- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

IResearchNet

Academic Writing Services

Sociology definition.

Sociology Subfields

Origins and national traditions in sociology, institutionalization of sociology, current challenges and issues in sociology.

Many disciplines have a clearly defined subject matter, although very often this is due to the absence of methodological scrutiny and uncritical consensus, as in the general view that ‘‘the past’’ is the subject domain of historians while political scientists study ‘‘politics.’’ Sociologists generally have a tougher time in defending their territory than other disciplines, even though they unhesitatingly take over on the territory of others. Sociology’s subject domain can arguably be said to be the totality of social relations or simply ‘‘society,’’ which Durkheim said was a reality sui generis. As a reality in itself the social world is more than the sum of its parts. There has been little agreement on exactly what these parts are, with some positions arguing that the parts are social structures and others claiming that society is simply made up of social actors and thus the subject matter of sociology is social action. The emphasis on the whole being greater than the sum of the parts has led some sociologists to the view that sociology is defined by the study of the relations between the different parts of society. This insight has tended to be reflected in a view of society as a movement or process. It would not be inaccurate to say that sociology is the social science devoted to the study of modern society.

In terms of theory and methodology, sociology is highly diverse. The paradigms that Thomas Kuhn believed to be characteristic of the history of science are more absent from sociology than from other social sciences. Arguably, anthropology and economics have more tightly defined methodological approaches than sociology. As a social science, sociology can be described as evidence based social inquiry into the social world and informed by conceptual frameworks and established methodological approaches. But what constitutes evidence varies depending on whether quantitative or qualitative approaches are adopted, although such approaches are not distinctively sociological. There is also considerable debate as to the scientific status of sociology, which was founded to be a social science distinct from the natural sciences and distinct from the human sciences. The diversity of positions on sociology today is undoubtedly a matter of where sociology is deemed to stand in relation to the experimental and human sciences. While it is generally accepted that sociology is a third science, there is less consensus on exactly where the limits of this space should be drawn. This is also a question of the relation of sociology to its subject matter: is it part of its object, as in the hermeneutical tradition; is it separate from its object, as in the positivist tradition; or is it a mode of knowledge connected to its object by political practice, as in the radical tradition?

A discipline is often shaped by its founding figures and a canon of classical works. It is generally accepted today that the work of Marx, Weber, and Durkheim has given to sociology a classical framework. However, whether this canon can direct sociological research today is highly questionable and mostly it has been relegated to the history of sociology, although there are attempts to make classics relevant to current social research (Shilling & Mellor 2001). Such attempts, however, misunderstand the relation between the history of a discipline and the actual practice of it. Classic works are not of timeless relevance, but offer points of reference for the interpretation of the present and milestones in the history of a discipline. For this reason the canon is not stable and should also not be con fused with social theory: it was Parsons in the 1930s who canonized Weber and Durkheim as founding fathers; in the 1970s Marx was added to the list – due not least to the efforts of Giddens – and Spencer has more or less disappeared; in the 1980s Simmel was added and in the present day there is the rise of contemporary classics, such as Bourdieu, Bauman, Luhmann, Habermas, and Foucault, and there are recovered classics, such as Elias. It is apparent from a cursory look at the classics that many figures were only later invented as classical sociologists to suit whatever project was being announced. The word ‘‘invented’’ is not too strong here: Marx did not see himself as a sociologist, Weber was an economic historian and rarely referred to sociology as such, and Foucault was a lapsed psychiatrist; all of them operated outside disciplinary boundaries.

The impact of Foucault on sociology today is a reminder that sociology continues to change, absorbing influences from outside the traditional discipline. The range of methodological and theoretical approaches has not led to a great deal of synthesis or consensus on what actually defines sociology. Since the so called cultural turn in the social sciences, much of sociology takes place outside the discipline itself, in cultural studies, criminology, women’s studies, development studies, demography, human geography, and planning, as well as in the other social and human sciences. This is increasingly the case with the rise of interdisciplinarity and more so with post disciplinarity, wherein disciplines do not merely relate to each other but disappear altogether. Few social science disciplines have made such an impact on the wider social and human science as sociology, a situation that has led to widespread concern that sociology may be disappearing into those disciplines that it had in part helped to create (Scott 2005).

- Deviance Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Environmental Sociology

- Media Sociology

- Medical Sociology

- Political Sociology

- Sociology of Aging

- Sociology of Crime

- Sociology of Culture

- Sociology of Education

- Sociology of Family

- Sociology of Gender

- Sociology of Knowledge

- Sociology of Law

- Sociology of Organizations

- Sociology of Race

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Science

- Sociology of Sport

- Urban Sociology

In the most general sense sociology arose as a mode of knowledge concerned with the moral problems of modernity. The origins of sociology go back to the discovery of the existence of the social as a specific reality independent of the state and the private domain of the house hold. The eighteenth century marks the emergence of social theory as a distinctive form of intellectual inquiry and which gradually becomes distinguished from political theory. The decline of the court society and the rise of civil society suggested the existence of the social as a distinctive object of consciousness and reflection. Until then it was not clear of what ‘‘society’’ consisted other than the official culture of the court society. By the eighteenth century it was evident that there was indeed an objective social domain that could be called ‘‘society’’ with which was associated the public. This coincided with the rise of sociology.

One of the first major works in the emergence of sociology was Montesquieu’s The Spirit of the Laws, which brought about the transformation of political theory into sociology. The central theme in this work, which was published in 1748, was that society is the source of all laws. Society was expressed in the form of conditioning influences on people, shaping different forms of life. Durkheim claimed that the notion of an underlying spirit or ethos that pervades social institutions was a resonating theme in modern sociological thought from Montesquieu – a tread that is also present in Weber’s The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. The Spirit of the Laws demonstrated the socio logical notion that social laws are socially and historically variable, but not to a point that human societies have nothing in common. According to Montesquieu, who was acutely aware of the diversity of societies, they differ most notably according to geographical factors, which have a conditioning influence in norms, morals, and character. His empirical method demonstrated a connection between climate and social customs and gave great attention to the material condition of life. It was this use of the empirical method to make testable hypotheses that Durkheim admired and which had a lasting influence on French sociology to Bourdieu and beyond.

Although generally regarded as one of the founders of modern political philosophy, Rousseau anticipated many sociological theories. He was one of the first to identify society as the source of social problems. In the Discourse on the Origin of Inequality, published in 1755, he argued that inequality is not a natural characteristic, but a socially created one for which individuals themselves are not responsible. The notion of the ‘‘general will’’ – itself based on Montesquieu’s ‘‘spirit of the laws’’ – influenced Durkheim’s concept of collective representations. The general will signified the external normative and symbolic power of collective beliefs. But Rousseau’s enduring legacy is the theory of the social contract, which can be seen as an early notion of community as the basis of society and the state as a political community. In his most famous work, The Social Contract, published in 1762, he postulated the existence of the social contract to describe the social bond that makes society possible.

The discipline of sociology has been strongly influenced by the French sociological tradition, for in France social science – where the term first arose – was more advanced as an officially recognized activity. Auguste Comte coined the term sociology to refer to the science of social order and which he believed to be the ‘‘queen of the sciences.’’ Comte’s plea for a positivistic sociology must be seen in the context of the age, where social inquiry was largely associated with the speculative approaches of Enlightenment intellectuals and the officers of the restored ancien regime. Against the negative critiques of the intellectuals, Comte wished sociology to be a positive science based on evidence rather than speculation. But his legacy was his notion of sociology as the queen of the sciences. In this grandiose vision of sociology, the new science of modernity not only encapsulated positivism, but it also stood at the apex of a hierarchy of sciences, providing them with an integrative framework. While few adhered to this vision, the idea that sociology was integrative rather than a specialized science remained influential and has been the basis of the idea of sociology as a science that does not have its own subject matter but interprets the results of other sciences from the perspective of a general science of society. From the nineteenth century this general conception of sociology became linked with the problem of the moral order of society in the era of social and political unrest that followed the French Revolution. This is particularly evident in the sociology of Durkheim, whose major works were responses to the crisis of the moral order. This was most acutely the case with Suicide, which was one of the first works in professional sociology, but was also the central question in the Division of Labour in Society. Thus it could be said that the French tradition reflected a general conception of sociology as the science of the social problems of modern society.

Attention must also be paid to the Scottish origins of sociology, which go back to the moral philosophers of the Scottish Enlightenment, who can be regarded as early sociologists in that they recognized the objectivity of society (Strydom 2000). This tradition, too, provided a basis for a tradition of sociology as a general social science of modernity. Adam Ferguson’s Essay on the Origin of Civil Society, published in 1767, emphasized the role of social conflict and in terms very different from John Hobbes’s account of conflict and individual egoism. For Ferguson, conflict between nations produces solidarity and makes civil society as a universal norm possible. He recognized that society is always more than the sum of its parts and can never be reduced to its components. In marked contrast to the prevailing ideas of the age, Ferguson argued that the state of nature is itself a social condition and that sociality is natural. John Millar’s Origin of the Distinction of Ranks, published in 1770, contained one of the first discussions of social class and can be seen as a pioneering work in historical sociology. Millar and Ferguson were particularly interested in the historical evolution of society, which they viewed in terms of a model of progress. But it was in the writings of Adam Smith that the notion of progress was most pronounced. Smith developed moral philosophy into a theory of political economy coupled with a theory of progress that was influential for over a century later. Society progresses in four historical stages, he argued, which can be related to stages – hunting, pastoral, agricultural, and commercial – in the development of the means of subsistence. Commercial society is based on private property and the economic pursuit of individual interest. Smith argued, however, that the well being of commercial society and indeed the very fact of society is due to a collective logic – which he called an ‘‘invisible hand’’ – at work, which ensures that individual actions function to serve collective goals. Although Smith came to personify laissez faire capitalism, his concerns were largely philosophical and must be understood in the intellectual and political context of the age. Like the other moral philosophers in Scotland, Smith was acutely aware of the contingent nature of the human condition, which could never be explained by natural law. Moral norms and the rules of justice must be devised in ways that function best for the needs of society and in ways that will reduce evil and suffering. In this respect Smith, Ferguson, and Millar established a vision of sociology as a moral science of the social world, the outcome of which was that the social and the natural were separated from each other and sociology became the science of the social.

From its early origins in Enlightenment thought, sociology emerged along with the wider institutionalization of the social sciences from the end of the nineteenth century. In France, as already noted, it was most advanced and the Durkheimian tradition established a firm foundation for modern French sociology, which was based on a strong tradition of empirical inquiry. In Germany, where sociology emerged later, it was more closely tied to the humanities. While in France sociology had become relatively independent of philosophy, in Germany a tradition of humanistic sociology developed on the one side from the neo Kantian philosophy and on the other from Hegelian Marxism. While Weber broke the connection with psychology that was so much a feature of the neo Kantian tradition, German sociology remained strongly interpretive and preoccupied with issues of culture and history. Weber himself was an economic historian primarily concerned with the problem of bureaucracy, but increasingly came to be interested in comparative analysis of the world religions and the relation between cultural and moral meaning with economic activity. His work was testimony to the belief that social inquiry can shed light on moral values that are constitutive of the social condition. Where German sociology as represented by Weber was concerned with the problem of subjective meaning, French sociology was animated by the concern with social moral ity. For this reason it is plausible to argue, as Fuller (1998) claims, that sociology has been a kind of secular theology. Underlying both the German and French traditions has been a vision of sociology – distilled of Comtean positivism – as a general social science of modern society.

According to Talcott Parsons in one of the classic works of modern sociology, The Structure of Social Action (1949), Hobbes and Locke articulated the basic themes of sociology, namely the problem of social order. But we cannot speak of a British sociological tradition before the Scottish Enlightenment thinkers mentioned above. Hobbes and Locke have been claimed by political theory and were not influential in sociological thought. Modern British sociology initially emerged from the work of such Victorian liberal reformers as J. S. Mill and Herbert Spencer. Although Spencer broke from Mill’s utilitarianism, his biological evolutionism led to a restrictive approach that has now been largely discredited. British sociology has on the whole been shaped by a vision of sociology as a social science concerned with specific issues. By far the dominant trend has been a view of sociology concerned with class and social structure. The social relations and associated social institutions – class mobility, work and industry, education, poverty, and social problems – that defined sociology for several decades were of course closely linked to industrial society and the kind of political values it cultivated. Modern British sociology was strongly influenced by Marxism. Another significant British tradition in sociology was one allied to social policy, as reflected in the tradition associated with Hobhouse and the London School of Economics, where sociology and social policy were closely related. To this tradition belongs T. H. Marshall and what broadly can be called policy relevant social science. In the British tradition the continental European vision of sociology as a general social science has mostly been absent. However, it must be noted that much of modern British sociology was the product of continental European traditions that had come to Britain since the 1930s. Sociologists such as Norbert Elias and Karl Mannheim who came from Germany and John Rex from South Africa gave to British sociology a varied character that was not encapsulated in a specific tradition. In addition, of course, there was the Marxist tradition, beginning with Marx himself in exile in London. Nevertheless, British sociology tended to reflect a view of sociology as in part having a special subject matter: class and social structure.

There is little doubt that the international prestige of sociology in the twentieth century would not have been possible were it not for the tremendous expansion and institutionalization of the discipline in the US. American sociology arose out of economics and was professionalized relatively early, with the foundation of the American Sociological Society by Albion Small and others in 1905. The Society, renamed American Sociological Association in 1959, in fact was a breakaway movement from the American Economic Association. Small, Charles Horton Cooley, and William Thomas were the most influential figures in shaping American sociology, which was closely related to the American philosophical tradition of pragmatism at least until the 1940s. Comparable to the British reformist concern with social policy, pragmatism reflected a belief in the public role of social science. Early American sociology was thus shaped in the spirit of scientific knowledge assisting in solving social problems (Lynd 1939). The twentieth century, however, saw a growing professionalization of American sociology, which shed its reformist origins. On the one side, a strong tradition of empirical sociology developed which was largely quantitative and often value free to a point that it ceased to be anything more than hypothesis testing. On the other side, a tradition of grand theory associated with Parsons developed, but it rarely intersected with the empirical tradition. Existing outside these traditions was the remnant of the early pragmatist tradition in the sociology of symbolic interactionism, stemming from George Herbert Mead.

This short survey of some of the major national histories of sociology tells us that no one national tradition has prevailed and within all these national traditions are rival traditions. This has led some critics to complain that sociology has somehow failed. Horowitz (1993) complains that sociology is in crisis due to its specialization and also due to its over politicization. Sociology is decomposing because it has lost its way. The great classical visions of sociology no longer prevail and the discipline has lost its integrity. Much of what is called sociology is merely untheoretical empirical case studies, he argues. Such pessimistic views often depend on whether one believes that sociology is based on a single method or vision that can provide a foundation for the discipline. But this may be too much to demand. It is certainly the case that a single school or method has not emerged to define the discipline, but this could also be said to be the case for much of the social and human sciences. It would be an over simplification to characterize the history of sociology as a process of decomposition or fragmentation of an inner unity guaranteed by a discipline. The classical tradition was not a unified one and much of this has been reflexively constituted by a discipline that changes in response to changes in the nature of society.

Back to Top

The institutionalization of sociology coincided with the formation of disciplines in the twentieth century. As a profession, one of the early statements was Weber’s address ‘‘Science as a Vocation’’ in 1918, which although addressed to the wider question of a commitment to science as a different order of commitment than to politics, has been recognized as one of the major expressions of the professionalization of sociology (Weber 1970). The notion of occupation invoked referred to both the idea of sociology as a profession and as a vocation whose calling required certain sacrifices, one of which was not to seek in science answers to fundamental moral questions. As a science, sociology is concerned with providing explanations about social phenomena and in Weber’s view it also has a role to play in guiding social policy.

In its formative period sociology had to compete with the natural sciences. As social science gained general acceptability as an area distinct from both the human sciences and the natural sciences, sociology found that its greatest challenges came in fact from the more established of the social sciences (Lepenies 1988). In Britain the prestige of anthropology overshadowed sociology. The older disciplines, geography and economics, as well as political science tended to command greater prestige than sociology, which never held the same degree of reliance to the mission of the national state. It must be borne in mind that much of social science owed its existence to its relation to the state: it was the science of the social institutions of the modern state.

The institutionalization of sociology did not fully commence until the period following World War II, when the discipline expanded along with the rise of mass higher education. The professionalization and institutionalization of sociology was marked by the foundation of academic journals such as the American Journal of Sociology, founded in 1895, and the later American Sociological Review. Professional associations such as the American Sociological Association and the British Sociological Association, founded in 1951, greatly enhanced the professionalization of sociology as a discipline, which subsequently underwent a process of internal differentiation with new subfields emerging, ranging from urban sociology and industrial sociology to political sociology, historical sociology, and cultural sociology. By the 1960s sociology became increasingly taught in secondary schools and in the 1970s it became an A level subject in British schools. The 1960s and 1970s saw a tremendous expansion in the discipline in terms of student enrollments and teaching and research careers. In this period sociology became recognized by governments as a major social science and many chairs were created. Socio logical research became recognized by the principal national research foundations and acquired prestige within the university system. In the US there are over 200 sociology journals, a professional associational membership of some 14,000, and more students major in sociology (25,000) annually than in history and economics (Burawoy 2005a). As sociology became one of the major social sciences in universities throughout the world, it became increasingly seen as the most comprehensive science of society. This was viewed by some as a source of the strength and relevance of sociology, but in the view of others it was in danger of becoming a pseudo science, lacking subject specialization, since when sociologists specialize they cease to be sociologists. Neo positivist philosophies attempted to check the dangers of over generalization, while the growing politicization of the discipline that came with its widening social base led to fears that sociology was too closely linked to radical causes, such as Marxism.

Many influential sociologists openly questioned the institutionalization of sociology. If the first era was one of the struggle for the institutionalization of the discipline, the phase that drew to a close in the 1970s was one that was marked by calls for the political engagement of sociology with everyday life. Gouldner (1970) argued that sociology needs to be reoriented to be of relevance to society. In his view, sociology went through four main phases: sociological positivism in nineteenth century France, Marx ism, classical European sociology, and finally American structural functionalism as represented by Parsons. Contemporary sociology must articulate a new vision based on a completely different sense of its moral purpose. For Gouldner, this had to be a reflexive sociology and one that was radical in its project to connect sociology to people’s lives. The purpose of sociology is to enable people to make sense of society and to connect their own lives with the wider context of society.

This turn to a reflexive understanding of sociology had been implicit in C. Wright Mills’s Sociological Imagination, which was published in 1959 and was widely read in the 1960s and 1970s. Sociologists such as Mills and Gouldner were opposed to the depoliticized kind of sociology that was emerging in the US. They wanted to recover the moral purpose of sociology that had become lost with its institutionalization in specialist subfields. Mills provided a definition of sociology that continues to be relevant: ‘‘The sociological imagination enables us to grasp history and biography and the relations between the two within society. That is its task and promise’’ (Mills 1970: 12). This conception of sociology was as much opposed to general theory as it was to administrative social research. Mills was primarily inspired by the American pragmatic tradition, which predisposed him to be critical of social science that was cut off from the practical purposes of improving social well being.

The vision of sociology articulated by Mills was not too far removed from the continental European conception of sociology as a diagnosis of the age. In this tradition, which was represented by a broad range of sociologists, such as the Frankfurt School and the humanistic tradition of western Marxism, sociology was connected to social renewal and was primarily a critical endeavor. As represented in the pro grammatic thought of Theodor Adorno, sociology must recover its mission in philosophical thought as a mode of critical thinking. For Adorno, the rise of neo positivism had a detrimental effect on sociology, which had the promise to become the leading critical science of what Daniel Bell and Alain Touraine in their respective works called the ‘‘post industrial society.’’ Habermas (1978) outlined the basis of a view of sociology as concerned with critical knowledge tied to an interest in human emancipation.

Since the 1970s, which saw the expansion and institutionalization of sociology as a discipline, the question of the scientific status of sociology became less important. Although major methodological differences continued to divide quantitatively oriented sociologists from those in the humanistic tradition, sociology had become too broad to unite under a common method. With the consolidation of the discipline, sociology developed in many directions. The large scale entry of women into sociology in the 1980s inevitably led to different concerns and feminist approaches emerged around new research fields, which on the whole tended to orient sociology in the direction of cultural issues concerning identity, gender, and biographies. The shift from industrial to post industrial societies and the growing impact of globalization have led to a series of shifts in the subject matter of sociology. Without a common method, a cumulative theoretical tradition, the result has been that sociology has been drawn in different directions. While this has led to some weaknesses, it is also a source of strength. Today, sociology has many different approaches which together constitute an influential body of methodologies and theories that have made considerable impact on the wider social and human sciences.

As a discipline acutely aware of the overall reality of society and the historical context, sociology has been more versatile than many sciences. This has been especially the case with regard to the ‘‘cultural turn’’ of which postmodernism has been one expression. Sociologists have been very prominent in developing new frameworks that have greatly advanced the scientific understanding of the social world. One only has to consider the influence of sociologists such as Ulrich Beck on the idea of the risk society, Pierre Bourdieu on the habitus and the forms of capital, Anthony Giddens on structure and agency, Jurgen Habermas on modernity and the theory of communicative action, Edward Soja on space, Bruno Latour on science and technology, Niklas Luhmann on systems theory, Manuel Castells on the information society, Roland Robertson on globalization, and Bryan Turner on citizenship. Sociology, in particular social theory, played a leading role in the reorientation of human geography around space. Much of urban geography today is simply the rediscovery of sociological approaches to the city. The shift in anthropology from the study of primitive societies to modern western societies has made it more or less indistinguishable from sociology. Anthropology, which enjoyed greater prestige in the past, has suffered a far greater crisis in its self understanding than sociology. In this context the rise of cultural and contemporary history as well as cultural studies can be mentioned as relatively new inter disciplinary subject areas that have been closely linked to sociology.

This, however, comes at a price. Much of sociology today is outside of sociology. As sociology becomes more specialized on the one side, and on the other more influential, the result is that it easily loses a specific identity. Thus, the sociology of crime has influenced criminology where most specialized research on crime now occurs and which is not essentially sociological but interdisciplinary. Norbert Elias in 1970 complained of ‘‘pseudo specialization’’ and the retreat of sociologists into sub areas; but he noted what was occurring in sociology was something that had already happened in other disciplines. It would only be a matter of time, he wrote, before the ‘‘fortress will be complete, the drawbridges raised.’’ Like many continental European sociologists, Elias held to the Comtean vision of sociology having the distinctive feature of a general science. Despite Elias’s resistance to specialization, sociology did undergo specialization and it may be suggested that social theory took over the general conception of sociology (Delanty 2005b). But the resulting kind of specialization that sociology underwent led to fears that sociology cannot in fact be a specialized science, since what it does is merely to open up the ground for specialized interdisciplinary areas elsewhere. Thus, specialized sociological research occurs only outside the actual discipline – it is a question of sociologists without sociology. While some see this as the end of sociology, others see it as a new opportunity for a post disciplinary sociology, which should not retreat into the false security of a discipline. John Urry (1981), for instance, argues that sociology does not have a specific disciplinary area in terms of a method or subject matter and it has often been (and necessarily so) ‘‘parasitic’’ on other sciences. Consequently, it should cease to think of itself as a science of society and enter the diffuse territory of post disciplinarity (Urry 2000). This is a contentious position and there have been several recent defenses of sociology, such as the notion of a public sociology advocated by Ben Agger (2000) and Michael Burawoy (2005a, 2005b) and the various attempts of John Scott (2005) and Steve Fuller (2006) to revive the sociological imagination. On the other side, there is a position advocated by John Goldthorpe (2002) that confines sociology to a narrow methodologically grounded science. Is it a choice of ‘‘disciplinary parochialism’’ or ‘‘imperialism,’’ as Andrew Sayer (2000) asks?

As the science of society, sociology has always been a contested inquiry. Many of the major disputes have been about the nature of method and the scope of social science more generally. The debate about the subject matter of sociology has mostly resolved around issues of the know ability of the social world. In recent years an additional challenge has emerged around the very conception of the social (Gane 2004). To a large degree this has been due to major changes in the very definition of society. While much of classical sociology on the whole took society to be the society of the nation state, this is less the case today. It should be pointed out that while the equation of classical sociology with national societies has been exaggerated, there is little doubt that sociology arose as the science of the modern industrial nation state. The comparative tradition in sociological analysis, Weber’s historical sociology, and much of Marxist sociology is a reminder of the global concerns of sociology. However, as an institutionalized social science, sociology has mostly been conducted within national parameters. By far the greatest concentration of sociological research in the second half of the twentieth century has been in the US, where sociology has been the science of social order and national consensus. While the national institutional frameworks continue to be primary in terms of professional accreditation, teaching, funding, and research, the global dimension is coming more to the fore. Inter national sociological associations such as the International Sociological Association and the European Sociological Association now offer rival contexts for sociological research.

It is true too that much of what might be called global sociology is merely the continuation of the comparative tradition, which can be located within an ‘‘international’’ view of sociology. But this would be to neglect a deeper transformation which is also a reflection of the transformation of the social itself. While many social theorists (e.g., Urry 2000) have argued that the social is in decline and others that the social does not coincide with the notion of society, conceived of a spatially bounded entity, it is evident that notwithstanding some of these far reaching claims the social world is undergoing major transformation and the notion of society is in need of considerable reevaluation (Smelser 1997). Exactly how new such developments are will continue to be debated. A strong case can be made for seeing current developments as part of a long term process of civilizational shifts and transformation in the nature of modernity. It is no longer possible to see the social world merely in terms of national structures impacting on the lives of individuals. Such forces are global and they interact with the local in complex ways. The turn to globality in contemporary sociology is not in any way an invalidation of sociology, even if some of the classical approaches are inadequate for the demands of the present day. Indeed, of all the social and human sciences, sociology – with its rich tradition of theory and methodology – is particularly suited to the current global context. Just one point can be made to highlight the relevance of sociology. If globalization entails the intensification of social relations across the globe, the core concern of sociology with the construction and contestability of the social world has a considerable application and relevance.

This leads directly to the second challenge, the question of disciplinarity. According to the Gulbenkian Commission for the Restructuring of the Social Sciences: “To be sociological is not the exclusive purview of persons called sociologists. It is an obligation of all social scientists” (Mudimbe 1996: 98). Does this mean the end of sociology? Clearly, many have taken this view and see sociology disappearing into new inter disciplinary areas and that it can no longer command disciplinary specialization due to its highly general nature. This is too pessimistic, since the Gulbenkian Commission report also points out that the same situation applies to other sciences: history is not the exclusive domain of historians and economic issues are not the exclusive purview of economists. In the era of growing interdisciplinarity, sociology is not alone in having to reorient itself beyond the narrow confines of disciplinarity. Political scientists hardly have a monopoly over politics. Sociology now exists in part within other disciplines, in particular in new post disciplinary areas which it helped to create, but it also exists in its own terms as a post disciplinary social science. In the present day it is evident that sociology takes disciplinary, interdisciplinary, and post disciplinary forms.

While much of sociology has migrated from sociology to the other sciences, sociology today is also increasingly absorbing influences from other sciences. A survey of the discipline’s most influential works noted that a large number have been written by non sociologists (Clawson 1998). This is nothing new: from the very beginning sociology incorporated other disciplines into itself. Of course, this is not without contestation, as in the debate about the influence of cultural studies – itself partly a creation of sociology – on sociology (Rojek & Turner 2001). Sociology is well positioned to engage with other sciences and much of modern sociology has been based on a view of sociology as a science that incorporates the specialized results of other sciences into its framework. As Fuller (2006) argues, today this engagement with other sciences must include biology, which can now explain much of social life. Sociology must engage with some of the claims of biology to explain the social world and offer different accounts. In this respect, then, interdisciplinarity and post disciplinarity need not be seen as the end of a sociology, but a window of opportunity for sociology to address new issues.

One such issue is the public function of sociology. The specialization of sociological research by professional sociology has led to a marginalization of its public role. Michael Burawoy argued this in his presidential address to the ASA in 2004 and opened up a major debate on the future of sociology (Burawoy 2005a, 2005b; Calhoun 2005). Public sociology and professional sociology have become divorced and need to be reconnected, he argues. Public sociology concerns in part bringing professional society to wider publics and in shaping public debates and it may lead to a reorientation in professional sociology as new issues arise. However, as Burawoy argues, there is no public sociology without a professional sociology that supplies it with tested methods and theoretical approaches, conceptual frameworks, and accumulated bodies of knowledge. Public sociology is close to policy relevant sociology, which is a more specific application of sociology to problems set by the state and other public bodies. Public sociology is wider and more discursive and takes place in the public sphere. Burawoy also clarifies the distinction between public and critical sociology. The latter concerns a mode of self reflection on professional sociology and is largely conducted for the benefit of sociology, in contrast to public sociology. Critical sociology has a normative role to play for the discipline. While critical and professional sociology exist for peers, public and policy sociology exist for wider audiences. Of course, many of these roles overlap, as is apparent in the connection between critical and public sociology.

According to many views, one of the functions of sociology is to raise social self understanding. Adorno (2000), for instance, held that while sociology may be the study of society in some general sense, society as such is not a given or a clearly defined domain that can be reduced to a set of ‘‘social facts’’ in Durkheim’s sense. Rather, society consists of different processes and conflicting interpretations. Sociology might be defined in terms of the critical analysis of these discourses in a way that facilitates wider public self reflection. This is a view of sociology reiterated by Mills (1970) and Habermas (1978). In different ways it is present in Scott’s (2005) and Fuller’s (2006) cautious defense of a disciplinary sociology. This means that sociology must be relevant; it must be able to address major public issues (Agger 2000). Inescapably, this means sociology must be able to ask big questions. The success of sociology until now has been in no small part due to its undoubted capacity to address major questions, in particular those that pertain to everyday life.

These are false dilemmas, despite the fact that there are major challenges to be faced. Interdisciplinarity is unavoidable today for all the sciences, but it does not have to mean the disappearance of sociology any more than any other discipline. It is also difficult to draw the conclusion that sociology exists only in a post disciplinary context. However, it is evident that sociology cannot retreat into the classical mold of a general science. Sociology is a versatile and resilient discipline that takes many forms. One of its enduring characteristics is that it brings to bear on the study of the social world a general perspective born of the recognition that the sum is greater than the parts.

References:

- Abraham, J. H. (Ed.) (1973) Origins and Growth of Sociology. Penguin, London.

- Adorno, T. W. (2000) Introduction to Sociology. Sage, London.

- Adorno, T. W. et al. (1976) The Positivist Dispute in German Sociology. Heinemann, London.

- Agger, B. (2000) Public Sociology. Rowman & Littlefield, New York.

- Berger, P. (1966) Invitation to Sociology: A Humanistic Approach. Penguin, London.

- Berger, P. & Luckmann, T. (1967) The Social Con struction of Reality. Penguin, London.

- Bourdieu, P. & Wacquant, L. (1992) An Invitation to Reflexive Sociology. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

- Burawoy, M. (2005a) For Public Sociology. American Sociological Review 70(1): 4 28.

- Burawoy, M. (2005b) The Return of the Repressed: Recovering the Public Face of US Sociology, One Hundred Years On. Annals of the American Academy 600 ( July): 68 85.

- Calhoun, C. (2005) The Promise of Public Sociology. British Journal of Sociology 56(3): 355 63.

- Calhoun, C., Rojek, C., & Turner, B. (Eds.) (2005) Handbook of Sociology. Sage, London.

- Clawson, D. (Ed.) (1998) Required Reading: Sociology’s Most Influential Books. University of Massachusetts Press, Amherest.

- Cole, S. (Ed.) (2001) What Went Wrong With Sociology? Transaction, New Brunswick, NJ.

- Delanty, G. (2005a) Social Science: Philosophical and Methodological Foundations, 2nd edn. Open University Press, Buckingham.

- Delanty, G. (Ed.) (2005b) Handbook of Contemoporary European Social Theory. Routledge, London.

- Durkheim, E. (1982) Rules of the Sociological Method. Macmillan, London.

- Fuller, S. (1998) Divining the Future of Social Theory: From Theology to Rhetoric via Social Epistemology. European Journal of Social Theory 1(1): 107 26.

- Fuller, S. (2006) The New Sociological Imagination. Sage, London.

- Gane, N. (Ed.) (2004) The Futures of Social Theory. Continuum, New York.

- Giddens, A. (1996) In Defence of Sociology. Polity Press, Cambridge.

- Goldthorpe, J. (2002) On Sociology. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Gouldner, A. (1970) The Coming Crisis of Western Sociology. Basic Books, New York.

- Habermas, J. (1978) Knowledge and Human Interests, 2nd edn. Heinemann, London.

- Horowitz, I. (1993) The Decomposition of Sociology. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Lepenies, W. (1988) Between Literature and Science: The Rise of Sociology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Levine, D. (1995) Visions of the Sociological Tradition. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

- Lynd, R. (1939) Knowledge for What? The Place of Social Science in American Culture. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

- Mills, C. W. (1970 [1959]) The Sociological Imagination. Penguin, London.

- Mundimbe, V. Y. (Ed.) (1996) Open the Social Sciences: Report of the Gulbenkian Commission on the Restructuring of the Social Sciences. Stanford University Press, Stanford.

- Parsons, P. (1949) The Structure of Social Action. Free Press, New York.

- Rojek, C. & Turner, B. (2001) Decorative Sociology: Towards a Critique of the Cultural Turn. Socio logical Review 48: 629 48.

- Sayer, A. (2000) For Postdisciplinary Studies: Sociology and the Curse of Disciplinary Parochialism and Imperialism. In: Eldridge, J. et al. (Eds.), For Sociology. Sociology Press, Durham.

- Scott, J. (2005) Sociology and its Others: Reflections on Disciplinary Specialization and Fragmentation. Sociological Research On Line 10 (1).

- Shilling, C. & Mellor, P. (2001) The Sociological Ambition. Sage, London.

- Smelser, N. J. (1997) Problematics of Sociology. University of California Press, Berkeley.

- Strydom, P. (2000) Discourse and Knowledge: The Making of Enlightenment Sociology. Liverpool University Press, Liverpool.

- Urry, J. (1981) Sociology as a Parasite: Some Vices and Virtues. In: Abrams, P.et al. (Eds.), Practice and Progress: British Sociology, 1950 1980. Allen & Unwin, London.

- Urry, J. (2000) Sociology Beyond Societies. Routledge, London.

- Weber, M. (1949 [1904 5]) Objectivity in Social Science and Social Policy. In: The Methodology of the Social Sciences. Free Press, Glencoe, IL.

- Weber, M. (1970) Science as a Vocation. In: Gerth, H. & Mills, C. W. (Eds.), From Max Weber. Routledge & Kegan Paul, London.

Quality of Life Research Paper

This sample sociology research paper on Quality of Life features: 5800 words (approx. 19 pages) and a bibliography with 37 sources. Browse other research paper examples for more inspiration. If you need a thorough research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our custom writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

As a fairly new interdisciplinary field of inquiry, the quality-of-life research has benefited greatly from the discipline of sociology. The field consists of five overlapping traditions: (1) social indicators research, (2) happiness studies, (3) gerontology of successful aging, (4) psychology of well-being, and (5) health-related quality-of-life research. The efforts of sociologists are particularly prominent in the first two of these traditions. Quality of life is also a major issue in the fields of the sociology of work and the sociology of the family.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% off with 24start discount code.

Quality of life has always been a topic of interest in philosophy, where quality of life or the good life is viewed as a virtuous life. The philosophical approach is speculative and tends to be based on the philosopher’s personal experiences in life. In the late twentieth century, however, quality of life became a topic of interest in the social sciences. Social scientists deal in a more empirical way with the subject and systematically gather data on the experiences of other people. In 1995, social scientific quality-of-life research became institutionalized with the founding of the International Society for Quality of Life Studies.

The theme of quality of life developed almost simultaneously in several fields of the social sciences. In sociology, quality of life was often an implicit theme in sociographic studies, such as the portraits of rural life in the United States conducted by Ogburn (1946). Quality of life became the main issue in the “social indicators research” that emerged in the 1960s as a reaction against the domination of economic indicators in the policy process. Initially, the emphasis was on “objective” indicators of well-being, such as poverty, sickness, and suicide; subjective indicators were added during the 1970s.

Landmark books in the latter tradition are Social Indicators of Well-Being: Americans’ Perceptions of Life Quality by Andrews and Withey (1976) and The Quality of American Life: Perceptions, Evaluations and Satisfactions by Campbell, Converse, and Rodgers (1981). Perceived quality of life is now a central issue in social reports in most developed countries, and items on that matter are standard in periodical social surveys. Quality of life has also become an area of interest within the sociology of work, the sociology of housing, and family sociology (Ferriss 2004; Schuessler and Fisher 1985).

In psychology, the first quality-of-life studies were conducted as a part of research into “successful aging.” A typical book of this kind is Personal Adjustment in Old Age by Cavan et al. (1949). In the 1960s, the topic also appeared in studies of mental health, such as Americans View Their Mental Health: A Nationwide Interview Survey by Gurin, Veroff, and Feld (1960) and the groundbreaking crossnational study on The Pattern of Human Concerns by Cantril (1965). Subjective quality of life is now a common issue in psychological research and is often referred to as “subjective well-being” (Diener et al. 1999).

In the 1980s, quality-of-life issues also began to appear in medical research with a focus on patient perceptions of their condition. Typically measured using standard questionnaires such as the Lancaster Quality-of-Life Inventory developed by Lehman (1988), this area of inquiry has focused on “health-related quality of life” and “patient-reported outcomes.” Other medically related quality-of-life studies include residential care (e.g., Clark and Bowling 1990) and handicapped persons (e.g., Schalock 1997).

In the 1990s, quality of life also became an issue in economy. An early analyst in this area was Bernard VanPraag, who summarized much of his work in Happiness Quantified: A Satisfaction Calculus Approach (2004). Another recent account is Happiness and Economics by Bruno Frey and Alois Stutzer (2002).

Social Roots

Quality-of-life research has its roots in several social developments. One such development is the rise in the material standard of living and a concomitant reduction in the occurrence of famine and physical illness. The more humans are free of these ills, the less evident ways for further improvement become, and hence scientific research on the matter becomes more in demand. Interest in quality of life was also stirred by the rise of individualism. The more choices are available, the more interested people become in quality-of-life issues and alternative ways of living. Ideologically, this orientation is manifested in a revival of utilitarian moral philosophy, in which happiness is the central goal (Bentham 1789).

When the postwar economic boom of the 1960s was followed by disenchantment with economic growth, a common slogan of that time was “more well-being rather than more wealth,” and this raised questions of what wellbeing actually is and how it can be furthered. This period of time also witnessed disenchantment with medical technology and a related call for more quality of life rather than mere extension of life. Much of this criticism was voiced by the patient organizations that developed around this time. Health-related quality-of-life research was also furthered by the movement toward “evidence-based” treatment in healthcare that began to come into force during the 1980s. Quality of life was soon seen as a relevant side effect of cure and as a major outcome of care.

Consequently, quality of life became one of the indicators in systematic research into the effects of drugs and treatment protocols.

Concepts of Quality of Life

All social science deals with quality of life in some way. Sociological subjects such as income, power, and prestige can be seen as qualities, and this is also true for psychological subjects such as intelligence and mental health. The crux of quality-of-life research is its inclusiveness; quality-of-life research is not about specific qualities of life but about overall quality. The concept is typically used to strike a balance and designate the desired overall outcome of policies and programs (Schuessler and Fisher 1985:129).

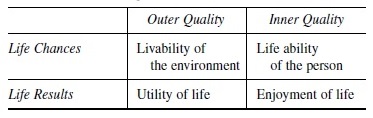

In practice, the term quality of life is used for different notions of the good life. For the most part, quality of life denotes bunches of qualities of life, bunches that can be ordered on the basis of two distinctions. The first distinction is between opportunities for a good life and the outcomes of life. This distinction is quite common in the field of public health research. Preconditions for good health, such as adequate nutrition and professional care, are seldom mixed up with health itself. A second difference is between external and inner qualities. In the first case, the quality is in the environment; in the latter, it is in the individual. This distinction is also quite common in public health. External pathogens are distinguished from inner afflictions. The combination of these two dichotomies yields a fourfold matrix, as shown in Scheme 1.

In the upper half of the scheme, we see next to the outer opportunities in one’s environment, the inner capacities required to exploit these. The environmental conditions can be denoted by the term livability and the personal capacities by the term life ability. This difference is not new. In sociology, the distinction between “social capital” and “psychological capital” is sometimes used in this context, and in the psychology of stress the difference is labeled negatively in terms of “burden” and “bearing power.”

The lower half of the scheme is about the quality of life with respect to its outcomes. These outcomes can be judged by their value for one’s environment and by their value for oneself. The external worth of a life is denoted by the term utility of life, the inner valuation of which is called appreciation of life.

Livability of the Environment

The top left quadrant denotes the meaning of good living conditions, or “livability.” One can also speak of the “habitability” of an environment, though that term is also used for the quality of housing (Veenhoven 1996:7–9). Ecologists view livability in the natural environment and describe it in terms of pollution, global warming, and degradation of nature. Currently, livability is typically associated with environmental preservation. On the other hand, city planners see livability in the built environment and associate it with sewerage systems, traffic jams, and ghetto formation. Here, the good life is seen as a fruit of human intervention. In public health, all this is referred to as a “sane” environment.

Society is central in the sociological view. Firstly, livability is associated with the quality of society as a whole. Classic concepts of the “good society” stress material welfare and social equality, sometimes equating the concept more or less with the welfare state. Currently, communitarians emphasize close networks, strong norms, and active voluntary associations; the reverse of this livability concept is “social fragmentation.” Second, livability is seen in one’s position in society. For a long time, the emphasis was on the “underclass,” but currently, attention is shifting to “social exclusion.” In the latter view, quality of life is full participation in society.

Life Ability of the Person

The concept of “life ability” denotes how well people are equipped to cope with the problems of life. The most common depiction of this aspect of quality of life is the absence of functional defects. This is “health” in the limited sense, sometimes referred to as “negative health.” In this context, doctors focus on unimpaired functioning of the body, while psychologists stress the absence of mental defects. This use of words presupposes a “normal” level of functioning. Good quality of life is the body and mind working as designed. This is the common meaning used in curative care.

Next to absence of disease is the excellence of function, or “positive health,” which is associated with energy and resilience. Psychological concepts of positive mental health also involve autonomy, reality control, creativity, and inner synergy of traits and strivings. This broader definition is the favorite of training professions and is central to the “positive psychology” movement.

Utility of Life

The utility of life represents the notion that a good life must be good for something more than itself. When evaluating the external effects of a life, one can consider the utility of life functionality for the environment. In this context, doctors stress how essential a patient’s life is to his or her intimates. At a higher level, quality of life is seen in contributions to society, the contributions an individual can make to human culture. Moralists see quality in the preservation of the moral order and would deem the life of a saint to be better than that of a sinner. In this vein, the quality of a life is also linked to effects on the ecosystem. Ecologists see more quality in a life lived in a “sustainable” manner than in the life of a polluter. Gerson (1976:795) calls this the “transcendentalist” conception of quality of life.

Enjoyment of Life

The final outcome of life for the individual is the subjective appreciation of life. This is the quality of life in the eye of the beholder, commonly referred to by terms such as subjective well-being, life satisfaction, and happiness in a limited sense of the word.

Humans are capable of evaluating their life in different ways. Like other higher animals, we have an ability to appraise our situation affectively. We feel good or bad about particular things and our mood level signals overall adaptation. These affective appraisals are automatic, but unlike other animals, humans can reflect on this experience. Humans also have a sense of how they have felt in the past. Humans can judge life cognitively by comparing their experience with notions of how it should be.

Measures of Quality of Life

Quality-of-life research is primarily about measurement. Hence, the field can be aptly described by the measures used, of which there are many. In the following sections, examples of measures used in quality-of-life research are presented. The substantive dimensions these measures are thought to represent will be brought to light using the Scheme 1 classification.

Meanings in Multidimensional Measures of Quality of Life

Most of these measures are multidimensional and assess different qualities of life, which are aggregated in one “quality-of-life score. ” Often, the different qualities are also presented separately in a “quality-of-life profile. ” Multidimensional measures figure in medical quality-oflife research, gerontological research on “successful aging,” psychological “well-being” research, sociologically oriented research on individual “welfare,” and comparative studies on quality of life in nations.

Example of a Medical Quality-of-Life Index

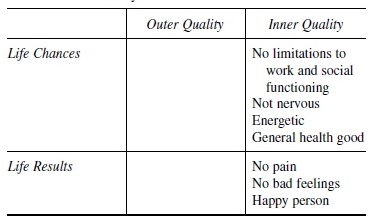

One of the most common measures used in healthrelated quality-of-life research is the SF-36 Health Survey (Ware 1996). It is a questionnaire on topics on physical limitations in daily chores (10 items), physical limitations to work performance (4 items), bodily pain (2 items), perceived general health (6 items), vitality (4 items), physical and/or emotional limitations to social functioning (2 items), emotional limitations to work performance (3 items), self-characterizations as nervous (1 item), and recent enjoyment of life (4 items). Scheme 2 shows how these topics fit the above classification of qualities of life. Most elements of this scale refer to performance potential and belong in the life-ability quadrant top right. This is not surprising, since the scale is aimed explicitly at health. Still, some of the items concern outcomes rather than potency, in particular the items on recent enjoyment of life (last on the list). As a proper health measure, the SF-36 does not involve outer qualities. So the left quadrants in Scheme 2 remain empty.

Several other medical measures of quality of life involve items about environmental conditions that belong in the livability quadrant. For instance, the Quality of Life Interview Schedule by Ouelette-Kuntz (1990) involves items such as availability of services for handicapped persons. In this supply-centered measure of the good life, life is better the more services are offered and the more greedily they are used. Likewise, the quality-of-life index for cancer patients (Spitzer et al. 1981) lists support by family and friends as a quality criterion. Some medical indexes also include outer effects that belong to the utility quadrant. Some typical items are continuation of work tasks and support provided to intimates and fellow patients.

Example of a Sociological Welfare Index

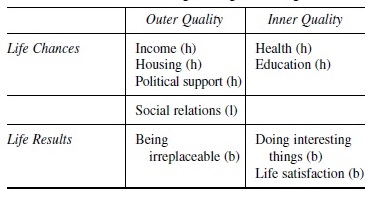

Similar indexes have been developed in sociology, mostly in the context of marketing research for the welfare state. One of the first attempts to chart quality of life in a general population was the made in the Scandinavian study of comparative welfare under the direction of Erik Allardt (1976). Welfare is measured using the following criteria: income, housing, political support, social relations, being irreplaceable, doing interesting things, health, education, and life satisfaction. Allardt classified these indicators using his, now classic, distinction between “having” (h), “loving” (l), and “being” (b). These indicators can also be ordered in the fourfold matrix shown in Scheme 3. Most of the scale items belong in the top left quadrant because they concern preconditions for a good life rather than good living as such and because these chances are in the environment rather than in the individual. This is the case with income, housing, political support, and social relations. Two further items also denote chances, but they are internal capabilities. These are the health factor and the level of education. These items are placed in the top right quadrant of personal life ability. The item “being irreplaceable” belongs in the utility bottom left quadrant. It denotes a value of life to others. The last two items belong in the enjoyment bottom right quadrant. “Doing interesting things” denotes appreciation of an aspect of life, while life satisfaction concerns appreciation of life as a whole.

Example of an Index of Quality of Life in Nations

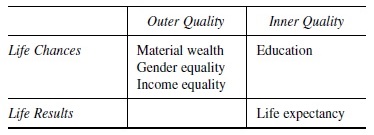

In addition to the measures for comparing quality of life within nations, there are also multidimensional measures for comparing quality of life across nations. These measures are typically meant as an alternative to the common economic metric for quality of life—that is, gross national product per head. They all offer something more but differ in the mix of additions. The most commonly used indicator in this field is the Human Development Index (HDI). This index was developed for the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), which describes the progress in all countries of the world in its annual Human Development Reports (UNDP 1990). The HDI is the major yardstick used in these reports. The basic variant of this measure involves three items: (1) material wealth, measured by buying power per head; (2) education, as measured by literacy and schooling; and (3) life expectancy at birth. Later variants of the HDI involve further items, such as gender equality, measured using the Gender Empowerment Index, which involves male-female ratios in literacy, school enrollment, and income. In a theoretical account of this measure, the UNDP states that the focus should be on how development enlarges people’s choice and, thereby, their chances for leading long, healthy, and creative lives (p. 9).

As shown in Scheme 4, this index covers three meanings. First, it is about living conditions: in the basic index material, affluence in society and in the variants, the degree of social equality. These items belong in the top left quadrant. Second, the HDI includes average educational level, which belongs in the top right quadrant. The item “life expectancy” is an outcome variable and belongs right below. The bottom left quadrant remains empty since the UNDP’s measure of development does not involve indicators of utility of life.

Extended variants in this family provide more illustration. For instance, Naroll’s (1984:73) Quality-of-Life Index includes contributions to science by the country, which fits the utility lower left quadrant. This index also includes mental health, which belongs in the life-ability quadrant, top right and suicide, which belongs in the bottom right quadrant.

Strengths and Weaknesses

The power of these indexes is that they summarize the various qualities of life in one number, thereby allowing comparison with others and monitoring over time. Since most of these measures consist of subindexes, they also provide an overview of strong and weak points. Further, these indexes have public appeal; they list things that are typically valued.

Yet there are also weaknesses in this multidimensional measurement approach. One such limitation is that the lists of valued things are never complete but are restricted to a few measurable items. We may value true love and artistic innovations, but these dimensions are not to be captured in numbers. Furthermore, these lists of valued things are time bound and are therefore ill suited for extended periods of monitoring; they reflect how well we are doing with respect to yersterday’s problems.

Typically, all items are treated alike, but the relative importance can differ. Differential weights are used in some cases, but the basis for this is typically weak and does not acknowledge that the importance of living conditions depends on life abilities.

A more basic problem is found in aggregation, in that one cannot meaningfully add environmental opportunities to individual life abilities. It is the fit of opportunities and abilities that counts for quality of life, not the sum. Likewise, it makes no sense to add chances for a good life (top quadrants) and outcomes of life (bottom quadrants), certainly not if one wants to identify the opportunities that are most critical. This lack of a clear meaning reduces the descriptive relevance of these measures and impedes explanation.

Measures for Specific Qualities of Life

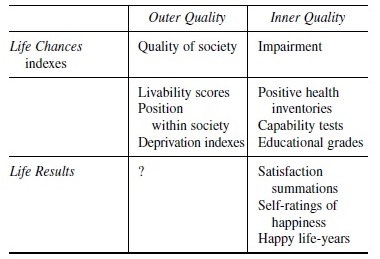

Next to these encompassing measures of quality of life, there are measures that are used to denote specific qualities. These indicators can also be mapped on the matrix. See Scheme 5. Again, some illustrative examples will suffice.

Measures of Livability

Environmental life chances are measured in two ways: (1) by the possibilities embodied in the environment as a whole and (2) by relative access to these opportunities. The former measures concern the livability of societies, such as nations or cities. These indicators are typically used in developmental policy. The latter are about the relative advantage or deprivations of persons in these contexts and are rooted mostly in the politics of redistribution.

Measures of livability of society focus on nations; an illustrative example is Estes’s (1984) Index of Social Progress. This measure involves aspects such as wealth of the nation, peace with neighbors, internal stability, and democracy. There are similar measures for quality of life in cities and regions. There are also livability counts for institutions such as army bases, prisons, hospitals for the mentally ill, and residences for the elderly.

Measures of relative deprivation focus on differences among citizens with regard to, for instance, income, work, and social contacts. Differences in the command of these resources are typically interpreted as differential access to scarce resources. All these measures work with a points system and summate scores based on different criteria in some way.

These inventories have the same limitations as multidimensional measures of better quality of life, but one problem specific to the measurement of livability is in the implicit theories behind the measure. The ingredients of these indexes are things believed to add to the livability of the environment, but these beliefs are not necessarily rooted in knowledge of what people really need. In this respect, measures of the livability of the social environment differ from the indicators used for the physical environment. On the basis of much research, we can now estimate fairly well how certain pollutants will affect illness and longevity. However, a similar evidence base is largely lacking for the livability of social environments, leaving a vacuum that is typically filled with ideological prepossession. As a result, there is some circularity in the use of these measures; although they are meant to show policymakers the way to the good life, they draw heavily on what policymakers believe to be a good life.

Measures of Life Ability

Different measures exist to assess “capabilities for living.” First, there is a rich tradition of health measurement in the healing professions.

Measures of health are, for the greater part, measures of negative health. There are various inventories of afflictions and functional limitations, several of which combine physical and mental impairment scores. Assessment is based on functional tests, expert ratings, and self-reports. There also are self-report inventories for positive health in the tradition of personality assessment (e.g., Ryff and Keyes 1995). This links up with a second tradition of capability measurement—that is, psychological “testing” for selection in education and at work.

As in the case of livability, these measures do not provide a complete estimate of life ability. Again, we meet the same fundamental limitations of completeness and aggregation. Unlike the case of livability, there is some validation testing in this field. Intelligence tests, in particular, are gauged by their predictive value for success at school and at work. Yet many of the other ability tests lack validation.

Measures for Utility of Life

There are many criteria for evaluating the usefulness of a life, of which only a few can be quantified. When evaluating the utility of a person’s life by the contribution that life makes to society, one aspect is good citizenship as measured by law abidance and voluntary work. Where the utility of a life is measured with its effect on the environment, consumption is a relevant aspect and there are several measures of “green living.” For some criteria, we have better information at the aggregate level. Wackernagel et al.’s (1999) ecological footprint measures how much land and water area is used to produce what we consume. Patent counts per country give an idea of the contribution to human progress and are part of Naroll’s (1984) index.

Measures of Appreciation of Life

Measurement of the subjective appraisal of life is relatively straightforward. Interviews are conducted through direct questioning, such as an interview or a questionnaire. Since the focus is on “how much” the respondent enjoys life rather than “why,” the qualitative interview method is limited in this field. Most assessments are self-reports in response to standard questions with fixed-response options.

Many of these measures concern specific appraisals, such as satisfaction with one’s sex life or perceived meaning of life. As in the case of life chances, these aspects cannot be meaningfully added in a whole, because satisfactions cannot be assessed exhaustively and differ in significance. Yet humans are also capable of overall appraisals. As noted earlier, we can estimate how well we feel generally and report on that. So encompassing measurement is possible in this quality quadrant.

There are various ways to ask people how much they enjoy their life as a whole. One way is to ask them repeatedly how much they enjoy it right now and to average the responses. This is called “experience sampling.” This method has many advantages, but it is expensive. The other way is to ask respondents to estimate how well they feel generally or to strike the balance of their life. This is common practice, and all the questions ever used for this purpose are stored in the Item Bank of the World Database of Happiness , a continuous register of scientific research on subjective enjoyment of life, kept at Erasmus University, Rotterdam in the Netherlands (http://www. worlddatabaseofhappiness.eur.nl).

There are doubts about the value of these self-reports, in particular about interpretation of questions, honesty of answers, and interpersonal comparability. Empirical studies, however, show reasonable validity and reliability. There are also qualms about comparability of average responses across cultures; it is claimed that questions are differently understood and that response bias differs systematically in countries. These objections have also been checked empirically and appeared to carry no weight. This literature is aptly summarized in Diener et al. (1999) and Schyns (2003).

Questions on enjoyment of life typically concern the current time. Most questions refer to happiness “these days” or “over the last year.” Obviously, the good life requires more than this, hence happiness must also be assessed over longer periods. In several contexts, we must know happiness over a lifetime or, better, how long people live happily. At the individual level, it is mostly difficult to assess how long and happily people live, because we can know that only when they are dead; however, at the population level, the average number of years lived happily can be estimated by combining average happiness with life expectancy. For details of this method, see Veenhoven (1996).

The magnitude of insight these quality-of-life measures provide is somewhat difficult to assess, simply because they measure too many different aspects of life. However, happiness provides a fairly inclusive output measure, especially when combined with life expectancy in happy lifeyears (HLY). For this reason, the next section summarizes the main results obtained with this indicator of quality of life.

Sociology of Happiness

Sociologists have studied happiness at two levels, at the macro level for comparing across nations and at the micro level for identifying differences within nations.

Happiness and Society

Comparative research on happiness started in the 1960s with Cantril’s (1965) global study on “the pattern of human concern.” Happiness is now a common item in international survey programs such as the World Values Survey. The standard question on life satisfaction is as follows:

Taking all together, how satisfied or dissatisfied are you currently with your life as a whole?

In the year 2005, comparable data were available for 90 nations. In the following, I offer some insights into what these data suggest about the quality of life in contemporary societies.

Level of Happiness in Nations

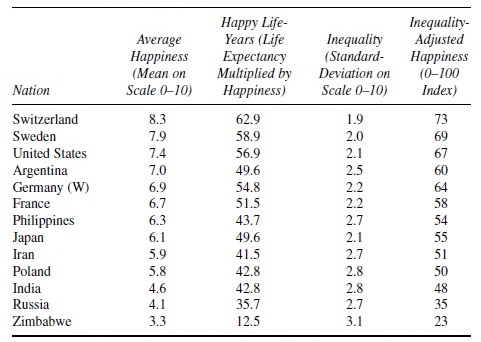

Most research has focused on average happiness, finding sizable and consistent differences across nations (see Diener and Suh 2000). As shown in Table 1, average happiness is above neutral in most countries, meaning that great happiness for a great number is possible. However, for Russia and for most former Soviet states, the average score is less than 5. Average happiness is also low in several African countries.

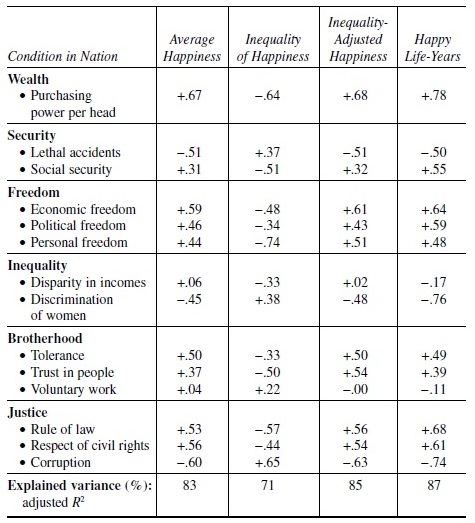

There is a system in these differences. People live more happily in rich nations than in poor ones and happiness is also higher in nations characterized by rule of law, freedom, good governance, and modernity. However, happiness is not related to everything deemed desirable. Income inequality in nations appears to be unrelated to average happiness, though it does accompany some inequality of happiness, as shown for 90 nations in the 1990s and presented in Table 2.

There is considerable interrelation between the societal characteristics. The most affluent nations are also the freest and the most modern. It is therefore difficult to estimate the effect of each of these variables separately. The correlations are much abated when level of income is controlled, and the correlation with social security turns negative. Still, with the exception of income inequality, sizable correlations remain. Whatever their relative contribution, these variables explain 83 percent of the differences in average happiness across nations.

Trend data on average happiness are available for the United States from 1945, for Japan from 1958, and for the first eight member states of the European Union (EU) from 1973. These data show that happiness rose somewhat in the United States and the EU but stagnated in Japan.

These findings do not fit the common theory that happiness depends on social comparison. Since people compare with compatriots in the first place, this would imply little difference across nations and no change over time. Nor do the findings fit the theory that happiness is a fixed mental trait; if so, there would not be such strong correlations with societal qualities or any change over time. The findings fit best with the livability theory of happiness, which holds that happiness depends on the gratification of innate human needs and that not all societies meet human needs equally well (Veenhoven 1995). Another noteworthy implication of the above findings is that modern society does not score as low in livability as much of problem-focused sociology suggests.