Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

TECLA: A temperament and psychological type prediction framework from Twitter data

Contributed equally to this work with: Ana Carolina E. S. Lima, Leandro Nunes de Castro

Roles Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Natural Computing and Machine Learning Laboratory, Mackenzie Presbyterian University, São Paulo, Brazil

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing

- Ana Carolina E. S. Lima,

- Leandro Nunes de Castro

- Published: March 12, 2019

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0212844

- Reader Comments

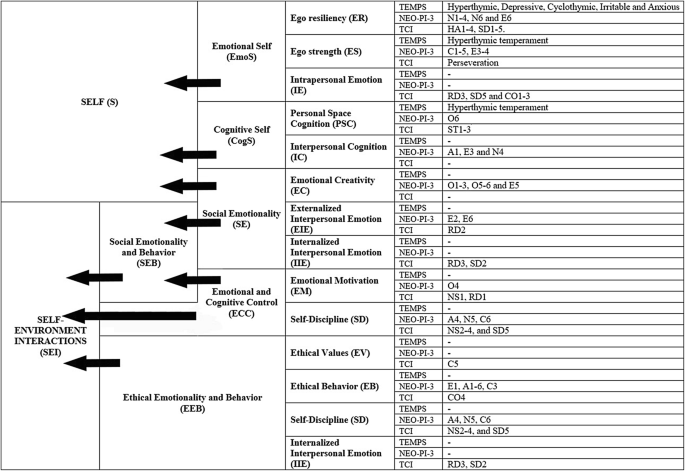

Temperament and Psychological Types can be defined as innate psychological characteristics associated with how we relate with the world, and often influence our study and career choices. Furthermore, understanding these features help us manage conflicts, develop leadership, improve teaching and many other skills. Assigning temperament and psychological types is usually made by filling specific questionnaires. However, it is possible to identify temperamental characteristics from a linguistic and behavioral analysis of social media data from a user. Thus, machine-learning algorithms can be used to learn from a user’s social media data and infer his/her behavioral type. This paper initially provides a brief historical review of theories on temperament and then brings a survey of research aimed at predicting temperament and psychological types from social media data. It follows with the proposal of a framework to predict temperament and psychological types from a linguistic and behavioral analysis of Twitter data. The proposed framework infers temperament types following the David Keirsey’s model, and psychological types based on the MBTI model. Various data modelling and classifiers are used. The results showed that Random Forests with the LIWC technique can predict with 96.46% of accuracy the Artisan temperament, 92.19% the Guardian temperament, 78.68% the Idealist, and 83.82% the Rational temperament. The MBTI results also showed that Random Forests achieved a better performance with an accuracy of 82.05% for the E/I pair, 88.38% for the S/N pair, 80.57% for the T/F pair, and 78.26% for the J/P pair.

Citation: Lima ACES, de Castro LN (2019) TECLA: A temperament and psychological type prediction framework from Twitter data. PLoS ONE 14(3): e0212844. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0212844

Editor: King-wa Fu, The University of Hong Kong, HONG KONG

Received: May 10, 2018; Accepted: February 12, 2019; Published: March 12, 2019

Copyright: © 2019 Lima, de Castro. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: Data underlying the study is third-party data belonging to the authors of the "Personality Traits on Twitter—or—How to Get 1,500 Personality Tests in a Week". This data is available from https://bitbucket.org/bplank/wassa2015 . The authors of the present study confirm that they did not have any special access to this data that others would not have.

Funding: This work was supported by Mackenzie Presbyterian University, Mackpesquisa, CNPq, and Capes to ACESL as well as FAPESP. Intel also supported this research as an Artificial Intelligence Center of Excellence. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: Intel supported this research as an Artificial Intelligence Center of Excellence. This does not alter our adherence to PLOS ONE policies on sharing data and materials.

Introduction

The study of psychological types or temperament lead us to the understanding of how a person relates with the world, either by the choices he makes or the way he absorbs information. For a long time, this theme has been researched and associated with well-being, lifestyle, employment, leadership, study, etc. One way of knowing a person’s psychological type is by submitting him to questionnaires about his habits and choices, for example the MBTI (Myers-Briggs Type Indicator), which returns the psychological type of a person and is based on the studies of Jung and Myers-Briggs, and the Keirsey Temperament Sorter (KTS), which returns a profile associated with the temperament taxonomy created by David Keirsey.

In general, such forms involve many questions and can be biased by the environment in which the respondent is. One way to balance this bias would be to extract information in a passive way, for example, in the interactions (posts, likes, etc.) within social media, a service increasingly present in our daily lives. Social media can be seen as repositories of actions, behaviors and preferences that can be mapped onto psychological features. This occurs due to a user-free content creation, where each person has a role in creating and sharing content [ 1 ]. Wiszniewski and Coyne [ 2 ] argue that whenever an individual interacts in a social sphere he paints before himself a mask of his identity that becomes even more pronounced as the individual needs to fill in a profile.

The goal of this research is to identify if there are behavioral patterns in the information shared in social media that can be mapped with high precision into the psychological types of the MBTI or the temperaments of Keirsey. This is, therefore, an exploratory paper on the ability of traditional text mining techniques and natural language processing to assist in the extraction and classification of patterns. From our literature review we expand the combinations of text pre-processing techniques and classification algorithms in relation to the papers presented here. We also mapped a database of MBTI results in the Artisan, Guardian, Idealist and Rational types in order to demonstrate the applicability also in the concept of temperament proposed by David Keirsey. In terms of application, it is useful for the preparation of marketing campaigns, more accurate hiring and promotion processes, turnover reduction, improvement of working environment quality, and many other applications related to human capital recruitment, selection and maintenance.

The combination of human behavior research and text/data mining techniques provides insights about the virtual persona, such as his/her influence on others [ 3 , 4 ], how much they trust one another [ 5 , 6 ], their life satisfaction [ 7 ], personality [ 8 , 1 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 ], emotions [ 13 , 14 ], political preferences [ 15 , 16 ], emotion and mood state [ 17 , 18 ], depression [ 19 , 20 ], disorders [ 21 , 22 ], among many others.

The goal of automating the prediction of temperament and psychological type is not to replace the use of tests already validated, but, instead, to provide a new tool based on a completely different and passive data to support specialists. More specifically, this research will be based on Twitter data as case study, mainly due to its flexibility in providing open data for collection and analysis. This paper presents a series of classifiers evaluations to map the behavior of social media users, based on their Twitter posts, in relation to the temperament and psychological type and summarize the methodology in a structure called Temperament Classification Framework (TECLA).

To assess the performance of the proposed framework we used a dataset from the literature containing over a million tweets from 1,500 users. Five classification algorithms were evaluated: Naïve Bayes (NB); Support Vector Machines (SVM); Decision Tree (J48); Multilayer Perceptron (MLP); and K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN). We compare these algorithms with Twitter features and three text representation schemes (MRC, LIWC, Apache OpenNLP) to find a suitable combination to determine the temperament and psychological types based on Twitter messages.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides a brief historical perspective on temperament theories, emphasizing the models proposed by Myers-Briggs and later Keirsey. Section 3 brings a brief review of the works in the literature dealing with the automatic classification of temperament and psychological types. The Temperament Classification Framework (TECLA) is presented in Section 4, and its performance is analyzed in Section 5. The paper is concluded in Section 6 with a general discussion and perspectives for future research.

A Brief historical perspective on temperament theories

Temperament characterizes a set of mental tendencies related to the way someone perceives, analyzes and makes daily decisions [ 23 ]. It represents the uniqueness and intensity of psychic affects and the dominant structure of mood and motivation in each individual. It is a form of reaction and sensitivity of a person to the world, which is revealed by his/her attitudes and behaviors, thus composing his/her organic basis [ 24 ]. This set of trends is innate, that is, it appears from birth, and is closely linked to biological or physiological determinants, which therefore change relatively little with development [ 25 ]. It can change and weakens throughout life, but it is never eliminated [ 24 ]. In the present research, temperament is defined as a set of innate and hereditary tendencies , responsible for how one perceives and interacts with the world .

The literature is filled with different terminologies to refer to temperament, based on the authors’ view of such characteristics. For instance, Hippocrates called it the four humors, Carl Jung, Isabel Myers Briggs and Katharine Cook Briggs called it psychological types, and Carlos Galeno and David Keirsey, called it temperament [ 25 , 26 , 27 ]. We summarize the temperament as a concept that converges to a set of innate characteristics of an individual, closely linked to biological or physiological determinants, which change relatively little during the personal development [ 25 ].

We adopted the temperament model proposed by David Keirsey [ 27 ] and the psychological types introduced by Myers and Briggs [ 28 ]. Keirsey’s model maps temperament into four types: artisan; guardian; idealist; and rational. This model is widely accepted for the understanding of professional trends, thus being potentially applicable in recruitment and selection processes, promising areas for social media data analysis. The Myers and Briggs’ model has a set of 16 psychological types that were investigated and defined from the studies of Carl Jung on the psychological types.

Carl Gustav Jung proposed one of the most comprehensive and well-known temperament typologies in his book Psychological Types [ 29 ]. Jung analyzed the temperament according to the workings of the mind. For him the mind is composed of an association between attitudes and functions . The attitudes ( extroversion (E) and introversion (I)) would be the source of psychic energy and the functions correspond to the way each individual acquires and processes information. Jung related four functions, two referring to obtaining information: sensation (S) and intuition (N); and two for decision-making: thought (T) and feeling (F) [ 25 ]. Then, Isabel Myers and Katheryn Myers Briggs added a new pair of functions: judgment (J) and perception (P), which assess whether an individual’s orientation to the outside world comes from a rational ( judging ) or irrational ( perceiving ) function.

D. Keirsey [ 27 ] focused his research on the parallel between the Myers-Briggs taxonomy and the observation of temperament in action at the time of choices, behavior patterns, logic and consistency. He assumed that the temperament associated with character forms the personality of the individual; the temperament being innate and the character emergent, developed by the interaction of temperament with the environment. Thus, the types are driven by aspirations and interests, which is what motivates us to live, act, move and play a role in society [ 27 ]. He noted that the interests and aspirations are more related to the perception (S-N), totally instinctive, more than to decision-making (T-F), which is fully rational. The sensation (S) can combine with judgment (J) or perception (P), while intuition (N) with feeling (F) or thinking (T). This observation resulted in four temperament types: Guardian (SJ); Artisan (SP); Idealist (NF); and Rational (NT) [ 23 , 27 ].

Although the characteristics of Myers-Briggs model is binary (dichotomic), there are studies that suggest that a better representation would be continuous with degrees of belonging to each function and attitude [ 30 , 31 , 32 ]. The inventory provided by Myers and Briggs aims to determine which of two functions or attitudes is preferred. The score indicates the tendency in the dichotomy. Results with low scores suggest a tension between the opposite pairs rather than an indication of equal preference. However, the tension is unclear whether the equal represents strength in both pair, equal weakness in both areas, or equal neutrality in both areas [ 33 ]. We have adopted the binary standard due to our methodology for acquiring a dataset since the disclosure of the MBTI result by a social media user occurs through the label (ENTJ, INFP, etc.), without direct association with the score in each pair.

Automatic temperament classification: A literature review

Understanding social media users involves the analysis of their behaviors and interactions in social media, like their followers, mentions, messages, friends, photos, videos and comments. Understanding the users means being able to quantify and qualify how they present themselves [ 34 ]. The automatic recognition of temperament by means of computational techniques can help many business sectors and social researchers in understanding social media users. To date, there are only a few works related to the automatic temperament/psychological types classification in the literature, that is, Keirsey and MBTI labels. The main reason for the scarcity of works in this area is the difficulty in finding data for training classifiers. This section provides a review of the specific works found in the literature related with these two topics. Although there are many other works addressing the prediction of user characteristics from social media data, these are out of the scope of the present paper.

Luyckx and Daelemans [ 35 ] created a 200,000-word Personae corpus consisting of 145 undergraduate student essays about an Artificial Life documentary written in Dutch. Besides, the students submitted their MBTI profile. In this work, the authors performed an authorship attribution and personality prediction. The Memory-Based Shallow Parser (MBSP), n-gram and Lexical features were used to extract the text features. For personality prediction, a 10-fold cross-validation training was performed with a method based on the K-NN algorithm, called TiMBL (Memory-based learning). The experiments contained 84 binary classification tasks, each one for the MBTI dichotomy. The authors concluded that the prediction of introverted-extraverted and intuitive-sensing were fairly accurate, with average F-measures of 65.38% and 61.81%, respectively.

Komisin and Guinn [ 36 ] developed a system based on the classification of documents to determine the psychological type according to Myers-Briggs model. In their experiments, they used a Naïve Bayes classifier and Support Vector Machines. Data were collected as part of a postgraduate course in conflict management offered to undergraduate students, in which students performed the MBTI and Best Possible Future Self (BPFS) tests. The BPFS contains self-descriptive elements, in present and future, in different contexts (e.g., work, school, family, finances). Data were collected over three semesters between 2010 and 2011. The n-gram and Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC) were used to provide a representation of texts. The authors concluded that the dichotomies Thinking/Feeling (T/F) were predicted with over 75% accuracy for the precision and recall measures using Naïve Bayes with leave-one-out cross validation. For the Intuitive/Sensing (N/S) dichotomy, the LIWC features resulted in less successful predictions. Introversion/Extroversion (I/E) and Judgement/Perception (J/P) did not achieve good precision and recall results.

Brinks and White [ 37 ] used various algorithms to detect the Myers-Briggs temperament types in tweets. The aim of the project was to develop a computer system capable of performing the function of the human analyst trained to apply the MBTI based on textual communication. The authors argued that although the results of the MBTI are confidential, many individuals openly reveal their type in a variety of ways and media, including Twitter. They showed that, in a search on Twitter with the term “#INFP” messages were found such as: “I just reread the Myers-Briggs description of my #INFP personality type. It’s scary accurate”. Thus, the data were collected from users that revealed their temperament profiles. 6,358 Twitter users were observed and it were collected two hundred tweets from each. In total, it was analyzed 960,715 tweets. On average, classifiers achieved a precision of 66.25%.

Plank and Hovy [ 38 ] collected 1.2 million tweets classified according to the Myers-Briggs system. For these, the authors monitored messages that mentioned any of the 16 types associated with the words Briggs or Myers. Thus, they obtained 1,500 different users, and collected between 100 and 2,000 of their latest tweets, resulting in a corpus of 1.2 million tweets. The authors structured the messages using n -grams, in addition to the genre information, tweets count, number of followers, number of followings, among other service features. One goal was to find out which attributes would be more characteristic in each dimension of the Myers-Briggs model. They used logistic regression to analyze the attributes in each dimension and concluded that the data can provide enough linguistic evidence to predict the dimensions reliably: Introversion/Extroversion and Feeling/Thinking.

Verhoeven et al [ 39 ] created a MBTI dataset in six languages (Dutch, German, French, Italian, Portuguese and Spanish) with 18.168 users and approximately 34 million tweets in total distributed among the languages. They used the same methodology presented in [ 38 ] to collect the data. After the construction of the database, the authors performed classification tests to predict both gender and Myers-Briggs personality dimensions (I/E, N/S, T/F and J/P). For the experiments the authors used 200 tweets per user and discarded those who had fewer than 200 messages. The authors used LinearSVC with standard parameters with n -grams. The classification was performed using 10-fold cross-validation. Considering all languages, the average F-measure for the I/E dimension was 67.87%, 73.01% for the N/S dimension, 58.45% for the T/F dimension, and 56.06% for the J/P dimension.

Lukito et al. [ 40 ] used Twitter as data source in Indonesia to predict personality and performed an MBTI psychological test with a user base of 97 people. Approximately 240,000 tweets were collected, an average of 2,500 tweets per Twitter user. They selected 15 users for testing and changed the training set size according to the experiment. The classification algorithm used was Naïve Bayes and the messages were structured by n -gram and POS-tag. The best result was achieved for the I/E dichotomy with 80% accuracy, the other dichotomies had the same 60% accuracy levels. The authors compared their results with the work proposed by [ 38 ], concluding that their proposal was superior for the pairs I/E and J/P, being the latter one of the most difficult to predict.

Lima & de Castro [ 1 ] developed a framework called TECLA to predict temperament types (Artisan, Guardian, Idealist, and Rational). The dataset with approximately 29.200 tweets was collected from Twitter. They used LIWC text representation and Twitter user’s account information (like tweets count, number of followers, and number of followings). The authors used NB, KNN, SVM and Decision Tree algorithms to evaluate the proposal. The best accuracy results were in Artisan and Guardian with 87.67% and 83.56%, respectively. The accuracy did not exceed 60.27% for the Idealist temperament and 58.90% for Rational.

Table 1 shows a summary of the papers found, detaching the classification algorithms, main features and performance measures used. It also presents the best results obtained based on the measures adopted. The results of [ 37 , 38 , 40 ], all based on tweets, suggest a higher predisposition for I/E and N/S pairs. The F-measure in [ 36 ] was obtained from the Precision and Recall.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0212844.t001

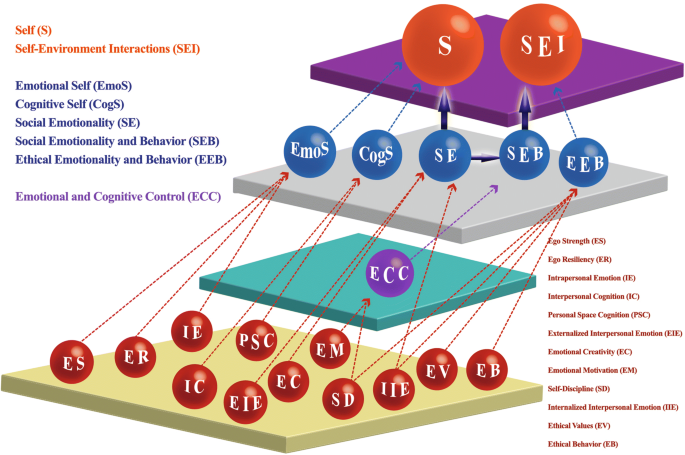

TECLA: The temperament classification framework

The Te mperament Cla ssification Framework (TECLA) was developed as an outcome of the use of text mining and natural language processing techniques to classify the temperament or psychological type of social media users. The goal is to provide a modular structure that allows us to use and evaluate different techniques quickly and intuitively. Furthermore, it follows the main steps of KDD ( Knowledge Discovery in Databases ) [ 41 ]. Hence, the TECLA has the following modules: data acquisition module ; message preprocessing module ; temperament classification module ; and evaluation module . Each one of them will be detailed in the following.

Data acquisition module

The data acquisition module is responsible for monitoring and receiving information from the users to be classified. For example, in the case of Twitter, it is necessary to obtain usage information, such as number of tweets, number of followers and followed, plus a set of tweets.

Message pre-processing module

The TECLA framework does not work directly with the tweets, but uses information extracted from them, called meta-attributes. Such information can be divided into two categories: grammatical and behavioral. The behavioral category extracts information about the social media use and is specific to each type of media. In the case of Twitter, it includes the number of tweets, number of followers, followed, favorites, number of listings and number of times the user was favorited. The grammar category considers information from LIWC [ 42 , 43 ], MRC [ 44 ], sTagger [ 45 ], or oNLP [ 46 ], extracted from the user’s set of messages, similarly to what was proposed in the Polarity Analysis Framework introduced by the authors [ 14 ]. Therefore, the message pre-processing module is responsible for extracting meta-attributes from the data (usage and message corpus) and building a new base, called meta-base, from the extracted meta-attributes. The list of meta-attributes used in TECLA is summarized in Table 2 .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0212844.t002

Temperament classification module

The temperament classification module infers a temperament from the characteristics (meta-attributes) extracted in the previous module. In principle, this module is based on the application of a specific algorithm and can incorporate any kind of classifier. For the classification of the MBTI model, the system was designed with four classifiers ( Fig 1 ) that receive the same data, but is trained to identify the opposing pairs of attitudes and functions. A classifier is trained and responsible for defining the attitude (Extroversion/Introversion—E/I) and the others the functions (Intuition/Sensation—N/S, Thinking/Feeling—T/F, Judgment/Perception—J/P), all trained in isolation. These classifiers were called decomposing classifiers .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0212844.g001

Each of these classifiers is binary, so the answer is either Extroversion or Introversion, Intuition or Sensation, Thought or Feeling, Judgment or Perception. After training, the response of the four classifiers will define the psychological type, e.g., ISTJ or ENFP (Section 2). Therefore, the psychological type of each user was split into four binary classes. The user may be extroverted or introverted, intuitive or sensory, thinker or sentimental, and judgmental or perceptive, as illustrated in Fig 2 .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0212844.g002

For the classification based on the Keirsey model a sequence of classifiers was constructed. As pointed out in [ 47 ] one of the strategies to work with multiclass classifiers is the combination of classifiers generated in binary subproblems. With this, there is a decomposition of the problem into binary problems. Separating the problem into binary classifiers can reduce the computational complexity involved in solving the total problem with simpler subtasks. In this case, the classifier has the same scheme shown in Fig 1 , however, the first classifier that returns the result “1” will determine the class of the object, as illustrated in Fig 3 .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0212844.g003

Evaluation module

In order to measure the TECLA performance, it was used the accuracy, F-measure, which involves precision and recall, and the area under the ROC curve (AUC). Accuracy is the number of objects correctly classified over the sum of all objects. The F-measure represents the harmonic mean between precision and recall, where precision is the percentage of a class correctly classified and recall is the number of objects correctly classified over the total number of objects that really belong to that class [ 48 , 49 ]

Performance assessment

The goal of this study is to design a temperament predictor that can infer the temperament of a certain individual (social media user) based on what he writes in the social media, instead of applying him a specific temperament test. This is a very interesting and promising approach, because it allows one to know someone’s temperament in spontaneous situations. To assess the performance of TECLA we used a recent, public dataset with over one million tweets.

Data acquisition

The database used comes from the [ 38 ] paper, in which the Twitter users are classified according to the psychological types of Myers-Briggs. The dataset contains 1.2 million tweets from 1,500 users. The number of tweets varies from one user to another. To be part of the database a user needs to have at least 100 tweets and we downloaded at most 2,000 tweets per user. The attributes available and useful are: MBTI; gender; number of followers; number of tweets; number of favorites; and number of listings. Table 3 shows the user distribution for each psychological type of the Myers-Briggs taxonomy. Although considered rare, the intuitive types, especially the INFP and INTJ, were the most common types within the collected database. By contrast, the sensory types (ESFJ, ESTJ, ESFP, ESTP, ISFP, ISTP, ISFJ and ISTJ) accounted for only about 21% of the data.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0212844.t003

The ratio between each element of the E/I, N/S, T/F, and J/P pairs can be seen in Table 4 . There is a clear imbalance between the N/S pair, which may reflect the classification results. However, for this study, no class balancing was performed because it would imply a reduction in the number of users in other pairs.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0212844.t004

To evaluate the Keirsey model, each MBTI type was mapped into its model (Artisan, Guardian, Idealist and Rational). Table 5 describes the number of users by temperament. The Artisan and Guardian classes have the smallest number of users, because of the predominance of intuitive in the database (Idealists and Rational).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0212844.t005

Pre-processing

The attributes provided by the Plank dataset are called behavior attributes, in reference to the behavior of users in the microblog. Table 6 shows the average value of the behavior attributes for each temperament (followers, statuses, favorites, listed and gender). In all temperaments/psychological types the predominant gender was female. In the N/S pair we emphasize the fact that the sensorial ones have, on average, more followers and tweet more frequently, although this is the function with fewer representatives in the database (only 22.53%). The difference between Guardians and Artisans, both sensory, is greater in relation to the number of followers and listed count. On the other hand, among the intuitive there is a greater balance in the way of using the microblog.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0212844.t006

Experimental results

All tests were performed with 10 runs of a k -fold cross-validation ( k = 5). First the results will be presented for the Keirsey model, then the MBTI model. In both cases, it is expected to show the ability of the classifiers to infer each of the classes, that is, if from the input data it is possible to identify an Artisan, Guardian, Idealist or Rational person, or, based on the MBTI model the pairs E/I, N/S, T/F, J/P. In all cases the measures adopted to evaluate the classifiers were the accuracy per class ( percentage of correct classification per class , ACC ), the F-measure ( F ), which is the harmonic mean between Precision and Recall , as discussed previously, and the area under the curve (AUC). The AUC is a summary of the ROC curve (sensitivity versus specificity), and high levels in AUC indicate that, on average, the true positive rate is higher than the false positive rate. The following classifiers were evaluated: AdaBoost; Bagging; J48; Naïve Bayes; Random Forest; and SVM. All classifiers used are from the Python library Scikit-learn 0.19.1 with default settings. We used a workstation with an Intel Core i5-3210M @ 3,10 GHz, 3 MB smart cache, quad-core on hyper-threading, 6 GB RAM memory, 904 GB HD @ 5400 RPM and Windows 8.1 operation system.

Results for the keirsey model.

The following tables show the test results for the Keirsey model: Artisan; Guardian; Idealist; and Rational. The goal is to answer the following question: “ Is it possible to infer the user’s temperament based on his posts ?”. Our tests began with an attribute analysis to understand the best possible configuration. We performed a ranking of the importance of the attributes based on the information gain to perform attribute selection tests and analyze the best results by observing the accuracy and F-measure. Note that our technique separates binary classifiers for each temperament, so the results are divided into ACC, F-measure for class 0 ("No", which means does not have the temperament), F-measure for class 1 ("Yes", which means has the temperament), and AUC of positive result (“Yes”).

Our first analysis refers only to the Twitter attributes and Table 7 below summarizes these results. It is possible to note that, in general, there is a tendency for the classifiers to choose the "No" class, which is the predominant class. Thus, the F-measure for the "Yes" is low. By comparing the ACC and AUC the best result was achieved with the Random Forest using the 5 attributes (total number of tweets posted by the user so far, number of followers, number of followed, number of times the user was listed, and number of times the user was favorited).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0212844.t007

We proceeded testing in scenarios in which the Twitter attributes would not be available, but only the text of tweets. For this case, we have tested three text structuring techniques separately, as mentioned in the pre-processing section: MRC, LIWC and oNLP. Note that the performance had the same behavior of the previous evaluation with a low F-measure for the "Yes" class, indicating the trend in the classifiers for one of the classes. Table 8 presents the best performance with 9 attributes with the Random Forest (87.48%±0.25%) and Bagging (83.23%±0.42%) algorithms. The combination SVM + MRC Features was not successful, because the algorithm could not identify patterns for the class Yes (0.00±0.00%).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0212844.t008

The LIWC showed a better performance, which could be noticed in the AUC measure. By analyzing the results we observed that the Random Forest performance is usually superior; the best accuracy was 87.99%±0.29% with 25 attributes ( Table 9 ). In general, there was no significant change in accuracy and the choice for these attributes was due to the F-measure (Yes). However, there was substantial improvement in the AUC value. Thus, the best performance was obtained by the Random Forest with 25 attributes: 91.14%±0.13% for the F-measure (No); and 70.52%±0.81% for the F-measure (Yes).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0212844.t009

Similarly to the Twitter and MRC results for oNLP, Bagging and Random Forest (also J48) achieved an AUC above 70%, indicating a better identification of “Yes”. By observing the other measures, again the Random Forest algorithm had the best performance with the oNLP 24 attributes ( Table 10 ). Therefore, the average accuracy was 87.60%±0.33%, the average F-measure (No) was 90.95%±0.31%, the average F-measure (Yes) was 69.68%±0.63% and AUC was 86.12%±0.76%.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0212844.t010

Based on its superior performance for all text representation mechanisms, Table 11 details the results of the Random Forest algorithm. By observing the different text representations, the best classification result occurred in the Artisan temperament with 96.46%±0.27% of accuracy for LIWC (25 attributes). These results suggest that the system can be more precise to find what is not Artisan, with all features with an average F-measure of 97.60%±0.24% for Twitter, 98.09%±0.22% for MRC, 98.11%±0.14% for LIWC and 98.08%±0.13% for oNLP. This can also be observed for the Guardian with F-measure (No) of 94.66%±0.30% for Twitter, 95.42%±0.24% for MRC, 95.61%±0.24% for LIWC and 95.51%±0.25% for oNLP. For the idealist the classifier was able to better discriminate the two classes. In the best scenario (LIWC 25 features) the F-measure (No) was 81.47%±0.50% and F-measure (Yes) 74.89%±0.87%. The AUC measure remained constant in all temperament types, around 80%, indicating a low false positive rate.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0212844.t011

Results for the MBTI Model.

The second set of results presented here are for the decomposed classifiers for the MBTI model. Each classifier is responsible for one of the MBTI pairs. In all cases, the same classification algorithm will be run for all classifiers. The goal is to answer the following question: Is it possible to identify the user's psychological attitudes and functions based on what he/she writes in social media ? If it is possible, then a deeper understanding of the virtual persona can be achieved by analyzing social media data. As our previous analysis with the Keirsey model prediction, we also performed an attribute analysis for the MBTI model prediction. Table 12 summarizes the results of the Twitter attributes’ evaluation. Both F-measure (No) and F-measure (Yes) have a value less than 70%, except for Bagging (71.97%±0.34%) and Random Forest (79.29%±0.23%) with 5 attributes, that is, with all the original attributes of the dataset. Both algorithms also achieved high AUC values indicating a good performance for the positive class.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0212844.t012

For the MRC attributes ( Table 13 ), we observed a better performance with 16 attributes. As in the Twitter case attributes, the Bagging and Random Forest algorithms also had a better performance, mainly when we compare the AUC, 81.26±0.46 for Bagging and 87.06±0.25 for the Random Forest. Also, the F-measure, 70.02%±1.15% / 74.46%±0.49% for Bagging and 78.80%±0.62% / 79.13%±0.37% for the Random Forrest. In general, as in the Twitter attributes, the performance of the classifiers was higher when compared with the Keirsey model classification in relation to the F-measure balance.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0212844.t013

The results for the LIWC attributes analysis, presented in Table 14 , show a better performance (AUC) for 24–28 attributes with the best result for 27 attributes associated with the Bagging (82.85±0.43), J48 (77.04±0.43) and Random Forest (87.79±0.56) algorithms. This suggests that the LIWC attributes may better characterize the problem when compared with the previous results also for the Naïve Bayes, AdaBoost and SVM.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0212844.t014

As with LIWC, the oNLP ( Table 15 ) results were satisfactory for Bagging, J48 and Random Forest, mainly for 22 attributes. The highest accuracy was 82.15%±0.14% for the Random Forrest. The Naïve Bayes classifier had the worst accuracy level with only 60.69%±0.13%. AdaBoost and SVM achieved, respectively, 65.02%±0.16% and 64.75%±0.15% of accuracy. Comparing the AUC results, the SVM had the worst performance.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0212844.t015

Table 16 details the Random Forest algorithm results due to its overall superior performance. For the studied database it was possible to predict the E/I pair with a mean average accuracy of 82.05%±0.65% for the oNLP features. The F-measure (No) indicates the first letter in the pair. In the E/I case, the Random Forest with oNLP features had an F-measure for Extroversion of 87.12%±0.44% and 70.38%±1.26% for Introversion. The pair S/N achieved 88.38%±0.68% of accuracy also with oNLP. The F-measure for N (intuition) was 92.66%±0.41% and 72.13%±1.94% for S (Sensation). In T/F the accuracy was 80.57%±0.80% for LIWC with 27 attributes, 84.49%±0.63% of F-measure to F (Feeling) and 74.01%±1.15% of T (Thinking) F-measure. The pair J/P had the lowest accuracy of 78.26%±0.79% (LIWC with 27 attributes). The precision was better in J (Judging) with 81.49%±0.66% of F-measure. Like the Keirsey type prediction, the AUC indicates a good performance of true positive in relation to false positive rate.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0212844.t016

Comparing with results from the literature

Finally, in Table 17 we compare our Keirsey and MBTI results with the literature. By analyzing the results from [ 38 ] our performance was superior for all MBTI pairs. We have also been more effective in the I/E and N/S pairs, however the use of Random Forest combined with other forms of text representation has promoted better performance for T/F and J/P pairs. For the classification results of Keirsey temperaments we compared with previous results obtained in the first steps to build this tool. In this case, we have also achieved an increase in performance. The F-measure in [ 36 ] was obtained from the Precision and Recall.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0212844.t017

Discussion and future trends

The purpose of this paper was threefold: to provide a brief historical review on temperament theories; to make a brief survey of machine-learning research on temperament and psychological type prediction; and to investigate the temperament and psychological types prediction based on data produced by social media users. In this latter contribution, the hypothesis this work tries to validate is if it is possible to predict the virtual persona temperament without using a questionnaire, that is, to use artificial intelligence techniques to understand and classify the profile of users based on what they share and how they behave in social media. The importance of this tool lies in trying to lessen a possible bias provided by questionnaires, when a user knows he is being explicitly evaluated.

From the literature review we seek to extend our previous results [ 14 ], both on text processing techniques and algorithms for building predictive models. With this, we present a set of results based on the combination of different text structuring techniques and classification algorithms. Derived from the proposals presented by [ 37 ] and [ 38 ], on Twitter data, we aim to identify the ability of the models to estimate the temperament typology proposed in [ 27 ].

User analysis was performed using the database provided in [ 38 ], composed of MBTI results and transformed into the Keirsey model, thus performing classification tests for both models. The results pointed to the use of Random Forests with LIWC structuring for the Keirsey model (96.46% of accuracy for Artisan, 92.19% of accuracy for Guardian, 78.68% of accuracy for Idealist, 83.82% of accuracy for Rational), and LIWC or oNLP for the MBTI (82.05% accuracy for E/I pair, 88.38% accuracy for S/N pair, 80.57% accuracy for T/F pair and 78.26% accuracy for J/P pair).

We believe in the importance of understanding the behavior of users on social media, and we also believe that information such as psychological types can help in this regard. This information can serve as input to many profiling systems in various areas. Here, we did an exploratory study aimed at understanding the potential of machine learning techniques for temperament identification. We would like to expand this research to new databases both from Twitter and other social media in order to explore the framework potential. We would also like to present case studies applying TECLA to different groups of users, and thus answer questions such as: What are the profiles of people who talk about the same subject? What is the profile of people who watch a TV show, movie or series? What is the profile of people who consume a specific product or service?

Finally, further research will also assess the computational scalability of TECLA when using High Performance Computing (HPC) platforms. We performed some preliminary experiments in this direction with one of the best scenarios obtained in this paper (i.e., Random Forest for the Keirsey model and Twitter 5 features) using an Intel Xeon Platinum 8160 processor @ 2.10 GHz, each one with 24 physical cores (48 logical) and 33 MB of cache memory, 190 GB of RAM and obtained a significant gain in performance. As social media data arrives continually, a comprehensive set of experiments will be performed to assess the scalability of TECLA in HPC platforms.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Mackenzie Presbyterian University, Mackpesquisa, CNPq, and Capes to ACESL as well as FAPESP. Intel also supported this research as an Artificial Intelligence Center of Excellence. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

- 1. Lima ACES, de Castro LN. Predicting Temperament from Twitter Data. 5th International Congress on Advanced Applied Informatics. 2016.

- 2. Wiszniewski D, Coyne R. Mask and Identity: The Hermeneutics of Self-Construction in the Information. In Renninger K. A., & Shumar W., Building Virtual Communities: Learning and Change in Cyberspace (Learning in Doing: Social, Cognitive and Computational Perspectives) (pp. 191–214). Cambridge University Press. 2002.

- 3. Bakshy E, Hofman JM, Mason WA, Watts DJ. Everyone's an influencer: quantifying influence on twitter. roceedings of the fourth ACM international conference on Web search and data mining. 2011.

- 4. Cha M, Haddadi H, Benevenuto F, Gummadi PK. Measuring User Influence in Twitter: The Million Follower Fallacy. ICWSM. 2010.

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- 8. Golbeck J, Robles C, Turner K. Predicting Personality with Social Media. CHI '11 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, pp. 253–262. 2011.

- 9. Guntuku SC, Lin W, Carpenter J, Ng WK, Ungar LH, Preoţiuc-Pietro D. Studying personality through the content of posted and liked images on Twitter. In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM on web science conference, 2017.

- 15. Bermingham A, Smeaton A. On Using Twitter to Monitor Political Sentiment and Predict Election Results. Sentiment Analysis where AI meets Psychology (SAAIP) Workshop at the International Joint Conference for Natural Language Processing (IJCNLP), (pp. 2–10). Chiang Mai, Thailand. 2011.

- 16. Makazhanov A, Rafiei D. Predicting political preference of Twitter users. Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining (pp. 298–305). Niagara, Ontario, Canada: ACM. 2013.

- 17. Bollen J, Mao H, Pepe A. Modeling Public Mood and Emotion: Twitter Sentiment and Socio-Economic Phenomena. Proceedings of the Fifth International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media (pp. 450–453). Barcelona, Spain: AAAI. 2011.

- 18. Hasan M, Rundensteiner E, Agu E. EMOTEX: Detecting Emotions in Twitter Messages. ASE BIGDATA/SOCIALCOM/CYBERSECURITY Conference, Stanford University, 2014.

- 19. Choudhury MD, Gamon M, Counts S, Horvitz E. Predicting Depression via Social Media. In Proceedings of the 7th International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media. Boston, MA, Jul 8-Jul 10, 2013.

- 20. Resnik P, Garron A, Resnik R. Using topic modeling to improve prediction of neuroticism and depression. Proceedings of the 2013 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural. 2013.

- 21. Coppersmith G, Harman C, Dredze M. Measuring Post Traumatic Stress Disorder in Twitter. Proceedings of the Eighth International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media (pp. 579–582). Ann Arbor, MI: AAAI—Association for the Advancement of Artificial. 2014.

- 22. Sumner C, Byers A, Boochever R, Park G. J. Predicting Dark Triad Personality Traits from Twitter usage and a linguistic analysis of Tweets. Proceedings at the IEEE 11th International Conference on Machine Learning and Applications ICMLA 2012. 2012.

- 23. Calegari Md, Gemignani OH. Temperamento e Carreira (4 ed.). São Paulo: Summus. 2006.

- 25. Hall CS, Lindzey G, Campbell JB. Teorias da Personalidade. Porto Alegre: Artmed. 2000.

- 26. Calegari Md, Gemignani OH. Temperamento e Carreira (4 ed.). São Paulo: Summus. 2006.

- 27. Keirsey D. Please Understand Me II: Temperament Character Intelligence. Prometheus Nemesis Book Company. 1998.

- 28. Myers-Briggs I. The Myers-Briggs type indicator manual. US: Consulting Psychologists Press The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator: Manual. 1962.

- 29. Jung CG. Tipos Psicológicos (4ª ed.). Vozes. 2011.

- 33. Saunders DR. Type Differentiation Indicator: Manual: A Scoring System for Form J of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator. Consulting Psychologists Press, 1987.

- 35. Luyckx K, Daelemans W. Personae: a Corpus for Author and Personality Prediction from Text. Language Resources and Evaluation Conference (LREC). 2008.

- 36. Komisin M, Guinn C. Identifying Personality Types Using Document Classification Methods. Proceedings of the Twenty-Fifth International Florida Artificial Intelligence Research Society Conference. 2012.

- 37. Brinks D, White H. Detection of Myers-Briggs Type Indicator via Text Based Computer-Mediated Communication. CS 229 Machine Learning CS 229 Machine Learning, Stanford. Retrieved Novembro 25, 2015.

- 38. Plank B, Hovy D. Personality Traits on Twitter—or—How to Get 1,500 Personality Tests in a Week. Proceedings of the 6th Workshop on Computational Approaches to Subjectivity, Sentiment and Social Media Analysis, (pp. 92–98). 2015.

- 39. Verhoeven B, Daelemans W, Plank B. TwiSty: A Multilingual Twitter Stylometry Corpus for Gender and Personality Profiling. LREC. 2016.

- 40. Lukito LC, Erwin A, Purnama J, Danoekoesoemo W. Social media user personality classification using computational linguistic. Information Technology and Electrical Engineering (ICITEE), 2016 8th International Conference on (pp. 1–6). IEEE. 2016.

- 41. de Castro LN, Ferrari DG, Introdução à Mineração de Dados: Conceitos Básicos, Algoritmos e Aplicações, Saraiva, 2016.

- 42. Pennebaker JW, Francis ME, Booth RJ. Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count: LIWC2001—Operator’s Manual. Austin, Texas: LIWC.net. Retrieved from http://dingo.sbs.arizona.edu/~mehl/other%20files/LIWC2001.pdf . 2001.

- 45. Toutanova K, Manning CD. Enriching the Knowledge Sources Used in a Maximum Entropy Part-of-speech Tagger. Proceedings of the 2000 Joint SIGDAT Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and Very Large Corpora: Held in Conjunction with the 38th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics—Volume 13 (pp. 63–70). Hong Kong: Association for Computational Linguistics. 2000.

- 46. Fellbaum C. WordNet: An Electronic Lexical Database. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. 1998.

- 48. Powers DMW. Evaluation: From Precision, Recall and F Factor to ROC, Informedness, Markedness & Correaltion. 2007.

- 49. Lopes Tinôco, SLJ. Análise de combinação de classificadores usando uma abordagem multiobjetivo baseada em acurácia e número de classificadores. 2013.

REVIEW article

Temperament and school readiness – a literature review.

- 1 Department of Christian Education, Sts Cyril and Methodius Faculty of Theology, Palacký University, Olomouc, Czechia

- 2 The Center of Evidence-Based Education and Arts Therapies, Faculty of Education, Palacký University, Olomouc, Czechia

This review study was conducted to describe how temperament is related to school readiness. The basic research question was whether there is any relationship between later school success and temperament in children and, if so, what characterizes it. A systematic search of databases and journals identified 27 papers that met the two criteria: temperament and school readiness. The analytical strategy followed the PRISMA method. The research confirmed the direct relationship between temperament and school readiness. There is a statistically significant relationship between temperament and school readiness. Both positive and negative emotionality influence behavior (especially concentration), which is reflected in the approach to learning and school success.

Introduction

Temperament, as a cluster of mental attributes that are presented in the form of experiencing and reacting to stimuli with an effect on emotional expressions and behavior, has an effect on school results amongst children ( Keogh, 2003 ). For school education, therefore, what is important is how the child is able to manage its temperament and project it into activity, perseverance, and balance in response to stimuli ( McClelland and Wanless, 2012 ).

The aim of this review study was to identify the relationship between the temperament of the child and school readiness presented in the scientific literature and how the research activities were constructed.

The definitions of temperament are not uniform in their conception and differ with different authors. Three basic theories have been put forward in relation to temperament in human life during its historical development: physiological theories Hippocrates or Galen ( Ashton, 2013 ), bio-ecological theories (e.g., Thomas and Chess, 1977 ), and behaviorally oriented theories (e.g., Thomas and Chess, 1977 ). In the context of temperament research, current studies indicate terms that refine temperament and its manifestations, such as executive functions, effortful control, and self-regulation. Two basic research questions were identified in the context of the objective.

1. Are there studies that describe the relationship between temperament and school readiness and subsequent success rates in children?

2. If so, how can this relationship be characterized?

Theoretical Background

Temperament.

Temperament is the focus of scientists’ interest in psychology. Perhaps the most prevalent are theoretical approaches to temperament as defined by Buss and Plomin (1975) , Thomas and Chess (1977) , Rothbart and Derryberry (1981) , Goldsmith and Campos (1982) , and Kagan (1984) .

The Kagan approach ( Kagan, 1984 ) is constructed based on biological factors that he considered congenital and may affect behavior. Goldsmith and Campos (1982) provide a definition of temperament as an individual difference in the ability to experience and express primal emotions. Differences in temperament are observable in the intensity of behavioral expressions, facial expressions, gestures, and movements. The definition, which is constructed on the basis of nine dimensions of behavioral styles – activity level, regularity, approach withdrawal, adaptability, threshold of responsiveness, intensity of reaction, quality of mood, attention span/persistence, and distractibility – was used by Thomas and Chess (as cited in Pharis, 1978 ). The model that was designed by Buss and Plomin (1975) was behavior-genetics oriented. It is assumed that early manifestations of temperamental features are hereditary and adapt evolutionally in a child, as responses to its living conditions, and are also relatively stable. Three core dimensions were identified: emotionality (E), activity (A), and sociability (S). The above-mentioned authors represent the primary sources to which most later studies relate. The approach to temperament by Rothbart ( Rothbart and Derryberry, 1981 ) defines temperament as biologically ingrained individual differences in reactivity and self-regulation in emotional, activation, and attention-based processes. Reactivity refers to levels of biological arousal caused by changes in internal and external stimulation, which are captured as dimensions of negative influence and surgency. Self-regulation applies to processes that modulate reactivity and are reflected in a temperamental dimension that requires effortful control.

Temperament is accompanied by relatively permanent individual differences in reactivity and self-control that can be influenced in the course of the child’s development by maturation and experience ( Rothbart and Bates, 1998 ). Differences in temperament are apparent from early childhood, with some children tending toward negativity and bad moods, while others have difficulties adapting to a new environment and people ( Thomas et al., 1963 ; Putnam and Rothbart, 2006 ).

Children’s temperament has been described as a source of multiple categories of behavioral manifestations. The result is the concept of temperament as a three-component structure, which is represented by Surgency/Extraversion, Negative Affectivity, and Effortful Control ( Rothbart, 1988 ; Rothbart and Bates, 1998 , 2006 ; Rothbart and Putnam, 2002 ). In a more detailed concept, the Surgency/Extraversion category is described as impulsive, exhibiting a high degree of activity and courage and, at the same time, a need for satisfaction.

Negative Affectivity is characterized by manifestations of sadness, frustration, and being difficult to calm down. Effortful Control is characterized by the need for control and ability to concentrate ( Rothbart and Putnam, 2002 ). In relation to school readiness and the subsequent success of children, Negative Affectivity is characterized by the above-mentioned authors as a possible source of problems with controlling emotions and thus as a possible source of problems in children’s behavior.

Executive Functions

Executive functions as a term can be described as a collective name for a complex and diverse set of mental processes, the content and scope of which are differently defined. Most often, higher-order cognitive abilities are described using this term, allowing people to use psychological and physical resources effectively in an unknown or under-structured situation. Executive functioning, cognitive functioning, and affectivity can be considered as three fundamental dimensions of human behavior. Executive functions provide “know-how” on how to handle cognitive and affective processes. There is empirical evidence suggesting a strong relationship between temperamental characteristics and executive functions ( Sudikoff et al., 2015 ). Affrunti and Woodruff-Borden (2015) state that the expression of temperament can be influenced by executive functioning. Temperament also includes behavioral aspects, as well as attention-seeking processes, including maintaining orientation and executive control. These skills form the basis for the development of self-regulation ( Rothbart and Hwang, 2002 ).

Effortful Control

The interaction of effortful control and emotion or stress is characterized by Zelazo et al. (2016) using the expressions “hot” effortful control and “cool” effortful control. These are based on the results of behavioral and neuroimaging research. Both types of effortful control are involved in the problem-solving function and varying degrees of motivation and emotion. For a “hot” approach, important situations involve the predominance of motivation and emotion. The “cool” approach works in affectively neutral contexts ( Zelazo and Carlson, 2012 ).

Self-Regulation

The current theoretical basis emphasizes the importance of self-regulation in relation to school readiness. Self-regulation in a broader sense involves the ability to control emotions ( Blair and Raver, 2015 ). Self-regulation offers an important addition to the conceptualization of school readiness because it addresses children’s ability to attend to information, use it appropriately, and inhibit behavior that interferes with learning. However, like the broader concept of school readiness, theories and perspectives on self-regulation have focused on various priorities ( Pan et al., 2019 ).

The level of reactivity is related to the characteristics of the reactions to changes in stimuli that are reflected on several levels (behavioral, autonomous, and neuroendocrine) and display different periods of observable parameters from latency and an increase and then a peak of intensity until relaxation. Self-control influences these processes and influences reactivity ( Rothbart et al., 2004 ).

School Readiness

School readiness is understood as the state when a child enters school adequately prepared to engage in school activities and benefit from the educational situations so that he/she can experience success regarding his/her potential. Kagan (1990) speaks about readiness for learning, which is a state in which the child, thanks to his/her development, is able to learn the individual subjects. Janus (2007) describe school readiness as a level of maturity of the nervous system which allows the child to process specific “school” stimuli and develop his/her skills and knowledge without mental suffering.

Regarding mental development, school readiness is a child’s state when the child’s skills necessary for meeting his/her cognitive, physical, and social needs on entry to school can be employed ( Mashburn and Pianta, 2006 ; Pianta et al., 2007 ; Janus and Gaskin, 2013 ). The developmental level of the child provides the opportunity to safely reflect the needs of schooling in a wider context in terms of cognitive, social, and emotional functions ( Lemelin et al., 2007 ).

In relation to the above, one can also include maturity and physical health, emotional maturity, and the necessary communication skills ( Kagan, 1992 ; Doherty, 2007 ).

Janus and Offord (2000) named the basic domains that are important in relation to a child’s functioning at school, which can at the same time be used as areas for evaluation or in the event of a need for diagnostics of particular functions. These are physical health and well-being, including the necessary development of fine and coarse motor skills. It is also a domain that includes the social skills of responsibility and respect, approach to education, and readiness to explore new things. Attention also needs to be paid to emotional maturity, which includes pro-social behavior and the ability to function in a group. Being able to deal with anxiety and fear and the ability to manage one’s behavior regarding concentration and activity are associated with emotional maturity. According to these authors, the other domains on the list are the level of language skills and the overall level of cognitive functioning in the areas of literacy, mathematical imagination, and motivation to learn. Communication skills and their adequate development as an essential factor for effective schoolwork can be emphasized.

The research scope of the study is focused on the school readiness of children in relation to their temperament. The given age category of the children and their temperament are considered essential with regard to their readiness for, and subsequent success in, school education, as is stated by other expert studies. Vágnerová (2012) considers preschool age to be a period during which the child should be mentally and physically sufficiently mature to begin school attendance, while Al-Hendawi (2013) argues that temperament is a significant parameter of school adaptation and success. Al-Hendawi (2013) also states that the authors of expert studies view temperament from different perspectives.

The aim of the research was to determine whether there are studies that deal with the relationship between temperament, its dimensions, and school readiness.

For this review study, a design was applied that is based on the PRISMA method ( Moher et al., 2015 ) in the context of the theory of Paré and Kitsiou (2017) . Four stages of the work process were created based on this method.

Stage 1– Strategy

The study, and therefore the search for the primary source texts, focused on the period from 1 January 2000 to 29 February 2020, with the selection including articles in scientific journals in English. The search keywords were represented by the following expressions: School readiness; Temperament; Preschool age; School success; Effortful control; Self control; Mood.

The following elements were used for the search strategy: (school N1 readiness) OR (school N1 success); (school N1 readiness) OR (school N1 success) AND mood; (school N1 readiness) OR (school N1 success) AND Effortful control; (school AND readiness) OR (school AND success); (school AND readiness) OR (school AND success) AND Effortful control; (school AND readiness) OR (school AND success) AND mood; (school N/3 readiness) OR (school N/3 success) AND mood AND preschool.

This time span was chosen because the largest number of texts for further analysis was searched for in the databases during this period. The choice of a shorter time span of the margin did not offer sufficient saturation in searching.

Stage 2 – The Selection of Databases for the Search

The MEDLINE, CINAHL, ERIC, EMBASE, PsycINFO, PsycArticles, Web of Science, Google Scholar, Scopus, and Proquest databases were used for the search. The EBSCO Discovery Service was used. A total of 1092 articles were found.

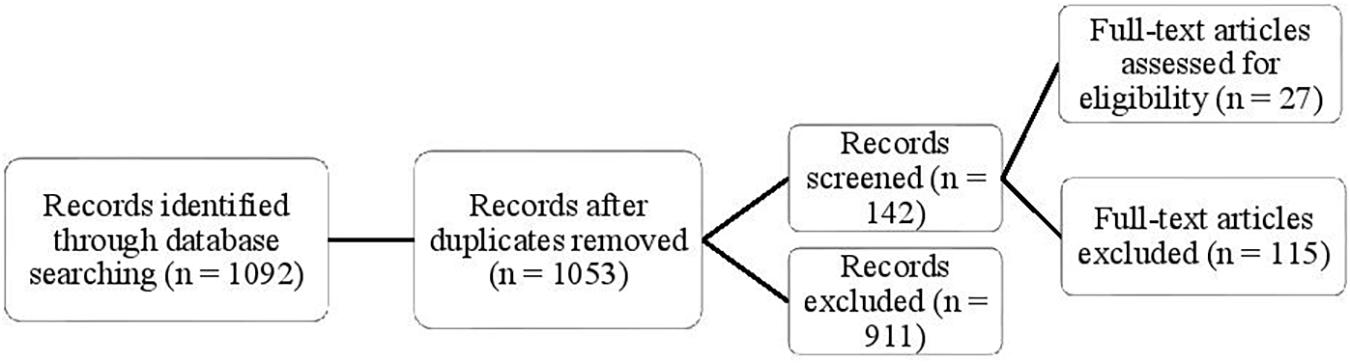

Abstracts were analyzed for all 1092 articles. On the basis of this analysis, those articles that did not match the specified criteria were gradually eliminated. Figure 1 shows what the procedure for the selection of suitable articles looked like.

Figure 1. Flowchart of Searching.

In the last stage a detailed analysis of 142 articles was performed. In all these articles, the key categories “Temperament”, “Executive functions” “Effortful control”, “Self-regulation”, and “School readiness” were used.

On the basis of the analysis of 142 articles, specific groups based on the topics were created. School readiness was related to different variables with an indirect relationship to temperament – ADHD (25 articles), autism (one article), illness and health problems (19 articles), different age categories (28 articles), a conflict between the parents’ and teachers’ expectations of preschool-age children (five articles), and the topic of preschool children and disability (one article). In addition, there was the theory of mind and executive functions (eight articles), language skills (two articles), and the environment of the family and school (eight articles), parents’ temperament (nine articles), and teacher temperament (nine articles).

The narrow selection included 26 or 27 articles whose topics matched the requirements of the relationship between school readiness and temperament, i.e., both the essential categories – school readiness and temperament – appeared in them simultaneously. Only the 27th article ( Miller and Goldsmith, 2017 ) is rather specific because the authors wanted to create an ideal pupil who would be successful at school.

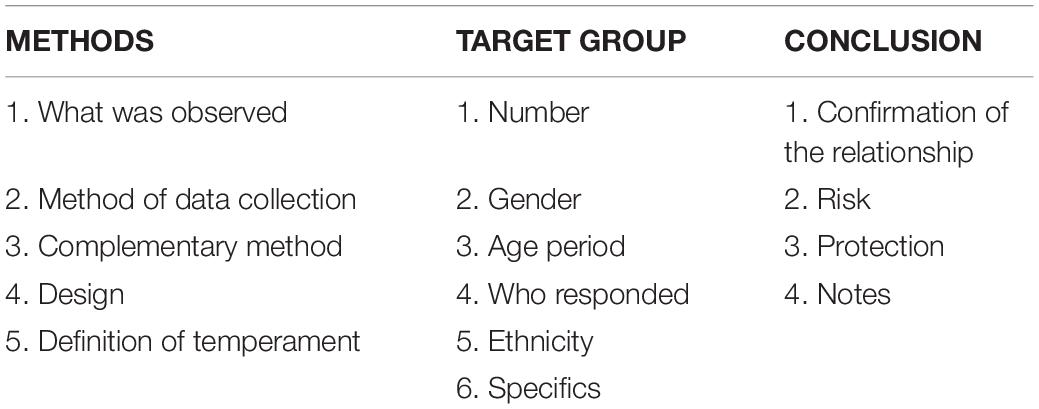

The articles were analyzed qualitatively using a set of qualitative indicators. The indicators were determined in compliance with the research questions as the basis for the research and a more detailed description of the relationship between the child’s temperament and school readiness. On the basis of these criteria, three qualitative indicators were determined: methods, target group, and research results. These indicators were then divided into the sub-groups shown in Table 1 .

Table 1. Qualitative indicators.

The stated qualitative indicators were determined as the basis for further examination and a more detailed description of the relationship between the child’s temperament and school readiness or success in the selected articles.

Qualitative Indicator – Methods

The focus of the selected studies was divided into three fundamental domains: temperament (A), cognitive abilities (B), and social skills (C) (see Table 2 ). In twelve studies ( Schoen and Nagle, 1994 ; Rudasill and Konold, 2008 ; Rudasill and Rimm-Kaufman, 2009 ; Stacks and Oshio, 2009 ; Zhou et al., 2010 ; Gartstein et al., 2016 ; Collings et al., 2017 ; Miller and Goldsmith, 2017 ; VanSchyndel et al., 2017 ; Bryce et al., 2018 ; Beceren and Özdemir, 2019 ; Johnson et al., 2019 ) the authors directly use the term ‘temperament’, while in 15 ( Bramlett et al., 2000 ; Valiente et al., 2008 , 2010 ; Rimm-Kaufman et al., 2009 ; Iyer et al., 2010 ; Rhoades et al., 2011 ; Silva, 2011 ; Valiente et al., 2011 ; Willoughby et al., 2011 ; Al-Hendawi and Reed, 2012 ; Razza et al., 2012 ; Morris et al., 2013 ; Gaias et al., 2016 ; Sawyer et al., 2019 ; Fung et al., 2020 ) they use the term ‘regulation of emotions’, which they perceive as part of temperament. In all the research focused on school readiness, however, the concept of readiness differed, and it was possible to divide it into two basic categories of social skills ( Bramlett et al., 2000 ; Rimm-Kaufman et al., 2009 ; Rudasill and Rimm-Kaufman, 2009 ; Stacks and Oshio, 2009 ; Valiente et al., 2010 ; Zhou et al., 2010 ; Silva, 2011 ; Valiente et al., 2011 ; Willoughby et al., 2011 ; Al-Hendawi and Reed, 2012 ; Morris et al., 2013 ; Gaias et al., 2016 ; Gartstein et al., 2016 ; VanSchyndel et al., 2017 ; Johnson et al., 2019 ; Beceren and Özdemir, 2019 ) and cognitive skills ( Schoen and Nagle, 1994 ; Rhoades et al., 2011 ; Valiente et al., 2011 ; Razza et al., 2012 ; Morris et al., 2013 ; Collings et al., 2017 ; Miller and Goldsmith, 2017 ; Bryce et al., 2018 ; Johnson et al., 2019 ; Sawyer et al., 2019 ; Rimm-Kaufman et al., 2009 ; Valiente et al., 2010 ; Zhou et al., 2010 ; Willoughby et al., 2011 ; Gaias et al., 2016 ; Gartstein et al., 2016 ; VanSchyndel et al., 2017 ). In the area of cognitive skills, the authors observed reading and mathematical concepts ( Valiente et al., 2010 ; Morris et al., 2013 ; Gaias et al., 2016 ; Johnson et al., 2019 ), language skills ( Schoen and Nagle, 1994 ; Rhoades et al., 2011 ), and in two cases both the skills ( Razza et al., 2012 ; Sawyer et al., 2019 ).

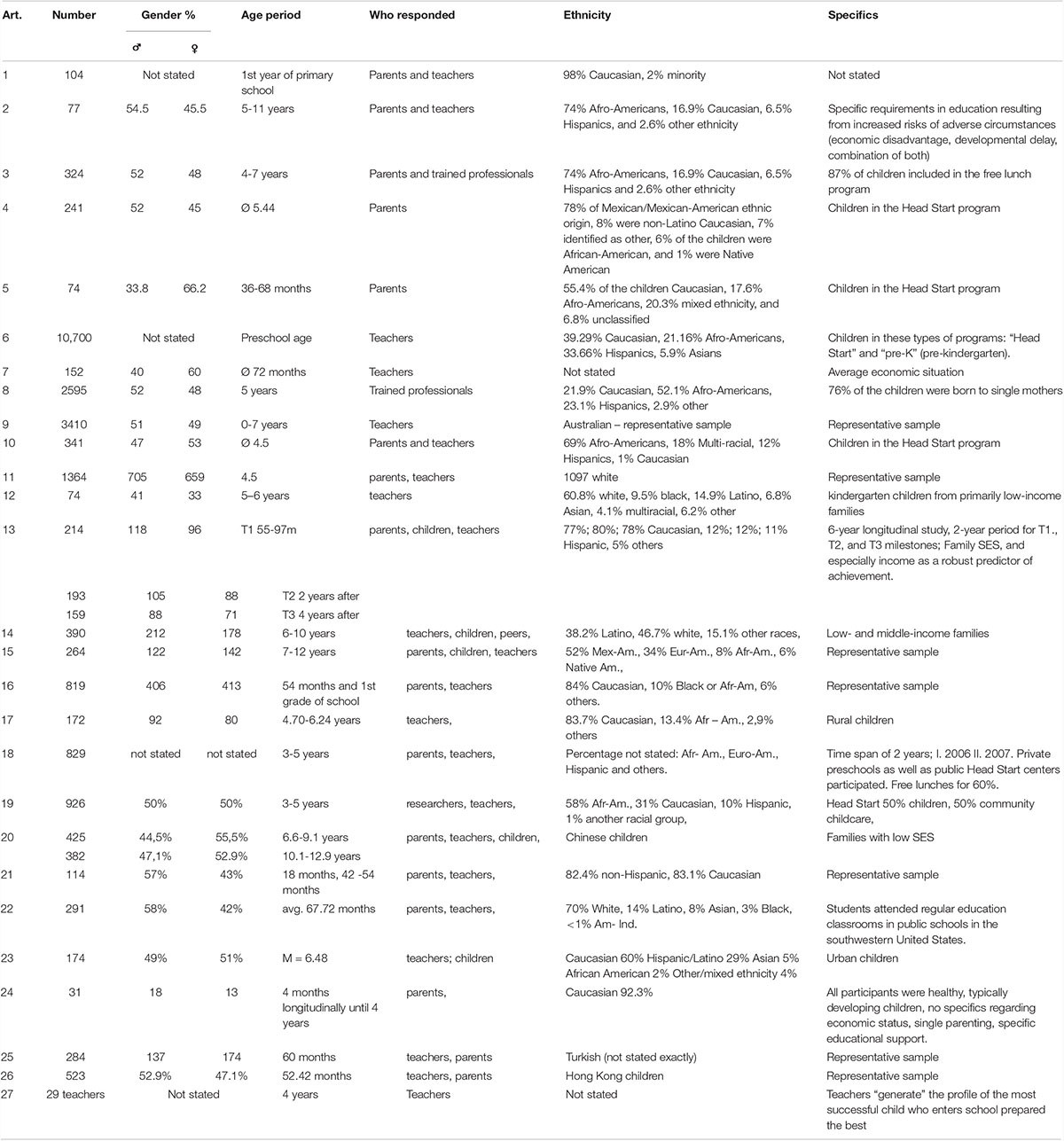

Table 2. Qualitative indicator – target group.

To characterize temperament, different tools were used, in eleven cases the CBQ questionnaire ( Rudasill and Konold, 2008 ; Rudasill and Rimm-Kaufman, 2009 ; Iyer et al., 2010 ; Valiente et al., 2010 ; Zhou et al., 2010 ; Silva, 2011 ; Valiente et al., 2011 ; Morris et al., 2013 ; Gaias et al., 2016 ; Miller and Goldsmith, 2017 ; Bryce et al., 2018 ), which will also be used in our case. In order to assess the level of cognitive and social skills, certified tools were mainly used, in one case ( Johnson et al., 2019 ) a tool that the researchers developed themselves, and in two cases, observation was used ( Rimm-Kaufman et al., 2009 ; Rudasill and Rimm-Kaufman, 2009 ).

The definition of temperament is then adapted for the purpose of the studies. In eight cases, the authors put an emphasis on individual differences in their definitions ( Bramlett et al., 2000 ; Rudasill and Konold, 2008 ; Rudasill and Rimm-Kaufman, 2009 ; Valiente et al., 2010 ; Gartstein et al., 2016 ; Collings et al., 2017 ; Bryce et al., 2018 ; Johnson et al., 2019 ), in eleven cases they emphasized self-control ( Rimm-Kaufman et al., 2009 ; Valiente et al., 2010 , 2011 ; Willoughby et al., 2011 ; Gaias et al., 2016 ; Gartstein et al., 2016 ; Collings et al., 2017 ; Miller and Goldsmith, 2017 ; Bryce et al., 2018 ; Johnson et al., 2019 ; Sawyer et al., 2019 ), and in five cases they stressed the biological basis ( Bramlett et al., 2000 ; Rudasill and Konold, 2008 ; Rudasill and Rimm-Kaufman, 2009 ; Al-Hendawi and Reed, 2012 ; Sawyer et al., 2019 ). Morris et al. (2013) , Beceren and Özdemir (2019) , Johnson et al. (2019) , and Fung et al. (2020) stress the influence of temperament on emotions in their definition and the influence on children’s social skills is emphasized in nine studies ( Schoen and Nagle, 1994 ; Valiente et al., 2008 ; Stacks and Oshio, 2009 ; Iyer et al., 2010 ; Zhou et al., 2010 ; Rhoades et al., 2011 ; Silva, 2011 ; Razza et al., 2012 ; VanSchyndel et al., 2017 ).

Qualitative Indicator – Target Group

The numbers of respondents were representative in relation to the research that was analyzed. In longitudinal studies, there were research studies with large numbers of respondents (more than 1000) ( Razza et al., 2012 ; Johnson et al., 2019 ; Sawyer et al., 2019 ), but also one research study involving 31 respondents ( Gartstein et al., 2016 ). For most other research studies, the number of respondents ranged between 100 and 1000 ( Schoen and Nagle, 1994 ; Bramlett et al., 2000 ; Valiente et al., 2008 , 2010 , 2011 ; Rimm-Kaufman et al., 2009 ; Rudasill and Rimm-Kaufman, 2009 ; Iyer et al., 2010 ; Zhou et al., 2010 ; Rhoades et al., 2011 ; Silva, 2011 ; Willoughby et al., 2011 ; Gaias et al., 2016 ; Collings et al., 2017 ; VanSchyndel et al., 2017 ; Bryce et al., 2018 ; Beceren and Özdemir, 2019 ; Fung et al., 2020 ). The exceptions consisted of some studies ( Stacks and Oshio, 2009 ; Al-Hendawi and Reed, 2012 ; Morris et al., 2013 ) in which there were fewer than 100 respondents and one case with 1364 respondents ( Rudasill and Konold, 2008 ). In one study ( Miller and Goldsmith, 2017 ) the respondents were teachers whose task was to create basic categories which they could use to assess a child’s school readiness.

In four cases ( Bramlett et al., 2000 ; Silva, 2011 ; Miller and Goldsmith, 2017 ; Johnson et al., 2019 ) the authors of the study do not state the results regarding gender. In the studies by Schoen and Nagle (1994) , Stacks and Oshio (2009) , Valiente et al. (2010) , and VanSchyndel et al. (2017) the gender ratio between boys and girls was 40% to 60% and in the remaining studies the ratio was around 50% in all cases.

The age span of the respondents was between 0 and 12 years of age. The age of the respondents was associated with the research aim (see Table 2 and the glossary accompanying the table). The information about the respondents was in all cases (except in one case, Gartstein et al., 2016 ), obtained from the responses of teachers or trained researchers and in 14 cases ( Bramlett et al., 2000 ; Rudasill and Konold, 2008 ; Valiente et al., 2008 , 2010 , 2011 ; Rudasill and Rimm-Kaufman, 2009 ; Zhou et al., 2010 ; Rhoades et al., 2011 ; Silva, 2011 ; Al-Hendawi and Reed, 2012 ; Collings et al., 2017 ; VanSchyndel et al., 2017 ; Beceren and Özdemir, 2019 ; Fung et al., 2020 ) also from parents. In three cases, information was also obtained from children ( Iyer et al., 2010 ; Zhou et al., 2010 ; Valiente et al., 2011 ).

Schoen and Nagle (1994) , Miller and Goldsmith (2017) , and Beceren and Özdemir (2019) do not state ethnicity in their studies. Sawyer et al. (2019) state that the research was carried out on a representative sample of the Australian population, similarly to Bramlett et al. (2000) , who state that 98% of their sample was Caucasian. In the case of these two studies, the aim was not to compare the influence of temperament on school success with regard to ethnicity, but primarily a description of the given relationship in a representative sample of the given population. Silva (2011) cites ethnicity, but not the percentual distribution. Rudasill and Konold (2008) , Zhou et al. (2010) , and Fung et al. (2020) presented mono-ethnic samples; in the first case they were Caucasians, the second study involved children from Hong Kong, and in the third article the respondents were from China. In the other studies the percentages of the ethnic groups are presented.

Schoen and Nagle (1994) , Bramlett et al. (2000) , Rudasill and Konold (2008) , Rudasill and Rimm-Kaufman (2009) , Valiente et al. (2010) , Gartstein et al. (2016) , Beceren and Özdemir (2019) , Sawyer et al. (2019) , and Fung et al. (2020) do not state any specifics in relation to their respondents or state that it was a representative sample. Miller and Goldsmith (2017) aimed their research at creating a profile of the most successful child who enters school prepared to the maximum extent. Rimm-Kaufman et al. (2009) reported that their respondents were exclusively children from villages, while in contrast Gaias et al. (2016) chose children from cities. In other cases, the authors studied children who came from a socially or economically endangered environment. They were specifically children who were born to single mothers ( Razza et al., 2012 ), children who were included in the “Head Start” program ( Stacks and Oshio, 2009 ; Rhoades et al., 2011 ; Silva, 2011 ; Willoughby et al., 2011 ; Bryce et al., 2018 ; Johnson et al., 2019 ), and children who were included in the free lunch program ( Silva, 2011 ; Collings et al., 2017 ). Iyer et al. (2010) , Zhou et al. (2010) , Valiente et al. (2011) , Al-Hendawi and Reed (2012) , and Morris et al. (2013) were interested in children who displayed specific requirements for education as a result of increased risk of adverse circumstances (economic disadvantage, developmental delay, or a combination of both).

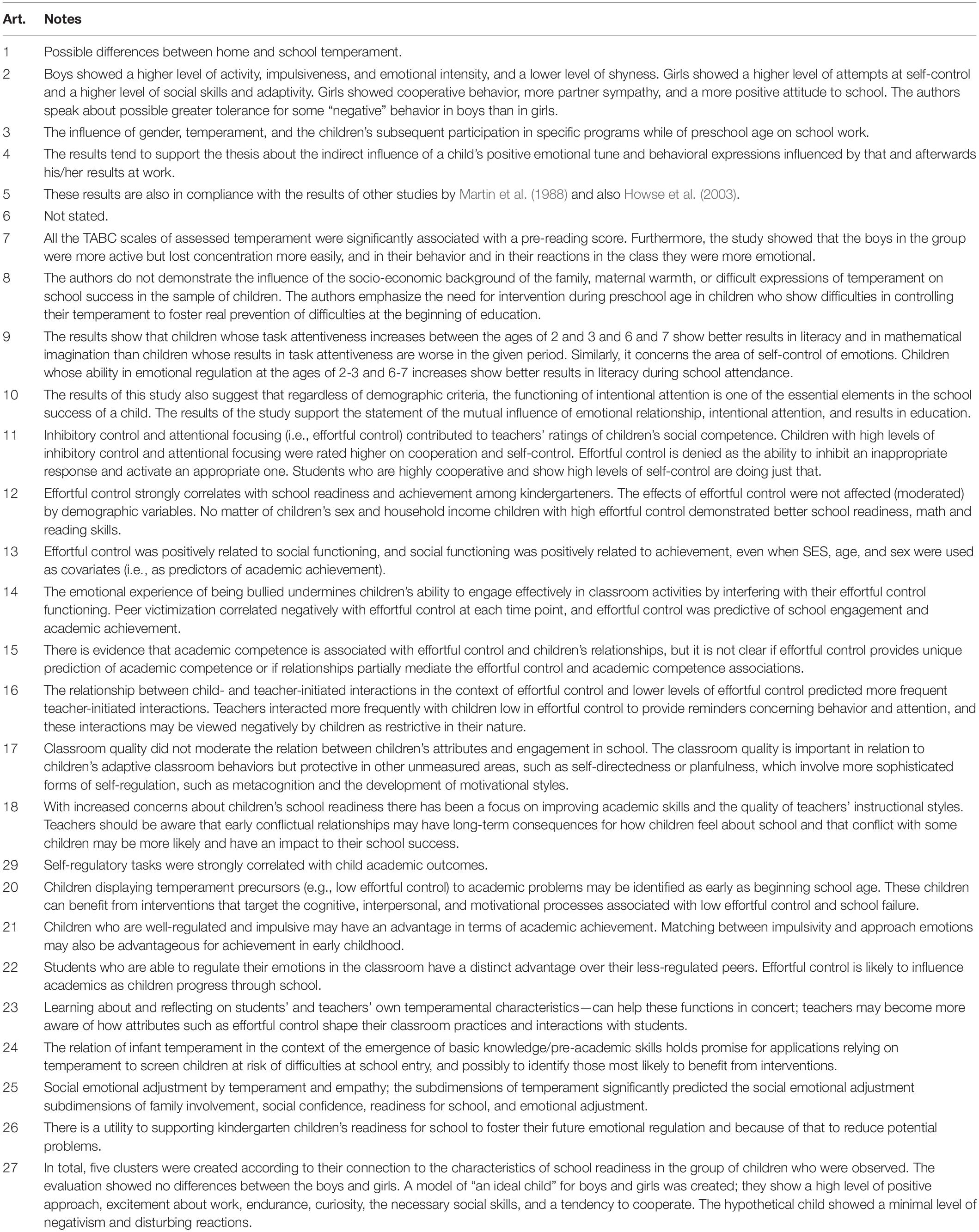

Qualitative Indicator – Conclusion

In the case of the study by Bryce et al. (2018) , it was not possible to confirm a hypothetical chain process: child’s positive emotionality → emotional engagement in kindergarten → behavioral expressions in kindergarten → educational results in kindergarten. In other cases, the link between temperament and school readiness or subsequent school success was confirmed.

In some cases ( Rudasill and Konold, 2008 ; Valiente et al., 2008 , 2010 , 2011 ; Rudasill and Rimm-Kaufman, 2009 ; Iyer et al., 2010 ; Zhou et al., 2010 ; Rhoades et al., 2011 ; Silva, 2011 ; Al-Hendawi and Reed, 2012 ; Morris et al., 2013 ; Gaias et al., 2016 ; Gartstein et al., 2016 ; Collings et al., 2017 ; Miller and Goldsmith, 2017 ; VanSchyndel et al., 2017 ; Bryce et al., 2018 ; Beceren and Özdemir, 2019 ; Johnson et al., 2019 ; Fung et al., 2020 ) the authors were further interested in whether temperament can be seen as a risk or protective factor. In most cases, it was found that higher Effortful Control has a positive relationship to greater school readiness – the success rate and lower Effortful Control can predict behavioral problems and thus problems at school ( Valiente et al., 2008 , 2010 , 2011 ; Iyer et al., 2010 ; Zhou et al., 2010 ; Morris et al., 2013 ; Gartstein et al., 2016 ; VanSchyndel et al., 2017 ). Rudasill and Rimm-Kaufman (2009) , Silva (2011) , and Gaias et al. (2016) add that the value of Effortful Control can influence the teacher’s relationship with the child and thus the child’s school readiness and also later school success. Al-Hendawi and Reed (2012) found that negative emotionality has a significant effect on adaptivity and schoolwork and can become a predictor of inappropriate behavior. In contrast, Johnson et al. (2019) did not confirm that problems in the area of a child’s temperament can be perceived as a significant predictor of prosocial behavior. There is a statistically significant relationship between temperament and school readiness. Both positive and negative emotionality influence behavior (especially concentration), which is reflected in the approach to learning and school success.

Collings et al. (2017) suggest that there was a positive effect of a previous intervention on temperament, confirmed in the individual items of school performance. Their results for the boys who participated in the intervention program were better in the areas of literacy and mathematics than was the case in boys who did not participate. Bryce et al. (2018) state that positive emotionality significantly influenced behavior in children in kindergarten. Rudasill and Konold (2008) , Rhoades et al. (2011) , Beceren and Özdemir (2019) , and Fung et al. (2020) characterized the child’s maturity in the context of how he/she is able to control his/her temperament so that it can function as a supportive factor in education. Similar conclusions were also reached by Miller and Goldsmith (2017) . In their view, children who were able to regulate their emotions were able to react better in socially appropriate ways and focus their attention, which facilitates learning and provides higher chances of success in school education.

In addition, difficult temperament at an early age can lead to low parental involvement at age three. The role of difficult temperament, poor maternal involvement, and externalizing behavior may be partially responsible for the continuity that has been observed in antisocial behavior over time ( Walters, 2014 ).