point’

Alison frank johnson professor of history, department of history.

My first recommendation for new students is to take at least one risk academically. I don’t mean a course that seems like it’s going to be “hard” so much as something off the beaten track for Harvard first-years. There’s a lot of passed-down knowledge about what to do: take a freshman seminar, Ec 10, a big gen ed, expos, and maybe Math 1. Hundreds — literally — of your classmates will choose four out of those five options in the fall. And you might think that if everyone does it, it can’t be the wrong thing to do. Fair enough. But I would still say: Consider doing something else. Consider taking a class in a discipline that didn’t even exist in your high school but that you’re curious about. Maybe anthropology.

My second recommendation is to go to office hours, but I figure everyone says that, so I probably don’t have to elaborate.

As for as things to avoid — I guess I would say suffering in silence. It’s easy — especially at Harvard — to assume that everyone else is having a great time, that everyone else thinks classes are easy and has a ton of friends and is just having the best time ever and so if you are struggling with anything, it’s because you don’t actually belong at Harvard. But I would bet that, whether you know it or not, just about everyone feels overwhelmed, or lonely, or stupid, or unprepared for College at some point. Whatever you’re struggling with, there’s someone who wants to help you with it. There are tutors, and teaching fellows, and faculty; there are counselors, and proctors, and peer advisers, and coaches. Somewhere in that group of people is at least one person who deserves your trust and will help you. Reach out!

Dig deep when picking classes. Don’t overpack schedule.

Jie li professor of east asian languages and civilizations, department of east asian languages and civilizations.

In my last year of high school, I came across a memorable quotation from Arthur Miller at my public library. He recalled his university experience as “the testing ground for all my prejudices, my beliefs, and my ignorance.” I took this as my motto for what I wanted to get out of College as well. College is a space to meet kindred spirits, but this doesn’t necessarily mean spending time exclusively with people like you. Rather than the comfort of any echo chamber, you learn much more from people from different backgrounds. Be an empathetic listener and refrain from making quick judgments.

Don’t be afraid to take risks and venture out of your comfort zone in your choices of classes and extracurriculars. Apart from continuing what you excel at, follow your curiosity and try something new. Browse through lists of courses by department rather than only search for keywords you are already familiar with. Before classes began in my freshman year at Harvard, my roommate and I spent hours reading through a thick printed course catalog and sharing our discoveries of interesting classes and fields unavailable to us in high school. Had I only relied on algorithms to choose classes, I may not have ended up studying anthropology or film studies. Take some small classes. You will get to know your professor and classmates much better, feel more invested in the class, and thus participate more actively. Don’t overpack your schedule. Drop a class or extracurricular commitment if you no longer have time for fun, friends, meals, exercise, or sleep.

Attend events on campus and across the Charles. Explore library treasures.

Joseph blatt senior lecturer in education, harvard graduate school of education.

My daughter Talia graduated from the College last year; I graduated so long ago that I no longer divulge the year. But despite the time lapse, we find that our advice for first-years is quite similar. Our joint recommendations:

Your academic experience will be far richer if you make the effort to get to know some of your professors. Take advantage of office hours — they are often shockingly underattended — and don’t be shy about engaging in conversations that go beyond the boundaries of the course. You can even invite them to dinner, and Classroom to Table will pay!

Think of Harvard as your fifth course (or sixth for the overzealous). The torrent of talks, performances, and other events that flow across campus every week will offer some of the most powerful learning you’ll experience here — along with the chance to meet new people, exercise your body and mind, and indulge in an unbelievable amount of free food.

Explore Harvard’s more than 60 libraries, where you will find treasures not available on screen: wonderfully obscure books, an amazing historical map collection, precious manuscripts, famous people’s recipes … along with brilliant reference librarians who are unfailingly eager to help.

The Red Line, with all its faults, is your ticket to downtown Boston. Don’t miss the Freedom Trail, art museums, music venues, and cuisines from around the world. And that way, when people ask, “Where do you go to college?” and you respond “er … Boston,” you’ll be closer to telling the truth.

This is starting to sound too much like “Let’s Go,” so we leave you with two thoughts focused on your studies: Pay attention to how you learn and choose courses and classrooms that make you happy; and don’t compare yourself to your peers — be pleased for their success, not threatened by it.

Ask for help. Study abroad.

Gabriela soto laveaga professor of the history of science, antonio madero professor for the study of mexico, department of the history of science.

I would definitely tell first-year students to think of asking for help as a necessary part of being successful at Harvard and beyond. Time and again, I see that the most successful Harvard students are the ones who not only reached out for help (either with writing, math, mental health, for instance), but knew who or where to ask. First-years need to explore the support network that is offered to them and use it. It is there for them.

Also, they must all do a study abroad while they are students.

Try everything. Share projects. Requirements can wait.

Stephanie burt donald p. and katherine b. loker professor of english, department of english.

Starting with academics, and moving into the rest of your life:

DO: Take classes that look interesting, especially if they’re small. Your first year can let you explore your actual interests, even if they’re not connected to your planned concentration, grad school, or career. You might even change those plans to reflect a talent, or a power, or a strong interest you didn’t know you had!

DO: Shop. We’ve got an add-drop period for a reason. Listen to the professor and see if you vibe with that teaching style. Speak with the professor if you like! And talk to non-first-years who’ve taken courses with that professor before.

DON’T: Try to get all your requirements out of the way early. You can take the requirements that don’t matter to you (for most people those are gen eds) junior or senior year when your other classes are big-deal, high-effort courses in your concentration. There’s no reason to take more than one gen ed in a term: Especially curious or ambitious first-years might take none.

DO: Study the past. Don’t confine yourself to the present as you choose courses in the arts and humanities. A lot of fascinating people died a long time ago. Some of them made some cool stuff.

DO: Try everything, including stuff you didn’t think you were good at. Many of us got to Harvard by choosing, in high school, mostly to do stuff we considered ourselves very good at. You got into Harvard. You have room to experiment. Comp or do something you never thought you could do.

DON’T: Stay on campus all day every day. The musical, literary, theatrical, gamer-nerd, ethno-cultural, culinary, recreational, and technical offerings of the Greater Boston area far exceed what you can find on campus, even though campus has a lot to offer. You may find your favorite new band at the Middle East (the rock club in Central Square, not the geographic region). You could find your new best friend at MIT.

DO: Look for people like you. Intense Dungeons and Dragons players, fashion plates, curling obsessives — Harvard’s big enough that you can probably find at least a few peers.

DON’T: Assume people unlike you won’t hang out with you. Some of the friends you make this year will have backgrounds much like yours. Some very much won’t.

DON’T: Spend all your time studying. Honestly, Harvard students probably spend less time on average studying — especially if you exclude future doctors — than students at some other super-elite colleges, and that’s a feature, not a bug, for Harvard: You’ve got time to meet students who share your ambitions, and take part in massive shared projects, and build what you want to build, and discover what you want to discover, both with, and far away from, classrooms and grades and professors like me.

Share this article

You might like.

Garber says key to greater unity is to learn from one another, make all feel part of community at Morning Prayers talk

Garber to students at Convocation: ‘You will learn more from difficult moments of tension than from easy moments of understanding.’

As a woman, Anne Radcliffe wouldn’t have been able to attend the University when she donated its first scholarship in 1643

Billions worldwide deficient in essential micronutrients

Inadequate levels carry risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes, blindness

You want to be boss. You probably won’t be good at it.

Study pinpoints two measures that predict effective managers

Weight-loss drug linked to fewer COVID deaths

Large-scale study finds Wegovy reduces risk of heart attack, stroke

Ph.D. Job Placement

Students receiving a Ph.D. in Anthropology from Yale go on to teaching and research positions around the world, at a wide variety of institutions—both academic and non-academic. This page lists the dissertation topic, graduation date, and current employment (if known) of Yale Anthropology Ph.D. alumni who received their degrees since 2010.

If you’re an alum and our information about you is incomplete or out of date, please send a note to the department chair and we will be happy to update it.

| Name | Dissertation | Year | Division | Current Position |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tram Luong | The Optics of Hatred: Visualizing the Vietnamese Other in Cambodia | 2023 | Sociocultural | Faculty Member (assistant professor equivalent) in Art and Media and Social Studies, Fulbright University Vietnam |

| Vanessa Koh | On the Ground: Land, Sovereignty, and Terraformation in Singapore | 2023 | Sociocultural & School of the Environment | Postdoctoral Fellow, Mellon Initiative in Architecture, Urbanism and the Humanities, Princeton University |

| Rundong Ning | Rearticulating Work: Entrepreneurship and Work-Based Identity in Contemporary Congo-Brazzaville | 2023 | Sociocultural | |

| Carlye Chaney | Environmental Exposures from the Local to the Global: A Comparison of the Experiences and Consequences of Exposure Among the Qom of Formosa, Argentina, and Residents of New Haven, Connecticut | 2023 | Biological | Postdoctoral Scholar, University of Missouri, Columbia |

| Name | Dissertation | Year | Division | Current Position |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amanda Leiss | Paleoenvironmental context of Early Stone Age Archaeology: An Analysis of the Gona Fauna Between ~3 and 1 Ma | 2022 | Biological | Adjunct Professor, Anthropology, Southern Connecticut State University |

| Name | Dissertation | Year | Division | Current Position |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tri Phuong | The Politics of Play: Digital Youth, New Media, and Social Movement in Contemporary Vietnam | 2021 | Sociocultural | Assistant Professor, Pacific and Asian Studies, University of Victoria, BC, Canada |

| Jessica Cerdeña | Onward: An Ethnography of Latina Migrant Motherhood During the COVID-19 Pandemic | 2021 | Medical Anthropology (MD/PhD) | Resident in Family Medicine, Middlesex Healthcare System |

| Qingzhu Wang | Copper Mining and Bronze Production in Shandong Province: A New Perspective on the Political Economy of the Shang State | 2021 | Archaeology | |

| Aalyia Sadruddin | After-After-Lives: Aging, Care, and Dignity in Postgenocide Rwanda | 2021 | Sociocultural and Medical | Assistant Professor of Sociocultural Anthropology at Wellesley College |

| Elizabeth Berk | Viral Subjects: Stigma, Civil Society Activism, and the Making of HIV/AIDS in Lebanon | 2021 | Sociocultural & Medical | Lecturer, Anthropology, Southern Methodist University |

| Heidi K. Lam | Animating Heritage: Affective Experiences, Institutional Networks, and Themed Consumption in the Japanese Cultural Industries | 2021 | Sociocultural | Researcher, ReD Associates |

| Amy Leigh Johnson | State Re-Making: Federalism, Environment, and the Aesthetics of Belonging in Nepal | 2021 | Sociocultural & School of the Environment | |

| Emily Nguyen | Urban Dreams and Agrarian Renovations: Examining the Politics and Practices of Peri-Urban Land Conversion in Hanoi, Vietnam | 2021 | Sociocultural | Qualitative Research Expert, World Food Programme Headquarters, Rome |

| Chandana Anusha | The Living Coast: Port Development and Ecological Transformations in the Gulf of Kutch, Western India | 2021 | Sociocultural | |

| George Bayuga | How to Make a Nun: Gender and the Infrastructure of the Catholic Church in China | 2021 | Sociocultural | |

| Meredith Mclaughlin | Moral Claims: Ethics and the Pursuit of Welfare in Rural Rajasthan, India | 2021 | Sociocultural | . |

| Name | Dissertation | Year | Division | Current Position |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hatice Erten | At Least Three Children: Politics of Reproduction, Health and Care in Pronatalist Turkey | 2020 | Sociocultural and Medical | |

| Jacob Rinck | The Future of Political Economy: International Labor Migration, Agrarian Change and Shifting Developmental Visions in Nepal | 2020 | Sociocultural | Postdoctoral Fellow, Asian Research Institute, National University of Singapore |

| Kyle Wiley | Intergenerational Consequences of Interpersonal Violence: The Role of Fetal Programming | 2020 | Biological | Postdoc at UCLA Biobehavioral Sciences |

| Michelle Young | Interregional interaction, social complexity and the Chavin horizon at Atalla, Huancavelica, Peru | 2020 | Archaeology | |

| Keahnan Washington | There Has to Be Reciprocity’: Love-Politics, Expertise, and the Reimagination of Political Possibility with Formerly-Incarcerated Organizers in New Orleans | 2020 | Sociocultural & AFAM | |

| Alyssa Paredes | Plantation Peripheries: The Multiple Makings of Asia’s Banana Republic | 2020 | Sociocultural | |

| Kristen McLean | Fatherhood and Futurity: Youth, Masculinity, and Contingency in Post-crisis Sierra Leone | 2020 | Biological |

| Name | Dissertation | Year | Division | Current Position |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elaine Guevara | Genomics of Primate Longevity | 2019 | Biological | |

| Myles Lennon | Affective Energy: Intersectional Solar Transitions in a Late Liberal Metropolis | 2019 | Sociocultural & Forestry and Environmental Studies | |

| Amelia Sancilio | Is Accelerated Senescence a Cost of Reproduction? An Analysis of Life History Trade-offs in Post-menopausal Polish Women | 2019 | Biological | |

| Kendall Arslanian | Early Life In Samoa: Nutritional And Genetic Predictors Of Infant Body Composition And An Analysis Of Maternal Attitudes Toward Breastfeeding | 2019 | Biological | Program Manager, American Academy of Pediatrics |

| Louisa Cortesi | Living in Unquiet Waters: Knowledge and Technologies in North Bihar | 2019 | Sociocultural | |

| Tanambelo Vassili Reinaldo Rasolondrainy | Resilience and Niche Construction in the face of Climate Variability, Southwest Madagascar | 2019 | Archaeology | , Chief Advisor, Centre de Documentation et de Recherche sur l’Art et la Tradition Orale de Madagascar |

| Samar Al-Bulushi | Citizen-Suspect: Publics, Politics, and the Transnational Security State in East Africa | 2018 | Sociocultural | |

| Gabriela Morales | Decolonizing Medicine: Care and the Politics of Well-Being in Plurinational Bolivia | 2018 | Sociocultural | |

| Andrew Womack | Crafting Community: Exploring Identity and Interaction through Ceramics in Early Bronze Age Gansu, China | 2018 | Archaeology | |

| Elliot Prasse-Freeman | Resisting (without) Rights - Activists, Subalterns, and Political Ontologies in Burma | 2018 | Sociocultural | |

| Sayd Randle | Replumbing the City:Water and Space in Los Angeles | 2018 | Sociocultural | Assistant Professor of Urban Studies, College of Integrative Studies, Singapore Management University |

| Sahana Ghosh | Borderland orders: Gendered Geographies of Mobility and Security Across the India-Bangladesh borderlands | 2018 | Sociocultural | |

| Colin Thomas | Las Minas Archaeometallurgical Project | 2018 | Archaeology | |

| Dorsa Amir | Adaptive Variation in Risk & Time Preferences: An Evolutionary and Cross-Cultural Perspective | 2018 | Biological | |

| Daniela Wolin | Everyday Stress, Exceptional Suffering: Bioarchaeology of Violence and Personhood in Late Shang, China | 2018 | Archaeology | Post-doctoral Researcher, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem |

| Rose Keimig | Growing Old in China’s New Nursing Homes | 2018 | Sociocultural | |

| Ryan Jobson | Fueling Sovereignty: Energy, Infrastructure, and State Building in Trinidad and Tobago | 2017 | Sociocultural | |

| Erin Burke | Broad Engagement of the Neuroendocrinology of Parenting: Evidence from Male Same-Sex Parents | 2017 | Biological | Senior Manager, Head of Partnership Development at Variant Bio |

| Jessica Newman | Making the Mere Celibataire: NGOs, Activism, and Single Motherhood in Morocco | 2017 | Sociocultural | |

| Aniket Pankaj Aga | Genetically Modified Democracy: The Sdence and Politics of Transgenic Agriculture in Contemporary India | 2017 | Sociocultural | Assistant Professor of Geography, State University of New York, Buffalo |

| Hosna Sheikholeslami | Thinking through Translation: Translators, Publishers, and the Formation of Publics in Contemporary Iran | 2017 | Sociocultural | |

| Elizabeth Miles | Men of No Value: Contemporary Japanese Manhood and the Economies of Intimacy | 2017 | FAS | Faculty Member (assistant professor equivalent) in Social Science |

| Sierra Bell | Apocalyptic Politics: Liberty and Truth in Tea Party America | 2017 | Sociocultural | |

| Maria Sidorkina | Kholivar: New Projects of Belonging on the Russian Periphery | 2017 | Sociocultural | |

| Jessamy Doman | The paleontology and paleoecology of the late Miocene Mpesida Beds and Lukeino Formation, Tugen Hills succession, Baringo, Kenya | 2017 | Archaeology | Anthropologist, Kenyon International Emergency Services |

| Qiubei Amy Zhang | Matter Transformed: Remaking Waste in Postreform China | 2017 | Sociocultural & Forestry and Environmental Studies | |

| Ainur Begim | Investing for the Long Term: Temporal Politics of Retirement Planning in Financialized Central Asia | 2016 | Sociocultural | |

| Andrew Carruthers | Specters of Affinity: Clandestine Movement and Commensurate in the Indonesia-Malaysia Borderlands | 2016 | Sociocultural | |

| Adrienne Jordan Cohen | Improvising the Urban:Dance, Mobility, and Political Transformation in the Republic of Guinea | 2016 | Sociocultural | |

| Kristina Douglass | An Archaeological Investigation of Settlement and Resource Exploitation Patterns in the Velondriake Marine Protected Area, Southwest Madagascar, ca. 900 BC to AD 1900 | 2016 | Archaeology | Associate Professor of Climate, Columbia Climate School |

| Ivan Ghezzi | Chankillo as a Fortification and Late Early Horizon (400-100 BC) Warfare in Casma, Peru | 2016 | Archaeology | |

| Yu Luo | Ethnic by Design: Branding a Buyi Cultural Landscape in Late-Socialist Southwest China | 2016 | Sociocultural | |

| Timothy Webster | Genomic of a Primate Radiation: Speciation and Diversification in the Macaques | 2015 | ||

| Lucia Cantero | Specters of the Market: Consumer-Citizenship and the Visual Politics of Race and Inequality in Brazil | 2015 | Sociocultural | |

| Sarah LeBaron von Baeyer | National Worlds, Transnational Lives: Nikkei-Brazilian Migrants in and of Japan and Brazil | 2015 | Sociocultural | |

| Michael Degani | The City Electric: Infrastructure and Ingenuity in Postsocialist Tanzania | 2015 | Sociocultural | Assistant Professor of Social Anthropology, University of Cambridge, U.K. |

| Dana Graef | Isles of Green: Environmentalism and Agrarian Change in Costa Rica and Cuba | 2015 | Sociocultural | |

| Oscar Prieto | Gramalote: Domestic Life, Economy and Ritual Practices of a Prehispanic Maritime Community | 2015 | Archaeology | |

| Atreyee Majumder | Being Human in Howrah: On Historical Sensation and Public Life in an Industrial Hinterland | 2014 | Sociocultural | |

| Abigail Dumes | Divided Bodies: The Practice and Politics of Lyme Disease in the United States | 2014 | Sociocultural | |

| Sarah Osterhoudt | The Forest in the Field: The Cultural Dimensions of Agroforestry Landscapes in Madagascar | 2014 | Sociocultural | |

| Vikramaditya Thakur | Unsettling Modernity: Resistance and Forced Resettlement Due to Dam in Western India | 2014 | Sociocultural | |

| David Kneas | Substance & Sedimentation: A Historical Ethnography of Landscape in the Ecuadorian Andes | 2014 | Archaeology | |

| Ana Lara | Bodies & Souls: LGBT Citizenship and the Catholic State | 2014 | Sociocultural | |

| Ryan Clasby | Exploring Long Term Cultural Developments and Interregional Interaction in the Eastern Slopes of the Andes: A Case study from the site of Huayurco, Jaén Region, Peru | 2014 | Archaeology | |

| C. Anne Claus | Drawing Near: Conservation By Proximity In Okinawa’s Coral Reefs | 2014 | Sociocultural | Associate Professor (with tenure), Department of Anthropology, American University |

| Hande Ozkan-Zollo | Cultivating the Nation in Nature: Forestry and Nation-Building in Turkey | 2013 | Sociocultural | |

| Joshua Rubin | Confronting an Art of Uncertainty: Rugby, Race and Masculinity in South Africa | 2013 | Sociocultural | |

| Susanna Fioratta | States of Insecurity: Migration, Remittances, and Islamic Reform in Guinea, West Africa | 2013 | Sociocultural | |

| Shaila Seshia Galvin | State of Nature: Agriculture, Development and the Making of Organic Uttarakhand | 2013 | Sociocultural | |

| Isaac Gagne | Private Religion and Public Morality: Understanding Cultural Secularism in Late Capitalist Japan | 2013 | Sociocultural | |

| Darian Parker | Topological Densities: An Existential Psychoanalytic Ethnography of a Title 1 School in New York City | 2013 | Sociocultural | , , |

| Radhika Govindrajan | Beastly Intimacies: Human-Animal Relations in India’s Central Himalayas | 2013 | Sociocultural | |

| Stephen Chester | Origin and Early Evolutionary History of Primates: Systematics and Paleobiology of Primitive Plesiadapiforms | 2013 | Biological | |

| Alexander Antonites | Political and Economic Interactions in the Hinterland of the Mapungubwe Polity, c. AD 1200-1300, South Africa | 2012 | Archaeology | Senior Lecturer, Department of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Pretoria |

| Jason S. Nesbitt | Excavations at Caballo Muerto: An Investigation into the Origins of the Cupisnique Culture | 2012 | Archaeology | |

| Sheridan M. Booker | Spanish Dance and Transformations in the Cuban Public Sphere:Race, Ethnicity, and the Performance of New Socio-Economic Differences, 1988-2008 | 2012 | Sociocultural | , Founder & Director WURArts Consulting |

| Nathaniel M. Smith | Right Wing Activism in Japan and the Politics of Futility | 2012 | Sociocultural | |

| Emily Goble Early | Paleontology of the Chemeron Formation, Tugen Hills, Kenya, with Emphasis on Faunal Shifts and Precessional Climatic Forcing | 2012 | ||

| Kelly Hughes | Spatial Representations of Objects by Non-human Primates: Evidence from Rhesus Macaques (Macaca mulatta) and Brown Capuchins (Cebus apella) | 2012 | Biological | Research Scientist III, Sage Program, Minnesota Department of Health |

| Minhua Ling | City Cowherds: Migrant Youth Coming of Age in Urban China | 2012 | Sociocultural | |

| Christina H. Moon | Material Intimacies: The Labors of Creativity in the Global Fashion Industry | 2011 | Sociocultural | |

| Douglas Park | Climate Change, Human Response and the Origins of Urbanism at Timbuktu: Archaeological Investigations into the Prehistoric Urbanism of the Timbuktu Region on the Niger Bend, Mali, West Africa | 2011 | Archaeology | Principal Consultant at ERM: Environmental Resources Management |

| Alethea Murray Sargent | Learning to Be Homeless: Culture, Identity, and Consent Among Sheltered Homeless Women in Boston | 2011 | Sociocultural | |

| Katie Marie Binetti | Early Pliocene hominid paleoenvironments in the Tugen Hills, Kenya | 2011 | Biological | |

| Myra Jones-Taylor | Blank Slates: Boundary-work and Neoliberalism in New Haven Childcare Policy | 2011 | Sociocultural | |

| Nazima Kadir | The Autonomous Life? : Paradoxes of Hierachy, Authority, and Urban Identity in the Amsterdam Squatters Movement | 2010 | Sociocultural | |

| Brenda Khayanga Kombo | The Policing of Intimate Partnerships in Yaoundé, Cameroon | 2010 | Sociocultural | |

| Yuichi Matsumoto | The Prehistoric Ceremonial Center of Campanayuq Rumi: Interregional Interactions in the South-central Highlands of Peru | 2010 | Archaeology | |

| Nana Okura Gagné | “Salarymen” in Crisis?: The Collapse of Dominant Ideologies and Shifting Identities of Salarymen in Metropolitan Japan | 2010 | Sociocultural | |

| Durba Chattaraj | Roadscapes: Everyday Life Along the Rural-Urban Continuum in 21st Century India | 2010 | Sociocultural | |

| Omolade Adunbi | Belonging to the (S)oil: Multinational Oil Corporations, NGOs and Community Conflict in Postcolonial Nigeria | 2010 | Sociocultural | |

| Annie Harper | The Idea of Islamabad: Unity, Purity and Civility in Pakistan’s Capital City | 2010 | ||

| Ajay Gandhi | Taming the Residual Workers, Animals and Others in Old Delhi | 2010 | Sociocultural | |

| Csilla Kalocsai | Corporate Hungary: Recrafting Youth, Work, and Subjectivity in Global Capitalism | 2010 | Sociocultural |

- Perm Krai Tourism

- Perm Krai Hotels

- Perm Krai Bed and Breakfast

- Flights to Perm Krai

- Perm Krai Restaurants

- Things to Do in Perm Krai

- Perm Krai Travel Forum

- Perm Krai Photos

- Perm Krai Map

- All Perm Krai Hotels

- Perm Krai Hotel Deals

Trains bypassing Perm-2 - Perm Krai Forum

- Europe

- Russia

- Volga District

- Perm Krai

Perm Krai Hotels and Places to Stay

- GreenLeaders

In Memoriam

Robert paynter, professor emeritus of anthropology (1949-2023).

It is with sadness to share the news of Professor Emeritus Bob Paynter’s passing on April 30, 2023

For those who didn’t know him, Bob was a historical archaeologist who made profound contributions to this department, as well as to the discipline. He received his PhD from UMass in 1980 and taught here between 1981-2015 after a stint at Queens College and the Graduate Center at CUNY.

In terms of his intellectual legacy, Bob is best known for his use of critical theory and social activism within his investigation of the past. He made important contributions to the archaeology of capitalism, undertaking extensive historical archaeological research at two important sites - the W.E.B. Du Bois’ Home site and Deerfield Village.

On campus, he undertook critical work on repatriation and was deeply involved in the faculty union (MSP).

Those of us who knew him remember him as a tireless, kind, and generous mentor and colleague. His passing is a tremendous loss on so many levels and he will be greatly missed.

Obituary Berkshire Eagle "Remembering Bob Paynter"

Oriol Pi Sunyer, Professor Emeritus of Anthropology (1930-2023)

Authored by Jackie Urla, for Inside UMass

Emeritus Professor Oriol Pi Sunyer passed away Tuesday, April 11, 2023, in Amherst. Professor Pi Sunyer had a long and distinguished career at UMass (1967-2008) and was one of the founding members of the Anthropology Department.

Oriol Pi-Sunyer was born in Barcelona on January 16, 1930, to a family of intellectuals, scientists, writers, and politicians. His father, Carles Pi i Sunyer was trained as an engineer and became a noted political leader in Catalonia, including Mayor of the city of Barcelona (1934-37) and Minister of Culture, in the Catalan Govern de la Generalitat, 1937-1940.

The Spanish Civil War (1936-39) sent Oriol and his family into exile, first to France, then to England, and finally to Latin America. He received his primary education in England, his undergraduate education at Mexico City College, and his PhD from Harvard in 1962. He did his dissertation fieldwork in Oaxaca, Mexico, on rural economy and social change. His first teaching position was at the University of New Brunswick, then he moved to what was then the Case Institute of Technology. He joined the University of Massachusetts in 1967, as a founding member of the newly formed anthropology department. Within the department, he helped to co-found the unique European Studies field school and supervised many cohorts of students in learning the fundamentals of ethnographic research.

Throughout his career, Professor Pi Sunyer turned his focus to the study of nationalism and collective identity in Catalonia. He made influential contributions to the study of ethnic nationalism while also continuing his interests in political economy. One of these was deeply influential not only in the US but in Europe as well: The Limits of Integration: Ethnicity and Nationalism in Modern Europe, Oriol Pi-Sunyer, ed., Department of Anthropology Research Reports Number 9, Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts, 1971. He was also a pioneering figure in the creation of tourism studies. With his colleagues UMass Brooke Thomas and Henry Geddes, and the late Mexican anthropologist Magalí Daltabuit, in the late 1980s he embarked on what became a 20-year longitudinal study of the Yucatan town of Tulum, now a fashionable tourist destination but all those years ago a ramshackle Wild-West sort of place.

One of the things that distinguished Oriol as a teacher was the care he put into the supervision of MA theses and Ph.D. dissertations, and his students remember him with great affection for this. He retired in 2008. In 2018, the Department created the Oriol Pi Sunyer Dissertation Prize in his honor. His passing is a profound loss to all who knew him.

UMass New Article Obituary

Machmer Hall 240 Hicks Way Amherst, MA 01003-9278 Tel: 413.545.2221 Fax: 413.577.4217

Advertisement

The entangled human being – a new materialist approach to anthropology of technology

- Original Research

- Open access

- Published: 02 September 2024

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Anna Puzio ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8339-6244 1

19 Altmetric

Technological advancements raise anthropological questions: How do humans differ from technology? Which human capabilities are unique? Is it possible for robots to exhibit consciousness or intelligence, capacities once taken to be exclusively human? Despite the evident need for an anthropological lens in both societal and research contexts, the philosophical anthropology of technology has not been established as a set discipline with a defined set of theories, especially concerning emerging technologies. In this paper, I will utilize a New Materialist approach, focusing particularly on the theories of Donna Haraway and Karen Barad, to explore their potential for an anthropology of technology. I aim to develop a techno-anthropological approach that is informed and enriched by New Materialism. This approach is characterized by its relational perspective, a dynamic and open conception of the human being, attention to diversity and the dynamics of power in knowledge production and ontology, and an emphasis on the non-human. I aim to outline an anthropology of technology centered on New Materialism, wherein the focus, paradoxically, is not exclusively on humans but equally on non-human entities and the entanglement with the non-human. As will become clear, the way we understand humans and their relationship with technology is fundamental for our concepts and theories in ethics of technology.

Similar content being viewed by others

The Anthropology of Technology: The Formation of a Field

Exploring Human Nature in a Technology-Driven Society

Technology and the Lifeworld in Miguel Baptista Pereira

Explore related subjects.

- Artificial Intelligence

- Medical Ethics

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The swift pace of technological progress has rekindled interest in anthropology, meaning that, in light of new technologies, we reflect on what it means to be human. Technological advancement gives rise to several questions in society: What sets humans apart from technology? What capabilities are unique to humans? Will technology replace humans? Can robots possess consciousness or intelligence that were previously attributed only to humans? And how will humans and technology differ in the future? Particularly, humanoid robots prompt us to revisit the foundational question of what it means to be human [ 1 ].

Moreover, in AI research and the ethics of technology, many anthropological themes are addressed, such as anthropomorphism, human or computer metaphors, the relationship between humans and technology, the differences between them, and their collaboration in various areas of life [ 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 ]. Additionally, many anthropological statements serve as the basis for ethical reflections. For example, claims about how we should morally interact with new human-like technologies, such as social robots, are derived from definitions of what constitutes human consciousness or intelligence [ 1 ]. That is, what it means to be human today plays a significant role in the philosophy and ethics of technology.

Even though there is a fundamental need for anthropological orientation in society and research, the philosophical anthropology of technology does not exist as an established discipline, at least not in relation to emerging technologies. Anthropological concepts from famous thinkers like Plessner [ 11 , 12 ], Scheler [ 13 ] or Gehlen [ 14 ] were developed many years ago, referring to different societal situations and entirely different technologies. Therefore, in this paper, I will develop a contemporary approach to the anthropology of technology that considers current conceptions of the human and present-day technologies. To this end, I will apply a New Materialist approach, referring especially to the theories of Haraway and Barad, and will demonstrate how New Materialism can contribute to a contemporary philosophical anthropology of technology.

Why New Materialism? When I entered the Blackwell’s Bookshop in Oxford, I encountered an abundance of books about non-human entities. Even though not all explicitly relate to New Materialism, they share its language and thoughts: titles discussing “Entangled Life. How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds, and Shape Our Futures” [ 15 ], “Other Minds” [ 16 ] of octopuses, “The Mind of a Bee” [ 17 ], “The Inner Life of Animals” [ 18 ], “Metazoa: Animal Minds and the Birth of Consciousness” [ 19 ], “When Animals Dream” [ 20 ], “An Immense World: How Animal Senses Reveal the Hidden Realms Around Us” [ 21 ], and “The Hidden Life of Trees: What They Feel, How They Communicate” [ 22 ]. Studies on the non-human are on the rise, and there is a growing accumulation of insights that environmental studies, animal studies, and many other fields have long highlighted: we need to think and speak differently about the non-human, its capabilities, its place in the world, and our relationships with it than we are used to do. To reflect on the human being, it is crucial to reflect on the non-human. New Materialism does precisely this by reconsidering the relationship between humans and non-humans, bringing the non-human and our relationship with it into focus. I will thus propose an anthropology of technology with New Materialism at its core, where paradoxically, the focus is not solely on humans but equally on non-human entities and their entanglement with the human.

Another reason why New Materialism is suitable for a contemporary anthropology of technology is that it draws attention to power relations, discrimination, and the diversity of humans and bodies, which is highly relevant for today’s philosophy of technology as well as contemporary society.

Given how well New Materialism aligns with certain social movements and the current philosophy of technology, it is not surprising that it is gaining increasing popularity. There are already several introductions to New Materialism [ 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 ], and New Materialism has been received by a wide variety of disciplines, such as political science, psychology, theology, gender studies, health research, sociology, education studies, environmental studies, animal studies, social work, and science and technology studies (e.g., [ 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 ]). The engagement with New Materialism is fundamentally interdisciplinary. Moreover, a New Materialist perspective has already been applied to specific technologies and several technological ethical questions [ 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 ]. Haraway has played an important role in feminist approaches to the philosophy of technology and robot ethics [ 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 ].

What is still missing from the discourse so far is the application of New Materialism to the philosophical anthropology of technology. Footnote 1 Although New Materialism itself does not offer a fully developed anthropology, it reflects extensively on the human being and traditional concepts of the human, the human body, and the relationship between humans and the co-world. Additionally, New Materialism is highly theoretical and abstract, resulting in few concrete practical applications. Like other relational approaches, it faces the criticism of being too vague for applied ethics and concrete practice. For example, in robot ethics, it has been debated whether relational approaches should be applied at all or remain subjects of theoretical philosophical discussions [ 47 , 48 ]. Therefore, this article not only aims to provide an anthropological approach informed by New Materialism but also to offer guiding perspectives on how this approach could be concretely applied.

First, in Sect. 2 , I introduce the anthropology of technology and New Materialism, explaining their origins, intellectual traditions, themes, and tasks. In Sect. 3 , I elaborate on and explain key concepts and insights of New Materialism that are particularly relevant to anthropological questions. Based on this, in Sect. 4 , I develop a New Materialist approach to the anthropology of technology, demonstrating what an anthropology of technology informed by New Materialism might look like. To make the highly theoretical New Materialism as applied as possible, I develop a methodological compass for orientation and guidance in anthropological questions, illustrating this with examples of contemporary technologies. Finally, I summarize my findings in the conclusion in Sect. 5 and identify questions for future research.

2 Introducing Anthropology of Technology and New Materialism

2.1 anthropology of technology.

Philosophical anthropology of technology reflects on the human being within the context of technology. A look at the history of technology reveals that the understanding of what it means to be human is related to the technologies of the time and changes in relation to and interaction with them. The respective inventions of the time, such as the clock, the steam engine, or the computer, have always influenced how humans understand themselves and their bodies. For example, Descartes understood the human body as a clockwork mechanism, and later, computer models gained significance in understanding the human mind [ 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 ]. Today, it is human brain interfaces, generative AI, large language models, self-tracking technologies and humanoid robots that pose new challenges to our understanding of what it means to be human.