Home — Essay Samples — History — Civil Rights Movement — About The Underground Railroad

About The Underground Railroad

- Categories: Civil Rights Movement Slavery in The World

About this sample

Words: 639 |

Published: Mar 20, 2024

Words: 639 | Page: 1 | 4 min read

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below:

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Prof. Kifaru

Verified writer

- Expert in: History

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

5 pages / 2408 words

3 pages / 1293 words

4 pages / 1816 words

2 pages / 790 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Civil Rights Movement

Rosa Parks: The Courage to Stand for ChangeIn the annals of American history, few names resonate as powerfully as Rosa Parks. Her act of defiance on a Montgomery bus in 1955 sparked a chain reaction that forever altered the [...]

In his book "A Magnificent Catastrophe: The Tumultuous Election of 1876 and the Making of the President," author Edward J. Larson delves into the intricacies of one of the most controversial presidential elections in American [...]

In the history of the United States, two prominent figures, Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X, have played pivotal roles in the fight for civil rights and equality. While both leaders had different approaches and ideologies, [...]

Madame Haupt is a significant character in the novel "Les Misérables" by Victor Hugo. Her role in the story is complex, and her actions and decisions have a profound impact on the lives of other characters. This essay will [...]

Civil rights activist Rosa Parks (February 4, 1913 to October 24, 2005) refused to surrender her seat to a white passenger on a segregated Montgomery, Alabama bus, which spurred on the 381-day Montgomery Bus Boycott that helped [...]

Rosa Parks is famous for a lot of things. But, she is best known for her civil rights action. This happen in December 1,1955 Montgomery, Alabama bus system. She refused to give up her sit to a white passenger on the bus. She was [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

ENCYCLOPEDIC ENTRY

The underground railroad.

During the era of slavery, the Underground Railroad was a network of routes, places, and people that helped enslaved people in the American South escape to the North.

Social Studies, U.S. History

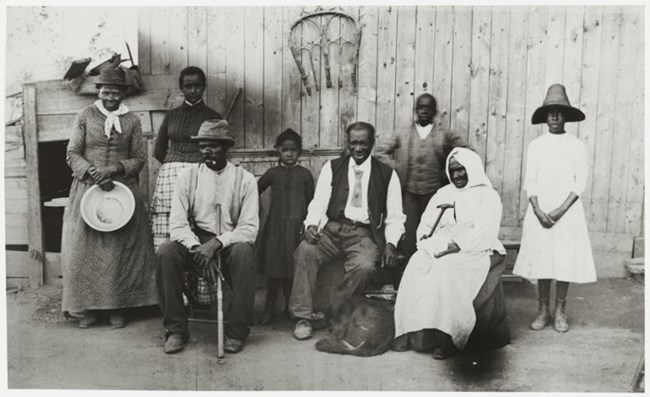

Home of Levi Coffin

Historic image of the home of American Quaker and abolitionist Levi Coffin located in Cincinnati, Ohio, with a group of African Americans out front.

Photography by Cincinnati Museum Center

During the era of slavery , the Underground Railroad was a network of routes, places, and people that helped enslaved people in the American South escape to the North. The name “ Underground Railroad ” was used metaphorically, not literally. It was not an actual railroad, but it served the same purpose—it transported people long distances. It also did not run underground, but through homes, barns, churches, and businesses. The people who worked for the Underground Railroad had a passion for justice and drive to end the practice of slavery —a drive so strong that they risked their lives and jeopardized their own freedom to help enslaved people escape from bondage and keep them safe along the route.

According to some estimates, between 1810 and 1850, the Underground Railroad helped to guide one hundred thousand enslaved people to freedom. As the network grew, the railroad metaphor stuck. “Conductors” guided runaway enslaved people from place to place along the routes. The places that sheltered the runaways were referred to as “stations,” and the people who hid the enslaved people were called “station masters.” The fugitives traveling along the routes were called “passengers,” and those who had arrived at the safe houses were called “cargo.”

Contemporary scholarship has shown that most of those who participated in the Underground Railroad largely worked alone, rather than as part of an organized group. There were people from many occupations and income levels, including former enslaved persons . According to historical accounts of the Railroad, conductors often posed as enslaved people and snuck the runaways out of plantations. Due to the danger associated with capture, they conducted much of their activity at night. The conductors and passengers traveled from safe-house to safe-house, often with 16-19 kilometers (10–20 miles) between each stop. Lanterns in the windows welcomed them and promised safety. Patrols seeking to catch enslaved people were frequently hot on their heels.

These images of the Underground Railroad stuck in the minds of the nation, and they captured the hearts of writers, who told suspenseful stories of dark, dangerous passages and dramatic enslaved person escapes . However, historians who study the Railroad struggle to separate truth from myth . A number of prominent historians who have devoted their life’s work to uncover the truths of the Underground Railroad claim that much of the activity was not in fact hidden, but rather, conducted openly and in broad daylight. Eric Foner is one of these historians. He dug deep into the history of the Railroad and found that though a large network did exist that kept its activities secret, the network became so powerful that it extended the limits of its myth . Even so, the Underground Railroad was at the heart of the abolitionist movement. The Railroad heightened divisions between the North and South, which set the stage for the Civil War .

Media Credits

The audio, illustrations, photos, and videos are credited beneath the media asset, except for promotional images, which generally link to another page that contains the media credit. The Rights Holder for media is the person or group credited.

Production Managers

Program specialists, last updated.

October 19, 2023

User Permissions

For information on user permissions, please read our Terms of Service. If you have questions about how to cite anything on our website in your project or classroom presentation, please contact your teacher. They will best know the preferred format. When you reach out to them, you will need the page title, URL, and the date you accessed the resource.

If a media asset is downloadable, a download button appears in the corner of the media viewer. If no button appears, you cannot download or save the media.

Text on this page is printable and can be used according to our Terms of Service .

Interactives

Any interactives on this page can only be played while you are visiting our website. You cannot download interactives.

Related Resources

- Ask LitCharts AI

- Discussion Question Generator

- Essay Prompt Generator

- Quiz Question Generator

- Literature Guides

- Poetry Guides

- Shakespeare Translations

- Literary Terms

The Underground Railroad

Colson whitehead.

Ask LitCharts AI: The answer to your questions

Welcome to the LitCharts study guide on Colson Whitehead's The Underground Railroad . Created by the original team behind SparkNotes, LitCharts are the world's best literature guides.

The Underground Railroad: Introduction

The underground railroad: plot summary, the underground railroad: detailed summary & analysis, the underground railroad: themes, the underground railroad: quotes, the underground railroad: characters, the underground railroad: symbols, the underground railroad: literary devices, the underground railroad: theme wheel, brief biography of colson whitehead.

Historical Context of The Underground Railroad

Other books related to the underground railroad.

- Full Title: The Underground Railroad

- When Written: 2011-2016

- Where Written: New York, USA

- When Published: 2016

- Literary Period: 21st century African-American historical fiction

- Genre: Neo-slave narrative

- Setting: Several states in America in the year 1850, including Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Indiana

- Climax: When Elijah Lander delivers his speech and it is interrupted by a white gang who destroy Valentine farm

- Antagonist: Arnold Ridgeway

- Point of View: Third-person narrator

Extra Credit for The Underground Railroad

Coming to the small screen. In March 2017 Amazon announced the production of a mini-series based on The Underground Railroad , directed by Oscar-winning director Barry Jenkins.

Real pieces of history. The first four runaway slave ads featured in the novel are taken word-for-word from real 19th century newspapers. The only one that Whitehead wrote himself is the last one, Cora’s.

- Quizzes, saving guides, requests, plus so much more.

- Skip to global NPS navigation

- Skip to the main content

- Skip to the footer section

Exiting nps.gov

Harriet tubman and the underground railroad.

“When I found I had crossed that line, I looked at my hands to see if I was the same person. There was such a glory over everything; the sun came like gold through the trees, and over the fields, and I felt like I was in Heaven.” Harriet Tubman

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, The New York Public Library.

You Might Also Like

- harriet tubman national historical park

- harriet tubman underground railroad national historical park

- harriet tubman

- underground railroad

Harriet Tubman National Historical Park , Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Historical Park

Last updated: March 11, 2017

Find anything you save across the site in your account

The Perilous Lure of the Underground Railroad

The crate arrived, via overland express, one spring evening in 1849. Three feet long, two feet wide, and two and a half feet deep, it had been packed the previous morning in Richmond, Virginia, then carried by horse cart to the local office of the Adams Express Company. From there, it was taken to the railroad depot, loaded onto a train, and, on reaching the Potomac, transferred to a steamer, where, despite its label— THIS SIDE UP WITH CARE —it was placed upside down until a tired passenger tipped it over and used it as a seat. After arriving in the nation’s capital, it was loaded onto a wagon, dumped out at the train station, loaded onto a luggage car, sent on to Philadelphia, unloaded onto another wagon, and, finally, delivered to 31 North Fifth Street. The person to whom the box had been shipped, James Miller McKim, was waiting there to receive it. When he opened it, out scrambled a man named Henry Brown: five feet eight inches tall, two hundred pounds, and, as far as anyone knows, the first person in United States history to liberate himself from slavery by, as he later wrote, “getting myself conveyed as dry goods to a free state.”

McKim, a white abolitionist with the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society, had by then been working for the Underground Railroad for more than a decade, and he was awed by the courage and drama of Brown’s escape, and of others like it. In an article he wrote some years later, he predicted that future generations of Americans would come to share his emotions:

Now deemed unworthy of the notice of any, save fanatical abolitionists, these acts of sublime heroism, of lofty self-sacrifice, of patient martyrdom, these beautiful Providences, these hair-breadth escapes and terrible dangers, will yet become the themes of the popular literature of this nation, and will excite the admiration, the reverence and the indignation of the generations yet to come.

It did not take long for McKim’s prediction to come true. The Underground Railroad entered our collective imagination in the eighteen-forties, and it has since been a mainstay of both national history and local lore. But in the past decade or so it has surged into “the popular literature of this nation”—and the popular everything else, too. This year alone has seen the publication of two major Railroad novels, including Oprah’s first book-club selection in more than a year, Colson Whitehead’s “The Underground Railroad” (Doubleday). On TV, the WGN America network aired the first season of “Underground,” which follows the fates of a group of slaves, known as the Macon Seven, who flee a Georgia plantation.

Nonfiction writers, too, have lately returned to the subject. In 2004, the Yale historian David Blight edited “Passages to Freedom,” an anthology of essays on the Underground Railroad. The following year, Fergus Bordewich published “Bound for Canaan,” the first national history of the Railroad in more than a century. And last year, Eric Foner, a historian at Columbia, published “Gateway to Freedom,” about the Railroad’s operations in New York City. Between 1869 and 2002, there were two adult biographies of Harriet Tubman, the Railroad’s most famous “conductor”; more than four times as many have been published since then, together with a growing number of books about her for children and young adults—five in the nineteen-seventies, six in the nineteen-eighties, twenty-one in the nineteen-nineties, and more than thirty since the turn of this century. An HBO bio-pic about Tubman is in development, and earlier this year the U.S. Treasury announced that, beginning in the next decade, she will appear on the twenty-dollar bill.

Other public and private entities have likewise taken up the cause. Since 1998, the National Park Service has been working to create a Network to Freedom, a system of federally designated, locally managed Underground Railroad sites around the country. The first national museum dedicated to the subject, the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center, opened in Cincinnati in 2004, and next March the Park Service will inaugurate its first Railroad-related national monument: the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad State Park, in Cambridge, Maryland, near Tubman’s birthplace.

This outpouring of interest suggests that we have collectively caught on to what McKim long ago understood: that the stories of those who fled slavery and those who helped them to freedom are among the most moving in our nation’s history. It was McKim’s hope that these stories would excite our admiration, reverence, and indignation, and they do. But, as more recent work has made clear, they should also incite our curiosity and skepticism: about how the Underground Railroad really worked, why stories about it so consistently work on us, and what they teach us—or spare us from learning—about ourselves and our nation.

No one knows who coined the term. Some ascribe it to a thwarted slave owner, others to a runaway slave. It first appeared in print in an abolitionist newspaper in 1839, at the end of a decade when railways had come to symbolize prosperity and progress, and three thousand miles of actual track had been laid across the nation. Frederick Douglass used the term in his 1845 autobiography—where he laments that indiscreet abolitionists are turning it into “an upperground railroad”—and Harriet Beecher Stowe used it in 1852, in “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” when one slave-catcher cautions another against delaying pursuit of a fugitive “till the gal’s been carried on the underground line.” By the following year, the Times was reporting that the term had “come into very general use to designate the organized arrangements made in various sections of the country, to aid fugitives from slavery.”

Seldom has our national lexicon acquired a phrase so appealing to the imagination, or so open to misinterpretation. In his new novel, Colson Whitehead exploits both those qualities by doing knowingly what nearly every young child first learning our history does naïvely: taking the term “Underground Railroad” literally. His protagonist, a teen-age girl named Cora, flees the Georgia plantation where she was born into slavery and heads north on a series of rickety subterranean trains—one- or two-car numbers, driven by actual conductors and reached via caves or through trapdoors in buildings owned by sympathetic whites.

Whitehead has a taste for fantastical infrastructure, first revealed via the psychically active elevators in his brilliant début novel, “The Intuitionist.” Those elevators were the perfect device—mingling symbolic resonance with Marvel Comics glee, absolved of improbability by the particularity and force of Whitehead’s imagination. In “The Underground Railroad,” he more or less reverses his earlier trick. Rather than imbue a manufactured box with mystery, he turns our most evocative national metaphor into a mechanical contraption. It is a clever choice, reminding us that a metaphor never got anyone to freedom. Among his other concerns in this book, Whitehead wants to know what does: how the Underground Railroad really worked, and at what cost, and for whom.

Those questions were first asked in an extensive and systematic way by an Ohio State University historian named Wilbur Siebert. In the last decade of the nineteenth century, when many parents of the Civil War dead were still alive to grieve for their children and former slaves still outnumbered freeborn African-Americans, Siebert began contacting surviving abolitionists or their kin and asking them to describe their efforts to aid fugitives from slavery. The resulting history, published in 1898 and entitled “The Underground Railroad from Slavery to Freedom,” depicted a network of more than three thousand anti-slavery activists, most of them white, who helped ferry largely anonymous runaways to freedom. That history has been diffusing through the culture ever since, gathering additional details along the way and profoundly shaping our image of the Underground Railroad. In that image, a clandestine organization of abolitionists—many of them Quaker or otherwise motivated by religious ideals—used covert methods (tunnels, trapdoors, concealed passageways) and secret signals (lanterns set in windows, quilts hung on laundry lines) to help convey enslaved African-Americans to freedom.

That story, like so many that we tell about our nation’s past, has a tricky relationship to the truth: not quite wrong, but simplified; not quite a myth, but mythologized. For one thing, far from being centrally organized, the Underground Railroad was what we might today call an emergent system: it arose through the largely unrelated actions of individuals and small groups, many of whom were oblivious of one another’s existence. What’s more, even the most active abolitionists spent only a tiny fraction of their time on surreptitious adventures with packing crates and the like; typically, they carried out crucial but banal tasks like fund-raising, education, and legal assistance. And while fugitives did often need to conceal themselves en route to freedom, most of their hiding places were mundane and catch-as-catch-can—haylofts and spare bedrooms and swamps and caves, not bespoke hidey-holes built by underground engineers. As for the notion that passengers on the Underground Railroad communicated with one another by means of quilts: that idea originated, without any evident basis, in the eighties (the nineteen -eighties).

The putative role of textiles and architecture in antebellum activism doesn’t matter that much, but other distortions in Siebert’s story do. No one disputes that white abolitionists were active in the Underground Railroad, but later scholars argued that Siebert had exaggerated both their numbers and their importance, while downplaying or ignoring the role played by African-Americans. Among religious sects, for example, the Quakers generally receive the most credit for resisting slavery, with secondary acknowledgment going to the wave of evangelical Christianity that spread across the United States during the first half of the nineteenth century, in the movement known as the Second Great Awakening. Yet scant mainstream attention goes to the African Methodist Episcopal Church, which was established in 1816, in direct response to American racism and the institution of slavery, and played at least as crucial a role in raising money, aiding fugitives, and helping former slaves who had found their way to freedom make a new life.

This lopsided awareness holds not only for institutions but for individuals. Many people know of William Lloyd Garrison, one of the country’s leading white anti-slavery activists, while almost no one knows about the black abolitionist William Still—one of the most effective operators and most important historians of the Underground Railroad, whose book about it, published a quarter of a century before Siebert’s, was based on detailed notes he kept while helping six hundred and forty-nine fugitives onward toward freedom. Likewise, more people know the name of Levi Coffin, a white Midwestern Quaker, than that of Louis Napoleon, a freeborn black abolitionist, even though both risked their lives to help thousands of fugitives to safety.

Link copied

This allocation of credit is inversely proportional to the risk that white and black anti-slavery activists faced. It took courage almost everywhere in antebellum America to actively oppose slavery, and some white abolitionists paid a price. A few were killed; some died in prison; others, facing arrest or worse, fled to Canada. But these were the exceptions. Most whites faced only fines and the opprobrium of some in their community, while those who lived in anti-slavery strongholds, as many did, went about their business with near-impunity.

Black abolitionists, by contrast, always put life and liberty on the line. If caught, free blacks faced the possibility of being illegally sold into slavery, while fugitives turned agents faced potential reënslavement, torture, and murder. Harriet Tubman is rightly famous for how boldly she faced those risks: first when she fled slavery herself; then during the roughly twenty return trips she made to the South to help bring others to freedom; and, finally, during the war, when she accompanied Union forces into the Carolinas, where they disrupted supply lines and, under her direction, liberated some seven hundred and fifty slaves. By then, slaveholders in her home state of Maryland were clamoring for her capture, dead or alive, and, in the words of her first biographer, publicly debating “the different cruel devices by which she would be tortured and put to death.”

Tubman, of course, is the one black conductor on the Underground Railroad whose fame is commensurate with her work. She is also the only black conductor most people know—though William Still’s reputation may be on the rise, courtesy of his small but compelling role in the uneven but often excellent TV series “Underground.” Still, while white abolitionists remain statistically overrepresented in stories about the Underground Railroad, the recent set suggests that, more than a century after Siebert, the balance may finally be shifting. “Who built it?” one of Whitehead’s fugitives asks, on first reaching a station on the Underground Railroad and peering down a tunnel where iron tracks disappear into darkness. “Who builds anything in this country?” the agent answers.

The fugitive-slave narrative presents a curious paradox. In terms of content, it describes one of the darkest eras of American history; in terms of form, it is, in a way, the perfect American story. Its plot is the central one of Western literature: a hero goes on a journey. Its protagonist obeys the dictates of her conscience instead of the dictates of the state, thereby satisfying our national appetite for righteous outlaws. And its narrative arc bends in our preferred direction: from Tubman to Katniss Everdeen, from “The Shawshank Redemption” to Cheryl Strayed, we adore stories of individuals who fight their way to actual or psychological freedom.

Although such heroes make their journeys under duress, fugitive-slave stories are also a form of travel narrative. And, while in real life fugitives ran in every imaginable direction and were often caught or forced to turn back or died en route, in our stories the direction of travel is more nearly uniform. On the Underground Railroad, geography is plot: the South represents iniquity and bondage, the North enlightenment and freedom.

Whitehead, a canny storyteller, makes use of this narrative tradition in “The Underground Railroad,” while also considerably complicating it. Freedom is illusory in his novel, and iniquity unbound by latitude, but he knows that the story of slavery is fundamentally the story of America, and he uses Cora’s journey to observe our nation, from an upper-crust mixed-race family in Boston to a farming community in Indiana. Some of the finest parts of the novel involve the effort to make sense of a new place—whether through the tiny attic window from which Cora studies the cultural, political, and natural landscape of a North Carolina town or on the long, strange wagon ride she takes through a Tennessee landscape devastated by wildfire. As in “Lolita,” the moral crisis is so consuming that it’s easy to miss the journey—but the journey is the essence of this novel.

Indeed, the most effective liberties that Whitehead takes are not with Cora’s mode of transport but with the terrain through which she travels. Station by station, he builds a physical landscape out of the chronology of African-American history. Cora’s northward journey first lands her in South Carolina, where what initially seems to be a policy of paternalistic benevolence toward blacks turns out to mask a series of disturbing medical interventions: a kind of early, statewide Tuskegee experiment. From there, she moves on to North Carolina, which has implemented, to genocidal ends, the ideals of the American Colonization Society—a real organization and social movement, evoked but unmentioned by Whitehead, that sought to end slavery and return all blacks to Africa, not least to make real the enduring fantasy of a white America. In Whitehead’s fictional version, new race laws forbid blacks to enter the state, and those caught within its borders are tortured, murdered, and left hanging on trees as a warning to others. North Carolina, one character observes, has succeeded in abolishing slavery. “On the contrary,” another corrects him. “We abolished niggers.”

As all this suggests, Cora is trying to escape from much more than a plantation. In the temporally elastic landscape through which she flees, it is slavery, as much as the slave-catcher, that is pursuing her, and anyone alive in today’s America knows that she will never entirely outrun it. Indeed, at times Cora seems to be already traversing a future bereft of full freedom—the landscape blighted by proto-Jim Crow, her journey a private Great Migration. Behind the slave-catcher we can almost glimpse the police officer misusing lethal force; behind the manacles on the walls of a train depot, the bars of mass incarceration.

Still, for all the liberties that “The Underground Railroad” takes with the past, they have nothing on those in “Underground Airlines” (Mulholland Books), by the novelist and playwright Ben Winters, best known for his 2009 parody, “Sense and Sensibility and Sea Monsters.” (As it happens, Colson Whitehead’s previous book was about zombies.) Winters posits an alternate history in which the Civil War was averted and slavery, never abolished on the national level, persists into our own era, in what are called the Hard Four: Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and the Carolinas, which together hold three million people in bondage. The protagonist, known mostly as Victor, is a fugitive slave who, after being apprehended, makes a Faustian bargain: in exchange for keeping his freedom, he agrees to work for the U.S. Marshals Service to catch other runaways.

When “Underground Airlines” opens, Victor is working his two-hundred-and-tenth case, trying to track down a mysterious fugitive, nicknamed Jackdaw, who has run away from an Alabama textile plantation. To find him, Victor must infiltrate the national anti-slavery network known as the Underground Airlines—not a literal entity here but “the root of a grand, extended metaphor,” now updated: airport security, gate agents, connecting flights, baggage handlers. “The Airlines flies on the ground, in package trucks and unmarked vans and stolen tractor-trailers,” Winters writes. “It flies in the illicit adjustment of numbers on packing slips, in the suborning of plantation guards and the bribing of border security agents, in the small arts of persuasion: by threat or cashier’s check or blow job.”

Winters, also the author of several mysteries, is working partly in the genre of the hardboiled detective novel; Victor is a classic noir antihero, whose self-interested amorality cloaks a troubled heart. But “Underground Airlines” also belongs to the tradition of counterfactual secession stories, à la Harry Turtledove’s “The Guns of the South” and MacKinlay Kantor’s “If the South Had Won the Civil War.” Such alternate histories run the risk of piling on textbooky details in the interest of proving the credibility of events that never happened, but Winters gets the balance right. He is careful to set up a plausible case for how history shifted off-kilter (Lincoln is assassinated before an armed conflict can break out; Congress, in grief and chaos, jams through a compromise that preserves both the Union and slavery), and he paints a convincing picture of what fugitive life would look like in our own era. (Homeland Security has a division called Internal Border and Regulation, the slave-catchers’ most fearsome tools are technological, and plantation overseers are supplied by private contractors.) But he is ultimately far more interested in the political, intellectual, and moral compromises that people make in order to live in the presence of, and sustain the existence of, legal bondage. Like Whitehead, though in a strikingly different way, he wants to get us to see the past in the present—the innumerable ways that we still live in a world made by slavery.

The first train ride that Cora takes in “The Underground Railroad” begins just below a farmhouse in rural Georgia and ends underneath a tavern in South Carolina. Whitehead, who knows his history, sneaks a little asterisk into the escape. “It was commonly held,” he writes, “that the underground railroad did not operate this far south.”

It did not. Contrary to a claim made by Siebert and subsequently reflected in myriad popular representations, the Underground Railroad didn’t lead “from the Southern states to Canada.” In fact, with very rare exceptions, it didn’t operate below the Mason-Dixon Line at all. Aside from a few outposts in border states, the Railroad was a Northern institution. As a result, for the roughly sixty per cent of America’s slaves who lived in the Deep South in 1860, it was largely unknown and entirely useless.

These are inconvenient facts for those who like to locate America’s antebellum conscience in the North. Had that region really been so principled, it wouldn’t have needed a clandestine system to convey fugitives beyond its borders to a foreign nation. Instead, while slavery itself was against the law in the North, upholding the institution of slavery was the law. As a nation, the United States regarded it as a legitimate practice, respected the right of white Southerners to own other human beings, and expressed that respect in laws that governed not half but all of the land.

This was a moral disaster for our country, and a terror for fugitive slaves. The obligation to return them to their owners was enshrined in the Constitution, then further codified in 1793, and in the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850—which, as Foner notes, was among the most draconian laws ever enacted in this nation. It rendered impotent any Northern ordinances designed to protect fugitives; compelled citizens to assist in capturing them; set harsh civil and criminal punishments for failing to do so; created a legal document ordering a specific fugitive to be returned to his or her master that could not be challenged in any court of law; and established a fee system whereby officials adjudicating fugitive-slave cases earned ten dollars if they decided in favor of the owner and five if they decided for the slave.

“We could see no spot, this side of the ocean, where we could be free,” Frederick Douglass wrote in his autobiography: fugitives themselves knew that they were only marginally better off in the ostensibly free state of Ohio than across the border in Kentucky, only marginally safer in Maine or Michigan or Wisconsin than in Maryland and North Carolina and Washington, D.C. Outside of scattered pockets in upstate New York, Massachusetts, and the Midwest, moral opposition to slavery was not the norm above the Mason-Dixon Line, and fugitives were not exactly welcomed with open arms. In 1858, an editorial in a Vermont newspaper demanded that “a log must be laid across the track of the underground railroad,” and went on to argue, in terms that echo today’s debates over refugees, for the immediate cessation of “the illegal introduction of colored persons in the free states” to “prevent a large yearly increase of that class of population which is hanging like a millstone around the neck of our industrial progress.” Several ostensibly free states, including Illinois and Indiana, did just that, passing laws that prohibited free blacks from settling inside their borders. On the eve of the Civil War, the mayor of New York proposed that the city secede from the Union to protect its economic relationship with the South.

We should not be surprised, then, that most people who slipped the bonds of slavery did not look north. In fact, despite its popularity today, the Underground Railroad was perhaps the least popular way for slaves to seek their freedom. Instead, those who fled generally headed toward Spanish Florida, Mexico, the Caribbean, Native American communities in the Southeast, free-black neighborhoods in the upper South, or Maroon communities—clandestine societies of former slaves, some fifty of which existed in the South from 1672 until the end of the Civil War. Together, such runaways likely outnumbered those who, aided by Northern abolitionists, made their way to free states or to Canada.

Moreover, most slaves who sought to be free didn’t run at all. Instead, they chose to pursue liberty through other means. Some saved up money and purchased their freedom. Others managed to earn a legal judgment in their favor—for instance, by having or claiming to have a white mother (beginning in Colonial times, slave status, like Judaism, passed down through the maternal line), or by claiming to have been manumitted. In “Slaves Without Masters,” the historian Ira Berlin quotes an irate man addressing a neighbor who had freed his slaves. “I will venture to assert,” he complained, “that a vastly greater number of slave people have passed and are passing now as your free men than you ever owned.”

The more you try to put the Underground Railroad in context, in other words, the tinier it seems. Most runaways did not head north, and most slaves who sought their liberty did not run away. And then there is the largest and most important context, the one we least like to acknowledge: from the vast, vicious, legally permitted, fiercely defended enterprise that was American slavery, almost no one ever escaped at all.

No one knows for sure how many enslaved Americans escaped with the help of the Underground Railroad. Foner estimates that, between 1830 and 1860, some thirty thousand fugitives passed through its networks to freedom. Other calculations suggest that the total number is closer to fifty thousand—or, at the highest end, twice that many.

What we do know for sure is this: in 1860, the number of people in bondage in the United States was nearly four million. By then, slavery in this country was more than two hundred years old, and although estimates are hard to come by, perhaps twice that many million African-Americans had lived their lives in chains. Most accounts of fugitive slaves do not invoke those numbers, and most Americans do not know them. The Underground Railroad is a numerator without a denominator.

The problem, then, is not the stories we tell; it’s the stories we don’t tell. In 1988, after her own story about a runaway slave, “Beloved,” won the Pulitzer Prize, Toni Morrison described the scope of this silence. “There is no place you or I can go, to think about or not think about, to summon the presences of or recollect the absences of slaves,” Morrison said. “There is no suitable memorial or plaque or wreath or wall or park or skyscraper lobby. There’s no three-hundred-foot tower. There’s no small bench by the road. There is not even a tree scored, an initial that I can visit or you can visit in Charleston or Savannah or New York or Providence, or, better still, on the banks of the Mississippi.”

In the decades since Morrison spoke, all of that has only barely begun to change. We have told a few more stories, organized a few more exhibits, planned a few new museums, including one devoted to all of African-American history, opening next month on the National Mall, in Washington, D.C., and the privately funded Whitney Plantation, in Louisiana, the first to be wholly dedicated to slavery. Yet, more than a hundred and fifty years after the Emancipation Proclamation, you still will not find, anywhere in our country, a federal monument to the millions of people whom we, as a nation, kept in bondage. To put that omission in perspective, there are more than eighty national parks and monuments and countless other federal memorials commemorating the Civil War. That war lasted four years. Slavery lasted two and a half centuries.

Until the very end of that time, most white Americans, North and South, either actively fought to maintain the institution of slavery or passively sustained and benefitted from it. Only a small fraction had the moral clarity to recognize its evils without caveat or compromise, and, before the war broke out, very few did anything to directly challenge it. Fewer still took the kind of action that later made agents of the Underground Railroad such widely admired figures. Exactly how few is hard to know, but most historians now dismiss Siebert’s original tally of three thousand as considerably exaggerated, compiled as it was from post-hoc accounts. Eric Foner, making the best of difficult data, suggests that, across the country and throughout the duration of slavery, the number of white Americans who regularly aided fugitives was in the hundreds.

Only after the fact—when it no longer required vision or courage or personal sacrifice; when the Civil War was over and the effort to distance ourselves from the moral stain of slavery had begun—did large numbers of white Americans grow interested in being part of the story of African-American liberation. That interest led to the first major renovation and expansion of our favorite piece of mythic infrastructure, a project that began with the work of Wilbur Siebert. A similar expansion is under way in our own times. Much of it is welcome: over all, the recent crop of underground stories feature more black agency, fewer white saviors, greater attentiveness not only to runaways but to what they were running from. The boom in public exhibitions and institutions honoring Railroad sites, however, in part reflects the fact that it has now become not only morally but also economically advantageous to be associated with the Underground Railroad; in contrast to even twenty years ago, significant numbers of people will pay to visit such places. A similar trend is appearing in private real estate. As the historian David Blight wondered, “Is there a realtor in the Northern or border states selling old or historic homes, largely to white people, who has not contemplated the market value of space that might have been used in the nineteenth century to hide black people who were fugitives from slavery?”

That desire to literally own part of the story of the Underground Railroad is extremely widespread and is much of what makes it so popular in the first place. In the entire history of slavery, the Railroad offers one of the few narratives in which white Americans can plausibly appear as heroes. It is also one of the few slavery narratives that feature black Americans as heroes—which is to say, one of the few that emphasize the courage, intelligence, and humanity of enslaved African-Americans rather than their subjugation and misery. By rights, the shame of oppression should fall exclusively on the oppressor, yet one of the most insidious effects of tyranny is to shift some of that emotional burden onto the oppressed. The Underground Railroad relieves black and white Americans alike, although in very different ways, of the burden of feeling ashamed.

White Americans also feature as villains in Underground Railroad stories, of course, but often in ways that minimize over-all white responsibility. Because the stories focus on the fugitive, much of the viciousness of slavery is displaced onto the slave-catcher—an odious figure, to be sure, but ultimately an epiphenomenon of an odious system. Some recent Underground Railroad stories manage to resist that figure’s allure. Victor, the slave-catcher in “Underground Airlines,” is interesting not only because he is a former fugitive but because he is an essentially bureaucratic figure—one of many such people employed by the federal government to navigate and enforce the byzantine system by which slavery endures. But Arnold Ridgeway, the slave-catcher in Colson Whitehead’s novel, and August Pullman, in “Underground,” are Ahab-like characters, privately and demonically obsessed with tracking down specific fugitives. They both come off as irrationally committed to the hunt (and, like all supervillains, irrationally unkillable), and both risk locating the atrocities of slavery in individual pathology.

In reality, and notwithstanding the viciousness of its many enforcers, slavery was institutional. The Underground Railroad, by contrast, was personal: a scattering of private citizens, acting on conscience, and connected for the most part only as the constellations are—from a great distance, by their light. They have earned our admiration and reverence, as McKim knew they would, and we have made much of their few stories, in part for suspect reasons: because they assuage our conscience, distract us from tragedy with thrilling adventures, give us a comparatively comfortable place to rest in a profoundly uncomfortable past.

Yet there are also deep and honorable reasons that we are drawn to these stories: they show us the best parts of ourselves and articulate our finest vision of our nation. When Congress approved funding for the Network to Freedom, it noted, correctly, that “the Underground Railroad bridged the divides of race, religion, sectional differences, and nationality; spanned state lines and international borders; and joined the American ideals of liberty and freedom expressed in the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution to the extraordinary actions of ordinary men and women working in common purpose to free a people.”

It is to our credit if these are the Americans to whom we want to trace our moral genealogy. But we should not confuse the fact that they took extraordinary actions with the notion that they lived in extraordinary times. One of the biases of retrospection is to believe that the moral crises of the past were clearer than our own—that, had we been alive at the time, we would have recognized them, known what to do about them, and known when the time had come to do so. That is a fantasy. Iniquity is always coercive and insidious and intimidating, and lived reality is always a muddle, and the kind of clarity that leads to action comes not from without but from within. The great virtue of a figurative railroad is that, when someone needs it—and someone always needs it—we don’t have to build it. We are it, if we choose. ♦

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction & Top Questions

Abolition work

After the civil war.

- What caused the American Civil War?

- Who won the American Civil War?

- Who were the most important figures in the American Civil War?

- Why are Confederate symbols controversial?

Harriet Tubman

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Spartacus Educational - Biography of Harriet Tubman

- American Battlefield Trust - Biography of Harriet Tubman

- Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Byway - Harriet Tubman

- BlackPast - Biography of Harriet Ross Tubman

- HistoryNet - Harriet Tubman

- National Museum of African American History and Culture - Harriet Tubman: Life, Liberty and Legacy

- Official Site of Harriet Tubman Museum

- Social Welfare History Project - Biography of Harriet Tubman

- National Women's History Museum - Biography of Harriet Tubman

- Women and the American Story - Life Story: Harriet Tubman

- Harriet Tubman - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- Harriet Tubman - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

Who was Harriet Tubman?

Harriet Tubman escaped from slavery in the South to become a leading abolitionist before the American Civil War . She led hundreds of enslaved people to freedom in the North along the route of the Underground Railroad .

What were Harriet Tubman’s accomplishments?

Harriet Tubman is credited with conducting upward of 300 enslaved people along the Underground Railroad from the American South to Canada. She showed extraordinary courage, ingenuity, persistence, and iron discipline.

What did Harriet Tubman do to change the world?

In addition to leading more than 300 enslaved people to freedom, Harriet Tubman helped ensure the final defeat of slavery in the United States by aiding the Union during the American Civil War . She served as a scout and a nurse, though she received little pay or recognition.

Harriet Tubman (born c. 1820, Dorchester county, Maryland, U.S.—died March 10, 1913, Auburn, New York) was an American bondwoman who escaped from slavery in the South to become a leading abolitionist before the American Civil War . She led dozens of enslaved people to freedom in the North along the route of the Underground Railroad —an elaborate secret network of safe houses organized for that purpose.

Born into slavery, Araminta Ross later adopted her mother’s first name , Harriet. At about age five she was first hired out to work, initially serving as a nursemaid and later as a field hand, a cook, and a woodcutter. When she was about 12 years old, she reportedly refused to help an overseer punish another enslaved person, and she suffered a severe head injury when he threw an iron weight that struck her; she subsequently suffered seizures throughout her life. About 1844 she married John Tubman, a free Black man.

In 1849, on the strength of rumors that she was about to be sold, Tubman fled to Philadelphia , leaving behind her husband (who refused to leave), parents, and siblings. In December 1850 she made her way to Baltimore , Maryland , whence she led her niece Kessiah Jolley and her niece’s two children, James Alfred and Araminta, to freedom. That journey was the first of some 13 increasingly dangerous forays into Maryland in which, over the next decade, she conducted about 70 fugitive enslaved people along the Underground Railroad to Canada.(Owing to exaggerated figures in Sara Bradford’s 1868 biography of Tubman, it was long held that Tubman had made about 19 journeys into Maryland and guided upward of 300 people out of enslavement.) Tubman displayed extraordinary courage, persistence, and iron discipline , which she enforced upon her charges. If anyone decided to turn back—thereby endangering the mission—she reportedly threatened them with a gun and said, “You’ll be free or die.” She also was inventive, devising various strategies to better ensure success. One such example was escaping on Saturday nights, since it would not appear in newspapers until Monday. The railroad’s most famous conductor, Tubman became known as the “Moses of her people.” It has been said that she never lost a fugitive she was leading to freedom.

Rewards were offered by slaveholders for Tubman’s capture, while Abolitionists celebrated her courage. John Brown , who consulted her about his own plans to organize an antislavery raid of a federal armory in Harpers Ferry , Virginia (now in West Virginia ), referred to her as “General” Tubman. About 1858 she bought a small farm near Auburn , New York , where she placed her aged parents (she had brought them out of Maryland in June 1857) and herself lived thereafter. From 1862 to 1865 she served as a scout, as well as nurse and laundress, for Union forces in South Carolina during the Civil War . For the Second Carolina Volunteers, under the command of Col. James Montgomery, Tubman spied on Confederate territory. When she returned with information about the locations of warehouses and ammunition, Montgomery’s troops were able to make carefully planned attacks. For her wartime service Tubman was paid so little that she had to support herself by selling homemade baked goods.

Following the Civil War Tubman settled in Auburn and began taking in orphans and older adults, a practice that eventuated in the Harriet Tubman Home for Aged and Indigent Negroes. Tubman was a patient of the home from 1911 until her death in 1913, staying in a building known as John Brown Hall. The home later attracted the support of former abolitionist comrades and the citizens of Auburn, and it continued in existence until the early 1920s. Tubman also became involved in various other causes, including women’s suffrage . In the late 1860s and again in the late ’90s she applied for a federal pension for her work during the Civil War. Some 30 years after her service a private bill providing for $20 monthly was passed by Congress.

The Underground Railroad

By colson whitehead, the underground railroad essay questions.

In your opinion, why does Colson Whitehead make the Underground Railroad a literal railroad? What function does this play in the novel?

The physical reality of a literal railroad amplifies the colossal effort of those who used the real Underground Railroad. Cora dwells on the immensity of the labor it must have took to build the railroad. Thousands of former slaves undertook back-breaking work, carving tunnels out of mountains, digging holes in the ground underneath all of America. The labor of others, she thinks, is redemptive; with it, they have been transformed, and without it, she would never be free. Thus the transformation of the Railroad into a literal engine gives Whitehead the opportunity to directly commemorate the courage of the real men and women in history who operated the network and used it to flee.

How do different characters regard the American Dream in the novel?

For Ridgeway, both the founding principle and the driving engine of America are comprised of a simple principle: if you steal property and keep it, it is yours. This brutal, stable reality is the American Dream. In contrast, Elijah Lander describes the American Dream is a shifting uncertainty, in fact a grand “delusion.” These are perhaps the two opposite poles of belief in the central myths of America. Perhaps Whitehead's point is made by the protagonist, Cora, who oscillates somewhere in the middle. Sometimes she she thinks America is just “a ghost in the darkness,” nothing real at all. At other times, she is unsure, “stirred” by the idea of expansion and progress. In the end, she is aligned with those Americans seeking to cash in on the American Dream, moving out west to reap the rewards of the frontier.

What effect does the structure of the novel's chapters have on the development of the plot?

While being transported in chains through Tennessee, Cora reflects on how the peculiar institution has made her a keeper of lists. In a column in her head, she logs everyone who has impacted her journey, honoring them even as she must move on without them. The novel's structure functions in much the same way. Whitehead alternates between chapters depicting Cora's story, and chapters telling the stories of secondary characters. The first such chapter, giving context for Ajarry's life, functions as an exposition and mood-setting for the entire novel. Later, several characters are featured after their deaths—for example, Ethel, Caesar, and Mabel—and so their chapters function as memorials. Other characters—Ridgeway and Stevens, for instance—provide ideological counterpoints to Cora's story, juxtaposing her struggle with the ideas of white supremacist America. In total, these chapters form a list of characters who have impacted Cora, mimicking the list she keeps in her head.

What role does the character of Mabel have on Cora's story?

In some ways, Mabel is the driving force behind Cora's story. When Mabel escapes the Randall plantation, she leaves behind a vegetable garden that reminds Cora of the promise of freedom. Cora grows to resent her mother for leaving her behind to suffer. Throughout the novel, as she makes her way through a hellish landscape in search of the freedom she believes her mother attained, she pictures Mabel in freedom, perhaps in Canada. Cora's struggle is shaped by Mabel in another way too: Ridgeway, the slave catcher, takes it as a personal insult that he never found and recaptured Mabel. This old grievance drives him to capture Cora at all costs. More than just his job, his pursuit of Cora is a personal and thus much more dangerous vendetta.

In an ironic twist at the end of the novel, however, the narrator reveals that Mabel never made it to freedom. She died on her way back to Cora, in the swamp just outside the Randall plantation. Thus the driving impetus of Cora's story falls apart, and it turns out Cora made her escape all on her own.

How does Ridgeway's character develop over the course of the book?

In the third chapter, Ridgeway's back story describes him as a formidable opponent. Tall, cold-hearted, and extremely violent, he makes the perfect antagonist. As time goes on, however, cracks begin to show in his steely persona. Cora learns the odd story of how he recognized a kindred spirit in a young black slave, Homer, whom he freed and befriended. The relationship between the ten-year-old boy and Ridgeway remains an enigma throughout the novel, but there seems to be clear affection there. Thus the slave catcher is not as hard-hearted as he initially seemed. Ridgeway is then severely diminished by the confrontation with Royal and Red in Tennessee. From that point on, his pursuit of Cora borders on the obsession of a mentally unstable man. When he finally catches up to her for the last time in Indiana, he seems unkempt and disheveled. Thus over the course of the novel, Ridgeway's relentless pursuit of Cora appears to weaken him. He eventually unravels while Cora continues on to freedom.

The Underground Railroad Questions and Answers

The Question and Answer section for The Underground Railroad is a great resource to ask questions, find answers, and discuss the novel.

The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead

Colorism is expressed through the differences in the way that those with lighter skin were treated differently than those with darker skin. Black people with lighter skin were afforded more opportunities, and they were often able to "pass" as...

What are the three cities a former slave escaping from Nashville might pass through to get to Canada?

Though I cannot give you the names of the exact cities, slaves escaping by route of the Underground Railroad from Nashville went through the states of Kentucky and Ohio.

What does fugitive mean?

A fugitive is "a person who has escaped from a place or is in hiding, especially to avoid arrest or persecution."

Study Guide for The Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad study guide contains a biography of Colson Whitehead, literature essays, quiz questions, major themes, characters, and a full summary and analysis.

- About The Underground Railroad

- The Underground Railroad Summary

- Character List

Essays for The Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad essays are academic essays for citation. These papers were written primarily by students and provide critical analysis of The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead.

- Delusion and Reality in The Underground Railroad

- Past and Future Blues: A Comparison of Historical Themes in 'Sonny's Blues' and 'The Underground Railroad'

- Rewriting the Past

- Underground Railroad: The Railroad To The North As A Metaphor For Freedom

Lesson Plan for The Underground Railroad

- About the Author

- Study Objectives

- Common Core Standards

- Introduction to The Underground Railroad

- Relationship to Other Books

- Bringing in Technology

- Notes to the Teacher

- Related Links

- The Underground Railroad Bibliography

Wikipedia Entries for The Underground Railroad

- Introduction

Search The Canadian Encyclopedia

Enter your search term

Why sign up?

Signing up enhances your TCE experience with the ability to save items to your personal reading list, and access the interactive map.

- MLA 8TH EDITION

- Henry, Natasha. "Underground Railroad". The Canadian Encyclopedia , 03 March 2023, Historica Canada . www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/underground-railroad. Accessed 17 September 2024.

- The Canadian Encyclopedia , 03 March 2023, Historica Canada . www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/underground-railroad. Accessed 17 September 2024." href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

- APA 6TH EDITION

- Henry, N. (2023). Underground Railroad. In The Canadian Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/underground-railroad

- The Canadian Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/underground-railroad" href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

- CHICAGO 17TH EDITION

- Henry, Natasha. "Underground Railroad." The Canadian Encyclopedia . Historica Canada. Article published February 07, 2006; Last Edited March 03, 2023.

- The Canadian Encyclopedia . Historica Canada. Article published February 07, 2006; Last Edited March 03, 2023." href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

- TURABIAN 8TH EDITION

- The Canadian Encyclopedia , s.v. "Underground Railroad," by Natasha Henry-Dixon, Accessed September 17, 2024, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/underground-railroad

- The Canadian Encyclopedia , s.v. "Underground Railroad," by Natasha Henry-Dixon, Accessed September 17, 2024, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/underground-railroad" href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

Thank you for your submission

Our team will be reviewing your submission and get back to you with any further questions.

Thanks for contributing to The Canadian Encyclopedia.

Underground Railroad

Article by Natasha Henry-Dixon

Updated by Andrew McIntosh

Published Online February 7, 2006

Last Edited March 3, 2023

The Underground Railroad was a secret network of abolitionists (people who wanted to abolish slavery). They helped African Americans escape from enslavement in the American South to free Northern states or to Canada. The Underground Railroad was the largest anti-slavery freedom movement in North America. It brought between 30,000 and 40,000 fugitives to British North America (now Canada ).

This is the full-length entry about the Underground Railroad. For a plain language summary, please see The Underground Railroad (Plain-Language Summary).

A provision in the 1793 Act to Limit Slavery stated that any enslaved person who reached Upper Canada became free upon arrival. This encouraged a small number of enslaved African Americans in search of freedom to enter Canada, primarily without help. Word that freedom could be had in Canada spread further following the War of 1812 . The enslaved servants of US military officers from the South brought back word that there were free “Black men in red coats” in British North America . ( See The Coloured Corps: Black Canadians and the War of 1812 .) Arrivals of freedom-seekers in Upper Canada increased dramatically after 1850 with the passage of the American Fugitive Slave Act . It empowered slave catchers to pursue fugitives in Northern states.

Organization

The Underground Railroad was created in the early 19th century by a group of abolitionists based mainly in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Within a few decades, it had grown into a well-organized and dynamic network. The term “Underground Railroad” began to be used in the 1830s. By then, an informal covert network to help fugitive slaves had already taken shape.

The Underground Railroad was not an actual railroad and it did not run on railway tracks. It was a complex, clandestine network of people and safe houses that helped persons enslaved in Southern plantations reach freedom in the North. The network was maintained by abolitionists who were committed to human rights and equality. They offered help to fleeing slaves. Their ranks included free Black people, fellow enslaved persons, White and Indigenous sympathizers, Quakers , Methodists , Baptists , inhabitants of urban centre and farmers, men and women, Americans and Canadians.

Symbols and Codes

Railroad terminology and symbols were used to mask the covert activities of the network. This also helped to keep the public and slaveholders in the dark. Those who helped escaping slaves in their journey were called “conductors.” They guided fugitives along points of the Underground Railroad, using various modes of transportation over land or by water. One of the most famous conductors was Harriet Tubman .

The terms “passengers,” “cargo,” “package” and “freight” referred to escaped slaves. Passengers were delivered to “stations” or “depots,” which were safe houses. Stations were located in various cities and towns, known as “terminals.” These places of temporary refuge could sometimes be identified by lit candles in windows or by strategically placed lanterns in the front yard.

Station Masters

Safe houses were operated by “station masters.” They took fugitives into their home and provided meals, a change of clothing, and a place to rest and hide. They often gave them money before sending them to the next transfer point. Black abolitionist William Still was in charge of a station in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He assisted many freedom-seekers in their journey to Canada. He recorded the names of the men, women and children who stopped at his station, including Tubman and her passengers.

Jermain Loguen was another Black station master and leader in the abolitionist movement. He ran a station in Syracuse, New York. He permanently settled there after living freely in Hamilton and St. Catharines , Upper Canada , from 1837 to 1841. Loguen was well known for his public speeches and articles in anti-slavery newspapers . Numerous women were also station masters. Quaker women Lucretia Mott and Laura Haviland, and Henrietta Bowers Duterte, the first Black female undertaker in Philadelphia, are just a few. Many other women also worked with their husbands to operate stations.

Ticket Agents

“Ticket agents” coordinated safe trips and made travel arrangements for freedom-seekers by helping them to contact station masters or conductors. Ticket agents were sometimes people who travelled for a living, perhaps as circuit preachers or doctors. This enabled them to conceal their abolitionist activities. The Belleville -born doctor Alexander Milton Ross, for instance, was an Underground Railroad agent. He used his bird watching hobby as a cover while he travelled through the South telling enslaved people about the network. He even provided them with a few simple supplies to begin their escape. People who donated money or supplies to aid in the escape of slaves were called “stockholders.”

Ways to the Promised Land

The routes that were travelled to get to freedom were called “lines.” The network of routes went through 14 Northern states and two British North American colonies — Upper Canada and Lower Canada . At the end of the line was “heaven,” or “the Promised Land,” which was free land in Canada or the Northern states. “The drinking gourd” referenced the Big Dipper constellation, which points to the North Star — a lodestar for freedom-seekers finding their way north.

The journey was very dangerous. Many made the treacherous voyage by foot. Freedom-seekers were also transported in wagons , carriages, on horses , and in some cases by train. But the Underground Railroad did not only operate over land. Passengers also travelled by boat across lakes , seas and rivers . They often travelled by night and rested during the day.

The Canadian Terminus

An estimated 30,000 to 40,000 freedom seekers entered Canada during the last decades of enslavement in the US. Between 1850 and 1860 alone, 15,000 to 20,000 fugitives reached the Province of Canada . It became the main terminus of the Underground Railroad. The newcomers migrated to various parts of what is now Ontario . This included Niagara Falls , Buxton, Chatham , Owen Sound , Windsor , Sandwich (now part of Windsor), Hamilton , Brantford , London , Oakville and Toronto . They also fled to other regions of British North America such as New Brunswick , Quebec and Nova Scotia . After this mass migration , Black Canadians helped build strong communities and contributed to the development of the provinces in which they lived and worked.

Although out of their jurisdiction, a few bounty hunters crossed the border into Canada to pursue escaped fugitives and return them to Southern owners. The Provincial Freeman newspaper offered a detailed account of one particular case. A slave holder and his agent travelled to Chatham , Upper Canada, which was largely populated by Black persons once enslaved in the US. They were in search of a young man named Joseph Alexander. After their presence was announced, a large crowd of Black members of the community assembled outside the Royal Exchange Hotel. Alexander was among the throng of people and exchanged words with his former owner. He rejected the men’s offer of $100 to accompany them to Windsor. The crowd refused to let the men seize Alexander, and they were forced to leave town. Alexander was left to live in freedom.

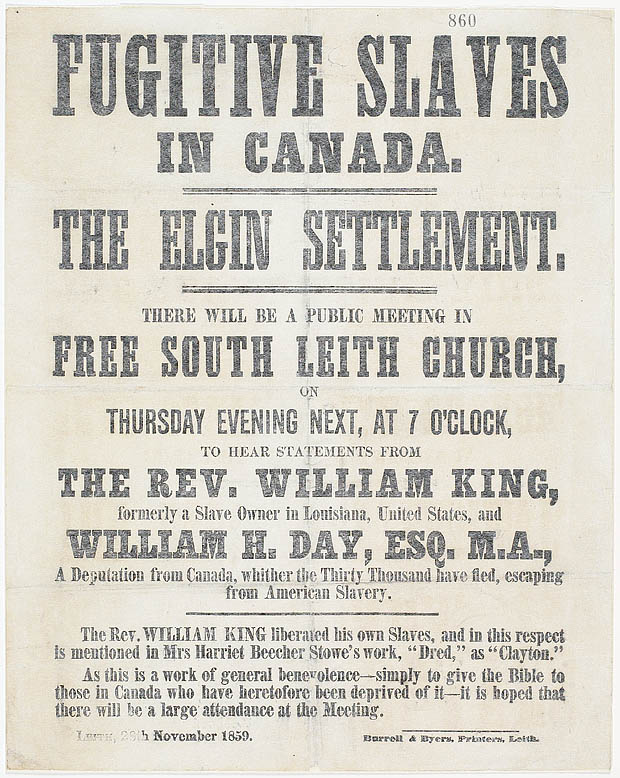

The Underground Railroad operated until the 13th amendment to the US constitution banned enslavement in 1865. Freedom-seekers, free Black people and the descendants of Black Loyalists settled throughout British North America . Some lived in all-Black settlements such as the Elgin Settlement and Buxton Mission, the Queen’s Bush Settlement, and the Dawn Settlement near Dresden , Ontario , as well as Birchtown and Africville in Nova Scotia . Others chose to live in racially integrated communities in towns and cities.

Early African Canadian settlers were productive and innovative citizens. They cleared and cultivated the land, built homes and raised families. Black persons established a range of religious , educational , social and cultural institutions, political groups and community-building organizations. They founded churches, schools, benevolent societies, fraternal organizations and two newspapers . ( See Mary Ann Shadd .)

During the era of the Underground Railroad, Black men and women possessed and contributed a wide range of skills and abilities. They operated various businesses such as grocery stores, boutiques and hat shops, blacksmith shops, a saw company, an ice company, livery stables, pharmacies , herbal treatment services and carpentry businesses, as well as Toronto ’s first taxi company.

Black people were active in fighting for racial equality. Their communities were centres for abolitionist activities. Closer to home, they waged attacks against the prejudice and discrimination they encountered in their daily lives in Canada by finding gainful employment, securing housing, and obtaining an education for their children. Black persons were often relegated to certain jobs because of their skin colour. Many were denied the right to live in certain places due to their race. ( See Residential Segregation .) Parents had to send their children to segregated schools that existed in some parts in Ontario and Nova Scotia. Through publications, conventions and other public events, such as Emancipation Day celebrations, Black communities spoke out against the racial discrimination they faced and aimed to improve society for all.

Wherever African Canadians settled in British North America , they contributed to the socio-economic growth of the communities in which they lived. In their quest for freedom, security, prosperity and human rights , early Black colonists strived to make a better life for themselves, their descendants and their fellow citizens. They left behind an enduring and rich legacy that is evident to this day.

For Black History Month 2022, the Royal Canadian Mint issued a silver coin designed by artist Kwame Delfish to commemorate the Underground Railroad.

See also: Underground Railroad (Plain Language Summary) ; Black Enslavement in Canada (Plain Language Summary) ; Chloe Cooley and the Act to Limit Slavery in Upper Canada ; Slavery Abolition Act, 1833 ; Anti-Slavery Society of Canada ; Josiah Henson ; Albert Jackson ; Richard Pierpoint ; Editorial: Black Female Freedom Fighters .

Black History in Canada Education Guide

- Black Canadians

- Black History

- Enslavement

- underground railroad

Further Reading

Adrienne Shadd, Afua Cooper, Karolyn Smardz Frost, The Underground Railroad, Next Stop Toronto! (2009)

Karolyn Smardz Frost, I’ve Got a Home in Glory Land (2007)

Barbara Greenwood, The Last Safe House: A Story of the Underground Railroad (1998)

Rona Arato, Working for Freedom: the Story of Josiah Henson (2009)

Barbara Smucker, Underground to Canada (1978, rev. 2003).

Karleen Bradford, Dear Canada: A Desperate Road to Freedom: The Underground Railroad Diary of Julia May Jackson (2012)

External Links

Up From Slavery Author Bryan Walls provides a vivid account of his ancestors’ harrowing escape from enslavement along the Underground Railroad. A University of Toronto website.

From Slavery to Settlement Historical accounts and key documents relating to the abolition of enslavement and the establishment of Black settlements in Ontario. From Archives Ontario.

Ontario Black History Society Informative online resource about Black Canadian history and heritage.

Tracks to Freedom Travel down the interactive Tracks to Freedom website to learn about the people and events associated with the legendary Underground Railroad. From the Ottawa Citizen.

Underground Railroad Watch the Heritage Minute about the "underground railroad" from Historica Canada. See also related online learning resources.

The Underground Railroad: Next Stop, Toronto! This nicely illustrated book offers new insights into the life and times of 19th century Toronto and the intriguing history and heritage of Toronto’s Black community. From indigo.ca.

North to Freedom Noted historian and human rights advocate Daniel Hill talks about the importance of the Underground Railway in this 1979 CBC Radio clip.

Recommended

Chloe cooley, black enslavement in canada.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Harriet Tubman

By: History.com Editors

Updated: February 20, 2024 | Original: October 29, 2009

Harriet Tubman was an escaped enslaved woman who became a “conductor” on the Underground Railroad, leading enslaved people to freedom before the Civil War, all while carrying a bounty on her head. But she was also a nurse, a Union spy and a women’s suffrage supporter. Tubman is one of the most recognized icons in American history and her legacy has inspired countless people from every race and background.

When Was Harriet Tubman Born?

Harriet Tubman was born around 1820 on a plantation in Dorchester County, Maryland. Her parents, Harriet (“Rit”) Green and Benjamin Ross, named her Araminta Ross and called her “Minty.”

Rit worked as a cook in the plantation’s “big house,” and Benjamin was a timber worker. Araminta later changed her first name to Harriet in honor of her mother.

Harriet had eight brothers and sisters, but the realities of slavery eventually forced many of them apart, despite Rit’s attempts to keep the family together. When Harriet was five years old, she was rented out as a nursemaid where she was whipped when the baby cried, leaving her with permanent emotional and physical scars.

Around age seven Harriet was rented out to a planter to set muskrat traps and was later rented out as a field hand. She later said she preferred physical plantation work to indoor domestic chores.

A Good Deed Gone Bad

Harriet’s desire for justice became apparent at age 12 when she spotted an overseer about to throw a heavy weight at a fugitive. Harriet stepped between the enslaved person and the overseer—the weight struck her head.

She later said about the incident, “The weight broke my skull … They carried me to the house all bleeding and fainting. I had no bed, no place to lie down on at all, and they laid me on the seat of the loom, and I stayed there all day and the next.”

Harriet’s good deed left her with headaches and narcolepsy the rest of her life, causing her to fall into a deep sleep at random. She also started having vivid dreams and hallucinations which she often claimed were religious visions (she was a staunch Christian). Her infirmity made her unattractive to potential slave buyers and renters.

Escape from Slavery

In 1840, Harriet’s father was set free and Harriet learned that Rit’s owner’s last will had set Rit and her children, including Harriet, free. But Rit’s new owner refused to recognize the will and kept Rit, Harriet and the rest of her children in bondage.

Around 1844, Harriet married John Tubman, a free Black man, and changed her last name from Ross to Tubman. The marriage was not good, and the knowledge that two of her brothers—Ben and Henry—were about to be sold provoked Harriet to plan an escape.

After the Underground Railroad, Harriet Tubman Led a Brazen Civil War Raid

Tubman applied intelligence she learned as an Underground Railroad conductor to lead the Combahee Ferry Raid that freed more than 700 from slavery.

6 Strategies Harriet Tubman and Others Used to Escape Along the Underground Railroad

From elaborate disguises to communicating in code to fighting back, enslaved people found multiple paths to freedom.

Harriet Tubman: 8 Facts About the Daring Abolitionist

Born into slavery, Harriet Tubman escaped to freedom in the North in 1849 and then risked her life to lead other enslaved people to freedom.

Harriet Tubman: Underground Railroad

On September 17, 1849, Harriet, Ben and Henry escaped their Maryland plantation. The brothers, however, changed their minds and went back. With the help of the Underground Railroad , Harriet persevered and traveled 90 miles north to Pennsylvania and freedom.

Tubman found work as a housekeeper in Philadelphia, but she wasn’t satisfied living free on her own—she wanted freedom for her loved ones and friends, too.

She soon returned to the south to lead her niece and her niece’s children to Philadelphia via the Underground Railroad. At one point, she tried to bring her husband John north, but he’d remarried and chose to stay in Maryland with his new wife.

Fugitive Slave Act