Soviet Education

on the World Today

MANY Soviet refugees in Western Europe and America count the Soviet system of education as the best feature of the Soviet social order. Certainly tremendous emphasis is placed upon education both by the rulers and by the ruled. The regime has an immediate interest in the training of specialists to carry out its program of rapid economic, political, and military expansion, as well as a long-range interest in molding the “new Soviet man.” The people have different but parallel interests: to attain the economic and social privileges of the new Soviet intelligentsia and to satisfy their own genuine thirst for knowledge.

Soviet leaders have given no indication that they share the fear attributed to an early nineteenth century tsarist minister of education, that “to teach the mass of people, or even the majority of them, how to read will bring more harm than good.” Despite rapid strides toward popular education in the latter nineteenth and early twentieth century, 67 per cent of the people of Russia were illiterate in 1914. In 1939 less than 20 per cent were illiterate, and of those more than half were over fifty years of age. With the end of World War II, strong measures were undertaken to combat increases in illiteracy caused by wartime disruptions of schooling.

The reduction of illiteracy has been accomplished largely by the introduction of universal compulsory education through the seventh grade. The school population of Russia in 1914 was under 8 million; in 1939, with a total population increase of about 20 per cent, the school population was over 32 million.

Equally impressive is the increase in facilities for higher education. In 1914 there were in Russia about 90 institutions of higher education, with about 110,000 students. In 1952 there were some 900 institutions of higher education, with about 974,000 full-time students.

A small percentage of Soviet children between the ages of three and seven go to kindergarten, for which a small tuition fee must be paid. Compulsory schooling starts at the age of seven, and continues through seven grades. Those who intend to go on enter so-called ten-year schools, instead of the seven-year schools. The avowed aim of Soviet educators, from the beginning, has been to make the ten-year education compulsory. Nevertheless, in 1940 tuition fees — 200 rubles a year in Moscow, Leningrad, and the capitals of the republics, 150 rubles elsewhere — were introduced for the eighth, ninth, and tenth grades, with exemptions for certain groups, such as children of disabled veterans. Even before this, however, less than 20 per cent went on from seventh grade to “junior high.”

Some—probably less than 8 per cent—of the graduates of the seven-year school go to special four-year professional and technical high schools (technicums), to be trained as junior specialists in some branch of science, industry, the arts, medicine, education, and the like. There the tuition fees are the same as for the eighth, ninth, and tenth grades.

Something like 20 per cent of the graduates of the seven-year school are conscripted into the State Labor Reserves for four years, where they receive free on-the-job schooling.

Soviet colleges

Upon graduation from ten-year secondary schools and from professional and technical high schools (and usually after two years of military training), roughly one out of five enters higher educational institutions for specialized training. Admission is on the basis of nation-wide competitive examinations. Tuition fees are from 300 to 500 rubles a year — again with exemptions for certain groups, including Heroes of the Soviet Union and Heroes of Socialist Labor as well as “A ” students. Stipends are paid to “good” students, who comprise about 80 per cent of the total number.

As in Europe generally, there is no liberal arts college. A higher educational institution falls into one of the following categories: industry and construction, transport and communications, agriculture, public health, teacher training, social sciences, the arts. The emphasis is on the training of specialists— though that training is by no means narrow. Only about 10 per cent of the Soviet colleges are devoted to either the arts or the social sciences.

Moscow University, with over 14,000 students, including those taking correspondence courses, has eleven different divisions and trains students in fifty different specialties. Leningrad University is slightly larger. Other large universities are at Tiflis, Kiev, Riga (once Latvian), and Lvov (once Polish). All told there are twenty-three city universities.

The organization of Soviet schools and colleges is highly centralized. The general pattern is set by the Council of Ministers of the U.S.S.R., which issues decrees, allocates funds, and determines basic educational policies. Institutions of higher education are directly under the All-Union Ministry of Higher Education. Most of the other schools are under the ministry of education of the republic in which they are situated. Teachers are appointed and given their salaries — which are quite low in the Soviet scale—by the ministry through its local branches.

What they study

The ministries of education implement decisions of the Council of Ministers through detailed instructions which cover every aspect of the curriculum. Each course has its syllabus, from first grade up through postgraduate studies. There is no choice of subjects. From the fourth grade on there are national examinations, written and oral, held at particular times throughout the country.

At the end of the ten-year school, students are examined in the following subjects: Russian language, literature, mathematics (algebra, geometry, trigonometry), physics, chemistry, history (history of the U.S.S.R., modern history), and a foreign language. In non-Russian-speaking areas an examination is also given in the students’ native language. Besides the subjects in which there are examinations before graduation, the ten-year school curriculum includes natural history, geography, Constitution of the U.S.S.R., astronomy, military and physical training, design, drawing, and singing.

Since 1940, either English, German, or French has been required from the fifth grade on. Which language is taught in any school depends on the teacher; in one school it may be English only, in another German. In addition, there is at least one Soviet school where the language of instruction is English, and the students while in school are supposed to converse with each other only in English. Latin, which was reintroduced in the law schools and some other higher educational institutions in the thirties, was in 1952 restored in the secondary schools as well.

Dewey in Russia

With education as with almost everything else of importance in Soviet society, it has not always been so. Soviet education in the twenties and early thirties was dominated by radical ideas similar to those which have caused a stir in the United States. Emphasis was on “spontaneous education,” “learning from life”; the classroom was conceived as a kind of laboratory in which the teacher organized the work around projects, many of which were left to the pupils’ own initiative. Instruction was played down. Special subjects were not taught, but instead were supposed to be learned incidentally, by “doing.” American educational experiments, such as the Dalton Plan evolved by Helen Parkhurst in Dalton, Massachusetts, and others undertaken by the followers of John Dewey, had a great influence on this first phase of Soviet educational development.

Characteristically, Soviet extremism made our reforms seem modest. The Soviets anticipated the gradual “withering away” of the school altogether.

Hy a series of sweeping decrees starting in 103*2 and continuing through 1949 and 1914, Soviet progressive education has been almost entirely scrapped. A 1992 decree abolished the Dalton Plan and the project method, and introduced the three IPs. In 1994 a decree on the teaching of history ordered “the observance of historical and chronological sequence in the exposition of historical events,” and stated that facts, names, and dates should receive due emphasis. In 1997 “polytcchnism” — that is, the organization of the curriculum around labor — was under heavy fire.

Research in problems of polytechnics was abandoned, and subjects of the conventional type came to prevail in the curricula. Iiy 1999 polyteehnism was out, though the name crops up from time to time.

In 1943, separate schools for boys and for girls were introduced in eighty large cities, and later elsewhere. “Coeducation,” said the then People’s Commissar for Education, “makes no allowance for differences in the physical development of boys and girls, for variations required by the sexes in preparing each for their future life work.” However, coeducation was not completely abolished, and there has been a frank and vigorous debate in the Soviet press on the relative merits of the two systems.

The new discipline

The proponents of separate education have stressed the practical desirability of military training for schoolboys and of special training for girls in homemaking and motherhood; more fundamentally, however, the argument has been that separate education promotes better discipline. A few weeks after the decree on separate education, the education authorities promulgated twenty “Rules for School Children,” imposing obligations of conscientious study, good behavior in school and after school, neatness, respect for teachers, and so forth. Rule 9 states that pupils must rise when the teacher enters or leaves the room. Rule 12 requires that upon meeting a teacher in the streets students must give a polite bow, and the boys must remove their hats. A “pupil’s card,” on the back of which the rules are printed, must be carried at all times.

Punishments may now be administered, including admonition, ordering the delinquent to rise from his seat or to leave the room, and expulsion from sehool “The absence of punishment demoralizes the will of the school child,” Pravda stated in 1944. However, corporal punishment is forbidden— though it is apparently sometimes practiced.

The changes in educational policy in the past fifteen to twenty years represent a new philosophy not only of education but of human nature itself. A 1936 decree of the Central Committee of the Party, which attacked psychological testing of school children, established the basic premises of the new educational policy by emphasizing the power of man, by training and self-training, to overcome both his heredity and his environment. Man can lift himself by his bootstraps. More than that, he is responsible for doing so — and for failing to do so. The new policy stresses the responsibility of the pupil. He is no longer an end in himself. His sense of duty must be actively directed and developed.

The schooling of patriots

The political implications of this philosophy are not concealed. The schools are required “to educate the youth in the spirit of unrestrained love for the Motherland and devotion to Soviet authority.” The Young Communist League (Komsomol) with 16 million members between the ages of fourteen and twenty-six is supposed to “show the way” in combating “ideological neutrality.” “The most important task of the Komsomol organization,” states a handbook of 1947, “is to instill into all the youth Soviet patriotism, Soviet national pride, the aspiration to make our Soviet State even stronger.”

The patriotic, military, and moral emphasis of Komsomol and school activity is implemented by indoctrination in Marxist theory, as redefined by Lenin and Stalin. Political propaganda permeates the curriculum. School children are taught the superiority of the “Soviet” biology of Michurin and Lysenko over “bourgeois” biology. In studying Shakespeare, students are taught Marx’s views of the development of English capitalism; Hamlet is seen in part as an exposure of a decadent court aristocracy.

“Marxism-Leninism" is a required course in all Soviet institutions of higher education. Doctors’ dissertations in all fields must be ideologically correct, and there is even some indication that degrees may be revoked years later if “mistakes” in them are discovered.

In many fields, education is open to talent. But “pull" is also an importanl factor: the son of a high Party official gets many privileges in education as elsewhere. Also any indication of dissent from Party doctrine can have serious consequences extending even to imprisonment. For the student without high Party connections, the main criterion in admission to engineering schools or law schools or agronomist schools or teachers colleges is ability, as shown in examinations— including, of course, the examination in Marxism-Leninism.

- HI 446 Revolutionary Russia

- Course Documents

- News and Ramblings

- Karine Ter-Grigoryan

- Katherine Ruiz-Diaz

- Nicholas Richardson

- Emmalee Ortega

- Pamela Orlowska

- Griffin Monahan

- Kaitlyn McDonald

- Nikki-Lynn Marshall

- Agatha Leach

- Jeffrey Hintz

- Mark Faralli

- Amal Chandaria

- Jenna Abbot

Changes in Educational Ideology and Format: 18th to 20th Century Practices

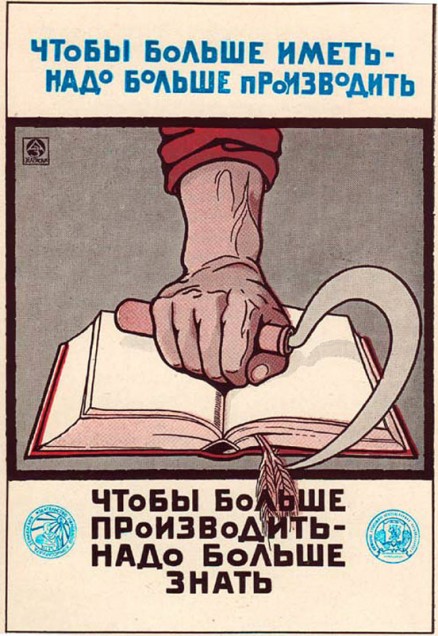

A Soviet poster describing the importance for all to be productive and help build new schools for the proletariat.

This research guide provides a launching point for further study into the topic of eduction in Russia, specifically focusing on the changes that occurred in education due to the transition from Imperial Russia to Bolshevik and Soviet Russia. The time period for this guide begins during the mid 19th century and follows through the mid 20th century. Education in Russia has always been closely associated with society for example it was an exclusive commodity during Imperial Russia when class barriers were firm but as class barrier were broken down during the Russian Revolution education became available to the masses through the Bolshevik ideal of universal education.

Education during Imperial Russia functioned as a means to limit the social mobility of many while it later would serve as a means of social enlightenment during Bolshevik and Soviet Russia. Official state treatment of education shifted with the economic, political, and military issues of each time period. Both Imperial Russia and Soviet Russia utilized education as a means of social control to promote a state agenda or create cohesion. This state approach towards education as a tool begins to demonstrate the complex relationship between state, educational institution, educator, student, and society. To understand the condition of education during these phases of Russian history illuminates the nature of society for the specific period.

Behind many of the major changes in education were state sponsored prerogatives. For example if one where to ask what form did change occur in the educational system? and why did this change occur? The answer would ultimately be tied into a goal or mission of the state. During the reign of Tsar Peter I, compulsory education was initiated as to enlighten and modernize Russian society due to the desire of Peter I to bring Russia out of the dark. Answering the perviously stated questions becomes increasingly difficult as the Bolsheviks and Soviet take power and reshape education. To explain the purpose of universal education one might conclude that it was inline with socialist values but further analysis into this change in educational practice demonstrates state use of education as a means to quell dissenters by creating social cohesion thus solidifying the socialist state.

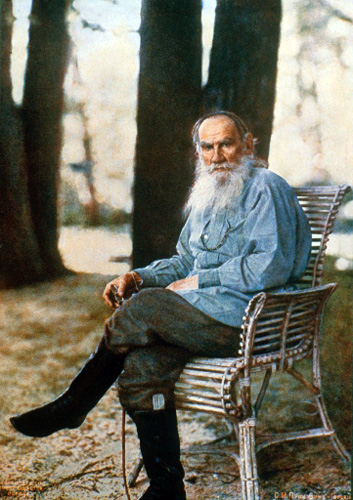

While many of the educational changes that have occurred over time in Russia have been executed a state agenda there have also been many genuine attempts to reformat education for the good of society. During the late 17th centuryTsar Fyodor III valued education and felt compassion for the poor, he took action to create a school specifically for the poor resulting in the creation of The Graeco-Latin-Slavic academy in Moscow. Later on during the mid to late 19th century Count Lev Nikolaevich Tolstoy at the author of War and Peace , opened up his own schools for peasant. The schools he operated utilized organic learning which set them apart from the rigid form of education that was popular in Russia and Europe. The history of Russia education is a constant mixing between hopes and realities as visionaries of educational reform would find their ideas come to life but often to reach an alternative end decided on by external individual or group.

A compilation of sources have been collected on the history of Russian education, the changes of practice, format and ideology of Russia education, and the issues surrounding education at the time. Scholarly journal writings, historiographies, and primary sources make up the majority of the complied sources below. The works are organized under three topics; education during Tsarist Russia, education during early Revolutionary Russia, and Education during early Soviet Russia.

Education During Imperial Russia

Education was predominately exclusive, religious, and limited in length during Imperial Russia. No form of universal public education had yet been established leaving only those with financial means the ability to enroll in educational institutions at the secondary and university level. The gymnasium form of education adopted from Germany provided greater accessibility to education for the elites which contributed to the growth of national culture but also caused a polarization of the educated elite further separating the group from the majority of Russian society. Conservatism was a major theme of these schools both in curriculum and mission. Common curricula at the time focused on classical works, history, political theory, and economics. The common mission of these primary and secondary schools was to mold the student population into a cohesive, mild group that could not become radicalized and cause revolution like that seen in France in 1789. Universities proved a challenge for the Imperial Government and were never tamed due to the influence of intellectuals over the institutions.

Zaikonospassky Monastery that was transformed into the Slavic Greek Latin Academy

- Pipes, Richard. Russia Under The Old Regime. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1974.

Richard Pipes provides an overview of education in Tsarist Russia in Russia Under The Old Regime. He provides valuable insight as he highlights the relationships between peasant, clergy, elite and education. Pipes focuses on the reforms initiated by Peter I in regards to education. Under Peter I a system of mandatory education was created for all young men who upon state inspection would be either sent to school or sent off to service. Peter I had the goal of creating an educated Russian population but his reforms such as compulsory education/state service were some of the most despised of all of the reforms.

- Auty, Robert, and Obolensky, Dimitri. An Introduction to Russian History: Companion to Russian studies. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1976.

Tsar Fyodor III

Tsar Fyodor III possessed an appreciation for Western Europe, this materialized through the creation of a Graeco-Latin-Slavic academy in Moscow. This academic institution was created specifically for the children of poorer classes. Peter I set up ‘cypher’ schools staffed by clergy as part of his compulsory education reform. These schools found little success due to the clergies’ inability to teach secular studies and the elite’s disapproval of mixing of social classes in schools. Other fear of rapid educational expansion most notability included the elite’s fear that a chaotic change of social order would occur. The push for mass education that came from Fyodor III and Peter I continued through the early 20th century increasing literacy from roughly 20% in 1897 to 44% in 1914.

- Freeze, Gregory L. Russia: A History. New York: Oxford University Press: 2002.

Gregory Freeze writes extensively on the condition of Russia from the 16th century through the 20th century. He emphasis on transitions in Russia allows the reader to follow the changing education system. In 1667 Russia acquired the left bank of Ukraine bringing an influx of educated men into Russia promoting a new level of scholarship. While Peter I visited Western Europe he recruited experts from Europe, some of the most influential recruits were Joseph Nye, John Deane, John Perry, and Henry Farquharson all who played a role in building Russia’s new navy. With plans drafted by Peter I, The Imperial Academy of Sciences opened in 1725 that would overtime solidify itself as a reputable institution of higher education in Russia.The Spiritual Regulations of 1721 required an educated, literate clergy to do so a seminary system based on the Jesuit seminary system was adopted and common practice by the 1780s. Alexander I took on the challenge of providing higher education regardless of class for Russian by creating universities in Kharkov, Kazan, and St. Petersburg. The growth of education brought about two forces that would challenge imperialism: nationalism and the desire for participation in politics. During the late 1920s of Russia measures were taken to remove privileged groups from higher education replacing them with working class groups.

- Thaden, Edward. Conservative Nationalism in Nineteenth-Century Russia. Seattle: University of Washington Press,1964.

Conservatism in 19th century Russia can be equated with the phrase Autocracy, Orthodoxy, and Nationality. A major proponent of this conservative push in 19th century Russia was Admiral Alexander Shishkov. Shishkov would influence Russia through his work as Minister of Public Instruction. His attempt to promote Autocracy, Orthodoxy, and Nationality took the form of educating the upper class of Russia to create social cohesion and moral strength for Russia. To do so he worked to replace educational institutions of non-Russian origin (Polish and Catholic) with truly Russian educational institutions. Edward Thaden professor of Russian studies at Pennsylvania State University chronicles the growth of conservatism in 19th century Russia in his work Conservative Nationalism in Nineteenth-Century Russia . His focus towards education during this period of increased conservatism provides a useful timeline of the evolution of education under Tsarist Russia. His use of officials, scholars, and radicals provides a multitude of angles to view this period of change.

- Ringlee, Andrew. The Instruction of Youth in Late Imperial Russia: Vospitanie in the Cadet School and Classical Gymnasium, 1863-1894 . University of North Carolina, 2010.

During the final years of Imperial Russia two starkly contrasting groups of students were produced from the state sponsored schools run by the Ministry of War and by the Ministry of Education. Military cadet schools were run by the Ministry of War while the civilian gymnasium was run by the Ministry of education. Graduates of military cadet schools remained loyal their alma mater years after the collapse of Imperial Russia while graduates of the civilian gymnasium typically renounced former educators and schools. Andrew Ringlee compares the educational methods utilized by the Ministry of War and Ministry of Education during the reigns of Alexander II and Alexander III to understand how participants experienced the two types of institution. An electronic copy if this work can be found h ere .

- Alston, Patrick L. Education and the State of Tsarist Russia. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1969.

Education under Tsarist Russia progressed through several stages growing in sophistication and autonomy. Peter I brought major changes to the educational system of Russia introducing a new sense of enlightenment to the institutions of education. Towards the late 19th century educators began to push back against the grip of the state on education. These efforts for greater autonomy and legitimacy would become engrained values in educators that would remain through the Russian Revolution. This progression can be seen through Patrick Alston’s work Education and the State in Tsarist Russia. Alston takes a chronological approach to depict the relationship between education and the state beginning in the 18th century through 1914. He divides his book to demonstrate the gradual but present growth of the influence of educators in Tsarist Russia.

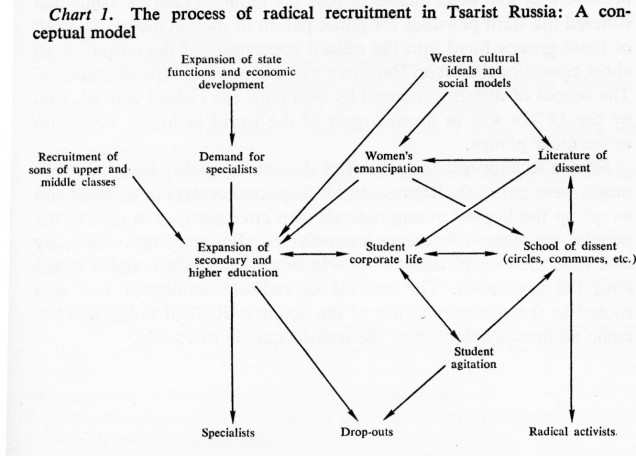

- Brower, Daniel R. Training the nihilists: education and radicalism in Tsarist Russia . Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1975.

Daniel Brower’s Flow Chart of Radicalism

Daniel Brower’s work Training the Nihilists: Education and Radicalism in Tsarist Russia explains the role of formal education in the creation and evolution of radicalism in Russia during the mid to late 19th century. The book is broken up into chapters that focus at first on the smaller groups in Russian society like family and then places focus on larger groups concluding with a newly established society of dissenters. Dissent was a key ingredient in Russia during the late 19th century and early 20th century, this book aims at answering where this dissent came from. Two features of Brower’s work that are most helpful in gaining an understanding of dissent in Russia are survey date from 1840-1870s revealing the level of education for Russian radicals and a flow chart of the development of Russian radicals between 1840-1870.

- Kassow, Samuel D. Students, Professors, and the State in Tsarist Russia . Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989.

Early 20th century Russia was a period of full of different groups functioning as political actors influencing the nature of the Russian state. In Students, Professors, and the State in Tsarist Russia, Samuel Kassow focuses on the interactions of students, universities, and professors with the state. Kassow shows that failure of the tsarist Russian state to recognize the legitimacy of student movements based out of Russian universities. Officials of the state had to find a balance between limiting social unrest produced from universities and educational institutions while not completely crushing education as it was recognized the need for an increase of educated laborers. Professors and the Russian government clashed in ideological purpose for universities. Professors saw universities as models of free research and academic freedom while the government saw the establishment as utilitarian in purpose, raising proper civil servants. An electronic copy of the work can be found here .

- Seregny, Scott. Russian Teachers and Peasant Revolution . Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1989.

Scott Seregny questions the notion of rural teachers as meek, humble, isolated figures in late 19th century Russia.Using accounts of rural teachers, students, and town officials he reveals that rural teachers while late the blossoming period of professionalism in Russia held particular power in organizing an All-Russian Teacher’s Union with strong political aims. To combat this perception of educators, Russian educators became a politically active minority pushing against the Old Regime of the Tsar. Russian teachers like other professions during the late 19th century and early 20th century desired self-definition and became aware that their desires could not be achieved in the current Tsarist system. The climax of the rural teachers’ political efforts occurred in 1905 with the 1905 Revolution but quickly faded with the passing of the year. Seregny dives into the low levels of respect towards rural teachers due to low pay, modest origins, and high levels of bureaucracy.

- Walker, Franklin A. “Enlightenment and Religion in Russian Education in the Reign of Tsar Alexander I.” History of Education Quarterly , Vol. 32, No. 3 (Autumn, 1992), pp. 343-360.

Tsar Alexander I sought to educate his countrymen through a plan to expand public education drafted by Catherine II. The initial aim of this expansion of public education in Imperial Russia was to instill enlightenment ideals in the people of Russia but after the threats created during the Napoleonic wars these aims shifted to creating an obedient, moral society to prevent rebellion. During the years after the French Revolution many blamed a lack of religion as the cause of the Reign of Terror during the French Revolution. Franklin A. Walker investigates the balance of religion and enlightenment in education under the reign of Tsar Alexander the I. The need for obedience reinforced the role of religion in education even as ideals of the enlightenment became increasingly popular in education resulting in unique approach to education. An electronic copy of the article can be accessed here .

- Stillings, Renee. The School of Russian and Asian Studies, “Public Education In Russia from Pete I to the Present.” Last modified December 8, 2005.

Renee Stillings offers a short history of Russian education from the 18th century to the present. Her work provides basic foundational knowledge that aids in later developing a larger understanding of the complexities of the Russia’s educational system. The webpage can be accessed here .

- Brooks, Jeffery. When Russia Learned to Read . (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 2003), 54.

With the end of serfdom in Russia came an explosion of peasant desires for education. Jeffery Brooks presents the growth of peasant education during the late 19th century in his work When Russia Learned to Read . The basic components of education are covered including schools, teachers and curriculum. One of the most significant aspect of the work is Brooks’ analysis on the effects of peasant literacy, concluding the with greater amounts of literacy, the peasantry grew curious and ambitious, desiring a different life compared to their parents.

- Souder, Eric M. The School of Russian and Asian Studies, “Tolstoy’s Peasant Schools at Yasnaya Polyana.” Last modified November 18, 2010.

Count Lev Nikolaevich Tolstoy serves as a example of an early education reformer in Tsarist Russia. Eric M. Souder provides information of Tolstoy’s efforts in education in the article “Tolstoy’s Peasant Schools at Yasnaya Polyana”. Tolstoy became upset with the format of education in Russia and Europe during the mid 19th century as he saw that it was not organic enough and non-conducive to learning. This belief mixed with sympathy for the peasant class of Russia provided Tolstoy the inspiration to form his own school in Yasnaya Polyana. His curriculum expanded further beyond traditional subjects to areas like singing, drafting, and Russian history. Souder’s thorough depiction of Tolstoy’s work in education reveals the attitudes surrounding education and the condition of education during Tsarist Russia. This webpage can be accessed here .

- Tolstoy, Lev. The Complete Works of Count Tolstoy: Pedagogical articles; Linen-measurer. Boston: Dana Estes & Company, 1904.

Count Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy

During his efforts to increase education for Russian peasants, Count Lev Nikolaevich Tolstoy published several works on what he believed the be improvements in the field of education that would benefit Russia and in particular the peasants. He compared educational systems around the world to form his own ideal educational system that he asserted would serve Russia better than the current system. The comparative work conducted by Tolstoy was highly critical of the rigid and at times exclusive nature of European educational system. The American public educational system functioned as the embodiment of the ideal of mass education that Tolstoy strove for in Russia. The works of Tolstoy demonstrate a growing disapproval of the current system of education under the Tsars that would later erupt during the Russian Revolution. Many of the concepts put forth in his works would later emerge in experimental Bolshevik schools during the 1920s. The complete compilation of Tolstoy’s works can be found here .

- McClelland, James C. Autocrats and Academics: Education, Society, and Culture in Tsarist Russia .Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1979.

Inequality in the in quality and accessibility of education during Tsarist Russia is the thematic center of James C. McClelland’s work Autocrats and Academics: Education, Society, and Culture in Tsarist Russia. He asserts that the adoption of educational techniques like the gymnasium from German schools allowed for the development of a national culture but at the expense of widening the gap between social classes. The elite nature of secondary schools and universities during Tsarist Russia produced an intelligentsia that would be disconnected from the majority of Russian society in terms of level of education. This work reveals Tsarist relations with elite education, the pedagogy of elite academic institutions, and student activism.

Education During Early Revolutionary Russia

Revolution provided many educational reformers a time to shine and bring their experimental schools to reality. New educational ideologies and practices were incorporated into schools as new schools were established to provided education to the masses while others were created specifically for groups like proletariats or peasants. The formal curricula of these schools varied greatly due to many schools that were self administered by faculty and that evolutionary nature of education during Revolutionary Russia that constantly updated and shifted. Emphasis shifted from one area to another the focus one year may be instilling socialist ideals in student and in following years the focus may shift to science and technology.

- Pipes, Richard. Russia Under the Bolshevik Regime. New York: Vintage Books, 1995.

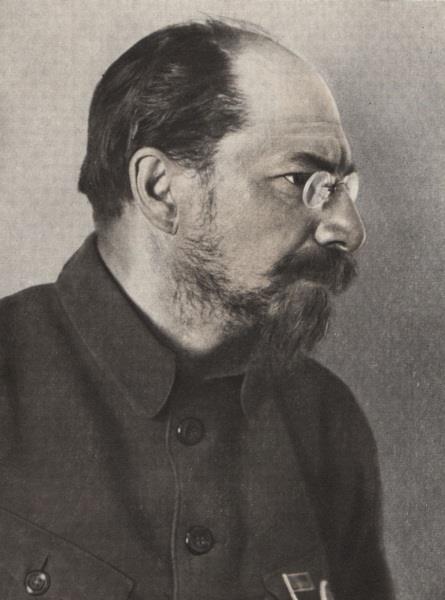

Anatolii Lunacharskii

Richard Pipe enables readers of Russia Under the Bolshevik Regime to follow the systematic changes in education brought about by the Bolsheviks through a detailed chronology of educational change. Vladimir Lenin along with Anatolii Lunacharskii defined the mission for all educational institutions as to raise a new group of human beings superior in culture and intelligence. In 1909 an experimental Bolshevik school was established in Capri with help from Maxim Gorky and Fedor Shaliapin. The goal of this school was to created cadres of educated workers who would then assimilate with the rest of workers to spread their recently acquired knowledge. Lenin was a major opponent to this school because he did not believe that workers possessed the creativity needed for the creation of a new society. Soviet Russia viewed education as vospitanie, meaning upbringing in that education should serve as a means of developing a society of virtuous beings. The key emphasis of this education was science and technology to set the foundations for a technologically advanced Soviet Russia. By 1918 all education became nationalized under the authority of the Commissariat of Enlightenment. A new education system was established leading to a concise pathway from kindergarten to university. While this was a major change other radical philosophies like the establishment of farm and communal worker schools never came to fruition due to fiscal constraints.

- Gleason, Abbott, Kenez, Peter, and Stites, Richard. Bolshevik culture: experiment and order in the Russian Revolution . Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1985.

Lenin recognized the need for a long term educational process, teaching the themes of socialism and political consciousness to society in order to build a socialist society. In Bolshevik culture: experiment and order in the Russian Revolution, education is described as a tool of the Bolsheviks to mold Russia. One means of mass education was printing of propaganda pamphlets but many simply could not read and those who could read responded to the state produced material with disgust. During the Provisional Government, soviet representatives attacked the Ministry of Education for excessive amounts of bureaucracy, lack of progress to increase literacy, failure to increase the status of teachers, and failure to update curriculums to incorporate revolutionary culture. A means of effective communication with the masses came with the popularization of cinema. Authorities were able to produce revolutionary teachings without any words at all through the medium of cinema.

- Rosenberg, William. Bolshevik Vision: First Phase of the Cultural Revolution . (Ann Arbor: Ardis Publishers, 1984), 287.

The Bolshevik ideology is broken down into several sections of society in William Rosenberg’s work Bolshevik Vision: First Phase of the Cultural Revolution. His descriptive writing allows for a vivid depiction of Bolshevik ideology. A section of book titled “United Labor Schools: The Nature of a Communist Education” covers the topics of primary, secondary, and higher education with great detail. Several different school models are described at the primary and secondary level including the United Labor School, the factory school, and the polytechnic school. Higher education is also covered as the nationalization of universities is chronicled, exposing great resistance from the professorate against Lunacharsky’s reforms.

- Fitzpatrick, Sheila. The Cultural Front. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1992.

Sheila Fitzpatrick writes on the cultural revolution in Russia by observing the many dynamic groups and forces that transitioned revolutionary Russia to conservative Stalinist Russia. In her work she analytically depicts the troubles faced by the Bolsheviks in establishing a new education system for the newly created socialist society. The two chapters, ‘Professors and Soviet Power’ and ‘Sex and Revolution’ in The Cultural Front provide deep insight into the struggle for power in education in the new socialist society as intelligentsia were initially removed from education by replaced with frequency. The chapter ‘Sex and Revolution’ uses student health surveys to demonstrate the attitudes of proletariat workers in educational institutions. These attitudes included aversion towards bourgeois professors, apathy towards bookwork, and conservative sexual relationships with peers.

- McClelland, James. “Bolshevik Approaches to Higher Education, 1917-1921.” Slavic Review . no. 4 (1971): 818-831.

During the years 1917 to 1921 the Bolshevik government faced multiple military threats from Imperial Germany, White Russian armies, and movements for national independence. Despite the numerous amount of issues at hand the Bolshevik government was still able to devote time and energy to the revolutionary agenda including educational reform. James McClelland researches three major experimental education systems during this revolutionary period.The first of these initiatives was under the authority of Narkompros which aimed to increase accessibility to higher education, increase enrollment of working class students, and utilize a Marxist agenda. Economic, military, and political strains of the Civil War forced the Bolshevik government to approach educational reform from another angle. The new route to reform in education centered on the vocationalization of education and militarization of students. With the New Economic Plan came a third form of educational reform. This third plan sought to centralize higher education under the authority of the government. McClelland focuses on the relationships between the Bolshevik government and the professors of universities to reveal the complex nature of higher education in revolutionary Russia. An electronic copy of McClelland’s work can be accessed here .

- Rosenberg, William. Bolshevik Visions: The First Phase of the Cultural Revolution in Soviet Russia. Michigan: Ardis Publishers, 1984.

The drive and enthusiasm Anatoly Vasilyevich Lunacharsky possessed during the early period of Bolshevik Russia is capture in William Rosenberg’s work Bolshevik Visions: The First Phase of the Cultural Revolution in Soviet Russia. The work provides a detailed introduction into aims of a new Soviet school that would break away from all of the pervious bourgeois educational institutions. Factory Schools and United Labor Schools were the educational platform set out by Lunacharsky who was eager to aid in creating the new soviet citizen. The work then continues with several speeches by Lunacharsky including his 1918 “Speech to the First All-Russian Congress on Education”, “Basic Principles of the United Labor School”, and “Students and Counter-revolution”. Each of these writings from Lunacharsky show a genuine conviction to change society through education to create an entirely different culture.

- Finkel, Stuart. On the Ideological Front : The Russian Intelligentsia and the Making of the Soviet Public Sphere. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008.

Higher education proved to be one of the last institutions to fall to the control of the Soviets as remnants of the intellectuals’ authority remained. The final push came from the “harsh line” mentality towards universities in that all bourgeois figures and institutions must be removed. Narkompros and Anatoly Lunacharsky contributed to the state seizure of higher education by advising the Party Central Committee of the need to reform higher education. In the way of this desired change was Valdimir Lenin, he believed that there was no need for the immediate take over of universities as the proletariat did not need a high level of education. Lenin’s stance towards higher education was replaced by the “harsh line” when in 1921 a committee was established to discuss reforms of universities.

Education During Early Soviet Russia

As the Bolshevik and Soviet control of Russia solidified came an increased need to maintain this current state and to promote state ideologies. Education became a necessity for the proletariat as the need for an educated proletariat was announced by the state. This period of educational development face a multitude of challenges as the student body rapidly changed from elites to proletariat and peasant students. To extend mass education to proletariat and peasant students by giving these groups preference into secondary schools and universities would lower the standard of education which then would result in the product of a workforce that has received a mediocre education. Educational institutions took the form of vocational schools that set students up for higher education aiming to produce an educated workforce like that never seen before in Russian history. A major problem for educational reforms during this period was parental attitudes towards education as many parents felt that the recently deposed form of education that focused on reading, writing, and arithmetic was proper in curriculum.

- Lipset, Harry. “Education of Moslems in Tsarist and Soviet Russia.” Comparative Education Review . no. 3 (1968): 310-322.

A major shift occurred in the treatment of Muslims in Russia from the Imperial state to Revolutionary and Soviet Russia. Discrimination of minorities during Imperial Russia was commonplace and left Muslims in Russia with insufficient and inadequate education. This limited education for Muslims was improved during Revolutionary and Soviet Russia due to the socialist ideal of universal education. Harry Lipset covers this topic in “Education of Moslems in Tsarist and Soviet Russia”, contrasting the condition of Muslim education under Tsarist Russia and post-Tsarist Russia. To add depth to his work he analyzes the official treatment of other minorities such as Ukrainians and Armenians under each government. Lipset asserts that Muslims were able to make large advances in culture and education through the socialist ideals introduced through the collapse of Imperial Russia. An electronic copy of the article can be accessed here .

- Fitzpatrick, Sheila. The Commissariat of Enlightenment; Soviet Organization of Education and the Arts Under Lunacharsky, October 1917-1921 . Cambridge: University Press, 1970.

The Narkompros was Soviet commission on enlightenment tasked with creating and improving art and education in the newly formed socialist Russia. Sheila Fitzpatrick devotes several chapters to the reformation of education under the authority of the Soviet. Anatoly Vasilyevich Lunacharsky, the commissar of Narkompros set out a multitude of doctrines and declarations that would shape the new educational system in the socialist society. For example, one Lunacharsky’s declarations set up primary and secondary schools so that teachers left to their own devices to organize and operate schools. Fitzpatrick’s work provides a vivid chronology of educational changes that occurred due to the influence of Narkompros.

Education for the Proletariat: To produce more you need to know more.

- Levin, Deana. Soviet Education Today. New York: Monthly Review Press, 1963.

Deana Levin approaches education in the Soviet Union using the historical background of the Russia since 1917. Unlike other works on Soviet education, Soviet Education Today does not compare Soviet education with American education but rather researches the aims and methods of the system. To explain how the Soviet educational system works Levin uses official documents and statements swell as personal observations from trips to the U.S.S.R. where interviews with students, educators, and administrators were conducted. Further insight is provided from Levin’s experience as a school teacher in Moscow for five years before the outbreak of World War Two.

- Fitzpatrick, Sheila. Education and Social Mobility in the Soviet Union 1921-1934. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979.

One of the most comprehensive works on education in socialist Russia, Education and Social Mobility in the Soviet Union 1921-1934 by Sheila Fitzpatrick provides a wealth of knowledge on the changing educational system in Russia between 1917 and 1934. Her work covers a large spectrum from ideological changes in education to the salaries of educators. The book is structured in a chronological format to follow the new socialist Russian state as it develops and changes. Although a larger variety of topics are covered in her work, Sheila Fitzpatrick centers her writing on education as a means of social mobility in the newly created socialist society.

- Bereday, ed. The Changing Soviet School . Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1960.

The Changing Soviet School provides a wealth of information on education in Russia with chapters devoted to major phases of Russian history beginning with Tsarist Russia and concluding with the Soviet Union. The claims presented in the work are supported by the research of 70 American researchers who visited and toured soviet schools, universities, collective farms, and industrial plants in 1958. To provide complete research of the evolution of education in the U.S.S.R. the book presents education during Tsarist Russia, Revolutionary Russia, and the Soviet Union. The work is divided into three sections that all provide detailed insight into Russia education. Part one focuses on ideological, social, historical, and philosophical characteristics of Russian education to analyze pedagogy. Part two describes the formal institutions of preschool, primary school, secondary school, and university inquiring as to what content was taught, how content was taught, and how teachers were trained. Part three questions the universal nature of universal education by studying marginal groups like talented and handicapped students. The purpose of the work is twofold, first two provide a detailed image of the Soviet educational system and second to illuminate similarities between the Soviet system with the American educational system.

- Gorsuch, Anne E. Youth in Revolutionary Russia: Enthusiasts, Bohemians, Delinquents . Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2000.

Anne Gorsuch looks into the experiences of youth in Russia during the New Economic Policy. The economic challenges created by NEP left many children with no adult supervision when returning home from school. This situation caused largely by NEP resulted in limited many children to only four years of education before joining their parents in some form of work. Education for girls during this period was seen as too expensive so many parents kept daughters at home to work in the house and help raise younger children. Gorsuch provides insight into the role of gender in education for Russian youth for example, out of every one hundred days, males had 230 free hours and the females just 169.27. In addition to the role of gender in education she also provides important analysis of the influence of experimental forms of education. Entrance exams from secondary schools and universities demonstrated that students being taught at experimental schools were politically illiterate due to the ineffectiveness of the educators of these experimental institutions. These failures resulted in a relapse in curriculum from social behavior education to traditional history, economics, and political theory.

Scenes of Soviet Education from 1921:

Three communist Dutch school teachers went to Russia to observe the labor schools that had been created in the recently reformed Russia. They observed schools that taught toddlers up to adolescents. In these schools children were taught how to develop photographs, how to spin fabrics, how to use printing presses, how to work in a saw mill, and how to work in a laboratory. Each of the Dutch researchers wrote small biographies that can be found below. The observations of these three socialist educators serves as a gateway into the minds of socialist education.

Jan Cornelis Ceton

Jan Cornelis Ceton : Opposed book oriented education. Favored taking students for nature walks to embrace the world. He opposed Christian education as it only served as a means of maintaing the current social order. He saw no need for administration in education as it created authoritarian figures. In 1919 he co-founded the Communist Teachers Association. He published several works on new education in socialist journals such as The New Era, two of these works are listed below. Both of these works demonstrate Ceton’s desire to incorporate socialist values into the education system in Holland and later around the world.

Ceton, Jan Cornelis. “ Free school or compulsory state school” The New Era , (1902): 37-51, 109-121.

Ceton, Jan Cornelis. “Social Democracy and Education ” The New Era , (1913): 875 – 889.

Jan Cornelis Stam

Jan Cornelis Stam : Born in 1884 he grew up in a Calvinist family that placed heavy emphasis on education. He attended school at Sliedrecht, in South Holland where he was exposed to socialist values from some of his peers and teachers. He began teaching in 1903 and would later join the Social Democrat Party in 1909. He worked as an editor of the party newspaper The Tribune writing on socialist values in education and the neutral or co-ed school.

Wiliemse Willjbrecht

Willemse Wiljbrecht : A school teacher in Amsterdam from 1925 to 1940. Beginning in 1932 onward Willemse was a major figure in the creation and workings of the Marxist Worker Schools. She worked at Montessori Training for Teachers in Utrecht from 1940-1941. Willemse worked as the editor of Montessori Education from 1939 -1956. Many of her works were published in Renewal of Education and Montessori Education.

Wiljbrecht, Willemse. “ Our Children Will Be Our Judges ”

Below are scenes captured by Jan Cornelis Ceton, Jan Cornelis Stam, and Wilemse Willjbrecht during their travels to the Russia during 1921. These images expose the experimental nature of education during revolutionary Russia as students can be seen playing sports, acting in plays, and even chopping wood.

- Ceton, Jan. and Stam, Jan, and Wiljbrecht, Willemse. Soviet Education 1921. The International Institute of Social History. Accessed October 25, 2013.

Education During the Mid 20th Century Soviet Union

- Benton, William. Teachers and the Taught in the U.S.S.R. Kingsport: Kingsport Press, 1965.

Serving as a detailed analysis of Soviet education, William Benton’s Teachers and the Taught in the U.S.S.R covers specific areas such as film in education and the structuring of primary and secondary schools. Research from Benton’s 1964 trip to Moscow serves as the data for the majority of his book. The work uses a narrow lens in addressing Soviet education by focusing on particular areas and should be read as a supplement to works that take on the topic of Soviet education from a wider angle.

- Matthews, Mervyn. Education in the Soviet Union. London: University of Surrey, 1982.

Nikita Khrushchev

With the changing of leadership in the Soviet Union would come changes, some transitions would bring more change than others. In Education in the Soviet Union, Mervyn Matthews compares education under the administration of Nikita Khrushchev and Leonid Brezhnev. His comparison focuses on general education, technical schools, and higher education looking into characteristics like teachers’ attitudes, student well-being, and problems in administration. Much of this works looks into the societal shifts that occurred after Joseph Stalin’s death.

- Grant, Nigel. Soviet Education. New York: Penguin Books, 1979.

A brief overview of education in the U.S.S.R. during the 1960s can be found in Nigel Grant’s Soviet Education. In his work he aims to present the educational system of the Soviet Union using first hand accounts of students and professor from the U.S.S.R. to supplement statistical information, official documents, and scholarly journals. He presents the general characteristics of primary, secondary, and higher education covering ideology, structure, staffing of schools, and discipline. Grant draws connections to other educational systems from other nations in his description of the workings of Soviet education.

- Boston University

- Simon Rabinovitch

- Guided History

- History Department

- Education, Health, Transportation, Energy - Education

EDUCATION IN THE SOVIET ERA

The Soviet regime instituted a system of primary and secondary schooling and operated virtually all the schools in Russia. In 1959, only 36 percent of the population age 10 and over had a secondary education; by 1986 that figure had grown to 70 percent, and there were a half million people with doctorates or post-doctorates.

Education was highly centralized, and indoctrination in Marxist-Leninist theory was a major element of every school's curriculum. Schools were often showcase buildings. They often had large classrooms, a library and cafeteria. Some had museums. The Soviet system also maintained some traditions from tsarist times, such as the five-point grading scale, formal and regimented classroom environments, and standard school uniforms — dark dresses with white collars for girls, white shirts and black pants for boys. *

An effort was made to nurture students with special aptitudes and skills. Children with musical talent were directed into music schools with complete symphony orchestras. Those with sports skills and scientific aptitude were sent to Pioneer Palace sports and hobby complexes with Cosmonaut Rooms with devices that simulated space travel and hair driers in the girls locker room.

Teachers were fairly well paid and held in high esteem. They received good health care and were able to take long vacations on the Black Sea. Teachers were regarded as advocates of the Communist Party first and teachers of the subjects second. Students at teacher's college were required to take courses on Marxism-Leninism and Building Socialism.

Progress in developing the education system was mixed during the Brezhnev years. In the 1960s and 1970s, the percentage of working-age people with at least a secondary education steadily increased. Yet at the same time, access to higher education grew more limited. By 1980 the percentage of secondary-school graduates admitted to universities had dropped to only two-thirds of the 1960 figure. Students accepted into universities increasingly came from professional families rather than worker or peasant households. This trend toward the perpetuation of the educated elite was not only a function of the superior cultural background of elite families but also, in many cases, a result of their power to influence admissions procedures . [Source: Library of Congress, 1996*]

Goals and Failures of Soviet-Era Schools

The goal of education policy was to teach the masses how or read and write, and channel talented young people into science and technology. It was oriented more towards meeting the needs of society and the state rather than fostering individual development. Schools were free, compulsory, universal and classless and were used disseminate Communist doctrine as well as educate children. The set of ethics stressed the primacy of the collective over the interests of the individual. Therefore, for both teachers and students, creativity and individualism were discouraged.[Source: Library of Congress, July 1996 *]

As in other areas of Soviet life, the need for reform in education was felt in the 1980s. Reform programs in that period called for new curricula, textbooks, and teaching methods. The chief aim of those programs was to create a "new school" that would better equip Soviet citizens to deal with the modern, technologically advanced nation that Soviet leaders foresaw in the future. *

But schools and universities in the Soviet Union failed to supply adequately skilled labor to almost every sector of the economy, and overgrown bureaucracy further compromised education's contribution to society. At the same time, young Russians became increasingly cynical about the Marxist-Leninist philosophy they were forced to absorb, as well as the stifling of self-expression and individual responsibility. In the last years of the Soviet Union, funding was inadequate for the large-scale establishment of "new schools," and requirements of ideological purity continued to smother the new pedagogical creativity that was heralded in official pronouncements. *

Soviet-Era Schools

Compulsory education began at age seven and includes four years of elementary school and four years of middle school. After completing the eight grade students had the option of 1) dropping out and working; 2) attending a technical training school called a “technicum”; or 3) attending a two years of senior secondary school that prepared students for university.

Secondary school and university each lasted 3 or 4 years. Many schools ran six days a week and operated with morning shifts and afternoon shifts. Vocational schools were often attached to factories. Schools on collectives typically hade grades one through eight or one through ten.

Nursery schools and kindergartens served both as schools for the very young and day care centers. Many were operated factories or collective farms. People generally didn't have trouble finding kindergarten places for their kids. Nevertheless, by the 1980s the education infrastructure as a whole was in sorry shape. Facilities generally were inadequate, overcrowding was common, and equipment and materials were in short supply. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Because the Soviet Union had not built enough schools to accommodate increasing enrollment, Russia inherited a system of very large, overcrowded schools with a decaying infrastructure. By the late 1980s, 21 percent of students were attending schools with no central heating, and 30 percent were learning in buildings with no running water. *

Soviet-Era Schooling

According to the 1989 census, three-fifths of Russia's people aged fifteen and older had completed secondary school, and 8 percent had completed higher education. Wide variations in educational attainment exist between urban and rural areas. The 1989 census indicated that two-thirds of the country's urban population aged fifteen and older had finished secondary school, as compared with just under one-half of the rural population. [Source: Library of Congress, July 1996 *]

The underlying philosophy of Soviet schools was that the teacher's job was to transmit standardized materials to the students, and the student's job was to memorize those materials, all of which were put in the context of socialist ethics. One history teacher told the Washington Post that discipline was strict and Stalinism was a forbidden subject. “In my classes then, I never pronounced the words. ‘What do you think?’ You were supposed to learn and then answer exactly the way I told you.”

In the Soviet era teachers were fairly well paid and had high esteem. They received good health care and were able to take long vacations on the Black Sea. Students were often recruited for the month-long potato harvest in the fall. Many students tried to weasel out of it by inventing medical excuses.♪

Soviet-Era School Curriculum

In places were Russian was not the local language, instruction was in the local language and Russian was taught as a second language. In grade school, students were trained to pledge allegiance to the Communist Party.

Soviet Schools traditional emphasized rote learning over what the government wanted them to learn rather then helping them develop creative thinking skills. Discussions about morality and individual responsibility were strictly forbidden. The school curriculum was dictated by Moscow and filled with "mind numbing propaganda and cold Marxist logic." presented from a Leninist viewpoint. High school courses included "Economic Policies of Capitalism and Socialism” and "Dialectical Materialism."

The required reading list for high school students included books by Maxim Gorky, Alexander Fadayev’s “The Rout”, a tribute to Red soldiers who fought in the Russian civil war, and Imikhaul Sholokovs “Quiet Don”, a four-volume series about the Don Cossacks’ struggle for independence.

Propaganda and Education

In the Soviet Union, history textbooks asserted that people loved the state and left out details like pact made by Hitler and Stalin, East German students learned the Communists, not Jews, were the primary victims of the Holocaust; that the West German government was fascist succor to the Nazis, and that the United States was "the last and most decadent stage of capitalism" and a crime-ridden society full of drugs and racism.

"In those days, we were forced to believe everything we were told; you could never express any doubts," one student told the Washington Post. “It was real indoctrination. It created a lot of anger and suspicion in us when we learned that history was really different. Our parents seem astonished that we tend to question authority. But it only normal because we resented the lies we heard about in the past."

History was often defined as a triumph of Communism over the worst excesses of imperialism. One episode of American history that nearly every Russian student is familiar with is the "Great Barbecue,” when working class Americans rose up against industrial bourgeoisie and the remnants of feudal America.♪

Soviet-Era Universities

University education was free and students were given a stipend, which was sometimes increased with good grades. Training was highly specialized from the start. Students often spent five or six years studying their subjects and took only courses in their fields. Future doctors took only medical classes and future lawyers took only law classes. There was no such thing as a liberal arts curriculum.

The Soviet system dictated what classes university students would take and decided what jobs they would take after they graduated. The system encouraged students to go into pure and applied sciences, engineering, medicine and agriculture. About 50 percent of all students majored in engineering with hopes of getting a prestigious, well-rewarded join in a large state institution. The best and the brightest were often picked for scientific jobs with military applications.

The number of slots open in universities was determined by five-year plans which took into consideration the needs of certain region and the number of doctors, engineers and scientists the government decided country needed. The children of tradesmen and landowners from generations back were sometimes punished for their pedigree and had a harder time getting into good universities that those from peasant stock.

The Soviet university system produced good engineers and technicians. The humanities were highly ideologized. Soviet universities offered specialist programs. These were more specialized and different than the liberal arts and sciences curriculum offered at Western universities.

As part of a Soviet-era system called “raspedyelyeniye” ("assignment") students were told by the state where and what they should study and then they were assigned to a job. The system encouraged students to go into pure and applied sciences, engineering, medicine and agriculture. The best and the brightest were often picked for scientific jobs with military applications. About 50 percent of all students majored in engineering with hopes of getting a prestigious, well-rewarded join in a large state institution.

Young Pioneers

Young Pioneers is the youth branch of the Communist Party. All or nearly all children between the ages of 10 and 15 are required to join. They wear a red kerchief with their school uniform everyday, except when the weather is exceptionally hot and they wear a red pin instead. [Source: Eric Eckholm, New York Times, September 26, 1999]

The first Young Pioneers groups appeared in 1922 but the organization was not officially created until 1924. Eric Eckholm wrote in the New York Times, "Combining elements of the Scouts, the Safety Patrol and the Hall Monitor, larded with thick, simple doses of patriotism and Communism, the Young Pioneers remains a shared experience of children raised in Communist countries.

Young Pioneers are taught the proper way to dress, to raise the flag and salute their superiors. They read great Communist heroes and the good deeds performed by model Pioneers and learn to march in formation. Describing a Young Pioneer parade one Russian told the Washington Post, the ranks of children were “such a beautiful line of identical while blouses, a line of identical red pioneer ties and ribbons!”

The Young Pioneer organization sponsors after school hobby clubs and summer camps. In the Soviet Union there were several thousand Pioneer Palaces, that served as recreation centers, and several hundred Pioneer Camps, most of them associated with factories and official organizations. There were also Pioneer travel agencies and children-size model railroads. .

The clubs sponsored sports and arts activities and provided technical training. The were also classes in things like languages, chess, writing, dance, airplane building and art. Pioneer Camp were a summer ritual for Soviet youths. The activities were not all that different from those of American summer camps exception the instruction included Marxist economic and political philosophy.

Young Pioneer Initiation

Little Sparks are the Communist equivalent of cub scouts and brownies. At age nine they say a special pledge and go through a solemn rite of initiation, receiving their red scarves to become full fledged Young Pioneers.

Describing the ritual, Eric Eckholm wrote in the New York Times, "Lined up before an audience of classmates, teachers, and perhaps some beaming parents, the school band playing at the side, they stand at attention as sixth-graders march up and place red kerchiefs around heir necks. An older students leads them in the pledge."

The pledge goes: "I am a Young Pioneer. I pledge under the Young Pioneer flag that I am determined to follow the guidance of the Communist Party, to study hard, work hard and be ready to devote all my strength to he Communist cause."

Young Pioneer Organization

The pioneers are organized in school squads and troops under the supervision of their teachers, with the most studious, conscientious and kiss ass students acting as leaders. Most of the young pioneer leaders are members of the Communist Youth League. One young girl told the New York Times, "As a leader, I have to be a good student, get good grades and be willing to serve the other students. I feel that we have to study hard to build our country stronger."

The pioneers are evaluated on their performance in their activities, There are three tanks: Junior, Full and Senior Pioneers and punishments for those who don’t do what is expected of them.

When asked what happens when a Young Pioneer did something wrong, one former member told the New York Times, “They pull you out of this rank, put you in front of the other Pioneers and start scolding you . All the other kids stare at the one Pioneer in the middle, their eyes saying, ‘Shame on you.’ Imagine what this one person must feel, being alone face to fac with thus huge masse. A kid starts crying, ready to promise anything only to have a chance to get back to his place in the rank, to blend in and be the same as everybody else. For that he ready to give anything away.”

Image Sources:

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, U.S. government, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated May 2016

- Google+

Page Top

This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been authorized by the copyright owner. Such material is made available in an effort to advance understanding of country or topic discussed in the article. This constitutes 'fair use' of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. If you are the copyright owner and would like this content removed from factsanddetails.com, please contact me.

The Stalin Society

For the defence of stalin and the achievements of the soviet union, education in the soviet union, presentation made to the stalin society by ella rule.

The Soviet Union during the time that Stalin was General Secretary of the CPSU was a country at the lower stage of communism building itself up towards the higher stage. As is well known, at the lower stage of communism productive forces are not yet sufficiently developed to meet all the physical and cultural needs of the people, but the whole aim and purpose of this lower stage is to develop the productive forces so that these needs can be met at the earliest. It is precisely for these reasons that at the lower stage of communism workers are rewarded according to their labour. There is insufficient productivity to satisfy all needs so the higher stage of communism has to be delayed until this changes. The system of rewarding people according to the amount of work they do is quite good at encouraging hard work among people whose attitude to work has been scarred by years of working under capitalism and who regard work as nothing but drudgery rather than life’s prime want.

Article 121 of Soviet Constitution

Citizens of the USSR have the right to education. This right is ensured by universal and compulsory elementary education; by free education up to and including the 7th grade, by a system of state stipends for students of HE educational establishment who excel in their studies; by instruction in schools being conducted in the native language, an by the organisation in factories, state farms, MTSs, and collective farms of free vocational, technical and agronomic training for the working people.

But how exactly is a high level of productivity to be achieved, and when achieved, how is it to be maintained? Clearly a highly productive society must be equipped with all the latest technology. But in order to acquire that technology and then use it effectively, an educated population is necessary. Illiteracy must be eliminated. Hundreds upon thousands of Soviet experts must be trained.

At the start of this enterprise, the task is enormous, and the forces to tackle it are extremely meagre.. Education was a key factor, as is well explained by a petty-bourgeois English writer on education who studied the Soviet education system:

“The task of building from the ruins of the Russian Empire a modern, industrial, and socialist society has pushed on with a ruthlessness – and at a human cost – that is well known. But no measure of ruthless determination could in itself be enough; for the success of such projects as the FYPs [Five-year plans], the authorities depended on educational development no less than on the mustering of manpower and economic resources. There had to be a new force of engineers, scientists, technicians of all kinds … no possible source of talent could be left untapped, and the only way of meeting these needs was by the rapid development of a planned system of mass education.” (Grant, p.20 – see bibliography for detail).

In Tsarist Russia the education of the masses had been neither necessary or desirable as capitalism was little developed and did not need a literate working class, and education gives people expectations of a better life that Tsarist Russia could never satisfy. The result was that 73% of the population of Tsarist Russia (excluding children under 9) were illiterate. Only a quarter of all children ever went to school.

In Soviet Russia, by contrast, besides educating people for higher productivity Soviet education had also to prepare them to be good citizens in a communist society, encouraging them to let go of attitudes, towards work and possessions for instance, which capitalism had fostered and which many in the older generations still cling to. Grant writes that Soviet education is “designed not merely as a machine for the production of scientists, engineers, and technicians, but as an instrument of mass education from which the younger generation gain not only their formal learning, but their social, moral and political ideas as well.” (p.15).

Last, but not least, political understanding must be developed so that there is an enormous pool of workers with a high level of class consciousness to form the vanguard of the continuing class struggle. Grant writes: “… Soviet society … requires ‘political awareness’ in the mass of the population. This is more than mere conformity, which usually comes more easily through ignorance. Dumb acquiescence will not do; what is wanted is conformity versed in knowledge and study of political theory, conformity in the positive sense.” (p.23-24).

The question of education, then, is critical to the survival of communism and its development towards its higher stage. As Lenin said; “Without teaching there is no knowledge and without knowledge there is no communism.”

That is why during the period of the first two 5-year plans, when the Soviet people were straining to ensure their industrial productive capacity caught up with that of the most advanced imperialist countries, as they knew working-class state power in the USSR would be wiped out by imperialist military intervention if they did not succeed, huge resources were nevertheless poured into education – education of adults and of children. Between 1917 and 1937, 40 million adults were taught to read! The number of children and students in full-time education increased from 8 million in 1914 to 47 million in 1938-9. Secondary school attendance increased from under a million in 1914 to over 12 million in 1938-9. Numbers of university students increased from 112,000 in 1914 to 601,000 in 1938-9, and more schools were built in the USSR in 20 years than the Tsarist autocracy built in 200 years.

But besides providing education in schools, the Soviet Union also organised education for those in work. S. Sobolev (a member of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR and of the Supreme Soviet of RSFSR) wrote in Soviet Youth at Work and Play (in USSR Speaks for Itself pp.229-230)

“An extensive system of courses and study circles provides a wide range of educational facilities enabling them to become proficient in their particular trade or profession.”

“A system of vocational training schools attached directly to the factories has been functioning in the Soviet Union for more than 15 years. In these schools highly skilled workers from all branches of industry and the transport services are trained free of charge. The pupils in these schools acquire a general education equal to that provided in secondary schools, and under the supervision of qualified instructors, learn to become proficient in the trade they’ve selected…

“Since their foundation the vocational training schools have supplied the country with about 2 million skilled workers in various trades. Many of their graduates have since developed into master craftsmen, setting outstanding records of labour productivity.”

Besides secondary level education, there was also immense provision for workers to study for university degrees on a part-time (mostly correspondence course) basis but closely linked with the universities where students would be called to attend frequently special seminars or activities , much like the Open University in the UK today. This system was observed in operation by Grant in 1959. Part-time students accounted for 45% of total in 1959, (38% correspondence).

Nevertheless, providing education is one thing, but what about the quality of that education? Is it 3-R type education limited to enabling a worker to read the instructions for operating a machine and to have enough arithmetic to be able to measure materials adequately? Or is it education aimed at enabling workers to acquire a real understanding of nature and society? Is it the oppressive rote learning of a vast amount of apparently irrelevant facts, or is it the acquisition of genuine competence in the face of the complex situations that the world presents to humanity? Is it the inculcation of propaganda designed to enslave, or is it the passport to freedom via appreciation of necessity?