Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is Peer Review? | Types & Examples

What Is Peer Review? | Types & Examples

Published on December 17, 2021 by Tegan George . Revised on June 22, 2023.

Peer review, sometimes referred to as refereeing , is the process of evaluating submissions to an academic journal. Using strict criteria, a panel of reviewers in the same subject area decides whether to accept each submission for publication.

Peer-reviewed articles are considered a highly credible source due to the stringent process they go through before publication.

There are various types of peer review. The main difference between them is to what extent the authors, reviewers, and editors know each other’s identities. The most common types are:

- Single-blind review

- Double-blind review

- Triple-blind review

Collaborative review

Open review.

Relatedly, peer assessment is a process where your peers provide you with feedback on something you’ve written, based on a set of criteria or benchmarks from an instructor. They then give constructive feedback, compliments, or guidance to help you improve your draft.

Table of contents

What is the purpose of peer review, types of peer review, the peer review process, providing feedback to your peers, peer review example, advantages of peer review, criticisms of peer review, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about peer reviews.

Many academic fields use peer review, largely to determine whether a manuscript is suitable for publication. Peer review enhances the credibility of the manuscript. For this reason, academic journals are among the most credible sources you can refer to.

However, peer review is also common in non-academic settings. The United Nations, the European Union, and many individual nations use peer review to evaluate grant applications. It is also widely used in medical and health-related fields as a teaching or quality-of-care measure.

Peer assessment is often used in the classroom as a pedagogical tool. Both receiving feedback and providing it are thought to enhance the learning process, helping students think critically and collaboratively.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Depending on the journal, there are several types of peer review.

Single-blind peer review

The most common type of peer review is single-blind (or single anonymized) review . Here, the names of the reviewers are not known by the author.

While this gives the reviewers the ability to give feedback without the possibility of interference from the author, there has been substantial criticism of this method in the last few years. Many argue that single-blind reviewing can lead to poaching or intellectual theft or that anonymized comments cause reviewers to be too harsh.

Double-blind peer review

In double-blind (or double anonymized) review , both the author and the reviewers are anonymous.

Arguments for double-blind review highlight that this mitigates any risk of prejudice on the side of the reviewer, while protecting the nature of the process. In theory, it also leads to manuscripts being published on merit rather than on the reputation of the author.

Triple-blind peer review

While triple-blind (or triple anonymized) review —where the identities of the author, reviewers, and editors are all anonymized—does exist, it is difficult to carry out in practice.

Proponents of adopting triple-blind review for journal submissions argue that it minimizes potential conflicts of interest and biases. However, ensuring anonymity is logistically challenging, and current editing software is not always able to fully anonymize everyone involved in the process.

In collaborative review , authors and reviewers interact with each other directly throughout the process. However, the identity of the reviewer is not known to the author. This gives all parties the opportunity to resolve any inconsistencies or contradictions in real time, and provides them a rich forum for discussion. It can mitigate the need for multiple rounds of editing and minimize back-and-forth.

Collaborative review can be time- and resource-intensive for the journal, however. For these collaborations to occur, there has to be a set system in place, often a technological platform, with staff monitoring and fixing any bugs or glitches.

Lastly, in open review , all parties know each other’s identities throughout the process. Often, open review can also include feedback from a larger audience, such as an online forum, or reviewer feedback included as part of the final published product.

While many argue that greater transparency prevents plagiarism or unnecessary harshness, there is also concern about the quality of future scholarship if reviewers feel they have to censor their comments.

In general, the peer review process includes the following steps:

- First, the author submits the manuscript to the editor.

- Reject the manuscript and send it back to the author, or

- Send it onward to the selected peer reviewer(s)

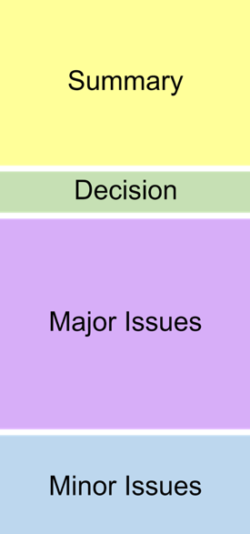

- Next, the peer review process occurs. The reviewer provides feedback, addressing any major or minor issues with the manuscript, and gives their advice regarding what edits should be made.

- Lastly, the edited manuscript is sent back to the author. They input the edits and resubmit it to the editor for publication.

In an effort to be transparent, many journals are now disclosing who reviewed each article in the published product. There are also increasing opportunities for collaboration and feedback, with some journals allowing open communication between reviewers and authors.

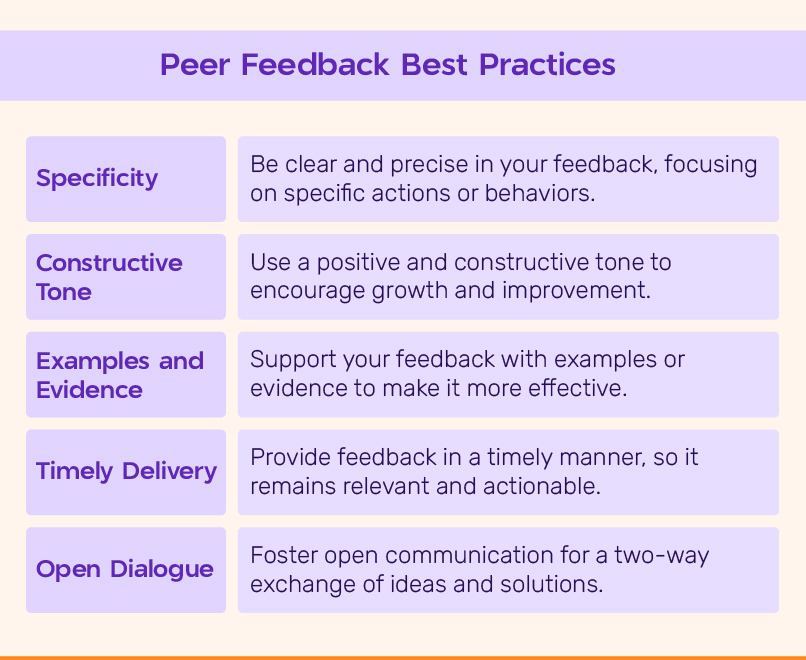

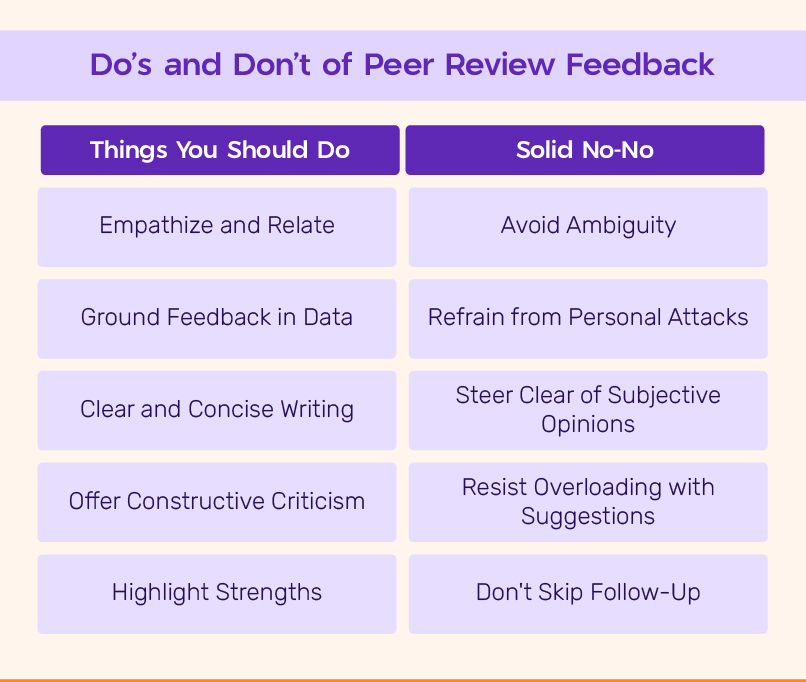

It can seem daunting at first to conduct a peer review or peer assessment. If you’re not sure where to start, there are several best practices you can use.

Summarize the argument in your own words

Summarizing the main argument helps the author see how their argument is interpreted by readers, and gives you a jumping-off point for providing feedback. If you’re having trouble doing this, it’s a sign that the argument needs to be clearer, more concise, or worded differently.

If the author sees that you’ve interpreted their argument differently than they intended, they have an opportunity to address any misunderstandings when they get the manuscript back.

Separate your feedback into major and minor issues

It can be challenging to keep feedback organized. One strategy is to start out with any major issues and then flow into the more minor points. It’s often helpful to keep your feedback in a numbered list, so the author has concrete points to refer back to.

Major issues typically consist of any problems with the style, flow, or key points of the manuscript. Minor issues include spelling errors, citation errors, or other smaller, easy-to-apply feedback.

Tip: Try not to focus too much on the minor issues. If the manuscript has a lot of typos, consider making a note that the author should address spelling and grammar issues, rather than going through and fixing each one.

The best feedback you can provide is anything that helps them strengthen their argument or resolve major stylistic issues.

Give the type of feedback that you would like to receive

No one likes being criticized, and it can be difficult to give honest feedback without sounding overly harsh or critical. One strategy you can use here is the “compliment sandwich,” where you “sandwich” your constructive criticism between two compliments.

Be sure you are giving concrete, actionable feedback that will help the author submit a successful final draft. While you shouldn’t tell them exactly what they should do, your feedback should help them resolve any issues they may have overlooked.

As a rule of thumb, your feedback should be:

- Easy to understand

- Constructive

Below is a brief annotated research example. You can view examples of peer feedback by hovering over the highlighted sections.

Influence of phone use on sleep

Studies show that teens from the US are getting less sleep than they were a decade ago (Johnson, 2019) . On average, teens only slept for 6 hours a night in 2021, compared to 8 hours a night in 2011. Johnson mentions several potential causes, such as increased anxiety, changed diets, and increased phone use.

The current study focuses on the effect phone use before bedtime has on the number of hours of sleep teens are getting.

For this study, a sample of 300 teens was recruited using social media, such as Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat. The first week, all teens were allowed to use their phone the way they normally would, in order to obtain a baseline.

The sample was then divided into 3 groups:

- Group 1 was not allowed to use their phone before bedtime.

- Group 2 used their phone for 1 hour before bedtime.

- Group 3 used their phone for 3 hours before bedtime.

All participants were asked to go to sleep around 10 p.m. to control for variation in bedtime . In the morning, their Fitbit showed the number of hours they’d slept. They kept track of these numbers themselves for 1 week.

Two independent t tests were used in order to compare Group 1 and Group 2, and Group 1 and Group 3. The first t test showed no significant difference ( p > .05) between the number of hours for Group 1 ( M = 7.8, SD = 0.6) and Group 2 ( M = 7.0, SD = 0.8). The second t test showed a significant difference ( p < .01) between the average difference for Group 1 ( M = 7.8, SD = 0.6) and Group 3 ( M = 6.1, SD = 1.5).

This shows that teens sleep fewer hours a night if they use their phone for over an hour before bedtime, compared to teens who use their phone for 0 to 1 hours.

Peer review is an established and hallowed process in academia, dating back hundreds of years. It provides various fields of study with metrics, expectations, and guidance to ensure published work is consistent with predetermined standards.

- Protects the quality of published research

Peer review can stop obviously problematic, falsified, or otherwise untrustworthy research from being published. Any content that raises red flags for reviewers can be closely examined in the review stage, preventing plagiarized or duplicated research from being published.

- Gives you access to feedback from experts in your field

Peer review represents an excellent opportunity to get feedback from renowned experts in your field and to improve your writing through their feedback and guidance. Experts with knowledge about your subject matter can give you feedback on both style and content, and they may also suggest avenues for further research that you hadn’t yet considered.

- Helps you identify any weaknesses in your argument

Peer review acts as a first defense, helping you ensure your argument is clear and that there are no gaps, vague terms, or unanswered questions for readers who weren’t involved in the research process. This way, you’ll end up with a more robust, more cohesive article.

While peer review is a widely accepted metric for credibility, it’s not without its drawbacks.

- Reviewer bias

The more transparent double-blind system is not yet very common, which can lead to bias in reviewing. A common criticism is that an excellent paper by a new researcher may be declined, while an objectively lower-quality submission by an established researcher would be accepted.

- Delays in publication

The thoroughness of the peer review process can lead to significant delays in publishing time. Research that was current at the time of submission may not be as current by the time it’s published. There is also high risk of publication bias , where journals are more likely to publish studies with positive findings than studies with negative findings.

- Risk of human error

By its very nature, peer review carries a risk of human error. In particular, falsification often cannot be detected, given that reviewers would have to replicate entire experiments to ensure the validity of results.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Measures of central tendency

- Chi square tests

- Confidence interval

- Quartiles & Quantiles

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Thematic analysis

- Discourse analysis

- Cohort study

- Ethnography

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Conformity bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Availability heuristic

- Attrition bias

- Social desirability bias

Peer review is a process of evaluating submissions to an academic journal. Utilizing rigorous criteria, a panel of reviewers in the same subject area decide whether to accept each submission for publication. For this reason, academic journals are often considered among the most credible sources you can use in a research project– provided that the journal itself is trustworthy and well-regarded.

In general, the peer review process follows the following steps:

- Reject the manuscript and send it back to author, or

- Send it onward to the selected peer reviewer(s)

- Next, the peer review process occurs. The reviewer provides feedback, addressing any major or minor issues with the manuscript, and gives their advice regarding what edits should be made.

- Lastly, the edited manuscript is sent back to the author. They input the edits, and resubmit it to the editor for publication.

Peer review can stop obviously problematic, falsified, or otherwise untrustworthy research from being published. It also represents an excellent opportunity to get feedback from renowned experts in your field. It acts as a first defense, helping you ensure your argument is clear and that there are no gaps, vague terms, or unanswered questions for readers who weren’t involved in the research process.

Peer-reviewed articles are considered a highly credible source due to this stringent process they go through before publication.

Many academic fields use peer review , largely to determine whether a manuscript is suitable for publication. Peer review enhances the credibility of the published manuscript.

However, peer review is also common in non-academic settings. The United Nations, the European Union, and many individual nations use peer review to evaluate grant applications. It is also widely used in medical and health-related fields as a teaching or quality-of-care measure.

A credible source should pass the CRAAP test and follow these guidelines:

- The information should be up to date and current.

- The author and publication should be a trusted authority on the subject you are researching.

- The sources the author cited should be easy to find, clear, and unbiased.

- For a web source, the URL and layout should signify that it is trustworthy.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

George, T. (2023, June 22). What Is Peer Review? | Types & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved September 10, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/peer-review/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, what are credible sources & how to spot them | examples, ethical considerations in research | types & examples, applying the craap test & evaluating sources, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

50 Great Peer Review Examples: Sample Phrases + Scenarios

by Emre Ok March 16, 2024, 10:48 am updated August 8, 2024, 12:19 pm 1.5k Views

Peer review is a concept that has multiple different applications and definitions. Depending on your field, the definition of peer review can change greatly.

In the workplace, the meaning of peer review or peer feedback is that it is simply the input of a peer or colleague on another peer’s performance, attitude, output, or any other performance metric .

While in the academic world peer review’s definition is the examination of an academic paper by another fellow scholar in the field.

Even in the American legal system , people are judged in front of a jury made up of their peers.

It is clear as day that peer feedback carries a lot of weight and power. The input from someone who has the same experience with you day in and day out is on occasion, more meaningful than the feedback from direct reports or feedback from managers .

So here are 50 peer review examples and sample peer feedback phrases that can help you practice peer-to-peer feedback more effectively!

Table of Contents

Peer Feedback Examples: Offering Peers Constructive Criticism

One of the most difficult types of feedback to offer is constructive criticism. Whether you are a chief people officer or a junior employee, offering someone constructive criticism is a tight rope to walk.

When you are offering constructive criticism to a peer? That difficulty level is doubled. People can take constructive criticism from above or below.

One place where criticism can really sting is when it comes from someone at their level. That is why the peer feedback phrases below can certainly be of help.

Below you will find 10 peer review example phrases that offer constructive feedback to peers:

- “I really appreciate the effort you’ve put into this project, especially your attention to detail in the design phase. I wonder if considering alternative approaches to the user interface might enhance user engagement. Perhaps we could explore some user feedback or current trends in UI design to guide us.”

- “Your presentation had some compelling points, particularly the data analysis section. However, I noticed a few instances where the connection between your arguments wasn’t entirely clear. For example, when transitioning from the market analysis to consumer trends, a clearer linkage could help the audience follow your thought process more effectively.”

- “I see you’ve put a lot of work into developing this marketing strategy, and it shows promise. To address the issue with the target demographic, it might be beneficial to integrate more specific market research data. I can share a few resources on market analysis that could provide some valuable insights for this section.”

- “You’ve done an excellent job balancing different aspects of the project, but I think there’s an opportunity to enhance the overall impact by integrating some feedback we received in the last review. For instance, incorporating more user testimonials could strengthen our case study section.”

- “Your report is well-structured and informative. I would suggest revisiting the conclusions section to ensure that it aligns with the data presented earlier. Perhaps adding a summary of key findings before concluding would reinforce the report’s main takeaways.”

- “In reviewing your work, I’m impressed by your analytical skills. I believe using ‘I’ statements could make your argument even stronger, as it would provide a personal perspective that could resonate more with the audience. For example, saying ‘I observed a notable trend…’ instead of ‘There is a notable trend…’ can add a personal touch.”

- “Your project proposal is thought-provoking and innovative. To enhance it further, have you considered asking reflective questions at the end of each section? This could encourage the reader to engage more deeply with the material, fostering a more interactive and thought-provoking dialogue.”

- “I can see the potential in your approach to solving this issue, and I believe with a bit more refinement, it could be very effective. Maybe a bit more focus on the scalability of the solution could highlight its long-term viability, which would be impressive to stakeholders.”

- “I admire the dedication you’ve shown in tackling this challenging project. If you’re open to it, I would be happy to collaborate on some of the more complex aspects, especially the data analysis. Together, we might uncover some additional insights that could enhance our findings.”

- “Your timely submission of the project draft is commendable. To make your work even more impactful, I suggest incorporating recent feedback we received on related projects. This could provide a fresh perspective and potentially uncover aspects we might not have considered.”

Sample Peer Review Phrases: Positive Reinforcement

Offering positive feedback to peers as opposed to constructive criticism is on the easier side when it comes to the feedback spectrum.

There are still questions that linger however, such as: “ How to offer positive feedback professionally? “

To help answer that question and make your life easier when offering positive reinforcements to peers, here are 10 positive peer review examples! Feel free to take any of the peer feedback phrases below and use them in your workplace in the right context!

- “Your ability to distill complex information into easy-to-understand visuals is exceptional. It greatly enhances the clarity of our reports.”

- “Congratulations on surpassing this quarter’s sales targets. Your dedication and strategic approach are truly commendable.”

- “The innovative solution you proposed for our workflow issue was a game-changer. It’s impressive how you think outside the box.”

- “I really appreciate the effort and enthusiasm you bring to our team meetings. It sets a positive tone that encourages everyone.”

- “Your continuous improvement in client engagement has not gone unnoticed. Your approach to understanding and addressing their needs is exemplary.”

- “I’ve noticed significant growth in your project management skills over the past few months. Your ability to keep things on track and communicate effectively is making a big difference.”

- “Thank you for your proactive approach in the recent project. Your foresight in addressing potential issues was key to our success.”

- “Your positive attitude, even when faced with challenges, is inspiring. It helps the team maintain momentum and focus.”

- “Your detailed feedback in the peer review process was incredibly helpful. It’s clear you put a lot of thought into providing meaningful insights.”

- “The way you facilitated the last workshop was outstanding. Your ability to engage and inspire participants sparked some great ideas.”

Peer Review Examples: Feedback Phrases On Skill Development

Peer review examples on talent development are one of the most necessary forms of feedback in the workplace.

Feedback should always serve a purpose. Highlighting areas where a peer can improve their skills is a great use of peer review.

Peers have a unique perspective into each other’s daily life and aspirations and this can quite easily be used to guide each other to fresh avenues of skill development.

So here are 10 peer sample feedback phrases for peers about developing new skillsets at work:

- “Considering your interest in data analysis, I think you’d benefit greatly from the advanced Excel course we have access to. It could really enhance your data visualization skills.”

- “I’ve noticed your enthusiasm for graphic design. Setting a goal to master a new design tool each quarter could significantly expand your creative toolkit.”

- “Your potential in project management is evident. How about we pair you with a senior project manager for a mentorship? It could be a great way to refine your skills.”

- “I came across an online course on persuasive communication that seems like a perfect fit for you. It could really elevate your presentation skills.”

- “Your technical skills are a strong asset to the team. To take it to the next level, how about leading a workshop to share your knowledge? It could be a great way to develop your leadership skills.”

- “I think you have a knack for writing. Why not take on the challenge of contributing to our monthly newsletter? It would be a great way to hone your writing skills.”

- “Your progress in learning the new software has been impressive. Continuing to build on this momentum will make you a go-to expert in our team.”

- “Given your interest in market research, I’d recommend diving into analytics. Understanding data trends could provide valuable insights for our strategy discussions.”

- “You have a good eye for design. Participating in a collaborative project with our design team could offer a deeper understanding and hands-on experience.”

- “Your ability to resolve customer issues is commendable. Enhancing your conflict resolution skills could make you even more effective in these situations.”

Peer Review Phrase Examples: Goals And Achievements

Equally important as peer review and feedback is peer recognition . Being recognized and appreciated by one’s peers at work is one of the best sentiments someone can experience at work.

Peer feedback when it comes to one’s achievements often comes hand in hand with feedback about goals.

One of the best goal-setting techniques is to attach new goals to employee praise . That is why our next 10 peer review phrase examples are all about goals and achievements.

While these peer feedback examples may not directly align with your situation, customizing them according to context is simple enough!

- “Your goal to increase client engagement has been impactful. Reviewing and aligning these goals quarterly could further enhance our outreach efforts.”

- “Setting a goal to reduce project delivery times has been a great initiative. Breaking this down into smaller milestones could provide clearer pathways to success.”

- “Your aim to improve team collaboration is commendable. Identifying specific collaboration tools and practices could make this goal even more attainable.”

- “I’ve noticed your dedication to personal development. Establishing specific learning goals for each quarter could provide a structured path for your growth.”

- “Celebrating your achievement in enhancing our customer satisfaction ratings is important. Let’s set new targets to maintain this positive trajectory.”

- “Your goal to enhance our brand’s social media presence has yielded great results. Next, we could focus on increasing engagement rates to build deeper connections with our audience.”

- “While striving to increase sales is crucial, ensuring we have measurable and realistic targets will help maintain team morale and focus.”

- “Your efforts to improve internal communication are showing results. Setting specific objectives for team meetings and feedback sessions could further this progress.”

- “Achieving certification in your field was a significant milestone. Now, setting a goal to apply this new knowledge in our projects could maximize its impact.”

- “Your initiative to lead community engagement projects has been inspiring. Let’s set benchmarks to track the positive changes and plan our next steps in community involvement.”

Peer Evaluation Examples: Communication Skills

The last area of peer feedback we will be covering in this post today is peer review examples on communication skills.

Since the simple act of delivering peer review or peer feedback depends heavily on one’s communication skills, it goes without saying that this is a crucial area.

Below you will find 10 sample peer evaluation examples that you can apply to your workplace with ease.

Go over each peer review phrase and select the ones that best reflect the feedback you want to offer to your peers!

- “Your ability to articulate complex ideas in simple terms has been a great asset. Continuously refining this skill can enhance our team’s understanding and collaboration.”

- “The strategies you’ve implemented to improve team collaboration have been effective. Encouraging others to share their methods can foster a more collaborative environment.”

- “Navigating the recent conflict with diplomacy and tact was impressive. Your approach could serve as a model for effective conflict resolution within the team.”

- “Your active listening during meetings is commendable. It not only shows respect for colleagues but also ensures that all viewpoints are considered, enhancing our decision-making process.”

- “Your adaptability in adjusting communication styles to different team members is key to our project’s success. This skill is crucial for maintaining effective collaboration across diverse teams.”

- “The leadership you displayed in coordinating the team project was instrumental in its success. Your ability to align everyone’s efforts towards a common goal is a valuable skill.”

- “Your presentation skills have significantly improved, effectively engaging and informing the team. Continued focus on this area can make your communication even more impactful.”

- “Promoting inclusivity in your communication has positively influenced our team’s dynamics. This approach ensures that everyone feels valued and heard.”

- “Your negotiation skills during the last project were key to reaching a consensus. Developing these skills further can enhance your effectiveness in future discussions.”

- “The feedback culture you’re fostering is creating a more dynamic and responsive team environment. Encouraging continuous feedback can lead to ongoing improvements and innovation.”

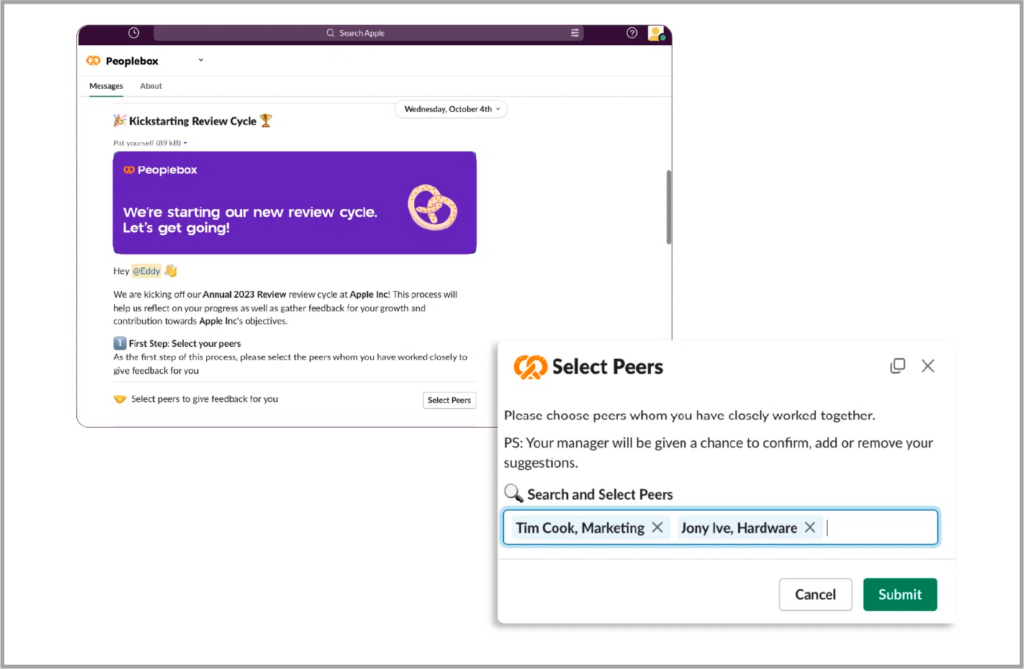

Best Way To Offer Peer Feedback: Using Feedback Software!

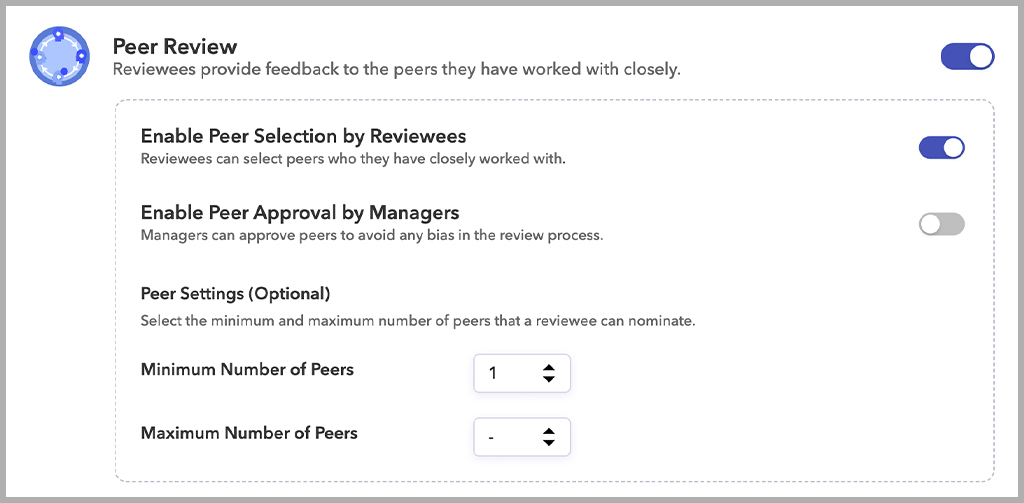

If you are offering feedback to peers or conducting peer review, you need a performance management tool that lets you digitize, streamline, and structure those processes effectively.

To help you do just that let us show you just how you can use the best performance management software for Microsoft Teams , Teamflect, to deliver feedback to peers!

While this particular example approaches peer review in the form of direct feedback, Teamflect can also help implement peer reviews inside performance appraisals for a complete peer evaluation.

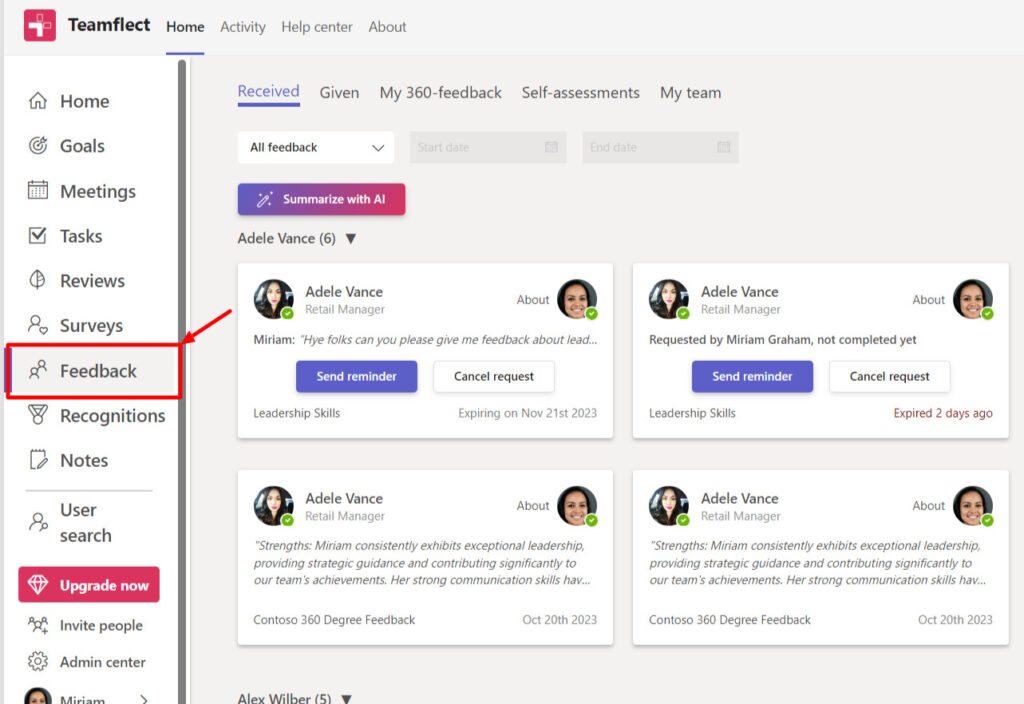

Step 1: Head over to Teamflect’s Feedback Module

While Teamflect users can exchange feedback without leaving Microsoft Teams chat with the help of customizable feedback templates, the feedback module itself serves as a hub for all the feedback given and received.

Once inside the feedback module, all you have to do is click the “New Feedback” button to start giving structured and effective feedback to your peers!

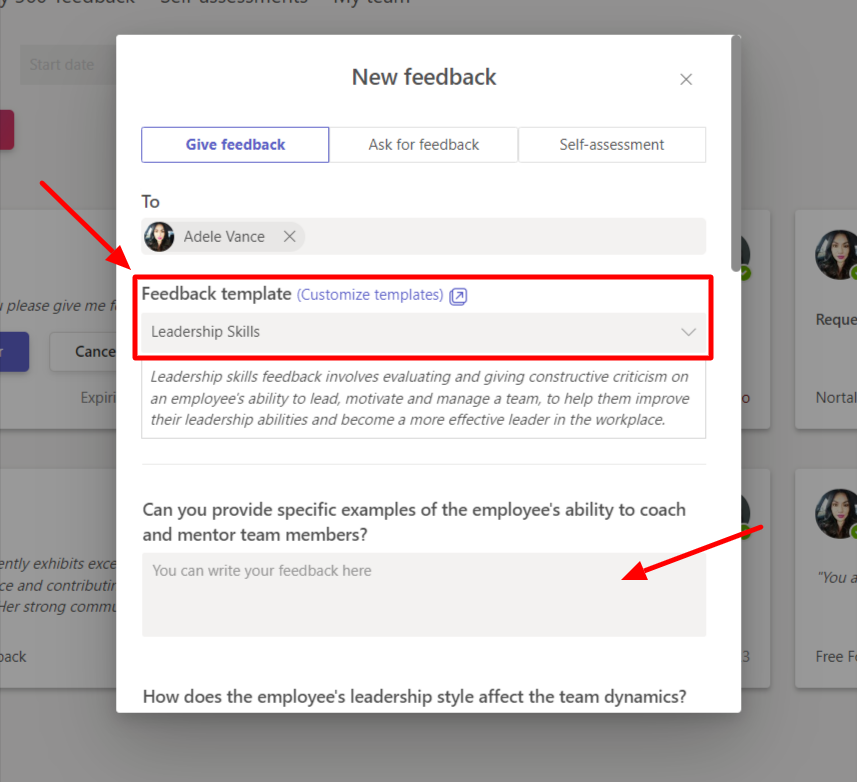

Step 2: Select a feedback template

Teamflect has an extensive library of customizable feedback templates. You can either directly pick a template that best fits the topic on which you would like to deliver feedback to your peer or create a custom feedback template specifically for peer evaluations.

Once you’ve chosen your template, you can start giving feedback right then and there!

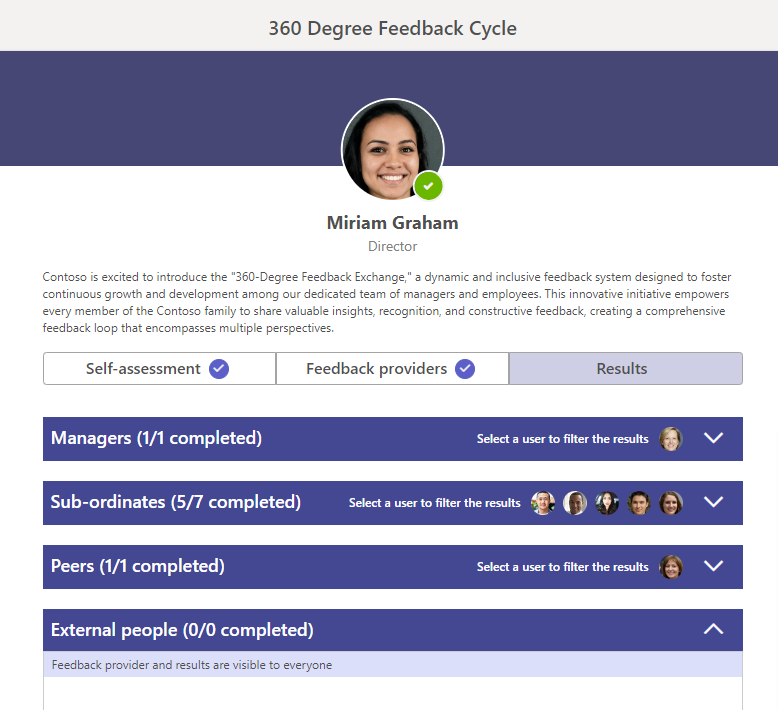

Optional: 360-Degree Feedback

Why stop with peer review? Include all stakeholders around the performance cycle into the feedback process with one of the most intuitive 360-degree feedback systems out there.

Request feedback about yourself or about someone else from everyone involved in their performance, including managers, direct reports, peers, and external parties.

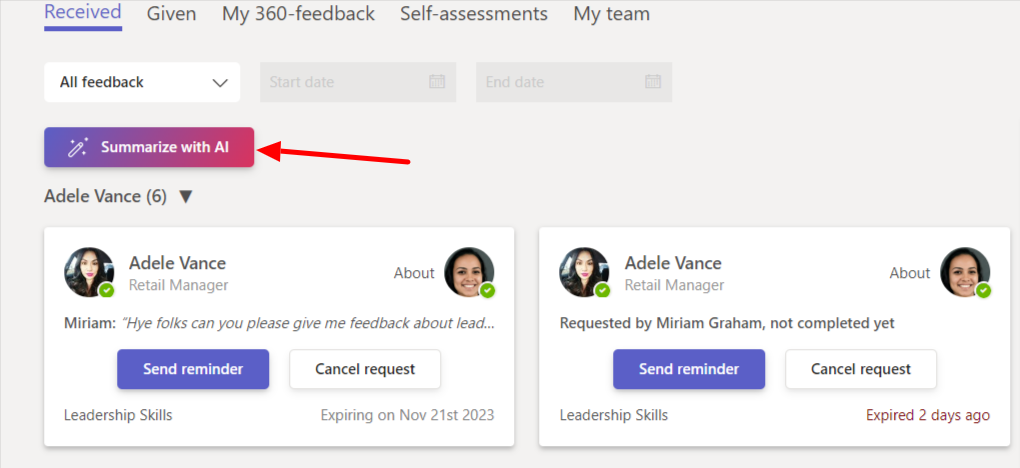

Optional: Summarize feedback with AI

If you have more feedback on your hands then you can go through, summarize that feedback with the help of Teamflect’s AI assistant!

What Are The Benefits of Implementing Peer Review Systems?

Peer reviews have plenty of benefits to the individuals delivering the peer review, the ones receiving the peer evaluation, as well as the organization itself. So here are the 5 benefits of implementing peer feedback programs organization-wide.

1. Enhanced Learning and Understanding Peer feedback promotes a deeper engagement with the material or project at hand. When individuals know they will be receiving and providing feedback, they have a brand new incentive to engage more thoroughly with the content.

2. Cultivation of Open Communication and Continuous Improvement Establishing a norm where feedback is regularly exchanged fosters an environment of open communication. People become more accustomed to giving and receiving constructive criticism, reducing defensiveness, and fostering a culture where continuous improvement is the norm.

3. Multiple Perspectives Enhance Quality Peer feedback introduces multiple viewpoints, which can significantly enhance the quality of work. Different perspectives can uncover blind spots, introduce new ideas, and challenge existing ones, leading to more refined and well-rounded outcomes.

4. Encouragement of Personal and Professional Development Feedback from peers can play a crucial role in personal and professional growth. It can highlight areas of strength and identify opportunities for development, guiding individuals toward their full potential.

Related Posts:

Written by emre ok.

Emre is a content writer at Teamflect who aims to share fun and unique insight into the world of performance management.

15 Performance Review Competencies to Track in 2024

10 Best Employee Promotion Interview Questions & Answers!

Peer Review Examples (300 Key Positive, Negative Phrases)

By Status.net Editorial Team on February 4, 2024 — 18 minutes to read

Peer review is a process that helps you evaluate your work and that of others. It can be a valuable tool in ensuring the quality and credibility of any project or piece of research. Engaging in peer review lets you take a fresh look at something you may have become familiar with. You’ll provide constructive criticism to your peers and receive the same in return, allowing everyone to learn and grow.

Finding the right words to provide meaningful feedback can be challenging. This article provides positive and negative phrases to help you conduct more effective peer reviews.

Crafting Positive Feedback

Praising professionalism.

- Your punctuality is exceptional.

- You always manage to stay focused under pressure.

- I appreciate your respect for deadlines.

- Your attention to detail is outstanding.

- You exhibit great organizational skills.

- Your dedication to the task at hand is commendable.

- I love your professionalism in handling all situations.

- Your ability to maintain a positive attitude is inspiring.

- Your commitment to the project shows in the results.

- I value your ability to think critically and come up with solutions.

Acknowledging Skills

- Your technical expertise has greatly contributed to our team’s success.

- Your creative problem-solving skills are impressive.

- You have an exceptional way of explaining complex ideas.

- I admire your ability to adapt to change quickly.

- Your presentation skills are top-notch.

- You have a unique flair for motivating others.

- Your negotiation skills have led to wonderful outcomes.

- Your skillful project management ensured smooth progress.

- Your research skills have produced invaluable findings.

- Your knack for diplomacy has fostered great relationships.

Encouraging Teamwork

- Your ability to collaborate effectively is evident.

- You consistently go above and beyond to help your teammates.

- I appreciate your eagerness to support others.

- You always bring out the best in your team members.

- You have a gift for uniting people in pursuit of a goal.

- Your clear communication makes collaboration a breeze.

- You excel in creating a nurturing atmosphere for the team.

- Your leadership qualities are incredibly valuable to our team.

- I admire your respectful attitude towards team members.

- You have a knack for creating a supportive and inclusive environment.

Highlighting Achievements

- Your sales performance this quarter has been phenomenal.

- Your cost-saving initiatives have positively impacted the budget.

- Your customer satisfaction ratings have reached new heights.

- Your successful marketing campaign has driven impressive results.

- You’ve shown a strong improvement in meeting your performance goals.

- Your efforts have led to a significant increase in our online presence.

- The success of the event can be traced back to your careful planning.

- Your project was executed with precision and efficiency.

- Your innovative product ideas have provided a competitive edge.

- You’ve made great strides in strengthening our company culture.

Formulating Constructive Criticism

Addressing areas for improvement.

When providing constructive criticism, try to be specific in your comments and avoid generalizing. Here are 30 example phrases:

- You might consider revising this sentence for clarity.

- This section could benefit from more detailed explanations.

- It appears there may be a discrepancy in your data.

- This paragraph might need more support from the literature.

- I suggest reorganizing this section to improve coherence.

- The introduction can be strengthened by adding context.

- There may be some inconsistencies that need to be resolved.

- This hypothesis needs clearer justification.

- The methodology could benefit from additional details.

- The conclusion may need a stronger synthesis of the findings.

- You might want to consider adding examples to illustrate your point.

- Some of the terminology used here could be clarified.

- It would be helpful to see more information on your sources.

- A summary might help tie this section together.

- You may want to consider rephrasing this question.

- An elaboration on your methods might help the reader understand your approach.

- This image could be clearer if it were larger or had labels.

- Try breaking down this complex idea into smaller parts.

- You may want to revisit your tone to ensure consistency.

- The transitions between topics could be smoother.

- Consider adding citations to support your argument.

- The tables and figures could benefit from clearer explanations.

- It might be helpful to revisit your formatting for better readability.

- This discussion would benefit from additional perspectives.

- You may want to address any logical gaps in your argument.

- The literature review might benefit from a more critical analysis.

- You might want to expand on this point to strengthen your case.

- The presentation of your results could be more organized.

- It would be helpful if you elaborated on this connection in your analysis.

- A more in-depth conclusion may better tie your ideas together.

Offering Specific Recommendations

- You could revise this sentence to say…

- To make this section more detailed, consider discussing…

- To address the data discrepancy, double-check the data at this point.

- You could add citations from these articles to strengthen your point.

- To improve coherence, you could move this paragraph to…

- To add context, consider mentioning…

- To resolve these inconsistencies, check…

- To justify your hypothesis, provide evidence from…

- To add detail to your methodology, describe…

- To synthesize your findings in the conclusion, mention…

- To illustrate your point, consider giving an example of…

- To clarify terminology, you could define…

- To provide more information on sources, list…

- To create a summary, touch upon these key points.

- To rephrase this question, try asking…

- To expand upon your methods, discuss…

- To make this image clearer, increase its size or add labels for…

- To break down this complex idea, consider explaining each part like…

- To maintain a consistent tone, avoid using…

- To smooth transitions between topics, use phrases such as…

- To support your argument, cite sources like…

- To explain tables and figures, add captions with…

- To improve readability, use formatting elements like headings, bullet points, etc.

- To include additional perspectives in your discussion, mention…

- To address logical gaps, provide reasoning for…

- To create a more critical analysis in your literature review, critique…

- To expand on this point, add details about…

- To present your results more organized, use subheadings, tables, or graphs.

- To elaborate on connections in your analysis, show how x relates to y by…

- To provide a more in-depth conclusion, tie together the major findings by…

Highlighting Positive Aspects

When offering constructive criticism, maintaining a friendly and positive tone is important. Encourage improvement by highlighting the positive aspects of the work. For example:

- Great job on this section!

- Your writing is clear and easy to follow.

- I appreciate your attention to detail.

- Your conclusions are well supported by your research.

- Your argument is compelling and engaging.

- I found your analysis to be insightful.

- The organization of your paper is well thought out.

- Your use of citations effectively strengthens your claims.

- Your methodology is well explained and thorough.

- I’m impressed with the depth of your literature review.

- Your examples are relevant and informative.

- You’ve made excellent connections throughout your analysis.

- Your grasp of the subject matter is impressive.

- The clarity of your images and figures is commendable.

- Your transitions between topics are smooth and well-executed.

- You’ve effectively communicated complex ideas.

- Your writing style is engaging and appropriate for your target audience.

- Your presentation of results is easy to understand.

- Your tone is consistent and professional.

- Your overall argument is persuasive.

- Your use of formatting helps guide the reader.

- Your tables, graphs, and illustrations enhance your argument.

- Your interpretation of the data is insightful and well-reasoned.

- Your discussion is balanced and well-rounded.

- The connections you make throughout your paper are thought-provoking.

- Your approach to the topic is fresh and innovative.

- You’ve done a fantastic job synthesizing information from various sources.

- Your attention to the needs of the reader is commendable.

- The care you’ve taken in addressing counterarguments is impressive.

- Your conclusions are well-drawn and thought-provoking.

Balancing Feedback

Combining positive and negative remarks.

When providing peer review feedback, it’s important to balance positive and negative comments: this approach allows the reviewer to maintain a friendly tone and helps the recipient feel reassured.

Examples of Positive Remarks:

- Well-organized

- Clear and concise

- Excellent use of examples

- Thorough research

- Articulate argument

- Engaging writing style

- Thoughtful analysis

- Strong grasp of the topic

- Relevant citations

- Logical structure

- Smooth transitions

- Compelling conclusion

- Original ideas

- Solid supporting evidence

- Succinct summary

Examples of Negative Remarks:

- Unclear thesis

- Lacks focus

- Insufficient evidence

- Overgeneralization

- Inconsistent argument

- Redundant phrasing

- Jargon-filled language

- Poor formatting

- Grammatical errors

- Unconvincing argument

- Confusing organization

- Needs more examples

- Weak citations

- Unsupported claims

- Ambiguous phrasing

Ensuring Objectivity

Avoid using emotionally charged language or personal opinions. Instead, base your feedback on facts and evidence.

For example, instead of saying, “I don’t like your choice of examples,” you could say, “Including more diverse examples would strengthen your argument.”

Personalizing Feedback

Tailor your feedback to the individual and their work, avoiding generic or blanket statements. Acknowledge the writer’s strengths and demonstrate an understanding of their perspective. Providing personalized, specific, and constructive comments will enable the recipient to grow and improve their work.

For instance, you might say, “Your writing style is engaging, but consider adding more examples to support your points,” or “I appreciate your thorough research, but be mindful of avoiding overgeneralizations.”

Phrases for Positive Feedback

- Great job on the presentation, your research was comprehensive.

- I appreciate your attention to detail in this project.

- You showed excellent teamwork and communication skills.

- Impressive progress on the task, keep it up!

- Your creativity really shined in this project.

- Thank you for your hard work and dedication.

- Your problem-solving skills were crucial to the success of this task.

- I am impressed by your ability to multitask.

- Your time management in finishing this project was stellar.

- Excellent initiative in solving the issue.

- Your work showcases your exceptional analytical skills.

- Your positive attitude is contagious!

- You were successful in making a complex subject easier to grasp.

- Your collaboration skills truly enhanced our team’s effectiveness.

- You handled the pressure and deadlines admirably.

- Your written communication is both thorough and concise.

- Your responsiveness to feedback is commendable.

- Your flexibility in adapting to new challenges is impressive.

- Thank you for your consistently accurate work.

- Your devotion to professional development is inspiring.

- You display strong leadership qualities.

- You demonstrate empathy and understanding in handling conflicts.

- Your active listening skills contribute greatly to our discussions.

- You consistently take ownership of your tasks.

- Your resourcefulness was key in overcoming obstacles.

- You consistently display a can-do attitude.

- Your presentation skills are top-notch!

- You are a valuable asset to our team.

- Your positive energy boosts team morale.

- Your work displays your tremendous growth in this area.

- Your ability to stay organized is commendable.

- You consistently meet or exceed expectations.

- Your commitment to self-improvement is truly inspiring.

- Your persistence in tackling challenges is admirable.

- Your ability to grasp new concepts quickly is impressive.

- Your critical thinking skills are a valuable contribution to our team.

- You demonstrate impressive technical expertise in your work.

- Your contributions make a noticeable difference.

- You effectively balance multiple priorities.

- You consistently take the initiative to improve our processes.

- Your ability to mentor and support others is commendable.

- You are perceptive and insightful in offering solutions to problems.

- You actively engage in discussions and share your opinions constructively.

- Your professionalism is a model for others.

- Your ability to quickly adapt to changes is commendable.

- Your work exemplifies your passion for excellence.

- Your desire to learn and grow is inspirational.

- Your excellent organizational skills are a valuable asset.

- You actively seek opportunities to contribute to the team’s success.

- Your willingness to help others is truly appreciated.

- Your presentation was both informative and engaging.

- You exhibit great patience and perseverance in your work.

- Your ability to navigate complex situations is impressive.

- Your strategic thinking has contributed to our success.

- Your accountability in your work is commendable.

- Your ability to motivate others is admirable.

- Your reliability has contributed significantly to the team’s success.

- Your enthusiasm for your work is contagious.

- Your diplomatic approach to resolving conflict is commendable.

- Your ability to persevere despite setbacks is truly inspiring.

- Your ability to build strong relationships with clients is impressive.

- Your ability to prioritize tasks is invaluable to our team.

- Your work consistently demonstrates your commitment to quality.

- Your ability to break down complex information is excellent.

- Your ability to think on your feet is greatly appreciated.

- You consistently go above and beyond your job responsibilities.

- Your attention to detail consistently ensures the accuracy of your work.

- Your commitment to our team’s success is truly inspiring.

- Your ability to maintain composure under stress is commendable.

- Your contributions have made our project a success.

- Your confidence and conviction in your work is motivating.

- Thank you for stepping up and taking the lead on this task.

- Your willingness to learn from mistakes is encouraging.

- Your decision-making skills contribute greatly to the success of our team.

- Your communication skills are essential for our team’s effectiveness.

- Your ability to juggle multiple tasks simultaneously is impressive.

- Your passion for your work is infectious.

- Your courage in addressing challenges head-on is remarkable.

- Your ability to prioritize tasks and manage your own workload is commendable.

- You consistently demonstrate strong problem-solving skills.

- Your work reflects your dedication to continuous improvement.

- Your sense of humor helps lighten the mood during stressful times.

- Your ability to take constructive feedback on board is impressive.

- You always find opportunities to learn and develop your skills.

- Your attention to safety protocols is much appreciated.

- Your respect for deadlines is commendable.

- Your focused approach to work is motivating to others.

- You always search for ways to optimize our processes.

- Your commitment to maintaining a high standard of work is inspirational.

- Your excellent customer service skills are a true asset.

- You demonstrate strong initiative in finding solutions to problems.

- Your adaptability to new situations is an inspiration.

- Your ability to manage change effectively is commendable.

- Your proactive communication is appreciated by the entire team.

- Your drive for continuous improvement is infectious.

- Your input consistently elevates the quality of our discussions.

- Your ability to handle both big picture and detailed tasks is impressive.

- Your integrity and honesty are commendable.

- Your ability to take on new responsibilities is truly inspiring.

- Your strong work ethic is setting a high standard for the entire team.

Phrases for Areas of Improvement

- You might consider revisiting the structure of your argument.

- You could work on clarifying your main point.

- Your presentation would benefit from additional examples.

- Perhaps try exploring alternative perspectives.

- It would be helpful to provide more context for your readers.

- You may want to focus on improving the flow of your writing.

- Consider incorporating additional evidence to support your claims.

- You could benefit from refining your writing style.

- It would be useful to address potential counterarguments.

- You might want to elaborate on your conclusion.

- Perhaps consider revisiting your methodology.

- Consider providing a more in-depth analysis.

- You may want to strengthen your introduction.

- Your paper could benefit from additional proofreading.

- You could work on making your topic more accessible to your readers.

- Consider tightening your focus on key points.

- It might be helpful to add more visual aids to your presentation.

- You could strive for more cohesion between your sections.

- Your abstract would benefit from a more concise summary.

- Perhaps try to engage your audience more actively.

- You may want to improve the organization of your thoughts.

- It would be useful to cite more reputable sources.

- Consider emphasizing the relevance of your topic.

- Your argument could benefit from stronger parallels.

- You may want to add transitional phrases for improved readability.

- It might be helpful to provide more concrete examples.

- You could work on maintaining a consistent tone throughout.

- Consider employing a more dynamic vocabulary.

- Your project would benefit from a clearer roadmap.

- Perhaps explore the limitations of your study.

- It would be helpful to demonstrate the impact of your research.

- You could work on the consistency of your formatting.

- Consider refining your choice of images.

- You may want to improve the pacing of your presentation.

- Make an effort to maintain eye contact with your audience.

- Perhaps adding humor or anecdotes would engage your listeners.

- You could work on modulating your voice for emphasis.

- It would be helpful to practice your timing.

- Consider incorporating more interactive elements.

- You might want to speak more slowly and clearly.

- Your project could benefit from additional feedback from experts.

- You might want to consider the practical implications of your findings.

- It would be useful to provide a more user-friendly interface.

- Consider incorporating a more diverse range of sources.

- You may want to hone your presentation to a specific audience.

- You could work on the visual design of your slides.

- Your writing might benefit from improved grammatical accuracy.

- It would be helpful to reduce jargon for clarity.

- You might consider refining your data visualization.

- Perhaps provide a summary of key points for easier comprehension.

- You may want to develop your skills in a particular area.

- Consider attending workshops or trainings for continued learning.

- Your project could benefit from stronger collaboration.

- It might be helpful to seek guidance from mentors or experts.

- You could work on managing your time more effectively.

- It would be useful to set goals and priorities for improvement.

- You might want to identify areas where you can grow professionally.

- Consider setting aside time for reflection and self-assessment.

- Perhaps develop strategies for overcoming challenges.

- You could work on increasing your confidence in public speaking.

- Consider collaborating with others for fresh insights.

- You may want to practice active listening during discussions.

- Be open to feedback and constructive criticism.

- It might be helpful to develop empathy for team members’ perspectives.

- You could work on being more adaptable to change.

- It would be useful to improve your problem-solving abilities.

- Perhaps explore opportunities for networking and engagement.

- You may want to set personal benchmarks for success.

- You might benefit from being more proactive in seeking opportunities.

- Consider refining your negotiation and persuasion skills.

- It would be helpful to enhance your interpersonal communication.

- You could work on being more organized and detail-oriented.

- You may want to focus on strengthening leadership qualities.

- Consider improving your ability to work effectively under pressure.

- Encourage open dialogue among colleagues to promote a positive work environment.

- It might be useful to develop a growth mindset.

- Be open to trying new approaches and techniques.

- Consider building stronger relationships with colleagues and peers.

- It would be helpful to manage expectations more effectively.

- You might want to delegate tasks more efficiently.

- You could work on your ability to prioritize workload effectively.

- It would be useful to review and update processes and procedures regularly.

- Consider creating a more inclusive working environment.

- You might want to seek opportunities to mentor and support others.

- Recognize and celebrate the accomplishments of your team members.

- Consider developing a more strategic approach to decision-making.

- You may want to establish clear goals and objectives for your team.

- It would be helpful to provide regular and timely feedback.

- Consider enhancing your delegation and time-management skills.

- Be open to learning from your team’s diverse skill sets.

- You could work on cultivating a collaborative culture.

- It would be useful to engage in continuous professional development.

- Consider seeking regular feedback from colleagues and peers.

- You may want to nurture your own personal resilience.

- Reflect on areas of improvement and develop an action plan.

- It might be helpful to share your progress with a mentor or accountability partner.

- Encourage your team to support one another’s growth and development.

- Consider celebrating and acknowledging small successes.

- You could work on cultivating effective communication habits.

- Be willing to take calculated risks and learn from any setbacks.

Frequently Asked Questions

How can i phrase constructive feedback in peer evaluations.

To give constructive feedback in peer evaluations, try focusing on specific actions or behaviors that can be improved. Use phrases like “I noticed that…” or “You might consider…” to gently introduce your observations. For example, “You might consider asking for help when handling multiple tasks to improve time management.”

What are some examples of positive comments in peer reviews?

- “Your presentation was engaging and well-organized, making it easy for the team to understand.”

- “You are a great team player, always willing to help others and contribute to the project’s success.”

- “Your attention to detail in documentation has made it easier for the whole team to access information quickly.”

Can you suggest ways to highlight strengths in peer appraisals?

Highlighting strengths in peer appraisals can be done by mentioning specific examples of how the individual excelled or went above and beyond expectations. You can also point out how their strengths positively impacted the team. For instance:

- “Your effective communication skills ensured that everyone was on the same page during the project.”

- “Your creativity in problem-solving helped resolve a complex issue that benefited the entire team.”

What are helpful phrases to use when noting areas for improvement in a peer review?

When noting areas for improvement in a peer review, try using phrases that encourage growth and development. Some examples include:

- “To enhance your time management skills, you might try prioritizing tasks or setting deadlines.”

- “By seeking feedback more often, you can continue to grow and improve in your role.”

- “Consider collaborating more with team members to benefit from their perspectives and expertise.”

How should I approach writing a peer review for a manager differently?

When writing a peer review for a manager, it’s important to focus on their leadership qualities and how they can better support their team. Some suggestions might include:

- “Encouraging more open communication can help create a more collaborative team environment.”

- “By providing clearer expectations or deadlines, you can help reduce confusion and promote productivity.”

- “Consider offering recognition to team members for their hard work, as this can boost motivation and morale.”

What is a diplomatic way to discuss negative aspects in a peer review?

Discussing negative aspects in a peer review requires tact and empathy. Try focusing on behaviors and actions rather than personal attributes, and use phrases that suggest areas for growth. For example:

- “While your dedication to the project is admirable, it might be beneficial to delegate some tasks to avoid burnout.”

- “Improving communication with colleagues can lead to better alignment within the team.”

- “By asking for feedback, you can identify potential blind spots and continue to grow professionally.”

- Flexibility: 25 Performance Review Phrases Examples

- Job Knowledge Performance Review Phrases (Examples)

- Integrity: 25 Performance Review Phrases Examples

- 60 Smart Examples: Positive Feedback for Manager in a Review

- 30 Employee Feedback Examples (Positive & Negative)

- Initiative: 25 Performance Review Phrases Examples

The Savvy Scientist

Experiences of a London PhD student and beyond

My Complete Guide to Academic Peer Review: Example Comments & How to Make Paper Revisions

Once you’ve submitted your paper to an academic journal you’re in the nerve-racking position of waiting to hear back about the fate of your work. In this post we’ll cover everything from potential responses you could receive from the editor and example peer review comments through to how to submit revisions.

My first first-author paper was reviewed by five (yes 5!) reviewers and since then I’ve published several others papers, so now I want to share the insights I’ve gained which will hopefully help you out!

This post is part of my series to help with writing and publishing your first academic journal paper. You can find the whole series here: Writing an academic journal paper .

The Peer Review Process

When you submit a paper to a journal, the first thing that will happen is one of the editorial team will do an initial assessment of whether or not the article is of interest. They may decide for a number of reasons that the article isn’t suitable for the journal and may reject the submission before even sending it out to reviewers.

If this happens hopefully they’ll have let you know quickly so that you can move on and make a start targeting a different journal instead.

Handy way to check the status – Sign in to the journal’s submission website and have a look at the status of your journal article online. If you can see that the article is under review then you’ve passed that first hurdle!

When your paper is under peer review, the journal will have set out a framework to help the reviewers assess your work. Generally they’ll be deciding whether the work is to a high enough standard.

Interested in reading about what reviewers are looking for? Check out my post on being a reviewer for the first time. Peer-Reviewing Journal Articles: Should You Do It? Sharing What I Learned From My First Experiences .

Once the reviewers have made their assessments, they’ll return their comments and suggestions to the editor who will then decide how the article should proceed.

How Many People Review Each Paper?

The editor ideally wants a clear decision from the reviewers as to whether the paper should be accepted or rejected. If there is no consensus among the reviewers then the editor may send your paper out to more reviewers to better judge whether or not to accept the paper.

If you’ve got a lot of reviewers on your paper it isn’t necessarily that the reviewers disagreed about accepting your paper.

You can also end up with lots of reviewers in the following circumstance:

- The editor asks a certain academic to review the paper but doesn’t get a response from them

- The editor asks another academic to step in

- The initial reviewer then responds

Next thing you know your work is being scrutinised by extra pairs of eyes!

As mentioned in the intro, my first paper ended up with five reviewers!

Potential Journal Responses

Assuming that the paper passes the editor’s initial evaluation and is sent out for peer-review, here are the potential decisions you may receive:

- Reject the paper. Sadly the editor and reviewers decided against publishing your work. Hopefully they’ll have included feedback which you can incorporate into your submission to another journal. I’ve had some rejections and the reviewer comments were genuinely useful.

- Accept the paper with major revisions . Good news: with some more work your paper could get published. If you make all the changes that the reviewers suggest, and they’re happy with your responses, then it should get accepted. Some people see major revisions as a disappointment but it doesn’t have to be.

- Accept the paper with minor revisions. This is like getting a major revisions response but better! Generally minor revisions can be addressed quickly and often come down to clarifying things for the reviewers: rewording, addressing minor concerns etc and don’t require any more experiments or analysis. You stand a really good chance of getting the paper published if you’ve been given a minor revisions result.

- Accept the paper with no revisions . I’m not sure that this ever really happens, but it is potentially possible if the reviewers are already completely happy with your paper!

Keen to know more about academic publishing? My series on publishing is now available as a free eBook. It includes my experiences being a peer reviewer. Click the image below for access.

Example Peer Review Comments & Addressing Reviewer Feedback

If your paper has been accepted but requires revisions, the editor will forward to you the comments and concerns that the reviewers raised. You’ll have to address these points so that the reviewers are satisfied your work is of a publishable standard.

It is extremely important to take this stage seriously. If you don’t do a thorough job then the reviewers won’t recommend that your paper is accepted for publication!

You’ll have to put together a resubmission with your co-authors and there are two crucial things you must do:

- Make revisions to your manuscript based off reviewer comments

- Reply to the reviewers, telling them the changes you’ve made and potentially changes you’ve not made in instances where you disagree with them. Read on to see some example peer review comments and how I replied!

Before making any changes to your actual paper, I suggest having a thorough read through the reviewer comments.

Once you’ve read through the comments you might be keen to dive straight in and make the changes in your paper. Instead, I actually suggest firstly drafting your reply to the reviewers.

Why start with the reply to reviewers? Well in a way it is actually potentially more important than the changes you’re making in the manuscript.

Imagine when a reviewer receives your response to their comments: you want them to be able to read your reply document and be satisfied that their queries have largely been addressed without even having to open the updated draft of your manuscript. If you do a good job with the replies, the reviewers will be better placed to recommend the paper be accepted!

By starting with your reply to the reviewers you’ll also clarify for yourself what changes actually have to be made to the paper.

So let’s now cover how to reply to the reviewers.

1. Replying to Journal Reviewers

It is so important to make sure you do a solid job addressing your reviewers’ feedback in your reply document. If you leave anything unanswered you’re asking for trouble, which in this case means either a rejection or another round of revisions: though some journals only give you one shot! Therefore make sure you’re thorough, not just with making the changes but demonstrating the changes in your replies.

It’s no good putting in the work to revise your paper but not evidence it in your reply to the reviewers!

There may be points that reviewers raise which don’t appear to necessitate making changes to your manuscript, but this is rarely the case. Even for comments or concerns they raise which are already addressed in the paper, clearly those areas could be clarified or highlighted to ensure that future readers don’t get confused.

How to Reply to Journal Reviewers

Some journals will request a certain format for how you should structure a reply to the reviewers. If so this should be included in the email you receive from the journal’s editor. If there are no certain requirements here is what I do:

- Copy and paste all replies into a document.

- Separate out each point they raise onto a separate line. Often they’ll already be nicely numbered but sometimes they actually still raise separate issues in one block of text. I suggest separating it all out so that each query is addressed separately.

- Form your reply for each point that they raise. I start by just jotting down notes for roughly how I’ll respond. Once I’m happy with the key message I’ll write it up into a scripted reply.

- Finally, go through and format it nicely and include line number references for the changes you’ve made in the manuscript.

By the end you’ll have a document that looks something like:

Reviewer 1 Point 1: [Quote the reviewer’s comment] Response 1: [Address point 1 and say what revisions you’ve made to the paper] Point 2: [Quote the reviewer’s comment] Response 2: [Address point 2 and say what revisions you’ve made to the paper] Then repeat this for all comments by all reviewers!

What To Actually Include In Your Reply To Reviewers

For every single point raised by the reviewers, you should do the following:

- Address their concern: Do you agree or disagree with the reviewer’s comment? Either way, make your position clear and justify any differences of opinion. If the reviewer wants more clarity on an issue, provide it. It is really important that you actually address their concerns in your reply. Don’t just say “Thanks, we’ve changed the text”. Actually include everything they want to know in your reply. Yes this means you’ll be repeating things between your reply and the revisions to the paper but that’s fine.

- Reference changes to your manuscript in your reply. Once you’ve answered the reviewer’s question, you must show that you’re actually using this feedback to revise the manuscript. The best way to do this is to refer to where the changes have been made throughout the text. I personally do this by include line references. Make sure you save this right until the end once you’ve finished making changes!

Example Peer Review Comments & Author Replies

In order to understand how this works in practice I’d suggest reading through a few real-life example peer review comments and replies.

The good news is that published papers often now include peer-review records, including the reviewer comments and authors’ replies. So here are two feedback examples from my own papers:

Example Peer Review: Paper 1

Quantifying 3D Strain in Scaffold Implants for Regenerative Medicine, J. Clark et al. 2020 – Available here

This paper was reviewed by two academics and was given major revisions. The journal gave us only 10 days to get them done, which was a bit stressful!

- Reviewer Comments

- My reply to Reviewer 1

- My reply to Reviewer 2

One round of reviews wasn’t enough for Reviewer 2…

- My reply to Reviewer 2 – ROUND 2

Thankfully it was accepted after the second round of review, and actually ended up being selected for this accolade, whatever most notable means?!

Nice to see our recent paper highlighted as one of the most notable articles, great start to the week! Thanks @Materials_mdpi 😀 #openaccess & available here: https://t.co/AKWLcyUtpC @ICBiomechanics @julianrjones @saman_tavana pic.twitter.com/ciOX2vftVL — Jeff Clark (@savvy_scientist) December 7, 2020

Example Peer Review: Paper 2

Exploratory Full-Field Mechanical Analysis across the Osteochondral Tissue—Biomaterial Interface in an Ovine Model, J. Clark et al. 2020 – Available here

This paper was reviewed by three academics and was given minor revisions.

- My reply to Reviewer 3

I’m pleased to say it was accepted after the first round of revisions 🙂

Things To Be Aware Of When Replying To Peer Review Comments

- Generally, try to make a revision to your paper for every comment. No matter what the reviewer’s comment is, you can probably make a change to the paper which will improve your manuscript. For example, if the reviewer seems confused about something, improve the clarity in your paper. If you disagree with the reviewer, include better justification for your choices in the paper. It is far more favourable to take on board the reviewer’s feedback and act on it with actual changes to your draft.

- Organise your responses. Sometimes journals will request the reply to each reviewer is sent in a separate document. Unless they ask for it this way I stick them all together in one document with subheadings eg “Reviewer 1” etc.

- Make sure you address each and every question. If you dodge anything then the reviewer will have a valid reason to reject your resubmission. You don’t need to agree with them on every point but you do need to justify your position.

- Be courteous. No need to go overboard with compliments but stay polite as reviewers are providing constructive feedback. I like to add in “We thank the reviewer for their suggestion” every so often where it genuinely warrants it. Remember that written language doesn’t always carry tone very well, so rather than risk coming off as abrasive if I don’t agree with the reviewer’s suggestion I’d rather be generous with friendliness throughout the reply.

2. How to Make Revisions To Your Paper

Once you’ve drafted your replies to the reviewers, you’ve actually done a lot of the ground work for making changes to the paper. Remember, you are making changes to the paper based off the reviewer comments so you should regularly be referring back to the comments to ensure you’re not getting sidetracked.

Reviewers could request modifications to any part of your paper. You may need to collect more data, do more analysis, reformat some figures, add in more references or discussion or any number of other revisions! So I can’t really help with everything, even so here is some general advice:

- Use tracked-changes. This is so important. The editor and reviewers need to be able to see every single change you’ve made compared to your first submission. Sometimes the journal will want a clean copy too but always start with tracked-changes enabled then just save a clean copy afterwards.

- Be thorough . Try to not leave any opportunity for the reviewers to not recommend your paper to be published. Any chance you have to satisfy their concerns, take it. For example if the reviewers are concerned about sample size and you have the means to include other experiments, consider doing so. If they want to see more justification or references, be thorough. To be clear again, this doesn’t necessarily mean making changes you don’t believe in. If you don’t want to make a change, you can justify your position to the reviewers. Either way, be thorough.

- Use your reply to the reviewers as a guide. In your draft reply to the reviewers you should have already included a lot of details which can be incorporated into the text. If they raised a concern, you should be able to go and find references which address the concern. This reference should appear both in your reply and in the manuscript. As mentioned above I always suggest starting with the reply, then simply adding these details to your manuscript once you know what needs doing.

Putting Together Your Paper Revision Submission

- Once you’ve drafted your reply to the reviewers and revised manuscript, make sure to give sufficient time for your co-authors to give feedback. Also give yourself time afterwards to make changes based off of their feedback. I ideally give a week for the feedback and another few days to make the changes.

- When you’re satisfied that you’ve addressed the reviewer comments, you can think about submitting it. The journal may ask for another letter to the editor, if not I simply add to the top of the reply to reviewers something like:

“Dear [Editor], We are grateful to the reviewer for their positive and constructive comments that have led to an improved manuscript. Here, we address their concerns/suggestions and have tracked changes throughout the revised manuscript.”

Once you’re ready to submit:

- Double check that you’ve done everything that the editor requested in their email

- Double check that the file names and formats are as required

- Triple check you’ve addressed the reviewer comments adequately

- Click submit and bask in relief!

You won’t always get the paper accepted, but if you’re thorough and present your revisions clearly then you’ll put yourself in a really good position. Remember to try as hard as possible to satisfy the reviewers’ concerns to minimise any opportunity for them to not accept your revisions!

Best of luck!

I really hope that this post has been useful to you and that the example peer review section has given you some ideas for how to respond. I know how daunting it can be to reply to reviewers, and it is really important to try to do a good job and give yourself the best chances of success. If you’d like to read other posts in my academic publishing series you can find them here:

Blog post series: Writing an academic journal paper

Subscribe below to stay up to date with new posts in the academic publishing series and other PhD content.

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

Related Posts